Capture of Wakefield

| Capture of Wakefield | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the First English Civil War | |||||||

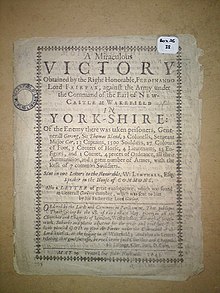

A Miraculous Victory obtained by the Right Honorable Ferdinando Lord Fairfax at Wakefield; pamphlet published in London on 27 May 1643 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Royalists | Parliamentarians | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| George Goring (POW) | Sir Thomas Fairfax | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| c. 3,000 | c. 1,500 | ||||||

Wakefield within West Yorkshire | |||||||

The capture of Wakefield occurred during the First English Civil War when a Parliamentarian force attacked the Royalist garrison of Wakefield, Yorkshire. The Parliamentarians were outnumbered, having around 1,500 men under the command of Sir Thomas Fairfax, compared to the 3,000 led by George Goring in Wakefield. Despite being outnumbered, Parliamentarians successfully stormed the town, taking roughly 1,400 prisoners.

Around 800 Parliamentarians had been taken prisoner after being defeated at Seacroft Moor, and Fairfax plotted the capture of Wakefield to take prisoners of his own to exchange for his men. He marched his force from Leeds and split it in two to attack from different directions. After around two hours of fighting early in the morning of 21 May, 1643, Fairfax broke through into Wakefield. Goring, who had been in bed suffering from either illness or a hangover, rose and led a counterattack in his nightshirt, but to no avail and the town was captured. Fairfax gained the prisoners he needed and much ammunition. According to his own account, the Parliamentarians lost no more than seven men.

Background

[edit]In March 1643, the First English Civil War had been running for seven months, since King Charles I had raised his royal standard in Nottingham and declared the Earl of Essex, and by extension Parliament, to be traitors.[1] That action had been the culmination of religious, fiscal and legislative tensions going back over fifty years.[2]

Even before the formal start of the war, Yorkshire became a key area in the conflict. After King Charles I attempted to arrest five members of parliament in January 1642, members of the gentry started openly taking sides and preparing for battle. Sir John Hotham seized Hull for parliament the same month, and after fleeing London, the King established himself at York in March. The King twice attempted to take Hull in 1642 without success. Although Charles subsequently returned south, his wife, Henrietta Maria (formally known as Queen Mary) had travelled to the Low Countries to obtain weapons and the Earl of Newcastle was charged with ensuring her safe travel through the northeast when she returned.[3] On the other side, Ferdinando Fairfax, 2nd Lord Fairfax of Cameron, was appointed as the commander of parliament's forces in Yorkshire.[4]

Newcastle's army of 6,000 reinforced York and gave the Royalists the advantage in the county;[5] the main Parliamentarian army had less than 1,000 men at the time, and was forced to retreat. They first withdrew to Tadcaster and then were forced back to Selby in the north of the county, cutting them off from their main support to the west. Sir Thomas Fairfax, Lord Fairfax's son, successfully stormed Leeds in January 1643 and regained the West Riding of Yorkshire for the Parliamentary side establishing strong garrisons at Bradford and Leeds.[6]

Prelude

[edit]While acting as the rearguard to the army under the command of his father, Sir Thomas Fairfax had been defeated by George Goring at the Battle of Seacroft Moor on 30 March 1643,[7] and 800 of his men had been captured. Under pressure from the families of those captured, Fairfax planned to surprise Royalist-held Wakefield, which he thought was held by no more than 900 men,[8] to capture sufficient men to trade for his own.[9]

When the Earl of Newcastle went on the attack to attempt and take all of south Yorkshire for the Royalists, he stationed Goring at Wakefield to protect against the Parliamentarian garrison at Leeds, held by the Fairfaxes.[8] On 20 May, the day before the attack, Goring and other senior Royalist officers in Wakefield were hosted by Dame Mary Bolles at her home, Heath Hall, to the east of the town. While playing bowls and other games, the Royalists "drank so freely ... as to be incapable of properly attending to the defence of the town."[10] Goring was well known for being a heavy drinker, something Sir Richard Bulstrode, his adjutant, substantiated.[11]

