Cayo Santiago

| |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Humacao, Puerto Rico |

| Coordinates | 18°9′23″N 65°44′3″W / 18.15639°N 65.73417°W |

| Area | 0.139179 km2 (0.053737 sq mi) |

| Length | 0.6 km (0.37 mi) |

| Width | 0.4 km (0.25 mi) |

| Highest elevation | 34.9 m (114.5 ft) |

| Highest point | El Morrillo or "Big Cay hill top" |

| Administration | |

| Commonwealth | Puerto Rico |

| Municipality | Humacao |

Cayo Santiago, also known as Santiago Island, Isla de los monos (or Island of the monkeys), is located at 18°09′23″N 65°44′03″W / 18.15639°N 65.73417°W, 0.59 mi (0.95 km) 0.6 mi (1.0 km) to the east of Punta Santiago, Humacao, Puerto Rico.[1][2] It is known as the home to approximately 1800 rhesus macaque monkeys, who have been observed and studied by scientists since 1938.

Geography

[edit]The island measures approximately 37.5 acres (15.2 ha), or 660 yards (600 m), north–south and 440 yards (400 m) east–west, including a "Small Key" which is connected to the main area ("Big Key") by a narrow, sandy isthmus. Six-hundred meters west of the southernmost point is a shoal, Bajo Evelyn, which has a shallow depth of 8 fathoms. While the island is flat to the north, it reaches a height of 114.5 ft (34.9 m), 1.8 mi (2.9 km) southwest of the island's port, on a small, rocky hill called El Morrillo, rising abruptly from the water and the surrounding lowlands. The area of the island is 0.054 sq mi (0.14 km2): Block 2000, Census Block Group 2, Census tract 1801, Humacao Municipio, Puerto Rico), of which the northeastern peninsula accounts for about 0.01 sq mi (0.03 km2).[3]

In the late 1940s, the island was expropriated by Puerto Rico from its private owners and ceded to the University of Puerto Rico. Only designated personnel and researchers are allowed on the island, although tourists can charter a boat to circle the island and view its primate inhabitants.[4]

Resident monkeys

[edit]Since December 1938, the island has been home to a free-ranging population of rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). Today's monkeys are direct descendants of the original population of 409 individuals.[5] Early individuals were imported from India, by Clarence Ray Carpenter,[1] and the School of Tropical Medicine, San Juan, that was operated by Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons and the University of Puerto Rico. Today, the colony—which numbers over one thousand macaques—serves as a research resource, supported by the National Institutes of Health and the University of Puerto Rico's Caribbean Primate Research Center. The island serves scientists, researchers and students from many institutions within the United States, and several in Europe. A pictorial history on the 75 years of the colony was recently published.[1]

Cayo Batata, a small island located 4 mi (6 km) to the southwest of Cayo Santiago, is under the jurisdiction of Humacao, and is also uninhabited by humans.

Changes in monkey behavior following a devastating hurricane

[edit]When Hurricane Maria caused widespread destruction throughout Puerto Rico in September, 2017, tiny Cayo Santiago was also devastated. About two-thirds of the vegetation on the island was killed, greatly reducing the shade available to the 1800 monkeys living there, who were in danger of heat related illness when exposed to direct sunlight on very hot days. Before the hurricane, the macaques had a very aggressive and competitive social structure, described as "despotic and nepotistic" by researchers. After the hurricane, researchers observed that their behavior was significantly less aggressive and that they were willing to share the limited shade, allowing other monkeys to sit much closer than previously, accepting unrelated monkeys instead of just their close family members. Monkeys would line up closely in the shadow of the trunk of a dead tree without the squabbling behavior common before the hurricane. A comparison of behavioral patterns in the five years before the hurricane with the behavior in the five years after the hurricane showed a significant reduction in aggression. Those monkeys that had larger than average social groups to cooperate with were 42% less likely to die.[6]

The research paper published in the journal Science reported that "We leveraged 10 years of data collected on rhesus macaques before and after a category 4 hurricane caused persistent deforestation, exacerbating monkeys’ exposure to intense heat. In response, macaques demonstrated persistently increased tolerance and decreased aggression toward other monkeys, facilitating access to scarce shade critical for thermoregulation. Social tolerance predicted individual survival after the hurricane, but not before it, revealing a shift in the adaptive function of sociality."[7]

Gallery

[edit]-

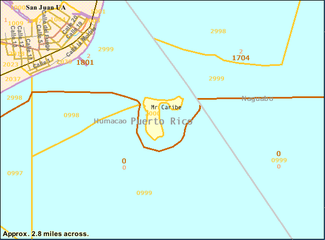

Nautical Chart of Cayo Santiago area

-

Census Bureau Map

-

Shy monkey at Cayo Santiago, Puerto Rico

-

A monkey walks on the beach of Cayo Santiago

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Kessler, Matthew J.; Rawlins, Richard G. (2016). "A 75‐year pictorial history of the Cayo Santiago rhesus monkey colony". American Journal of Primatology. 78 (1): 6–43. doi:10.1002/ajp.22381. ISSN 1098-2345. PMC 4567979. PMID 25764995.

- ^ Congress, The Library of. "LC Linked Data Service: Authorities and Vocabularies (Library of Congress)". id.loc.gov. Retrieved 2021-03-26.

- ^ "Puerto Rico and Virgin Islands NOAA Chart 25640" (PDF). NOAA. NOAA. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ "Monkey Island". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ The Cayo Santiago macaques : history, behavior, and biology. Richard G. Rawlins, Matt J. Kessler. Albany: State University of New York Press. 1986. ISBN 0-585-07492-5. OCLC 42855829.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Daniel, Ariel (July 10, 2024). "These monkeys were 'notoriously competitive' until Hurricane Maria wrecked their home". National Public Radio. Retrieved November 29, 2024.

- ^ Testrard, C.; Shergold, C.; Brent, L.J.N. (June 20, 2024). "Ecological disturbance alters the adaptive benefits of social ties". Science. 384 (6702): 1330–1335. doi:10.1126/science.adk0606. hdl:10871/136822. Retrieved November 29, 2024.