Nick Bockwinkel

| Nick Bockwinkel | |

|---|---|

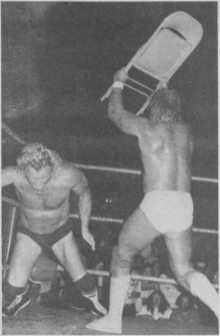

Bockwinkel in 1973 | |

| Birth name | Nicholas Warren Francis Bockwinkel |

| Born | December 6, 1934[1] St. Louis, Missouri, U.S.[1] |

| Died | November 14, 2015 (aged 80) Las Vegas, Nevada, U.S. |

| Alma mater | University of California, Los Angeles |

| Spouse(s) |

Susan Tranchitella

(m. 1957; div. 1967)Darlene Bockwinkel, née Hampp

(m. 1972) |

| Children | 2 |

| Family | Warren Bockwinkel (father) |

| Professional wrestling career | |

| Ring name(s) | Dick Warren[6][7] Nick Bock[6][8] Nick Bockwinkel[9] Nicky Bockwinkel[10] Nick Warren[11] The Phantom[11] Roy Diamond[6] |

| Billed height | 5 ft 10 in (178 cm)[9][12] |

| Billed weight | 240 lb (109 kg)[9][12] |

| Billed from | Beverly Hills, California[13][14] St. Paul, Minnesota[9][12] |

| Trained by | Warren Bockwinkel[9][15] Lou Thesz[9][15] |

| Debut | 1954[6][16] |

| Retired | May 25, 1993 |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1958–1960 |

Nick Bockwinkel | |

|---|---|

| 5th President of the Cauliflower Alley Club | |

| In office 2007–2014 | |

| Preceded by | Red Bastien |

| Succeeded by | B. Brian Blair |

Nicholas Warren Francis Bockwinkel (December 6, 1934 – November 14, 2015) was an American professional wrestler. He is best known for his appearances with the American Wrestling Association (AWA) in the 1970s and 1980s.

Bockwinkel had a lengthy professional wrestling career with matches in 34 consecutive years.[7] Debuting in 1954, Bockwinkel spent the first half of his career as a journeyman babyface, wrestling primarily in California and Hawaii with stints in Texas, Georgia, and the Pacific Northwest as well as excursions to Canada and Australia.[17][18] In 1970, he joined the Minneapolis, Minnesota-based AWA, where he would be based for the remainder of his career. Swiftly rising to prominence as a main event heel, Bockwinkel held the AWA World Tag Team Championship three times, then the AWA World Heavyweight Championship four times, before retiring in 1987.

Bockwinkel was recognized for his exceptional technical wrestling ability, mastery of in-ring psychology, and even-toned, articulate promos.[19][20][21][22] Professional wrestling historian Tim Hornbaker described him as "the definitive heavyweight champion heel of the 1970s",[23] while historian Scott Beekman described him as "the most successful heel champion in wrestling history".[24] Bockwinkel was inducted into the Wrestling Observer Newsletter Hall of Fame in 1996, the Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame and Museum in 2003, the World Wrestling Entertainment Hall of Fame in 2007, the George Tragos/Lou Thesz Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame in 2009, and the National Wrestling Alliance Hall of Fame in 2016.

Early life

[edit]Bockwinkel was born to Warren Bockwinkel – himself a professional wrestler – and Helen (née Crnkovich) Bockwinkel in St. Louis, Missouri, on December 6, 1934.[20] Bockwinkel's parents divorced when he was aged five and he lived with his grandmother until he was 12, then attended a boarding school in Indiana for two years before returning to live with his father. As Bockwinkel's father moved around the country for work, he attended four separate high schools.[10] Bockwinkel was a star fullback in high school, winning an "outstanding player" trophy in 1953.[23] He attended the University of Oklahoma on a football scholarship, playing for the Oklahoma Sooners until sustaining a pair of knee injuries that ended his football career and cost him his scholarship.[7][22][25][26] Bockwinkel subsequently transferred to the University of California, Los Angeles—studying marketing—where at the suggestion of his father he began wrestling to fund his studies.[10][16][20] After graduating from UCLA, Bockwinkel was drafted into the United States Army in 1958; he spent two years in the Army, during which time he was stationed in Fort Ord in Monterey, California.[11]

Professional wrestling career

[edit]Training

[edit]Bockwinkel was trained to wrestle by his father Warren, a regional star in the 1940s, and Lou Thesz.[9][15] He received additional training from Gene Kiniski, Lord Blears, and Wilbur Snyder.[10] When he was first breaking into professional wrestling, Bockwinkel served as the driver for Yukon Eric, taking him to various cities throughout the Eastern and Northeastern United States; he later commented that the experience, "was so smart. [...] Lots of ways to learn about this business."[23][26][27]

Early career (1954–1961)

[edit]Bockwinkel debuted in 1954 in Los Angeles, California.[7][16][23][28] He spent the early years of his career working in Southern California for the North American Wrestling Alliance, where he occasionally teamed with his father and was sometimes billed as "Nicky Bockwinkel". In 1955, he briefly held the NWA International Television Championship.[11][29][30]

From June to September 1956, during his summer break from UCLA, Bockwinkel made a foray into the Midwestern United States, performing in cities such as Chicago, Milwaukee, and St. Louis.[11][31] From July to September 1957, he had a stint in Texas, appearing with Houston Wrestling and Southwest Sports.[11][32]

In early 1958, upon being drafted into the United States Army, Bockwinkel relocated to Northern California.[11] During his military service, he moonlighted as a wrestler, appearing sporadically for NWA San Francisco and the Oakland, California-based Ad Santel Promotions under a variety of ring names.[33][34] In April 1958, Bockwinkel (wrestling under the name "Dick Warren") and Ramón Torres won the NWA World Tag Team Championship (San Francisco version). They held the titles until June 1958, when they lost to Hombre Montana and Tiny Mills. They regained the titles from Mills and Montana in July, then lost them to Gene Dubuque and Mike Valentino the following month.[35][36] In June and July 1959, Bockwinkel reappeared with the North American Wrestling Alliance. In late-1959 and early-1960, he made a handful of appearances in Indiana with NWA Indianapolis and the American Wrestling Alliance, where he was billed as "Nick Bock".[8][11][37][38]

Bockwinkel left the Army in 1960. Throughout mid-1960, he wrestled for Big Time Wrestling in Detroit. During this time, he also appeared with All Star Wrestling in Omaha, Nebraska, both as Nick Bockwinkel and under a mask as "The Phantom".[11][38] In late-1960, Bockwinkel returned to the North American Wrestling Alliance, where in December 1960 and January 1961 he won the International Television Tag Team Championship on two occasions: once with Lord Blears and once with Édouard Carpentier. His second reign lasted until May 1961, when he left California to join Southwest Sports in Texas.[39][40]

Texas and Canada (1961–1962)

[edit]In May 1961, Bockwinkel left California for Texas, where he began wrestling for Southwest Sports as an "All American babyface".[41] Shortly after debuting, he won a battle royal in the Dallas Sportatorium. His regular opponents included Angelo Poffo, Corsica Joe, Duke Keomuka, Mike DiBiase, and Waldo Von Erich. In June 1961, he unsuccessfully challenged Von Erich for the NWA Texas Heavyweight Champion. In July 1961, he unsuccessfully challenged visiting NWA World Heavyweight Champion Buddy Rogers. Bockwinkel left Texas in September 1961, wrestling a handful of matches for NWA Upstate in Buffalo, New York, before relocating to Canada.[40]

In November 1961, Bockwinkel began wrestling in Canada for the Regina, Saskatchewan-based Big Time Wrestling promotion. He occasionally teamed with George Scott, while his regular opponents included Dave Ruhl, Tiny Mills, and Killer Kowalski. In December 1961, he unsuccessfully challenged Kowalski for the NWA Canadian Heavyweight Championship. Bockwinkel left Canada in January 1962.[42]

Hawaii and California (1962–1963)

[edit]In early-1962, Bockwinkel began wrestling in Hawaii for the Honolulu-based 50th State Big Time Wrestling promotion, where he was named the inaugural NWA United States Heavyweight Champion (Hawaiian version) on arrival. He held the title until June 1962, when he lost it to King Curtis Iaukea.[43][44] During his run, he regularly teamed with Lord Blears and Neff Maiava, while his rivals included villains such as Curtis, Buddy Austin, and Tosh Togo. Bockwinkel left 50th State Big Time Wrestling in August 1962.[41][43]

