Chamar

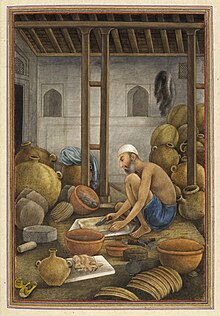

Leather-bottle makers (Presumably members of the 'Chamaar' caste), Tashrih al-aqvam (1825) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| India • Pakistan | |

| Languages | |

| Hindi • Punjabi | |

| Religion | |

| Hinduism • Islam • Sikhism • Ravidassia religion • Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Jatav • Ramdasia • Ravidassia • Raigar[1] • Chambhar • Dhusia • Madiga • Ad-Dharmi • Ahirwar |

Chamar (or Jatav)[2] is a community classified as a Scheduled Caste under modern India's system of affirmative action that originated from the group of trade persons who were involved in leather tanning and shoemaking.[3] They are found throughout the Indian subcontinent, mainly in the northern states of India and in Pakistan and Nepal.

History

The Chamars are traditionally associated with leather work.[4] Ramnarayan Rawat posits that the association of the Chamar community with a traditional occupation of tanning was constructed, and that the Chamars were instead historically agriculturists.[5]

The term chamar is used as a pejorative word for dalits in general.[6][7] It has been described as a casteist slur by the Supreme Court of India and the use of the term to address a person as a violation of the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989.[8]

Movement for upward social mobility

Between the 1830s and the 1950s, the Chamars in the United Provinces, especially in the Kanpur area, became prosperous as a result of their involvement in the British leather trade.[9]

By the late 19th century, the Chamars began rewriting their caste histories, claiming Kshatriya descent.[10] For example, around 1910, U.B.S. Raghuvanshi published Shri Chanvar Purana from Kanpur, claiming that the Chamars were originally a community of Kshatriya rulers. He claimed to have obtained this information from Chanvar Purana, an ancient Sanskrit-language text purportedly discovered by a sage in a Himalayan cave. According to Raghuvanshi's narrative, the god Vishnu once appeared in form of a Shudra before the community's ancient king Chamunda Rai. The king chastised Vishnu for reciting the Vedas, an act forbidden for a Shudra. The god then revealed his true self, and cursed his lineage to become Chamars, who would be lower in status than the Shudras. When the king apologized, the god declared that the Chamars will get an opportunity to rise again in the Kaliyuga after the appearance of a new sage (whom Raghuvanshi identifies as Ravidas).[11]

A section of Chamars claimed Kshatriya status as Jatavs, tracing their lineage to Krishna, and thus, associating them with the Yadavs. Jatav Veer Mahasabha, an association of Jatav men founded in 1917, published multiple pamphlets making such claims in the first half of the 20th century.[12] The association discriminated against lower-status Chamars, such as the "Guliyas", who did not claim Kshatriya status.[13]

In the first half of the early 20th century, the most influential Chamar leader was Swami Achutanand, who founded the anti-Brahmanical Adi Hindu movement, and portrayed the lower castes as the original inhabitants of India, who had been enslaved by Aryan invaders.[14][15]

Political rise

In the 1940s, the Indian National Congress promoted the Chamar politician Jagjivan Ram to counteract the influence of B.R. Ambedkar; however, he remained an aberration in a party dominated by the upper castes.[16] In the second half of the 20th century, the Ambedkarite Republican Party of India (RPI) in Uttar Pradesh remained dominated by Chamars/Jatavs, despite attempts by leaders such as B.P. Maurya to expand its base.[17]

After the decline of the RPI in the 1970s, the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) attracted Chamar voter base. It experienced electoral success under the leadership of the Chamar leaders Kanshi Ram and Mayawati; Mayawati who eventually became the Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh.[18] Other Dalit communities, such as Bhangis, complained of Chamar monopolisation of state benefits such as reservation.[19] Several other Dalit castes, resenting the domination of Dalit politics by Chamars/Jatavs, came under the influence of the Sangh Parivar.[20]

