Macombs Dam Bridge

Macombs Dam Bridge | |

|---|---|

View of the over-water span from the south; the Bronx approach viaduct can be seen at right | |

| Coordinates | 40°49′41″N 73°56′02″W / 40.82806°N 73.93389°W |

| Carries | 4 lanes of roadway |

| Crosses | Harlem River |

| Locale | Manhattan and the Bronx, New York City |

| Named for | Macombs Dam |

| Owner | City of New York |

| Maintained by | NYCDOT[1] |

| Heritage status | New York City designated landmark |

| Preceded by | High Bridge |

| Followed by | 145th Street Bridge |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | swing[1] and camelback bridge |

| Total length | 2,540 ft (770 m)[1] |

| Longest span | 408 ft (124 m)[1] |

| Clearance below | 25 ft (7.6 m) |

| No. of lanes | 4 |

| History | |

| Construction cost | $25 million (viaduct, in 2023 values) $48 million (over-water span, in 2023 values) $181 million (rehabilitation)[1] |

| Opened | May 1, 1895[1] |

| Statistics | |

| Daily traffic | 38,183 (2016)[2] |

| Designated | January 14, 1992 |

| Reference no. | 1629 |

| Designated entity | 155th Street Viaduct and over-river span |

| Location | |

| |

The Macombs Dam Bridge (/məˈkuːmz/ mə-KOOMZ; also Macomb's Dam Bridge) is a swing bridge across the Harlem River in New York City, connecting the boroughs of Manhattan and the Bronx. The bridge is operated and maintained by the New York City Department of Transportation (NYCDOT).

The Macombs Dam Bridge connects the intersection of 155th Street and Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard (Seventh Avenue), located in Manhattan, with the intersection of Jerome Avenue and 161st Street, located near Yankee Stadium in the Bronx. The 155th Street Viaduct, one of the bridge's approaches in Manhattan, carries traffic on 155th Street from Seventh Avenue to the intersection with Edgecombe Avenue and St. Nicholas Place. The bridge is 2,540 feet (770 m) long in total, with four vehicular lanes and two sidewalks.

The first bridge at the site was constructed in 1814 as a true dam called Macombs Dam. Because of complaints about the dam's impact on the Harlem River's navigability, the dam was demolished in 1858 and replaced three years later with a wooden swing bridge called the Central Bridge, which required frequent maintenance. The current steel span was built between 1892 and 1895, while the 155th Street Viaduct was built from 1890 to 1893; both were designed by Alfred Pancoast Boller. The Macombs Dam Bridge is the third-oldest major bridge still operating in New York City, and along with the 155th Street Viaduct, was designated a New York City Landmark in 1992.

Description

[edit]The Macombs Dam Bridge was named after Robert Macomb, the son of merchant Alexander Macomb.[3][4] It is composed of an over-water span and the 155th Street Viaduct, both of which were designed by consulting engineer Alfred Pancoast Boller.[5][6] The bridge's total length is 2,540 feet (770 m), including its approach viaducts.[7][8]

As of 2019[update], the Macombs Dam Bridge carries New York City Transit's Bx6 and Bx6 SBS bus routes.[9][10] In 2016, the New York City Department of Transportation reported an average daily traffic volume in both directions of 38,183,[2] with a peak of 55,609 in 1957.[11] Between 2000 and 2014, the bridge opened for vessels 32 times.[12]

Over-river span

[edit]

The Macombs Dam Bridge includes a swing bridge over the Harlem River, pivoting around a small masonry island in the middle of the river. The swinging span is the oldest remaining swing bridge in New York City that retains its original span. According to the New York City Department of Transportation (NYCDOT), which maintains the bridge, it is the city's third-oldest major bridge still in operation.[8] It is variously cited as being 408 or 415 feet (124 or 126 m) long.[8][13] It has four lanes for vehicular traffic and a sidewalk on each side for pedestrians.[4][8][14] The roadway measures 40 feet (12 m) wide and the sidewalks measure 9.9 feet (3.0 m) wide.[4][14][15] The total width of the deck, including additional space for supports and railings, is 65 feet (20 m).[13]

