Chinese Buddhist canon

The Chinese Buddhist canon refers to a traditional collection of Chinese language Buddhist texts which are the central canonical works of East Asian Buddhism.[1][2][3] The traditional term for the canon is Great Storage of Scriptures (traditional Chinese: 大藏經; simplified Chinese: 大藏经; pinyin: Dàzàngjīng; Japanese: 大蔵経; rōmaji: Daizōkyō; Korean: 대장경; romaja: Daejanggyeong; Vietnamese: Đại tạng kinh).[3] The Chinese canon is a major source of scriptural and spiritual authority for East Asian Buddhism (the Buddhism of China, Korea, Japan and Vietnam). It is also an object of worship and devotion for Asian Buddhists and its reproduction is seen as an act of merit making.[4][5] The canon has also been called by other names like “Internal Classics” (neidian 内典), “Myriad of Scriptures” (zhongjing 眾經), or “All Scriptures” (yiqieing 一切經).[6]

The development of the Great Storage of Scriptures was influenced by the Indian Buddhist concept of a Tripitaka, literally meaning "three baskets" (of Sutra, Vinaya, and Abhidharma), a term which referred to the scriptural canons of the various Indian Buddhist schools. However, Chinese Buddhists historically did not have access to a single Tripitaka from one school or collection.[7] Instead, the canon grew over centuries as various Indian texts were translated and new texts composed in China. These various works (4,878 individual texts according to the Chinese scholar He Mei) were later collected into a distinct Chinese canon.[8][9]

The Chinese Buddhist Canon also contains many texts which were composed outside of the Indian subcontinent, including numerous texts composed in China, such as philosophical treatises, commentaries, histories, philological works, catalogs, biographies, geographies, travelogues, genealogies of famous monks, encyclopedias and dictionaries. As such, the Great Storage of Scriptures, the foundation of East Asian Buddhist teachings, reflects the evolution of Chinese Buddhism over time, and the religious and scholarly efforts of generations of translators, scholars and monastics.[10][9] This process began with the first translations in the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) after which a period of intense translation work followed in the succeeding dynasties. The first complete canons appear in the Eastern Jin and the Sui Dynasties, while the first woodblock printed canon (xylography), known as the Kaibao Canon, was printed during the Song dynasty between 971 to 983.[11] Later eras saw further editions of the canon published in China, Korea and Japan like the Tripitaka Koreana (11th & 13th centuries) and the Qianlong Canon (1735-1738). One of the most widespread edition used by modern scholars today is the Taishō Tripiṭaka, produced in Japan in the 20th century. More recent developments have seen the establishment of digital canons available online, such as CBETA online (Chinese Buddhist Electronic Text Association).

The language of these scriptures is termed "Buddhist Chinese" (Fojiao Hanyu 佛教漢語), and is a variety of literary Chinese with several unique elements such as a distinctly Buddhist terminology that includes transliterations from Indian languages and newly coined Chinese Buddhist words.[12][13]

History

[edit]Early period

[edit]In India, the early Buddhist teachings were collected into canons called tripiṭaka (‘three baskets’; Chin. 三藏 sānzàng ‘three stores’ or ‘three repositories’). Most canons contained sūtras (discourses of the Buddha, 經 jīng), monastic rule texts (vinaya; 律 lǜ); and scholastic treatises (abhidharma; 阿毘曇 āpítán or 阿毗達磨 āpídámó). Initially these sources were transmitted orally but later they were written down into various manuscript collections.[14] Each of the Indian Buddhist schools had their own canon, which could differ significantly from that of other schools and be in different languages (prakrits like Gandhari and Pali, as well as classic Sanskrit and Hybrid Sanskrit). Some schools had extra pitakas or divisions, including a Dharani Pitaka, or Bodhisattva Pitakas.[14][15]

According to Guangchang Fang, the history of the Chinese Buddhist Canon can be divided into four main periods: the handwriting era (from the Han up to the 10th century) which was also the era of intense translation effort, the era of woodblock printing (beginning in the Song dynasty with the Kaibao edition of the 10th century), the era of modern printing, and the digital era.[16][17]

The first Chinese translations of Buddhist texts appeared during the later Han Dynasty during the reign of Emperor Ming (r. 58–75 ce). The first sutra to be translated is said to be the Sutra of Forty-two Sections (四十二章經 sìshíèr zhāng jīng).[14] Many of the early translators were monks from Central Asia, like the Parthian Ān Shìgāo (安世高), and the Kuchan translator Kumārajīva (鳩摩羅什; 343– 413).[18] Later figures were native Chinese who traveled to India and studied Sanskrit texts there, like Fǎxiǎn (法顯, c. 337–422 ce) and Xuánzàng (玄奘, 602–664 ce). Most translators who produced significant translations did not work alone, making use of teams of translators and scribes. Thus, the texts of the Chinese canon were translated by various figures from different source texts (in different forms of Sanskrit and prakrit). This process happened over several centuries and thus the various texts of the Chinese canon reflect different translation styles and philosophies.[18] According to a Yuan dynasty catalogue (the Zhiyuan fabao kantong zonglu 至元法寶堪同總錄), there were about 194 known translators who worked on about 1,440 texts in 5,580 fascicles (juans).[4][19] Jiang Wu writes that "for about a thousand years, translating, cataloging, and digesting these texts became a paramount task for Chinese Buddhists."[20]

From the Han to the Song dynasty era, many translations were made and made new texts were also composed in China.[16] During the Eastern Jin and the Sui Dynasties, the earliest canons were compiled using manuscripts.[4][16] None of these early manuscript canons have survived.[4] The earliest surviving manuscripts from the early Chinese canons are found in the Dunhuang text collections and the earliest catalogue of the contents of the canon is the Lidai sanbao ji 歷代三寳記 (Records of the Dharma Jewels through the Generations) by Fei Changfang (fl. 562–598).[17] There are also many early manuscripts which have survived in the libraries of Japanese temples.[17]

Another surviving early collection of Chinese Buddhist canonical material is the Fangshan Stone Sutras (房山石經) which a set of around 15,000 stone tablets containing Buddhist sutras carved at Yúnjū Temple (雲居寺).[21][4] This project was begun in the 7th century by a devout monk named Jìngwǎn. His followers at the temple continue to carve sutras on stone tablets for generations after (even well into the Ming dynasty). The earliest dated Heart Sutra from 661 comes from this collection of stone carved sutras.[22][23]

Alongside the study, translation and copying of these numerous texts, Chinese Buddhists spent much time organizing, classifying and cataloguing them. In this effort, Chinese Buddhists were also influenced by the work of Confucian cataloging, especially the work of Liu Xiang (77–6 BCE).[24]

