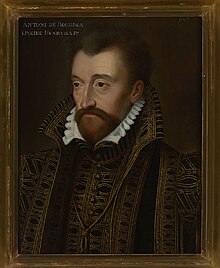

Charles, Duke of Vendôme

| Charles de Bourbon | |

|---|---|

| Duc de Vendôme | |

18th-century portrait | |

| Born | 2 June 1489 Château de Vendôme, France |

| Died | 25 March 1537 (aged 47) Amiens, France |

| Spouse | Françoise d'Alençon |

| Issue See Wife and children | |

| House | Bourbon-Vendôme |

| Father | François de Bourbon, Count of Vendôme |

| Mother | Marie de Luxembourg |

Charles de Bourbon, duc de Vendôme (2 June 1489 – 25 March 1537) was a French soldier, governor, Prince du Sang and courtier during the reigns of Louis XII and François I. Charles (referred to by his title as Vendôme) was the son of François de Bourbon and Marie de Luxembourg. Beginning his military career in the Italian Wars of Louis XII, he saw service at the crushing French victory of Agnadello in 1509 and the capture of Genoa in 1507. With the death of the king in 1515, he continued his service under François. He was rewarded with the elevation of the comté (county) de Vendôme to the rank of duché (duchy), he was also made governor of the Île de France. He joined the king for his first Italian campaign in 1515. He thus participated in the battle of Marignano. Returning to France he traded his government of the capital for that of Picardie in 1519. It would be in Picardie he saw most of his military service for the rest of his life. He participated in the northern campaigns against first the Holy Roman Empire and then England in 1521 and 1522 respectively. In 1523, his cousin, the duc de Bourbon defected to the Imperial cause. The king feared Vendôme might follow him in his treason and recalled him from Picardie. Thus the vicomte de Thouars led the campaign in the north in 1523. Vendôme, having proven his loyalty, was soon permitted to return north, and he played a role, alongside Thouars in combatting the Chevauchée of the duke of Suffolk that was threatening Paris in the Autumn. In late 1524 the king departed France to conquer Milan. His campaign ended in disaster at the battle of Pavia at which he was captured.

Vendôme had been entrusted with the defence of Picardie during the king's absence, and was not at Pavia. Thus he had a key role to play in the regency government of the king's mother Louise. Along with several other key military figures he was responsible for the defence of the kingdom at a very sensitive moment. He had also become the premier prince du sang with the death of the duc d'Alençon, putting him fourth in the line of succession. He was frustrated by his situation, as though he was the nominal chair of the royal council in Lyon, he was unable to prevent Louise favouring the vicomte de Lautrec over him and snubbing his wife's rights to the Alençon inheritance. Nevertheless, though a faction in the Paris Parlement wished for him to usurp the regency, he did not put himself at the head of an opposition party. In 1526, François was conditionally released from his captivity and the regency ended. With it ended Vendôme's central position in the government. In the coming years he was present for many important ceremonies, such as the king's special sessions of the parlement, meetings with the English and the release of the king's sons from captivity. In December 1527 he led the nobility at a meeting called by the king to endorse his breaking of the terms of the treaty of Madrid by which he had secured his freedom after Pavia. He assured François on behalf of the nobility that they would devote their lives and property to him.

A new crisis emerged for the kingdom in 1536. Vendôme worked to secure funds for his soldiers in Picardie, and came into conflict with the cardinal du Bellay who the king had placed in charge with Paris. Vendôme was frustrated by the quality of his troops, and what he felt were insufficient exertions by du Bellay to support him. The Imperial siege of Thérouanne would fail, and with it the crisis passed. Vendôme was again involved in the campaign of 1537, however he came over ill in March and died in Amiens on 25 March. His grandson would become king of France as Henri IV.

Early life and family

[edit]

Charles de Bourbon was born on 2 June 1489, the son of François de Bourbon, comte de Vendôme, and Marie de Luxembourg, dame de Saint-Pol.[1][2][3][4]

The house of Bourbon had its origins in the sixth son of king Louis IX, the comte de Clermont (count of Clermont). Vendôme was a direct agnatic (through the male line) descendant of Louis IX through Clermont.[3][5] His mother, Marie, was the granddaughter and heir to the disgraced connétable de Saint-Pol who was executed in 1475.[6] Though the lands held by the Luxembourg connétable had been confiscated, in 1487 the lands were returned to Marie for the occasion of her marriage.[7] From his mother therefore, Charles would inherit many Picard lands, among them: La Fère, Ham and Condé-en-Brie. She also brought him Flemish fiefs, including Enghien, though these revenues would be confiscated by the Holy Roman Emperor.[1] The Bourbon territories in Picardie would be governed from the château de La Fère.[8] The strong position inherited by Charles in Picardie through his mother granted the Bourbon-Vendôme a position in Picardie that no other seigneur (lord) could challenge. In addition to her land, was their status as princes du sang, which ultimately made first Charles de Bourbon and then his son's control of the governorship inevitable.[9] The marriage of François and Marie was made at the direction of the king Charles VIII and would transpire in February 1488.[10] By means of the marriage, the king hoped to tie the Luxembourg families interests to those of the junior royal branch (the Bourbon-Vendôme).[7]

Charles had four siblings from his parents marriage, among whom were two brothers:[11][7]

- François de Bourbon, comte de Saint-Pol (1491–1545).[12] Saint-Pol would serve as the governor of Dauphiné.[13][11]

- Louis de Bourbon, cardinal de Bourbon (1493–1553).[11]

Charles' sister Antoinette de Bourbon, married the comte de Guise (a member of the house of Lorraine), who in 1524 was made the governor of Champagne and then in 1527 became the first duc de Guise and a pair de France (peer of France).[14][13] Charles' other sister became the abbess of Fontevraud.[15]

Upon the early death of François in 1495, Marie was left to administer both her own lands, and the comté de Vendôme (county of Vendôme) of her late husband. She would remain a widow until her death in 1546, devoting herself to the administration of her estates in Picardie (region of north east France).[7] She was an active manager of these estates.[16]

Wife and children

[edit]

On 16 May 1513, Charles married Françoise d'Alençon, the widow of the duc de Longueville, at Châteaudun. She was the daughter of René de Valois, duc d'Alençon and Marguerite de Lorraine.[4] She was also the sister of the premier prince du sang (first prince of the blood - closest agnatic relative to the king outside the royal family) Charles de Bourbon, duc d'Alençon. This created a connection between the two subordinate branches of the royal house.[17] His wife brought the baronnies de Château-Gontier, La Flèche and Beaumont-sur-Sarthe with her to the marriage.[1] On the occasion of the marriage, his mother Marie declared him to be her principal heir, and he was granted 8,000 livres annually. Marie would continue to enjoy the usufructs on her properties for the remainder of her life however.[15]

His wife would outlive him, dying in 1550.[11]

With Françoise d'Alençon he would have thirteen children:[12]

- Louis de Bourbon (23 February 1514 – 7 April 1516) comte de Marle.[4]

- Marie de Bourbon (29 October 1515 – 28 September 1538), prospective bride for the king of Scotland.[18]

- Marguerite de Bourbon (26 October 1516 – 20 October 1559), married the duc de Nevers with issue.[12][18]

- Antoine de Bourbon (22 April 1518 – 17 November 1562), duc de Vendôme then king of Navarre, married Jeanne, queen of Navarre, their son Henri would ascend the French throne as Henri IV in 1589.[12][1][3][5][19]

- François de Bourbon (23 September 1519 – 23 February 1545), comte d'Enghien.[1][20]

- Madeleine de Bourbon (3 February 1520 –) abbess of Sainte-Croix de Poitiers.[18]

- Louis de Bourbon (3 May 1522 – 25 June 1525).[20]

- Charles de Bourbon (22 December 1523 – 9 May 1590), cardinal de Bourbon, king Charles X for the Catholic Ligue (League) from 1589 to 1590.[12][18]

- Catherine de Bourbon (18 September 1525 – 27 April 1594), abbess of Notre-Dame de Soissons.[18]

- Renée de Bourbon (6 February 1527 – 9 February 1583), abbess of Chelles.[21]

- Jean de Bourbon (6 July 1528 – 10 August 1557), comte de Soissons then duc d'Estouteville, married Marie de Bourbon, duchesse d'Estouteville.[12][18]

- Louis de Bourbon (7 May 1530 – 13 March 1569), prince de Condé, married first Éléonore de Roye and upon her death Françoise d'Orléans with issue.[12][1][22]

