Ye Choirs of New Jerusalem

| "Ye Choirs of New Jerusalem" | |

|---|---|

| Easter hymn | |

| Text | by Robert Campbell |

| Language | English |

| Based on | "Chorus novae Ierusalem" by Fulbert of Chartres |

| Meter | Common metre |

| Melody | "St. Fulbert" |

| Published | 1850 |

"Ye Choirs of New Jerusalem" or "Sing, Choirs of New Jerusalem" is an English Easter hymn by Robert Campbell. It is a 19th-century translation of the medieval Chorus novae Ierusalem, attributed to Fulbert of Chartres. The text's primary focus is the Resurrection of Jesus, taking the theme of Jesus as triumphant victor over death and deliverer of the prisoners from Hell.

The text was first published by Robert Campbell in 1850, and partially rewritten by the compilers of the first edition of Hymns Ancient and Modern. The hymn remains popular in modern compilations, notably appearing in the Carols for Choirs collection. It is normally paired with the tune "St. Fulbert" by Henry John Gauntlett. It has also been set to music as an anthem by Charles Villiers Stanford, and this version is equally in common use in Anglican churches.

History

[edit]The hymn first appears in multiple 11th-century manuscripts, so if the attribution to St. Fulbert (who died c. 1029) is correct, "it must have become popular very quickly".[1] The hymn was widely used on the British Isles. In the Sarum Breviary, it is listed for the Vespers of the Easter Octave and for all Sundays from then until the Feast of the Ascension. It also appears in the York, Hereford and Aberdeen breviaries,[2][3] and remains present in late medieval manuscripts.[4]

The modern text first appeared in Campbell's Hymns and Anthems for Use in the Holy Services of the Church within the United Diocese of St Andrews, Dunkeld, and Dunblane (Edinburgh, 1850).[5] The editors of Hymns Ancient and Modern altered Campbell's text in various places, replaced the final stanza with a doxology, and added "Alleluia! Amen" to the hymn's end.[6] Other translations of the hymn by J. M. Neale, R. F. Littledale, R. S. Singleton and others were also in common use at the end of the 19th century.[2]

Further changes to Campbell's setting include alterations to the fifth stanza, sometimes omitted entirely, due to its references to "soldiers" and "palace".[7]

Text

[edit]The original Latin hymn is written in iambic dimeter, with lines of 8 syllables each in quatrains with an a-a-b-b rhyme scheme.[8][9] The most common version nowadays is based on the translation of Robert Campbell, which is in the shorter common metre. The version by John Mason Neale is in the original long metre and thus unsingable to the same modern tune as Campbell’s. Neale’s version better reflects the original and shows that Campbell's version, as retouched in Hymns Ancient and Modern and later hymnals, is a "Victorian creation".[7]

The first stanza begins with an invitation to sing. It refers to the "New Jerusalem" of Revelation 21:2 and uses "Paschal victory" instead of the more frequent "paschal victim" (victimae paschali).[10] The second stanza describes Jesus as the Lion of Judah of the Old Testament and the fulfillment of the promise of Genesis 3:15,[6] although the medieval text more probably had the idea of the harrowing of Hell in mind, an idea also present in stanza three. The fourth and fifth stanza incite the believer to worship the triumphant Christ. The final stanza was added by the editors of Hymns Ancient and Modern[2] and is a doxology, a common metre setting of the Gloria Patri.[10]

| Original Latin text[11] | Translation by J. M. Neale[12] | Translation by Robert Campbell[13] |

|---|---|---|

Chorus novae Ierusalem |

Ye Choirs of New Jerusalem! |

Ye choirs of new Jerusalem, |

Musical settings

[edit]"Ye Choirs of New Jerusalem" has been described as the "only medieval resurrection hymn still widely sung", but it owes more of its enduring popularity to the vigour of Campbell's translation and to the hymn's cheerful tune than the original text.[7] The original chant melody, in the 3rd mode,[4][14] is not associated with the modern text, although it appears as a setting for Neale's translation in the 1906 English Hymnal,[15] and for one of Neale's other texts in the 1916 Hymnal of the American Episcopal Church.[16]

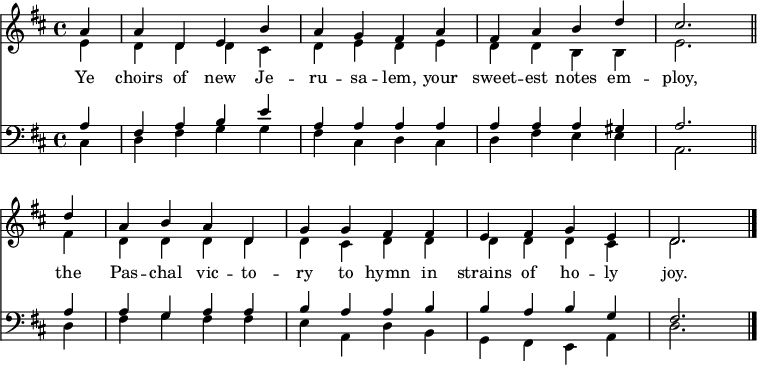

The hymn is most commonly set to[17] and was made famous by[18] the tune "St Fulbert" by Henry John Gauntlett, which first appeared in The Church Hymn and Tune Book (London, 1852). There it was used for the hymn "Now Christ, our Passover, is slain" and was known as "St Leofred". The editors of Hymns Ancient and Modern set Campbell's altered text to it and renamed it according to the original Latin author, adding a concluding "Alleluia! Amen".[6] A setting appears in the 1987 collection 100 Carols for Choirs, with the harmonisation from the English Hymnal (transcribed below)[13] and a last verse descant by David Willcocks.[19] An alternative tune is "Lyngham", a fuguing tune by Englishman Thomas Jarman,[17] whose "astonishing and invigorating" choral-style polyphony echoes the first stanza instruction for "choirs" to employ their "sweetest notes".[10]