Bockwinkel returned to California in September 1962, joining Roy Shire's American Wrestling Alliance, which had succeeded NWA San Francisco. He formed an "All American babyface" tag team with Wilbur Snyder, and the duo were pushed by Shire as his top babyface tag team.[41] In November 1961, Bockwinkel and Snyder won the NWA World Tag Team Championship (San Francisco version), defeating Kinji Shibuya and Mitsu Arakawa in the Cow Palace.[45] They defended the championship against teams including Dan Manoukian and Ciclón Negro and Ray Stevens and The Sheik before losing to Art Nielsen and Stan Nielsen in March 1963.[45][46] Bockwinkel left the AWA in April 1963.[46][47]

Bockwinkel returned to Hawaii in April 1963. In July 1963, he defeated King Curtis to win the NWA United States Heavyweight Championship for a second time. His reign lasted until September, when he lost to Don Manoukian in a two out of three falls match.[43] During his run, Bockwinkel teamed with Lord James Blears and briefly feuded with Dick the Bruiser.[46] Bockwinkel subsequently left Hawaii once again, relocating to the Pacific Northwest to wrestle for Pacific Northwest Wrestling.[46][47]

Pacific Northwest Wrestling (1963–1964)

[edit]In late-1963, Bockwinkel left Hawaii upon being recruited by Don Owen to join his Portland, Oregon-based Pacific Northwest Wrestling promotion.[46] He quickly began a feud with NWA Pacific Northwest Heavyweight Champion Tony Borne. In October 1963, Borne defeated Bockwinkel in a two-out-of-three falls match in which the loser was painted yellow. Later that month, Bockwinkel defeated Borne for the NWA Pacific Northwest Heavyweight Championship - his first major singles title. He lost the title to Mad Dog Vachon in November 1963.[20][48][49][50][51] In December 1963, Bockwinkel formed a tag team with Nick Kozak. In March 1964, Bockwinkel and Kozak defeated Art Michalik and The Destroyer for the NWA Pacific Northwest Tag Team Championship. Michalik and The Destroyer regained the titles in April, but Bockwinkel and Kozak won them a second time by defeating The Destroyer and Don Manoukian (substituting for Michalik, who was injured). After Kozak himself suffered an injury, Buddy Mareno replaced him as Bockwinkel's partner. Bockwinkel and Mareno held the titles until June 1964, when they lost to Pat Patterson and Tony Borne.[46][48][52] Bockwinkel left Pacific Northwest Wrestling the following month.[53]

Hawaii, California, and Australia (1964–1968)

[edit]Bockwinkel returned to Hawaii in September 1964, reforging his alliance with Lord James Blears and resuming his feud with King Curtis Iaukea.[53][54] In November 1964, Bockwinkel won the NWA Hawaii Heavyweight Championship, defeating Johnny Barend. His reign lasted until December 1964, when he lost the title to Iaukea.[55] Over the following months, his opponents included Iaukea, Harold Fujiwara, and Hard Boiled Haggerty. Bockwinkel left Hawaii in May 1965.[53][56]

In September 1965, Bockwinkel returned to the Los Angeles, California-based North American Wrestling Alliance, since renamed Worldwide Wrestling Associates (WWA). His opponents included Luke Graham, Pedro Morales, El Mongol, and Gorilla Monsoon.[53][56] Bockwinkel left WWA in January 1966, briefly returning to 50th State Big Time Wrestling in Hawaii before leaving for a tour of Australia.[57]

From March 1966 to June 1966, Bockwinkel wrestled in Australia with the World Championship Wrestling promotion. In his first appearance, he won a "Russian Roulette" battle royal in the Sydney Stadium. His regular opponents included Killer Kowalski, Pampero Firpo, Toru Tanaka, Waldo Von Erich, and Larry O'Dea.[53][58]

Following his tour of Australia, Bockwinkel returned to 50th State Big Time Wrestling in Hawaii in June 1966. In August 1966, he challenged Johnny Barend for the NWA Hawaii United States Heavyweight Championship, with the match ending in a time limit draw. He faced Barend once again in October, losing to him in a two-out-of-three falls match. In November 1966, Bockwinkel returned to Worldwide Wrestling Associates, where he wrestled until January 1967.[53][57][59]

Bockwinkel made a second tour of Australia with World Championship Wrestling from January to March 1967. In his first appearance, he participated in a one-night tournament, losing to The Beast in the semi-finals. His opponents during his second stint in Australia included Dory Funk Jr., Roy Heffernan, and Rudy LaBelle.[53][58]

Following his second tour of Australia, Bockwinkel made a handful of appearances in Hawaii before returning to Worldwide Wrestling Associates in April 1967. His regular opponents included Karl Gotch, Hard Boiled Haggerty, and Ricky Romero.[53][59] During his time in California, he appeared in an episode of the television series The Monkees.[15] Bockwinkel left WWA once more in October 1967, returning to Hawaii once more until early 1968 before moving to Texas in March 1968.[59][60]

Texas and Hawaii (1968–1969)

[edit]In March 1968, Bockwinkel began competing for the West Texas-based Western States Sports promotion, where he was cast as a babyface. Shortly after debuting, Bockwinkel formed a tag team with Ricky Romero, with the duo feuding with the Von Brauners. In April 1968, Bockwinkel and Romero defeated the Von Brauners for the Amarillo version of the NWA World Tag Team Championship. Their reign lasted until May 1968, when the Von Brauners regained the titles. Over the following months, Bockwickel continued to team with Romero as well as competing as a singles wrestler against opponents such as Gypsy Joe Rosario and Pat Patterson. In September 1968, Bockwinkel unsuccessfully challenged visiting NWA World Heavyweight Champion Gene Kiniski in two two-out-of-three falls matches. Bockwinkel left Western States Sports in October 1968.[61][62]

Bockwinkel returned to Hawaii once more in October 1968. In late-1968, he formed a tag team with Bobby Shane.[62] In December 1968, he held the NWA Hawaii Heavyweight Championship for a second time.[55] In March 1969, Bockwinkel and Shane defeated Ripper Collins and Luke Graham for the NWA Hawaii Tag Team Championship. Their reign ended the following month when they lost to Collins and Buddy Austin. Bockwinkel continued to compete in 50th State Big Time Wrestling until leaving in November 1969 to join Georgia Championship Wrestling.[14][63] During this stint in Hawaii, Bockwinkel was cast in an episode of the television program Hawaii Five-O.[64]

Georgia Championship Wrestling (1969–1970)

[edit]

In November 1969, Bockwinkel began wrestling for the Atlanta, Georgia-based Georgia Championship Wrestling promotion. It was at this time that Bockwinkel "found his calling" as a heel.[1][23] Having previously wrestled primarily as a babyface, Bockwinkel adopted a "cocky, uppity Beverly Hills California heel" persona in Georgia,[14] aligning himself with the villainous tag team The Assassins. In January 1970, Bockwinkel unsuccessfully challenged visiting NWA World Heavyweight Champion Dory Funk Jr.;[65] Funk later described Bockwinkel as "one of the best wrestling challengers for the belt. [...] He was very technical, and put a lot of thought into his interviews, his talk, his work in the ring, his persona."[66]

In January 1970, Bockwinkel defeated Joe Scarpa for the NWA Georgia Television Championship. He lost the title to El Mongol in March 1970, but the title was vacated after footage showing El Mongol using an illegal karate strike was aired; Bockwinkel defeated El Mongol in a rematch later that month. Bockwinkel's second reign ended in April 1970 when he was defeated by his former ally Assassin #2; after The Assassins were suspended and Assassin #2 was stripped of the title, Bockwinkel defeated Joe Scarpa in June 1970 to win the vacant title. His third and final reign ended in August 1970 when he lost to Bobby Shane.[65][67]

In April 1970, Bockwinkel defeated Assassin #2 for the NWA Georgia Heavyweight Championship. He held the title until July 1970, when he lost to Paul DeMarco. Bockwinkel regained the title from DeMarco later that month, with his second reign lasting until September 1970 when he lost to Buddy Colt.[65][68][69] Following his loss to Colt, Bockwinkel left Georgia, briefly returning to Hawaii once more before joining the Minneapolis, Minnesota-based American Wrestling Association.[65][70] Bockwinkel's appearances in Georgia were described by Jim Zordani as "[showing] the wrestling world he was more than capable of being the top heel in a promotion".[14]