A key milestone in the organization of the canon was the compilation of the Kaiyuan Catalogue (Kāiyuán Shìjiàolù, 開元釋教錄, Kaiyuan Era Record of Buddhist Teachings, Taishō Tripitaka No. 2154) during the Tang dynasty by the monk Zhisheng (699-740).[16] This catalogue provided the main blueprint for the restoration and organization of future canons after the Great Buddhist Persecution in 845.[25][17] The Kaiyuan catalogue is also considered by modern scholars as a text which "closed" or fixed the core portion of the canon. As such, according to Jiang Wu "for centuries, despite the fact that the canon has continued to grow, this core body has remained stable, without much alteration."[26] This Kaiyuan set of core texts became the defining feature of the Chinese Buddhist canon. Any collection that did not include these was not considered a complete canon. However, many monasteries or temples who could not afford to maintain a full set would keep a “Small Canon” (xiaozang 小藏), which consisted of the essential Mahayana scriptures found within the canon. These are the Mahayana sutras contained in the first four sections of the canon: Prajñaparamita, Ratnakuta, Avatamsaka and Nirvana sections).[27]

The print era

[edit]

The developments of the early manuscript canons influenced the compilation of the first printed canon (the Kaibao Canon) during the Song dynasty. The Kaibao was completed in 983 and comprised 130,000 woodblocks, organized according to the Kaiyuan catalogue.[25][17] Printing technology brought about a revolution in how the canon was reproduced, as well as in its layout, style and the various social elements associated with its production.[28]

After the Song, the manuscript canons gradually disappeared and were replaced by printed canons. However, the practice of hand copying sutras remained an important religious practice, some figures famously copied sutras by hand in their own blood. Sutra copying was also retained as an elite art form that made use of ink mixed with gold and silver powder and produced richly decorated manuscripts.[17] This shift from manuscript culture to xylography introduced several changes to the physical layout and other material aspects of the new printed canons.[4] One of these changes was the use of the Thousand Character Classic for a library classification system. Each text was assigned a character from this classic work which was widely memorized by school children and thus known by all educated persons.[4]

Regarding physical aspects, while the Kaibao canon came in scrolls made from several sheets of paper pasted together, later editions were packaged in different styles such as accordion folding books and the string binding style initiated by the Jiaxing canon (also called "Indian style" since it imitated Indian manuscripts).[4] Texts were also preceded or closed by prefaces and colophons that contained information such as titles, text origin, printing date, sponsors, and even the names of printers and binders.[4] Some editions also included illustrations of various scenes, such as Buddha assemblies from specific sutras and landscapes.[4] Various types of paper were used for the canons, many of them being made from mulberry and hemp, while woodblocks were made from pear wood or jujube wood.[4]

After printing, a canon would usually be stored monasteries and temples. Many monasteries in imperial China also had specific buildings where their copies of the canon were stories, which were called Tripitaka Pavilions (zangjingge 藏經閣) or Tripitaka Tower (jingge 经阁 or jinglou 經樓).[29] Temples also had special cabinets produced for storing canonical texts. These huge cabinets were called "tripitaka cabinets" and were of different designs. Some were built into the walls of a library, others were revolving repositories (lunzang 輪藏) that could be turned to easily access different texts.[4] These revolving storage structures were also devotional items, as it was often believed that turning these repositories could bring good merit.[30]

In the following one thousand years of Chinese Buddhist history, fifteen further editions of the Chinese Buddhist canon were constructed. Half of these were royal editions, supported by the Imperial Court, while other canons were made through the efforts of laypersons and monastics.[25]

Producing and worshiping the canon

[edit]

Throughout its history, the Chinese Buddhist canon was also an object of worship and devotion for whole Buddhist communities. It represented the ultimate teaching of the Buddha and the Buddha's body.[5] This practice has its roots in the Indian worship of Mahayana sutras. Some scholars even speak of a "cult of the canon" when referring to the various devotional activities which revolved around the creation, distribution, and preservation of the Chinese Buddhist canon.[4][5] These activities included sponsoring the printing of a canon, working on the project, ceremonial rituals consecrating the texts, reading and manual ritual copying of the texts (a practice which remained important even as printing dominated the production of sutras).[4]

Many Chinese elites, including the imperial family and also even common people all aspired to support the copying and distribution of the Buddhist canon.[5] Printing and owning a full set of the canon was considered to enhance the prestige of a temple or monastery, while sponsoring the production of the canon was considered to have protective and apotropaic powers which could extent to the nation.[5] Thus, one of the reasons for the copying of the Korean canon was the belief that the merit produced by this act could protect the nation from foreign invasion.[5] Likewise, the emperors of the Tang dynasty believed that sponsoring the production of Buddhist canons would have numerous benefits, including protecting the nation, bringing peace, bring good merit to the imperial family, and make the nation's subjects more moral and less rebellious.[31] Monks, literati and even commoners also supported the copying and printing of the canon to a lesser extent, sometimes doing the copying themselves as a devotional practice or providing funds for a single page or a single block to be carved.[32]

The production and printing of the Chinese canon often relied on extensive administrative offices which supervised the project. Editions sponsored by the state were often produced by a specific government printing agency. During the Ming, this was called the scripture factory (jingchang 經廠) and it was run by eunuchs. Furthermore, at the local level, various administrative agencies also oversaw the transfer of an imperial canon to a Buddhist monastery. In the Ming, this process was handled by the Ministry of Rites.[33] The process relied on numerous types of staff, including "the sponsors, supporters, chief fund raisers, assistant fund raisers, chief monks to manage the canon, chief monks to manage the print blocks, collators and proofreaders, carvers, and printing workers."[33] There were also many private individuals which were involved, including private printing shops, monastic printers, merchants, and local literati.[33]

Aside from copying and reading, another textual practice which was popular in Asia was the ceremony called "sunning the scriptures" (shaijing 曬經), which developed out of the need to regularly take out texts to prevent dampness. This utilitarian practice developed into a ritual in which the texts would be displayed to the public who would come to venerate them.[4]

Another popular ritual was the ceremonial reading of the entire canon, a rite called "turning the scriptures" (zhuanjing 轉經). This was also sometimes done by a person as a solitary spiritual practice.[4] Ritually reading the whole canon was said to bring much merit, and it was also sometimes used as a funerary practice.[34] Yet another common practice was the circumambulation around the canon stored in a Tripitaka Hall which was accompanied by chanting.[35]

Language

[edit]The texts of the Chinese Buddhist canon are written in a unique variant of written Chinese which is termed Buddhist Chinese by scholars.[36] This language is the main religious and liturgical language of East Asian Buddhism. It was the main language of Buddhist scholasticism and liturgy not just in China, but in Korea, Japan and Vietnam for all of their pre-modern history.[37] Scholars also distinguish between two main categories of Buddhist Chinese: the language of Chinese translations of Indian texts and the language of indigenous Chinese compositions.[37]

"Buddhist Chinese" contains several features that distinguish it from standard literary Chinese. One of these is the fact that Buddhist Chinese makes greater of disyllabic and polysyllabic words. Much of this is due to Buddhist terminology not found in other literary Chinese works. Some of these are transliterations from Indian languages such as Sanskrit, for example 波羅蜜 (pinyin: bōluómì) for the Sanskrit term pāramitā and 佛陀 (Middle Chinese pronunciation: *butda, modern pronunciation: fotuo).[38][37] Buddhist Chinese also includes many calques or loanword translations. Examples include 如來 (pinyin: rúlái, "thus come") which refers to the term Tathagata, and fangbian 方便 (lit. “method and convenience”, a term for upāya).[38][37]