Settings as an anthem

[edit]A notable setting of the hymn to music is in the form of an anthem for Eastertide by Charles Villiers Stanford. Completed in December 1910 and published as the composer's Op. 123 by Stainer & Bell the next year, this setting of all six stanzas of the hymn uses completely new musical material,[18] with two main musical ideas, the first in major mode in triple metre ('Ye choirs of New Jerusalem') and the second in minor quadruple metre ('Devouring depths of hell their prey'). The piece begins in G major and modulates through various keys, alternating between the two main themes before concluding in a fanfare-like fashion on "Alleluia! Amen".[20]

Other settings in the form of an anthem include works by Ivor R. Davies, Archie Fairbairn Barnes and Hugh Blair.[21][22][23] The hymn has also been set, to a new melody, by contemporary composer Kile Smith.[24]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Milfull, Inge B. (1996). The Hymns of the Anglo-Saxon Church: A Study and Edition of the 'Durham Hymnal'. Cambridge University Press. p. 452. ISBN 978-0-521-46252-5.

- ^ a b c Arderne Shoults, William (1892). "Chorus novae Hierusalem". In Julian, John (ed.). A Dictionary of Hymnology (1957 ed.). New York: Dover Publications.

- ^ Moorsom, Robert Maude (1903). A Historical Companion to Hymns Ancient and Modern. CUP Archive.

- ^ a b "Chorus novae Jerusalem novam". Cantus Manuscript Database. cantus.uwaterloo.ca. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ For a reproduction of the text as it appears in the poet's manuscript, see Shipley, Orby (1884). Annus Sanctus: Hymns of the Church for the Ecclesiastical Year. Burns and Oates. p. 142.

- ^ a b c Day, Nigel (1997). "Ye choirs of New Jerusalem". Claves Regni. St Peter's Church, Nottingham. Archived from the original on 31 August 2009. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ a b c Adey, Lionel (2011). Hymns and the Christian Myth. UBC Press. pp. 65–66. ISBN 978-0-7748-4490-1.

- ^ "Chorus novae Ierusalem". The Canterbury Dictionary of Hymnology. Canterbury Press. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ This is equivalent to modern long metre

- ^ a b c Munson, P.; Drake, J. F. "Sing, Choirs of New Jerusalem | Congregational Singing". www.congsing.org.

- ^ "Chorus novae Ierusalem". gregorien.info. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ Neale, J.M. (1867). "Chorus Novae Jerusalem". Mediæval Hymns and Sequences. pp. 48–49.

- ^ a b "754. Ye choirs of new Jerusalem". hymnary.org. Complete Anglican Hymns Old and New. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ "Chorus novae Jerusalem". Global Chant Database. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ "Hymn 122. Ye choirs of new Jerusalem". The English Hymnal. 1906. p. 166.

- ^ "The Hymnal: as authorized and approved by the General Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America in the year of our Lord 1916 page 788". hymnary.org.

- ^ a b "Sing, Choirs of New Jerusalem". Hymnary.org. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ^ a b Dibble, Jeremy (1998). "Ye choirs of New Jerusalem, Op 123 (Stanford)". www.hyperion-records.co.uk. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ^ Willcocks, David; Rutter, John, eds. (1987). 100 Carols for Choirs. Oxford University Press. pp. 380–381. ISBN 978-0-19-353227-4.

- ^ "January 2018". St Michael and All Angels Church, Mount Dinham, Exeter. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ Campbell, R.; Davies, Ivor R. (March 1935). "Ye Choirs of New Jerusalem". The Musical Times. 76 (1105): 241. doi:10.2307/919238. JSTOR 919238.

- ^ Campbell, R.; Barnes, Fairbairn (February 1938). "Extra Supplement: Ye Choirs of New Jerusalem". The Musical Times. 79 (1140): 24. doi:10.2307/923228. JSTOR 923228.

- ^ St. Fulbert of Chartres; Campbell, R.; Blair, Hugh (1 February 1925). "Ye Choirs of New Jerusalem. Anthem for Eastertide". The Musical Times. 66 (984): 145. doi:10.2307/913531. JSTOR 913531.

- ^ "Sing, Choirs of New Jerusalem". Kile Smith, composer. 20 April 2019. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

External links

[edit]- Ye choirs of new Jerusalem (Charles Villiers Stanford): Free scores at the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Ye Choirs of New Jerusalem on YouTube in Stanford's setting, sung by the Choir of New College, Oxford

- Ye choirs of new Jerusalem on YouTube (arr. Willcocks) sung by the Choir of King's College, Cambridge with the Philip Jones Brass Ensemble