Cecil Vandepeer Clarke

Cecil Vandepeer Clarke | |

|---|---|

| Councillor for Putnoe | |

| In office ?–? | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 15 February 1897[1] |

| Died | 1961 (aged 63–64)[2] |

| Political party |

|

| Occupation | Engineer, businessman, soldier |

| Military career | |

| Nickname(s) | Nobby Clarke |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1914–1919; 1940–1945 |

| Battles / wars | World War I, World War II |

Major Cecil Vandepeer Clarke MC (1897–1961)[3] was an engineer, inventor and soldier who served in both the First and Second World Wars.

Early life

[edit]Clarke was born on 15 February 1897.[1] He grew up in London and was known to his friends as Nobby,[a] as he would be throughout his life.[1][4] He attended Greenwich Hospital School (now part of the National Maritime Museum) and the Grocers' Company School (later renamed Hackney Downs School). He studied at the University of London; but he abandoned this for a two-year certificate course with the Officer Training Corps when the First World War broke out in 1914.[1]

World War I

[edit]Clarke was gazetted as a Second Lieutenant in the Devonshire Regiment.[5] He then transferred to the 9th Battalion of the South Staffordshire Regiment with 23rd Division.[6] This unit was a Pioneer Battalion, whose duties involved tunnelling, and general explosives work. Clarke became an explosives expert and he was said to have loved making loud bangs.[6]

Clarke served with the British Expeditionary Force in France.[6] From October 1917 he served in Italy. He was awarded the Military Cross for his part in the Battle of Vittorio Veneto in 1918.[7]

Early personal life

[edit]In August 1928, Clarke married Dorothy Aileen Kendrick.[8] They had three children, John, David and Roger.[1][6]

Low Loading Trailer Company

[edit]Clarke moved to Bedford and became director of HP Webb and Co Ltd., a motor manufacturing firm. He registered patents relating to engine design.[9] In 1924 he bought a house in Tavistock Street, Bedford, together with an adjacent commercial garage; here he started his own engineering firm.[1] In his spare time he built his own design of car engine, but he found that it was not commercially viable because other manufacturers could make similar engines more economically.[1]

Clarke's brother ran a large farm and Clarke realised that there was a market for trailers of various types.[10] Clarke thought that existing two-wheeled trailers waggled about too much – particularly horse boxes.[10] He established the Low Loading Trailer Company Ltd. (LoLode for short) in Bedford. LoLode produced a wide range of trailers based on Clarke's design for a low-slung chassis and four close-coupled wheels with a stable suspension system.[10][b] LoLode became known for building caravans to customer requirements.[11] Standard features included Clarke's anti-rolling system with shock absorbers and hydraulic brakes.[11] On-board batteries, water tanks, petrol generators and other internal equipment attracted attention at shows.[11][12] Clarke's chassis and suspension design allowed passengers travelling in the caravan (which was permitted at that time[13]) at a speed of 40 mph (64 km/h) to pour drinks without spilling them,[4] and some LoLode caravans even featured a gimbal-mounted chemical toilet for use while travelling.[13]

After placing an advertisement in The Caravan & Trailer, he received a visit from the magazine's editor, Stuart Macrae. Macrae later recalled their first meeting:

Clarke at once fascinated me. He was a very large man with rather hesitant speech who at first struck me as being amiable but not outstandingly bright. The second part of this impression did not last long.[10]

Macrae was particularly impressed by Clarke's latest caravan. It was an enormous double-decked design; streamlined and futuristic, it included a toilet and a shower with hot and cold water.[10] Macrae wrote a piece about it in his magazine.[10]

In February 1940 the Low Loading Trailer Company contributed £6 18s to the Finland Fund at the time of Finland's Winter War conflict with the Soviet Union.[14]

Limpet mine

[edit]

In July 1939, Clarke was once again contacted by Macrae, who was by then the editor of Armchair Science, a popular magazine at the time. Macrae explained that he had been contacted by Major Millis Jefferis of the War Office, who had read a brief article in Armchair Science that described very powerful magnets.[16][17] Those particular magnets were not available, but following discussions it was clear what Jefferis had in mind and Macrae volunteered to design a new weapon that would magnetically adhere to ships below the water line. Now Macrae needed Clarke's experience and workshops.[18][19]

