Catherine de' Medici's building projects

The French queen Catherine de' Medici was patron for building projects including the Valois chapel at the Basilica of Saint-Denis, the Tuileries Palace, and the Hôtel de la Reine in Paris, and extensions to the Château de Chenonceau, near Blois. Born in 1519 in Florence, Catherine de' Medici was a daughter of both the Italian and the French Renaissance. She grew up in Florence and Rome under the wing of the Medici popes, Leo X and Clement VII. In 1533, at the age of fourteen, she left Italy and married Henry, the second son of King Francis I of France. On doing so, she entered the greatest Renaissance court in northern Europe.[1]

King Francis set his daughter-in-law an example of kingship and artistic patronage that she never forgot.[2] She witnessed his huge architectural schemes at Chambord and Fontainebleau. She saw Italian and French craftsmen at work together, forging the style that became known as the first School of Fontainebleau. Francis died in 1547, and Catherine became queen consort of France. But it wasn't until her husband King Henry's death in 1559, when she found herself at forty the effective ruler of France, that Catherine came into her own as a patron of architecture. Over the next three decades, she launched a series of costly building projects aimed at enhancing the grandeur of the monarchy. During the same period, however, religious civil war gripped the country and brought the prestige of the monarchy to a dangerously low ebb.[3]

Catherine loved to supervise each project personally.[4] The architects of the day dedicated books to her, knowing that she would read them.[5] Though she spent colossal sums on the building and embellishment of monuments and palaces, little remains of Catherine's investment today: one Doric column, a few fragments in the corner of the Tuileries Garden, an empty tomb at Saint-Denis. The sculptures she commissioned for the Valois chapel are lost, or scattered, often damaged or incomplete, in museums and churches. Catherine de' Medici's reputation as a sponsor of buildings rests instead on the designs and treatises of her architects. These testify to the vitality of French architecture under her patronage.

Influences

[edit]Historians often assume that Catherine's love for the arts stemmed from her Medici heritage.[1] "As the daughter of the Medici," suggests French art historian Jean-Pierre Babelon, "she was driven by a passion to build and a desire to leave great achievements behind her when she died."[6] Born in Florence in 1519, Catherine lived at the Medici palace, built by Cosimo de' Medici to designs by Michelozzo.[7] After moving to Rome in 1530, she lived, surrounded by classical and Renaissance treasures, at another Medici palace (now called the Palazzo Madama). There she watched the leading artists and architects of the day at work in the city.[8] When she later commissioned buildings herself, in France, Catherine often turned to Italian models. She based the Tuileries on the Pitti palace in Florence;[9] and she originally planned the Hôtel de la Reine with the Uffizi Palace in mind.[10]

Catherine, however, left Italy in 1533 at the age of fourteen and married Henry of Orléans, the second son of King Francis I of France. Though she kept in touch with her native Florence, her taste matured at the itinerant royal court of France.[1] Her father-in-law impressed Catherine deeply as an example of what a monarch should be.[11] She later copied Francis' policy of setting the grandeur of the dynasty in stone, whatever the cost. His lavish building projects inspired her own.[12]

Francis was a compulsive builder. He began extension works at the Louvre Palace,[13] He added a wing to the old castle at Blois, and built the vast château of Chambord, which he showed off to Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor in 1539. He also transformed the lodge at Fontainebleau into one of the great palaces of Europe, a project that continued under Henry II. Artists such as Rosso Fiorentino and Francesco Primaticcio worked on the interior, alongside French craftsmen.[14] This meeting of Italian Mannerism and French patronage bred an original style, later known as the first School of Fontainebleau.[15] Featuring frescoes and high-relief stucco in the shape of parchment or curled leather strapwork, it became the dominant decorative fashion in France in the second half of the sixteenth century.[16] Catherine later herself employed Primaticcio to design her Valois chapel. She also patronised French talent, such as the architects Philibert de l'Orme and Jean Bullant, and the sculptor Germain Pilon.[1]

The death of Henry II from jousting wounds in 1559 changed Catherine's life. From that day, she wore black and took as her emblem a broken lance.[18] She turned her widowhood into a political force that validated her authority during the reigns of her three weak sons.[19] She also became intent on immortalizing her sorrow at the death of her husband.[20] She had emblems of her love and grief carved into the stonework of her buildings.[20] She commissioned a magnificent tomb for Henry, as the centrepiece of an ambitious new chapel.

