Captain from Castile

| Captain from Castile | |

|---|---|

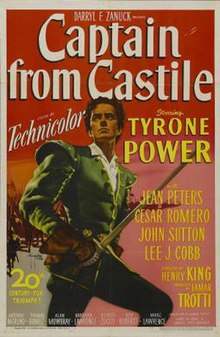

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Henry King |

| Screenplay by | Lamar Trotti |

| Based on | Captain from Castile 1945 novel by Samuel Shellabarger |

| Produced by | Lamar Trotti Darryl F. Zanuck (executive producer) |

| Starring | Tyrone Power Jean Peters Cesar Romero |

| Cinematography | Charles G. Clarke Arthur E. Arling Joseph LaShelle (uncredited) |

| Edited by | Barbara McLean |

| Music by | Alfred Newman |

| Distributed by | Twentieth Century-Fox Film Corporation |

Release date |

|

Running time | 141 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $4.5 million |

| Box office | $3,650,000 (US rentals)[1] |

Captain from Castile is a 1947 American historical adventure film. It was released by 20th Century-Fox. Directed by Henry King, the Technicolor film stars Tyrone Power, Jean Peters, and Cesar Romero. Shot on location in Michoacán, Mexico, the film includes scenes of the Parícutin volcano, which was then erupting. Captain from Castile was the feature film debut of Jean Peters, who later married industrialist Howard Hughes, and of Mohawk actor Jay Silverheels, who later portrayed Tonto on the television series The Lone Ranger.

The film is an adaptation of the 1945 best-selling novel Captain from Castile by Samuel Shellabarger. The film's story covers the first half of the historical epic, describing the protagonist's persecution at the hands of the Spanish Inquisition and his escape to the New World to join Hernán Cortés in an expedition to conquer Mexico.

Plot

[edit]In the spring of 1518, near Jaén, Spain, Pedro de Vargas, a Castilian caballero, helps a runaway Aztec slave, Coatl, escape his cruel master, Diego de Silva. De Silva is el supremo of the Santa Hermandad, charged with enforcing the Inquisition, and Pedro's rival for the affections of the beautiful Lady Luisa de Carvajal. Later, Pedro rescues barmaid Catana Pérez from de Silva's men. At the inn where Catana works, Pedro becomes acquainted with Juan García, an adventurer just returned from the New World to see his mother.

Suspecting Pedro of aiding Coatl, and aware that Pedro's influential father Don Francisco de Vargas opposes the abuses of the Santa Hermandad, de Silva imprisons Pedro and his family on the charge of heresy. Pedro's young sister dies under torture. Meanwhile, Juan becomes a prison guard to help his mother, also a prisoner. He kills her to spare her further torture. Juan frees Pedro's hands and gives him a sword.

When de Silva enters Pedro's cell, Pedro disarms him in a sword fight, then forces him to renounce God before stabbing him. The trio (secretly aided by Catana's brother, the sympathetic jailer Manuel) flee with Pedro's parents. Forced to split up, instead of going to Italy to be reunited with his family, Pedro is persuaded by Juan and Catana to seek his fortune in Cuba.

The three sign up with Hernán Cortés on his expedition to Mexico. Pedro tells Father Bartolomé, the spiritual adviser to the expedition, what occurred in Spain. The priest had received an order to arrest him, but tears it up and gives Pedro a penance, neither aware that de Silva survived.

The expedition lands at Villa Rica in Mexico.[2] Cortés is greeted by emissaries of Aztec Emperor Montezuma and given a bribe to leave. Cortés instead persuades his men to join him in his plan for conquest and riches.

Catana seeks the aid of charlatan and doctor Botello, who reluctantly gives her a ring with the supposed power to make Pedro fall in love with her, despite their vast difference in social status. When Pedro kisses her, she rejects him, believing he is under the ring's spell, but he convinces her otherwise and marries her that very night.

Cortés marches inland to Cempoala, where he receives a bribe of gems from another Aztec delegation. He places Pedro in charge of guarding the gems in a teocalli. Pedro leaves his post, however, to calm down drunk, menacing Juan, and the gems are stolen. Cortés accuses Pedro of theft. When Pedro finds a hidden door into the teocalli, Cortés gives him 24 hours to redeem himself. Pedro tracks the thieves, captains opposing Cortés, back to Villa Rica, where they have incited mutiny. With the aid of Corio, a loyal crewman, he recovers the gems, although he is seriously wounded in the head by a crossbow bolt during their escape.