Buddhist Chinese texts also contain unique syntax which is not used in non-Buddhist literary Chinese. One example is the use of vocatives in the middle of a sentence, which is not allowed in grammar of classical Chinese but is found in Sanskrit.[37] For example, in his Vimalakirti Sutra translation, the translator Zhi Qian sometimes follows the Sanskrit word order: 時 我 世尊 聞 是 法 默 而 止 不 能 加 報 (At that moment, I, Oh Lord, heard this law, [was] silent and stopped [speaking]; Skt. aham bhagavan etām śrutvā tūṣṇīm eva abhūvam).[37] This matching of the word order of the Sanskrit source texts is common in Chinese Buddhist translations.[37]

Another feature of Buddhist Chinese is that many Buddhist Chinese texts tend to rely on more vernacular elements than non-Buddhist literary Chinese.[39][37]

However, these generalizations should be understood to be very broad since, as Lock and Linebarger write:

it should be borne in mind that the term in fact covers the language of thousands of texts, both those translated from Sanskrit and other languages, and those written originally in Chinese. The texts are also in a large number of different genres, and were produced over a period of nearly two thousand years. This vast corpus includes texts in a kind of ‘translationese’, influenced by the vocabulary and grammar of the original languages from which they were translated, texts written throughout in an elegant Wenyan style, and texts containing a lot of colloquial language, some of which is recognizably MSC [Modern Standard Chinese]. So any generalizations made about BC will not hold for every text.[38]

As such, the earliest translations like Zhi Qian and Dharmarakṣa are different in many ways to those of Kumarajiva and also to those of Xuanzang and his followers, who had different translation philosophies and ways of translating key terms and phrases.[37] And all of these works are significantly different than the vernacular Chinese compositions found in genres like “sutra lectures” (jiang jingwen 講經文), baihua shi 白話詩 “vernacular poems” and the Chan yulu 語錄 “recorded sayings” literature.[37]

Editions and contents

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

The various editions of the Chinese Buddhist canon all include translations of Indian Āgama, Vinaya and Abhidharma texts from the Early Buddhist schools, as well as translations of the Mahāyāna sūtras, śāstras (treatises) and scriptures from Indian Esoteric Buddhism. The various canons also contain texts composed in China, Korea and Japan, including apocryphal sutras and Chinese Buddhist treatises.[4] These additional non-Indic works include philosophical treatises, commentaries, philological works, catalogues, sectarian writings, geographic works, travelogues, biographies, genealogies and hagiographies, encyclopedias and dictionaries.[4] Furthermore, each edition of the canon has its own organizational schema, with different divisions for the various types of texts.

The development of the Buddhist canons also saw the development of other supplemental texts, including textual catalogues and lexicographical works. Catalogues contained much information about the texts in the canon, including how it was translated, its content and its textual history and authenticity (whether a text which claims to be Indian was actually Indian or not).[4] Dictionaries were also important supplements to the various canons, explaining difficult terms and names found in the various texts of the canon. One influential example was Huilin's Sounds and Meanings of the Canon (c. 810), which explains the meanings of 6,000 characters.[4]

The earliest manuscript canon may have been compiled as early as the later fifth or early sixth century.[40] While the Kaibao Canon is the earliest printed canon (completed c. 983), it is the Zhaocheng Jin Tripitaka, which dates to the Jin dynasty (1115–1234), that is the earliest Tripitaka collection that survives intact.[41] While more than twenty different woodblock canons were carved in China throughout the history of Chinese Buddhism, the Goryeo Tripitaka and the Qianlong Tripitaka are the only collections which have survived as complete woodblock printing sets. All other woodblock canons were fully or partially lost and destroyed in wars.[17]

Regarding the printed canons, they are all part of three “text families” or “lineages” of canons which borrow from previous editions in content, format, organization and carving style. According to Chikusa Masaaki and Fang Guangchang, all printed canons can be grouped into three main textual systems: "the tradition of central China based on Kaibao Canon, the northern tradition based on Khitan Canon, and the southern tradition based on Chongning Canon".[42]

Kaibao canon

[edit]The first printed version of the Chinese Buddhist canon was Song dynasty Kaibao Canon (開寶藏) also known as the Shu-pen (蜀本) or Sichuan edition (since it was printed in Sichuan province). It was printed on the order of Emperor Taizu of Song (r. 960–976) and the work of printing the whole canon lasted from 971 to 983.[43] [11] This canon comprised 5,048 fascicles and 1,076 titles, only 14 fascicles from this canon survive today.[44]

The blocks used to print the Kaibao Canon were lost in the fall of the Northern Song capital Kaifeng in 1127 and there are only about twelve fascicles worth of surviving material. However, the Kaibao formed the basis for future printed versions that do survive intact. Most importantly, the Kaibao (along with later editions like the Liao dynasty edition) was the main source for the Tripitaka Koreana, which in turn was the basis for the modern Taisho edition.[11] It was also the main source for the Zhaocheng Canon. As such, the Kaibao has been one of the most influential canons in Chinese history.[42]

Liao Khitan Canon

[edit]The Liao Canon 遼藏 or Khitan Canon 契丹藏 was printed in the Liao Dynasty (916–1125) during the reign of Emperor Shengzong (983–1031), shortly after the printing of the Kaibao Canon. It followed a different manuscript tradition than the Kaibao.[44] It had 1,414 titles and 6,054 fascicles.[44]

Chongning Canon and the Southern canons

[edit]After the Song government lost their war with the Jin dynasty and moved to the south in 1127, Buddhists in southern China worked to make new editions of the canon. This resulted in the Chongning Canon produced in Fuzhou and completed in 1112. This canon was based on a different manuscript canon than the one that had been used to carve the Kaibao Canon. The Chongning Canon became the basis for later canons like the Song era Pilu Canon 毗盧藏, the Sixi Canon 思溪藏 (including the Yuanjue Canon and Zifu Canon) and the Qisha Canon as well as the Yuan era Puning Canon 普寧藏 and the Japanese Tokugawa period Tenkai Canon 天海藏.[45] The Qisha canon was particularly unique because it was produced not by the state but by private funding and effort, continuing the southern tradition of printed canons.[45]

Korean canon

[edit]

The earliest edition of the Korean canon or Tripiṭaka Koreana (Koryŏ Taejanggyōng 高麗大藏經), also known as the Palman Daejanggyeong (80,000 Tripitaka), was first carved in the 11th century during the Goryeo period (918–1392). The first edition was completely destroyed by the Mongols in 1232 and thus a second set was carved from 1236 to 1251 during the reign of Gojong (1192–1259).[10]