In 1562, a long poem by Nicolas Houël likened Catherine to Artemisia, who had built the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, as a tomb for her dead husband.[21] Artemesia had also acted as regent for her children. Houël laid stress on Artemesia's devotion to architecture. In his dedication to L'Histoire de la Royne Arthémise, he told Catherine:

You will find here the edifices, columns, and pyramids that she had built both at Rhodes and Halicarnassus, which will serve as remembrances for those who reflect on our times and who will be astounded at your own buildings–the palaces at the Tuileries, Montceaux, and Saint-Maur, and the infinity of others that you have constructed, built, and embellished with sculptures and beautiful paintings.[22]

Valois Chapel

[edit]

In memory of Henry II, Catherine decided to add a new chapel to the Basilica of Saint-Denis, where the kings of France were traditionally buried. As the centrepiece of this circular chapel, sometimes known as the Valois rotunda, she commissioned a magnificent and innovative tomb for Henry and herself. The design of this tomb should be understood in the context of its planned setting.[23] The plan was to integrate the tomb's effigies of the king and queen with other statues throughout the chapel, creating a vast spatial composition. Catherine's approval would have been essential for such a departure from funerary tradition.[24]

Architecture

[edit]To lead the Valois chapel project, Catherine chose Francesco Primaticcio, who had worked for Henry at Fontainebleau. Primaticcio designed the chapel as a round building, crowned by a dome, to be joined to the north transept of the basilica. The interior and exterior of the chapel were to be decorated with pilasters, columns, and epitaphs in coloured marble. The building would contain six other chapels circling the tomb of Henry and Catherine.[25] Primaticcio's circular design solved the problems faced by the Giusti brothers and Philibert de l'Orme, who had built previous royal tombs. Whereas de l'Orme had designed the tomb of Francis I to be viewed only from the front or the side, Primaticcio's design allowed the tomb to be viewed from all angles.[26] Art historian Henri Zerner has called the plan "a grand ritualistic drama which would have filled the rotunda's celestial space".[27]

Work on the chapel began in 1563 and continued over the next two decades. Primaticcio died in 1570, and the architect Jean Bullant took over the project two years later. After Bullant's death in 1578, Baptiste du Cerceau led the work.[28] Du Cerceau made minor alterations to Bullant's designs and completed the walls to the top of the second story when construction was abandoned in 1585. The chapel was demolished in the early 18th century.[29]

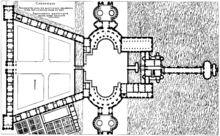

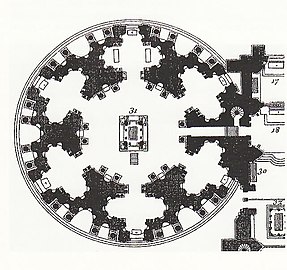

- Architectural designs for the Valois Chapel

-

Plan showing the chapel's location

-

Plan of the Valois Chapel

-

Elevation

Tomb

[edit]Several of the monuments built for the Valois chapel have survived. These include the tomb of Catherine and Henry, in Zerner's view, "the last and most brilliant of the royal tombs of the Renaissance".[30] Primaticcio himself designed its structure, which eliminated the traditional bas-reliefs and kept ornamentation to a minimum.[30] The sculptor Germain Pilon, who had provided statues for the tomb of Francis I, carved the tomb's two sets of effigies, which represented death below and eternal life above.[31] The King and Queen, cast in bronze, kneel in prayer (priants) on a marble canopy supported by twelve marble columns. Their poses echo those on the nearby tombs of Louis XII and Francis I. Pilon's feel for the material, however, invests his statues with a greater sense of movement.[32]

The remains of the King and Queen originally lay in the mortuary chamber below,[33] but in 1793, a mob tossed Catherine and Henry's bones into a pit with the rest of the French kings and queens.[34] Catherine's effigy suggests sleep rather than death, while Henry is posed strikingly, with his head thrown back.[35] From 1583, Pilon also sculpted two later gisants of Catherine and Henry wearing their crowns and coronation robes.[36] In this case, he portrays Catherine realistically, with a double chin. These two statues were intended to flank the altar of the chapel.[37] Pilon's four bronze statues of the cardinal virtues stand at the corners of the tomb. Pilon also carved the reliefs round the base that recall Bontemps' work on the monument for the heart of Francis I.[38]

- Tomb of Henri II and Catherine de' Medici

-

Drawing of how the tomb of Henry II and his wife originally looked; it shows the Effigies at top and the double tomb below

-

Tomb of Henry II and Catherine de' Medici, Basilica of Saint-Denis, with marble effigies on top

-

Close up of the Effigies on the tomb of Henry II and Catherine de' Medici at the Basilica of Saint-Denis, carved by Germain Pilon[39]

Statuary

[edit]

