Causes of cancer pain

Cancer pain can be caused by pressure on, or chemical stimulation of, specialised pain-signalling nerve endings called nociceptors (nociceptive pain), or by damage or illness affecting nerve fibers themselves (neuropathic pain).[1]

Infection

[edit]Infection of a tumor or its surrounding tissue can cause rapidly escalating pain, but is sometimes overlooked as a possible cause. One study[2] found that infection was the cause of pain in four percent of nearly 300 cancer patients referred for pain relief. Another report[3] described seven patients, whose previously well-controlled pain escalated significantly over several days. Antibiotic treatment produced pain relief in all patients within three days.[4]

Tumor-related

[edit]Tumors can cause pain by crushing or infiltrating tissue, or by releasing chemicals that make nociceptors responsive to stimuli that are normally non-painful (cf. allodynia).

Vascular events

[edit]- Deep vein thrombosis

- Between 15 and 25 percent of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is caused by cancer (often by a tumor compressing a vein). Cancers most likely to cause DVT are pancreatic cancer, stomach cancer, brain tumors, advanced breast cancer and advanced pelvic tumors. DVT may be the first hint that cancer is present. It causes swelling and pain (which varies from intense to vague cramp or "heaviness") in the legs, especially the calf, and (rarely) in the arms.[5]

- Superior vena cava syndrome

- The superior vena cava (a large vein carrying circulating, de-oxygenated blood into the heart) may be compressed by a tumor, most often non-small-cell lung carcinoma (50 percent), small-cell lung carcinoma (25 percent), lymphoma, or metastasis, causing superior vena cava syndrome. Common symptoms include shortness of breath, swelling of the face and neck, dilation of veins in the neck and chest, and chest wall pain.[5][6]

Nervous system

[edit]Between 40 and 80 percent of patients with cancer pain experience neuropathic pain.[1]

Brain

- Brain tissue itself contains no nociceptors; brain tumors cause pain by pressing on blood vessels or the membrane that encapsulates the brain (the meninges), or indirectly by causing a build-up of fluid (edema) that may compress pain-sensitive tissue.[7]

Meninges

- Ten percent of patients with cancer spreading to different parts of the body develop meningeal carcinomatosis, where metastatic seedlings develop in the meninges (outer lining) of both the brain and spinal cord (with possible invasion of the brain or spinal cord). Melanoma and breast and lung cancer account for 90 percent of such cases. Back pain and headache – often severe and possibly associated with nausea, vomiting, neck rigidity and pain or discomfort in the eyes due to light exposure (photophobia) – are frequently the first symptoms of meningeal carcinomatosis. "Pins and needles" (paresthesia), bowel or bladder dysfunction and lower motor neuron weakness are common features.[8]

Spinal cord compression

- About three percent of cancer patients experience spinal cord compression, usually from expansion of the vertebral body or pedicle (fig. 1) due to metastasis, sometimes involving collapse of the vertebral body. Occasionally compression is caused by nonvertebral metastasis adjacent to the spinal cord. Compression of the long tracts of the cord itself produces funicular pain and compression of a spinal nerve root (fig. 5) produces radicular pain. Seventy percent of cases involve the thoracic, 20 percent the lumbar, and 10 percent the cervical spine; and about 20 percent of cases involve multiple sites of compression. The nature of the pain depends on the location of the compression.[4]

Nerve infiltration or compression

- Infiltration or compression of a nerve by a primary tumor causes peripheral neuropathy in one to five percent of cancer patients.[4]

Dorsal root ganglion inflammation

- Small-cell lung cancer and, less often, cancer of the breast, colon or ovary may produce inflammation of the dorsal root ganglia (fig. 5), precipitating burning, tingling pain in the extremities, with occasional "lightning" or lancinating pains.[4][9]

Brachial plexopathy

- Brachial plexopathy is a common product of Pancoast tumor, lymphoma and breast cancer, and can produce severe burning dysesthesic pain on the back of the hand, and cramping, crushing forearm pain.[4]

Bone

[edit]

