Yuen Ren Chao

Yuen Ren Chao | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

趙元任 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

c. 1916 portrait of Chao | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 3 November 1892 Tianjin, Qing dynasty | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 25 February 1982 (aged 89) Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Citizenship |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Education | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Known for | Chinese language reform | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Works |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Scientific career | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fields | Dialectology, phonology | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Institutions | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Notable students | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 趙元任 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 赵元任 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Yuen Ren Chao (3 November 1892 – 25 February 1982), also known as Zhao Yuanren, was a Chinese-American linguist, educator, scholar, poet, and composer, who contributed to the modern study of Chinese phonology and grammar. Chao was born and raised in China, then attended university in the United States, where he earned degrees from Cornell University and Harvard University. A naturally gifted polyglot and linguist, his Mandarin Primer was one of the most widely used Mandarin Chinese textbooks in the 20th century. He invented the Gwoyeu Romatzyh romanization scheme, which, unlike pinyin and other romanization systems, transcribes Mandarin Chinese pronunciation without diacritics or numbers to indicate tones.

Early life and education

[edit]Chao was born in Tianjin in 1892, though his family's ancestral home was in Changzhou, Jiangsu. In 1910, Chao went to the United States with a Boxer Indemnity Scholarship to study mathematics and physics at Cornell University, where he was a classmate and lifelong friend of Hu Shih (1891–1962), the leader of the New Culture Movement. He then became interested in philosophy; in 1918, he earned a PhD in philosophy from Harvard University with a dissertation entitled "Continuity: Study in Methodology".[1]

Already in college his interests had turned to music and languages. He spoke German and French fluently and some Japanese, and he had a reading knowledge of Ancient Greek and Latin. He was Bertrand Russell's interpreter during Russell's visit to China in 1920. In My Linguistic Autobiography, Chao wrote of his ability to pick up a Chinese dialect quickly, without much effort. Chao possessed a natural gift for hearing fine distinctions in pronunciation that was said to be "legendary for its acuity",[2] enabling him to record the sounds of various dialects with a high degree of accuracy.

Career development

[edit]In 1920, Chao returned to China and taught mathematics at Tsinghua University. The next year, he returned to the United States to teach at Harvard University. In 1925, he again returned to China, teaching at Tsinghua, and in 1926 began a survey of the Wu dialects.[3] While at Tsinghua, Chao was considered one of the 'Four Great Teachers / Masters' of China, alongside Wang Guowei, Liang Qichao, and Chen Yinke.

He began to conduct linguistic fieldwork throughout China for the Institute of History and Philology of Academia Sinica from 1928 onwards. During this period of time, he collaborated with Luo Changpei, another leading Chinese linguist of his generation, to translate Bernhard Karlgren's Études sur la Phonologie Chinoise (published in 1940) into Chinese.

In 1938, he left for the US and resided there afterwards. In 1945, he served as president of the Linguistic Society of America, and in 1966 a special issue of the society's journal Language was dedicated to him. In 1954, he became an American citizen. In the 1950s he was among the first members of the Society for General Systems Research. From 1947 to 1960, he taught at the University of California at Berkeley, where in 1952, he became Agassiz Professor of Oriental Languages.

Work

[edit]

While in the United States in 1921, Chao recorded Standard Chinese pronunciation gramophone records, which were then distributed nationally, as proposed by Commission on the Unification of Pronunciation.

He is the author of one of the most important standard modern works on Chinese grammar, A Grammar of Spoken Chinese, which was translated into Chinese separately by Lü Shuxiang in 1979 and by Ting Pang-hsin in 1980. It was an expansion of the grammar chapters in his earlier textbooks, Mandarin Primer and Cantonese Primer. He was co-author of the Concise Dictionary of Spoken Chinese, which was the first dictionary to characterize Chinese characters as bound or free—usable only in polysyllables or permissible as a monosyllabic word, respectively.