American Wrestling Association (1970–1987)

[edit]Tag Team Champion reigns (1970–1975)

[edit]

In December 1970, Bockwinkel began wrestling for the Minneapolis, Minnesota-based American Wrestling Association (AWA).[70] Over the following months, he went on a lengthy undefeated streak (albeit while losing some matches by disqualification and count-out), with his regular opponents including Edouard Carpentier, Kenny Jay, and Paul Diamond. He sustained his first defeat in September 1971 when he unsuccessfully challenged AWA World Heavyweight Champion Verne Gagne.[71][72]

In August 1971, Bockwinkel began teaming with Ray Stevens.[9] The duo became "the most hated AWA grapplers of the early 1970s";[73] they ultimately wrestled over 300 matches together.[7] The tag team was formed when Bockwinkel interfered in a bout between Stevens and Red Bastien.[72] Bockwinkel and Stevens went on to feud with Bastien and The Crusher, the then-AWA World Tag Team Champions. In January 1972, Bockwinkel and Stevens defeated Bastien and The Crusher for the titles in a two out of three falls match, winning the final fall when Bockwinkel kicked Bastien in the stomach as he attempted to give Stevens an atomic drop.[72][74] They successfully defended the titles in a series of rematches with Bastien and The Crusher, as well as other challengers such as Billy Robinson and Dr. X, The Vachon Brothers, and Billy Robinson and Wahoo McDaniel.[13][75] During 1972, Bockwinkel and Stevens also competed in Championship Wrestling from Florida - where they briefly held the NWA Florida Tag Team Championship[76] - and several other promotions.[13][75] Their reign as AWA World Tag Team Champions finally ended in December 1972 when they lost to the "dream team" of Billy Robinson and Verne Gagne.[74][75][77]

In January 1973, Bockwinkel and Stevens regained the AWA World Tag Team Championship from Gagne and Robinson in a two out of three falls match.[74][78] Over the next 18 months, they defended the titles against teams such as the Texas Outlaws (Dick Murdoch and Dusty Rhodes), The Crusher and Mad Dog Vachon, and Billy Robinson and a series of partners including Don Muraco, Geoff Portz, Ken Patera, Red Bastien, and Wahoo McDaniel.[78] Magazine Pro Wrestling Illustrated named Bockwinkel and Stevens its "Tag Team of the Year" for 1973.[79] Their second reign ended in July 1974 when they lost to Billy Robinson and The Crusher in a two out of three falls match in a match with Greg Gagne as special guest referee.[74][78][80][81] Following their title loss, Bockwinkel and Stevens began feuding with Greg Gagne and his partner Jim Brunzell. Claiming that there was a "conspiracy" against them, in August 1974 Bockwinkel and Stevens introduced Bobby Heenan as their manager to protect their interests.[81][82][83]

In October 1974, Bockwinkel and Stevens regained the AWA World Tag Team Championship from Robinson and The Crusher following interference from Heenan.[74][80][81] In November 1974, Bockwinkel and Stevens participated in the International Wrestling Enterprise World Championship Series tournament in Japan, during which they defended their titles against The Great Kusatsu and Rusher Kimura.[80] On January 25, 1975, an angry fan fired a gun at Heenan in Chicago's International Amphitheatre after Heenan interfered in Bockwinkel's match; neither Heenan nor Bockwinkel were hit, but several audience members at ringside were injured.[84] Over the following months, Bockwinkel and Stevens defended their titles against challengers including the High Flyers (Gagne and Brunzell), Dusty Rhodes and Superstar Billy Graham, and Dusty Rhodes and Larry Hennig. Their third and final reign ended in August 1975 when they were defeated by The Crusher and Dick the Bruiser.[74][85] The team dissolved shortly thereafter when Stevens departed the AWA, with Bobby Duncum allying with Bockwinkel in November 1975.[86]

First reign as World Heavyweight Champion (1975–1980)

[edit]

In 1975, AWA co-founder and World Heavyweight Champion Verne Gagne proposed that he transition the title to his son, Greg Gagne. His business partner, Wally Karbo, proposed Bockwinkel as an alternative.[27] Bockwinkel went on to defeat Verne Gagne for the AWA World Heavyweight Championship on November 8, 1975, at the age of 40 in the St. Paul Civic Center in Saint Paul, Minnesota, ending Gagne's seven-year reign.[9][85][87] The match ended when Bobby Duncum interfered, enabling Bockwinkel to pin Gagne.[86]

Throughout 1976, Bockwinkel defended the AWA World Heavyweight Championship against challengers including Gagne, Larry Hennig, Pampero Firpo, Joe Blanchard, Jos LeDuc, Peter Maivia, Art Thomas, and The Crusher. Bockwinkel also teamed with Heenan and Bobby Duncum to face the High Flyers and various partners in a series of six-man tag team matches. In August 1976, Bockwinkel defended the AWA World Heavyweight Championship against André the Giant in a bout at Comiskey Park in Chicago, Illinois, that ended in a double disqualification.[86][88]

Following stints in Japan, California, and Florida, Ray Stevens returned to the AWA in late 1976. Stevens reunited with Bockwinkel and Heenan, who had by now also been joined by Blackjack Lanza (who held the AWA World Tag Team Championship with Bobby Duncum) in what was known as the "Heenan Family".[89] Stevens was often overlooked by Heenan, who would ignore or interrupt him during televised interviews on All Star Wrestling, angering Stevens. On the December 25, 1976, episode of All Star Wrestling, Heenan was presented with a "Manager of the Year" trophy by Pro Wrestling Illustrated editor Bill Apter. In his acceptance speech, Heenan thanked Bockwinkel, Duncum, and Lanza (overlooking Stevens), then insulted Stevens when he attempted to congratulate him. An incensed Stevens knocked down Heenan and Bockwinkel and shattered Heenan's trophy before being beaten down by the Heenan Family. The angle saw Stevens turn face and begin feuding with the Heenan Family.[90][91]

In 1977, Bockwinkel defended the AWA World Heavyweight Championship against Stevens as well as other challengers such as Billy Robinson , The Crusher, Ernie Ladd, Les Thornton, Pedro Morales, and Terry Funk.[92] In 1978, he faced new challengers such as John Tolos, Bob Armstrong, Mr. Wrestling II, Rocky Johnson, Tommy Rich, Rufus R. Jones, and Angelo Mosca, as well as old opponents such as Verne Gagne, Greg Gagne, Billy Robinson, The Crusher, and André the Giant. In December 1978, Bockwinkel and Blackjack Lanza toured Japan with All Japan Pro Wrestling, competing in the annual World's Strongest Tag Determination League.[93][94]

Bockwinkel began 1979 by successfully defending his title against challengers from around the world such as Dino Bravo, Jumbo Tsuruta, and Tiger Jeet Singh.[95] In March 1979, Bockwinkel faced WWWF Champion Bob Backlund in the first ever American Wrestling Association and World Wide Wrestling Federation title versus title bout, with the match ending in a double count-out.[9][12][96][97] In April 1979, Bockwinkel appeared with Mid Atlantic Championship Wrestling, defending his title against challengers such as Johnny Weaver and Paul Orndorff. Back in the AWA, Bockwinkel's challengers throughout the remainder of the year included Ricky Steamboat, Bill Dundee, Rick Martel, Bruiser Brody, Bobo Brazil, and Super Destroyer Mark II, as well as old adversaries such as Greg Gagne and The Crusher. In September 1979, Bockwinkel returned to Mid Atlantic Championship Wrestling, where he faced NWA World Television Champion Ricky Steamboat in a title versus title match that ended in a disqualification (meaning the title did not change hands). In October 1979, Bockwinkel wrestled in Japan for International Wrestling Enterprise as part of its "Dynamite Series" tour; during the tour, he faced IWA World Heavyweight Champion Rusher Kimura in a title versus title bout that ended with Bockwinkel being disqualified (meaning the title did not change hands).[95][98]

Bockwinkel began 1980 with defences against opponents such as The Crusher, Mad Dog Vachon, Kintarō Ōki, Wahoo McDaniel, and Scott Casey. His reign finally came to an end after 1,716 days when he was defeated by Verne Gagne in a bout in Comiskey Park on July 18, 1980, losing to Gagne's signature sleeper hold.[87][98][99]

Second reign as World Heavyweight Champion (1981–1982)

[edit]