- Éléonore de Bourbon (18 January 1532 – 26 March 1611), abbess of Fontevraud.[21]

During 1535, he sought a match for his daughter Marie with James, king of Scotland. Concurrently to this endeavour there was a royal project to see the Scottish king married to king François' daughter Madeleine de Valois.[23] It was François' project, rather than Charles' which succeeded, though the royal marriage would be a brief one, due to the early death of Madeleine.[24][18]

Incomes and property

[edit]

The royal pensions enjoyed by the Bourbon-Vendôme grew from the figure of 2,000 livres in 1482 to 14,000 livres in 1525, then 24,000 by 1532 near to the end of Vendôme's life.[25]

While there is much visible in the historical record for lines of credit extending from officers to 'grandees' (such as Vendôme), the historian Hamon argues our visibility of the reverse is far more obscure. He notes one such case in a loan made by Vendôme to a certain 'Jehan de La Forge' for a sum of 1,200 livres in 1524.[26]

Charles possessed a 'beautiful' hôtel (grand town house) in Cambrai which would serve as a residence for the queen mother Louise during the negotiations of the Treaty of Cambrai in 1529.[27]

Aristocratic connections

[edit]The Bourbon-Vendôme family, chief among them Charles served as the protectors of the du Bellay family which would rise to great prominence in the early sixteenth-century. The future cardinal Jean du Bellay would dedicate several works in his youth to the family.[28]

In 1531, Guillaume du Bellay, seigneur de Langey, married Anne de Créquy of the important Picard noble family. Vendôme, the king François and the Grand Maître de Montmorency (Grand-Master Montmorency) all gave their blessing to the match.[29]

Vendôme would enjoy strong ties with the vicomte de Thoaurs (viscount of Thouars), and the two would be companions in arms during the 1520s.[30]

Vendôme would forge connections with the Picard house of Humières. Jean II d'Humières would act as a godfather to the princes son the comte d'Enghien.[31]α

The Italian explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano, in his travels along the North American coast, would name a topographical feature after Vendôme (as well as others after many other great French nobles).[32]

Compagnies d'ordonnance

[edit]

Both Vendôme, and his brother Saint-Pol would serve as capitaines for compagnies d'ordonnance (largely aristocratic companies of heavy cavalry that formed the building blocks of the royal army).[33] Vendôme enjoyed the successive service of the seigneur de Vervins (who joined with his compagnie during Vendôme's service in Italy), the sieur de Canny (1523) the sieur de Moy and the sieur de Torcy as his lieutenants.[34][35] The sieur de Moy was a subject of Vendôme's mother Marie for his baronnie.[36] Torcy meanwhile, was entrusted with various special tasks by Vendôme such as the restitution of property under the terms of the treaty of Madrid in 1526.[37]

Reign of Louis XII

[edit]

The comte de Vendôme (count of Vendôme) gained military experience in the campaigns of Louis XII.[15] He participated in the siege of Genoa in 1507.[4]

The comte de Vendôme fought in the victory of Agnadello against the Venetians in 1509. At the battle he was knighted by Louis.[4]

The queen of France, Anne died on 9 January 1514. Louis wished for to enjoy an elaborate funeral. During the period of mourning, Louis worked to prepare a new campaign into Italy, seeing opportunity in the weakness of the duca di Milano (duke of Milan).[39]

During May, a marriage was celebrated between Louis' daughter Claude and the comte d'Angoulême. Concurrent to this he looked to negotiate a peace with England. One of the terms of this agreement was marriage between Louis and the young English princess Mary. The marriage was drawn up on 7 August, and she arrived in Calais on 3 October. The vicomte de Thouars (viscount of Thoaurs) and the sire d'Orval were dispatched to greet the princess. It would be the comte de Vendôme however who would receive her in the name of the king. She had an elaborate retinue with her, comprising two thousand horse and two thousand archers. Many of the greatest nobles of England were also among those with her, including the duke of Suffolk.[39] Only a few days later on 11 October, the marriage would be celebrated.[40]

Death of the king

[edit]After a period of agonies, Louis XII died in the late evening of Monday, 1 January 1515 in the hôtel des Tournelles (hôtel meaning a grand townhouse) in Paris.[41][42]

His bedside was crowded by many of his faithful companions as well as princes du sang (agnatic male relatives of the king) including the comte de Vendôme, his brother the comte de Saint-Pol, the duc de Bourbon (duke of Bourbon), the comte de Dunois and the vicomte de Thouars . The bishop of Paris was also present, accompanied by mendicant friars and English officers.[41][43]

On 10 January, the king's funeral was held in Paris. Behind the hearse walked four of the princes du sang: the duc d'Alençon (of the Valois-Alençon), the duc de Bourbon and the vicomte de Châtellerault (of the Bourbon-Montpensier) and the comte de Vendôme (of the Bourbon-Vendôme). On 11 January the funeral cortège proceeded to Saint-Denis for the burial ceremony.[44]

In the absence of a son, Louis' cousin and son-in-law, the duc de Valois (formerly the comte d'Angoulême) succeeded to the throne, assuming the name François I.[45] His ascent represented a continuity as opposed to a radical palace shakeup. The various officers of the crown were confirmed in their positions, from the parlements (most senior sovereign courts) to the governors.[46] The new king lacked much in the way of a party of his own, and therefore the royal councils were occupied by many of the men who had been present during the reign of Louis: the comte de Vendôme, the duc de Bourbon, the duc d'Alençon, the vicomte de Châtellerault, the maréchal de Trivulzio (marshal of Trivulzio) who had participated in all Louis' campaigns and the duke of Albany who Louis had elevated to the marshalate in 1514.[47]

Vendôme would be permitted by the new king to address the latter as 'monsieur'. According to Brantôme, when Vendôme's brother, the comte de Saint-Pol attempted to address the king likewise, he was told the privilege of this address extended only to Vendôme and not to he.[48]

Reign of François I

[edit]

Conseiller

[edit]During the reign of Louis XII, men of bourgeois extraction, like Étienne de Poncher, Jean de Ganay, Jacques de Beaune and Guillaume Briçonnet (respectively a bishop, the chancellor, and two généraux des finances - generals of the finances) had enjoyed places of influence on the conseil du roi.[49] As the 1520s wore on, French nobles of prestigious pedigree began to usurp their place in royal affairs, with Vendôme one of them, alongside the comte de Guise, baron de Montmorency, and cardinal de Tournon among others.[50]

In total, princes like the comte de Vendôme would comprise around 15% of the 33 noblesse d'épée (sword nobles - old nobility who associated their class with military service) on the council during the reign of François I.[51]

The historian Michon argues that figures in council like Vendôme, the duc de Lorraine, and the connétable de Bourbon (connétable or Constable, most senior military office in the kingdom, he is also referred to by his title as the duc de Bourbon) were present on the royal councils primarily as a tool of legitimisation. Michon classifies Vendôme, by virtue of his status as a prince and later a duc as a born adviser to the crown.[52] Thus, alongside other similar men like Alençon, the king of Navarre, the duc de Bourbon, and the cardinal de Bourbon they were frequently called to council, even if none of these men had political weight.[53] These great men's illustrious signatures legitimised decisions in which they lacked either political influence or major involvement.[54][55] Vendôme did not have a presence on the more exclusive conseil privé (privy council) outside of the crisis years of 1525-1526.[56]

The historians Rentet and Michon have catalogued those figures present on the royal councils during the reign of François I, dividing the figures into principal members of the council, and those who were also present. Vendôme figures as a presence on the council during 1515-1516, 1518, 1524, 1527-1528, 1530, 1534 and 1537; in their estimation he is elevated to the rank of a principal person of the council during the crisis of 1525.[57]

François quickly set to work distributing favours on those who had been close to him in his youth. The vicomte de Thouars received the admiralty of Guyenne and Bretagne, the seigneur de Boisy (lord of Boisy) was made Grand Maître (great office of the crown and head of the king's household with various privileges), and the comte de Vendôme received the dual honour of being made governor of Paris and governor of the Île de France (the region around Paris).[58] He acceded to the latter charge on 18 February.[59]

As governor of the city of Paris, Vendôme was responsible for the defence of the city. He was one of the authorities who maintained order in the capital (alongside the parlement and the bureau de la Ville. Along with the parlement, Vendôme was a conduit for royal commands.[60]