In the 1580s, Pilon began work on statues for the chapels that were to circle the tomb. Among these, the fragmentary Resurrection, now in the Louvre, was designed to face the tomb of Catherine and Henry from a side chapel.[40] This work owes a clear debt to Michelangelo, who had designed the tomb and funerary statues for Catherine's father at the Medici Chapels in Florence.[41] Pilon's statue of St Francis in Ecstasy now stands in the church of St Jean and St François. In art historian Anthony Blunt's view, it marks a departure from the tension of Mannerism and "almost foreshadows" the Baroque.[42]

Pilon had by this time developed a freer style of sculpture than previously seen in France. Earlier French sculpture seems to have influenced him less than Primaticcio's decorations at Fontainebleau:[38] the work of his predecessor Jean Goujon, for example, is more linear and classical.[43] Pilon openly depicts extreme emotion in his work, sometimes to the point of the grotesque. His style has been interpreted as a reflection of a society torn by the conflict of the French Wars of Religion.[44]

Montceaux

[edit]Catherine's earliest building project was the Château de Montceaux-en-Brie, near Paris, which Henry II gave her in 1556, three years before his death. The building consisted of a central pavilion housing a straight staircase, and two wings with a pavilion at each end. Catherine wanted to cover the alley in the garden where Henry played pall mall, an early form of croquet. For this commission, Philibert de l'Orme built her a grotto. He set it on a base made to look like natural rock, from which guests could watch the games while taking refreshments. The work was completed in 1558 but has not survived.[45] The château ceased to be used as a royal residence after 1640, and had fallen into ruin by the time it was demolished by revolutionary decree in 1798.[46]

Tuileries

[edit]

After the death of Henry II, Catherine abandoned the palace of the Tournelles, where Henry had lain after a lance fatally pierced his eye and brain in a joust.[47] To replace the Tournelles, she decided in 1563 to build herself a new Paris residence on the site of some old tile kilns or tuileries. The site was close to the congested Louvre, where she kept her household. The grounds extended along the banks of the Seine and afforded a view of the countryside to the south and west.[48] The Tuileries was the first palace that Catherine had planned from the ground up. It was to grow into the largest royal building project of the last quarter of the sixteenth century in western Europe. Her massive building schemes would have transformed western Paris, as seen from the river, into a monumental complex.[49]

To design the new palace, Catherine brought back Philibert de l'Orme from disgrace. This arrogant genius had been sacked as superintendent of royal buildings at the end of Henry II's reign, after making too many enemies.[50] De l'Orme mentioned the project in his treatises on architecture, but his ideas are not fully known. It appears from the small amount of work carried out that his plans for the Tuileries departed from his known principles. De l'Orme is said to have "taught France the classical style—lucid, rational and regular".[51] He notes, however, that in this case he added rich materials and ornaments to please the queen.[52] The plans therefore include a decorative element that looks forward to Jean Bullant's later work and to a less classical style of architecture.[53]

For the pilasters of Catherine's palace, de l'Orme chose the Ionic order, which he considered a feminine form:

I will not go on to other matters without pointing out to you that I chose the present Ionic order, from amongst all others, in order to ornament and to give lustre to the palace, which Her Majesty the Queen, mother of the most Christian King Charles IX, today is having built at Paris ... The other reason why I wanted to use and to show the Ionic order properly, on the palace of Her Majesty the Queen, is because it is feminine and was devised according to the proportions and beauties of women and goddesses, as was the Doric to those of men, which is what the ancients have told me: for, when they decided to build a temple to a god, they used the Doric, and to a goddess, the Ionic. Yet all architects have not followed that [principle], shown in Vitruvius's text ... accordingly I have made use, at the palace of Her Majesty the Queen, of the Ionic order, on the view that it is delicate and of greater beauty than the Doric, and more ornamented and enriched with distinctive features.[54]

Catherine de' Medici was closely involved in planning and supervising the building.[55] De l'Orme records, for example, that she told him to take down some Ionic columns that struck her as too plain. She also insisted on large panels between the dormers to make room for inscriptions.[56] Only a part of de l'Orme's scheme was ever built: the lower section of a central pavilion, containing an oval staircase, and a wing on either side.[53] Though work on de l'Orme's design was abandoned in 1572, two years after his death, it is nonetheless held in high regard. According to Thomson, "The surviving portions of the palace scattered between the Tuileries gardens, the courtyards of the École des Beaux-Arts [Paris] and the Château de la Punta in Corsica show that the columns, pilasters, dormers and tabernacles of the Tuileries were the outstanding masterpieces of non-figurative French Renaissance architectural sculpture".[57]