Nevertheless, with the rise of BSP in Uttar Pradesh, a collective solidarity and uniform Dalit identity was framed, which led to coming together of various antagonistic Dalit communities. In the past, Chamar had shared bitter relationship with the Pasis, another Dalit caste. The root cause of this bitter relationship was their roles in feudal society. The Pasis worked as lathail or stick wielders for the "Upper Caste" landlords and the later had compelled them in past to beat Chamars many a times. Under the unification drive of BSP, these rival castes came together for the cause of unity of Dalits under same political umbrella.[21]

Social exploitation

In reference to villages of Rohtas and Bhojpur district of Bihar, prevalence of a practice was revealed, in which it was obligatory for the women of Chamar, Musahar and Dusadh community to have sexual contacts with their Rajput landlords. In order to keep their men in submissive position, these upper-caste landlords raped these Dalit women, and often implicate the male members of latter's family in false cases, when they refused sexual contacts with them. The other form of oppression which was inflicted on them was disallowing them to walk on the pathways and draw water from the wells, which belonged to Rajputs. The "pinching of breast" by the upper caste landlords and the undignified teasings were also common form of oppression. In the 1970s, the activism of peasant organizations like "Kisan Samiti" is said to have brought an end to these practices and subsequently the dignity was restored to the women of lower castes. The oppression however was not fully stopped as the friction between upper-caste landlords and the tillers continued. There are reports which indicates that the upper-caste landlords often took the help of Police in order to beat the women of Chamar caste and draw them out of their villages on the question of parity in wages.[22][23][24]

Chamar Caste in different States of India

Ad-Dharmi

The Ad-Dharmi is a Chamar caste sect in the state of Punjab, in India and is an alternative term for the Ravidasia religion, meaning Primal Spiritual Path.[25][26][27] The term Ad-Dharm came into popular usage in the early part of the 20th century, when many followers of Guru Ravidas converted to Sikhism and were severely discriminated against due to their low caste status (even though the Sikh religion is strictly against the caste system). Many of these converts stopped attending Sikh Gurdwaras controlled by Jat Sikhs and built their own shrines upon arrival in the UK, Canada, and Fiji Island.[28][25] Ad-Dharmis comprise 11.48% of the total of Scheduled Caste communities in Punjab.[29][30][31]

Ahirwar

The Ahirwar, or Aharwar are Dalit members of a north Indian caste categorised among the Scheduled Castes of Chamar. Predominantly are members of the Scheduled Castes with a higher population in Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh.[32][33][34]

They are present, for example, in the state of Madhya Pradesh.[35] The 2001 Census of India recorded them in the Bundelkhand area and as the largest caste group in Lalitpur district, Uttar Pradesh, with a total population of 138,167.

Dhusia

Dhusia is a caste in India, associated with Chamars, Ghusiya, Jhusia or Jatav.[36][37] They are found in Uttar Pradesh,[38] and elsewhere.

Most of the Dhusia in Punjab and Haryana migrated from Pakistan after the partition of India. In Punjab, they are mainly found in Ludhiana, Patiala, Amritsar and Jalandhar cities. They are inspired by B. R. Ambedkar to adopt the surnames Rao[39] and Jatav.

Jatav

Jatav (also known as Jatava, Jatan, Jatua, Jhusia, Jatia, Jatiya) is an Indian Dalit community that is a sub-caste of the Chamar caste,[40] who are classified as a Scheduled Caste under modern India's system of positive discrimination.