Invasion of bone by cancer is the most common source of cancer pain. About 70 percent of breast and prostate cancer patients, and 40 percent of those with lung, kidney and thyroid cancers develop bone metastases. It is commonly felt as tenderness, with constant background pain and instances of spontaneous or movement-related exacerbation, and is frequently described as severe. Tumors in the marrow instigate a vigorous immune response which enhances pain sensitivity, and they release chemicals that stimulate nociceptors. As they grow, tumors compress, consume, infiltrate or cut off blood supply to body tissues, which can cause pain.[4][8]

Fracture

- Rib fractures, common in breast, prostate and other cancers with rib metastases, can cause brief severe pain on twisting the trunk, coughing, laughing, breathing deeply or moving between sitting and lying.[4] In breast, prostate or lung cancer, multiple myeloma and some other cancers, sudden onset limb or back pain may indicate pathological bone fracture (most often in the upper femur).[5]

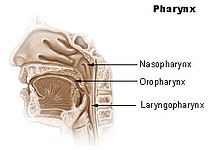

Skull

- The base of the skull may be affected by metastases from cancer of the bronchus, breast or prostate, or cancer may spread directly to this area from the nasopharynx (fig. 2), and this may cause headache, facial paresthesia, dysesthesia or pain, or cranial nerve dysfunction – the exact symptoms depend on the cranial nerves impacted.[4]

Pelvis

[edit]Pain produced by cancer within the pelvis varies depending on the affected tissue, but it frequently radiates diffusely to the upper thigh, and may refer to the lumbar region. Lumbosacral plexopathy is often caused by recurrence of cancer in the presacral space, and may refer to the external genitalia or perineum. Local recurrence of cancer attached to the side of the pelvic wall may cause pain in one of the iliac fossae. Pain on walking that confines the patient to bed indicates possible cancer adherence to or invasion of the iliacus muscle. Pain in the hypogastrium (between the navel and pubic bone) is often found in cancers of the uterus and bladder, and sometimes in colorectal cancer especially if infiltrating or attached to either uterus or bladder.[4]

Viscera

[edit]Visceral pain is diffuse and difficult to locate, and is often referred to more distant, usually superficial, sites.[8]

Liver

- Acute hemorrhage into a hepatocellular carcinoma causes severe upper right quadrant pain, and may be life-threatening, requiring emergency surgery or other emergency intervention.[5]

A tumor can expand the size of the liver several times and consequent stretching of its capsule can cause aching pain in the right hypochondrium. Other causes of pain in enlarged liver are traction of the supporting ligaments when standing or walking, the liver pressing against the rib cage or pinching the wall of the abdomen, and straining the lumbar spine. In some postures the liver may pinch the parietal peritoneum against the lower rib cage, producing sharp, transitory pain, relieved by changing position. The tumor may also infiltrate the liver's capsule, causing dull, and sometimes stabbing pain.[4]

Kidneys and spleen

- Cancer of the kidneys and spleen produces less pain than that caused by liver tumor – kidney tumors eliciting pain only once the organ has been almost totally destroyed and the cancer has invaded the surrounding tissue or adjacent pelvis. Pressure on the kidney or ureter from a tumor outside the kidney can cause extreme flank pain.[7] Local recurrence of cancer after the removal of a kidney can cause pain in the lumbar back, or L1 or L2 spinal nerve pain in the groin or upper thigh, accompanied by weakness and numbness of the iliopsoas muscle, exacerbated by activity.[4]

Abdominal and urogenital hollow organs

- Inflammation of artery walls and tissue adjacent to nerves is common in tumors of abdominal and urogenital hollow organs.[10] Infection or cancer may irritate the trigone of the urinary bladder, causing spasm of the detrusor urinae muscle (the muscle that squeezes urine from the urinary bladder), resulting in deep pain above the pubic bone, possibly referred to the tip of the penis, lasting from a few minutes to half an hour.[4]

Gastrointestinal

- The pain of intestinal tumors may be the result of disturbed motility, dilation, altered blood flow or ulceration. Malignant lymphomas of the gastrointestinal tract can produce large tumors with significant ulceration and bleeding.[10]

Respiratory system

- Cancer in the bronchial tree is usually painless,[10] but ear and facial pain on one side of the head has been reported in some patients. This pain is referred via the auricular branch of the vagus nerve.[4]