Governor of the capital

[edit]In February, after his coronation, François made a grand entry into Paris.[61] Various spectacles were put on in the city to mark the occasion, including one where the king was represented in his regalia surrounded by two women one 'France', the other 'Faith'. Around these three figures were six armoured figures whose heraldry identified them as the duc d'Alençon, the duc de Bourbon and the comte de Vendôme. Further figures represented the common people, loyalty and vigilance. The display also featured a brief text concerning David's triumph over Goliath.[62]

In March 1515, the comté de Vendôme (county of Vendôme) was elevated to the rank of a duché (duchy) by François as a reward for the prince's military service.[1] This separated the territory from its dependant status on the duché d'Anjou, a matter which had long been a campaign of Vendôme's mother Marie.[63][15] Concurrently Vendôme also became a pair (peer).[5]

Vendôme undertook a diplomatic mission to Flanders in 1515 so that he might liaise with the lord of the Netherlands (the future Holy Roman Emperor Charles V).[64] He was accompanied by the diplomat the seigneur de Langey whose services he may have recommended to the crown.[65]

In the Autumn of 1515, the French had success in their military advance into Italy. The Imperial (i.e. Holy Roman) commander Colonna was bested by the maréchal de La Palice at Francavilla. The king and royal army followed La Palice over the Alps into Italy, and La Palice and the seigneur de Genouillac were ordered to capture Novara. Little desiring a sack, Novara surrendered to La Palice, and the maréchal was appointed governor of the city. At the Battle of Marignano, François achieved a capital success. Vendôme fought with the king in this battle, and his horse was wounded by pike blows in the combat.[4] Writing to his mother Louise on the evening of the victory the king cited the presence of various nobles, among them Vendôme, his brother the comte de Saint-Pol, La Palice, and the comte de Guise.[66] Vendôme's brother Saint-Pol would come in for particular praise for his valour, with Vendôme being considered a somewhat second rate commander by the king.[67]

Concordat of Bologna

[edit]After this great triumph, it was subsequently agreed that a meeting would take place between François, and the Pope in Bologna. The Pope arrived for this meeting accompanied by many cardinals and soldiers on 8 December 1515. The king arrived three days later with a grand company.[68] François and his chancellor Duprat emphasised their devotion and loyalty to the Pope, alongside the king's willingness to lay down all that he had in service of the Pope. Through one of his cardinals, the Pope thanked François, and named him the eldest son of the church, a recent title which had first been granted to Charles VIII in 1495. François' predecessor Louis XII had not been granted the title. The two men then got down to business, discussing plans for a crusade against the Ottomans, the claims of the French crown to the kingdom of Naples, and in particular the supersession of the Pragmatic Sanction (1438 agreement by which the French church became largely autonomous from the Pope) with a new Concordat. Duprat would spend several days working on the nature of this Concordat with the cardinals (Ancona and Santi-Quatro).[69] The various ambassadors in Bologna were troubled by the new alliance between the Pope and France. François worked to reassure those of Spain, Venice, the Swiss cantons and Portugal. The Pope would do likewise. After a supper, debate took place on the nature of the Concordat, with François affable on many points. In return for his generosity, the Pope conceded to withdraw his troops from Verona on condition of Venice being prohibited from returning to Ravenna and Cervia. At François' request on 13 December, the Pope raised the brother of the Grand Maître to the cardinalate. In the evening François and the Pope dined alongside the duc de Bourbon, the duc de Vendôme and three cardinals. The Pope agreed to remove a censure on the French clergy, and in return François granted the release of the condotierri (originally a term denoting mercenary captains but broadened over time to all Italian commanders) captain Colonna and a postponement of his campaign into Naples. He was more vague on his commitments as concerned a crusade.[70]

On 14 December, François departed Bologna, content in the success of his mission. He had secured leadership of the potential crusade, been granted the title of 'eldest son of the church' and strengthened his alliance with the Papacy. The Pope for his part could feel happy to have subordinated the French to the Roman church through the establishment of the Concordat (which he anticipated would replace the Pragmatic Sanction), delayed any French aggression against Naples and incubated the possibility of a crusade. Vendôme and the comte de Guise led an embassy to the Doge of Venice to inform him of the outcome of the meeting in Bologna. The rough Concordat of Bologna that had been negotiated took the following form: elections to ecclesiastical benefices were to be suppressed. In their stead, the king would nominate within six months of a vacancy opening, either a university graduate or a nobleman of the age 27 or more for churches. This candidate would then receive the approval of the Pope.[71] Milan was de facto recognised as a French territory, and he was given permission to have the décime (tithe - one tenth religious tax) raised at a rate of his discretion, as long as part of the sum went to Rome to fund the building of the Basilica di San Pietro. The sovereign authority of the Papacy was to be recognised absolutely. Various other smaller matters were also discussed.[72]

A great mock battle was staged at Amboise in April 1518, with six hundred men under the command of François and the duc d'Alençon commanding the defence of a model town.[73] Leading the attack in this staged combat was the duc de Bourbon and duc de Vendôme, in command of an equal number of soldiers. The combat received the effusive praise of the seigneur de Fleuranges. The fake combat nevertheless terrified some, and was responsible for the deaths of others.[74]

Frontier governor

[edit]Governor of Picardie

[edit]In December 1519, upon the death of the seigneur de Piennes, Vendôme acceded to the position of governor of Picardie.[75][10] On 16 December 1519, the duc de Vendôme was relieved of his charge as governor of the Île de France. With some brief interludes, he would hold the charge of governor of Picardie until his death.[76] The Île de France was handed over to his brother the comte de Saint-Pol who became governor the same day.[67][59] Unlike other grandee governors such as Montmorency, who was rarely to be found in his charge of Languedoc, Vendôme would spend much time in Picardie during his governorship.[77] In particular, according to the analysis of the historian Potter, Vendôme spent the majority of time in Picardie (either in the province generally or his seigneuries such as La Fère) every year from 1520 to his death with the exceptions of 1525-1526, 1530, 1533 and 1534.[78] There would be significant military coordination between the governates of Picardie and his former charge of the Île de France after 1521.[10]

Due to the quasi-royal nature of the office of governor, great ceremonial entries were made for when the governor first visited a town. This was the case for Vendôme in Abbeville in February 1520 several barrels of wine were prepared for the occasion, the armed companies of the town made ready to greet him. Subsequently the keys were formally presented to Vendôme.[79]

For the first two years of his administration of Picardie, he would have no deputy governor in Picardie.[80] As far as the captaincies of the greater towns of his province were concerned, many were quasi-hereditary. For example Amiens was captained by three generations of the Lannoy family from 1495 to 1562. In Beauvais, the baron de Montmorency was succeeded in 1515 by his son the sieur de La Prune au Pot (later to take the name of the sieur de La Rochepot). Saint-Quentin was handed through members of the Mouy family and Abbeville by several generations of the Haucourt de Huppy Family. Montreuil was held by the sieur de Pont-Rémy who would serve as Vendôme's deputy in the coming years.[81] In addition to generational occupation, proximity to Vendôme could also secure nobles their town governorships. For example a noble named Montbrun of his household was established as governor of the town of Guise in 1527.[82]

He quickly aroused the umbrage of the grandees of Beauvais when he sought to install a garrison of 50 lances in the city. They rebuked him for this claiming they were not part of his Picard government but rather that of the Île de France. Thus, they sent a deputation to Saint-Pol. Saint-Pol responded to the delegation that the king would make Vendôme understand Beauvais was not under his authority and relieve them of the garrison. This would not be the end of the dispute between Beauvais and Vendôme. In May 1524, he again tried to garrison the city much to their chagrin. Nevertheless, when legionaries caused havoc around Beauvais in 1536, they appealed to Vendôme to relieve them of their depredations.[83]

The consuls of Tournai attempted to circumvent Vendôme's intermediary authority in 1521 and make an appeal straight to the king. Vendôme expressed his great frustration to them after this episode, suggesting it implied to him that they did not trust him.[84]