De l'Orme's original plans have not survived. Jacques Androuet du Cerceau, however, has left us a set of plans for the Tuileries. One engraving shows a grandiose palace, with three courts and two oval halls. This design is atypical of de l'Orme's style and so is likely to have been du Cerceau's own proposal or his son Baptiste's.[58] It recalls the houses with tall pavilions and multiple courtyards that du Cerceau often drew in the 1560s and 1570s. Architectural historian David Thomson suggests that the oval halls within du Cerceau's courtyards were Catherine de' Medici's idea. She may have planned to use them for her famously lavish balls and entertainments.[59] Du Cerceau's drawings reveal that, before he published them in 1576, Catherine decided to join the Louvre to the Tuileries by a gallery running west along the north bank of the Seine. Only the ground floor of the first section, the Petite Galerie, was completed in her lifetime.[60] It was left to Henry IV, who ruled from 1589 to 1610, to add the second floor and the Grande Galerie that finally linked the two palaces.[61]

After de l'Orme died in 1570, Catherine abandoned his design for a freestanding house with courtyards. To his unfinished wing she added a pavilion that extended the building towards the river. This was built in a less experimental style by Jean Bullant. Bullant attached columns to his pavilion, as advocated in his 1564 book on the classical orders, to mark proportion. Some commentators have interpreted his different approach as a criticism of de l'Orme's departures from the style of Roman monuments.[62]

Despite its unfinished state, Catherine often visited the palace. She held banquets and festivities there and loved to walk in the gardens.[48] In June 1572, Charles IX of France brought English diplomats to the gardens to "see the designs of his mother", and they dined in a slated-roofed open-sided pavilion or banqueting house.[63] According to the French military leader Marshal Tavannes, it was in the Tuileries Garden that she planned the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre, in which thousands of Huguenots were butchered in Paris.[64] The gardens had been laid out before work on the palace halted. They included canals, fountains, and a grotto decorated with glazed animals by the potter Bernard Palissy.[65] In 1573, Catherine hosted the famous entertainment at the Tuileries that is depicted on the Valois Tapestries. This was a grand ball for the Polish envoys who had come to offer the crown of Poland to her son, the duke of Anjou, later Henry III of France.[66] Henry IV later added to the Tuileries; but Louis XVI was to dismantle sections of the palace. The communards set fire to the remainder in 1871. Twelve years later, the ruins were demolished and then sold off.[67]

Saint-Maur

[edit]

architect: Philibert de l'Orme

The palace of Saint-Maur-des-Fossés, south east of Paris, was another of Catherine's unfinished projects. She bought this building, on which Philibert de l'Orme had worked, from the heirs of Cardinal Jean du Bellay, after the latter's death in 1560.[68] She then commissioned de l'Orme to finish the work he had begun there. Drawings by Jacques Androuet du Cerceau in the British Museum may shed light on Catherine's intentions for Saint-Maur. They show a plan to enlarge each wing by doubling the size of the pavilions next to the main block of the house. The house was to stay as one storey, with a flat roof and rusticated pilasters. That meant the extensions would not unbalance the masses of the building as seen from the side.[53]

De l'Orme died in 1570; in 1575 an unknown architect took over at Saint-Maur.[69] The new man proposed to heighten the pavilions on the garden side and top them with pitched roofs. He also planned two more arches over de l'Orme's terrace, which joined the pavilions on the garden side.[70] In historian Roberrt Knecht's view, the scheme would have given this part of the house, a "colossal, even grotesque" pediment.[71] The work was only partly carried out, and the house was never fit for Catherine to live in. The Château de Saint-Maur, still in the possession of the Condé family, was nationalised during the French Revolution, emptied of its contents, and its terrains divided up among real-estate speculators. The structure was demolished for the value of its materials; virtually nothing remains.

Hôtel de la Reine

[edit]

After de l'Orme's death, Jean Bullant replaced him as Catherine's chief architect. In 1572, Catherine commissioned Bullant to build a new home for her within the Paris city walls. She had outgrown her apartments at the Louvre and needed more room for her swelling household.[72] To make space for the new scheme and its gardens, she had an entire area of Paris demolished.[73]

The new palace was known in Catherine's time as the Hôtel de la Reine and later as the Hôtel de Soissons.[10] Engravings made by Israel Silvestre in about 1650 and a plan from about 1700 show that the Hôtel de la Reine possessed a central wing, a courtyard, and gardens.[74] The walled gardens of the hôtel included an aviary, a lake with a water jet, and long avenues of trees. Catherine also installed an orangery that could be dismantled in winter.[65] The actual construction work was carried out after Bullant's death in 1582.[75] The building was demolished in the 1760s. All that remains of the Hôtel de la Reine today is a single Doric column, known as the Colonne de l'Horoscope or Medici column, which stood in the courtyard.[76] It can be seen next to the domed Bourse de commerce. Catherine's biographer Leonie Frieda has called it "a poignant reminder of the fleeting nature of power".[77]