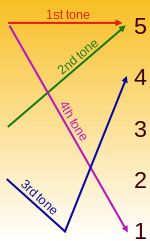

Chao invented the General Chinese phonetic system to represent the pronunciations of all major varieties of Chinese simultaneously. It is not specifically a romanization system, but two alternate systems: one uses Chinese characters phonetically as a syllabary, and the other is an alphabetic romanization system with similar sound values and tone spellings to Gwoyeu Romatzyh. On 26 September 1928, Gwoyeu Romatzyh was officially adopted by the Republic of China—led at the time by the Kuomintang (KMT).[4][5] The corresponding entry in Chao's diary, written in GR, reads G.R. yii yu jeou yueh 26 ry gong buh le. Hoo-ray!!! ("G.R. was officially announced on September 26. Hooray!!!")[6] Chao also contributed Chao tone letters to the International Phonetic Alphabet.

His translation of Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, where he tried his best to preserve all the word plays of the original, is considered "a classical piece of verbal art."[7]

Chao also wrote "Lion-Eating Poet in the Stone Den", a Chinese text consisting of 92 characters, each with the syllable shi in modern Standard Chinese, only varying by tone. When written out using Chinese characters the text can be understood, but it is incomprehensible when read out aloud in Standard Chinese, and therefore also incomprehensible on paper when written in romanized form. This example is often used as an argument against the romanization of Chinese. In fact, the text was an argument against the romanization of Classical Chinese: Chao was actually a proponent for the romanization of written vernacular Chinese.

His composition "How could I help thinking of her" was a pop hit during the 1930s in China; its lyrics were penned by fellow linguist Liu Bannong.

Chao translated Jabberwocky into Chinese[8] by inventing characters to imitate what Rob Gifford describes as the "slithy toves that gyred and gimbled in the wabe of Carroll's original".[9]

Family and later life

[edit]

In 1920, he married the physician Yang Buwei.[10] The ceremony was simple, as opposed to traditional weddings, attended only by Hu Shih and one other friend. Hu's account of it in the newspapers made the couple a model of modern marriage for China's New Culture generation.[11]

Yang Buwei published How to Cook and Eat in Chinese in 1946, and the book went through many editions. Their daughter Rulan wrote the English text and Mr. Chao developmentally edited the text based on Mrs. Chao's developed recipes, as well as her experiences gathering recipes in various areas of China. Among the three of them, they coined the terms "pot sticker" and "stir fry" for the book, terms which are now widely accepted, and the recipes popularized various related techniques.[12] His presentation of his wife's recipe for "Stirred Eggs" is a classic of American comic writing.

Both Chao and his wife Yang were known for their good senses of humor, he particularly for his love of subtle jokes and language puns: they published a family history entitled, Life with Chaos: the autobiography of a Chinese family. Their first daughter Rulan Chao Pian (1922–2013) was Professor of East Asian Studies and Music at Harvard. Their second daughter Nova Chao (1923–2020) was a Harvard-trained chemist, professor at Central South University and member of the Chinese Academy of Engineering. Their third daughter Lensey was born in 1929; she is a children's book author and mathematician.

Late in his life, Chao was invited by Deng Xiaoping to return to China in 1981. Previously at the invitation of Premier Zhou Enlai, he and his wife returned to China in 1973 for the first time since the 1940s. After his wife died in March 1981 he visited China again between May and June. He died in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Selected bibliography

[edit]- "A system of 'tone-letters'", Le Maître Phonétique, 3, vol. 8, no. 45, pp. 24–27, 1930, JSTOR 44704341

- "The Non-uniqueness of Phonemic Solutions of Phonetic Systems" (PDF), Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philology, vol. 4, no. 4, Academia Sinica, pp. 363–398, 1934

- Karlgren, Bernhard; Chao, Yuen Ren; Li, Fang-Kuei; Luo, Changpei (1940), 中国音韵学研究 [Study on Chinese Phonology], The Commercial Press

- Chao, Yuen Ren; Yang, Lien-sheng (1947), Concise Dictionary of Spoken Chinese, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

- Cantonese Primer, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1947

- Mandarin Primer, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1948

- Grammar of Spoken Chinese, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1965

- Cantonese Primer, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1947

- "What Is Correct Chinese?", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 81 (3): 171–177, 1961, doi:10.2307/595651, JSTOR 595651

- Language and symbolic systems, Cambridge University Press, 1968, ISBN 978-0-521-04616-9

- Chao, Yuen Ren (1976), Aspects of Chinese Sociolinguistics: Essays, Stanford University Press, ISBN 978-0-8047-0909-5

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Boorman (1967), pp. 148–149.

- ^ Coblin (2003), p. 344.

- ^ Malmqvist (2010), p. 302.