La Fayette dispute

[edit]In the early summer of 1521, Vendôme also fell into a dispute with the seigneur de La Fayette who had served as the governor/captain of Boulogne since 1513. Vendôme charged the governor with having undertaken raids of Bourgogne without permission. He argued that Thérouanne needed supplies before it could be engaged on an offensive footing. La Fayette's actions had been reported to him by the government of Montreuil, and in August the prince wrote to La Fayette prohibiting him from selling any loot he might have acquired. La Fayette was vexed by these chastisements and escalated the dispute to court, sending a representative that accused Vendôme and the maréchal de La Palice of not being honest in their concerns, arguing that their prime opposition to him came from their fears of losing their Burgundian territories once war began. He went on to say that Vendôme was jealous of the governors three ships, that had been equipped as the seigneurs expense.[85] La Fayette would ask to be relieved of his governorship in 1522, and it was provided to the seigneur du Biez who subsequently usurped La Fayette's control of the broader sénéchaussée (region subject to the jurisdiction of a sénéchal - seneschal) in January 1523. La Fayette was close with Vendôme's cousin the connétable de Bourbon, whose treasonous dealings were already suspected at this time. Potter speculates this might be the cause of his dismissal from the latter charge.[86]

In April 1521, the duc de Bourbon's wife Suzanne died. She had willed all her property to her husband. King François and his mother Louise were determined to frustrate the succession of her territories.[87]β

Campaign of 1521

[edit]

During the campaign season of 1521, François snubbed the connétable de Bourbon by denying him command of the army for Italy, the most prestigious command, granting the honour to the vicomte de Lautrec. Bourbon was instead put in charge of the army in Champagne.[88] François furthered this snub by installing Vendôme at his side, in a role Jacquart describes as being like that of a supervisor.[89]

The military endeavours of the summer went poorly for François. For want of money his plans had either ended in defeat or postponement. There was now a risk that Mézières, in Champagne would fall to the Imperial army, and with its fall much of Picardie would be opened to the forces of the Emperor. Such an eventuality was not tolerable.[90] The Imperial army, under the command of the graaf van Nassau subdued Mouzon before turning its attention to the capture of Mézières.[91]

François, keen to avoid this eventuality, saw to it that 2,000 men were dispatched into Mézières at the end of August, most notable among them being the maréchal de Montmorency, the famed captain the seigneur de Bayard, and the future amiral de France the seigenur d'Annebault. The city was put to siege by the Imperial army whose formidable artillery set to work on the walls. Though the city initially resisted well, food quickly ran low, and disease spread. Thus, the king, operating out of Reims, ordered the cities resupply. At this time, François was also assembling a large force in Reims, sending out orders to the gendarmerie of Bourgogne and men of his household to come to the city. Further to this Vendôme was to gather 10,000 infantry and 200 cavalry around Saint-Quentin and Laon, and the duc de Bourbon to join with the king in Reims at the head of roughly another six thousand infantry and 200 cavalry. A small force bringing supplies under the command of Vendôme's brother the comte de Saint-Pol arrived on 23 September, dashing the hope of the Imperials to subjugate the city by starvation alone. Conditions outside the walls were just as dire as inside, and not long after, on 25 September, the Imperial force was ordered to make a retreat from the city. In addition to the poor conditions, Nassau was aware of the imminent arrival of a large royal army under François' command.[92][93]

In August 1521, Vendôme wrote to the secrétaire Robertet requesting that he be affirmed in the right of a governor to allocate territories confiscated from the kingdoms enemies. He cited the example of the maréchal d'Esquerdes who had enjoyed this right during the conflicts of 1477. By this means, Vendôme would have the power to both assure himself of his own compensation and those of his loyal followers.[94]

As was the custom for the provisioning of frontier forces, Vendôme made demands of supplies from the towns of Picardie. This would be followed in October 1521 with requests for more wine and bread. Beauvais was to provide 50,000 loaves of bread in September, and Abbeville to provide 10,000 loaves a day until he told them otherwise.[95] Such demands could generate protest, as in April 1524 when Chauny noted that if it provided its grain supplies there would be none left for the people of the town.[95] In the 1530s, Vendôme and La Rochepot had to assail the towns with their requests for supplies. For example, on 3 July 1536 he demanded 4000 loaves a day from Chauny, the town protested and he altered his request to 3000 loaves a day and five pieces of wine for the soldiers encamped at Assis-sur-Serre. With nothing coming still, Vendôme chastised the town and reverted his request to 4,000 loaves. Come the end of July no bread had been provided from Chauny. The governor of Chauny thus informed the town of Vendôme's anger on 11 August and the supplies were brought north.[96]

On 4 October, François was at Attigny where he reviewed his Swiss troops. The intention was for them to march to the relief of Tournai, which was under Imperial siege. However, the weather turned, and there was torrential rains. This, coupled with the destruction caused by Nassau's retreat frustrated progress.[93]

Success in front of Mézières proved a welcome morale boost for the French army after a difficult summer. François looked to seize the initiative and put himself at the head of an army of 30,000 men to lead a pursuit of the retreating Nassau. The Imperial commander was moving towards Montcornet with the intention of besieging Guise.[92]

The duc de Vendôme was dispatched to occupy Vervins so that he might impede the Imperial retreat. Vendôme's brother seized back Mouzon on 3 October (which had previously fallen to Nassau). Nassau now changed his plans, and after putting Aubenton to the sword, he made for Estrées, carving a path of destruction in his wake.[93] Despite the French successes on the Picard frontier, and in the south of the kingdom (where the amiral de Bonnivet was profiting), the Emperor would not countenance establishing a truce or a peace with the French. He opined that until such time as France returned to him Dauphiné, Bourgogne, Provence, Montpellier, Asti, Milan and parts of Roussillon, there could not be a peace. This was in itself a moderation of his claim to the entire kingdom of France, that he asserted was his by right of a Papal decision in 1303. The Emperor's ally, the English were less bullish about their prospects, and looked to obtain a several year truce.[97]

From camp at Origny on 12 October, François responded to the English truce proposals. A truce would be granted only if it included the entire coalition, lasted four to five years, compelled the Emperor not to visit Italy, provide money to the king of Naples, return the kingdom of Navarre to its despoiled king and saw to it that the Emperor reaffirm his intentions to marry his daughter Charlotte de Valois.[97]

With these terms quite impossible, François and the French army set off in pursuit of Nassau. On 19 October, in battle formation, they marched towards Valenciennes. According to the historian Le Fur, the duc d'Alençon led the vanguard, the king and Bourbon were in the battle, and the duc de Vendôme led the rear-guard.[98] It was traditional to assign the vanguard to the connétable.[99] According to Hamon, Bourbon was with Vendôme in the rear-guard. He adds that Bourbon was doubly aggrieved both by his lack of command and that his tactical advice was ill listened to.[100][89] After receiving troubling reports that those in Bapaume were engaged in troubles, François dispatched the comte de Saint-Pol, the seigneur de Fleuranges and the maréchal de La Palice to Bapaume, which they stormed and then torched and razed. Vendôme replicated his brothers treatment of Bapaume at Landrecies on 22 October, razing the settlement.[101]

With the French army now in Imperial territory, the Emperor had resolved to meet the invaders on the field. By 22 October he was at Valenciennes. In the opinion of Knecht, the French had the opportunity at this time to strike a major blow against the Imperials.[98] The possibility of making battle was considered by the French, and to this end a bridge over the Scheldt was to be constructed. The Emperor dispatched 16,000 men to interfere with this work, but they found the comte de Saint-Pol's men already in battle order, and the French vanguard not far behind him. Debate now followed as to whether to engage in battle, with the duc de Bourbon, the vicomte de Thouars and the maréchal de La Palice in favour, and the maréchal de Coligny among those who opposed. François sided with those who were against giving battle. That night, the Emperor withdrew from Valenciennes with 100 light horse. Despite his opposition to battle, François permitted his captains to pursue the Imperial force towards Valenciennes.[101]

The French commanders set about securing the surrounds of Valenciennes: the duc de Bourbon seized Bouchain and the duc de Vendôme surprised Somain.[102]

Meanwhile, Nassau's army moved off to join the siege of Tournai. Rather than relieve Tournai, the royal forces burned the town of Hesdin despite the wealth that the French troops fancied in the town. The châteaux de Renty and Bailleul-Mont were also seized by the French.[102]

On 1 November, the king began the retreat towards Arras, and the royal army was disbanded for the winter on 9 November at Amiens.[103]

Come mid November, François had withdrawn to Compiègne where he reunited with the queen and Louise.[102] His failure to give battle was a source of some embarrassment, as not only had he declined it before Valenciennes, but several days later when offered battle before Bouchain by the graaf van Nassau, he had again refused it. In addition to these failures, negotiations with England were struggling to progress (with the looming threat of the English king Henry VIII joining with the Emperor in military alliance in November if the French king did not reach an agreement with the Imperial party by that time). and at the end of November, Tournai fell to the Imperial army besieging the city.[104] Compounding this reversal, on 24 November, the English signed the treaty of Bruges by which they committed to join with the Emperor in war against France in 1522.[103] The French texts of the campaign limited themselves to describing the places conquered and the destruction wrought.[105]