Immediately following his loss to Gagne, Bockwinkel challenged World Wrestling Association World Heavyweight Champion Dick the Bruiser in what had been marketed as a title-versus-title match; the bout ended in a draw. Over the following months, Bockwinkel faced a series of the AWA's top faces. In November and December 1980, Bockwinkel once again toured Japan with All Japan Pro Wrestling; he competed in the World's Strongest Tag Determination League alongside Jim Brunzell, placing fourth.[99][100]

After returning from Japan, Bockwinkel unveiled his new finishing move, the "Oriental Sleeper". Throughout early 1981, Bockwinkel received a series of title shots against Gagne, but failed to defeat him. The feud culminated in a final bout between Bockwinkel and Gagne in the St. Paul Civic Center on May 10, 1981, which Gagne once again won using his sleeper hold. Gagne retired following the match, and the AWA World Heavyweight Championship was awarded back to Bockwinkel - the number one contender - on May 19, 1981.[87][101][100] This move infuriated AWA fans, solidifying Bockwinkel's status as one of the most despised wrestlers in the world.[23][26][91][102][103] Throughout the remainder of 1981, Bockwinkel faced fresh challengers such as Tito Santana, Pat Patterson, Baron von Raschke, and Adnan Al-Kaissie. He also defended the AWA World Heavyweight Championship in other promotions, facing opponents such as a young Bret Hart in Stampede Wrestling and Tony Atlas in Houston Wrestling.[101][104][105] In December 1981, he appeared in Bremen, Germany with the Catch Wrestling Association, defending the AWA World Heavyweight Championship against Austrian wrestler Otto Wanz in a bout that went to a time limit draw.[101]

In January 1982, Bockwinkel made another tour of Japan with All Japan Pro Wrestling as part of its "New Year Giant Series". Back in the AWA, Bockwinkel began feuding with Hulk Hogan, who Verne Gagne had signed after Hogan left the World Wrestling Federation.[106] Hogan had swiftly become the AWA's top babyface, with his popularity booming further following the release of Rocky III (in which Hogan appeared) in May 1982.[107] In March 1982, Hogan defeated Bockwinkel and Heenan in a non-title handicap match in the International Amphitheatre in Chicago, Illinois. Hogan went on to repeatedly challenge Bockwinkel for the AWA World Heavyweight Championship, with the matches generally ending in disqualifications (meaning the title did not change hands). In April 1982, Hogan defeated Bockwinkel and was declared the new champion, only for the decisions to be overturned by AWA president Stanley Blackburn due to the use of a foreign object during the match.[108][109][110]

During mid-1982, Bockwinkel made multiple defences of his title in other promotions, facing challengers such as Bret Hart, Keith Hart, Mr. Hito, and David Schultz in Stampede Wrestling, Dick Slater in Houston Wrestling, and Bruiser Brody in Southwest Championship Wrestling. His second reign came to an end on August 29, 1982, when he lost to Otto Wanz in the St. Paul Civic Center in St. Paul, Minnesota.[87][108] The loss - regarded as a major upset - reportedly came about after Wanz offered Verne Gagne $50,000 (equivalent to $158,000 in 2023) in return for a run as AWA World Heavyweight Champion,[91][107] enabling him to bill himself as a former world champion.[111]

Third reign as World Heavyweight Champion (1982–1984)

[edit]

Bockwinkel faced Otto Wanz in a series of rematches, eventually defeating him to win the AWA World Heavyweight Championship for a third time on October 9, 1982, in the International Amphitheatre in Chicago, Illinois.[87][108] Two days later, Bockwinkel appeared with the Continental Wrestling Association in the Mid-South Coliseum in Memphis, Tennessee, where he defeated Jerry Lawler to win the AWA Southern Heavyweight Championship. Bockwinkel spent the next month as a dual champion before losing the title back to Lawler in a no disqualification "title versus hair" match.[108][112] Bockwinkel closed out 1982 with successful defences of the AWA World Heavyweight Championship against challengers such as Rick Martel, Mike Graham, Tito Santana, Jim Brunzell, and Baron von Raschke.[108] On December 27, 1982, the AWA World Heavyweight Championship was held up after a match between Bockwinkel and Jerry Lawler ended in controversial circumstances; Bockwinkel defeated Lawler the following month to confirm his status as champion.[113]

Throughout 1983, Bockwinkel faced challengers such as Pat Patterson, Rick Martel, Baron von Raschke, Jerry Lawler, Wahoo McDaniel, and Brad Rheingans. In April 1983, Bockwinkel defended his title against Hulk Hogan once more at the Super Sunday supercard in the St. Paul Civic Center, which was attended by over 18,000 fans with over 4,000 more fans watching on closed-circuit television in the Roy Wilkins Auditorium, with Lord James Blears as special guest referee. Hogan won the bout (and the title) by pinfall following a leg drop, but subsequently AWA president Stanley Blackburn overturned the decision on the basis that Hogan had thrown Bockwinkel over the top rope (an illegal maneuver in the AWA), infuriating fans.[12][91][114][115][116][117] Behind the scenes, disputes between Hogan and Verne Gagne led Hogan to depart the AWA later that year to return to the WWF, where he was swiftly made WWF Champion and became a global star.[23][118][119][120] In July 1983, Bockwinkel returned to All Japan Pro Wrestling as part of its "Grand Champion Carnival III" tour, facing opponents such as Genichiro Tenryu and Jumbo Tsuruta.[121]

Bockwinkel began 1984 with defences against challengers such as Dino Bravo, Jerry Lawler, and Brad Rheingans.[122] He had a short feud with his former ally Blackjack Lanza, who left the Heenan Family after being berated by Bobby Heenan for losing to Greg Gagne; Bockwinkel also faced Lanza and his new partner Blackjack Mulligan in a series of tag team matches.[122][123] In February 1984, Bockwinkel returned to All Japan Pro Wrestling as part of its "Excite Series" tour; on February 23 in the Kuramae Kokugikan in Tokyo, Bockwinkel faced NWA International Heavyweight Champion Jumbo Tsuruta in a title versus title match with Terry Funk as the guest referee. The bout was won by Tsuruta, bringing Bockwinkel's third reign as champion to an end.[18][23][36][87][122][124] Similarly to Otto Wanz in 1982, Tsuruta's victory reportedly came about after All Japan Pro Wrestling owner Giant Baba paid Verne Gagne a "sizeable sum of money" for Tsuruta to have a short reign as AWA World Heavyweight Champion.[125]

Tag team with Mr. Saito; feud with Larry Zbyszko (1984–1986)

[edit]In spring 1984, Bockwinkel unsuccessfully attempted to regain the AWA World Heavyweight Championship from Jumbo Tsuruta in a series of bouts.[122] After Rick Martel won the title from Tsuruta in May 1984, Bockwinkel was his first challenger.[126] In July 1984, Bockwinkel formed a tag team with Mr. Saito and began a lengthy feud with The Fabulous Ones that lasted to the end of the year.[122] In September 1984, Bockwinkel's long-time manager Bobby Heenan left the AWA to join the World Wrestling Federation, ending their decade-long association.[125] In December 1984, Bockwinkel returned to All Japan Pro Wrestling, participating in that year's World's Strongest Tag Determination League with Harley Race as his partner.[122]

Bockwinkel and Saito continued to team in early 1985, facing teams such as Curt Hennig and Larry Hennig, The Road Warriors, and The High Flyers (Greg Gagne and Jim Brunzell) before separating in April 1985 when Mr. Saito left the AWA due to legal issues.[127][128] That same month, Bockwinkel reformed his tag team with Ray Stevens. In July 1985, the team was joined by Larry Zbyszko, with the trio feuding with Greg Gagne and Sgt. Slaughter. At the inaugural SuperClash supercard event on September 28, 1985, in Comiskey Park in Chicago, Illinois - which was attended by over 20,000 people - Bockwinkel competed on the undercard in a six-man tag team match, teaming with Stevens and Zbyszko in a loss to Curt Hennig, Greg Gagne, and Scott Hall. In November and December 1985, Bockwinkel once again participated in the All Japan Pro Wrestling World's Strongest Tag Determination League, teaming with Curt Hennig.[127]