Battle

[edit]After an evening march on 20 May 1643, Parliamentarian forces from Bradford, Leeds and Halifax met at Howley Hall, to the northeast of Wakefield, at midnight. Reinforced with troops from Howley Hall, the Parliamentarians had around 1,500 men for the attack; 1,000 infantry and 500 horse. The horse were split into eight troops of cavalry and three troops of dragoons. Sir Thomas Fairfax had overall command of the force, while also leading four troops of the cavalry; the other four troops being under the command of Sir Henry Foulis. William Fairfax (Thomas's cousin) and George Gifford split the infantry, which comprised both pikemen and musketeers, between them.[a] At 2 am, the Parliamentarians surprised and overcame a Royalist outpost consisting of two troops of cavalry at Stanley, roughly 2.5 miles (4 km) from Wakefield.[13][14]

Fairfax's army arrived at Wakefield around two hours later, just before dawn.[15] Wakefield was not a walled, fortified town; the defences were made up of the hedges surrounding each property on the edge of town and barricades in the streets. The hedges provided a sufficient barrier against the attackers, and so the barricades became the focus of the fighting. As they were only the width of the road, this evened the battle, as although the garrison held more men, they could place only as many defenders as could fit at the barricade.[16] The defenders had been alerted to the enemy approach by the cavalry that had fled from Stanley, and had stationed between 500 and 800 musketeers in the surrounding hedges as well as sending a cavalry unit out to meet them.[15][17] The Parliamentarian infantry was able to displace the musketeers, and their larger force of horse drove the Royalist cavalry back into Wakefield.[17] Fairfax realised that the enemy garrison was far larger than he expected;[15] in fact, the defending garrison numbered around 3,000 Royalists, split into six infantry regiments and seven cavalry troops,[17] more than three times what Fairfax had expected. Despite this, after a short meeting with his fellow commanders, Fairfax opted to continue with the assault.[16]

Fairfax split his force to attack from two directions:[9] Foulis and William Fairfax attacked Northgate,[7] while Thomas Fairfax and Gifford attacked Warrengate, the eastern entrance to the town.[9] Writing years later, Newcastle's wife accused Goring and the Wakefield garrison of "inviligancy and carelessness" due to a belief that their numbers made them "master of the field in those parts".[17] After around two hours of fighting, Gifford's infantry battled their way through Warrengate, and were then able to capture a cannon and turn it on the barricade to clear enough room for the cavalry to break through. Thomas Fairfax then led three troops of cavalry into the town, routing the Royalist infantry along Warrengate.[9][18]

Goring was in bed ill: Royalist reports claimed that he had a fever. Modern historians vary in their accounts of his condition: in her 2007 biography of Goring, Florene S. Memegalos described him as being "sick in bed with a fever, attended by his father that weekend";[17] but others such as John Barratt (2005) and Richard Brooks (2004) suggest that he was hungover from the previous day's drinking.[9][15] Whatever his incapacity, he led a counterattack on horseback, "in his nightshirt" according to Brooks.[9] Despite his resistance, he and his guard were defeated, and Goring was taken prisoner by Lieutenant Alrud, though both his father, Lord Goring, and his deputy, Francis Mackworth, were able to escape.[9][17] Fairfax continued to press the attack, and was nearly captured when he found himself isolated from his men, and seemingly trapped in a side street by a Royalist infantry regiment. Fairfax was holding two prisoners, but the infantry commander ignored him and asked one of his prisoners for instructions. The prisoner gave no answer, holding to the terms of his capture, and Fairfax decided to abandon his prisoners and escaped down a narrow lane back to his men.[19]

Gifford, after opening the barricade, had the captured cannon moved to the churchyard of All Saints Church (now Wakefield Cathedral), where he turned it on the Royalists holding the marketplace. After offering the defenders a chance of surrender, which they rejected, his musketeers and the cannon opened fire, before the cavalry charged them. The remaining soldiers in the garrison gave up their resistance, either escaping or surrendering, and by 9 am, the Parliamentarians held the town.[20] They captured roughly 1,400 prisoners, including Goring, 28 Royalist colours and a large amount of much-needed ammunition.[7][9] According to Fairfax's account of the siege, his force lost "not above seven men", but did admit that "many of our men were shot and wounded."[21]

Aftermath

[edit]

As was typical during the Civil War, the Parliamentarians published an array of propaganda after the capture, claiming that their victory was the "work of God", while casting the Royalists as deceitful and ruinous. Accordingly, parliament declared 28 May a day of thanksgiving for the victory.[22] After capturing Wakefield, Fairfax was wary of an attack from the larger Royalist army that Newcastle commanded, and he immediately retreated back to Leeds with his prisoners. Instead of the expected retaliation, Newcastle withdrew his own forces to York.[23] Goring was imprisoned in the Tower of London, and despite attempts by the Royalists to secure his immediate exchange, he remained incarcerated until April 1644, when he was swapped for the Earl of Lothian.[24]