Macrae visited Clarke at home and after "sweeping a number of children out of the living room",[4] he laid out his rough drawings and the two men soon agreed to cooperate on the design of a new weapon.[20] Work began the next day. Clarke purchased some large tin bowls from a nearby branch of Woolworth's and a local tinsmith was engaged to make rims with annular grooves and plates which could be screwed on to close the rims.[4] Small horseshoe magnets were fixed in the grooves and with a filling of porridge in place of high explosive, the first prototypes were created.[21]

Clarke and Macrae took their prototype to Bedford Modern School baths, which were closed for such occasions.[18] Clarke was an excellent swimmer and was able to propel himself through the water with a prototype bomb attached to a keeper plate on webbing around his waist.[21] Clarke practised attaching the bomb to a metal griddle plate taken from the family kitchen that was used to simulate the hull of a ship.[22] At first, the magnetic adhesion to the keeper plate proved so great that it was difficult to remove the bomb, so the plate was made smaller to reduce the strength of its hold.[23] They also adjusted the bomb to have a slightly positive buoyancy, which was found to be advantageous.[23] Having developed the weapon thus far, it was duly named the limpet mine[23] after the marine sea creature – the limpet, a gastropod well known for its ability to adhere to rocks.

Clarke's son John later recalled:[24]

I remember going with my father in the motor boat and we trundled up and down the Ouse at different speeds with this underwater device, which nobody could see because it was under the water. And we demonstrated that the launch could travel up to 10 or 15 knots and the limpet mine was still firmly attached. So that was yet another test that my father had to undergo and it was all extremely interesting and exciting.

The next step was to design a delay mechanism so that when a limpet mine had been put in place, the bomber would have plenty of time to get away before the explosion.[23] A spring-loaded striker was designed which would be held back by a pellet that would slowly dissolve in water.[25] Finding a suitable substance for the pellet was difficult and expert advice was called in, but failed to find an answer: the time taken for the tested materials to dissolve was too variable.[25] The problem was solved when aniseed balls belonging to one of Clarke's children were tried.[25][26] The manufacturers, Barratt, could not supply the balls with the necessary holes, so Macrae resorted to drilling them through.[25] The delay device had to be protected from water until the limpet mine was actually in position and for this the delay device would be stored in a condom until it was deployed.[25]

The first few hundred limpet mines were produced at Clarke's workshop.[27] Soon the job went to outside contractors and over half a million limpets were made and issued for use.[27]

When the limpet mine work was over, there was time for a family holiday in Clarke's double-decker caravan. By the time the family returned, the Second World War had started.[18]

Underground tank

[edit]My dear sir

I was glad to have your letter of April 11th, and have read it with interest.

As Professor Lindemann told you in the strictest confidence, experiments are in hand on somewhat similar lines and as soon as results are available, so that we can tell whether your ideas can be applied, you will be informed. A great deal depends upon the type of soil and the conditions in which the machine will have to be used, but, in certain circumstances, which may well occur, the method you propose might be applicable.

The first rough experiments will tell us whether this line of development is promising, but until they have been carried out, it is difficult for us to go any further. I am hoping that it will not be a very long time before we are able to communicate with you again.

Yours v. truly,

Winston S. Churchill

–Letter from Churchill to Clarke[28]

When production of the limpet mine was under way, Clarke started work on a radical and ambitious project. Drawing on his experiences of trench warfare in the First World War and his particular expertise in tunnelling and explosives, he drew up a proposal for an armoured trench-forming machine.[29] Although the war had started, there was little real fighting on the Western Front and this period became known as the Phoney War. However, Clarke reasoned that eventually Germany's much vaunted Siegfried Line must be attacked.[29] His trench-forming machine would drive through the earth advancing 2,000 yards in a single night, men and tanks following in its wake in the relative safety of the trench it had formed.[29]

Clarke's machine would use a hydraulic ram to insert cylinders of ammonal explosive about 6 feet (1.8 m) underground.[28] After detonation, the machine would advance into the crater it had just created and repeat the process.[28] The machine would be protected by 6 inches (150 mm) of armoured plate at the front to protect it from its own explosions with the same at the top and rear as a defence against enemy fire.[28] Clarke wrote "I envisaged a machine that would by hydraulic means more or less row itself through the ground."[28] The machine's trench would be about 6 by 4 feet (1.8 by 1.2 m).[28][c]

Clarke's proposal was sent first to the Royal Engineer and Signals Board at the Ministry of Supply. Clarke requested that all communication be passed through Jefferis. The Ministry turned down Clarke's ideas with a standard letter of rejection.[31]