Cortés promotes Pedro to captain. Then, to remove the temptation of retreat, he orders their ships burned. They march on to Cholula, where they are met by another delegation, led by Montezuma's nephew, who threatens the expedition with annihilation unless they leave. When Cortés protests that he has no ships, the prince reveals that more have arrived. Cortés realizes that his rival, Cuban Governor Velázquez, has sent a force to usurp his command. Cortés takes half his men to attack Villa Rica, leaving Pedro in command of the rest.

Cortés returns victorious, bringing with him reinforcements and Diego de Silva, the King's emissary. De Silva is there to impose the Santa Hermandad on Mexico. Juan attacks de Silva, but is stopped by Cortes' soldiers. Father Bartolomé reminds Pedro of his vow, and Cortés holds him personally responsible for de Silva's safety. When de Silva is strangled that night, Pedro is sentenced to death. Just before the execution, Coatl confesses to Father Bartolomé that he killed de Silva. Catana stabs him to spare him the degradation of being hanged. Pedro recovers, and Cortés and his followers march on the Aztec capital.

Cast

[edit]- Tyrone Power as Pedro de Vargas

- Jean Peters as Catana Pérez

- Cesar Romero as Hernán Cortés[3]

- Lee J. Cobb as Juan García

- John Sutton as Diego de Silva

- Antonio Moreno as Don Francisco de Vargas

- Thomas Gomez as Father Bartolomé de Olmedo

- Alan Mowbray as Professor Botello

- Barbara Lawrence as Luisa de Carvajal

- George Zucco as Marquis de Carvajal

- Roy Roberts as Capt. Pedro de Alvarado

- Marc Lawrence as Corio

- Robert Shaw as Spanish army officer (uncredited)

- Jay Silverheels as Coatl (uncredited)

- Stella Inda as La Malinche (uncredited)

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]Darryl F. Zanuck bought the rights to the novel in November 1944, prior to its publication but after it had been serialized in Cosmopolitan.[4] The purchase price was $100,000.[5]

It was the ninth novel Zanuck had purchased in as many months, the others being Keys of the Kingdom, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, Forever Amber, Leave Her to Heaven, Dragonwyck, Anna and the King of Siam, Razor's Edge and A Bell for Adano.[6]

Casting

[edit]Twentieth Century-Fox director-writer-producer Joseph L. Mankiewicz, consulting with executive producer Darryl F. Zanuck on the making of Captain from Castille, recommended a reunion of Tyrone Power and Linda Darnell for the lead roles of Pedro and Catana.[7]

However, Power was still in the army. In July 1945 Fox announced that the leads would be played by Cornel Wilde, a studio actor who had just leapt to fame in A Song to Remember, and Linda Darnell.[8]

By August 1945, however, Power was announced for the lead and Cornel Wilde was out.[9]

Power returned from service as a Marine Corps aviator during World War II and was available. Darnell was given the role of Catana, but appeared in two other projects while preparation for production was being completed.[10]

In the meantime, Zanuck began filming of Forever Amber with the inexperienced Peggy Cummins in the title role, investing $1 million in the project before realizing it had become a disaster. Darnell replaced Cummins to try to save the project, and the role of Catana went to the then unknown Jean Peters in November 1946.[11][12]

Other actors recommended by Mankiewicz but not cast were Fredric March as Cortés, José Ferrer as Coatl, and Alan Reed or William Bendix to play Juan García.[7]

Screenplay

[edit]In February 1945, studio contract writer John Tucker Battle produced an outline, then completed a first draft script with Samuel Engel in May. Zanuck consulted Joseph L. Mankiewicz about concepts for the film.

Mankiewicz wrote back to Zanuck in July that the historical background of Cortés' conquest of Mexico had to be both accurate and unoffending to many groups of people. Mankiewicz also warned that the story would be tremendously expensive to film: "To do this picture ambitiously will cost a great deal of money. It will require Technicolor, a huge cast, great numbers of people, elaborate sets, costumes, props, locations etc. The script will take a long time to write—thorough research will be necessary."[7]

In August 1946, Lamar Trotti was assigned to write the script and Henry King to direct.[13]

The original scripts and storyline included a scene involving one of the novel's major characters and villains, the Dominican fray/Inquisitor Ignacio de Lora, to be played by British character actor John Burton. De Lora's character conducted the "examination" of the de Vargas family, tortured Juan Garcia's mother, and dispatched the order for Pedro's arrest to Cuba. Citing a December 15, 1947 article in The New York Times, one source attributes the excision of the scene to censorship by the Rev. John J. Devlin, a representative of the National Legion of Decency and advisor to the Motion Picture Association of America, on the basis that the depiction of the Spanish Inquisition was unacceptable to the Catholic Church. After revision of the script "toned down" depictions of the Inquisition, changing its name from the Santa Casa (The Holy Office) to the Santa Hermandad, eliminating the auto de fe prominent in the book, and making the lay character of de Silva the chief Inquisitor, the script was acceptable to Devlin.[7]

Keeping the film at an acceptable length required moving events that took place in the book's second half, primarily the return of Coatl and demise of de Silva, backward to what became the film's finale.

