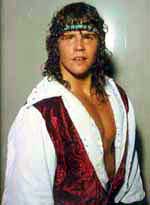

Chris Von Erich

| Chris Von Erich | |

|---|---|

| |

| Birth name | Christopher Barton Adkisson |

| Born | September 30, 1969 Dallas, Texas, U.S. |

| Died | September 12, 1991 (aged 21) Denton, Texas, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Suicide by gunshot |

| Family | Von Erich |

| Professional wrestling career | |

| Ring name(s) | Chris Von Erich |

| Billed height | 5 ft 5 in (1.65 m)[1] |

| Billed weight | 175 lb (79 kg)[1] |

| Billed from | Denton, Texas |

| Trained by | Fritz Von Erich |

| Debut | June 22, 1990[2] |

Christopher Barton Adkisson (September 30, 1969 – September 12, 1991)[3] was an American professional wrestler, best known under the ring name Chris Von Erich of the Von Erich family.

Early life

[edit]The smallest and youngest of the Von Erich family at 5'5" and 175 pounds, Chris aspired to be a wrestler.[1][4] He was the youngest son of wrestler and wrestling promoter Fritz Von Erich.[5] His brothers, Mike, David, Kerry and Kevin all had success as wrestlers. Chris was raised with his brothers on 500 acres in Texas.[6] He grew up working cameras and doing other odd jobs backstage for World Class Championship Wrestling (WCCW). He won his first amateur wrestling match at the age of six.

Professional wrestling career

[edit]Chris had minor involvement in angles in the 1980s.[5] He performed run-ins to aid his brothers against The Fabulous Freebirds.[5] Then Chris appeared at ringside when Kerry Von Erich won the NWA World Championship in May 1984. Chris also smashed Buddy Roberts across the back with a chair, and tackled Gino Hernandez at the Cotton Bowl in 1985 while he was trying to escape from having his hair shaved off following a tag-team loss at the hands of the Von Erichs.

Chris became a full-fledged wrestler in 1990.[5] He had a small feud with Percy Pringle in the United States Wrestling Association (USWA) that was seen nationally on ESPN. Chris tagged with both his brother Kevin and longtime ally Chris Adams in several tag team matches against Pringle and Steve Austin; however, he would face only Pringle whenever he was in the ring, and allow his more-experienced partner (Kevin or Adams) to battle Austin. Despite his lack of athleticism, Chris was supported by fans, who would often yell "GO, CHRIS, GO!" during his matches. In one of his early matches, Matt Borne and Pringle faced off against Kerry and Kevin Von Erich. Chris, who was at ringside, was attacked by Borne and Pringle, ramming his head into the ring apron, causing him to have a headache that lasted for five days.[7] His last known match was a victory over Todd Overbow March 31, 1991 for World Class Wrestling Association in Davis, Oklahoma.

Personal life

[edit]Chris had several health problems that limited his success as a wrestler.[5] In addition to asthma,[6][8] his bones were so brittle from taking prednisone that he would often break them while performing simple wrestling maneuvers.[5][1] After the 1987 suicide of brother Mike,[9] Chris began to experience depression and drug issues.[5] He was also frustrated by his inability to make headway as a wrestler due to his physical build.[10][11][12]

Death and legacy

[edit]On September 12, 1991, at about 9 P.M., Chris was found by his brother Kevin and mother outside of their family farm in Edom, suffering from a self-inflicted 9mm gunshot wound to the head.[13] According to Kevin, Chris came to him in the middle of the night, wanting back a videocassette recorder (VCR) Kevin borrowed from him. After noticing Chris sitting alone on top of a hill, Kevin went out and talked with him, where he revealed his suicidal tendencies concerning his condition (he had broken his arm earlier that month). After Kevin pleaded with him not to harm himself, Chris reassured him he wouldn't, but after Kevin left, he shot himself in the head.[14] He was hospitalized at the East Texas Medical Center, shortly after 10 P.M., where he died 20 minutes after arriving, at age 21.[5][15][1] Toxicology reports also revealed cocaine and Valium were in his system at the time of his death.[16] Kevin had talked to Chris earlier that day about 100–150 yards north of their home where an apparent suicide note had been left.[17] His interment was located at Grove Hill Memorial Park in Dallas.[18]

Chris's life story was combined with his brother Kerry's for the movie The Iron Claw.