Fig. 3 The pancreas: 1. pancreatic head; 4. pancreatic body; 11. pancreatic tail

Pancreas

- Ten percent of patients with cancer of the pancreatic body or tail experience pain, whereas 90 percent of those with cancer of the pancreatic head will, especially if the tumor is near the hepatopancreatic ampulla. The pain appears on the left or right upper abdomen, is constant, and increases in intensity over time. It is in some cases relieved by leaning forward and heightened by lying on the stomach. Back pain may be present and, if intense, may spread left and right. Back pain may be referred from the pancreas, or may indicate the cancer has penetrated paraspinal muscle, or entered the retroperitoneum and paraaortic lymph nodes[4]

Rectum

- A local tumor in the rectum or recurrence involving the presacral plexus may cause pain normally associated with an urgent need to defecate. This pain may, rarely, return as phantom pain after surgical removal of the rectum, though pain within a few weeks of surgical removal of the rectum is usually neuropathic pain due to the surgery (described in one study[11] as spontaneous, intermittent, mild to moderate shooting and bursting, or tight and aching), and pain emerging after three months (described as deep, sharp, aching, intense, and continuous, made worse by sitting or pressure) usually signals recurrence of the disease. The emergence of pain on standing or walking (described as "dragging") may indicate a deeper recurrence involving attachment to muscle or fascia.[4]

Serous mucosa

[edit]Carcinosis of the peritoneum may cause pain through inflammation, disordered visceral motility, or pressure of the metastases on nerves. Once a tumor has penetrated or perforated hollow viscera, acute inflammation of the peritoneum appears, inducing severe abdominal pain. Pleural carcinomatosis is normally painless.[10]

Soft tissue

[edit]Invasion of soft tissue by a tumor can cause pain by inflammatory or mechanical stimulation of nociceptors, or destruction of mobile structures such as ligaments, tendons and skeletal muscles.[10]

Diagnostic procedures

[edit]

Some diagnostic procedures, such as venipuncture, paracentesis, and thoracentesis can be painful.[12]

Lumbar puncture

- In lumbar puncture a needle is inserted between two lumbar vertebrae, through the dura mater and arachnoid membrane surrounding the spinal cord, into the fluid-flled space between the arachnoid membrane and the spinal cord (the subarachnoid cavity), and cerebrospinal fluid (CFS) is withdrawn for examination. In one study, 14 percent of patients felt pain on lumbar puncture.[13] (fig. 5)

Post-dural-puncture headache

- In some patients, subsequent leakage of CSF through the dura mater puncture causes reduced CSF levels in the brain and spinal cord, leading to the development of post-dural-puncture headache (PDPH) hours or days later. Onset occurs within two days in 66 percent and within three days in ninety percent of PDPH cases. It occurs so rarely immediately after puncture that other possible causes should be investigated when it does.[14]

- The headache is severe and described as "searing and spreading like hot metal," involving the back and front of the head, and spreading to the neck and shoulders, sometimes involving neck stiffness. It is exacerbated by movement, and sitting or standing, and relieved to some degree by lying down. Nausea, vomiting, pain in arms and legs, hearing loss, tinnitus, vertigo, dizziness and paraesthesia of the scalp are common.[14]

Treatment-related

[edit]Potentially painful cancer treatments include immunotherapy which may produce joint or muscle pain; radiotherapy, which can cause skin reactions, enteritis, fibrosis, myelopathy, bone necrosis, neuropathy or plexopathy; chemotherapy, often associated with mucositis, joint pain, muscle pain, peripheral neuropathy and abdominal pain due to diarrhea or constipation; hormone therapy, which sometimes causes pain flares; targeted therapies, such as trastuzumab and rituximab, which can cause muscle, joint or chest pain; angiogenesis inhibitors like bevacizumab, known to sometimes cause bone pain; and surgery, which may produce post-operative pain, post-amputation pain or pelvic floor myalgia.

