Car-free movement

The car-free movement is a social movement centering the belief that large and/or high-speed motorized vehicles (cars, trucks, tractor units, motorcycles, etc.)[1] are too dominant in modern life, particularly in urban areas such as cities and suburbs. It is a broad, informal, emergent network of individuals and organizations, including social activists, urban planners, transportation engineers, environmentalists and others. The goal of the movement is to establish places where motorized vehicle use is greatly reduced or eliminated, by converting road and parking space to other public uses and rebuilding compact urban environments where most destinations are within easy reach by other means, including walking, cycling, public transport, personal transporters, and mobility as a service.[2]

Context

[edit]

Before the twentieth century, cities and towns were usually compact, containing narrow streets busy with human activity. In the early twentieth century, many of these settlements were adapted to accommodate the car with wider roads, more car parking spaces, and lower population densities, with space between urban buildings reserved for automotive use.[2] Lower population densities caused urban sprawl with longer distances between locations. This also brought traffic congestion which made older transport methods unattractive or impractical, and created the conditions for more traffic and sprawl; the car system was "increasingly able to 'drive' out competitors, such as feet, bikes, buses and trains".[3] This process led to changes in urban form and living patterns that offered little opportunity for people without a car.[4]

Some governments have responded with policies and regulations aimed at reversing auto dependency by increasing urban densities, encouraging mixed use development and infill, reducing space allocated to private cars, increasing walkability, supporting cycling and other alternative vehicles similar in size and speed, and public transport.[5] Globally, urban planning is evolving in an effort to increase public transport and non-motorized transport modal shares and shift away from private transport oriented development. Cities like Hong Kong developed a highly integrated public transportation system which effectively reduced the use of private transport.[6] In contrast with private automotive travel, car sharing, where people can easily rent a car for a few hours rather than own one, is emerging as an increasingly important element for urban transportation.[7]

Urban design

[edit]

Proponents of the car-free movement focus on both sustainable and public transport (bus, tram, etc.) options and on urban design, zoning, school placement policies, urban agriculture, remote work options, and housing developments that create proximity or access so that long-distance transportation becomes less of a requirement of daily life.

New urbanism is an American urban design movement that arose in the early 1980s. Its goal has been to reform all aspects of real estate development and urban planning, from urban retrofits to suburban infill. New urbanist neighborhoods are designed to contain a diverse range of housing and jobs, and to be walkable.[8] Other, more auto-oriented cities are also making incremental changes to provide transportation alternatives through Complete streets improvements.

World Squares for all is a scheme to remove much of the traffic from major squares in London, including Trafalgar Square and Parliament Square.[9]

Car-free cities are, as the name implies, entire cities (or at least the inner parts thereof) which have been made entirely car-free.

Car-free zones are areas of a city or town where the use of cars is prohibited or greatly restricted.[10]

To make the car-free zones/cities, (movable and/or stationary) traffic bollards and other barriers are often used to deny car access.

Living streets and complete streets prioritize the needs of users of the street as a whole over those of car drivers. They are designed to be shared by pedestrians, playing children, bicyclists, and low-speed motor vehicles.[11]

Distribution centers allow easy restocking of supermarkets, outlet stores, restaurants, and more in city centers. They rely on tractor units to unload their cargo in the suburban distribution center. The products are then placed in a small truck (sometimes electrically powered[12]), cargo bike, or other vehicle to bridge the last mile to the destination in the city center. Besides offering advantages to the population (increased safety due to truck drivers having less blind spots, reduced noise pollution and traffic, reduced tailpipe emissions and reduced air pollution, and more), it also offers financial advantage for the companies, as tractor units require a lot of time to bridge this last mile (they lack agility and consume much fuel in congested streets).

The method above however still does not reduce car use inside non-car-free city centers (customers often use cars to fetch their groceries or appliances from city stores, since they have so much storage space). This problem is solved by means of online food ordering systems, which allow customers to order online, and then have it delivered to their doorstep by the supermarket or store itself, through bicycle couriers (using cargo bikes), electric delivery robots and delivery vans.[13][14] Delivery vans allow to take along more cargo and deliver to several customers on a same trip. These food ordering systems could provide for a smooth transition for those cities that wish to become car-free as it can reduce both personal car use and personal car demand in cities.