This second Korean canon was carved into 81,258 woodblocks. According to Lewis R. Lancaster "each was carved on both sides with twenty-three lines of fourteen characters each. The calligraphy was excellent and the layout such that all the characters appeared in large size. The blocks measured two feet three inches in length and nearly ten inches in width and more than an inch in thickness. A very hard and durable wood from the Betula schmidtii regal tree (known as Paktal in Korean), gathered on the islands off the coast, was used."[10]

These woodblocks were kept in good condition until the modern era, and are seen as accurate sources for the classic Chinese Buddhist Canon. Today, the woodblocks are stored at the Haeinsa temple, in South Korea.[46]

The main texts in this canon are divided into main sections: a Mahāyāna Tripiṭaka and a Hīnayāna Tripiṭaka, each one having the three classic sub-divisions of Sūtra, Vinaya, and Abhidharma.[47] There are also supplementary sections with texts of East Asian provenance.[47][4]

The contents of the Korean Canon (which follows the organization of Zhisheng's Kaiyuan Catalogue) are as follows:[47][4]

- 大乘三藏 Mahāyāna Tripiṭaka

- 大乘經 Mahāyāna Sūtra

- 般若部 Prajñāpāramitā (1–21)

- 寶積部 Ratnakūṭa (22–55)

- 大集部 Mahāsannipāta (56–78)

- 華嚴部 Avataṃsaka (79–104)

- 涅槃部 Parinirvāṇa (105–110)

- 五大部外諸重譯經 Other Major Sūtras (111–387)

- 單譯經 Minor Sūtras (388–522)

- 大乘律 Mahāyāna Vinaya (523–548)

- 大乘論 Mahāyāna Abhidharma

- 釋經論 Sūtra Commentaries (549–569)

- 集義論 Collected Treatises (570–646)

- 大乘經 Mahāyāna Sūtra

- 小乘三藏 Hīnayāna Tripiṭaka

- 小乘經 Hīnayāna Sūtra

- 阿含部 Āgama (647–800)

- 單譯經 Minor Sūtras (801–888)

- 小乘律 Hīnayāna Vinaya (889–942)

- 小乘論 Hīnayāna Abhidharma (943–978)

- 小乘經 Hīnayāna Sūtra

- 賢聖傳記錄 Records of the Noble Ones

- 西土賢聖集 Sages of the West (979–1046)

- 此土撰述 Writings of This Land (1047–1087)

- 宋續入藏經 Song Period and Later Additions (1088–1498)

Zhaocheng Jin Canon

[edit]

The Jin Dynasty Zhaocheng Canon 趙城藏 (also known as the Jin Canon 金藏) was based on the Kaibao Canon.[44]

The blocks were carved between 1149 and 1178, a project led by the nun Cui Fazhen 崔法珍. This canon contains 1,576 titles in 6,980 fascicles. The woodblocks were originally stored at Hongfa Monastery in Beijing. This canon was supplemented various times during the Yuan dynasty.[44] Copies of this canon were also distributed in Shanxi under the auspices of Kublai Khan (1215–1294).[48]

One of these copies of the Jin Canon (containing about 4,800 fascicles) was re-discovered in 1933 at Guangsheng Temple, Zhaocheng County, Shanxi (hence the name Zhaocheng canon).[44] This canon was used as the basis for the modern Chinese Tripitaka compiled and published in the 1980s.[44]

Japanese canons

[edit]

The Buddhist canon, known as the Issaikyō (一切經, lit. "the entirety of the scriptures") in Japanese, also played an important role in the history of Japanese Buddhism. The canon was first chanted in 651 at a royal palace and in 673, Emperor Tenmu ordered the Issaikyō to be copied in full. During the Nara period (710-794), the imperial government led a large-scale copying of the Issaikyō at Tōdaiji. At least twenty nine manuscript canons were copied during the Nara period and many manuscripts from this period have survived.[49] In the following eras, the canon was widely copied and maintained at various temple libraries and repositories, often with support from the government or important nobles. Some early important libraries included the collection at Nanatsudera 七寺 (in Nagoya) and the library at Bonshakuji.[50]

These collections were often used for rituals in which the sutras were recited, an act which was seen as bringing merit and protecting the state. This practice was called tendoku (転読) and is discussed by Nihon shoki 日本書紀, an important 8th century history book.[50] A full manuscript set of the Issaikyō copied between 1175 and 1180 survives in Nanatsu-dera temple. It has been declared a National Treasure of Japan and an Important Cultural Property.[51] Modern scholars have discovered that several manuscripts in this canon were based on old Nara era manuscripts which preserve pre-Song dynasty readings.[51]

The practice of copying Buddhist scriptures led to a new class of scribes, the standardization of textual production as well as the rise of manuscript art. Some copies of the canon were lavishly decorated, like the Jingo-ji Tripiṭaka, commissioned by Emperor Toba and Emperor Go-Shirakawa from 1150-1185. This canon was written in golden ink on 5400 scrolls of Indigo dyed paper.

Block-printing in large scale arrived relatively late to Japan. It was only during the Edo Period, in the 17th Century that the Japanese produced a printed canon, the Tenkai Edition (天海版) which was completed in 1648 and was based on a Yuan Dynasty edition. Its production was sponsored by Tokugawa Iemitsu (1623–51) and led by the influential monk Tenkai (1534–1643).[44] Before this time, Japanese Buddhists relied on hand copied texts or printed copies imported from the mainland.[44]

A later edition, known as the Ōbaku Canon 黃檗藏 (or Tetsugen Canon 鐵眼藏 ), was begun in 1667 by a monk of the Ōbaku school named Tetsugen who set up a print shop in Kyoto.[44] The Ōbaku Canon, a reprint of the Chinese Jiaxing Canon, was the most important edition of the canon in Japan until the modern creation of the Taisho canon.

Yongle northern canon

[edit]

The Yongle Northern Tripiṭaka (yongle beizang 永樂北藏), named after the Yongle Emperor, was the most important canon carved in the Ming dynasty (1368 to 1644). It was carved in the new capital of Beijing from 1419 to 1440.[47] This canon was very similar to a previous Ming era Yongle canon, called the Yongle Southern Canon (Yongle nanzang 永樂南藏, c. 1413 to 1420).[44]

The Yongle canons were the first canons to merge all the texts into a single set of pitakas.[44] Previous canons like the Korean canon had followed the older schema of having two main divisions of "Hīnayāna" and Mahāyāna sections (each with separate sub-divisions for the Sūtra, Vinaya, and Abhidharma texts of each yana). The Yongle canons however merged all these texts into a single collection of Sūtra, Vinaya, and Abhidharma (which sub-divisions for Mahāyāna and Hīnayāna).[47]

As such, the structure of the Yongle Northern canon was as follows:[4]

- Sūtra Piṭaka

- Hīnayāna Sūtra

- Mahāyāna Sūtra

- Hīnayāna and Mahāyāna Sūtras added to the canon during the Song and Yuan dynasties

- Vinaya Piṭaka

- Hīnayāna Vinaya

- Mahāyāna Vinaya

- Abhidharma Piṭaka

- Hīnayāna Abhidharma

- Mahāyāna Abhidharma

- Hīnayāna and Mahāyāna Abhidharma texts added to the canon during the Song and Yuan dynasties