Chenonceau

[edit]

In 1576, Catherine decided to enlarge her château of Chenonceau, near Blois. On Henry II's death, she had demanded this property from Henry's mistress Diane de Poitiers. She had not forgotten that Henry had given this crown property to Diane instead of to her.[78] In return, she gave Diane the less prized Chaumont.[65] When Diane arrived at Chaumont, she found signs of the occult, such as pentangles drawn on the floor. She quickly withdrew to her château of Anet and never set foot in Chaumont again.[79]

Diane had carried out major works at Chenonceau, such as de l'Orme's bridge over the Cher. Now Catherine set out to efface or outdo her former rival's work.[78] She lavished vast sums on the house and built two galleries on the extension over the bridge. The architect was almost certainly Bullant. The decorations show the fantasy of his late style.[80]

Catherine loved gardens and often conducted business in them.[81] At Chenonceau, she added waterfalls, menageries, and aviaries, laid out three parks, and planted mulberry trees for silkworms.[65] Jacques Androuet du Cerceau made drawings of a grandiose scheme for Chenonceau. A trapezoidal lower court leads to a forecourt of semicircular atria joined to two halls that flank the original house.[82] These drawings may not be a reliable record of Bullant's plans. Du Cerceau "sometimes inserted in his book designs embodying ideas which he himself would have liked to see carried out rather than those of the actual designer of the building in question".[83]

Jacques Androuet du Cerceau was a favourite architect of Catherine's. Like Bullant, he became a more fantastical designer with time.[84] Nothing he built himself, however, has survived. He is known instead for his engravings of the leading architectural schemes of the day, including Saint-Maur, the Tuileries, and Chenonceau.[82] In 1576 and 1579, he produced the two-volume Les Plus Excellents Bastiments de France, a beautiful publication dedicated to Catherine.[85] His work is an invaluable record of buildings that were never finished or were later substantially altered.[86]

End of the dynasty

[edit]Catherine spent ruinous sums of money on buildings at a time of plague, famine, and economic hardship in France.[87] As the country slipped deeper into anarchy, her plans grew ever more ambitious.[88] Yet the Valois monarchy was crippled by debt and its moral authority was in steep decline. The popular view condemned Catherine's building schemes as obscenely extravagant. This was especially true in Paris, where the parlement was often asked to contribute to her costs.

Pierre de Ronsard captured the mood in a poem:

The queen must cease building,

Her lime must stop swallowing our wealth...

Painters, masons, engravers, stone-carvers

Drain the treasury with their deceits.

Of what use is her Tuileries to us?

Of none, Moreau; it is but vanity.

It will be deserted within a hundred years.[89]

Ronsard was in many ways proved correct. The death of Catherine's beloved son Henry III in 1589, a few months after her own, brought the Valois dynasty to an end. Precious little of Catherine's grand building work has survived.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d Knecht, 220.

- ^ Frieda, 79.

- ^ "The Day of the Barricades" (12 May 1588), in which a mob took over the streets of Paris, "reduced the authority and prestige of the monarchy to its lowest ebb for a century and a half". Morris, 260.

- ^ The architect Philibert de l'Orme wrote: "your good judgement (bon esprit) shows itself more and more and shines as you yourself take the trouble to project and sketch out (protraire et esquicher) the buildings which it pleases you to commission". Knecht, 228.

- ^ Knecht, 228. The poet Ronsard accused her of preferring masons to poets.

- ^ Babelon, The Louvre, 263.

- ^ Frieda, 24.

- ^ Frieda, 30–31.

- ^ Hautecœur, 523.

- ^ a b Thomson, 176.

- ^ Knecht 176; Frieda, 199.

- ^ Frieda, 79, 455; Sutherland, 6.

- ^ Blunt, Art and Architecture in France, 80. These extensions, supervised by Pierre Lescot and featuring relief sculptures by Jean Goujon, were continued by the last four Valois kings.

- ^ Norwich, 158.

- ^ Thornton, 51.

- ^ Norwich, 157.

- ^ Hoogvliet, 111. Some scholars believe that the intertwined letter Cs may also refer to crescent moons, the emblem of Henry's lover Diane de Poitiers (the crescent moon was the symbol of the goddess Diana). However, Catherine continued to use this monogram after Henry's death.