The span's trusswork consists of concave chords running along the top. The chords taper up toward a square section in the center of the span, which is topped by four finials. On the Manhattan side, there is a plaque stating the year 1894, the words "Central Bridge", and the name of the bridge's major engineers.[13] The design has been compared to a "raffish tiara" due to the presence of the Gothic Revival-style abutments.[16] The swing span can be rotated around a tower located below the center of the deck, which in turn is located on the small masonry island. On both sides of the island are shipping channels with 150 feet (46 m) of horizontal clearance. When closed, the bridge provides 25 feet (7.6 m) of vertical clearance.[7][8] The swinging portion weighs 2,400 short tons (2,100 long tons; 2,200 t) and is turned by two concentric drums: the inner drum has a diameter of 36 feet (11 m) and the outer has a diameter of 44 feet (13 m).[14] At the time of its construction, Macombs Dam Bridge's over-river span was said to be among the largest drawbridges built to date,[16] or the heaviest movable mass in the world.[17][18]

On either bank of the river are pairs of stone end piers with shelter houses.[7][13] The shelter houses contain red tile roofs and are used by the bridge tender. Latticework gates are located near these end piers, blocking off access to the span when it is in the "open" position. Many of the original railings have been replaced.[13]

Viaducts

[edit]There are three approaches to the bridge. Two are from the Manhattan side (the 155th Street Viaduct and the Seventh Avenue approach), while the third leads to the intersection of Jerome Avenue and 161st Street in the Bronx.[19]

155th Street Viaduct

[edit]

At the western end of the over-water span is a long steel viaduct, carrying two sidewalks and two lanes of traffic in each direction. The viaduct stretches from the intersection of 155th Street, Edgecombe Avenue, and St. Nicholas Place, at its western end, to the intersection of Macombs Place, Macombs Dam Bridge, and Seventh Avenue (also Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard) at its eastern end.[20] There are traffic lights at both ends of the 155th Street Viaduct. An unconnected lower section of 155th Street runs at ground level under the viaduct.[19]

The viaduct stretches 1,600 feet (490 m) was built due to the presence of Coogan's Bluff at its western end, some 110 feet (34 m) above the river.[21][22] It passes over an unconnected section of 155th Street located at the bottom of the cliff.[22] The viaduct is supported by 31 girders; the western 22 girders contain horizontal, diagonal, and vertical bracing, while the eastern 9 girders do not contain bracing. The extreme western end of the viaduct is located on a granite and limestone abutment; the roadway retains its original ornamental iron railings designed by Hecla Iron Works, with a tall chain-link fence above. The rest of the viaduct contains utilitarian metal railings and tall chain-link fences.[22]

The viaduct was designed similar to a landscaped boulevard or parkway, with observation decks projecting outward from the viaduct's sidewalks.[21] Additionally, four long metal staircases originally connected the viaduct and the lower level of 155th Street; these stairs had canopies covering their upper flights. By 1992, only two of these stairs remained on the west side of Eighth Avenue,[22] and by 2000, both remaining stairs had deteriorated too severely to be restored.[21] On the western end of the viaduct, a stone staircase connects the north sidewalk of the viaduct and the lower section of 155th Street.[22] A 28-foot-tall (8.5 m) column with a weather vane, lamp, and drinking fountain is at the western end of the viaduct.[21][23] The fountain—sometimes called the Hooper Fountain after its donor, businessman John Hooper[23][24]—still exists on the southeast corner of the 155th Street Viaduct and Edgecombe Avenue.[22] Just east of the column, a path leads south to Jackie Robinson Park.[25]

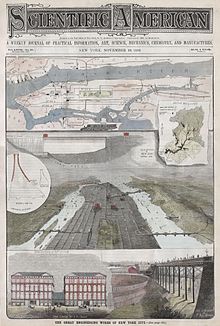

Before the viaduct was built, the 155th Street station of the elevated IRT Ninth Avenue Line, located along Eighth Avenue at the bottom of the cliff, could only be reached from the top by a long staircase.[26] A Scientific American magazine article in 1890 stated that "To draw a load up the hill a team has to be taken a mile or more to the south".[21][27]

Seventh Avenue approach

[edit]The other approach viaduct to the over-water span is from Seventh Avenue and Macombs Place (formerly Macombs Dam Road).[19] It is 140 feet (43 m) long. The approach ramp is carried by several steel plate girders, as well as three Warren truss spans on the approach's southern side, which are carried by box girders. Part of the approach ramp is carried on an abutment pier, which contains a limestone-and-granite facade. A stairway leads from the Seventh Avenue approach's western sidewalk to the lower level of 155th Street;[13] a corresponding stair on the eastern sidewalk of Macombs Place was demolished when the Seventh Avenue ramp was rebuilt in 1930.[28]