- Miscellaneous works

- Works of the Sages and Wise men of the Western Country (India)

- Works of this country (China)

- Chinese works added to the canon in the Ming dynasty

This canon was also influential outside of China, as it was re-printed in Japan under the auspices of Tetsugen Doko (1630–1682), a renowned master of the Ōbaku school.[52]

The Yongle canons became the basis for later canons, including the Jiaxing Canon (Jiaxing zang 嘉興藏 or Jingshan zang 徑山藏) of the late Ming and early Qing as well as the later Qing Canon (Qing zang).[53] This canon was also influential outside of China, as it was re-printed in Japan under the auspices of Tetsugen Doko (1630–1682), a renowned master of the Ōbaku school.[52]

Qianlong canon

[edit]The Qianlong Dazangjing (乾隆大藏經) also known as the Longzang (龍藏 “Dragon Store”) or the "Qing Canon" (清藏) was produced in Qing Dynasty (1644–1912) between the 13th year of Yongzheng (1735 CE) and the third year of the reign of the Qianlong Emperor (1738 CE). The edition of the Buddhist canon, based on the Yongle, contains 1,675 titles in 7,240 fascicles and survives in a complete set of woodblocks (79,036 blocks). It is the last canon printed in the traditional style (without any punctuation or modern typography) and the best preserved of the classic Chinese Tripitakas in China.[44][54][47]

Taishō canon

[edit]

The Taishō Tripiṭaka (taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新脩大藏經) is one of the most influential modern editions, being widely used by modern scholars. Led by Junjiro Takakusu, Kaigyoku Watanabe, and Ono Genmyo, over 300 Japanese scholars worked on compiling the Taishō from 1922–1934 and a total number of 450,000 people worked on the project.[55][56][17] The project cost 2.8 million Japanese yen.

Named after the Taishō era of Japanese history, a modern standardized edition was published in Tokyo between 1924 and 1934 in 100 volumes. It is one of the first editions of the canon with modern punctuation and also scholarly notes.[57][17]

The main section of the Taishō (the section that contains the traditional contents of the Chinese Buddhist Canon) has fifty-five volumes and 2,184 texts. The main section of the Taishō mostly consists of copies of the second edition of the Korean (Koryŏ) canon. These texts were checked and collated with various other canons, such as those housed at Zōjō-ji temple (which houses the Sixi Canon made in the Song, and the Puning Canon from the Yuan), with the Ming era Jiaxing Canon and with the Chongning Canon and Pilu Canon stored at the Library of the Imperial Household (Kunai-shō).[17] The Japanese scholars also referenced the Pali canon and Sanskrit manuscripts.[17] Some texts which were missing from the Koryŏ canon were also added from other sources such as Japanese collections or other Chinese canons.[58][17]

The Taishō editors also compiled catalogues, an index, and a glossary.[17] The Taishō scholars also provided scholarly annotations that contain alternate readings from other sources, though it was not a true critical edition of the Chinese canon. It also contained punctuation marks not found in the earlier canons, though they are often mistaken.[58]

The Taishō canon was also revolutionary in the way it organized the canonical texts. It abandoned the traditional canonical schemas of organization which date back to the Kaiyuan catalogue.[4] Instead, the Taisho was organized into the following categories based on the historical development of Buddhist texts:[55][4]

- Āgamas (equivalent to the contents of the Pali Sutta Piṭaka, vols 1-2)

- Biographies of Buddha and his disciples, Jātakas (vols 3-4).

- Mahāyāna Sūtras, grouped into the six sections (627 texts in thirteen vols.):

- Prajñaparamita (vols 5-8).

- Lotus Sūtra (vol. 9)

- Avatamsaka (vols 9-10)

- Ratnakūta (vol. 11)

- Mahāparinirvāna (vol. 12)

- Mahā-sannipāta (vol. 13)

- General ‘Sūtras’ (mostly Mahāyāna) (vol. 14-17)

- Esoteric Texts Section (572 texts, vols 18-21).

- Vinayas (monastic rules) and some texts outlining Mahayana bodhisattvas ethics (eighty-six texts in three vols. 22-24).

- Indian commentaries on the Āgamas and Mahāyāna Sūtras (thirty-one texts in three vols. 24-26).

- Abhidharma (non-Mahayana Abhidharma) texts (twenty-eight scholastic Buddhist texts in four vols. 26-29).

- Mādhyamaka (vol. 30)

- Yogācāra (vol. 31)

- Collected Treatises (vol. 32)

- Chinese Sutra commentaries (twelve vols. 33-39).

- Chinese Vinaya commentaries (vol. 40)

- Chinese commentaries on treatises (vols 40-44)

The Supplementary section of the canon contains further texts including:[4]

- Schools and Lineages section (vols 44-48)

- History and Biography section (vols 49-52)

- Sourcebook section, with dictionaries etc (vols 53-54)

- Non-Buddhist Teachings section (Hindu, Manichaean, and Nestorian Christian works) (vol 54)

- Catalogues section (vol 55)

Furthermore there are more sections for supplementary content by Japanese authors (30 volumes), supplementary sections of extra sutra, vinaya and sastra commentaries, a supplementary section on schools and lineages, a supplementary section for liturgical texts in Siddham script, a section for Dunhuang texts, a section for lost ancient texts, suspected texts and twelve volumes of iconographical content.[4]

Zhonghua Dazangjing

[edit]The Zhonghua Dazangjing (中華大藏經), also called the Tripitaka Sinica, is a modern edition of the Chinese canon developed by Chinese scholars. The project was led Professor Ren Jiyu 任繼愈 (1916–2009) between 1984 and 1996 and sponsored by the Chinese state.[17][44] This edition was based on the Zhaocheng jinzang canon (趙城金藏), and made use of eight other editions like the Korean Tripitaka for proofreading and adding sections missing from the Zhaocheng copies.[17] [59]

The original goal of the project was to include many texts not included in many of the traditional canons, such as texts preserved in Fangshan Stone Canon and the supplementary sections of other canons like the Jiaxing, Pinjia, Puhui, and the Taisho.[59] In 1994, the main section of the canon was completed, including 1,937 titles in 10,230 fascicles.[59]

The planned supplementary sections were later undertaken by other projects. The Chinese Manuscripts in the Tripitaka Sinica (中華大藏經–漢文部份 Zhonghua Dazangjing: Hanwen bufen), a new collection of canonical texts, was published by Zhonghua Book Company in Beijing in 1983–97, with 107 volumes of literature, are photocopies of early manuscripts,[60][61] and include many newly unearthed scriptures from Dunhuang.[62] There are also newer Tripitaka Sinica projects.[63]

Electronic editions

[edit]

The Taishō Tripiṭaka became the basis for electronic editions of the Chinese Buddhist canon. The two main projects currently available online for free are the SAT Daizōkyō Text Database and the Chinese Buddhist Electronic Text Association (CBETA).[4][64] There is also a project in South Korea to digitize the Tripitaka Koreana.[64] The digitization of these canons became possible with the expansion of Unicode Character encoding standard to include many ancient Chinese characters. These digital editions also contain the ability to conduct a search of the entire database.