- ^ Knecht, 58.

- ^ "Catherine's lifelong mourning was not only a manner to express grief: it was also the legitimisation of her political role." Hoogvliet, 106.

- ^ a b Knecht, 223.

- ^ Frieda, 266; Hoogvliet, 108. Louis Le Roy, in his Ad illustrissimam reginam D. Catherinam Medicem of 1560, was the first to call Catherine the "new Artemisia".

- ^ Quoted by Knecht, 224. Catherine commissioned the artists Niccolò dell'Abbate and Antoine Caron to illustrate the poem. The drawings were subsequently turned into tapestries, none of which survive; but, according to Knecht, fifty-nine of the drawings survive. Hoogvliet, 108, on the other hand, says that sixty-eight of the drawings survive.

• Frieda, 266. The story of Artemisia formed an iconography for Catherine and reinforced her right to serve as regent. The later female regents Marie de' Medici (1610–20) and Anne of Austria (1643–60) revived this iconography in their own service. - ^ Zerner, 383.

- ^ Zerner, 382.

- ^ Hoogvliet, 109.

- ^ Blunt, Art and Architecture in France, 56.

- ^ L'art de la Renaissance en France. L'invention du classicisme (Zerner, 1996: 349–54), quoted by Knecht, 227.

- ^ Knecht, 226.

- ^ Blunt, Art and Architecture in France, 56–59

- ^ a b Zerner, 379.

- ^ "With the rise of naturalistic representations beginning in the fifteenth century, the afterlife was imagined as an exact replica of earthly existence. As a result, the tombs of the mighty often insinuated an ambiguous conflation of the glorious Life Eternal with a glorification of their earthly lives." Zerner, 380.

- ^ Blunt, Art and Architecture in France, 94. Blunt believes that Benvenuto Cellini's Fontainebleau nymph may have influenced their carving.

- ^ Zerner 383–84. Girolamo della Robbia was originally commissioned to carve the queen's corpse, but his effort, in which Catherine looks emaciated, was left unfinished in 1566 and is now in the Louvre.

- ^ Knecht, 269.

- ^ Zerner, 379; Blunt, Art and Architecture in France, 95.

- ^ Zerner suggests that these two, apparently superfluous, recumbent effigies, as rigid as those from the thirteenth century, might have been a "call to order". In the context of the wars of religion, they may have represented a pulling back from the sensuality of the tomb, which "was bound to appear somewhat pagan". Zerner, 382–83.

- ^ Knecht, 226–27.

- ^ a b Blunt, Art and Architecture in France, 94.

- ^ Knecht, 227. Henry's gesture is now unclear, since a missal, resting on a prie-dieu (prayer desk), was removed from the sculpture during the French revolution and melted down.

- ^ Zerner, 383. Whereas the "Resurrection" for the tomb of Francis I was positioned close to the corpses, this design would have involved the visitor.

- ^ Blunt, Art and Architecture in France, 95. Pilon based the Christ on Michelangelo's cartoon for Noli me tangere (1531) and carved the soldiers in Michelangelo's contrapposto style.

- ^ Blunt, Art and Architecture in France, 95.

- ^ Blunt, Art and Architecture in France, 94, 97.

- ^ Blunt, Art and Architecture in France, 96–97.

- ^ Knecht, 228–229.

- ^ Coope, "The Chateau of Montceaux-en-Brie", 71–87.

- ^ Blunt, Art and Architecture in France, 104. Catherine planned a grid of streets to replace the palace, with houses designed by de l'Orme, but the work was never carried out. Henry IV, who ruled France from 1589 to 1610, later constructed a square on the site called the Place Royale, now known as the Place des Vosges.

- ^ a b Frieda, 335.

- ^ Thomson, 165.

• This engraving by Matthäus Merian shows the complex in 1615, after Henry IV's additions. - ^ Knecht, 229. Historian R. J. Knecht suggests, (after Blunt, Philibert de l'Orme, London, 1958), that Catherine may have been moved to rehabilitate de l'Orme after reading his Instruction, in which he defended himself against all charges and pleaded for fair treatment.

• Randall, 82–84. The reasons for de l'Orme's disgrace are not clear, but it seems that he was prone to arrogance and had made enemies.

• Zerner, 402. Zerner, who calls him "haughty", mentions allegations of embezzlement and an incident in which de l'Orme and his brother killed two men in a brawl. - ^ Sharp, 44.

- ^ De l'Orme recorded that Catherine told him "to make several encrustations of different kinds of marble, gilded bronze and of minerals, like marcassites" on both the inside and the outside of the building. Knecht, 228.