According to the 2011 Census of India, the Jatav community of Uttar Pradesh comprised 54% of that state's total 22,496,047 Scheduled Caste population.[41]

Ravidassia/Ramdasia

Ravidassia is sect of Chamar Sikhs from Punjab who worship Guru Ravidass[42] and Ramdasia were historically a Sikh, Hindu sub-group that originated from the caste of leather tanners and shoemakers known as Chamar.[43][44]

Both the words Ramdasia and Ravidasia are also used inter changeably while these also have regional context. In Puadh and Malwa, largely Ramdasia is used while Ravidasia is predominantly used in Doaba.[45]

Chamar Diaspora

The Chamar diaspora consists of different subcastes who have emigrated from the different states of British India, as well as modern India, to other countries and regions of the world, as well as their descendants.[46] Apart from the Indian subcontinent, there is a large and well-established community of Chamars throughout different continents of the world, including Malaysia, Canada, Singapore, Caribbean, USA and UK, where they have established themselves as a trade diaspora.[47]

Mauritius

Ravived is a caste that is mainly found among Hindus in Mauritius.[48] The origin of this caste lay in an Indian caste named Chamar[49] This same caste is referred to as Ravidassia outside Mauritius, and this terminology is very seldom used in Mauritius.[50]

In the ship records on which Indian laborers migrated to Mauritius, around ten percent of the boarded people mentioned their caste as Chamar. After the establishment of caste hierarchies in Mauritius, the Chamar community families turned to the religious songs of Kabir and Ravidass for their own religious outlet. Slowly, they started adopting religious-sounding names from these devotional songs.[51]

Oceania

There is a sizeable population of Chamar Sikhs in Oceania too. Ravidassia Chamars from Doaba established the second gurdwara in the Oceania region in Nasinu on Fiji Island in 1939.[52] A Classical Study by W.H. Briggs in his book Punjabis in New Zealand, Briggs penned down the precise number of Ravidassias in New Zealand during the very first wave of immigration.[53]

United Kingdom

Chamar community from Punjab started immigrating from Punjab to Britain in 1950, and according to a book named 'Sikhs in Britain: An Annotated Bibliography' published in 1987, the population of the Ravidassia community in the West Midlands was around 30,000 during that period.[54] As of 2021, it is estimated that the Ravidasia population in Britain is around 70,000.[55]

Occupations

Chamars transitioning from tanning and leathercraft to the weaving profession adopt the identity of Julaha Chamar, aspiring to be acknowledged as Julahas by other communities. According to R. K. Pruthi, this change reflects a desire to distance themselves from the perceived degradation associated with leatherwork.[56]

Chamar Regiment

The 1st Chamar Regiment was an infantry regiment formed by the British during World War II. Officially, it was created on 1 March 1943, as the 27th Battalion 2nd Punjab Regiment. It was converted to the 1st Battalion and later disbanded shortly after World War II ended.[57] The Regiment, with one year of service, received three Military Crosses and three Military Medals[58] It fought in the Battle of Kohima.[59] In 2011, several politicians demanded that it be revived.[60]

Demographics

Chamar caste population in different states of India as per the 2011 census of India

| State, U.T | Population | Population % | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bihar[61] | 4,900,048 | 4.7% | Counted along Rabidas, Rohidas, Chamar, Charamakar |

| Chandigarh[62] | 59,957 | 5.68% | Counted along with other caste synonyms such as Chamars, Ramdasi, Ravidasi, Raigar and Jatia |

| Chhattisgarh[63] | 2,318,964 | 9.07% | Counted as Chamar, Satnami, Ahirwar, Raidas, Rohidas, Jatav, Bhambi and Surjyabanshi |

| NCT of Delhi[64] | 1,075,569 | 6.4 % | Counted along with other caste synonyms such as Jatav, Chamars, Ramdasia, Ravidasi, Raigar and Jatia |

| Gujarat[65] | 1,032,128 | 1.7% | Counted along with other caste synonyms such as Chamar, Bhambi, Asadaru, Chambhar, Haralaya, Rohidas, Rohit, Samgar |

| Haryana[66] | 2,429,137 | 9.58% | Counted along with other caste synonyms such as Jatav, Chamars, Ramdasia, Ravidasi, Raigar and Jatia |