As originally laid out, Macombs Place provided access to Eighth Avenue (Frederick Douglass Boulevard), which was located at the bottom of Coogan's Bluff and was bypassed by the viaduct.[29] Original plans did not provide for a connection to Seventh Avenue, but a curved ramp to Seventh Avenue was added by the time the bridge was opened.[30][31] The approach was rebuilt in 1931 to provide direct access to Seventh Avenue.[32] As of 2020[update], it provides access to southbound Macombs Place and both directions of Seventh Avenue. At 152nd Street, a connecting road descends from the median of Seventh Avenue, connecting to the lower section of 155th Street.[19]

Bronx approach

[edit]

At the eastern end of the over-water span, there are two Warren truss spans, followed by a camelback span over the tracks of the Metro-North Railroad's Hudson Line.[7][13] Past the camelback span, the bridge intersects with the on- and off-ramps to and from the southbound Major Deegan Expressway. To the northeast, a steel approach road leads to Jerome Avenue, which extends north into the Bronx and Westchester County, and there are cloverleaf ramps to and from the northbound Major Deegan Expressway.[19] The approach road consists of six steel-and-concrete spans across the expressway, as well as six more Warren trusses. These spans are supported by girders located atop granite piers.[22] The approach road contains another intersection, with 161st Street, before terminating at Jerome Avenue.[19] The grade of the approach road is 1%.[14]

History

[edit]Previous spans

[edit]

The original river crossing on the site was called Macombs Dam and was built along with the since-demolished lock-and-dam system on the Harlem River.[4][7][8] The dam was opened in 1814,[7][33] and the bridge was finished in 1815[18] or 1816.[7][34] Macombs Dam's capacity was limited by its narrow width, as the manned lock only measured 7 by 7 feet (2.1 by 2.1 m),[7] and by the mid-19th century, no longer used as a dam.[33] In one incident in September 1839, local residents breached the dam over several days, and their actions were later reinforced by New York Supreme Court despite the operator's objections.[7][35][36] Following legislature passed by the city in 1858, the dam was demolished that year, and was mandated to be replaced with a swing bridge.[3][7][18]

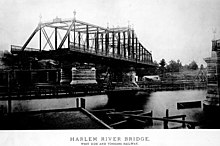

The wooden Central Bridge, a swing bridge across the Harlem River, followed in 1860 or 1861.[15][18] The span's construction was initially supposed to cost $10,000, but ultimately cost nine times as much.[18] The wooden swing bridge included a rotating square tower situated atop a small island in the center of the river; the span itself was supported by iron rods attached to the tower.[15] Because of the number of wooden parts, it often required maintenance.[8] The city held a contest in 1875 for the installation of "a new wooden draw" to replace the existing Central Bridge.[37] In 1877, the swinging component's square-shaped frame was removed and an A-frame was installed.[7][15][18] The approach spans were subsequently replaced with iron in 1883, and the wooden span was rebuilt in 1890.[15][18] The rebuilt span was 210 feet (64 m) long and 18 feet (5.5 m) wide, with two 4-foot-wide (1.2 m) sidewalks, as well as approach ramps measuring 180 feet (55 m) long.[15] These improvements did not help the public's reputation of the bridge, and one driver was quoted as saying, "They ought to keep it for clam wagons, though no clam with any regard for himself would ever cross the bridge."[38]

Planning and construction

[edit]By the late 1880s, landowners in Upper Manhattan were advocating for development of Washington Heights, the then-sparsely-populated area atop Coogan's Bluff, the high cliff to the west of Macombs Dam.[39] At the time, there were few options for traveling between the top and bottom of Coogan's Bluff.[40] Another reason for developing this region of Manhattan was the opening of the Polo Grounds stadium at the bottom of Coogan's Bluff in 1890.[39] By 1886, local landowners had come to an agreement that a viaduct was needed to connect the top of Coogan's Bluff and the Central Bridge.[39] The next year, the New York state legislature passed a law that enabled the construction of a viaduct connecting the high point of Coogan's Bluff to the Central Bridge.[39][41] Around the same time, the Central Bridge was slated to be rebuilt as a result of the River and Harbor Act, passed by the United States Congress in 1890.[39] As part of the act, bridges on the Harlem River with low vertical clearance were to be replaced with those with at least 24 feet (7.3 m) of clearance during mean high water springs. Drawbridges and swing spans were determined to be most suitable for this purpose.[39][42][43]