- ^ Kratochvíl (1968), p. 169.

- ^ Xing & Feng (2016), pp. 99–111.

- ^ Zhong (2019), p. 41.

- ^ Feng 2009, pp. 237–251.

- ^ Chao (1969), pp. 109–130.

- ^ Gifford (2007), p. 237.

- ^ Chao et al. (1974), p. 17.

- ^ Feng (2011).

- ^ Epstein (2004).

Works cited

[edit]- Boorman, Howard Lyon (1967), Biographical dictionary of republican China, New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-08955-5

- Chao, Yuen Ren (1969), "Dimensions of Fidelity in Translation With Special Reference to Chinese", Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, 29, Harvard-Yenching Institute: 109–130, doi:10.2307/2718830, JSTOR 2718830

- ———; Levenson, Rosemary; Schneider, Laurence A.; Haas, Mary Rosamond (1974), Chinese linguist, phonologist, composer and author (Transcript), pp. 177–178

- Coblin, W. South (2003), "Robert Morrison and the Phonology of Mid-Qing Mandarin", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 13 (3): 339–355, doi:10.1017/S1356186303003134, S2CID 162258379

- Epstein, Jason (13 June 2004), "Food: Chinese Characters", The New York Times, retrieved 31 July 2013

- Feng, Jin (2011), "With this Lingo, I Thee Wed: Language and Marriage in Autobiography of A Chinese Woman", Journal of American-East Asian Relations, 18 (3–4): 235–247, doi:10.1163/187656111X610719

- Feng, Zongxin (2009), "Translation and reconstruction of a wonderland: Alice's Adventures in China", Neohelicon, 36 (1): 237–251, doi:10.1007/s11059-009-1020-2

- Gifford, Rob (2007), China Road: A Journey into the Future of a Rising Power, New York: Random House, ISBN 978-1-400-06467-0

- Kratochvíl, Paul (1968), The Chinese Language Today, Hutchinson, ISBN 0-090-84651-6

- Malmqvist, N. G. D. (2010), Bernhard Karlgren: Portrait of a Scholar, Rowman & Littlefield, p. 302, ISBN 978-1-61146-001-8

- Xing, Huang; Feng, Xu (2016), "The Romanization of Chinese Language", Review of Asian and Pacific Studies, vol. 41, pp. 99–111, doi:10.15018/00001134, hdl:10928/892, ISSN 0913-8439

- Zhong, Yurou (2019), Chinese Grammatology: Script Revolution and Literary Modernity, 1916–1958, Columbia University Press, p. 41, doi:10.7312/zhon19262, ISBN 978-0-231-54989-9

Further reading

[edit]- Wang, William S-Y. (1983), "Yuen Ren Chao", Language, 59 (3): 605–607, JSTOR 413906

- LaPolla, Randy (2017), "Chao, Y.R. [Zhào Yuánrèn] 趙元任 (1892–1982)", in Sybesma, Rint (ed.), Encyclopedia of Chinese Language and Linguistics (PDF), vol. A–Dǎi, Brill, pp. 352–356, doi:10.1163/2210-7363_ecll_COM_000028

External links

[edit]- (in Chinese) Chao's gallery, with related essays, at Tsinghua's site

- Yuen Ren Chao student notes of lectures given by George Sarton, 1916-1918, Niels Bohr Library & Archives

- 1892 births

- 1982 deaths

- Chinese male composers

- Chinese emigrants to the United States

- Linguists from China

- American writers of Chinese descent

- English–Chinese translators

- Chinese–English translators

- Chinese male non-fiction writers

- Cornell University alumni

- Phonologists from China

- Chinese sinologists

- University of California, Berkeley College of Letters and Science faculty

- Academic staff of Tsinghua University

- Harvard University faculty

- Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences alumni

- Cornell University faculty

- Academic staff of the National Southwestern Associated University

- Boxer Indemnity Scholarship recipients

- Members of Academia Sinica

- Writers from Tianjin

- Educators from Tianjin

- Musicians from Tianjin

- 20th-century Chinese musicians

- Scientists from Tianjin

- 20th-century Chinese translators

- Chinese composers

- 20th-century composers

- Linguistic Society of America presidents

- Linguists of Chinese

- 20th-century linguists

- Corresponding fellows of the British Academy

- 20th-century male musicians

- Chinese language reform