Canwell Committee

The Interim Committee on Un-American Activities or Joint Legislative Fact-Finding Committee on Un-American Activities, most commonly known as the Canwell Committee (1947–1949), was a special investigative committee of the Washington State Legislature which in 1948 investigated the influence of the Communist Party USA in the state of Washington. Named after its chairman, Albert F. Canwell, the committee concentrated on communist influence in the Washington Commonwealth Federation and its relationship to the state Democratic Party, and the alleged Communist Party membership of faculty members at the University of Washington in Seattle.

The Canwell Committee is remembered as one of a number of state-level investigative committees patterned after the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) of the United States Congress. The committee ultimately published two printed volumes collecting the testimony of witnesses before it. The committee was terminated by the Washington legislature in 1949, following the electoral defeat of its chairman and several of its members in the 1948 elections.

Background

[edit]

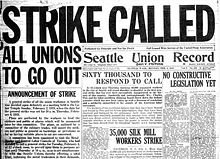

Becoming a state only in 1889, Washington was a relative latecomer to the United States. Although the Republican Party would control the state government for the next four decades, a frontier radicalism was prevalent in the region.[1][2][3] During the pre-World War I progressive era, local lumber workers joined the Industrial Workers of the World, leading to a successful 1917 lumber strike, the 1916 Everett massacre and the 1919 Centralia massacre.[4] Although the Socialist Party of Washington was disbanded in 1909 following a decision of the national executive committee of the Socialist Party of America, many socialists continued to live and work in the state.[2] Seattle was the site of a 1919 general strike which reinforced the national view of the state, particularly its labor movement, as radical.[5][6] The Farmer–Labor Party received significant support from Washington voters in the 1920 election,[7] as did progressive presidential candidate Robert M. La Follette's 1924 campaign.[citation needed] The state's national reputation for a left-of-center political climate was demonstrated by a quip by then-Postmaster General, James Farley, that the United States consisted of "forty-seven states and the Soviet of Washington."[8]

The Communist Party first appeared on a statewide ballot in 1928 and five years later, Seattle mayor John F. Dore denounced local political candidates, Marion Zioncheck and John C. Stevenson, as communists.[9] In 1935, a number of local groups – including the Commonwealth Builders, local chapters of the Workers Alliance of America, trade unions, technocrats and local Townsend clubs – banded together to form the Washington Commonwealth Federation (WCF), described as a "triple alliance of Liberals, Labor and Farm".[10] The organization endorsed Democratic and independent candidates in statewide and municipal elections, including Hugh De Lacy, a professor at the University of Washington. Although communists were officially banned from membership in the WCF, De Lacy's endorsement by the organization later fuelled concerns about communists at the university.[11]

There began to be tensions among left-leaning organizations and individuals during the late 1930s. A rivalry between top leaders Dave Beck and Harry Bridges became marred in anti-communist rhetoric in 1937, with Beck labelling Bridges "Red Harry". The same year, the Washington Pension Union (WPU) was established by state senator James T. Sullivan, a member of the WCF, as a campaigning group when the issue of raising pensions was ignored by the Democratic governor and legislature. Governor Clarence D. Martin also angered the WCF for his role in the 1939 dismissal of Charles H. Fisher, president of the Western Washington College of Education, for charges advanced by conservative reporter Frank Ira Sefrit that included allowing members of "subversive organizations" to speak on campus.[12]

Concerns amongst Democrats about the communist influences on their party were growing.[13] In winter 1939, the University of Washington received similar criticisms to Fisher, particularly for inviting Harold Laski, a British Marxist, to speak on campus. Although no further action was taken, state senator Joseph Drumheller threatened to investigate the university.[14][15] The Democratic attorney general, Smith Troy, asked the secretary of state to refuse the nominations of Communist Party candidates, a decision which was only overturned by the Washington Supreme Court. In 1940, following his resignation as president of the WPU, Sullivan joined with Drumheller in a Senate investigatory committee to determine whether the WPU's vice president, state senator Lenus Westman, was a communist.[16] The 1946 state elections saw Republicans position themselves as running against the communist-aligned Democrats, particularly a group of legislators affiliated with the WCF. In an illustration of the Republican sweep, De Lacy was replaced by a former leader of the American Legion, Homer Jones, as voters elected a Republican senator and Republican-controlled state legislature. Following the election, state Democrats, led by Troy, Drumheller, Beck and state senator Earl Coe, vowed to investigate their party to expel any suspected communists.[17][18]

Foundation

[edit]Prior to the 1947 legislative session, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer reported in December 1946 that Republicans and a group of coalition Democrats had met to discuss an investigation into communism in the Democratic Party. House Concurrent Resolution No. 10 was quickly introduced in the Washington House of Representatives by two freshmen legislators, Albert F. Canwell and Sydney A. Stevens.[19][20] The legislation – following the same structure as a 1945 California resolution establishing the Joint Fact-Finding Committee on Un-American Activities – was said to have been drafted by Canwell, although prosecuting attorney Charles O. Carroll later claimed that Post-Intelligencer reporter Fred Niendorff had told him that he was the author of the bill.[21]