On the December 3, 1985, episode of AWA on ESPN, Zbyszko faced Greg Gagne with Bockwinkel on color commentary at ringside. The match ended in a disqualification when Zbyszko struck Gagne in the midsection with a nunchaku. Following the match, Zbyszko struck Gagne in the back of the head, then hit Bockwinkel as he remonstrated with him. The angle saw the alliance between Zbyszko and Bockwinkel end, with Bockwinkel turning face for the first time since joining the AWA in 1970.[15][128][129] In January 1986, Bockwinkel challenged NWA World Heavyweight Champion Ric Flair at the Winnipeg Arena in Winnipeg, Manitoba; the bout ended in a double count out. Bockwinkel faced Zbyszko in a series of increasingly violent matches throughout early 1986, including Texas death matches and steel cage matches.[12][130]

Final reign as World Heavyweight Champion (1986–1987)

[edit]

In April 1986, Bockwinkel began challenging AWA World Heavyweight Champion Stan Hansen. At that month's WrestleRock 86 supercard event in the Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome in Minneapolis, Minnesota, Bockwinkel defeated Hansen by disqualification (meaning the title did not change hands).[130] After Hansen no-showed a scheduled title defence against Bockwinkel due to a prior touring commitment with All Japan Pro Wrestling, Verne Gagne stripped him of the title and Bockwinkel was named the new champion (by forfeiture) for a fourth and final time on June 28, 1986, at the age of 52. A disgruntled Hansen defended the title belt in Japan, then upon his return to the United States ran it over with his car and mailed the fragments to Gagne.[23][73][87][131][132]

Throughout the remainder of 1986, Bockwinkel defended the title against Larry Zbyszko and other challengers such as Boris Zhukov, Nord the Barbarian, and Scott Hall, as well as wrestling Curt Henning to a time limit draw in an hour-long bout.[130] In 1987, he faced challengers such as Leon White, The Super Ninja, Austin Idol, and Colonel DeBeers. His fourth and final reign as AWA World Heavyweight Champion ended on May 2, 1987, when he lost to Curt Hennig at SuperClash II in the Cow Palace in San Francisco, California.[23][87][133][134] The match ended in controversial fashion due to interference by Larry Zbyszko, who handed a roll of coins to Hennig to use on Bockwinkel.[135][136] Verne Gagne had reportedly originally intended to reverse the decision and return the title to Bockwinkel, but decided to keep the title on Hennig due to the strong reception to him during the match and a desire to prevent Hennig from leaving the AWA for the World Wrestling Federation.[137]

Bockwinkel wrestled his final match for the AWA on August 2, 1987, unsuccessfully challenging Curt Hennig. In August and September 1987 he made his final appearances with All Japan Pro Wrestling as part of its "Summer Action Series II" tour. On November 16, he participated in a World Wrestling Federation battle royal at the Brendan Byrne Arena in East Rutherford, New Jersey, alongside multiple other veteran wrestlers, with former NWA World Heavyweight Champion Lou Thesz prevailing. Bockwinkel subsequently retired from professional wrestling, marking the end of a career that spanned four decades.[134]

Retirement (1987–2015)

[edit]With the American Wrestling Association declining, in 1987 Bockwinkel approached the World Wrestling Federation and was hired as a road agent.[7][1] He also serving as a color commentator for occasional televised events after having been introduced at an arena show by Bobby Heenan as his replacement for the night.[12][8] In December 1987, he served as special guest referee for a bout between Randy Savage and The Honky Tonk Man.[82] He was released in 1989 due to budget cuts, after which he began working in financial services.[1]

Bockwinkel made a return to the ring for one night in December 1990, facing Masa Saito in a bout for New Japan Pro-Wrestling held in the Hamamatsu Arena in Hamamatsu, Japan.[23][138] He made a second return in May 1992, wrestling Billy Robinson to a time limit draw in an exhibition match for UWF International held in the Yokohama Arena in Yokohama, Japan.[139][140] Bockwinkel wrestled his last ever match on May 23, 1993, for World Championship Wrestling at the pay-per-view Slamboree 1993: A Legends' Reunion (which featured multiple veteran wrestlers), going to a time limit draw with former NWA World Heavyweight Champion Dory Funk Jr.[23][141]

In 1994, Bockwinkel became the on-screen commissioner of World Championship Wrestling. His run as commissioner quietly ended in the summer of 1995, although he was last mentioned as commissioner on a November 1995 edition of WCW Monday Nitro when WCW attorney Nick Lambrose stripped The Giant of the WCW World Heavyweight Championship. He was released by WCW in December 1995.[9][142]

In 2000, Bockwinkel and Yoshiaki Fujiwara served as commissioners for a short-lived "shoot-style" promotion, the Japan Pro Wrestling Association.[7]

On March 29, 2010, Bockwinkel made a guest appearance on WWE Raw, where he was one of several "legends" at ringside for a lumberjack match between Christian and Ted Dibiase.[143]

Legacy

[edit]Bockwinkel was known for his technical wrestling ability and in-ring psychology. Bob Backlund wrote in his autobiography that "Nick had a great head for the game, a wonderful sense of ring psychology, and an uncanny ability to use his intelligence and cockiness to get under the people's skin. He was a terrific representative for the AWA and was the key player in the success of the AWA for a long time." Backlund goes on to say, "He was a very intelligent, well-spoken, and cocky heel, and his in-ring skills were right up there with the very best in the business."[144] In the book 50 Greatest Professional Wrestlers of All Time: The Definitive Shoot, author Larry Matysik named Bockwinkel the 18th greatest professional wrestler, writing "he was an athlete, he could wrestle, and his psychology was second to none."[27] Professional wrestling journalist Dave Meltzer described Bockwinkel as "a first-rate worker".[145] Fellow wrestler Jim Wilson described Bockwinkel as "one of wrestling's truly smooth workers with a repertoire of moves executed fluidly, believably and without a hint of pain for his opponents."[146] Bockwinkel was reportedly considered by the National Wrestling Alliance as a candidate to be NWA World Heavyweight Champion in the late-1970s but withdrew his name from contention due to regarding the travelling schedule of the champion to be too arduous.[98] Richard Berger described Bockwinkel as "a poster boy for what was right about wrestling" who was "a technical maestro, capable of working smoothly and comfortably with most any opponent regardless of that man's style or limitations".[147]

Bockwinkel was known for his calm, charismatic, articulate promos, which distinguished him from many of his contemporaries.[19][20][21] "I used to use the four, five or six syllable words as best I could," Bockwinkel was quoted as saying in the book The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: The Heels. "If I ran across one I didn't know, I had a little dictionary. I would have this little dictionary, with 70 or 80 words, that I would always be perusing. I had it with me all the time. Automatically, some of these words just starting coming to me in my interviews because I was familiar with them."[20][66] Richard Berger described Bockwinkel as a "master orator" who spoke "candidly, clearly and intelligently".[147] In 2008, Chris Jericho based his new villainous wrestling persona on Bockwinkel. In his autobiography The Best in the World Jericho wrote, "The WWE had recently released an AWA retrospective DVD, and while watching it, I remembered how great a heel Bockwinkel was. He wore suits for all his interviews and used ten-dollar words that went over the average fans' heads, pissing them off markedly. Here was this pompous blowhard using the fancy talk and wearing the fancy suits, claiming to be the best because he was the World Champion, which was the truth."[148]

Bockwinkel was inducted into the Wrestling Observer Newsletter Hall of Fame in 1996 (as part of the inaugural class),[149] the Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame and Museum in 2003,[1] the World Wrestling Entertainment Hall of Fame in 2007,[9][26] the George Tragos/Lou Thesz Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame in 2009,[150] and the National Wrestling Alliance Hall of Fame in 2016.[151][152] In 2007, magazine Pro Wrestling Illustrated gave Bockwinkel its Stanley Weston Award (a lifetime achievement award).[153] In 2009, the Cauliflower Alley Club gave Bockwinkel its Iron Mike Mazurki Award.[154]

Professional wrestling style and persona

[edit]For the first half of his career, Bockwinkel was a classic babyface,[18] at one point being billed as "Young Nicky Bockwinkel, the old ladies' favorite".[155] In the second half of his career, he portrayed a "cocky, uppity Beverly Hills California heel"[14] and a "pompous blowhard".[148] Phil Nowick described him as "a classic cheating heel who was seemingly unbeatable no matter how big of a pounding he took".[156]

Bockwinkel used a variety of finishing moves over his career, including a piledriver[12] and the "Oriental Sleeper" (a sleeper hold).[100] His other signature moves included an armlock, leglock, and shoulderbreaker.[157]