Chemotherapy

[edit]

Chemotherapy may cause mucositis, muscle pain, joint pain, abdominal pain caused by diarrhea or constipation, and peripheral neuropathy[12]

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy

- Between 30 and 40 percent of patients undergoing chemotherapy experience chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN): tingling numbness, intense pain, and hypersensitivity to cold, beginning in the hands and feet and sometimes progressing to the arms and legs.[15] Chemotherapy drugs associated with CIPN include thalidomide, the epothilones such as ixabepilone, the vinca alkaloids vincristine and vinblastine, the taxanes paclitaxel and docetaxel, the proteasome inhibitors such as bortezomib, and the platinum-based drugs cisplatin, oxaliplatin and carboplatin.[15][16][17] Whether CIPN arises, and to what degree, is determined by the choice of drug, duration of use, the total amount consumed and whether the patient already has peripheral neuropathy. Though the symptoms are mainly sensory – pain, tingling, numbness and temperature sensitivity – in some cases motor nerves are affected, and occasionally, also, the autonomic nervous system.[18]

- CIPN often follows the first chemotherapy dose and increases in severity as treatment continues, but this progression usually levels off at completion of treatment. The platinum-based drugs are the exception; with these drugs, sensation may continue to deteriorate for several months after the end of treatment.[19] Some CIPN appears to be irreversible.[19] Pain can often be helped with drug or other treatment but the numbness is usually resistant to treatment.[20] A 2007 American study found that most patients did not recall being told to expect CIPN, and doctors monitoring the condition rarely asked how it affects daily living but focused on practical effects such as dexterity and gait.[21]

Mucositis

- Cancer drugs can cause changes in the biochemistry of mucous membranes resulting in intense pain in the mouth, throat, nasal passages, and gastrointestinal tract. This pain can make talking, drinking, or eating difficult or impossible.[22]

Muscle and joint pain

- Withdrawal of steroid medication can cause joint pain and diffuse muscle pain accompanied by fatigue; these symptoms resolve with recommencement of steroid therapy. Chronic steroid therapy can result in aseptic necrosis of the humoral or femoral head, resulting in shoulder or knee pain described as dull and aching, and reduced movement in or inability to use arm or hip. Aromatase inhibitors can cause diffuse muscle and joint pain and stiffness, and may increase the likelihood of osteoporosis and consequent fractures.[22]

Radiotherapy

[edit]Radiotherapy may affect the connective tissue surrounding nerves, and may damage or kill white or gray matter in the brain or spinal cord.

Fibrosis around the brachial or lumbosacral plexus

- Radiotherapy may produce excessive growth of the fibrous tissue (fibrosis) around the brachial or lumbosacral plexui (clusters of nerves), which can result in damage to the nerves over time (6 months to 20 years). This nerve damage may cause numbness, "pins and needles" (dysesthesia) and weakness in the affected limb. If pain develops, it is described as diffuse, severe, burning pain, increasing over time, in part or all of the affected limb.[22]

Spinal cord damage

- If radiotherapy includes the spinal cord, changes may occur which do not become apparent until some time after treatment. "Early delayed radiation-induced myelopathy" can manifest from six weeks to six months after treatment; the usual symptom is a Lhermitte sign ("a brief, unpleasant sensation of numbness, tingling and often electric-like discharge going from the neck to the spine and extremities, triggered by neck flexion"), usually followed by improvement two to nine months after onset, though in some cases symptoms persist for a long time. "Late delayed radiation-induced myelopathy" may occur six months to ten years after treatment. The typical presentation is Brown-Séquard syndrome (movement problems and numbness to touch and vibration on one side of the body and loss of pain and temperature sensation on the other). Onset may be sudden but is usually progressive. Some patients improve and others deteriorate.[23]

Cited works

[edit]- Fitzgibbon, DR; Loeser, JD (2010). Cancer pain: Assessment, diagnosis and management. Philadelphia. ISBN 978-1-60831-089-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

References

[edit]- ^ a b Kurita GP, Ulrich A, Jensen TS, Werner MU, Sjøgren P (January 2012). "How is neuropathic cancer pain assessed in randomised controlled trials?". Pain. 153 (1): 13–17. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2011.08.013. PMID 21903329. S2CID 38733839.

- ^ Gonzalez GR, Foley KM, Portenoy RK (1989). "Evaluative skills necessary for a cancer pain consultant". American Pain Society Meeting, Phoenix Arizona.