Structural engineer Alfred Pancoast Boller was hired to design the viaduct; his plans were officially approved in May 1890 at an estimated cost of $514,000, to be split evenly between the city and landowners.[39] The city hired Herbert Steward to be the contractor; the Union Bridge Company for structural steel; and Hecla Iron Works for iron ornamentation.[44] In June 1890, Boller was also hired for the over-water span. Boller submitted his plans for the over-water span that November; the plans entailed a smaller approach viaduct in the Bronx to cross over the swamp on that side.[45] Work on the 155th Street Viaduct began in December 1890.[46]

At the end of 1891, the foundations for the 155th Street Viaduct's support structure, as well as the masonry abutment at the viaduct's western end, had been constructed. However, further work at the viaduct's east end was delayed until the over-water span's foundations could be laid.[39][47] The contract for the over-water span and Bronx approach was given to the Passaic Rolling Mill Company in March 1892, and work on that segment began two months later. The contractors and suppliers for the 155th Street Viaduct were also contracted for the over-water span.[45] As the old bridge was about to be closed, residents of the town of Tremont, Bronx, expressed concerns that one of their few links to Manhattan would be temporarily severed.[48] Ultimately, the old drawbridge was floated slightly north to 156th Street while the new span was constructed immediately adjacent.[45][49][50] The old bridge remained there until the new span was completed, at which point the old span was demolished.[49]

After the height of the over-water span's deck had been established, two falsework rails were placed on the outer edges of the span, along which a rolling scaffold traveled.[45] Two different methods were used to construct the foundations for the over-water span. A caisson was used for the western bank's pier and the central pivoting "island", while a cofferdam was used for the eastern bank's pier.[45][51] The latter required a modification to the original contract "owing to the great depth of swampy bottom".[52] The design of the short span over the Hudson Line railroad tracks was likely also changed when the contract modification was made.[45]

By late 1892, the 155th Street Viaduct was nearly completed and the Real Estate Record stated that pedestrians were already using the viaduct to access the elevated line. However, there were disputes over the ramp between Seventh Avenue and the over-water span.[29][39] In the initial plans, the 155th Street Viaduct lacked a direct connection to Seventh Avenue.[30] A rocky outcropping obstructed the line of view between Seventh Avenue and the bridge, so the builders decided to destroy the rock.[29][45] The city also acquired land for a park between Macombs Dam Road, Seventh Avenue, and 153rd Street.[53] Additionally, there were problems in coordinating work on the viaduct and over-water span, since the two segments intersected at an angle.[29][39] An additional contract for a second Bronx approach from Sedgwick and Ogden Avenues was designed by Boller in January 1893,[45] and was approved by the New York State Legislature.[54] In 1894, the contract for the second Bronx approach was awarded to Passaic,[45] while the contract for the over-water span's ornamentation was given to Valentine Cook & Son.[45][55]

1890s to 1930s

[edit]

The 155th Street Viaduct opened on October 10, 1893.[21][45] The over-water span opened "without any particular ceremony" a year and a half later, on May 1, 1895.[8][56] The viaduct cost $739,000 (about $25 million in 2023),[45] while the over-water span cost $1.3 million (equal to $48 million in 2023);[8] however, the total cost of the over-water span including land acquisition was $1.774 million (about $65 million in 2023).[45] The new bridge was also called the Central Bridge, and though a plaque bearing this name still can be seen on the swing span, the name never stuck.[20] The old "Macombs Dam" name remained in popular use, and the bridge was officially renamed with its original moniker in 1902.[7][8] The 155th Street Viaduct and over-water span were formerly operated by two different entities. The over-water span was erected by the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation before being transferred to the Bridge Department in 1898, while the 155th Street Viaduct was erected by the Department of Public Works and was transferred to the Manhattan borough president's office in 1898.[28]

A trolley franchise was awarded to the Union Railroad Company in 1903, providing Bronx residents with a direct connection to the Eighth Avenue trolley.[57] The first trolley traveled over the Macombs Dam Bridge in 1904.[58][59] Due to the increasing prevalence of trolleys and automobiles, there was a decrease in horse-drawn carriages that used the bridge. Also in 1904, the steam engine that powered the movable over-water span was replaced with a 24 horsepower (18 kW) electric motor,[59] which itself was replaced with a 52 horsepower (39 kW) motor in 1917.[28] The New York City Department of Plant and Structures assumed control of the over-water span in 1916, and five years later it also had jurisdiction of the 155th Street Viaduct.[28]