Spring campaign against the Imperials

[edit]

While the vicomte de Thouars yearned to be granted the prestigious responsibility of leading the campaign to reclaim Milan for France in the spring of 1522, he was instead ordered to join with Vendôme so that they might both protect Picardie against the newly formed Anglo-Imperial coalition.[106]

In the spring campaign of 1522, a raid from Arras was foiled by the men of the seigneur d'Estrées who caused the Imperial party to return to their starting point empty handed. This reverse occasioned a new imperial action, with Doullens (of which Estrées was the protector) put to siege on 19 March.[107] Vendôme, based out of Amiens, implored his brother Saint-Pol to gather 2,000 Swiss soldiers who were garrisoning Abbeville and lead them to Doullens. The Swiss troops would however refuse to fight, citing lack of pay, and they returned to the mountains. Thus, Saint-Pol instead demanded 1,000 soldiers from Hesdin. With this troop assembled, the besiegers of Doullens were scattered.[108]

Come the end of April, various bands on the border, for want of food, were causing havoc for Vendôme. He resolved on a radical solution, having several fortresses razed, and putting the land to fire around Arras. Once Vendôme had returned to Doullens he was appraised of the movements of an English army. Henry VIII was assembling a force at Dover intending to land in Calais.[108]

War with England

[edit]Relations between the two crowns had been difficult since the collapse of negotiations between the crowns in 1521. Nevertheless, François had not entirely cast down the prospect of attempting friendship with the English king. Though François was interested in friendship, he had not paid the money he owed to the English crown since May 1521. He had further cut off the pensions that were afforded to several English princes, including the duke of Norfolk and the cardinal Wolsey. After complaints from the English king, in January 1522, François assured Henry he would abide by his promises. February came and went without payment, François writing to Henry, characterising the Emperor as the aggressor in the Franco-Imperial conflict, and asking for the English king's support.[109]

On 23 May, the Holy Roman Emperor was to be found in Bruges. He travelled to Dunkerque on 24 May, then Calais the day after. He was at Dover on 26 May where he met with the cardinal Wolsey and soon thereafter the English king. He would spend the next month in England before embarking for Iberia in July.[110] During his stay in the country, Henry promised a combined invasion of France prior to May 1523, and an English expeditionary force prior to August 1522.[111]

On 28 May, Henry's representative, Thomas Cheney met with François in Lyon. In the hopes of securing his money, a truce was again proposed (for François to make with the Imperials), and if François would refuse this, Henry would assume his claim to be the protector of the Imperial Low Countries and declare war on the king.[108]

The day after, 29 May, Henry's declaration of war was read to François by a herald: the English king complained of the unpaid debts, breaches of the treaty of London, French aggressions against the Emperor, French support for the duke of Albany (an enemy of Henry's in Scotland). François allegedly delivered a quick and scornful response in which he assured that the English would quickly tire of waging war.[112][111]

Anglo-Imperial campaign

[edit]The ban and arrière-ban (service levies on the nobility) were ordered raised in Normandie. The vicomte de Thouars, who had been appointed as Vendôme's deputy in the province during May, departed for Picardie with 2,000 men to supplement Vendôme's forces in the province and reorganise the urban defences.[80] Vendôme's Picard army was still too small to effectively control the whole province, and therefore he concentrated his men on Hesdin, Boulogne, Thérouanne, Montreuil and Abbeville. Meanwhile, he abandoned other sites that were less defensible, such as Ardres.[112] Across Boulogne, Thérouanne, Hesdin, Montreuil and Abbeville the garrisons numbered 12,700 infantry and 705 members of the gendarmerie, with Vendôme and the vicomte de Thouars based out of Abbeville.[113]

From July the English menaced the Breton coast and reeked devastation. François resolved to raise a new tax of 2,400,000 livres to resist the English intrusions into Bretagne without having to deprive the edges of Flanders, Artois, Guyenne and Provence which were equally threatened of their soldiery - something he would have to do without access to these new funds.[110]

Poor weather delayed the English arrival, allowing the French to take the initiative, putting Bapaume to the torch, and pillaging and burning villages across Artois to compromise the ability to supply forces in the region. This accomplished the soldiers returned to their garrison towns.[112] Even slower than the English soldiers were their supplies. Vendôme's brother Saint-Pol and the comte de Guise were tasked with containing the English force and they advanced to Desvres and Samer before the English were reunited with their supplies.[110]

In Picardie, the earl of Surrey and duke of Suffolk took command of the English forces. They marched out of Calais in September, looking to provoke the French into battle.[111] Linking up with the graaf van Buren (count of Buren) they easily conquered the area between Saint-Omer and Ardres. This was accomplished with few fruits however, and their destruction of the Boulonnais countryside failed to induce Vendôme to battle, the prince simply rebuking the English for their 'foul warfare'.[114][111][115] Thérouanne, where the seigneur de Brion was holding up with parts of his compagnie d'ordonnance, was put to siege by the English. Vendôme was ordered by the king to relieve the siege. The seigneur de Brion would see to the resupply of Thérouanne while Vendôme held up in Audincthun.[116]

The English-Imperial army then looked to strike at Hesdin, seeing it as the weak link in the defended royal chain of towns. Their batteries set to work on Hesdin, and, despite the efforts of the comte de Guise and a certain Pontdormy after fifteen days, they made a breach. Despite this success, no assault through the breach would be ordered, bad weather and the ferocity of the skirmishes persuading them to disengage in favour of an attack on Doullens, which was torched (along with all the surrounding villages). Saint-Pol had seen Doullens as a liability and had ransacked its food store and pulled down its gate so that he might move to Corbie.[114]

Vendôme shadowed the Anglo-Flemish Imperial army towards the Somme, supported by a force under the maréchal de Montmorency.[114] By the time of All Saints' Day, 1 November, the troops were exhausted, and the rains had been unceasing. The invading coalition army retired to Artois for the winter.[117]

In Le Fur's opinion, the Anglo-Imperial invasion of 1522 had failed to achieve any major conquest, succeeding only in spreading panic across the north of France.[117]

Concurrently to the campaign of Autumn 1522, the connétable de Bourbon had fostered his contacts with the crowns of England and the Holy Roman Empire.[118] Vendôme's brother Saint-Pol worked over the winter to reconcile Bourbon with François.[2]

Calm before the storm

[edit]

In March 1523, the connétable de Bourbon was tasked by the king with undertaking a police mission to suppress various bands of rebes in the Champagne, Brie and Bourgogne. Vendôme, Saint-Pol and the vicomte de Thouars were entrusted with working with him on this operation.[119] Bourbon also oversaw the resupplying of Thérouanne in the company of the Vendôme brothers.[120]

Just before Easter 1523, the campaign in the north began again with a Flemish army numbering around 12,000 making an attempt on the town of Guise. The seigneur de Fleuranges commanded the nearby royal army, but François did not wish to give battle. Fleuranges withdrew to near Sedan on the border, and Vendôme was tasked with seeing Thérouanne kept in supply. The town was menaced by Imperial forces lodged in Audincthun and Delettes. Vendôme boasted a force of around 4,000 landsknechts, roughly equivalent numbers of Picard soldiers, strong artillery and 500 hommes d'armes. He took charge of the road to Saint-Omer to strangle Imperial supplies and soon caused the Flemish army to scatter. He pursued the retreating Flemings along the Scheldt river repeatedly skirmishing with them, while tasking the seigneur de Brion with bringing food supplies into Thérouanne from Montreuil.[121]

The defence of Picardie was a concern on Vendôme's mind in June. Vendôme looked to bolster the defences of Thérouanne in particular. To this end the acquisition of oats, salt and other provisions were made that required the requisitioning of horses from as far away as Normandie to bring into the town. This provisioning effort cost around 6,500 livres'. This sum was paid for by the king's secrétaire, upon Vendôme's instruction.[122]

François showed little apprehension about affairs on the northern frontier, viewing the Flemings as poor soldiers, and the English as insufficiently numerous to pose a threat. He declared the counties of Flanders and Artois to be confiscated from the Emperor and then ordered the blockading of the Calais harbour.[121] The duke of Albany was tasked with entering Scotland and making war with the English as soon as possible on their northern frontier, to which end he was granted 100,000 livres. These security decisions taken, he thus felt comfortable peeling off much of Vendôme's forces in the province, leaving him with only 2,000 infantry and 780 lances, so that he might employ the rest for the kingdom's Italian campaign. The maréchal de Montmorency took much of Vendôme's former army south to Lyon.[123]