- ^ Bruera E & MacDonald RN (1986). "Intractable pain in patients with advanced head and neck tumors: a possible role of local infection". Cancer Treatment Reports. 70 (5): 691–2. PMID 3708626.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Twycross R & Bennett M (2008). "Cancer pain syndromes". In Sykes N, Bennett MI & Yuan C-S (ed.). Clinical pain management: Cancer pain (2nd ed.). London: Hodder Arnold. pp. 27–37. ISBN 978-0-340-94007-5.

- ^ a b c d Koh, M; Portenoy, RK (2010). Bruera ED & Portenoy RK (ed.). Cancer Pain Syndromes. Cambridge University Press. pp. 53–85. ISBN 9780511640483.

- ^ Gundamraj NR; Richmeimer S (January 2010). "Chest Wall Pain". In Fishman, SM; Ballantyne, JC; Rathmell, JP (eds.). Bonica's Management of Pain. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1045–. ISBN 978-0-7817-6827-6. Archived from the original on 30 October 2023. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ a b Fitzgibbon & Loeser 2010, p. 34

- ^ a b c Urch CE & Suzuki R (2008). "Pathophysiology of somatic, visceral, and neuropathic cancer pain". In Sykes N, Bennett MI & Yuan C-S (ed.). Clinical pain management: Cancer pain (2nd ed.). London: Hodder Arnold. pp. 3–12. ISBN 978-0-340-94007-5.

- ^ Foley KM (2004). "Acute and chronic cancer pain syndromes". In Doyle D, Hanks G, Cherny N, Calman K (eds.). Oxford textbook of palliative medicine. Oxford: OUP. pp. 298–316. ISBN 0-19-851098-5.

- ^ a b c d e Fitzgibbon & Loeser 2010, p. 35

- ^ Boas RA, Schug SA & Acland RH (1993). "Perineal pain after rectal amputation: A 5 year follow up". Pain. 52 (1): 62–70. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(93)90115-6. PMID 8446438. S2CID 32239058.

- ^ a b International Association for the Study of Pain Archived 2011-09-28 at the Wayback Machine Treatment-Related Pain

- ^ Abraham JL (2005). A physician's guide to pain and symptom management in cancer patients (2 ed.). The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 108. ISBN 0801881013.

- ^ a b Turnbull GK, Shepherd DB (2003). "Post-dural puncture headache: pathogenesis, prevention and treatment". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 91 (5): 718–729. doi:10.1093/bja/aeg231. PMID 14570796.

- ^ a b del Pino BM (Feb 23, 2010). "Chemotherapy-induced Peripheral Neuropathy". NCI Cancer Bulletin. 7 (4): 6. Archived from the original on 2011-12-11. Retrieved 2014-06-19.

- ^ Grisold, Wolfgang; Oberndorfer, Stefan; Windebank, Anthony (2012). "Chemotherapy and Polyneuropathies" (PDF). NeuroOncology Magazine. 2 (1). THE EUROPEAN ASSOCIATION OF NEUROONCOLOGY: 25–36. ISSN 2224-3453. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 December 2019. Retrieved 3 July 2024.

- ^ "Herceptin and Peripheral sensory neuropathy, a phase IV clinical study of FDA data - eHealthMe". Archived from the original on 2016-10-09. Retrieved 2014-06-19.

- ^ Beijers AJ, Jongen JL, Vreugdenhil G (January 2012). "Chemotherapy-induced neurotoxicity: The value of neuroprotective strategies". The Netherlands Journal of Medicine. 70 (1): 18–25. PMID 22271810. Archived from the original on 2021-06-25. Retrieved 2021-06-25.

- ^ a b Windebank AJ & Grisold W (March 2008). "Chemotherapy-induced neuropathy". Journal of the Peripheral Nervous System. 13 (1): 27–46. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8027.2008.00156.x. PMID 18346229. S2CID 20411101.

- ^ Savage L (2007). "Chemotherapy-induced pain puzzles scientists". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 99 (14): 1070–1071. doi:10.1093/jnci/djm072. PMID 17623791. Archived from the original on 2015-03-19.

- ^ Paice JA, Ferrell B (2011). "The management of cancer pain". CA – A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 61 (3): 157–82. doi:10.3322/caac.20112. PMID 21543825.

- ^ a b c Fitzgibbon & Loeser 2010, p. 39

- ^ Fitzgibbon & Loeser 2010, pp. 102–3