The primary objective of the attack was successful; an exchange was set up to recover the men Fairfax had lost at Seacroft Moor,[25] and the victory temporarily changed the balance of power in Yorkshire. The effect of the capture was negated just over a month later, when a Parliamentarian army under the command of Fairfax was defeated at Aldwalton Moor on 30 June 1643, which gave the Royalists control of much of Yorkshire.[7]

By the end of 1644, aided by Fairfax's decisive victory at Marston Moor, most of the north of England had been captured by Parliamentarian forces.[26] The following year, Fairfax was appointed as the commander-in-chief of parliament's forces, and established the so-called "New Model Army".[27] The army's victories, particularly at Naseby and Langport, gained parliament control of most of the rest of England.[26] Near Wakefield, Sandal Castle on the edge of the town had remained a Royalist garrison throughout the war despite the town's capture. The castle was in a state of disrepair, but had been reinforced with earthworks. The castle was twice besieged in 1645, surrendering to the Parliamentarians in October, and was subsequently slighted.[28] In May 1646, King Charles I surrendered, and the First English Civil War ended.[26]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Bennett 2005, p. xii.

- ^ Bleiberg & Soergel 2005, pp. 344–348.

- ^ Cooke 2006, pp. 128–133.

- ^ Hopper, Andrew J. (2008) [2004]. "Fairfax, Ferdinando, second Lord Fairfax of Cameron". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/9081. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Cooke 2006, p. 133.

- ^ Cooke 2006, pp. 136–138.

- ^ a b c d McKenna 2012, p. 303.

- ^ a b Barratt 2004, p. 99.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Brooks 2005, p. 415.

- ^ Wentworth 1864, pp. 260–261.

- ^ Memegalos 2007, p. 291.

- ^ Little 2014, p. 71.

- ^ Cooke 2004, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Memegalos 2007, p. 145.

- ^ a b c d Barratt 2004, p. 100.

- ^ a b Cooke 2004, p. 56.

- ^ a b c d e f Memegalos 2007, p. 146.

- ^ Cooke 2004, pp. 56–58.

- ^ Cooke 2004, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Cooke 2004, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Cooke 2004, p. 60.

- ^ Memegalos 2007, p. 147.

- ^ Cooke 2004, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Barratt 2004, pp. 100–101.

- ^ Cooke 2004, p. 63.

- ^ a b c Gaunt 1997, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Gentles, Ian J. (2008) [2004]. "Fairfax, Thomas, third Lord Fairfax of Cameron". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/9092. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Harrington 2004, p. 51.

Bibliography

[edit]- Barratt, John (2004). Cavalier Generals: King Charles I and His Commanders in the English Civil War 1642–1646. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 1-84415-128-X.

- Bennett, Martyn (2005). The Civil Wars Experienced: Britain and Ireland, 1638–1661. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-203-98180-4.

- Bleiberg, Edward; Soergel, Philip, eds. (2005). "The English Civil Wars". Arts and Humanities Through the Eras. Vol. 5: The Age of the Baroque and Enlightenment 1600–1800. Detroit: Gale. ISBN 978-0-787-65697-3.

- Brereton, William (2012). McKenna, Joseph (ed.). A Journal of the English Civil War: The Letter Book of Sir William Brereton, Spring 1646. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-7269-7.

- Brooks, Richard (2005). Cassell's Battlefields of Britain and Ireland. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-304-36333-2.

- Cooke, David (2004). The Civil War in Yorkshire: Fairfax Versus Newcastle. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 1-84415-076-3.

- Cooke, David (2006). Battlefield Yorkshire: From the Romans to the English Civil Wars. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 1-84415-424-6.

- Gaunt, Peter (1997). The British Wars 1637–1651. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-12966-4.

- Harrington, Peter (2004). English Civil War Archaeology. London: Batsford. ISBN 978-0-7134-8897-5.

- Little, Patrick (2014). The English Civil Wars: A Beginner's Guide. London: Oneworld Publications. ISBN 978-1-7807-4331-8.

- Memegalos, Florene S. (2007). George Goring (1608–1657): Caroline Courtier and Royalist General. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-5299-1.

- Wentworth, George (1864). "Heath Old Hall". Journal of the British Archaeological Association. 20. London: British Archaeological Association. OCLC 971084314.