The digital editions of the canon have also seen further improvements of the texts from previous printed editions. For example, when the Taisho Canon was first printed, many old characters found in the Tripitaka Koreana (the main source of the Taisho) were not available to the original Taisho Canon typesetters, who thus had to choose alternative Chinese characters. The new electronic editions of the Taisho have allowed for easier restoration of the original characters as Unicode expanded its base of Chinese characters.

Supplemental material

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Chinese Buddhism |

|---|

|

Numerous collections of supplemental texts which are not found in the main traditional canonical editions have been published by modern scholars as part of modern collections of the canon or as supplemental volumes. Perhaps the most well known are the supplemental volumes to the Taishō Canon which include Japanese Buddhist works, Dunhuang texts, illustrations and so forth.[55]

The use of old catalogues is an important supplement to the study of the Chinese Buddhist canon, its history and lost editions. [65] The most famous and influential catalog that is included in the Taishō is the Kaiyuan Shijiao Lu 開元釋教錄 (Taisho no. 2154). Other catalogs are included in Volume 55.

The Xuzangjing (卍續藏) version, which is a supplement of another version of the canon, is often used as a supplement for Buddhist texts not collected in the Taishō Tripiṭaka. The Jiaxing Tripitaka is another supplement for Ming dynasty and Qing dynasty Buddhist texts,[66] and as well as the Dazangjing Bu Bian (大藏經補編) published in 1986.[67]

Dunhuang texts

[edit]The manuscript finds at Dunhuang contain numerous Buddhist texts in Chinese and in other languages like Tibetan and Old Uyghur which are either not in the main Chinese canon or are significantly different versions. Most these texts are no later than the 11th century, the date of the closing of the largest trove of texts found in the so-called Library Cave (Cave 17).[68] These finds have been influential on modern East Asian Buddhist scholarship and are an important supplement to the study of East Asian Buddhist texts found in the main canonical collections. The Dunhuang texts have been published by different modern scholarly projects.[69]

Non-collected works

[edit]A number of apocryphal sutras and texts composed in China are excluded from the main collections of the canon. These Chinese works include sutras like High King Avalokiteshvara Sutra and other texts, some of which are important to Chinese folk religions.[70][71][72][73][74] Some of these works can be found in supplementary volumes to the different editions of the canon.

Translations

[edit]

In the medieval period, several translations of Chinese Buddhist texts were made into other languages by various groups within the Chinese Buddhist sphere of influence. In the modern era, the contents of the Chinese canon were also translated into modern languages like Korean, Japanese and English.

Uyghur Buddhist texts

[edit]From the 11th to the 14th centuries, Uyghur Buddhism thrived especially in Qocho, Beshbaliq and Ganzhou regions. Uyghur Buddhists made many translations into Old Uyghur. Many of these texts have survived.[75]

Tangut Tripitaka

[edit]The Mi Tripitaka (蕃大藏經) is a full Buddhist canon translated into the Tangut language from Chinese sources.[76] This canon was the main source for the Buddhism of the Tangut people of the Western Xia dynasty (1038–1227). Today, this canon is studied by a small group of scholars who work in the field of Tangutology. Eric Grinstead published a collection of Tangut Buddhist texts under the title The Tangut Tripitaka in 1971 in New Delhi.

Manchu Canon

[edit]The Qianlong Emperor (1711–1799) had the Chinese Buddhist canon translated into the Manchu language during his reign.[77] This Qing dynasty translation of the canon is known as the Manchu Canon (ch. Qingwen fanyi dazangjing 清文繙譯大藏經, mnc. Manju gisun i ubiliyambuga amba kanjur nomun). The project involved more than 90 scholars working for 20 years.[77] The sutras were translated from the Qianlong edition of the Chinese canon but the Vinaya texts were actually translated from the Tibetan canon.[77]

Modern translations

[edit]The Goryeo canon has been translated in full into modern Korean. The Taisho canon was also translated in full into modern Japanese during the 20th century under the auspices of Takakusu Junjiro and other Japanese Buddhist scholars. Many sutras and treatises have been translated into English by various scholars, but many works remain untranslated into English. In 1965, Bukkyo Dendo Kyokai (Society for the Promotion of Buddhism, BDK) was founded by Dr Yehan Numata with the express goal of translating the entire canon into English.[78]

Samples

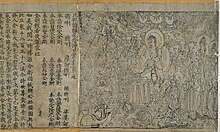

[edit]-

Song dynasty Chinese printed sutra page

-

Tripiṭaka Koreana printed sutra page

See also

[edit]- Early Buddhist texts

- Pali Canon

- Pali literature

- Sanskrit Buddhist literature

- Gandhāran Buddhist Texts

- Taisho Tripitaka

- Tripitaka Koreana

- Tibetan Buddhist canon

- Zhaocheng Jin Tripitaka

- Taoism

- Confucianism

- Jingo-ji Tripiṭaka

Citations

[edit]- ^ Han, Yongun; Yi, Yeongjae; Gwon, Sangro (2017). Tracts on the Modern Reformation of Korean Buddhism. Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism (published September 20, 2017).

- ^ Storch, Tanya (2014). The History of Chinese Buddhist Bibliography: Censorship and Transformation. Cambria Press (published March 25, 2014).

- ^ a b Jiang Wu, "The Chinese Buddhist Canon" in The Wiley Blackwell Companion to East and Inner Asian Buddhism, p. 299, Wiley-Blackwell (2014).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Wu, Jiang (2014), "The Chinese Buddhist Canon", The Wiley Blackwell Companion to East and Inner Asian Buddhism, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 361–382, doi:10.1002/9781118610398.ch18, ISBN 978-1-118-61039-8, retrieved November 27, 2024

- ^ a b c d e f Jiang & Chia (2016), p. 3.

- ^ Jiang & Chia (2016), pp. 18-19.

- ^ Jiang Wu, "The Chinese Buddhist Canon through the Ages: Essential Categories and Critical Issues in the Study of a Textual Tradition" in Spreading Buddha's word in East Asia: the formation and transformation of the Chinese Buddhist canon, p. 23, ed. Jiang Wu and Lucille Chia, New York: Columbia University Press (2015)

- ^ Lancaster, Lewis, "The Movement of Buddhist Texts from India to China and the Construction of the Chinese Buddhist Canon", pp. 226-227, in Buddhism Across Boundaries--Chinese Buddhism and the Western Regions, ed. John R McRae and Jan Nattier, Sino-Platonic Papers 222, Philadelphia, PA: Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, University of Pennsylvania (2012)

- ^ a b Jiang & Chia (2016), p. 19.

- ^ a b c Lancaster, Lewis. "The Korean Buddhist Canon: A Descriptive Catalogue". www.acmuller.net. Retrieved November 26, 2024.