Followers of the novel have criticized the failure to include the second half, which follows Pedro's development from a callow youth of 19 to a mature gentleman and features the expedition's battles with the Aztecs, Pedro's capture during the Noche Triste, his return to Spain and subsequent intrigue at the court of Charles V. However, like the film adaptation of Northwest Passage, the film's length and severe costs limited inclusion of those aspects most desired by the producers.

The script for similar reasons made minor alterations to relationships in the novel, eliminating Pedro's prior dalliances with Catana, helping Juan against the Inquisition before being persecuted, and combining the characters Humpback Nojara, surgeon Antonio Escobar, and Botello the Astrologer into a single person, "Professor Botello". Even so, the screenplay faithfully adapts the important plot elements and scenes from the novel.[14]

Historically, the most barbaric atrocities of Cortés are not depicted in the script. In particular, the slaughter of thousands of Aztecs in Cholula as a warning to Montezuma is instead shown as a single cannon shot demolishing an idol. The first review of the film in The New York Times noted that, while the novel seemed written with a Technicolor movie in mind, the action, horror, and bloodshed of the book were not translated to the film.[15]

The script, while employing Spanish terminology and names where appropriate, also uses an undisclosed indigenous dialect (likely Nahuatl) for dialogue involving the Aztecs, with the historical personage Doña Marina (portrayed by Mexican actress Estela Inda) providing the translation as she did in real life.

Other historically accurate characters portrayed were the mutineers Juan Escudero (John Laurenz) and Diego Cermeño (Reed Hadley), and the loyal captains Pedro de Alvarado (Roy Roberts) and Gonzalo de Sandoval (Harry Carter).[16]

Shooting

[edit]Filming began November 25, 1946, and was completed on April 4, 1947. Filming started in Morelia, west of Mexico City.[17]

Location filming took place in three locations in Mexico, two in the Mexican state of Michoacán. Acapulco provided ocean and beach locations for scenes involving "Villa Rica" (Veracruz).

In Michoacán, the hills around Morelia depicted the countryside of Castile for the first half of the film, while extensive shooting took place near Uruapan to depict the Mexican interior. There the volcano Parícutin, which had erupted in 1943 and was still active, was featured in the background of many shots of the Cholulu (Cholula) sequences. In 1519-1520, the volcano Popocatépetl, just to the west of Cholula, had also been active while the Cortés expedition was present.[18]

The film's final scene, involving the movement of the expedition and its thousands of Indian porters, was filmed on the edge of Parícutin's lava beds with the cinder cone prominently nearby in the shot.[7] The presence of the volcano, however, also proved to be expensive to production, since its ash cloud often made lighting conditions inconducive to filming.

The film made extensive use of Mexican inhabitants as extras. More than 19,500 took part in various scenes, with approximately 4,500 used in the final sequence filmed in front of Parícutin's smoking cinder cone.[7]

The film company spent 83 days in Mexico before returning to Hollywood in February to complete 33 days of studio filming, at a then "extravagant" cost of $4.5 million.[7][19][20]

Photography

[edit]In addition to the directors of photography credited onscreen, George E. Clarke and Arthur E. Arling, Clarke's protégé Joseph LaShelle also contributed to the filming of Captain from Castile. While LaShelle was noted for excellent black-and-white photography, particularly in film noir, he had little experience with Technicolor or location shooting. Clarke was competent at both. LaShelle's work in the film appears primarily in interior shots, notably in scenes at Pedro's home. Arling was mainly responsible for second unit filming under assistant director Robert D. Webb. On location, photography inside the temples proved difficult because of poor space for proper lighting and excessive heat that could degrade color film.[7]

Music

[edit]The lively musical score was composed by Alfred Newman, Fox's longtime musical director, and was nominated for an Academy Award. (The award went to A Double Life.) Newman recorded excerpts from the musical score for 78 rpm records (reportedly at his own expense), and donated his royalties to the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation.[7] Years after he re-recorded the score in stereo for Capitol Records. In 1973, Charles Gerhardt conducted a suite from the film for RCA Victor's tribute album to Newman, Captain from Castile; the quadraphonic recording was later reissued on CD.[citation needed]