In 1920, while Yankee Stadium was under construction, ramps were built on the Bronx side of the Macombs Dam Bridge,[8][59] leading to 161st Street.[22] As part of this project, the staircase on the northern facade of the Bronx abutment was demolished, and a corresponding stair on the southern facade was built.[59] On the Manhattan side, a rebuilt approach from Seventh Avenue and 151st Street to the bridge, as well as a rebuilt triangular plaza between Seventh Avenue and Macombs Dam Road, was opened in 1931.[32][59][60] The approach was built on land donated by John D. Rockefeller Jr.[32] The new approach, designed by Andrew J. Thomas, entailed rebuilding the formerly-straight Macombs Dam Road approach to a "flared polygonal" route, which required extending the masonry abutment there.[59] In 1938, both the over-water span and the viaduct became the jurisdiction of the Department of Public Works.[28]

1940s to present

[edit]Part of the pedestrian railing was damaged in 1949 after a boat's boom ran into the over-water span.[61] Around the same time, from 1949 through 1951, the approach to Ogden and Sedgwick Avenues in the Bronx was demolished to make way for the construction of the Major Deegan Expressway.[59] Three segments of truss bridge were also removed during this time, and the removed truss segment over the expressway's path was replaced with a new steel deck. The trolley tracks were also removed c. 1950, and many of the original decorative and lighting fixtures were replaced in the early 1960s.[13]

The Transportation Administration assumed control of the bridge and viaduct in 1966.[28] Mayor John Lindsay proposed enacting tolls along the University Heights Bridge, as well as all other free bridges across the East and Harlem rivers, in 1971.[62][63] The proposal failed in 1977 after the United States Congress moved to ban tolls on these bridges.[64] A new interchange on the Bronx side opened in 1977, providing easier access to Yankee Stadium.[65] The same year, jurisdiction passed to the NYCDOT, which still operates and maintains the bridge and viaduct.[28]

By 1988, the NYCDOT listed the Macombs Dam Bridge as one of 17 bridges citywide that urgently needed restoration. The work, initially expected to cost $34 million, would pay for the restoration of steel brackets and deteriorated concrete supports.[66] The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission designated the Macombs Dam Bridge and the 155th Street Viaduct as a city landmark on January 14, 1992.[67][68] The NYCDOT conducted a $145 million overhaul of the bridge between 1999 and 2004.[4] As part of the renovation, the NYCDOT replaced the deck of the bridge, and renovated the structural elements of the approach viaducts and the four ramps to and from the Major Deegan Expressway.[69] The over-water span was also repainted and the electrical systems were replaced.[4] Simultaneously, the NYCDOT also assessed the Macombs Dam Bridge and 155th Street Viaduct for a seismic-retrofitting project, which at the time was slated to be completed between 2010 and 2013 for $36 million.[69] Despite the low probability of earthquakes in the area, the project had been proposed after more stringent building codes had been implemented in 2003.[70][71]

Critical reception

[edit]

Even while under construction, the Macombs Dam Bridge and the 155th Street Viaduct were favorably appraised by contemporary media.[72] Scientific American praised the design of the ornamental iron handrails and lampposts in 1890.[27] Two years later, the Engineering News-Record said that the two structures comprised "two of the parts of a grand system of improvements which will [...] transform that section of the city of New York."[14]

In 1895, after the bridge was completed, the Real Estate Record called the bridge "a beautiful piece of engineering work splendidly conceived."[73] Bridge engineer Martin Gay praised the masonry's "fine lines" and the "graceful sweep" of the over-water span's upper chord in 1904.[49] Architectural critic Montgomery Schuyler stated that the Macombs Dam Bridge was "the most pretentious and costly" of the Harlem River swing bridges, and that the Macombs Dam and University Heights Bridges were "highly creditable works, in an artistic as well as in a scientific sense."[74][a] The writer Sharon Reier, in the book "The Bridges of New York", referred to the Macombs Dam Bridge and the University Heights Bridge as "the only movable bridge[s] across the Harlem [...] which warrants a walking tour".[16] After Boller's death in 1912, a colleague wrote that the Macombs Dam Bridge was one of several spans designed by Boller that were "characterized by their originality and boldness of design".[17] The painter Edward Hopper depicted the bridge in a 1935 painting of the same name.[59]

Similar spans

[edit]

Boller designed several bridges across the surrounding section of the Harlem River.[16][72] Two of them were built to the south of the Macombs Dam Bridge. These spans were the 145th Street Bridge and the Madison Avenue Bridge, which originally opened in 1905 and 1910, respectively.[8][16] Though the 145th Street Bridge was replaced in 2006,[76] writer Sharon Reier had described the original 145th Street Bridge as an "uninspired copy" of the Macombs Dam Bridge.[16]