A few weeks later, Clarke tried again. This time he sent his plans directly to Winston Churchill, who was at the time First Lord of the Admiralty.[31] Churchill's chief scientific advisor, Frederick Lindemann, contacted Clarke by telegram to request an immediate interview.[31][28] Lindemann was impressed by Clarke and his ideas.[31][28]

Churchill already had a trenching machine in development at the Naval Land Section at the Ministry of Supply; it was known by its code name Cultivator No. 6. The Cultivator worked by purely mechanical means and was by this time in an advanced state. Clarke's idea was simpler and it would be able to clear landmines and other obstacles in its path.[28] It would even be able to deal with blockhouses by placing multiple charges underneath them before blowing them up.[28] The main disadvantage of Clarke's trenching machine was that at an estimated speed of 250 yards (230 m) per hour[28] it was much slower than Cultivator's 0.42 or 0.67 miles (680 or 1,080 m) per hour.[32]

Clarke was made an assistant director in the Naval Land Section at the generous salary of £1,000 per annum (equivalent to £53,000 in 2019[33]).[31][28]

Clarke came to hate his Admiralty job.[34] With the fall of France, it was evident that entrenching machines like Cultivator were not going to be needed soon and probably never would be. Clarke resigned from the project and made his availability known to the War Office; he was soon called up for military service.[35]

Aston House

[edit]

While he was still on the Admiralty payroll, Clarke was called upon to make some design improvements to the limpet mine.[35] The mine was being manufactured by the Special Operations Executive (SOE) at their Technical Research and Development Station at Aston House near Stevenage, Hertfordshire,[35] and there were some problems with the original model to be ironed out.[36]

Aston House was a large, secluded country house surrounded by 5 acres (2.0 hectares) of parkland.[35] The house had been acquired by the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) in 1939. The SIS, a secret branch of the Foreign Office, then handed the house over to SOE for whom it became known as Station XII.[35] Aston House was used to produce and package special weapons and to train SOE agents in their use.[37] The station had a high wire fence and many security measures. When Clarke first arrived at Aston House he was kept waiting at a guard post, but after a few minutes he slipped past the security measures and got into the house and into the presence of the station's commandant, Arthur Langley.[38][36] Langley did not take kindly to his initiative and forbade Clarke to enter the house or to be served with meals – this continued until Langley was replaced some months later by Captain Leslie John Cardew-Wood (generally known as John Wood).[38][36][39]

A wide range of munitions, including the limpet mine and the spigot gun, were produced at Aston House. Significant development work went on including some early work on shaped charges.[40]

Having resigned from his job at the Admiralty, Clarke joined the Army and was taken on by Wood to work at Aston House, where he was put in charge of training SOE saboteurs.[40]

Spigot gun

[edit]

Clarke developed a weapon that he called the spigot gun.[30][42] It was a type of spigot mortar that propelled a projectile consisting of a bomb about 5 in (130 mm) in diameter containing 3 lb (1.4 kg) of high explosives and a finless tail tube containing a propelling charge similar to a shotgun cartridge.[43] This was placed over the spigot and when the propelling charge was fired, the projectile would fly off; this sudden acceleration also armed the contact detonator.[44] As soon as the projectile had left the spigot, a plug would block the tail tube, greatly reducing the flash and noise of the discharge.[44] The bomb had a thin front that collapsed when it struck a target, thereby placing the explosive in intimate contact with the target immediately prior to detonation; the bomb could penetrate up to 50 mm of armour.[44] Simple, quiet, and easily portable, the spigot gun was an ideal weapon for the saboteur and it was thought very suitable for jungle warfare.[44]

The most widely used version of the spigot gun was the 'tree spigot gun'. This had its spigot mounted on a ball and socket joint attached to a large wood screw. A pair of handles were provided to turn the screw so that it could be secured in a tree or other suitable wooden support; one of the handles had a chisel-shaped end for removing bark from trees. When this had been done, a sighting tool could be placed on the spigot, and the spigot was then adjusted and clamped into position. The sight was then removed and replaced with the mortar projectile.[44][41] The weapon was fired by pulling on a lanyard, by a trip wire as part of a booby trap, or by a pencil detonator delay mechanism.[44] The tree spigot had a range of 200 yards (180 m). As part of a booby trap, it could be positioned to fire downwards onto the relatively thin armour on top of a tank.[41] One account of its use describes a trip wire for a locomotive; placed up high it was likely to be missed by track walkers looking for bombs on the railway line.[45][46]