Canwell had run for office on an anti-communist platform and upon entering office, he began coordinating with the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) by requesting copies of files created by its investigations into Washington residents.[22] The bill established a Joint Legislative Fact-Finding Committee on Un-American Activities to investigate individuals and organizations aiming to undermine the stability of American institutions, specifically "whose membership includes persons who are Communists, or any other organization known or suspected to be dominated or controlled by a foreign power."[23][24] Drafted as a concurrent resolution, it granted the committee the power to hold public hearings between the adjournment of the 1947 legislative session, reporting to the 1949 legislature.[25] The measure was introduced in the Washington State Senate by Democrat Thomas H. Bienz.[26]

The concurrent resolution passed the House of Representatives on March 3, 1947, receiving 86 yes votes, 8 no votes and 5 abstentions.[20] There was much reference in the debates to a peoples' march organized by the WPU that had occurred two days before. At the time the Senate was considering the resolution, in a hearing before the Senate committee on higher education, two candidates to be appointed as regents of the University of Washington denied that "subversive activities" were taught by university faculty. Their appointments were opposed by Bienz, who claimed that he had seen reports of as many as 30 professors teaching subversive activities.[27][28] A few days later, a Senate committee chaired by Bienz recommended the concurrent resolution and it passed the Senate on March 8, 1947, receiving 33 yes votes, 12 no votes and 1 abstention.[20][29]

The committee was made of up five Republicans and two Democrats, with a mix of representatives and senators.[26] House Speaker Herbert M. Hamblen appointed Canwell as chair.[30] The other Republican members were Stevens, Grant C. Sisson, R. L. Rutter Jr., and Harold G. Kimball. The two Democrats were Bienz, a supporter of the investigation, and George F. Yantis, who had been appointed by Hamblen to moderate the committee. However, Yantis died in December 1947, before the committee began its public hearings.[26]

Public reaction

[edit]Although most politicians refused to comment on the formation of the committee, Troy publicly voiced support for its mission. The WPU and a nascent local chapter of the Progressive Citizens of America publicly opposed the committee and proposed a state referendum on the creation of the committee until the state supreme court ruled that a concurrent resolution could not be the subject of a referendum.[31][32] At the University of Washington, students in the American Youth for Democracy created a committee on academic freedom to protest the Canwell Committee.[31]

First hearings

[edit]Investigations

[edit]Following the adjournment of the legislature, the Canwell Committee decided to delegate the investigation to a staff supervised by Canwell. He traveled to Washington, D.C. to speak with HUAC and then opened an office in the Seattle Armory in April 1947. The committee had a staff of seven, led by the investigators William J. Houston and John W. Whipple, which carried out a five month investigation. The committee kept a low profile during this time, with the exception of a comment by Canwell on the infiltration of communists in the national defence and public schools.[33] It had been indicated in March 1947 that the University of Washington would be a focus of the committee, prompting university president Raymond B. Allen to write the committee offering the university's full cooperation. One senior member of staff later testified that he had warned Allen at the time of this letter that there were several members of the Communist Party on the faculty.[34]

Beginning in October 1947, there were an increase in stories about communist activities appearing in the local Seattle newspapers. An international vice president of the Building Service Employees International Union, Jess Fletcher, had accused officers of the union of radicalism in January and, by October, had been subpoened by the Canwell Committee to discuss communism within the union. Reports into further allegations of communism within the union's Local No. 6 continued throughout the month, including that multiple employees had been fired.[35]

On January 11, 1948, Canwell Committee announced that it would convene its first hearings on subversion within the WPU at the Seattle Armory. The WPU responded by bringing a claim in the King County Superior Court to prevent the hearings and filed a separate order to show cause on Stevens and Kimball, temporarily barring them from sitting on the committee. On January 31, the court ruled that a legislative committee could not function when the legislature was adjourned but, as no officers of the WPU had been subpoenaed, it could not issue an injunction.[36] The WPU brought separate legal proceedings, seeking to prevent the Washington State Auditor from issuing payroll warrants for the committee's expenses. Russell Fluent, the state treasurer, agreed with the position and declared that his office would not pay the warrants, as the court had held that a legislative committee could not function during adjournment. In response, Canwell filed an action with the state supreme court to order payment of the committee's expenses. The court sided with Canwell, ruling that a legislative interim committee created by concurrent resolution could operate between legislative sessions. The WPU applied to the United States Supreme Court, which denied the petition to review.[37]

Hearings (January 27 – February 5, 1948)