| Himachal Pradesh[67] | 458,838 | 6.68% | Counted along with other caste synonyms such as Chamars, Ramdasia, Raigar and Jatia |

| Jammu and Kashmir[68] | 212,032 | 1.72% | Counted along with other caste synonyms such as Chamars, Ramdasia, Rohidas |

| Jharkhand[69] | 1,008,507 | 3.05% | Counted as Chamar, Mochi |

| Karnataka[70] | 605,486 | 1% | Counted as Rohidas, Rohit, Samgar, Haralaya, Chambhar, Chamar, Bhambi |

| Madhya Pradesh[71] | 5,368,217 | 7.39% | Counted as Chamar, Jatav, Bairwa, Bhambi, Rohidas, Raidas, Ahirwar,Satnami, Ramnami, Surjyabanshi |

| Maharashtra[72] | 1,411,072 | 1.25% | Counted as Rohidas, Chamar, Chambhar, Bhambi, Satnami, Ramnami, Haralaya, Rohit, Samagar, Bhambi |

| Punjab[73] | 3,095,324 | 11.15% | During the 2011 census in Punjab, 1017192 people were counted as addharmi in a separate caste cluster, which is another term for Ravidassias.[74][75]

In the same census, the Ravidassias cluster population was 2078132, and both clusters together made a population of 3095324 in Punjab, which is an 11.15% population of Punjab. |

| Rajasthan[76] | 2,491,551 | 3.63% | Counted along with other caste synonyms such as Chamars, Bhambi, Ramdasia, Ravidasi, Raigar, Haralaya, Chambhar and Jatia |

| Uttarakhand[77] | 548,813 | 5.44% | Counted as Chamar, Jatava, Dhusia, Jhusia |

| Uttar Pradesh[78] | 22,496,047 | 11.25% | Counted as Chamar, Jatava, Dhusia, Jhusia |

| West Bengal[79] | 1,039,591 | 1.13% | Counted as Chamar, Rabidas, Charamakar, Rishi |

Caste reservation

Chamar is classified as a scheduled caste in India. It is largely believed that among the scheduled castes, Chamar benefitted more from the caste reservation system as compared to other Dalit castes due to larger political representation of the group.[80]

Chamars in Nepal

The Central Bureau of Statistics of Nepal classifies the Chamar as a subgroup within the broader social group of Madheshi Dalits.[81] At the time of the 2011 Nepal census, 335,893 people (1.3% of the population of Nepal) were Chamar. The frequency of Chamars by province was as follows:

- Madhesh Province (4.2%)

- Lumbini Province (2.1%)

- Koshi Province (0.3%)

- Bagmati Province (0.0%)

- Gandaki Province (0.0%)

- Karnali Province (0.0%)

- Sudurpashchim Province (0.0%)

The frequency of Chamars was higher than national average (1.3%) in the following districts:[82]

- Parasi (7.4%)

- Siraha (5.7%)

- Parsa (4.7%)

- Bara (4.4%)

- Saptari (4.3%)

- Dhanusha (3.8%)

- Rautahat (3.8%)

- Kapilvastu (3.7%)

- Rupandehi (3.7%)

- Mahottari (3.6%)

- Sarlahi (3.6%)

- Banke (1.9%)

Notable people

- Guru Ravidass, was an Indian mystic poet-saint of the Bhakti movement during the 15th to 16th century CE.

- Mayawati, leader of Bahujan Samaj Party and Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh.[83]

- Mohan Lal Kureel was a British Indian Army officer who served in The Chamar Regiment and later an Indian National Congress politician in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh.[84]

- Jagjivan Ram, former Deputy Prime Minister of India[85]

- Kanshi Ram (1934–2006), founder of Bahujan Samaj Party and mentor of Mayawati Kumari[86]

- Navneet Kaur Rana - Former Actress and Former Member of Parliament[87]

- Ashok Tanwar - Former Member Parliament[88]

See also

References

- ^ "List of Scheduled Castes" (PDF). Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment. p. 18. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ Dr V.Vasanthi Devi (2021). A Crusade for Social Justice. South Vision Books. p. 253.