A variant form was the 'plate spigot gun'. This screwed into a tree but was also equipped with a 0.3 in (7.6 mm) steel plate that served as a gun shield. This version had a maximum range of 150 yards (140 m) and could engage moving targets at up to 100 yards (90 m).[44]

Another variant was the 'ground spigot gun'. The weapon was equipped with a small visored plate measuring about 2 square feet (0.19 m2) that served as a gun shield. The 'gun' was supported by a tubular structure with canvas stretched between two trailing tubular legs; this provided support for the gunner lying prone and the combination of the supporting structure and the gunner's weight helped to absorb the recoil.[44] This version had a maximum range of 150 yards (140 m) and could engage moving targets at up to 100 yards (90 m).[44]

The tree and plate spigot weapons were taken up by the War Office for use by the Home Guard.[42] The tree spigot was used by SOE agents and resistance fighters, for whom it was available in pre-packed cases for dropping by parachute.[47] A special rucksack was available to carry a tree spigot and three bombs.[48] The tree spigot was purchased in large numbers by the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS).[42][49]

Brickendonbury Manor

[edit]In December 1940, Clarke was promoted to Captain (acting Major) and appointed as the commandant of Brichendonbury Manor, SOE's Station XVII.[50][8] He was responsible for the training of SOE agents in sabotage before they went into action.[51]

Clarke was keen to give his recruits training experiences that were as realistic as possible.[51] In an example later recalled by his son, he took his team out one dark night and using scaling ladders they got past the guards and into Luton Power Station. There they planted dummy bombs on the transformers before retreating over the perimeter walls without being noticed. A little later, Clarke, with a pass stating that he, Major CV Clarke, had authority to inspect Luton Power Station – a document he had himself created – walked up to the front door and asked for the Officer of the Guard. He insisted on doing a routine inspection there and then. Clarke soon located the dummy charges and said to the distraught officer in charge of the guard, "Alright old man, you say nothing about this and I'll say nothing about it. But you've learnt your lesson." The decoys were retrieved and the unconventional training operation was over.[52][53]

So that he could experience the full range of training of an SOE agent, Clarke was sent for parachute training.[54] On 8 July 1941, Clarke sustained a bone fracture resulting from a heavy landing while making a jump at No. 1 Parachute Training School RAF at Tatton Park.[8]

Operation Josephine B

[edit]Clarke trained three agents who were to be parachuted into Bordeaux on the night of 11–12 May 1942 for Operation Josephine B (also known as Operation Josephine).[55][53] The agents were French and replaced a party of Poles who had been badly injured in an aeroplane crash. The agents took with them the smaller, shaped-charge limpets.[56] After reconnoitring their target, the Pessac transformer station, the agents were put off by the difficulty of getting past the guards, the nine-foot-high wall and a high-tension wire.[55] They then failed to make their rendezvous with the submarine sent to pick them up. Instead the raiders lay low for a month and then made their attack with special equipment to climb over the walls and open the main gate. Six of the eight transformers were destroyed – the charges having slipped from two of the transformers before exploding – and the party escaped.[55][57]

It took a long time for the Germans to recover from the disruption caused. The nearby U-boat docks were put out of action for months, 250 people were arrested, the Pessac area was fined one million French Francs and 12 German guards were shot.[55] The attack was SOE's first successful industrial sabotage attack in France.[57]

Operation Anthropoid

[edit]Operation Anthropoid was the code name for the assassination attempt on SS-Obergruppenführer and General der Polizei Reinhard Heydrich, the Nazi Germany acting Reichsprotektor of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. The operation was prepared by the SOE.[58]

Clarke and Wood designed a grenade from a modified No. 73 Grenade,[59] a weapon also known as the Thermos bomb from the resemblance to a Thermos flask.[60] A standard No. 73 grenade was approximately 3.5 inches (89 mm) in diameter and 11 inches (280 mm) in length, and weighed some 4.5 pounds (2.0 kg). It was fitted with a No. 69 "All-ways" fuse that would detonate the bomb regardless of the way it fell. However, the grenade's considerable weight meant that it could only be thrown short distances.[60]

