Chaozhu

| Chaozhu | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Chinese | 朝珠 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | Court beads | ||||||

| |||||||

| English name | |||||||

| English | Mandarin necklace/ Court necklace | ||||||

Chaozhu (Chinese: 朝珠; pinyin: Cháozhū), also known as Court necklace and Mandarin necklaces in English,[1] is a type of necklace worn as an essential element of the Qing dynasty Court clothing uniform (mostly worn in the formal and semi-formal court attire).[2][1] Chaozhu were worn by the Qing dynasty Emperors and members of the Imperial family,[3] by imperial civil officials from the 1st to the 5th rank and the military official above the 4th rank.[1][4]: 52

They were worn by men and women; men wore one chaozhu and only women of high-ranking status were allowed to wear triple chaozhu (one at the neck and two diagonally over each shoulder and underarms).[1][4]: 52 The chaozhu was used an indicator of social ranking[1] and seasons;[2] they were also practical as it could be used for mathematical calculations in the absence of an abacus.[3]

Chaozu originated from a Buddhist rosary sent in 1643 by the Dalai Lama to Emperor Shunzhi;[3] it was then redesigned by the Manchu to include new elements.[1] The chaozu is based on the 108-beaded Buddhist rosary;[4]: 52 it however shifted from being a religious object to being a symbol of social status while only maintaining some liturgic function.[1] The chaozhu is composed of flat cords, long string of beads various materials (wood, precious stones, and sometimes pearls and glass) and pendants or filigree which could also be made of precious stones or precious metal.[1][2][5][6]

Design and construction

[edit]The materials and arrangements of the chaozhu was strictly regulated and codified in the Qing Huidian Tukao (written in the early Qing dynasty) and in the Huangchao Liqi Tushi (Chinese: 皇朝禮器圖式; lit. 'Illustrations of Imperial Ritual Paraphernalia', which was composed in 1767 AD during the reign of Emperor Qianlong).[2][1] The Qing dynasty regulated the materials used for each court rank,[1] including types of precious stones and the colour of the silk tapes and cords.[4]: 52 [1]

Men wore one chaozhu and only women of high-ranking status were allowed to wear triple chaozhu (one at the neck and two diagonally over each shoulder and underarms).[1][4]: 52 In arrangement, women's chaozhu differed slightly from the men's: men had a single shuzhu at the right and the pair shuzhu is found on the left (at his heart) while women the single shuzhu at the left and the pair at the right.[1]

-

Chaozhu worn around the neck of an Emperor

-

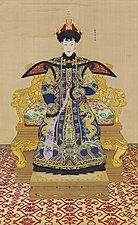

Chaozhu worn by an Empress Dowager

-

Triple chaozhu worn by an Imperial Noble Consort.

-

Chaozhu worn a courtier

-

Chaozhu worn by an official

Arrangement

[edit]The arrangement of chaozhu is related to the Buddhist rosary.[2] The chaozhu is composed of 108 small beads, with 4 large beads of contrasting stones to symbolize the 4 seasons and was placed between groups of 27 beads.[3][4]: 52 The topmost divider is called fotou (lit. "Buddha's Head").[5] There is also a long pendant hanging at the back which acts as a large counterbalance to keep the necklace in place called beiyun (lit. "back cloud");[4]: 52 the beiyun is composed of a flat cord which could be connected to other precious stones beads and pendants and/or filigree.[5][6] There is also 3 small dangling counterbalances which is attached to the necklace called shuzhu (i.e. 'counting strings') with each containing 8 memory beads (jinian er).[4]: 52 The three smaller counterbalances complements the beiyun; it is also composed of precious stones beads and pendants and/or filigree.[5][6]

-

Chaozhu, Court necklace, Qing dynasty

-

Chaozhu, Court necklace, Qing dynasty.

-

Chaozhu, 1700s or 1800s AD.

Materials

[edit]Materials which could be used to make the necklace could include: Eastern pearls (i.e. fresh water pearls, which are produced in the lower reaches of northeastern Songhua River and its tributaries; these pearls were also treasured in the Northern Song dynasty according to the sixth juan of the Collected Discourses of Mount Tiewei,《鐵圍山叢談 -Tiewei shan congtan》), red corals, lapis lazuli, turquoise, ruby,[5] amber (yellow or red), jadeite (including yupei and beads),[2][6][1] and precious metals such as gold filigree.[5] Commonly glass beads were actually used to imitate precious stones, such jade, amber, and precious coral, in many chaozhu despite the regulations for each ranks were regulated.[4]: 52 Wooden beads and beads made out of seeds (e.g. apricots, peaches, and plums) could also be used.[1]

Based on the Qing dynasty court dress regulations, certain materials were prohibited based on the court ranking of its wearer.[1] For example, only the emperor, empress dowager, and empress were allowed to wear adornments with Eastern pearls during certain palace ceremonies.[5] Princes, members of the nobility, and ministers were forbidden from wearing pearls casually.[5]

The colour of the silk cords were regulated: bright yellow (明黄, i.e. imperial yellow) for the Emperor and the Crown prince, gold yellow (金黄) for the princes, and blue (石青) by lords and by the state officials (minggong).[1]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Heroldová, Helena (2019-11-01). "Court Beads: Manchu Rank Symbols in the Náprstek Museum". Annals of the Náprstek Museum. 40 (2): 95–106. doi:10.2478/anpm-2019-0017. ISSN 2533-5685.

- ^ a b c d e f "Qing court necklace with beads". www.roots.gov.sg. 2021. Retrieved 2022-03-13.

- ^ a b c d Garrett, Valery M. (2007). Chinese dress : from the Qing Dynasty to the Present. Tokyo: Tuttle Pub. ISBN 978-0-8048-3663-0. OCLC 154701513.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Vollmer, John E. (2007). Dressed to rule : 18th century court attire in the Mactaggart Art Collection. Mactaggart Art Collection. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press. ISBN 978-1-55195-705-0. OCLC 680510577.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Eastern Pearl Court Beads|The Palace Museum". The Palace Museum. Retrieved 2022-03-13.

- ^ a b c d "Court beads (Chaozhu) from the 18th century". collection.maas.museum. Retrieved 2022-03-13.