Treason

[edit]By the summer of 1523, word was reaching the queen mother Louise of the nefarious intentions of the connétable de Bourbon. On 26 July, a certain capitaine named La Clayette informed her that Bourbon had installed 50 hommes d'armes (men-at-arms) in his fortified holdings of Chantelle and Carlat and was mustering victuals and artillery.[124] Bourbon had during July reached an agreement with the Emperor to marry the latter's sister and to betray France at the moment that England and the Empire invaded the kingdom.[118]

With an understanding of Bourbon's coming betrayal now established, royal suspicion fell on many others. Vendôme was a particular focus of royal concern. Both the Emperor and his aunt Margarete, the regent of the Netherlands often discussed the clients and allies of Bourbon who they imagined might follow him in his treason. Chief among the names they floated were the duc de Lorraine, the king of Navarre and the Bourbon-Vendôme brothers (Vendôme and Saint-Pol).[125] Moreover, both Vendôme and Saint-Pol were close with the connétable. Both their fathers had served as companions in arms during the early Italian Wars. The two families were also linked by marriage.[2] The historian Michon sees the fact that the king would suspect one of his closest favourites (by which is meant Vendôme's brother Saint-Pol) of treason as indicative of the state of the court in 1523.[125]

In a state of alert, the crown dispatched the vicomte de Thouars to Picardie so that he could engage a watchful eye over Vendôme, lest he prove sympathetic to his cousin's treason.[124] Thouars had a particularly notable contempt for the connétable de Bourbon, making him ideal for the mission. In addition to the Vendôme component of his mission, his travel to Picardie would allow him to assure himself of the defensiveness of the province.[126] Though he had a great hostility for the connétable, the vicomte enjoyed warm relations with the duc de Vendôme, and he thus protested to the king the fact he was to replace him.[30] The suspected prince, Vendôme was recalled to the court in Lyon in August.[119]

While staying at Gien, where he had arrived on 12 August, the king made two declarations. Firstly that he was going to campaign in Italy, so that he might secure 'his duchy' (i.e. Milan). The second declaration, a connected one, was that in his absence his mother Louise would serve as regent of the kingdom, as she had done in 1515. Her regency was ratified by the parlement on 7 September.[127] During the king's stay in the city, the seigneur de La Vauguyon cryptically informed him of what he was aware of concerning Bourbon's plan. François is supposed to have replied that were he as paranoid as Louis XI he would have considerable reason to suspect the connétable.[127][126]

While on the road to Moulins on 16 August, François received confirmation of the treasonous dealings of the duc de Bourbon. On 15 August, his mother Louise had received confirmation of the plot in a letter from the comte de Maulévrier (who was the sénéchal de Normandie, and the son-in-law of one of the conspirators, the seigneur de Saint-Vallier). She had promptly written to her son with the information. He had informed the queen mother that a great noble of royal blood was plotting with the kingdom's enemies, and François' life was in danger. A few days previous, François had been appraised of contacts Bourbon had with the English agent Jerningham.[127][126]

François visited the connétable at Moulins, where the latter was convalescing with a fever. He did not imply any awareness of the duc de Bourbon's betrayal, and was assured by the latter that he intended to join with the king for the campaign into Italy. François departed, but left Bourbon under the eye of the seigneur de Warthy.[127]

From Lyon, on 5 September, François struck against the conspirators. He ordered the arrest of Saint-Vallier, Aymar de Prie and the bishop of Le Puy. His suspicions of Vendôme meant that the prince had been recalled from his governate of Picardie in August (leaving Thouars in charge) so that Vendôme might be at his side. The prince was charged with assisting his cousin, the duc d'Alençon in suppressing any potential rebellions that arose in the Bourbonnais and Auvergne.[127]

After his meeting with the king, Bourbon retired to his château de Chantelle, still nominally under the cloud of his illness. By now this was a ruse, and he was preparing to depart the kingdom. On 7 September he wrote letters to many major personages of the kingdom, including the king, and Louise. He offered apologetics for his actions as being justified, arguing he only sought to take what was rightfully his. That night he made his flight from Chantelle and out of France. Though it is difficult for historians to reconstruct his movements over the coming weeks, on 9 October he was in Besançon, then in Italy in December.[128]

The maréchal de La Palice and the comte de Tende had been instructed to make for Chantelle to locate the connétable. However, by the time of their arrival, he had since fled, and they were unable to pursue, not knowing where he had gone.[129]

It was now time for the king to make his response official. On 11 September he wrote a letter urging the bonnes villes (good towns of France) to maintain their loyalty to the crown. A large bounty of 20,000 écus was also offered for the parties who would hand over the rebel duc de Bourbon to the king.[128]

In this dramatic moment, François did not feel in a position to lead his army that was due to cross the Alps into Italy as he had planned. Therefore, command was given to the amiral de Bonnivet. The first contingents crossed the Alps at the end of the summer.[130]

Though his suspicion may have lingered on Vendôme and Saint-Pol for several weeks in the wake of the revelations of Bourbon's betrayal, it quickly passed as it became clear both brothers would remain in their loyalty to the king. François therefore was quick to affirm his trust in them both.[131] In October, Vendôme departed for Paris in the company of the bishop of Aix, and the seigneur de Brion to declare that the king had entrusted him with the security of the capital.[119] He was before the parlememt of the capital on 5 November.[120]

English chevauchée

[edit]

The situation had not remained calm in the north. The duke of Suffolk landed with an army of 15,000 in Calais sometime in July.[123] He linked up with the soldiers under the command of the graaf van Buren as the English had the prior year. This combined force made for Hesdin. To the peasants around Ancre he made a warm offer, inviting them to bring supplies in with promises of safe conduct. By this means he secured markets to sell his army food.[115] The vicomte de Thouars, who was serving as the new lieutenant-général of Picardie, had placed the seigneur de Fresnoy and the seigneur de Pierrepont in Hesdin with 2,000 soldiers. The coalition army would not stop at Hesdin however, marching first to Doullens and then Corbie (where Thouars was based) before passing this in turn. The manpower situation Thouars was faced with was dire and he was forced to juggle his limited soldiers to ensure they were placed in the towns in front of the army of invasion. In mid October, the coalition force seized and plundered the towns of Roye and Montdidier. These yielded significant riches to the sackers.[132]

In late October, the army was now within 50 kilometres of Paris, and was rumoured to be eyeing attacks on Compiègne, Breteuil and Clermont, Oise.[133] On 24 October 1523, Vendôme was restored to possession of the governate of the Île de France, to hold it in parallel with that of Picardie.[67] In his absences from this second governate in the coming years, the power of governor was wielded by the archbishop of Aix.[134] With this new authority at his disposal, Vendôme was thus dispatched to the capital. Several taxes were demanded of the bourgeois to raise a company of archers and fortify the suburbs (an action directed by the seigneur de Brion). Chains were raised across the streets.[133] The two men (Brion and Vendôme) had visited the suburbs facing Suffolk's army several times before resolving on fortifying them.[116] The coalition army soon became aware of Vendôme's presence in the capital, and with him out front, and the vicomte de Thouars behind, they began to fear being sandwiched between them. They thus began a retreat towards Saint-Quentin. Nesle was put to the torch as they retreated, with the army concluding its march in Artois, where Suffolk disbanded the force before All Saints' Day.[132] Come December, Suffolk and the remnants of his army were in Calais.[133] The historian Vissière, drawing on the work of Gunn cites the coming of winter as the reason for Suffolk's withdrawal.[106]

The historian Le Fur sees the campaign as largely a failure, that managed little other than to reconnoitre the road to Paris (describing it as a 'dress rehearsal').[132]