The modified grenade was made from the top third of the standard device. This reduced the weight to just over 1 pound (0.45 kg), making it much easier to throw and to conceal.[59] At Aston House, Clarke and Wood trained Czechoslovak soldiers Jozef Gabčík and Jan Kubiš to throw the bombs into a slow-moving vehicle by using an old Austin rolled down a ramp.[59] Others then took over the training using a car fitted with armour plates.[59] The two Czechoslovak soldiers were airlifted along with seven other soldiers from Czechoslovakia's army-in-exile in the United Kingdom.[61] They were sent with an arsenal of guns, grenades, explosives, and other equipment including a tree spigot gun so that they could take advantage of whatever situation presented itself.[59]

The attack was carried out in Prague on 27 May 1942. The assassination attempt did not go smoothly; Gabčík's sten gun jammed and Kubiš' grenade fell short. The assassins fled, convinced that they had failed. However, although seemingly only slightly wounded at the time, Heydrich died in hospital just over a week later. The assassins were tracked down and killed in a manhunt and the Germans carried out brutal reprisals against the civilian population.[59]

Other operations

[edit]Clarke was also involved in the training of agents who went on to attack ships of the French Fleet at Oran in Algeria in November 1942,[62] and in 1943 the agents of Operation Gunnerside which destroyed the heavy water plant at Rjukan, Vemork, in Norway[62] – an operation later evaluated by SOE as the most successful act of sabotage in all of World War II.[63] Clarke also trained an SOE agent Harry Rée for his activities in occupied France.[62]

MD1

[edit]In February 1942, Clarke requested a transfer to MD1.[64] The exact circumstances of his transfer are unclear; it seem that his unconventional training methods – breaking into RAF and transformer stations – had made him unpopular. Colin Gubbins liked Clarke, but thought he might be of more use elsewhere and approached Stuart Macrae.[51]

Macrae was now working for MD1, a small organisation for the development of weapons directly under the patronage of the prime minister, Winston Churchill run by Major Millis Jefferis

Altimeter switch

[edit]At MD1, Clarke was able to complete the development of a sabotage device on which he had been working. It was designed to be put on board an aircraft and to explode when a certain altitude was reached.[30][65] The saboteur would need to place the device on board, and this could conveniently be done by slipping a device through one of any number of small holes that were typically present on aircraft of the time or through a small slit cut in the outer fabric. To make this as easy as possible, the device was designed as a long, thin, flexible 'sausage' of explosive.[65] Clarke considered that a saboteur should carry the device hidden in the legs of trousers. Despite the inevitable ribaldry, this was the method he taught to his students.[65]

The detonating mechanism was known as the 'altimeter switch' or 'aero switch'.[65]

The altimeter switch was extensively used by the OSS, who distributed it to Chinese forces, especially those in Chungking,[66] where it was used to assassinate Dai Li, the widely hated head of the Kuomintang (KMT) secret police.[66]

The Great Eastern

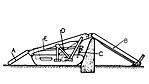

[edit]| Churchill Great Eastern Ramp | |

|---|---|

Churchill Great Eastern Ramp. From top left: three-quarters view, deployed in anti-tank ditch, over wall and against sea wall. Key: (A) Rear ramp, (B) Projected ramp, (C) Front sprag, (D) Distance indicator, (E) Fixed ramp.[67] |

In the winter of 1943, Clarke had himself sent to various weapon training schools in North Africa, Egypt, Palestine and Italy to demonstrate MD1's PIAT anti-tank weapon and various new fuses. In Italy he soon fell out with the local representative of the Director of Artillery. Disgruntled and dejected, he returned to his home in Bedford without telling anybody where he was and came close to having to face a court-martial for desertion.[68]

Settling back into MD1, he thought up the idea of a rocket-operated tank bridge.[68] Other tank-mounted bridges used hydraulics or winch mechanisms to deploy a portable bridge; the existing Churchill ARK was a tank chassis with ramps either side to make a bridge of itself. Churchill AVRE's could push a 150 ft Bailey Bridge over a 80 ft gap. Clarke's bridge tank was designed to overcome much bigger obstacles than could be bridged by the Churchill ARK, both horizontally and vertically. It was able to form a bridge 60 feet (18 m) long and could cross a wall 12 feet (3.7 m) high and 5 feet (1.5 m) wide.[69]

MD1 had prospered as the war progressed and the department had little difficulty getting hold of two Churchill tanks and the large amount of steelwork required.[68] On the first live test the rockets were so powerful that they nearly pulled the tank along with the flying ramp, as a result of which the driver was "not in good shape", but Clarke persisted with the trial and the viability of the design was confirmed.[68]