- ^ a b c Blunt, Art and Architecture in France, 55.

- ^ Quoted by Thomson, 169.

- ^ De l'Orme wrote that Catherine, with "an admirable understanding combined with great prudence and wisdom," took the trouble "to order the organization of her said palace (the Tuileries) as to the apartments and location of the halls, antechambers, chambers, closets and galleries, and to give the measurements of width and length". Quoted by Knecht, 228.

- ^ Thomson, 171; Blunt, Art and Architecture in France, 55. The way the dormers overlap the pedimented panels gives the effect of blurrier lines than in the more classical works de l'Orme had designed for Henry II.

- ^ Thomson, 171

• Pons, 79. Counts Jérome and Charles Pozzo di Borgo bought sections of the ruins during the demolition of the Tuileries in 1883 and used them to construct the Château de la Punta in Corsica, overlooking the gulf of Ajaccio (1885–7). - ^ Knecht, 229; Thomson 165–66.

- ^ Thomson, 168. In June 1565 and September 1581, Catherine had temporary oval structures built to house entertainments for state occasions.

- ^ Thomson, 173. The reliefs on the arches of the Petite Galerie, like those on the court front of the Louvre, symbolise the might and moral authority of the Valois monarchy. Those of de l'Orme at the Tuileries are purely classical in style and follow the principles of Vitruvius.

- ^ Thomson, 172.

- ^ Thomson, 173–4. The only elements Bullant harmonised with de l'Orme's work were the ground-floor Ionic columns and the frieze and cornice between the first and ground floors.

- ^ Henry Ellis, Original Letters, series 2 vol. 3 (London, 1827), p. 18

- ^ Frieda, 306.

- ^ a b c d Knecht, 232.

- ^ Knecht, 230.

- ^ Ayers, 42.

- ^ Blunt, Art and Architecture in France, 49.

- ^ Blunt, Art and Architecture in France, 89, believes this architect was Jean Bullant, of whom he writes: "In these last years, Bullant's desire for the colossal seems to have grown greater, and in this case it could not be harmonized with the existing building".

- ^ Knecht, 231. The terrace was supported by a cryptoporticus, a covered passageway.

- ^ Knecht, 231.

- ^ Knecht, 230. Between 1575 and 1583, for example, the number of Catherine's ladies-in-waiting rose from 68 to 111.

- ^ Frieda, 335. The area, in the parish of Saint-Eustache, included the Hôtel Guillart and the Hôtel d'Albret.

- ^ Plan of the Hôtel de la Reine, from an engraving of about 1700. Thomson, 176.

- ^ Thomson, 176–7.

- ^ Thomson, 176

- ^ Frieda, 455.

- ^ a b Frieda, 144.

- ^ Frieda, 148.

- ^ Blunt, Art and Architecture in France, 89.

- ^ Benes, 211.

- ^ a b Thomson, 165.

- ^ Knecht, 232, quotes Blunt, Philibert de l'Orme (London, 1958), 89–91.

- ^ Blunt, Art and Architecture in France, 90.

- ^ Blunt, Art and Architecture in France, 91. The original drawings are now in the British Museum.

- ^ Blunt, Art and Architecture in France, 91.

- ^ Cunningham, 280–81. So widespread and serious was the plague of 1565, for example, that Catherine had the surgeon Ambroise Paré write an account of it. He concluded that plague resulted from poisoning of the air and was "often sent by the just anger of God punishing our offences".

- ^ Thomson, 168.

- ^ Knecht, 233. Ronsard addressed these lines to the financial official Raoul Moreau. Au tresorier de l'esparne (ca. 1573).

References

[edit]- Ayers, Andrew. The Architecture of Paris. Stuttgart: Edition Axel Menges, 2004. ISBN 3-930698-96-X.

- (in French) Babelon, Jean-Pierre. Châteaux de France au siècle de la Renaissance. Paris: Flammarion/Picard, 1989. ISBN 2-08-012062-X.

- Babelon, Jean-Pierre. "The Louvre: Royal Residence and Temple of the Arts". Realms of Memory: The Construction of the French Past. Vol. III: Symbols. Edited by Pierre Nora. English language edition edited by Lawrence D. Kritzman and translated by Arthur Goldhammer. New York: Columbia University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-231-10926-1.

- Benes, Mirka. Villas and Gardens in Early Modern Italy and France. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-521-78225-2.

- Blunt, Anthony. Art and Architecture in France: 1500–1700. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, [1957] 1999 edition. ISBN 0-300-07748-3.

- Blunt, Anthony. Philibert de l'Orme. London: Zwemmer, 1958. OCLC 554569.