- ^ a b c Lancaster, Lewis R.; Park, Sung Bae. The Korean Buddhist Canon: A Descriptive Catalogue, p. x. University of California Press, Jan 1, 1979.

- ^ Lock, Graham; Linebarger, Gary S. Chinese Buddhist Texts: An Introductory Reader, Introduction. 2018

- ^ Mair, Victor H.(梅维恒) 1994. Buddhism and the Rise of the Written Vernacular in East Asia: The Making of National Languages. The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 53, No. 3: 707–751. 汉译:佛教与东亚白话文的兴起:国语的产生(王继红、顾满林译), 载Zhu, Qingzhi(朱庆之)编Fojiao Hanyu yanjiu 佛教汉语研究 [Studies of Buddhist Chinese]. Beijing: Shangwu yinshuguan 北京:商务印书馆 [Beijing: The Commercial Press]. 2009: 358–409.

- ^ a b c Lock, Graham; Linebarger, Gary S. Chinese Buddhist Texts: An Introductory Reader, p. 1. 2018

- ^ Baruah, Bibhuti. Buddhist Sects and Sectarianism. 2008. p. 52

- ^ a b c d Long, Darui; Chen, Jinhua. Chinese Buddhist Canons in the Age of Printing, Introduction. Routledge, May 21, 2020

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Guangchang Fang (2016) Chinese Buddhist canon: approaches to its compilation, Studies in Chinese Religions, 2:2, 89-106, DOI: 10.1080/23729988.2016.1199154

- ^ a b Lock, Graham; Linebarger, Gary S. Chinese Buddhist Texts: An Introductory Reader, p. 2. 2018

- ^ Jiang & Chia (2016), p. 17.

- ^ Jiang & Chia (2016), p. 17.

- ^ 房山石经的拓印与出版 Archived 2010-12-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lancaster, Lewis R. (1989). 'The Rock Cut Canon in China: Findings at Fang-shan,' in The Buddhist Heritage, edited by Tadeusz Skorupski [Buddhica Britannica 1]. 143-156. Tring: The Institute for Buddhist Studies.

- ^ Li Jung-hsi (1979). 'The Stone Scriptures of Fang-shan.' The Eastern Buddhist. Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 104-113

- ^ Jiang & Chia (2016), p. 18.

- ^ a b c Lock, Graham; Linebarger, Gary S. Chinese Buddhist Texts: An Introductory Reader, p. 3. 2018

- ^ Jiang & Chia (2016), p. 36.

- ^ Jiang & Chia (2016), p. 37.

- ^ Jiang & Chia (2016), p. 38.

- ^ Jiang & Chia (2016), pp. 50-52

- ^ Jiang & Chia (2016), p. 56.

- ^ Jiang & Chia (2016), p. 48.

- ^ Jiang & Chia (2016), pp. 58-59.

- ^ a b c Jiang & Chia (2016), p. 9.

- ^ Jiang & Chia (2016), p. 60

- ^ Jiang & Chia (2016), p. 68.

- ^ Lock, Graham; Linebarger, Gary S. Chinese Buddhist Texts: An Introductory Reader, p. 6. 2018

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Zhu, Qingzhi; Li, Bohan (August 10, 2018). "The language of Chinese Buddhism: From the perspective of Chinese historical linguistics". International Journal of Chinese Linguistics. 5 (1): 1–32. doi:10.1075/ijchl.17010.zhu. ISSN 2213-8706.

- ^ a b c Lock, Graham; Linebarger, Gary S. Chinese Buddhist Texts: An Introductory Reader, pp. 7-9. 2018

- ^ Lock, Graham; Linebarger, Gary S. Chinese Buddhist Texts: An Introductory Reader, p. 9. 2018

- ^ Jiang & Chia (2016), p. 20.

- ^ Li, Fuhua [李富华] (May 19, 2014). 《赵城金藏》研究 [Studies of the "Zhaocheng Jin Tripitaka"]. 弘善佛教网 www.liaotuo.org (in Chinese). Retrieved May 15, 2019.

Currently the Beijing Library has 4813 scrolls...regional libraries have a total of 44 scrolls...555 scrolls belonging to the Jin Tripitaka were discovered in Tibet's Sakya Monastery in 1959--[in total approximately 5412 scrolls of the Jin Tripitaka (which if complete would have had approximately 7000 scrolls) have survived into the current era. The earliest dated scroll was printed in 1139; its wood block was carved ca. 1139 or a few years before.]

[permanent dead link] - ^ a b Jiang & Chia (2016), p. 22.

- ^ Wu, Jiang; Chia, Lucille; Chen, Zhichao (2016). "The Birth if the First Printed Canon". In Wu, Jiang; Chia, Lucille (eds.). Spreading Buddha's Word in East Asia: The Formation and Transformation of the Chinese Buddhist Canon. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 164–167.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Fuhua, Li, He Mei, and Jiang Wu, 'Appendix 1: A Brief Survey of the Printed Editions of the Chinese Buddhist Canon', in Jiang Wu, and Lucille Chia (eds), Spreading Buddha's Word in East Asia: The Formation and Transformation of the Chinese Buddhist Canon (New York, NY, 2015; online edn, Columbia Scholarship Online, 19 May 2016), https://doi.org/10.7312/columbia/9780231171601.005.0002[dead link] accessed 28 Nov. 2024.

- ^ a b Jiang & Chia (2016), p. 23.

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Haeinsa Temple Janggyeong Panjeon, the Depositories for the Tripitaka Koreana Woodblocks" (PDF). whc.unesco.org.. The Ming Jiaxing Tripitaka (嘉興藏) and the Qing Qianlong Tripitaka (乾隆藏) are still completely extant in printed form.

- ^ a b c d e f "Chinese Buddhist Canons - Lapis Lazuli Texts". lapislazulitexts.com. Retrieved November 26, 2024.

- ^ Asia Society; Chinese Art Society of America (2000). Archives of Asian art. Asia Society. p. 12. Retrieved May 28, 2013.

- ^ Jiang & Chia (2016), p. 21.

- ^ a b Keyworth, George A. (July 2022). "On Bonshakuji as the Penultimate Buddhist Temple to Protect the State in Early Japanese History". Religions. 13 (7): 641. doi:10.3390/rel13070641. ISSN 2077-1444.

- ^ a b Hubbard, Jamie. "A Report on Newly Discovered Buddhist Texts at Nanatsu-dera." Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1991 1814.

- ^ a b Japan Buddhist Federation, Buddhanet "A Brief History of Buddhism in Japan", accessed 30/4/2012 Archived 2020-11-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jiang & Chia (2016), p. 23.

- ^ "Po Lin Monastery". plm.org.hk. Retrieved November 27, 2024.

- ^ a b c Harvey, Peter (2013), An Introduction to Buddhism (Second ed.), Cambridge University Press, Appendix 1: Canons of Scriptures.

- ^ "刊本大藏經之入藏問題初探". ccbs.ntu.edu.tw.

- ^ "No.2". www.china.com.cn.