[edit]While waiting for the court ruling, Canwell commenced the hearings as scheduled on January 27.[38] The aim of the hearings was to prove the WPU was subversive and its members were communists.[39] The Canwell Committee called local and national witnesses, who were not permitted to be cross-examined by defense lawyers.[40] The president of the WPU, William Pennock, was thrown out of the hearings on the first morning when he attempted to read a statement. The first witness was the former editor of the Daily Worker, Louis Budenz, who testified that it had been reported within the Communist Party that they had successfully infiltrated the WPU and two WCF publications were communist-controlled. He named De Lacy, Pennock, Bridges, Thomas Rabbitt, Richard Seller and Sarah Eldredge as members of the Communist Party, and testified that the Seattle Labor School was communist, the International Workers Order and the Robert Marshall Foundation were under communist influence and University of Washington professor Ralph Gundlach "follow[ed] the Party Line".[40][41] Two other former party members, Manning Johnson and Joseph Kornfeder, corroborated Budenz's testimony that the Communist Party's national committee had successfully infiltrated the WPU and named Jerry J. O'Connell as a party member.[42] There was also testimony from George Levich and Sonia Simone.[43]

Local witnesses who had been members of the Communist Party testified before their committee, often about their connections to the WPU or WCF, naming those who they claimed had been fellow members of the party. Former representative Kathryn Fogg testified that Gundlach and fellow professors Joseph Butterworth, Harold Eby, and De Lacy had been members of the party.[40] Sullivan, as founder of the WPU, testified that the union was taken under communist control in 1939 when the Workers Alliance was dissolved and Pennock and John Caughlan joined the WPU. He also said the Building Service union had been involved in the communist infiltration of the WPU, specifically naming William Dobbins.[44] Other members of the WPU and the WCF testified similarly, with representative H. C. Armstrong naming fellow politicians Fogg, Rabbitt, Pennock, Ernest Olson, Ellsworth Wills and N. P. Atkinson.[45] Howard Costigan testified that the WCF had been infiltrated by communists after 1936.[46] Eldredge named Burton James and Florence Bean James, directors of the Seattle Repertory Playhouse, as being closely affilitated with the party.[47] The final witness was Agnes Bridges, the ex-wife of Harry Bridges, who testified that her ex-husband was a member of the Communist Party.[48][note 1] Following her testimony, Canwell stated that anyone could choose to testify, although he had refused requests from the American Youth for Democracy as he felt their communist origin was sufficiently obvious, and the hearings on the WPU would be recessed.[50]

Second hearings

[edit]Investigations

[edit]The University of Washington's public relations committee met with the faculty senate in February 1948 to recommend that the university avoid publicity surrounding the Canwell Committee and to provide support where required. It became clear by late March, however, that the committee planned to investigate the university following a statement made by Bienz that there were "probably not less than 150 on the faculty who are Communists or sympathizers with the Communist party".[51][52] Although Canwell disputed the comments, saying they could not yet provide a figure, the majority of the university's Board of Regents were prepared to fire any faculty member found to be engaged in subversive activities, which they communicated to Canwell at a meeting on April 22. In response, Canwell agreed to postpone the hearings until the end of the spring quarter and to provide Allen with details of the charges prior to the hearing so the university could investigate internally.[53]

In early June, Canwell gave Allen a list of the seven faculty members who the committee believed were or had been members of the Communist Party, along with the 33 faculty members who would be subpoenaed during the hearing as witnesses. Allen told the regents that following the hearings, a special committee of the faculty senate would determine if any members of staff should face charges before the faculty committee on tenure and academic freedom. In a press statement, Canwell further said that should any faculty refuse to testify, they could face contempt charges. The president of the university chapter of the American Association of University Professors, R. G. Tyler, spoke with the subpoenaed faculty prior to the hearing to offer the university's support of past members of the party if they were honest on the stand.[54] Some faculty members doubted this, believing that some of the accused would be fired regardless of the university's stated position, and a group of nine professors announced on June 30 that they would not respond to the subpoenas. This group included Gundlach, Butterworth and Herbert J. Phillips, although Gundlach later decided to testify.[55] Apart from the faculty, subpoenas were also served on the Jameses, actor Albert Ottenheimer, university counselor Ted Astley, former fellow Philip Hunt Davis and city sanitation inspector Rachmiel Forschmiedt.[56]

The investigations encountered opposition from the newly formed Washington Committee for Academic Freedom, a group of roughly one hundred professors, members of the American Civil Liberties Union and prominent liberals including Stimson Bullitt, Max Savelle, Kenneth MacDonald and Benjamin H. Kizer. The Canwell Committee was also opposed by the Students for Wallace, the Washington Young Progressives and Local 401 of the American Federation of Teachers.[57][58]

Hearings (July 19 – July 24, 1948)