Newman bestowed the rights to the film's final march on the University of Southern California to use as theme music for the school's football team. Popularly known as "Conquest"—sometimes "Trojan Conquest"—the march (arranged for a band) is regularly performed by its marching band, the Spirit of Troy, as a victory march.[7] It is also the corps anthem of the Boston Crusaders Drum and Bugle Corps, which has performed the piece in their field show frequently in the past and continues to incorporate it occasionally in their field shows of the present.[citation needed]

Reception

[edit]Though popular, the film failed to recoup its enormous cost.[21]

In his introduction to the 2002 re-issue of the novel, Pulitzer Prize–winning critic Jonathan Yardley described the film as:

a faithful adaptation that had all the necessary ingredients: an all-star cast, breathtaking settings and photography, a stirring score, and enough swashbuckling action to keep the Three Musketeers busy for years.[14]

It was nominated for the American Film Institute's AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores.[22]

Adaptations

[edit]A radio adaptation of Captain from Castile was aired on Lux Radio Theatre on February 7, 1949, with Cornel Wilde as Pedro and Jean Peters reprising her role. An adaptation starring Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. was broadcast on the Screen Directors' Playhouse on May 3, 1951.[7]

References

[edit]- ^ "Top Grossers of 1948", Variety, January 5, 1949, p. 46

- ^ Spellings and names of locations in Mexico along Cortés' route, as listed here, are those depicted in the film by use of an animated map.

- ^ The script uses the spelling "Hernán Cortez". For the use of the given name "Hernando", see Hernán Cortés#Name

- ^ "Captain from Castile - Review". TV Guide. Retrieved April 21, 2009. Cosmopolitan in 1945 featured fiction as its format.

- ^ Brady, Thomas F. (November 24, 1946). "Hollywood: Censoring of 'Bedelia' Has Amusing Results Arbiter Goes Home Heading South". The New York Times. p. 85.

- ^ Scheuer, Philip K. (December 1, 1944). "Darryl Zanuck to Film 'Captain From Castile': Warners Award Robert Hutton Lead in Recently Purchased 'Time Between'". Los Angeles Times. p. 11.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Captain from Castile". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved April 21, 2009. See "Notes", which quotes production and legal memos associated with film.

- ^ "Darnell Gets Role in Film on Mexico: Will Appear With Cornel Wilde in 'Captain From Castile'-- Fox Drama to Open Here". The New York Times. July 14, 1945. p. 5.

- ^ "Fox Plans Musical Based on 'Ramona': Deal Pending for Rudolf Friml to Write the Score--Three New Films Due Here". The New York Times. August 20, 1945. p. 22.

- ^ Davis, Ronald L. (2001). Hollywood Beauty: Linda Darnell and the American Dream. University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 0-8061-3330-9, p. 90.

- ^ Davis (2001), p. 96.

- ^ Millier, Arthur (November 10, 1946). "Unknown 20-Year-Old Wins Prize Screen Role: 'Find' Will Play Big 'Castile' Part With Ty Power". Los Angeles Times. p. B1.

- ^ "Lynn Bari Named for RKO Film Lead: Will Star Opposite George Raft in 'Nocturne,' Mystery Story --'Open City' Held Over Of Local Origin". The New York Times. April 30, 1946. p. 17.

- ^ a b Jonathan Yardley, "Introduction", page 1. Shellabarger, Samuel (1945, 2002). Captain from Castile, First Bridge Works Publishing. ISBN 1-882593-62-6.

- ^ "Captain from Castile at the Rivoli". The New York Times. December 26, 1947. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

- ^ Cortés, Hernán (author); Padgen, Dr. Anthony (translator, editor). (2001). Hernán Cortés: Letters from Mexico, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-09094-3, pp. 51 and 125.

- ^ Daugherty, Frank (December 20, 1946). "'Captain From Castile' On Location in Mexico". The Christian Science Monitor. p. 4.

- ^ Cortés and Padgen (2001), p. 77-78.

- ^ "Captain from Castile". AllMovie. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

- ^ Brady, Thomas F. (February 27, 1947). "Grant Will Star in Drama for RKO: Actor Takes Role in 'Weep No More,' to Be Done This Year --Endfield Writing Film". The New York Times. p. 26.

- ^ Memo from Darryl F Zanuck to Henry King, October 20, 1949, Memo from Darryl F. Zanuck, Grove Press 1993, p. 164

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-08-06.

External links

[edit]- 1947 films

- 1940s historical adventure films

- Films about conquistadors

- Films based on American novels

- Films directed by Henry King

- Films set in the 1510s

- Films set in Mesoamerica

- Films scored by Alfred Newman

- Films with screenplays by Lamar Trotti

- Cultural depictions of Hernán Cortés

- American historical adventure films

- 20th Century Fox films

- 1940s English-language films

- 1940s American films

- English-language historical adventure films