Other television appearances

[edit]In 1967, Bockwinkel appeared in the episode "I Was a 99-Pound Weakling" of the television series The Monkees. In 1969, he appeared in the episode "Savage Sunday" of the show Hawaii Five-O.[9][12][15][64] In 1968, Bockwinkel appeared as a contestant on the NBC game show Hollywood Squares, winning a Pontiac Firebird, a deluxe kitchen set, and $1,300 (equivalent to $11,000 in 2023) in cash.[9][12]

| Title | Year | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Monkees | 1967 | Shah-Ku Strong Man #1 | Television (episode: "I Was a 99-Pound Weakling") |

| Hawaii Five-O | 1969 | Harry | Television (episode: "Savage Sunday") |

| The Wrestler | 1974 | Himself | Film |

Personal life

[edit]On June 22, 1957, Bockwinkel married Susan Tranchitella, with whom he had two daughters. The couple divorced in 1967.[2] Bockwinkel remarried in 1972 to Darlene Hampp, with the marriage lasting until his death.[5]

In November 2007, Bockwinkel underwent triple bypass heart surgery.[158]

In 2007, Bockwinkel was elected President of the Cauliflower Alley Club, a non-profit fraternal organization of professional wrestlers.[1][159] He stepped down in 2014 due to health issues, being replaced by B. Brian Blair.[160]

Death

[edit]Bockwinkel died from undisclosed causes on the evening of November 14, 2015, at the age of 80. Prior to his death he had been suffering from memory loss. He was survived by his wife Darlene, his two children from his first marriage, two grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren. His remains were cremated in Las Vegas and a memorial mass was held at St. Joseph Croatian Catholic Church in his hometown of St. Louis, Missouri, on November 21, 2015.[19][20][161]

Championships and accomplishments

[edit]- 50th State Big Time Wrestling

- American Wrestling Alliance

- American Wrestling Association

- Cauliflower Alley Club

- Iron Mike Mazurki Award (2009)[154]

- Championship Wrestling from Florida

- NWA Florida Tag Team Championship (1 time) – with Ray Stevens[76]

- Continental Wrestling Association

- George Tragos/Lou Thesz Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame

- Class of 2009[150]

- Georgia Championship Wrestling

- National Wrestling Alliance

- NWA Hall of Fame (Class of 2016)[151][152]

- North American Wrestling Alliance / Worldwide Wrestling Associates

- International Television Tag Team Championship (2 times) – with Édouard Carpentier (1 time) and Lord James Blears (1 time)[39]

- NWA International Television Championship (1 time)[30]

- NWA San Francisco

- NWA World Tag Team Championship (San Francisco version) (2 times) – with Ramón Torres (2 times)[35]

- Pacific Northwest Wrestling

- NWA Pacific Northwest Heavyweight Championship (2 times)[49]

- NWA Pacific Northwest Tag Team Championship (2 times) – with Nick Kozak (1 time) and Nick Kozak/Buddy Mareno (1 time)[a][52]

- Pro Wrestling Illustrated

- PWI Stanley Weston Award (2007)[153]

- PWI Tag Team of the Year (1973) – with Ray Stevens[79]

- Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame and Museum

- Western States Sports

- World Wrestling Entertainment

- Wrestling Observer Newsletter

- Wrestling Observer Newsletter Hall of Fame (Class of 1996)[149]

- ^ Buddy Mareno replaced Nick Kozak as Bockwinkel's partner during their second reign.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Johnson, Steven; Oliver, Greg (2010). The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: The Heels. ECW Press. pp. 68–71. ISBN 978-1-55490-284-2.

- ^ a b "California, County Marriages, 1850–1952 Transcription: Nicholas Warren Bockwinkel". Findmypast. Retrieved November 16, 2015.(subscription required)

- ^ "California Marriage Index 1949–1959". Ancestry.com.

- ^ "California Divorce Index 1966–1984". Ancestry.com.

- ^ a b "Minnesota, Marriage Index, 1958-2001". Ancestry.com. Retrieved May 25, 2017.(subscription required)

- ^ a b c d Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel". Cagematch.net. Retrieved May 30, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Grasso, John (March 6, 2014). Historical Dictionary of Wrestling. Scarecrow Press. pp. 49–50. ISBN 978-0-8108-7926-3.

- ^ a b c Verrier, Steven (2018). Gene Kiniski: Canadian Wrestling Legend. McFarland and Company. pp. 79, 198. ISBN 978-1-4766-3427-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "Nick Bockwinkel". WWE.com. WWE. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Zordani, Jim. "Regional Territories: AWA [1934 to 1955]". KayfabeMemories.com. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Zordani, Jim. "Regional Territories: AWA [1955 to 1960]". KayfabeMemories.com. Retrieved June 22, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Sullivan, Kevin; et al. (2020). WWE Encyclopedia of Sports Entertainment. DK. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-241-48805-8.

- ^ a b c Zordani, Jim. "Regional Territories: AWA [1972]". KayfabeMemories.com. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Zordani, Jim. "Regional Territories: AWA [1968 to 1970]". KayfabeMemories.com. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Multerer, Chris; Widen, Larry (2019). Job Man: My Life in Professional Wrestling. Wisconsin Historical Society Press. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-0-87020-926-0.

- ^ a b c Murphy, Dan; Young, Brian (2021). The Wrestlers' Wrestlers: The Masters of the Craft of Professional Wrestling. ECW Press. p. 364. ISBN 978-1-77305-687-6.

- ^ Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - career". Cagematch.net. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ a b c Funk, Terry; Williams, Scott E. (2006). Terry Funk: More Than Just Hardcore. Sports Publishing. pp. 46, 120. ISBN 978-1-59670-159-5.

- ^ a b c Meltzer, Dave (March 29, 2010). "All-time great Nick Bockwinkel passes away". Wrestling Observer Newsletter. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g Johnson, Steve (November 15, 2015). "Class personified: Nick Bockwinkel dies". SlamWrestling.net. Retrieved May 30, 2021.

- ^ a b Scherer, Dave (November 11, 2015). "Legendary AWA Champion Nick Bockwinkel Passes Away". PWInsider.com. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- ^ a b "WWE Hall of Famer Nick Bockwinkel passes away". WWE.com. WWE. November 15, 2015. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Hornbaker, Tim (2017). "Nick Bockwinkel". Legends of Pro Wrestling: 150 Years of Headlocks, Body Slams, and Piledrivers. Sports Publishing. p. 447. ISBN 978-1-61321-875-4.

- ^ Beekman, Scott (2006). Ringside: A History of Professional Wrestling in America. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-275-98401-4.

- ^ "Wrestling great Nick Bockwinkel dead at the age of 80". Fox Sports. November 15, 2015. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Freedman, Lew (2018). Pro Wrestling: A Comprehensive Reference Guide. ABC-CLIO. pp. 33–35. ISBN 978-1-4408-5351-7.

- ^ a b c Matysik, Larry (2013). "Nick Bockwinkel". 50 Greatest Professional Wrestlers of All Time: The Definitive Shoot. ECW Press.

- ^ Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - 1954". Cagematch.net. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ^ Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - 1955". Cagematch.net. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ a b ""Beat the Champ" / "Wrestling Jackpot" / "Beat the Champ" Television Title". Wrestling-Titles.com. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - 1956". Cagematch.net. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - 1957". Cagematch.net. Retrieved June 22, 2021.

- ^ Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - 1958". Cagematch.net. Retrieved June 22, 2021.

- ^ "Villains lose tag team match". The Fresno Bee (via WrestlingClassics.com). August 10, 1958. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

The 300-plus-pound Montana came in as a last-minute substitution for soldier Nick Warren, who is confined to Fort Ord with a dose of poison oak. [...] Ed. note -- "Nick Warren" was the name Nick Bockwinkel used -- a variation of his and his father's name -- to keep Fort Ord authorities unaware of his moonlighting mat career.

- ^ a b "National Wrestling Alliance World Tag Team Title [1950s San Francisco]". Wrestling-Titles.com. November 26, 2018. Retrieved June 22, 2021.

- ^ a b Lentz III, Harris M. (2015). Biographical Dictionary of Professional Wrestling (2 ed.). McFarland and Company. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-4766-0505-0.

- ^ Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - 1959". Cagematch.net. Retrieved June 22, 2021.

- ^ a b Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - 1960". Cagematch.net. Retrieved June 22, 2021.

- ^ a b "International Television Tag Team Title". Wrestling-Titles.com. December 10, 2019. Retrieved June 22, 2021.