- ^ Rawat, Ramnarayan S. (23 March 2011). Reconsidering Untouchability: Chamars and Dalit History in North India. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-22262-6. Retrieved 21 September 2024.

- ^ Sarah Beth Hunt 2014, p. 23.

- ^ Yadav, Bhupendra (21 February 2012). "Aspirations of Chamars in North India". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 23 February 2012. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- ^ Malu, Preksha (21 July 2018). "Caste-igated: How Indians use casteist slurs to dehumanise each other". Sabrang Communications. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- ^ "Twitter Calls out Netflix's 'Jamtara' for Using Casteist Slur". The Quint. 18 January 2020. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- ^ Singh, Sanjay L. (20 August 2008). "Calling an SC 'chamar' offensive, punishable, says apex court". The Economic Times. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ Maren Bellwinkel-Schempp 2011, p. 106.

- ^ Sarah Beth Hunt 2014, p. 5.

- ^ Sarah Beth Hunt 2014, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Sarah Beth Hunt 2014, p. 30.

- ^ Sarah Beth Hunt 2014, p. 73.

- ^ Sarah Beth Hunt 2014, p. 5,33.

- ^ Maren Bellwinkel-Schempp 2011, p. 104.

- ^ Sarah Beth Hunt 2014, pp. 43, 76.

- ^ Sarah Beth Hunt 2014, p. 45.

- ^ Sarah Beth Hunt 2014, pp. 7, 23.

- ^ Sarah Beth Hunt 2014, pp. 8, 24.

- ^ Sarah Beth Hunt 2014, p. 55,72.

- ^ Badri Narayan (2012). Women Heroes and Dalit Assertion in North India: Culture, Identity and Politics. SAGE. pp. 89–90. ISBN 9780761935377.

- ^ Case Studies on Strengthening Co-ordination Between Non-governmental Organizations and Government Agencies in Promoting Social Development. United Nations (Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific). 1989. p. 72,73,74,75. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ Kaushal Kishore Sharma; Prabhakar Prasad Singh; Ranjan Kumar (1994). Peasant Struggles in Bihar, 1831-1992: Spontaneity to Organisation. Centre for Peasant Studies. p. 247. ISBN 9788185078885.

According to them, before the emergence of Naxalism on the scene and consequent resistance on the part of these hapless fellows, "rape of lower caste women by Rajput and Bhumihar landlords used to cause so much anguish among the lower cates, who, owing to their hapless situation, could not dare oppose them. In their own words, "within the social constraints , the suppressed sexual hunger of the predominant castes often found unrestricted outlet among the poor, lower caste of Bhojpur-notably Chamars and Mushars.

- ^ E M Rammohun; Amritpal Singh; A K Agarwal (2012). Maoist Insurgency and India's Internal Security Architecture. Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. p. 18. ISBN 978-9381411636. Consider the oppression of the lower castes in Bihar. In Bhojpur district of Bihar, the lower castes lived in utter poverty and were also subjected to social exploitation. Kalyan Mukherjee and Rajender Singh Yadav described that the oppression of the lower castes at the hands of the upper castes did not flow from numerical superiority, but rather from niches in the economic hierarchy apropos land ownership and the monopoly over labour. Further the culture of violence ensured that the Chamar or the Musahar never raise their heads in protest. Though begar was a thing of the past, the banihar worked often for nothing. Wearing a clean dhoti, remaining seated in the presence of the master, even on a cot outside his own hut, walking erect were taboo. When the evenings fell or in lonely stretches of field, the rape of his womenfolk by the landlord's lathieths and scions complete a picture of unbridled Bumihar, Rajput over lordship.

- ^ a b "Ad Dharm - SikhiWiki, free Sikh encyclopedia".