The "Great Eastern", as the vehicle would become known, was powered by two groups of 3-inch (76 mm) rockets. The idea was that on reaching a canal, wall or other obstacle the tank would stop. Then a distance-measuring device could be extended by the crew turning a windlass so that the correct position of the vehicle could be gauged.[70] When in position, the rockets were fired, causing the ramps to unfold and be thrown over the obstacle. Within 30 seconds,[71] vehicles could then pass up a smaller ramp to the rear, over the bridging tank itself and then over the long unfolded ramp.[68][72]

Recovering the vehicle took longer and required an A-frame to be put up and a series of manoeuvres to refold the ramps.[73] The sprags were repositioned manually with a special tool.[74] The projected ramp landed on concertina shock absorbers that were liable to be crushed if the ramp landed on anything other than soft ground; damaged shock absorbers had to be replaced.[74] Spare rockets were held in a magazine at the rear of the vehicle.[75] Without deploying its projected ramp, the Great Eastern could be used to bridge gaps of up to 40 feet (12 m) such as an anti-tank ditch with a vertical retaining wall.[76]

Ten Great Easterns were completed and Clarke went with them to France after the invasion of France in June 1944.[77] Clarke trained the Canadians in the 21st Army Group, who were then advancing into the Netherlands, where it was hoped they would be of use crossing canals.[71] Clarke's son later recorded: "To my father's private disgust and disappointment, it was ready and planned to carry out an operation at the end of April 1945 when the Germans put their hands up in the Low Countries and the operation was therefore called off."[53] The Great Easterns never saw action.[77]

Other weapons

[edit]Clarke designed a type of jumping ammunition for a mortar,[78] a different sort of low air-burst mortar bomb,[78] and a self-propelled multiple mortar firing device for the new Black Prince tank.[78]

Later life

[edit]Clarke was released from the Army in November 1945.[2] He returned to Bedford and moved his family to a new home in the town.[2] He joined the Territorial Army as a captain, where he served for six years before being transferred to the Intelligence Corps.[2]

Clarke shared a number of awards from the Royal Commission on Awards to Inventors: in 1953 he received £400 [equivalent to £14,100 in 2024[79]] for the limpet mine, and shared £300 [£10,600] with Stuart Macrae and Charles Neville Wilson for the altimeter switch.[15]

Clarke organised the Bedford branch of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, and was an elder of the Presbyterian church.[2] He worked as a Councillor for Putnoe. He was elected as a Labour Party candidate, and then after six years he joined the Liberal Party in 1959 – possibly over issues relating to nuclear weapons.[2]

At the age of 60, shortly after retiring as a Major, Clarke suffered a nonfatal heart attack. He died in 1961.[2]

See also

[edit]- British anti-invasion preparations of the Second World War

- British hardened field defences of World War II

References

[edit]- Footnotes

- ^ Nobby is a nickname commonly used in English for those with the surname Clark or Clarke

- ^ "Advertisement for LoLode trailers". Grace's Guide. May 1951 [approx.] Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ^ Clarke's son John gave a slightly different description of the machine from his recollections from boyhood.[30]

- Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g O'Connor 2010, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f g O'Connor 2010, p. 59.

- ^ O'Connor 2010, pp. 5, 59.

- ^ a b c d Macrae 1971, p. 8.

- ^ "No. 29187". The London Gazette. 9 June 1915. pp. 5607–5608.

- ^ a b c d O'Connor 2010, p. 6.

- ^ "Honours and Distinctions M.C." University of London Officers Training Corps, roll of war service, 1914-1919 (1921). p. 108. Retrieved 25 July 2011.

For distinguished service in connection with military operations in Italy. Gazette, 3 June 1919.

- ^ a b c HS 9/321/8.

- ^ Cecil Vandapeer Clarke (14 May 1919). "Improved mechanism for converting reciprocating motion into rotary motion". Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Macrae 1971, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Jenkinson 2003, p. 43.

- ^ "Conveying Horses By Road". The Times. 12 March 1936. p. 19 column c. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ a b Pippin, p. 2.

- ^ The Finland Fund. The Times, 6 February 1940 p.3.

- ^ a b T 166/40.

- ^ Macrae 1971, p. 1.

- ^ Unattributed. World's Most Powerful Magnet. Armchair Science July 1939 p. 70.

- ^ a b c Clarke 2005b.