Italian campaign of 1523

[edit]Amiral Bonnivet led the French invasion of the ducato di Milan for François. He had with him around 30,000 men, compared to his Imperial adversaries who had mustered approximately 15,000. According to the historian Le Roux, he also boasted two princes du sang in his ranks: the duc de Vendôme and duc d'Alençon, as well as the maréchal de La Palice. Vendôme cannot have been with the army long, as he was in Paris before October was out.[116] Outnumbered, the Imperial army, led by the condotierri commander Colonna retreated into Milan, with the French army establishing itself before the city at the end of September. Ill inclined to directly assault the well defended city, Bonnivet looked to isolate the city by controlling its surrounds. The famed French chevalier, the seigneur de Bayard failed to secure Cremona for the royal army. Around the end of 1523, the Imperial commander Colonna died, and was replaced by the viceroy of Naples de Lannoy. Lannoy looked to attack the French supply lines rather than confront the invaders directly. In early 1524 the French army under Bonnivet withdrew towards Novara, with his troops beginning to desert him.[135] As the army was crossing the river Sesia, northwest of Novara, the Imperial force leapt on them. The French rearguard was forced back, and Bonnivet, wounded, was evacuated back to France. Command of the French army fell to Vendôme's brother Saint-Pol with the force being subject to another attack on 30 April in which Bayard was shot by an arquebus. The campaign now entered France, with the connétable de Bourbon invading Provence.[136] The army of Bonnivet re-entered the kingdom in June 1524.[137]

Return to the trust of the king

[edit]In November, a false rumour spread that the comte de Saint-Pol had fled to join with Bourbon in rebellion, and that the king had responded by detaining Vendôme.[125] Vendôme for his part had returned to active command in Picardie by this month, with a new deputy governor, the Picard noble the sieur de Pont-Rémy.[120]

In January 1524, Vendôme received the petition of Péronne to be exempted from the taille. He secured for them a five year exemption beginning in the April of that year. This was extended to a ten year exemption when the mayor visited the court in 1526, and with Vendôme's support got it expanded.[138] His ability to represent Péronne in this matter was augmented by his nominal leadership position over the royal council that he gained in 1525.[84]

The king held a lit de justice (a special session of the parlement under the presidency of the king) on 7 March 1524 at the parlement. Many pairs were present for the occasion, including the duc de Vendôme, the duc d'Alençon, the bishop of Langres and the bishop of Noyon. Also present were the sénéchal de Normandie, and the vicomte de Thouars. In this session, the duc de Bourbon was accused of rebellion, desertion and lèse majesté. His arrest was ordered, the sentence declared to be death and all his lands declared to be defaulted to the king.[139]

Anxious concerning the troubles of his army in Italy, on 10 March François ordered a procession be conducted for the following day, so that god might grant his soldiers victory. He participated in this procession in the capital, alongside Vendôme, Alençon, the duc de Longueville, the vicomte de Thouars, the Grand Maître and all the various parlementaires.[140]

An army under the connétable de Bourbon invaded Provence in the summer of 1524. Aix fell to his army on 8 August. He then settled in for a siege of Marseille, hoping it would serve as a bridgehead into the kingdom. With supplies poor, and a royal army being assembled near Avignon this siege did not progress well, and he was soon forced back out of Provence, with the maréchal de Montmorency on his heels.[136]

With the driving out of the Imperials from Provence, François prepared to lead the fight back into Italy. At Pignerol on the border from 15 to 17 October 1524 he ratified his designation of Louise as regent of the kingdom with the rights she had enjoyed in 1515. Only a few captains who had distinguished themselves for their loyalty during the affair of Bourbon's treason would be left to protect the kingdom in the king's absence: Vendôme for Picardie and the Île de France; the comte de Guise, and comte de Vaudémont for Champagne and Bourgogne; the comte de Maulévrier in Normandie; the comte de Laval in Bretagne; and the seigneur de Lesparre for Languedoc and Guyenne. Even as he was putting his affairs in order before his departure, the vanguard of the French army was already menacing Milan.[141]

Starting in September, Vendôme was entrusted with the defence of Picardie while the king was on campaign.[142] He thus spent the next few months in Picardie, tending to the defence of the province.[143][119] Vendôme split responsibility for the province with his deputy Pont-Rémy. The former based himself out of La Fère while the latter kept maritime Picardie under a watchful eye.[120]

Kingdom in crisis

[edit]Pavia

[edit]

The duc de Vendôme complained to the regent Louise in a letter of 30 January 1525 that he had only received 18,000 livres for the pay of his infantry and light horse. He highlighted to the regent that this money would last only a month and cause desertions from garrisons.[144]

As the Imperials abandoned Milan, François was able to enter the city without a fight. The king resolved to lay siege to Pavia, a well fortified town. The bombardment of the place began on 6 November.[145] Come January 1525, the Imperial commanders were in a situation where they needed a quick victory lest they face the dissolution of their soldiers due to lack of pay.[146] On 24 February the French were drawn into a catastrophic battle outside the city.[147] The battle constituted the most thorough destruction of the French nobility since Azincourt over a century earlier. Of the 1,400 men-at-arms present, only 400 escaped the carnage. 1,200 Frenchmen were killed, and a further 10,000 taken as prisoners, among them the king and Vendôme's brother the comte de Saint-Pol (though the latter would escape in May).[148]

The disastrous battle of Pavia arrived at a poor time, coinciding as it did with the death of Vendôme's deputy, Pont-Rémy in a minor battle around Hesdin in February 1525.[149] Word reached Vendôme of what had transpired in Pavia on 7 March.[149] The prince replaced Pont-Rémy in his captaincy of Montreuil with his brother the seigneur de Bernieulles.[81]

Louise forms council

[edit]With François in captivity, Louise became responsible for the French kingdoms very survival.[150] On 3 March she wrote to the king's various councillors, urging them to do all they were able to do for the preservation of the kingdom. She chiefly looked to her old faithfuls: the sécretaire d'État (secretary of state) Florimond Ier Robertet and chancellor Duprat but she was wise enough in the circumstances to expand her council.[151] In the absence of the premier prince du sang, the duc d'Alençon, the duc de Vendôme was summoned to council in the city, alongside his brother the cardinal de Bourbon, the vicomte de Lautrec (governor of Guyenne), the comte de Guise (governor of Champagne) and the seigneur de Lesparre (brother of Lautrec).[152] Jean de Selve was brought over from the parlement, and before his departure to Lyon, he urged the body to moderate its criticism of royal policy. This would be for nought.[87] The support of Vendôme and Lautrec was particularly sought for securing the queen mothers base.[153] According to the memoires of the du Bellay brothers, around this time a coalition tried to encourage Vendôme to usurp the position of Louise and take the regency for himself. He refused to take this step but according to the memoires of du Bellay 'dipped his foot in the water'. Recognising the threat he represented for what it was, Louise moved to sate him with the honorary position of head of the royal council.[154] Thus, the duc de Vendôme presided over royal council.[1]

In addition to the above grandees in the council, men of the church and robe were summoned to Lyon. The first priority of the regent and her council were to prevent an invasion of the kingdom, clamp down on any possible disorders, and fill all the offices vacated by the slaughter of the gendarmerie at Pavia.[152]

Though he was head of the royal council, ambassadorial reports of the time suggested he remained politically insubstantial. He would have to navigate and secure the approval of a large council comprising twenty four persons, without whom he was powerless.[155] It was Lautrec and Duprat who held the real power.[156] Vellet gives an example of this in the arrival of the English agent Casale at the French court on 28 September 1525, in the wake of the Treaty of the More, which had been signed on 30 August.[156] Casale informed Louise that his master, Henry VIII remained true to France even though he was receiving the entreaties of the Imperial party directed towards his favourite the cardinal Wolsey. She told Casale that she would discuss all he had said with Duprat and Lautrec.[157]

Northern defence

[edit]On 7 March, Louise authorised the parlement of Paris to take the necessary security measures to assure itself of the capital. Collaborating with the municipal government of the city it was agreed to close most of the gates of the city, prohibit the passage of the Seine at night with goods and a new council was established, not only to manage affairs in Paris but also more distant cities in the north. There would be thirty five meetings of this council prior to July.[143]

Vendôme passed through Paris on his way to Lyon on 10 March. He urged the city to show itself well as an example to the rest of the kingdom during this time of crisis. Around the city, bands of soldiers were engaging in pillage at this time.[158] Along with many of the other advisors he urged deference to the parlement of Paris.[151] He would go as far as to criticise the king's advisors and reaffirming his desire to follow the lead of the parlement while he was in the city on 10 March.[159] As for the parlement, it followed its traditional approach during crises in the kingdom, looking to strengthen its own position.[160]

On 26 March, absent from his governate while he was on the council in Lyon, the comte de Brienne was dispatched as Vendôme's lieutenant to deal with the problems of pillaging soldiers.[158] He would arrive to assume his charge in April, and would be the sole authority in the province until the prince's return in 1527. This appointment came at the demand of the parlement who were insistent on the need for a competent man to be in the province during his absence. Nevertheless, the comte de Brienne was a man of his own choosing, and a (Luxembourg) kinsmen. Along with Brienne, Vendôme sent the lieutenant of his compagnie d'ordonnance the sieur de Torcy.[161] Vendôme would remain in Lyon until such time as François was released from captivity.[162]