- ^ "Deras and Dalit Consciousness". Mainstream Weekly. 13 June 2009. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- ^ "'Ad-Dharm Movement was the Revolt Against the Hinduism' – Saheb Kanshi Ram's Speech at Sikri, Punjab, 12th February 2001 | Velivada". velivada.com. 3 November 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ Judge, Paramjit S. (2002). "Punjabis in England: The Ad-Dharmi Experience". Economic and Political Weekly. 37 (31): 3244–3250. JSTOR 4412439.

- ^ "Punjab Data Highlights: The Scheduled Castes" (PDF).

- ^ Singh, IP (13 July 2020). "Give 'Adi-dharmi' as religion in 2021 census: Ravidassia leaders". The Times of India. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ^ "Why Everyone in Punjab loves a Dalit CM". NewsClick. 22 September 2021. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ^ Abbasi, A. A., ed. (2001). Dimensions of Human Cultures in Central India: Professor S.K. Tiwari Felicitation Volume. Sarup & Sons. p. 255. ISBN 978-8-17625-186-0.

- ^ Chaudhary, Shyam Nandan (2007). Dalit Agenda and Grazing Land to Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. Concept Publishing Co. p. 119. ISBN 9788180693816.

- ^ Nandu Ram (2009). Beyond Ambedkar: Essays on Dalits in India. Har Anand Publications. p. 164. ISBN 9788124114193.

- ^ Ahmad, Aijazuddin (2009). Geography of the South Asian subcontinent : a critical approach. New Delhi: Concept Pub. Co. ISBN 978-8-18069-568-1.

- ^ "Lokniti" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ "The Inhabitants". sultanpur.nic.in. Archived from the original on 30 March 2009.

- ^ "Social Justice" (PDF).

- ^ Verma, A. K. (December 2001). "UP: BJP's Caste Card". Economic and Political Weekly. 36 (48): 4452–4455. JSTOR 4411406.

- ^ "Chasing the Dalit vote in U.P." The Hindu. 8 May 2014. Retrieved 6 September 2024.

- ^ "Jatavs on top of SC population in UP". The Times of India. 4 July 2015.

- ^ Chander, Rajesh K. (1 July 2019). Combating Social Exclusion: Inter-sectionalities of Caste, Gender, Class and Regions. Studera Press. ISBN 978-93-85883-58-3. Retrieved 6 September 2024.

- ^ Chander, Rajesh K I. (2019). Combating Social Exclusion: Intersectionalities of Caste, Class, Gender and Regions. Studera Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-93-85883-58-3.

- ^ Ghuman, Paul (May 2011). British Untouchables A Study of Dalit Identity and Education. Ashgate Publishing, Limited. p. iX. ISBN 978-0754648772.

- ^ "Punjab's dalit conundrum: A look into Sikhs' caste identity". The Times of India. 30 September 2021. Retrieved 7 September 2024.

- ^ Singh, I. J. Bahadur (1987). Indians in the Caribbean. Sterling. ISBN 978-0-7465-0074-3. Retrieved 6 September 2024.

- ^ "Seattle: Why US city's ban on caste discrimination is historic for South Asian Americans". 22 February 2023. Retrieved 6 September 2024.

- ^ "Understanding the caste system in Mauritius". 6 April 2021.

- ^ http://mujournal.mewaruniversity.org/JIR%203-4/JIR3-4.pdf

- ^ Claveyrolas, Mathieu (2015). "The 'Land of the Vaish'? Caste Structure and Ideology in Mauritius". South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal. doi:10.4000/samaj.3886.

- ^ Younger, Paul (30 November 2009). New Homelands: Hindu Communities in Mauritius, Guyana, Trinidad, South Africa, Fiji, and East Africa. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-974192-2. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ Kahlon, S.S. (2016). Sikhs in Asia Pacific: Travels Among the Sikh Diaspora from Yangon to Kobe. Taylor & Francis. p. 337. ISBN 978-1-351-98741-7. Retrieved 6 September 2024.