- (in French) Bullant, Jean. Reigle generalle d'architectvre des cinq manieres de colonnes, á sçauoir, Tuscane, Dorique, Ionique, Corinthe, & Coposite; enrichi de plusieurs autres, à l'exemple de l'antique; veu, recorrigé & augmenté par l'auteur de cinq autre ordres de colonnes auiuant les reigles & doctrine de Vitruue; au proffit de tous ouvriers besongnans au compas & à l'esquierre a Escouën par Iehan Bullant. Paris: Hierosme de Marnef & Guillaume Cauellat, 1568. OCLC 20861874.

- (in French) Du Cerceau, Jacques Androuet. Les plus excellents bastiments de France. Paris: Sand & Conti, [1576, 1579] 1988 edition. ISBN 2-7107-0420-X.

- Chastel, A. French Art: The Renaissance, 1430–1620. Translated by Deke Dusinberre. Paris: Flammarion, 1995. ISBN 2-08-013583-X.

- Coope, Rosalys. "The Chateau of Montceaux-en-Brie." Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. 22, No. 1/2 (Jan.–Jun., 1959), 71–87. Retrieved 29 March 2008.

- Cunningham, Andrew, and Ole Peter Grell. The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse: Religion, War, Famine and Death in Reformation Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-521-46701-2.

- Frieda, Leonie. Catherine de Medici. London: Phoenix, 2005. ISBN 0-7538-2039-0.

- (in French) Hautecœur, Louis. Histoire de l'architecture classique en France. Paris: Picard, 1943. OCLC 1199768.

- Hoogvliet, Margriet. "Princely Culture and Catherine de Médicis". Princes and Princely Culture, 1450–1650. Edited by Martin Gosman, Alasdair A. MacDonald, and Arie Johan Vanderjagt. Leiden and Boston, MA: Brill Academic, 2003. ISBN 90-04-13572-3.

- Knecht, R. J. Catherine de' Medici. London and New York: Longman, 1998. ISBN 0-582-08241-2.

- Morris, T. A. Europe and England in the Sixteenth Century. London and New York: Routledge, 1998. ISBN 0-415-15040-X.

- Neale, J. E. The Age of Catherine de' Medici. London: Jonathan Cape, 1945. OCLC 39949296.

- Norwich, John Julius. Great Architecture of the World. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo, 2001 edition. ISBN 0-306-81042-5.

- (in French) L'Orme, Philibert de. Architecture de Philibert de L'Orme. Oeuvre entiere contenant unze livres, augmentée de deux; & autres figures non encores veuës, tant pour desseins qu'ornemens de maison. Avec une belle invention pour bien bastir, & à petits frais. Ridgewood, NJ: Gregg Press, [Reprint of the 1648 Rouen edition] 1964. OCLC 1156874.

- Pons, Bruno. Architecture and Panelling: The James. A. Rothschild Bequest at Waddesdon Manor. London: Philip Wilson, 2001. ISBN 0-85667-437-0.

- Randall, Catharine. Building Codes: The Aesthetics of Calvinism in Early Modern Europe. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8122-3490-1.

- Sharp, Dennis, ed. The Illustrated Dictionary of Architecture and Architects. London: Headline, 1991. ISBN 0-7472-0271-0.

- Sutherland, N. M. Catherine de Medici and the Ancien Régime. London: Historical Association, 1966. OCLC 1018933.

- Thomson, David. Renaissance Paris: Architecture and Growth, 1475-1600. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984. ISBN 0-520-05347-8. Retrieved 21 March 2008.

- Thornton, Peter. Form and Decoration: Innovation in the Decorative Arts, 1470–1870. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2000. ISBN 0-297-82488-0.

- Zerner, Henri. Renaissance Art in France. The Invention of Classicism. Translated by Deke Dusinberre, Scott Wilson, and Rachel Zerner. Paris: Flammarion, 2003. ISBN 2-08-011144-2.

External links

[edit]- (in French) Architectura: Les Livres d'Architecture. Architecture, Textes et Images, XVI–XVII siècles. Academic website containing texts, drawings, and bibliographical material about sixteenth- and seventeenth-century French architects, including Philibert de l'Orme, Jacques Androuet du Cerceau, and Jean Bullant. A large-scale project in development.

![Close up of the Effigies on the tomb of Henry II and Catherine de' Medici at the Basilica of Saint-Denis, carved by Germain Pilon[39]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5e/Basilica_di_saint_Denis_tomba_enrico_II_e_caterina_de%27_Medici_03.JPG/400px-Basilica_di_saint_Denis_tomba_enrico_II_e_caterina_de%27_Medici_03.JPG)