The parlement resolved to raise 200 lances in Picardie with an intended date of muster of 8 May, and Vendôme declared that these new lances would be paid by revenue from the taille collected in April. These taille funds did not appear in Picardie. As a result of this the trésoriers had to raise the money via alternate means.[163]

National defence

[edit]The elements of the gendarmerie that had not accompanied the king over the Alps were assembled. Alençon, who had survived the slaughter at Pavia, then returned with what was left of the army of Italy in a pitiful state. A few thousand men were allocated to the maréchal de Lautrec to hold the line at the Alps. Other sensitive areas (Bourgogne, Champagne, Picardie, Lyon) were bolstered. The latter became the most defended city in the kingdom.[162] Elsewhere on the frontier local initiative was looked to.[152] Alençon himself would die of illness on 11 April, thereby making Vendôme the premier prince du sang.[164][165] Much to the considerable fury of Vendôme, Duprat and Louise had convinced the childless prince to establish as his heir, the king's second son, the duc d'Orléans, rather than his sister, to whom Vendôme was married. Though his brother, Saint-Pol had escaped from his captivity after Pavia, he was too wounded to support Vendôme in this dispute, leaving the prince powerless to impose himself.[166]

Vendôme requested Andrea Doria, the général du galères du roi (general of the king's galleys) and La Fayette the vice-amiral (vice-admiral) to facilitate the return of the army of the duke of Albany which was in the Papal States. This force would then reinforce the domestic French forces.[162] Albany would thus join the band of Vendôme, Lautrec and Guise as a principal defender of the kingdom.[164]

The poverty of the state forced efficiencies. The compagnies of French captains were reduced in size, sometimes by up to a third. Concurrently ransom money was advanced to free captives in Italy.[162]

In May, bands of Lutheran peasants from the Empire invaded Bourgogne, imagining they would find a kingdom in total chaos. They were brutally crushed by the duc de Lorraine, the comte de Guise and the comte de Vaudémont.[162]

Duprat and Louise against the parlement

[edit]

Vendôme's professed position of deference to the parlement worked well with that of many conseillers of the Paris parlement, who were hostile to Louise and the chancellor Duprat. The parlement was particularly hostile to a matter close to Louise's heart, the Concordat of Bologna by which the king had gained the right to designate the holders of bishoprics and abbeys, suppressing the prior system of elections. François' captivity had opened the door to openly oppose nominations, such as that of Duprat as archbishop of Sens and abbot of Saint-Benôit-sur-Loire in February 1525. According to the memoires of Martin du Bellay, several parlementaires sought for Vendôme to assume a position of pre-eminence over them. By this means the parlement hoped to take advantage of divisions in the state to limit royal power and accentuate their own.[159][149]

In April, the parlement submitted remonstrances to the crown on a range of policies, from the tolerance of heretics, to assaults against Gallican liberties (autonomy of the French church), fiscal abuses and circumvention of the proper process of justice. These critiques were accepted in good humour by Louise, but she subsequently paid them no mind.[167]

On 5 September 1525, the parlement declared the assumption of an abbey, by another candidate of Louise, a certain Chantereau, null and void. He was prohibited from collecting the income of the abbey. This was to overturn the judgement of the Grand Conseil which had decided in Chantereau's favour in assuming the charge. That same day, the parlementaires decided to write to Vendôme, Saint-Pol, the cardinal de Bourbon and vicomte de Lautrec hoping that these men were hostile to Duprat and the enterprises of the Grand Conseil (over which Duprat was judge). The letters to these men would be issued on 12 September[168]. Duprat's 'machinations' were put in opposition to the interests of François, Louise, and justice. In addition to this appeal the parlement summoned a meeting of the pairs de France for 12 November so that they discuss matters as related to the king, the authority of the parlement and justice.[154] The true intention of this proposed meeting would be to attack Duprat.[169] However, the parlement were hesitant to follow through with this threat, and postponed the summons until they had received a response from Louise's council.[170]

Though stalling the summoning of the pairs, the parlement requested Vendôme and the cardinal de Bourbon present their remonstrances to Louise. Both men were invited to sit in the parlement. On 12 September, the parlement wrote to Louise complaining that the independence of justice was threatened by enterprises of 'certain individuals' in the name of the Grand Conseil (i.e. Duprat). Louise remained firm in her faith in Duprat, and was wary of Vendôme who the body was pushing forward.[170]

The appeals of the parlement to the various members of the court (among them Vendôme) fell on deaf ears. Louise was increasingly confident in her position after reaching accord with England. She kept the three parlementaires who had come to meet with her waiting for six weeks then berated them for their own abuses of justice. She further accused them of trying to call an Estates General on their own authority. On 14 November, one of the parlementaires announced to the parlement in Paris that the government was liable to soon arrest some of its members.[169] The parlement therefore opted to suspend its action against the disputed sees in return for the Grand Conseil likewise suspending its actions. Their wish to have Duprat before them was explained away as intended to produce 'brotherly and good discussions'. Louise was satisfied in this, knowing François upon his return would subdue the body.[171]

Vendôme against Lautrec

[edit]According to a certain account, Louise made out that she wanted to establish the vicomte de Lautrec as lieutenant-général over Vendôme, hoping by this means to make clear to Vendôme what he had to lose if he joined the parlementaires party of opposition. Vendôme and Lautrec had been in a rivalry for pre-eminence in the kingdom. While Vendôme had greater legitimacy, he was poorer in military experience than Lautrec, allowing the latter to better pose as the kingdoms saviour at a time when the borders were vulnerable.[172] Thus, Louise could set up Lautrec in opposition to him.[173] According to an English informant, there was tension between the two men during May.[142] During June, Vendôme and Lautrec entered a dispute with one another, during their argument Louise and Duprat took the side of Lautrec, while Vendôme enjoyed the support of Robertet.[166] Champollion-Figeac dates the document concerning the plan to appoint Lautrec lieutenant-général in Vendôme's stead to around October 1525, Michon disputes this however, arguing that from what it says about Saint-Pol elsewhere that it can be placed in May or June.[155][170]

Through her manoeuvrers, Louise was able to quickly defuse the opposition alliance of the princes du sang and parlementaires.[170]

The parlement for its part had been less interested in stoking the fires of hatred between Vendôme and Lautrec than in isolating and attack Duprat.[174][168]

Accord with England

[edit]Negotiations for peace with England took place in the summer of 1525. Finally, on 30 August, at the English palace of The More, a treaty was agreed. By its terms, hostilities between England and France would cease. A defensive league was to be established including the participation of England, France, Hungary, Navarre, Scotland, the Papacy, the duc de Lorraine and others. Between England and France there would be free movement of peoples and goods. Henry VIII would release his French hostages that were held as security for the French payment of Tournai (which had been sold to the French in 1518). The English king would renounce all his rights in France, and assist in the securing of François' release for 'reasonable terms'. The French for their part, would give the English 2,000,000 écus in the form of 100,000 écus annuities paid every year in two instalments, May and November. The pensions the French crown had provided to English princes would be restored.[175] In the absence of François, to ensure the French abiding by this treaty, Louise and, the king's eldest son the duc de Bretagne would be obliged to appear before an ecclesiastical tribunal to request excommunication should they fail to uphold the terms.[176] The French debt to the English was pledged against eight bonnes villes of France, and nine nobles (among whom were the maréchal de Montmorency, the vicomte de Lautrec, the seigneur de Brienne, the duc de Longueville and the duc de Vendôme and his two brothers). François would have to validate the peace within three months, by letter if still in Imperial captivity.[177]

The peace was published in France on 22 September and on 27 September a text for the subjects of the French crown was distributed. It failed to mention the sums the government had paid to ensure tranquillity on the borders. Vendôme and the other nobles kept quiet about the obligations the peace imposed on them. The parlement would register the peace on 20 October, to be followed by the reticent city of Paris a few weeks later.[177]

Towards the release of François

[edit]When the regent Louise learned of the transfer of her son from Italy to Spain, the chancellor Duprat and Vendôme designated the parlementaire de Selve to begin to undertake negotiations with the Imperial party.[178]

In October, Vendôme was appraised of the ill health of the king, who was still in captivity in Madrid.[179] There were some fears that the king would die from his illness.[180]