- ^ National Archive. T 166 – Hearing 16 November 1953 – Macrae. Document 328.

- ^ National Archive. T 166-21 Awards to Inventors – Macrae and others.

- ^ a b Macrae 1971, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Bunker 2007, p. 155.

- ^ a b c d Macrae 1971, p. 9.

- ^ Clarke 2005a.

- ^ a b c d e Macrae 1971, p. 10.

- ^ Unattributed. Limpet Bomb Claim By Inventors – Use of Aniseed Balls. The Times 17 November 1953 p. 4 column F.

- ^ a b Macrae 1971, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l PREM 3/320/1.

- ^ a b c Bunker 2007, p. 159.

- ^ a b c Clarke 2005d.

- ^ a b c d e Bunker 2007, p. 160.

- ^ Turner 1988, p. 73.

- ^ United Kingdom Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the MeasuringWorth "consistent series" supplied in Thomas, Ryland; Williamson, Samuel H. (2024). "What Was the U.K. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ Macrae 1971, p. 48.

- ^ a b c d e O'Connor 2010, p. 30.

- ^ a b c Macrae 1971, p. 94.

- ^ Richard Norton-Taylor (26 October 1999). "How exploding rats went down a bomb – and helped British boffins win the second world war". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ a b O'Connor 2010, p. 33.

- ^ "Leslie John Cardew-Wood (1898-1990)". The Links Club. Retrieved 27 October 2013.

- ^ a b Turner 2011, p. 131.

- ^ a b c The Spigot Gun 1943.

- ^ a b c O'Connor 2010, pp. 34–36.

- ^ HS 7/28; Seaman 2001, pp. 86–94

- ^ a b c d e f g h i New British Spigot Guns 1943.

- ^ Lovell 1963, p. 178.

- ^ Lovell 1964, pp. 45–46.

- ^ HS 7/28; Seaman 2001, pp. 86–94

- ^ HS 7/28; Seaman 2001, pp. 86–94

- ^ Miscellaneous Weapons 1946, pp. 28–32.

- ^ O'Connor 2010, p. 36.

- ^ a b c Macrae 1971, p. 195.

- ^ O'Connor 2010, pp. 43–44.

- ^ a b c Clarke 2005e.

- ^ O'Connor 2010, p. 44.

- ^ a b c d O'Connor 2010, p. 45.

- ^ Clarke 2005g.

- ^ a b Richards 2004, p. 110.

- ^ Burian et al. 2002, p. 37.

- ^ a b c d e f Turner 2011, pp. 106–109.

- ^ a b Mackenzie1995, p. 92.

- ^ Turner 2011, pp. 106–107.

- ^ a b c O'Connor 2010, p. 47.

- ^ Foot 1984, p. 211.

- ^ O'Connor 2010, p. 49.

- ^ a b c d Macrae 1971, p. 155-156.

- ^ a b Lovell 1964, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Service Instruction Book, GE Ramp 1945.

- ^ a b c d e Macrae 1971, p. 196.

- ^ Bob Grimster. "Churchill Great Eastern Ramp". Armour in Focus. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ Service Instruction Book, GE Ramp 1945, p. 13.

- ^ a b O'Connor 2010, p. 58.

- ^ Delaforce 1998, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Service Instruction Book, GE Ramp 1945, p. 21.

- ^ a b Service Instruction Book, GE Ramp 1945, p. 26.

- ^ Service Instruction Book, GE Ramp 1945, p. 17.

- ^ Service Instruction Book, GE Ramp 1945, p. 9.

- ^ a b Macrae 1971, p. 197.

- ^ a b c O'Connor 2010, p. 56.

- ^ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- Published documents

- Bunker, Stephen (2007). Joanne Moore (ed.). Spy Capital of Britain: Bedfordshire's Secret War 1939-1945. Bedford Chronicles Press. ISBN 978-0906020036.