Awards and accomplishments

[edit]- World Wrestling Entertainment

- WWE Hall of Fame (Class of 2009) as a member of the Von Erich family[19][20]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Wilonsky, Robert (November 20, 1997). "Wrestling With Tragedy". Dallas Observer. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ^ "World Class Memories: Results 1990 and Beyond". John Dananay/Michael Moody/ISE Web Productions. July 28, 2013. Retrieved December 9, 2013.

- ^ "Chris Von Erich". Find a Grave. Retrieved August 28, 2010.

- ^ Greenberg, Keith Elliot (January 1, 2000). Pro Wrestling: From Carnivals to Cable TV. Lerner Publications. ISBN 978-0-8225-3332-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Tragedy in Texas: The Sad Story of the Von Erich Family". Retroist. June 5, 2013. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ^ a b Hollandsworth, Skip. "The Fall of the House of Von Erich". D Magazine. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ^ Smith, Don G. Fritz Von Erich: Triumph and Tragedy. Midnight Marquee & BearManor Media.

- ^ Ahlhelm, Nicholas (December 19, 2019). "Wrestling, abuse and death: the twisted tale of the Von Erich family". Medium. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- ^ "Six Brothers". Texas Monthly. October 1, 2005. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- ^ Frater, Jamie (November 1, 2010). Listverse.com's Ultimate Book of Bizarre Lists: Fascinating Facts and Shocking Trivia on Movies, Music, Crime, Celebrities, History, and More. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-56975-885-4.

- ^ Harvey, Bill (January 1, 2010). Texas Cemeteries: The Resting Places of Famous, Infamous, and Just Plain Interesting Texans. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-77934-1.

- ^ Molinaro, John F. (2002). Top 100 Pro Wrestlers of All Time. Winding Stair Press. ISBN 978-1-55366-305-8.

- ^ Muchnick, Irv (November 16, 2010). Wrestling Babylon: Piledriving Tales of Drugs, Sex, Death, and Scandal. ECW Press. ISBN 978-1-55490-286-6.

- ^ Meltzer, Dave (2001). Tributes: Remembering Some of the World's Greatest Wrestlers. Winding Stair Press. ISBN 978-1-55366-085-9.

- ^ Cohen, Eric. "Who's who in the Von Erich Family?". Archived from the original on March 2, 2017. Retrieved April 19, 2009.

- ^ Frasier, David K. (September 11, 2015). Suicide in the Entertainment Industry: An Encyclopedia of 840 Twentieth Century Cases. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-0807-5.

- ^ "Autopsy Performed on Another Wrestling Von Erich". Greensboro News and Record. The Associated Press. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ^ Wilson, Scott (August 19, 2016). Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-2599-7.

- ^ "Von Erichs". WWE. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ^ Klein, Greg (April 18, 2014). The King of New Orleans: How the Junkyard Dog Became Professional Wrestling's First Black Superhero. ECW Press. ISBN 978-1-77090-224-4.

External links

[edit]- Chris Von Erich's profile at Cagematch.net, Internet Wrestling Database

- 1969 births

- 1991 suicides

- 1991 deaths

- 20th-century American male actors

- 20th-century male professional wrestlers

- 20th-century American professional wrestlers

- American male professional wrestlers

- People from Denton, Texas

- Professional wrestlers from Texas

- Sportspeople from Dallas

- Suicides by firearm in Texas

- Von Erich family

- WWE Hall of Fame inductees

- Sportspeople who died by suicide