- ^ McLeod, W. H. (5 December 2006). "Punjabis in New Zealand: A History of Punjabi Migration, 1890-1940". Google. Retrieved 6 September 2024.

- ^ Tatla, Darshan Singh; Nesbitt, Eleanor M (1987). Sikhs in Britain An Annotated Bibliography. Centre for Research in Ethnic Relations, University of Warwick. p. 66. ISBN 9780948303067. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ Kumar, Pramod (2021). The Idea of New India Essays in Defence of Critical Thought. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781000485714. Retrieved 6 September 2024.

- ^ Pruthi, R. K. (2004). Indian caste system. Discovery. p. 189. ISBN 9788171418473. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ^ Sharma 1990, p. 28.

- ^ Sharma, Gautam (1990). Valour and Sacrifice: Famous Regiments of the Indian Army. Allied Publishers. pp. 26–. ISBN 978-81-7023-140-0.

- ^ "The Battle of Kohima" (PDF).

- ^ "RJD man Raghuvansh calls for reviving Chamar Regiment". indianexpress.com. 8 March 2011. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- ^ SC-14: Scheduled caste population by religious community, Bihar - 2011 (2021) India. Available at: https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/catalog/2115 (Accessed: 2 September 2024).

- ^ SC-14: Scheduled caste population by religious community, Chandigarh - 2011 (2021) India. Available at: https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/catalog/2109 (Accessed: 2 September 2024).

- ^ SC-14: Scheduled caste population by religious community, Chhattisgarh - 2011 (2021) India. Available at: https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/catalog/2125 (Accessed: 2 September 2024).

- ^ SC-14: Scheduled caste population by religious community, NCT of Delhi - 2011 (2021) India. Available at: https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/catalog/2112 (Accessed: 2 September 2024).

- ^ SC-14: Scheduled caste population by religious community, Gujarat - 2011 (2021) India. Available at: https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/catalog/2127 (Accessed: 2 September 2024).

- ^ SC-14: Scheduled caste population by religious community, Haryana - 2011 (2021) India. Available at: https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/catalog/2111 (Accessed: 2 September 2024).

- ^ SC-14: Scheduled caste population by religious community, Himachal Pradesh - 2011 (2021) India. Available at: https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/catalog/2107 (Accessed: 2 September 2024).

- ^ SC-14: Scheduled caste population by religious community, Jammu & Kashmir - 2011 (2021) India. Available at: https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/catalog/2106 (Accessed: 2 September 2024).

- ^ SC-14: Scheduled caste population by religious community, Jharkhand - 2011 (2021) India. Available at: https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/catalog/2123 (Accessed: 2 September 2024).

- ^ SC-14: Scheduled caste population by religious community, Karnataka - 2011 (2021) India. Available at: https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/catalog/2132 (Accessed: 2 September 2024).

- ^ SC-14: Scheduled caste population by religious community, Madhya Pradesh - 2011 (2021) India. Available at: https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/catalog/2126 (Accessed: 2 September 2024).

- ^ SC-14: Scheduled caste population by religious community, Maharashtra - 2011 (2021) India. Available at: https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/catalog/2130 (Accessed: 2 September 2024).

- ^ SC-14: Scheduled caste population by religious community, Punjab - 2011 (2021) India. Available at: https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/catalog/2108 (Accessed: 2 September 2024).

- ^ Ashraf, Ajaz (22 September 2021). "Why everyone in Punjab loves a Dalit C.M". News Click. Retrieved 2 September 2024.

- ^ Singh, IP (11 March 2022). "Punjab ex-CM Charanjit Singh Channi's scheduled caste factor overlooked?". TOI. Retrieved 2 September 2024.

- ^ SC-14: Scheduled caste population by religious community, Rajasthan - 2011 (2021) India. Available at: https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/catalog/2113 (Accessed: 2 September 2024).