At the outskirts of towns, between the exits of the rings roads, and the car-free zones in the city center themselves, additional car parking lots can be added, generally in the form of underground car parks (to avoid it taking up surface space).[15] Careful placement of these car-parking lots is needed though, ensuring that they are made far enough from the city centers (and closer to the ring roads) to avoid them attracting more cars to the city center. In some instances, near these car parking lots, Park and ride public transport (i.e. bus) stops are foreseen, or bicycle-sharing systems are present.[citation needed]

Community bicycle programs provide bicycles within an urban environment for short term use. The first successful scheme was in the 1960s in Amsterdam and can now be found in many other cities with 20,000 bicycles introduced to Paris in 2007 in the Vélib' scheme.[16] Dockless bike share systems have recently appeared in the United States and provide more convenience for people wanting to rent a bike for a short time period.[17]

Advocacy groups

[edit]The Campaign for Better Transport (formerly known as Transport2000) was formed in 1972 in Britain to challenge proposed cuts in the British rail network and since then has promoted public transport.[18]

Car Free Walks is a UK-based website encouraging walkers to use public transport to reach the start and end of walks, rather than using a car.[19]

Activism groups

[edit]Road protests in the United Kingdom rose to prominence in the early 1990s in response to a major road building program both in urban communities and also rural areas.[20]

Reclaim the Streets, a movement formed in 1991 in London, "invaded" major roads, highway or freeway to stage parties. While this may obstruct the regular users of these spaces such as car drivers and public bus riders, the philosophy of RTS is that it is vehicle traffic, not pedestrians, who are causing the obstruction, and that by occupying the road they are in fact opening up public space.[21]

In Flanders, the organization Fietsersbond has called upon the government to ban tractor units in city centers.[22][23]

Critical Mass rides emerged in 1992 in San Francisco where cyclists take to the streets en masse to dominate the traffic, using the slogan "we are traffic." The ride was founded with the idea of drawing attention to how unfriendly the city was to bicyclists.[24] The movement has grown to include events in major metropolitan cities around the world.

The World Naked Bike Ride was born in 2001 in Spain with the first naked bike rides, which then emerged as the WNBR in 2004 a concept which rapidly spread through collaborations with many different activist groups and individuals around the world to promote bicycle transportation, renewable energy, recreation, walkable communities, and environmentally responsible, sustainable living.[25]

Parking Days started in 2005 when REBAR, a collaborative group of creators, designers and activists based in San Francisco, transformed a metered parking spot into a small park complete with turf, seating, and shade[26] and by 2007 there were 180 parks in 27 cities around the world.[27]

r/fuckcars is an anti-car subreddit with 440,000 members as of July 2024.[28]

Official events

[edit]Car Free Days are official events with the common goal of taking a fair number of cars off the streets of a city or some target area or neighborhood for all or part of a day, in order to give the people who live and work there a chance to consider how their city might look and work with significantly fewer cars. The first events were organized in Reykjavík (Iceland), Bath (UK) and La Rochelle (France) in 1995.[29] Jakarta, Indonesia is one such city that hosts weekly Car-Free days.[30]

Ciclovía is a similar event in many cities that places a large emphasis on cycling as an alternative to auto travel. The event originated in Bogotá, Colombia in 1974. Now, Bogotá holds weekly ciclovías that turn the streets into giant car-free celebrations complete with stages set up in city parks with aerobics instructors, yoga teachers, and musicians leading people through various performances. The event has inspired similar celebrations globally.[31]

In town, without my car! is an EU campaign and day every autumn (Northern Hemisphere) for an increased use of vehicles other than the car. It has since spread beyond the EU, and in 2004 more than 40 countries participated.[32]

World Urbanism Day was founded in 1949 in Buenos Aires and is celebrated in more than 30 countries on four continents each November 8.[33]

Towards Car-free Cities is the annual conference of the World Car-free Network and provides a focal point for diverse aspects of the emerging global car-free movement. The conference has been held in major cities around the world, including Portland, Oregon, United States in 2008 (its first time in North America), and has also been in Istanbul, Turkey; Bogota, Colombia; Budapest, Hungary; Berlin, Germany; Prague, Czech Republic; Timișoara, Romania; and Lyon, France. The conference series attempts to bridge the gap between many of the diverse people and organizations interested in reducing urban dependence on the automobile.