Immediately to the north of the Macombs Dam Bridge was the Putnam Bridge, also designed by Boller. The New York City Subway's now-demolished Ninth Avenue elevated line ran over the bridge, connecting with the IRT Jerome Avenue Line (current 4 train). The bridge opened in 1880, and was demolished after that portion of the Ninth Avenue line stopped operating in 1958.[77][78]

See also

[edit]- List of bridges documented by the Historic American Engineering Record in New York (state)

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan above 110th Street

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in the Bronx

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ Though the original text states "the bridge at Spuyten Duyvil",[74] it refers to the University Heights Bridge, which was relocated. Initially connecting Inwood with Marble Hill, both in Manhattan, it was floated southward on the Harlem River in 1908 to connect Inwood with University Heights, Bronx.[75]

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f Michael R. Bloomberg, City of New York (January 23, 2004). "New York City's Harlem River Bridges: The Reauthorization of the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 24, 2017. Retrieved December 2, 2017.

- ^ a b "New York City Bridge Traffic Volumes" (PDF). New York City Department of Transportation. 2016. p. 9. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 11, 2018. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ a b "Macombs Dam Park : NYC Parks". Macombs Dam Park Highlights. June 26, 1939. Archived from the original on January 4, 2020. Retrieved January 4, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (2010). The Encyclopedia of New York City (2nd ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 778. ISBN 978-0-300-11465-2.

- ^ White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot; Leadon, Fran (2010). AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 547. ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- ^ Reier 2000, p. 85.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Ensel, Douglas; Marchese, Shayna (March 11, 2010). "Macomb's Dam Bridge". Bridges in the New York Metropolitan Area. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Harlem River Bridges". nyc.gov. New York City Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on January 18, 2016. Retrieved January 12, 2016.

- ^ "Manhattan Bus Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. July 2019. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ "Bronx Bus Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. October 2018. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ New York City Department of Transportation (March 2010). "2008 New York City Bridge Traffic Volumes" (PDF). p. 74. Archived from the original on December 25, 2018. Retrieved June 27, 2010.

- ^ "Bridges and Tunnels Annual Condition Report" (PDF). New York City Department of Transportation. 2014. p. 147. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 12, 2021. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Landmarks Preservation Commission 1992, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e "The Harlem River Bridge at 155th Street, New York". Engineering News-record (v. 27). McGraw-Hill Publishing Company: 526–527. 1892. Archived from the original on June 28, 2022. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Gay 1905, p. 72.

- ^ a b c d e f Reier 2000, pp. 85–87.

- ^ a b American Society of Civil Engineers (1916). Transactions. New York. pp. 1654–1655.

- ^ a b c d e f g Landmarks Preservation Commission 1992, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e f "Macombs Dam Bridge" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ a b New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission; Dolkart, Andrew S.; Postal, Matthew A. (2009). Postal, Matthew A. (ed.). Guide to New York City Landmarks (4th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 204–205. ISBN 978-0-470-28963-1.

- ^ a b c d e f Gray, Christopher (July 9, 2000). "Streetscapes/The 155th Street Viaduct; An Elevated 1893 Roadway With a Lacy Elegance". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 11, 2020. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Landmarks Preservation Commission 1992, p. 10.

- ^ a b Tauranac, J.; Gerhardt, K. (2018). Manhattan's Little Secrets: Uncovering Mysteries in Brick and Mortar, Glass and Stone. Globe Pequot Press. p. 254. ISBN 978-1-4930-3048-4. Archived from the original on April 10, 2022. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (October 31, 2013). "Where Horses Wet Their Whistles". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 10, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ Most, Jennifer (April 10, 2007). "Jackie Robinson (Colonial Park) Play Center Exterior" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. p. 14. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 16, 2021. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ "On Washington Heights" (PDF). The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. 46 (1173): 300. September 6, 1890. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2020 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ a b "The 155th Street Viaduct, New York City, New York". Scientific American (v. 62–63). Munn & Company: 385. 1890. Archived from the original on June 28, 2022. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g Landmarks Preservation Commission 1992, p. 13.