- Burian, Michal; Knížek, Aleš; Rajlich, Jiří; Stehlík, Eduard (2002). "Assassination – Operation Anthropoid – 1941–1942" (PDF). Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- Clarke, John Vandepeer (2005a). "Aniseed Balls and the Limpet Mine". WW2 People's War. BBC. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- Clarke, John Vandepeer (2005b). "Wartime memories of my childhood in Bedford Part 1". WW2 People's War. BBC. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- Clarke, John Vandepeer (2005c). "Wartime memories of my childhood in Bedford Part 2". WW2 People's War. BBC. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- Clarke, John Vandepeer (2005d). "Wartime memories of my childhood in Bedford Part 3". WW2 People's War. BBC. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- Clarke, John Vandepeer (2005e). "Wartime memories of my childhood in Bedford Part 4". WW2 People's War. BBC. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- Clarke, John Vandepeer (2005f). "Secret Station 17 – Special Operations – Sabotage". WW2 People's War. BBC. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- Clarke, John Vandepeer (2005g). "Operation Josephine – a successful SOE operation carried out under Major Clarke". WW2 People's War. BBC. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- Delaforce, Patrick (1998). Churchill's Secret Weapons – The Story of Hobart's Funnies. Robert Hale. ISBN 0-7090-6237-0.

- Foot, M.R.D. (1984). The Special Operations Executive 1940-1946. BBC Books. ISBN 0-563-20193-2.

- Jenkinson, Andrew (2003). Caravans: The Illustrated History 1919-1959. Veloce Publishing. ISBN 978-1903706824.

- Lovell, Stanley P (July 1963). "Deadly Gadgets of the OSS". Popular Science. 183 (1): 56–59, 178–180.

- Lovell, Stanley P (1964). Of spies & stratagems. Pocket Books. ASIN B0007ESKHE.

- Mackenzie, S.P. (1995). The Home Guard: A Military and Political History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198205775.

- Macrae, Stuart (1971). Winston Churchill's Toyshop. Roundwood Press. SBN 900093-22-6.

- O'Connor, Bernard (2010). 'Nobby' Clarke: Churchill's Backroom Boy. Lulu. ISBN 978-1-4478-3101-3.

- Pippin, Shirley. "To Be Read at Your Convenience" (PDF). Historic Caravan Club. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- Richards, Brooks (2004). Secret Flotillas: Clandestine sea operations to Brittany, 1940-1944. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780714653167.

- Seaman, Mark (2001). Secret Agent's Handbook. First Lyons Press. ISBN 1-58574-286-4. – The bulk of this book is a reprint of National Archives documents HS 7/28 and HS 7/28.

- Turner, Des (2011). SOE's Secret Weapons Centre: Station 12. The History Press Ltd. ISBN 978-0752459448.

- Turner, John T (1988). 'Nellie' The History of Churchill's Lincoln-Built Trenching Machine. Occasional Papers in Lincolnshire History and Archaeology. Vol. 7. ISBN 0-904680-68-1.

- National Archive documents

- "PREM 3/320/1: NLE Mr. C. V. Clarke's invention". The Catalogue. The National Archives.

- "T 166/40: Awards to Inventors, CV Clarke, supplementary evidence". The Catalogue. The National Archives.

- "HS 7/28: Descriptive catalogue of special devices and supplies". The Catalogue. The National Archives.

- "HS 9/321/8: Cecil Vandepeer Clarke, SOE personnel file". The Catalogue. The National Archives.

- "New British Spigot Guns". Military Report on the United Nations. Military Intelligence Service – War Department. 15 July 1943. pp. 45–47. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- "Miscellaneous Weapons". Summary Technical Report of National Defence Research Committee. 1946. pp. 28–32. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- Service Instruction Book for Churchill (GE) Ramp. Chillwell Catalogue 62/665. The Chief Inspector of Fighting Vehicles.

- Film

- The Spigot Gun. Office of Strategic Services. 1943. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- The Spigot Gun (alternative version of OSS film) on YouTube

Further reading

[edit]- Foot, M.R.D. (1966). SOE in France. HMSO.

- Milton, Giles (2016). The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare. John Murray. ISBN 978-1-444-79895-1.

External links

[edit]- "Bomb, Spigot, Gun, 3 lbs. H.E." Mines and Charges of the SOE. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- "Limpet – placing rod, magnetic holdfast and AC delay". The Canvas Kayak Website. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- "Stuart Macrae's "Toy Box"". The Mills Grenade Collectors site. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- 1897 births

- 1961 deaths

- Military personnel from London

- Devonshire Regiment officers

- South Staffordshire Regiment officers

- Weapon designers

- British Army personnel of World War I

- British Army personnel of World War II

- British Special Operations Executive personnel

- Engineers from London

- People from Bedford

- 20th-century British inventors

- Labour Party (UK) councillors

- Liberal Democrats (UK) councillors

- Councillors in Bedfordshire

- 20th-century British politicians