Transportation Alternatives' Annual Commuter Race pits a bicyclist against both a subway rider and a cab rider in a race from Queens to Manhattan. The Fifth Annual Commuter race took place in May 2009, where bicyclist Rachel Myers beat straphanger Dan Hendrick and cab rider Willie Thompson to make it the fifth year the contestant on the bicycle won. Myers took the 2009 title with a time of 20 minutes and 15 seconds to make the 4.2 mile trek from Sunnyside, Queens to Columbus Circle in Manhattan. Hendrick showed up 15 minutes later off the subway and Thompson arrived via cab nearly a half-hour after that. Transportation Alternatives is a group that "seeks to change New York City's transportation priorities to encourage and increase non-polluting, quiet, city-friendly travel and decrease—not ban—private car use. [They] seek a rational transportation system based on a 'Green Transportation Hierarchy,' which gives preference to modes of travel based on their benefits and costs to society. To achieve its goals, T.A. works in five areas: Bicycling, Walking and Traffic Calming, Car-Free Parks, Safe Streets and Sensible Transportation." The 2009 Commuter Race came on the heels of a Times Square traffic ban in NYC that drew national media attention.[34]

Car-free development

[edit]Definitions and types

[edit]There are many areas of the world where people have always lived without cars, because no road access is possible, or none has been provided. In developed countries these include islands and some historic neighborhoods or settlements, the largest example being the canal city of Venice. The term carfree development implies a physical change – either new building or changes to an existing built area.

Melia et al. (2010)[35] define car-free development as follows:

Car-free developments are residential or mixed use developments which:

- Normally provide a traffic-free immediate environment, and:

- Offer no parking or limited parking separated from the residence, and:

- Are designed to enable residents to live without owning a car.

This definition (which they distinguish from the more common "low car development") is based mainly on experience in Northwestern Europe, where the movement for car-free development began. Within this definition three types are identified:

- Vauban model

- Limited Access model

- Pedestrian zones with residential population

Vauban

[edit]Vauban, Freiburg, Germany is according to this definition, the largest car-free development in Europe, with over 5,000 residents. Whether it can be considered car-free is open to debate: many local people prefer the term "stellplatzfrei" – literally "free from parking spaces" to describe the traffic management system there. Vehicles are allowed down the residential streets at walking pace to pick up and deliver but not to park, although there are frequent infractions. Residents of the stellplatzfrei areas must sign an annual declaration stating whether they own a car or not. Car owners must purchase a place in one of the multi-storey car parks on the periphery, run by a council-owned company. The cost of these spaces – €17,500 in 2006, plus a monthly fee – acts as a disincentive to car ownership.[35]

Limited access type

[edit]The more common form of car free development involves some sort of physical barrier, which prevents motor vehicles from penetrating into a car-free center. Melia et al.[35] describe this as the "Limited Access" type. In some cases such as Stellwerk 60 in Cologne, there is a removable barrier, controlled by a residents' organizations. In others cases, such as in Waterwijk, vehicular access is only available from the exterior.

Pedestrian zones

[edit]Whereas the first two models apply to newly built car free developments, most pedestrianized areas have been retro-fitted. Pedestrian zones may be considered car-free developments where they include a significant population and a low rate of vehicle ownership per household. The largest example in Europe is Groningen, Netherlands which had a city centre population of 16,500 in 2008.[36]

Benefits and problems

[edit]

Several studies have been done on European car free developments. The most comprehensive was conducted in 2000 by Jan Scheurer.[37] Other more recent studies have been made of specific car-free areas such as Vienna's Floridsdorf car-free development.[38]

The main benefits found for car free developments (summarized in Melia et al. 2010[35]) found in the various studies are:

- very low levels of car use, resulting in much less traffic on surrounding roads

- high rates of walking and cycling

- more independent movement and active play amongst children

- less land taken for parking and roads – more available for green or social space

The main problems are related to parking management - if parking is not controlled in the surrounding area, there are often complaints from neighbors about overspill parking.

Places

[edit]See also

[edit]- Alternatives to car use

- Automobile dependency

- Car costs

- Carfree city

- Car-Free Days

- Circulation plan

- Effects of the car on societies

- Free public transport

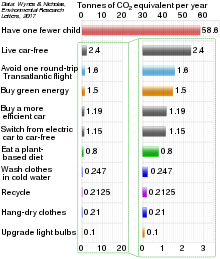

- Individual action on climate change

- Jane Jacobs

- Jan Gehl

- Donald Shoup

- List of car-free places

- Obesity and walking

- Peak car

- Principles of intelligent urbanism

- Road reallocation

- Street reclamation

- Transit-oriented development

- Urban planning

- Urban vitality

References

[edit]- ^ Car free movement opposing not only cars but many motorized vehicles

- ^ a b Zehner, Ozzie (2012). Green Illusions. London: University of Nebraska Press.

- ^ John Urry. "The 'System' of Automobility" (PDF). University of Lancacaster. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-12.

- ^ "Transport and Social Exclusion – a survey of the G7 nations: FIA Foundation and RAC Foundation" (PDF). RAC Foundation. 2004-02-01. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 18, 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-12.