- ^ a b c d "The Central Bridge and St. Nicholas Viaduct" (PDF). The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. 50 (1286): 572–573. November 5, 1892. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2020 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ a b "The Macomb's Dam Bridge Improvement" (PDF). The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. 49 (1258): 641–644. April 23, 1892. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2020 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "They Want the Viaduct.; Washington Heights Taxpayers Argue for the Improvement". The New York Times. August 22, 1889. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 17, 2018. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Bridge Approach Opened by Walker; Ceremony at Macomb's Dam Span Also Marks Harlem Lane Park's Improvement". The New York Times. December 20, 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 28, 2022. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ a b Gay 1905, p. 71.

- ^ Annual Report of the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society to the Legislature of the State of New York. Assembly document. The Society. 1918. p. 142. Archived from the original on June 28, 2022. Retrieved January 4, 2020.

- ^ Morris, L.G. (1857). Harlaem River: its use previous to and since the Revolutionary War, and suggestions relative to present contemplated improvement. Printed by J. D. Torrey. pp. 10–16. Archived from the original on June 28, 2022. Retrieved January 4, 2020.

- ^ Joyce, Joseph Asbury; Joyce, Howard Clifford, 1871–1932; Nuisances (1906). Treatise on the law governing nuisances. Albany, N.Y., M. Bender & co. pp. 116, 546.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Department of Parks; Bids for the Construction of the Central Bridge Opened the Lincoln Statue in Union Square Resignation of an Architect". The New York Times. March 4, 1875. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 4, 2020. Retrieved January 4, 2020.

- ^ "A Patchwork of Wood; the Crazy Structure Which Serves as Macomb's Dam Bridge". The New York Times. June 14, 1885. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 30, 2019. Retrieved January 4, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Landmarks Preservation Commission 1992, p. 3.

- ^ Scientific American. Munn & Company. 1890. p. 385. Archived from the original on June 28, 2022. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- ^ Laws of the State of New York passed at the sessions of the Legislature. Laws of New York. 1887. pp. 787–788. hdl:2027/uc1.b4375291.

- ^ United States Congress (1891). 51st Congress, Session I, Chapter 907 (Sept. 19, 1890) (PDF). Revised Statutes of the United States, Passed at the First Session of the Forty-third Congress, 1873–'74: Supplement to the Revised Statutes of the United States. ... Vol.1–2 1874/1891-1901. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 800. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 12, 2020. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- ^ "Low Bridges Wanted; Objections to the Proposed Harlem River Improvements". The New York Times. April 18, 1890. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 16, 2020. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ^ New York (N.Y.). Dept. of Public Works (1890). Report. p. 28. Archived from the original on June 28, 2022. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Landmarks Preservation Commission 1992, p. 4.

- ^ "A Street Built in Mid-Air; Work Begun Upon New-York's Wonderful Viaduct. Washington Heights to Be Connected with the Low Lands by a Driveway of Easy Descent by a Great Feat of Engineering". The New York Times. December 21, 1890. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 28, 2022. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ^ New York (N.Y.). Dept. of Public Works (1894). Report. pp. 16–17.

- ^ "They Fear Isolation; Annexed District Residents Don't Want Macomb's Dam Bridge Closed". The New York Times. May 15, 1892. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 28, 2022. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ^ a b c Gay 1905, p. 73.

- ^ "Moving the Draw Span of the Macomb's Dam Bridge, New York, New York". Engineering News-record (v. 28). McGraw-Hill Publishing Company: 152. 1892. Archived from the original on June 28, 2022. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ^ Triest, W. Gustav (1893). "The Substructure of the Seventh Avenue Swingbridge, New York City". Engineering News-record (v. 30). McGraw-Hill Publishing Company: 198–200. Archived from the original on June 28, 2022. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ^ "Board of Commissioners of the NYC Dept of Public Parks – Minutes and Documents: Minutes and Documents: May 4, 1892 – April 30, 1893" (PDF). New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. April 30, 1893. p. 223 (PDF p. 295). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 3, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- ^ "For A New City Park: Land Secured At The South End Of Macomb's Dam Bridge". New-York Tribune. November 29, 1893. p. 1. Archived from the original on June 28, 2022. Retrieved December 11, 2019 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "New York State Laws of 1893, Chapter 319". Minutes. New York (N.Y.). Board of Estimate and Apportionment. 1893. p. 803. Archived from the original on June 28, 2022. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ^ "Board of Commissioners of the NYC Dept of Public Parks – Minutes and Documents: May 2, 1894 – April 25, 1895" (PDF). New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. April 25, 1895. p. 120 (PDF p. 203). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 3, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- ^ "May Produce "Trilby" for the Present; Near Macomb's Dam Bridge Opened". The New York Times. May 2, 1895. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 30, 2019. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ^ "Union Railroad Wins; Trolley Tracks to be Built Over Macomb's Dam Bridge". The New York Times. September 9, 1903. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 28, 2022. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ "Car on Macomb's Dam Bridge; First Trolley Goes Across, Connecting with Eighth Avenue". The New York Times. October 2, 1904. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 28, 2022. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Landmarks Preservation Commission 1992, p. 8.