- ^ SC-14: Scheduled caste population by religious community, Uttarakhand - 2011 (2021) India. Available at: https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/catalog/2110 (Accessed: 2 September 2024).

- ^ SC-14: Scheduled caste population by religious community, Uttar Pradesh - 2011 (2021) India. Available at: https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/catalog/2114 (Accessed: 2 September 2024).

- ^ SC-14: Scheduled caste population by religious community, West Bengal - 2011 (2021) India. Available at: https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/catalog/2122 (Accessed: 2 September 2024).

- ^ Rajinder Puri (3 February 2022). "Who Gains From Reservation?". Outlook India.

- ^ Population Monograph of Nepal, Volume II

- ^ "2011 Nepal Census, District Level Detail Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 March 2023. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ "Mayawati talks of a secret successor". India Today. Indo-Asian News Service. 9 August 2008. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ "SC Commission Asks Defence Secretary Why 'Chamar Regiment' Shouldn't be reinstated". News18. March 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- ^ Roy, Kaushik (2016). "Indian society and the soldier: will the twain ever meet?". In Pant, Harsh V. (ed.). Handbook of Indian Defence Policy: Themes, structures and doctrines. Routledge. p. 67. ISBN 978-1138939608. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

In 1970, when Babu Jagjivan Ram (himself, a chamar) became the defence minister, he attempted to raise the chamar regiment.

- ^ "I will be the best PM and Mayawati is my chosen heir". Indian Express. 2 May 2003.

...I am a chamar from Punjab...

- ^ Bawa, Anmol Kaur (23 February 2024). "Can 'Sikh Chamar' Be Regarded As 'Mochi' Caste In Maharashtra? Supreme Court Considers In Navneet Kaur Rana's Case". www.livelaw.in. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ English, The Mooknayak (18 September 2024). "How INLD is Leading the Charge for Deprived Scheduled Castes Empowerment in Haryana". The Mooknayak English - Voice Of The Voiceless. Retrieved 25 October 2024.

Bibliography

- Maren Bellwinkel-Schempp (2011). Peter Schalf (ed.). Neuer Buddhismus als gesellschaftlicher Entwurf (PDF). Uppsala University. doi:10.1515/olzg-2015-0120. ISBN 978-91-554-8076-9. S2CID 164806488.

- Sarah Beth Hunt (2014). Hindi Dalit Literature and the Politics of Representation. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-73629-9.

Further reading

- Briggs, George W. (1920). The Religious Life of India — The Chamars. Calcutta: Association Press. ISBN 1-4067-5762-4.

- Rawat, Ramnarayan S. (2011). Reconsidering Untouchability: Chamars and Dalit History in North India. Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253222626.

- Schmalz, Mathew N. (2004). "A Bibliographic Essay on Hindu and Christian Dalit Religiosity". Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies. 17: 55–65. doi:10.7825/2164-6279.1318. ISSN 2164-6260.

- Dalit communities

- Leatherworking castes

- Hindu denominations

- Ethnic groups in Nepal

- Ethnic groups in India

- Scheduled Castes of Assam

- Scheduled Castes of Haryana

- Scheduled Castes of Jharkhand

- Scheduled Castes of Delhi

- Scheduled Castes of Rajasthan

- Social groups of Punjab, India

- Scheduled Castes of Madhya Pradesh

- Scheduled Castes of Odisha

- Scheduled Castes of Gujarat

- Scheduled Castes of Bihar

- Scheduled Castes of West Bengal

- Scheduled Castes of Andhra Pradesh

- Scheduled Castes of Dadra and Nagar Haveli

- Scheduled Castes of Himachal Pradesh

- Scheduled Castes of Chhattisgarh

- Scheduled Castes of Uttar Pradesh

- Scheduled Castes of Uttarakhand

- Scheduled Castes of Maharashtra

- Scheduled Castes of Jammu and Kashmir

- Scheduled Castes of Kerala

- Scheduled Castes of Mizoram

- Scheduled Castes of Meghalaya