- ^ a b "East Asian Buddhist Studies: A Reference Guide". www.international.ucla.edu. Retrieved November 26, 2024.

- ^ a b c Catalogue of the Zhonghua Dazang Jing 《中華大藏經》經錄, Digital Taiwan

- ^ "《金藏》劫波 一部佛经的坎坷路(图)_中国网". www1.china.com.cn. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- ^ "說不盡的《趙城金藏》". Archived from the original on June 12, 2010.

- ^ "略谈《中华大藏经》在汉文大藏经史上的地位 -- 佛学讲座 禅学讲座 禅宗智慧 禅与管理 -【佛学研究网】 吴言生说禅". www.wuys.com. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011.

- ^ "《中华大藏经(汉文部分).续编》的特点和结构" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 10, 2011. Retrieved January 23, 2011.

- ^ a b Jiang & Chia (2016), p. 24.

- ^ Li, Fuhua (2020). "An Analysis of the Content and Characteristics of the Chinese Buddhist Canon". In Long, Darui; chen, Jinhua (eds.). Chinese Buddhist Canons in the Age of Printing (Google Play ebook ed.). London and New York: Routledge. pp. 107–128. ISBN 978-1-138-61194-8.

- ^ 工具書‧叢書‧大藏經 Archived 2010-09-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "佛学研究网|佛学论文|首届世界佛教论坛|张新鹰:《中华大藏经》——一项重大的佛教文化工程". www.wuys.com. Archived from the original on March 29, 2009.

- ^ Wenjie Duan (January 1, 1994). Dunhuang Art: Through the Eyes of Duan Wenjie. Abhinav Publications. p. 52. ISBN 978-81-7017-313-7.

- ^ 怀念北图馆长北大教授王重民先生 Archived 2011-07-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "A Research on the Authenticity of the Bhikhuni Seng Fa from Jiangmi 關於江泌女子僧法誦出經" (PDF).

- ^ "一些伪经(作者:释观清)". Archived from the original on May 15, 2007. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "助印佛经须知_昌缘居士_新浪博客". blog.sina.com.cn.

- ^ "zz关于伪经 - 饮水思源". bbs.sjtu.edu.cn. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- ^ 果卿居士《现代因果实录》的不实之处- 般若之门 Archived 2011-07-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Religions". www.mdpi.com. Retrieved November 26, 2024.

- ^ "404". www.cnr.cn.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses generic title (help) - ^ a b c Bingenheimer, Marcus. History of the Manchu Buddhist Canon and First Steps towards its Digitization (Temple University / Philadelphia).

- ^ "Purpose and Projects | Society for the Promotion of Buddhism". www.bdk.or.jp. Retrieved November 27, 2024.

Sources

[edit]- Wu, Jiang; Chia, Lucille, eds. (2016). Spreading Buddha's Word in East Asia: The Formation and Transformation of the Chinese Buddhist Canon. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231171601. Monumenta Serica, 65(1), 223–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/02549948.2017.1309139

- Wu, Jiang; Wilkinson, Greg, eds. (2017). Reinventing the Tripitaka Transformation of the Buddhist Canon in Modern East Asia. Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 9781498547574.

External links

[edit]General

- The Chinese Canon (Introduction)

- WWW Database of Chinese Buddhist texts (Book index)

- (in Chinese) Chinese Buddhist Tripitaka Electronic Text Collection, Taipei Edition

- (in Japanese) Taishō Tripiṭaka, SAT

- Taishō Tripiṭaka, NTI Buddhist Text Reader With matching English titles and dictionary

- East Asian Buddhist Studies: A Reference Guide

- The TELDAP projects as the base of the Integration of Buddhist Archives -- Buddhist Lexicographical Resources and Tripitaka Catalogs as the example

- Digital Database of Buddhist Tripitaka Catalogues

- (in Chinese) 大藏经研究 (Book index)

- (in Chinese) 佛教《大藏经》34种版本介绍保证网络最全 (Book index)

- (in Chinese) 電子藏經 Extensive list of online tripitakas

- (in Chinese) 汉文大藏经刊刻源流表 (Book index)

- (in Chinese) 汉文大藏经概述 [permanent dead link] (Book index)

- (in Chinese) 近三十年新发现的佛教大藏经及其价值 (Description of rediscovered texts of the Canon) (Book index)

- (in Chinese) 历代印本汉文大藏经简介 [permanent dead link] (Description of existing versions of the Canon)

- (in Chinese) 汉文佛教大藏经的整理与研究任重道远 (Description of new versions of the Canon)

Texts

- (in Japanese) Machine-readable text-database of the Taishō Tripitaka (zip files of Taishō Tripitaka vol. 1-85)

- (in Chinese) CBETA Project (with original text of Taishō Tripitaka vol.1-55, 85; the complete Zokuzokyo/Xuzangjing, and the Jiaxing Tripitaka).

- (in Chinese) 佛教大藏經 (links to big size pdfs)

- (in Chinese) 藏经楼--佛教导航

- (in Korean) Tripitaka Koreana (electronic scans)

- Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research, Berkeley provides some English translations from the Taishō Tripitaka (prints or free pdf)

- Bibliography of Translations from the Chinese Buddhist Canon into Western Languages accessed 2013-07-16

- Alternative Source for CBETA

- Buddhist Scriptures in Multiple Languages

- Chinese Canon with English Titles and Translations

- 漢文電子大藏經系列 Chinese Buddhist Canon Series

Non-collected works

- (in Chinese) 報佛恩網 (A collection of many modern Buddhist works outside the existing canon versions)

- (in Chinese) 生死书繁简版 (Another collection of modern Buddhist works)

- (in Chinese) 戒邪淫网 Archived January 25, 2021, at the Wayback Machine (Another collection of modern Buddhist works)

- (in Chinese) 佛學研究基本文獻及工具書 (Book list)

- (in Chinese) 大藏经 (Book list)

- (in Chinese) 大藏经 Archived April 15, 2023, at the Wayback Machine (Book list)

- (in Chinese) 佛教大学 (Book list)

- (in Chinese) 中文佛學文獻檢索與利用 (Book list)

- (in Chinese) 工具書‧叢書‧大藏經 (Book list)

- (in Chinese) Center for Buddhist Studies 國立臺灣大學佛學研究中心 (Book list)

- (in Chinese) 佛教研究之近況 (Book list)

- (in Chinese) 佛書- 佛門網Buddhistdoor - 佛學辭彙- Buddhist Glossary (Book list)

- (in Chinese) 兩岸佛學研究與佛學教育的回顧與前瞻 (Book list)

- (in Chinese) 当代台湾的佛学研究 (Book list)

- (in Chinese) 佛教资料库网站集锦(修订3版) (Book list)

- 美國佛教會電腦資訊庫功德會「藏經閣」

- 七葉佛教書舍

- Chinese buddhism works

- 佛缘正见 Archived August 3, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- 弘化社,佛教印经,经书流通,净土

- 佛教书籍网:佛经在线阅读,佛教手机电子书下载,佛学论坛,佛经印刷

- 妙音文库