- ^ "Walker Opens Approach To Macomb's Dam Bridge". New York Herald-Tribune. December 20, 1930. p. 17. Archived from the original on June 28, 2022. Retrieved January 5, 2020 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Harlem Bridge Damaged; Drifting Lighter Rips Up 60 Feet of Macombs Dam Span". The New York Times. December 23, 1949. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 28, 2022. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ Ranzal, Edward (March 25, 1971). "Tolls on Harlem River Bridges Studied" (PDF). The New York Times. p. 41. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 28, 2022. Retrieved January 25, 2021.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Owen (March 25, 1971). "City Looks to Tolls on Harlem River". New York Daily News. p. 29. Archived from the original on February 1, 2021. Retrieved January 25, 2021 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ Dembart, Lee (June 16, 1977). "Broad Parking Ban in Manhattan Begins as Mayor Yields to Ruling" (PDF). The New York Times. p. 1. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 28, 2022. Retrieved January 25, 2021.

- ^ "New Bridge to Open Near Yankee Stadium". The New York Times. June 15, 1977. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 21, 2018. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ^ "17 Key Bridges With Structural Problems". The New York Times. April 18, 1988. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 7, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1992, p. 1.

- ^ Moritz, Owen (January 16, 1992). "Fabled link to another ERA". New York Daily News. p. 371. Archived from the original on June 28, 2022. Retrieved January 22, 2021 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ a b "New York City's Harlem River Bridges: The Reauthorization Of The Transportation Equity Act For The 21st Century" (PDF). New York City Department of Transportation. January 23, 2004. p. 9. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 16, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ Muller, Mike. "Preparing for the Great New York Earthquake". Gotham Gazette. Archived from the original on October 30, 2020. Retrieved January 8, 2020.

- ^ Abrahams, Michael J. (May 18, 2001). "Seismic Retrofit of Two New York City Bridges". Structures 2001. Washington, D.C., United States: American Society of Civil Engineers. pp. 1–12. doi:10.1061/40558(2001)41. ISBN 978-0-7844-0558-1.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1992, p. 7.

- ^ "The Harlem River: The Beginning of a Developing Movement in which the City May Take Pride" (PDF). The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. 55 (1423): 1039. June 22, 1895. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2020 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ a b Schuyler, Montgomery (October 1905). "New York Bridges" (PDF). Architectural Record. XVIII (4): 253–255. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (February 25, 1990). "Streetscapes: The University Heights Bridge; A Polite Swing to Renovation for a Landmark Span". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 25, 2015. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- ^ "New 145th Street Bridge Arrives in the City Via Barge". The New York Sun. November 1, 2006. Archived from the original on August 20, 2020. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- ^ Reier 2000, p. 87.

- ^ Annual Report For The Year Ended June 30, 1959. New York City Transit Authority. October 1959. p. 15.

Sources

- Gay, Martin; Municipal Engineers of the City of New York (1905). Proceedings of the Municipal Engineers of the City of New York. Harvard University. The Society. pp. 71–73.

- "Macomb's Dam Bridge" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. January 14, 1992. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 13, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- Reier, Sharon (2000). The Bridges of New York. New York City Series. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-41230-6. Archived from the original on March 4, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. NY-269, "Macombs Dam Bridge, Spanning Harlem River Between 155th Street Viaduct, Jerome Avenue, & East 162nd Street, Bronx, Bronx County, NY", 80 photos, 27 data pages, 11 photo caption pages

- Macombs Dam Bridge at Structurae

- 1893 establishments in New York (state)

- 1895 establishments in New York City

- Bridges completed in 1893

- Bridges completed in 1895

- Bridges in Manhattan

- Bridges in the Bronx

- Bridges over the Harlem River

- Concourse, Bronx

- Harlem

- Historic American Engineering Record in New York City

- New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan

- New York City Designated Landmarks in the Bronx

- Pedestrian bridges in New York City

- Road bridges in New York City

- Steel bridges in the United States

- Swing bridges in the United States