- ^ a b Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - 1961". Cagematch.net. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ^ a b c Zordani, Jim. "Regional Territories: AWA [1960 to 1962]". KayfabeMemories.com. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- ^ Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - Stampede Wrestling". Cagematch.net. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ^ a b c Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - Mid-Pacific Promotions". Cagematch.net. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ^ a b "NWA United States Heavyweight Title [Hawaii]". Wrestling-Titles.com. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ a b c "World Tag Team Title [San Francisco 1960s - 1970s]". Wrestling-Titles.com. May 27, 2019. Retrieved June 22, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Zordani, Jim. "Regional Territories: AWA [1963 to 1964]". KayfabeMemories.com. Retrieved May 19, 2021.

- ^ a b Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - 1963". Cagematch.net. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ^ a b Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - Pacific Northwest Wrestling". Cagematch.net. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ a b Duncan, Royal; Will, Gary (2016). "NWA Pacific Northwest Heavyweight Title history". Solie.org. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ "Kosak, Vacon listed on Wednesday lineup". Statesman Journal (via NewspaperArchive.com). Salem, Oregon. October 22, 1963. p. 10. Retrieved June 5, 2019.

Nick Bockwinkle [sic] and Tough Tony Borne collide in it, and the loser gets painted yellow by the winner.

- ^ Hébert, Bertrand; Laprade, Pat (2005). Mad Dog: The Maurice Vachon Story. ECW Press. pp. 129–130. ISBN 978-1-77305-065-2.

- ^ a b Duncan, Royal; Will, Gary (2017). "NWA Pacific Northwest Tag Team Title history". Solie.org. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Zordani, Jim. "Regional Territories: AWA [1964 to 1968]". KayfabeMemories.com. Retrieved May 19, 2021.

- ^ Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - 1964". Cagematch.net. Retrieved June 28, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Hawaii Heavyweight Title". Wrestling-Titles.com. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ a b Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - 1965". Cagematch.net. Retrieved June 28, 2021.

- ^ a b Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - 1966". Cagematch.net. Retrieved June 28, 2021.

- ^ a b Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - World Championship Wrestling". Cagematch.net. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ^ a b c Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - 1967". Cagematch.net. Retrieved June 28, 2021.

- ^ Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - 1968". Cagematch.net. Retrieved June 28, 2021.

- ^ Zordani, Jim. "Regional Territories: AWA [1968]". KayfabeMemories.com. Retrieved May 20, 2021.

- ^ a b Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - National Wrestling Alliance - 1968". Cagematch.net. Retrieved May 20, 2021.

- ^ Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - 1969". Cagematch.net. Retrieved June 28, 2021.

- ^ a b Rhodes, Karen (2011). Booking Hawaii Five-O: An Episode Guide and Critical History of the 1968-1980 Television Detective Series. McFarland & Company. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-7864-8666-3.

- ^ a b c d Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - Georgia Championship Wrestling". Cagematch.net. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ a b Oliver, Greg (2007). The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: The Heels. ECW Press. pp. 68–9. ISBN 978-1554902842.

- ^ a b Duncan, Royal; Will, Gary (1999). "NWA Georgia Television Title history". Solie.org. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ Hoops, Brian (April 17, 2020). "Daily pro wrestling (04/17): WCW Spring Stampede 1994". Wrestling Observer Newsletter. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- ^ a b Duncan, Royal; Will, Gary (1999). "NWA Georgia Heavyweight Title history". Solie.org. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ a b Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - 1970". Cagematch.net. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - 1971". Cagematch.net. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ a b c Zordani, Jim. "Regional Territories: AWA [1970 to 1972]". KayfabeMemories.com. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ a b Solomon, Brian (2015). Pro Wrestling FAQ: All That's Left to Know About the World's Most Entertaining Spectacle. Backbeat Books. pp. 240, 293. ISBN 978-1-61713-627-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g Duncan, Royal; Will, Gary (2008). "AWA World Tag Team Title history". Solie.org. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ a b c Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - 1972". Cagematch.net. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ a b Duncan, Royal; Will, Gary (2015). "NWA Florida Tag Team Title history". Solie.org. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ Zordani, Jim. "Regional Territories: AWA [1972 to 1973]". KayfabeMemories.com. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ a b c Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - 1973". Cagematch.net. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

- ^ a b Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Tag team of the year". Cagematch.net. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ a b c Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - 1974". Cagematch.net. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

- ^ a b c Zordani, Jim. "Regional Territories: AWA [1974 to 1975]". KayfabeMemories.com. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ a b Shields, Brian (2010). Main Event: WWE in the Raging 80s. Simon & Schuster. pp. 28, 63. ISBN 978-1-4516-0467-2.

- ^ Lentz III, Harris M. (2018). Obituaries in the Performing Arts, 2017. McFarland and Company. p. 191. ISBN 978-1-4766-7032-4.

- ^ Pratt, Greg (October 16, 2017). "Column: Remembering the time a fan shot at Bobby 'The Brain' Heenan". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on April 24, 2018. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- ^ a b Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - 1975". Cagematch.net. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

- ^ a b c Zordani, Jim. "Regional Territories: AWA [1975 to 1976]". KayfabeMemories.com. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Duncan, Royal; Will, Gary (2009). "AWA World Heavyweight Title history". Solie.org. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - 1976". Cagematch.net. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- ^ Krugman, Michael (2009). Andre the Giant: A Legendary Life. Simon & Schuster. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-4391-8813-2.

..the Heenan Family, an ever-shifting stable of heels that began in the AWA with Bockwinkel, Stevens, Bobby Duncum, and Blackjack Lanza.

- ^ Zordani, Jim. "Regional Territories: AWA [1976]". KayfabeMemories.com. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Schire, George (2010). Minnesota's Golden Age of Wrestling: From Verne Gagne to the Road Warriors. Minnesota Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-87351-620-4.

- ^ Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - 1977". Cagematch.net. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- ^ Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - 1978". Cagematch.net. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- ^ Zordani, Jim. "Regional Territories: AWA [1978]". KayfabeMemories.com. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- ^ a b Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - 1979". Cagematch.net. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- ^ Hornbaker, Tim (2007). National Wrestling Alliance: The Untold Story of the Monopoly That Strangled Professional Wrestling. ECW Press. p. 350. ISBN 978-1550227413.

- ^ Backlund, Bob; Miller, Robert H. (2015). Backlund: From All-American Boy to Professional Wrestling's World Champion. Sports Publishing. p. 360. ISBN 978-1-61321-696-5.

- ^ a b c Zordani, Jim. "Regional Territories: AWA [1979 to 1980]". KayfabeMemories.com. Retrieved July 20, 2021.

- ^ a b Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - 1980". Cagematch.net. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- ^ a b c Zordani, Jim. "Regional Territories: AWA [1980 to 1981]". KayfabeMemories.com. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- ^ a b c Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - 1981". Cagematch.net. Retrieved July 14, 2021.

- ^ Slagle, Steve. "Nick Bockwinkel". Professional Wrestling Online Museum. Archived from the original on February 13, 2008. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ "Achievement Awards: Past Winners". Pro Wrestling Illustrated. London Publishing Co.: 87 March 1996. ISSN 1043-7576.

- ^ Zordani, Jim. "Regional Territories: AWA [1981 to 1982]". KayfabeMemories.com. Retrieved July 14, 2021.

- ^ Johnson, Steven; Oliver, Greg; Mooneyham, Mike (2013). The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: Heroes and Icons. ECW Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-77090-269-5.

- ^ Kaelberer, Angie Peterson (2003). Hulk Hogan: Pro Wrestler Terry Bollea. Capstone Publishers. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-7368-2140-7.

- ^ a b Zordani, Jim. "Regional Territories: AWA [1982]". KayfabeMemories.com. Retrieved July 14, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - 1982". Cagematch.net. Retrieved July 14, 2021.

- ^ Hunter, Matt (2013). Hulk Hogan. Infobase Publishing. pp. 1, 971. ISBN 978-1-4381-4647-8.

- ^ Smallman, Jim (2018). I'm Sorry, I Love You: A History of Professional Wrestling. Headline Publishing Group. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-4722-5421-4.

- ^ Greenberg, Keith Elliot (2000). Pro Wrestling: From Carnivals to Cable TV. Lerner Publications. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-8225-3332-0.

- ^ a b Duncan, Royal; Will, Gary (2009). "AWA Southern Heavyweight Title history". Solie.org. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ Lawler, Jerry (2002). It's Good to Be the King...Sometimes. Simon & Schuster. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-7434-7557-0.

- ^ Zordani, Jim. "Regional Territories: AWA [1983]". KayfabeMemories.com. Retrieved July 18, 2021.