- ^ "Sustainable travel". UK Department for Transport. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- ^ Step out of your cars to embrace your cities | Cities Now Archived September 23, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Car Clubs / Car Sharing Research Project – Motorists' Forum Conclusions and Recommendations". UK Commission for integrated transport. Archived from the original on 2008-01-26. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- ^ "New Urbanism". New Urbanism.org. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- ^ "World Squares for All". The Mayor of London. Archived from the original on 2007-08-08. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- ^ Charles Bremner (2005-03-15). "Paris bans cars to make way for central pedestrian zone". The Times. London. Archived from the original on October 13, 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- ^ "Concept Development: 'Woonerf'" (PDF). The International Institute for the Urban Environment. 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-10-11. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- ^ City depot employing a few electric trucks Archived September 12, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ DoorDash and Walmart join forces

- ^ Sainsbury's trials UK's first cargo bike

- ^ Plan to make Brussels car-free includes new underground parking spaces

- ^ Bennhold, Katrin (2007-07-16). "A New French Revolution's Creed: Let Them Ride Bikes". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- ^ "On Why Dockless Bike Share Systems are the Future – Car Free America". Car Free America. 2017-09-18. Retrieved 2017-10-29.

- ^ "The Campaign to save the Railway Network". Single or Return – the official history of the Transport Salaried Staffs' Association. The Transport Salaried Staffs’ Association (TSSA). Archived from the original on 2004-01-09. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- ^ "Car Free Walks". Retrieved 2008-02-29.

- ^ "1993: Activists lose battle over chestnut tree". BBC. 1993-12-07. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- ^ "The group reclaiming the headlines". BBC News. 1999-12-01. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- ^ Fietsersbond vraagt overheid tot verbieden van grote trucks

- ^ "Fietsersbond" or "cyclist union" in Flanders

- ^ Garofoli, Joe (2002-09-28). "Critical Mass turns 10". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2007-07-02.

- ^ "A history of unabashed free wheelers!". worldnakedbikeride.org. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- ^ "Parking day – background". parkingday.org. Archived from the original on 2007-08-08. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- ^ "Park(ing) Day 2007". Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- ^ Khan, Imad (2022-07-20). "High Gas Prices Are Revving Up This Online Anti-Car Movement". CNET. Retrieved 2022-10-13.

- ^ "World Car Free Days Timeline: 1961–2007". ecoplan. Archived from the original on 2008-01-13. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- ^ "Info Car Free Day - Official Media for Car Free Day". Info Car Free Day. Retrieved 2020-09-16.

- ^ "This city bans cars every Sunday—and people love it". Environment. 2019-03-27. Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved 2020-02-18.

- ^ "What is In Town, Without My Car?". UK Department for Transport. Archived from the original on 2008-01-20. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- ^ "THE MARSEILLES DECLARATION – WORLD TOWN PLANNING DAY (WTPD) 2005" (PDF). urbanists.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-08-21. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- ^ Neuman, William; Barbaro, Michael (February 2009). "Mayor Plans to Close Parts of Broadway to Traffic". The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-09-15.

- ^ a b c d Melia, S., Barton, H. and Parkhurst, G. (2010) Carfree, Low Car – What's the Difference? World Transport Policy & Practice 16 (2), 24-32. Archived 2016-01-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Statistical Yearbook 2008" (PDF). City of Groningen. Archived from the original on 2009-06-29. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- ^ Scheurer, J. (2001) Urban Ecology, Innovations in Housing Policy and the Future of Cities: Towards Sustainability in Neighbourhood CommunitiesThesis (PhD), Murdoch University Institute of Sustainable Transport.

- ^ Ornetzeder, M., Hertwich, E.G., Hubacek, K., Korytarova, K. and Haas, W. (2008) The environmental effect of car-free housing: A case in Vienna. Ecological Economics 65 (3), 516-530.

Further reading

[edit]- Katie Alvord, Divorce Your Car! Ending the Love Affair with the Automobile, New Society Publishers (2000), ISBN 0-86571-408-8

- Crawford, J. H., Carfree Cities, International Books (2000), ISBN 978-90-5727-037-6

- Crawford, J. H., Carfree Design Manual, (2009), ISBN 978-90-5727-060-4

- Zack Furness One Less Car: Bicycling and the Politics of Automobility, Temple University Press (2010), ISBN 978-1-59213-613-1

- Elisabeth Rosenthal, "In German Suburb, Life Goes on Without Car," New York Times, May 11, 2009.

- Lynn Sloman, Car Sick: Solutions for Our Car-addicted Culture, Green Books (2006), ISBN 978-1-903998-76-2

- Alex Steffen, Carbon Zero: Imagining Cities That Can Save the Planet

- Martin Wagner, The Little Driver, Pinter & Martin (2003), ISBN 978-0-9530964-5-9