- ^ Hornbaker, Tim (2018). Death of the Territories: Expansion, Betrayal and the War that Changed Pro Wrestling Forever. ECW Press. pp. 92–93. ISBN 978-1-77305-232-8.

- ^ Assael, Shaun; Mooneyham, Mike (2002). Sex, Lies, and Headlocks: The Real Story of Vince McMahon and the World Wrestling Federation. Crown Publishers. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-609-60690-2.

- ^ Alvarez, Bryan; Storm, Lance (2019). 100 Things WWE Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die. Triumph Books. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-64125-220-1.

- ^ Hogan, Hulk (2002). Hollywood Hulk Hogan. Simon & Schuster. pp. 89–92. ISBN 978-0-7434-7556-3.

- ^ Kluck, Ted (2009). Headlocks and Dropkicks: A Butt-Kicking Ride Through the World of Professional Wrestling. ABC-Clio. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-313-35482-3.

- ^ Shoemaker, David (2013). The Squared Circle: Life, Death, and Professional Wrestling. Penguin Group. p. 117. ISBN 978-1-101-60974-3.

- ^ Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - 1983". Cagematch.net. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - 1984". Cagematch.net. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- ^ Zordani, Jim. "Regional Territories: AWA [1983 to 1984]". KayfabeMemories.com. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ Pope, Kristian; Whebbe, Ray (2003). The Encyclopedia of Professional Wrestling: 100 Years of History, Headlines & Hitmakers. Krause Publications. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-87349-625-4.

- ^ a b Zordani, Jim. "Regional Territories: AWA [1983 to 1984]". KayfabeMemories.com. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

- ^ Laprade, Pat; Hébert, Bertrand (2013). Mad Dogs, Midgets and Screw Jobs: The Untold Story of How Montreal Shaped the World of Wrestling. ECW Press. pp. 1, 965. ISBN 978-1-77090-296-1.

- ^ a b Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - 1985". Cagematch.net. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- ^ a b Zordani, Jim. "Regional Territories: AWA [1985]". KayfabeMemories.com. Retrieved July 18, 2021.

- ^ Zbyszko, Larry (2010). Adventures in Larryland!. ECW Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-1-55490-322-1.

- ^ a b c Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - 1986". Cagematch.net. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- ^ Koch, Natalie (2016). Critical Geographies of Sport: Space, Power and Sport in Global Perspective. Taylor & Francis. p. 215. ISBN 978-1-317-40430-9.

- ^ Molinaro, John F. (2002). Top 100 Pro Wrestlers of All Time. Winding Stair Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-55366-305-8.

- ^ Meltzer, Dave (2004). Tributes II: Remembering More of the World's Greatest Professional Wrestlers. Sports Publishing. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-58261-817-3.

- ^ a b Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - 1987". Cagematch.net. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- ^ Hoops, Brian (May 4, 2008). "Nostalgia Review: AWA Super Clash II; Bockwinkel vs Hennig; Blackwell vs. Zhukov; Midnight Rockers and more". PWTorch.com. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ Hofstede, David (1999). Slammin': Wrestling's Greatest Heroes and Villains. ECW Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-55022-370-5.

- ^ Keith, Scott (2012). Dungeon of Death: Chris Benoit and the Hart Family Curse. Kensington Books. pp. 176–177. ISBN 978-0-8065-3562-3.

- ^ Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - New Japan Pro Wrestling - 1990". Cagematch.net. Retrieved July 6, 2021.

- ^ Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - Union of Professional Wrestling Force International - 1992". Cagematch.net. Retrieved July 6, 2021.

- ^ Shannon, Jake; Robinson, Billy (2012). Physical Chess: My Life in Catch-As-Catch-Can Wrestling. ECW Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-77090-215-2.

I did an exhibition match with Nick Bockwinkel. I was in no shape to do it, and neither was Nick, but we went over and did it on one of the big UWFi fight cards.

- ^ Hoops, Brian (May 26, 2008). "Nostalgia Review: WCW Slamboree 1993; Vader vs. Davey Boy Smith; Hollywood Blonds vs. Dos Hombres; Nick Bockwinkel vs. Dory Funk Jr". Pro Wrestling Torch. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ McAvennie, Michael (2021). Austin 3:16: 316 Facts & Stories about Stone Cold Steve Austin. ECW Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-77305-723-1.

- ^ Keller, Wade (March 29, 2010). "WWE Raw Results 3/29: Keller's live ongoing coverage of WrestleMania 26 fallout, Shawn Michaels's retirement and farewell". Pro Wrestling Torch. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ Backlund, Bob; Miller, Robert H. (2013). The All-American Kid: Lessons and Stories on Life from Wrestling Legend Bob Backlund. Skyhorse Publishing.

- ^ Meltzer, Dave (1988). The Wrestling Observer's Who's who in Pro Wrestling. Wrestling Observer.

- ^ Wilson, Jim; Johnson, Weldon T. (2003). Chokehold: Pro Wrestling's Real Mayhem Outside the Ring. Xlibris. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-4628-1172-4.

- ^ a b Berger, Richard (2009). A Fool for Old School... Wrestling, That is. Lulu.com. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-9812498-0-3.

- ^ a b Jericho, Chris; Fornatale, Peter Thomas (2014). The Best In The World: At What I Have No Idea. Gotham. p. 34.

- ^ a b "Wrestling Observer Newsletter Hall of Fame". Wrestling-Titles.com. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ a b Johnson, Mike (June 30, 2009). "Ricky Steamboat, Nick Bockinkel among 2009 class honored by Wrestling Museum & Institute". PWInsider. Retrieved November 30, 2018.

- ^ a b Scherer, Dave (April 8, 2016). "NWA announces 2016 Hall of Fame class". Pro Wrestling Insider. Retrieved April 8, 2016.

- ^ a b "National Wrestling Alliance Hall of Fame". Wrestling-Titles.com. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ a b Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Stanley Weston Award". Cagematch.net. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ a b Oliver, Greg (April 16, 2009). "Top CAC award goes to top CAC man Nick Bockwinkel". SlamWrestling.net. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- ^ Zordani, Jim. "Regional Territories: AWA [1956]". KayfabeMemories.com. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ Nowick, Phil (2011). Wrestling with Life: Stories of My Life Immersed in the Sport of Wrestling. AuthorHouse. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-4567-5818-9.

- ^ Napolitano, George (1987). Wrestling: The Greatest Stars. Random House. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-517-64466-9.

- ^ Durham, Andy (November 12, 2007). "Booker T puts the "T" back in TNA, Nick Bockwinkel hits a triple". Greensboro Sports. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ Napolitano, George (2011). Hot Shots and High Spots: George Napolitano's Amazing Pictorial History of Wrestling's Greatest Stars. ECW Press. p. 302. ISBN 978-1-77090-064-6.

- ^ Johnson, Steve (November 15, 2015). "Different kind of 'Killer Bees' at Cauliflower Alley". SlamWrestling.net. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ Fletcher, Harry (November 15, 2015). "WWE Hall of Famer and former AWA World Heavyweight Champion Nick Bockwinkel dies aged 80". Digital Spy. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ "NWA Hawaii Tag Team Title". Wrestling-Titles.com. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ "The Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame and Museum". Wrestling-Titles.com. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ "World Tag Team Title [W. Texas]". Wrestling-Titles.com. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

External links

[edit]- Nick Bockwinkel on WWE.com

- Nick Bockwinkel's profile at Cagematch.net , Wrestlingdata.com , Internet Wrestling Database

- Nick Bockwinkel at IMDb

- 1934 births

- 2015 deaths

- 20th-century male professional wrestlers

- 20th-century American professional wrestlers

- American expatriate professional wrestlers in Japan

- American color commentators

- American male professional wrestlers

- American people of Croatian descent

- AWA World Heavyweight Champions

- AWA World Tag Team Champions

- Contestants on American game shows

- NWA "Beat the Champ" Television Champions

- NWA Florida Tag Team Champions

- NWA Georgia Heavyweight Champions

- NWA National Television Champions

- Oklahoma Sooners football players

- People from St. Louis

- Professional wrestlers from Missouri

- Professional wrestling announcers

- Professional wrestling authority figures

- Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame and Museum

- Stampede Wrestling alumni

- Heenan Family members

- United States Army soldiers

- University of California, Los Angeles alumni

- WWE Hall of Fame inductees

- NWA World Tag Team Champions (Texas version)