[edit]Beginning on July 19, 1948, the Canwell Committee held its second hearings on the subject of subversion within the University of Washington.[59] Witnesses included George Hewitt, who claimed he had taught University of Washington professor Melvin Rader at a "highly secret Communist school at Briehl's Farm, near Kingston, New York, for a period of about six weeks in the Summer of 1938 or 1939." Rader later pursued Hewitt for perjury.[60]

Canwell also invited anti-communists Howard Rushmore and J. B. Matthews to testify before the committee about Alger Hiss. Alger Hiss had not yet been prosecuted.[30][61] Rushmore testified for three days including testimony about more than a dozen members of the Communist Party arrested following the federal investigations). Rushmore also claimed that "moles" existed in the federal government. He named Harold Ware, Lee Pressman, Donald Hiss, John Abt, Charles Kramer, Nathan Gregory Silvermaster, and Joseph P. Lash. Fred Neindorff of the Seattle Post Intelligencer and Ashley Holden of the Spokesman-Review both covered the story; U.S. Secretary of State George C. Marshall personally called both newspapers to quash the story.[62][63]

During taping for an oral history in 1997, Canwell said, "We wished to put the Hiss case in the record, and there's testimony by them about atomic scientists and others who were questionable characters." The only scientist whose name Canwell could remember was J. Robert Oppenheimer of the Manhattan Project. "There were numerous others," Canwell said, but he would have to go back and read the record to call "all their names" accurately. Asked to "characterize" Oppenheimer, Canwell said he agreed with conservative journalist Westbrook Pegler: he paid dues in the Communist Party, he was married to a communist, and sleeping with at least one other one. Of the two, Rushmore and Matthews, Canwell explained, "Rushmore was principally brought out to testify on Hiss and the atomic scientists," while Matthews helped on the subject of universities.[30]

Dissolution

[edit]In November 1948, Canwell lost his re-election; the committee issued its final report in January 1949.[30]

Publications

[edit]- Albert F. Canwell, et al., First Report, Un-American Activities in Washington State, 1948. Olympia, WA: The committee, 1948.

- Albert F. Canwell, et al., Second Report, Un-American Activities in Washington State, 1948. Olympia, WA: The committee, 1948.

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Countryman 1951, p. 1.

- ^ a b Johnson 2014, p. 4.

- ^ Cravens 1966, p. 148.

- ^ Countryman 1951, p. 2.

- ^ Cravens 1966, p. 149.

- ^ McRoberts, Patrick (March 5, 2003). "Seattle General Strike begins on February 6, 1919". HistoryLink. Retrieved August 16, 2023.

- ^ Cravens 1966, pp. 156–157.

- ^ Sanders 1979, p. 7.

- ^ Countryman 1951, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Countryman 1951, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Countryman 1951, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Countryman 1951, pp. 5–8.

- ^ Countryman 1951, p. 8.

- ^ Sanders 1979, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Wilma, David (January 1, 2000). "State Representative criticizes UW for hiring Marxist Harold Laski as visiting lecturer on January 23, 1939". HistoryLink. Retrieved August 16, 2023.

- ^ Countryman 1951, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Sanders 1979, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Countryman 1951, pp. 10–12.

- ^ Countryman 1951, pp. 13–14.

- ^ a b c Lange, Greg (July 10, 1999). "Washington State Legislature passes the Un-American Activities bill on March 8, 1947". HistoryLink. Retrieved August 15, 2023.

- ^ Countryman 1951, pp. 13–14, 292–293.

- ^ Sanders 1979, p. 21.

- ^ Countryman 1951, p. 14.

- ^ Wick, Nancy (December 1997). "Seeing Red: Fifty Years Ago, a Hearing on "Un-American" Activities Tore the UW Campus Apart, Setting a Precedent for Faculty Firings across Academe". Columns. University of Washington. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ Countryman 1951, p. 15.

- ^ a b c Sanders 1979, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Sanders 1979, p. 16.

- ^ Countryman 1951, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Countryman 1951, pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b c d Canwell, Albert F.; Frederick, Timothy (1997). "Albert F. Canwell: An Oral History" (PDF). Washington State Oral History Program. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ a b Sanders 1979, p. 22.

- ^ Countryman 1951, p. 19.

- ^ Countryman 1951, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Sanders 1979, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Countryman 1951, pp. 25–28.

- ^ Countryman 1951, p. 34.

- ^ Countryman 1951, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Countryman 1951, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Sanders 1979, p. 23.

- ^ a b c Sanders 1979, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Countryman 1951, pp. 34–38.

- ^ Countryman 1951, pp. 38–40.

- ^ Countryman 1951, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Countryman 1951, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Countryman 1951, pp. 43–46.

- ^ Countryman 1951, p. 49.

- ^ Countryman 1951, p. 52.

- ^ Countryman 1951, p. 64.

- ^ Countryman 1951, p. 66.

- ^ Countryman 1951, p. 65.

- ^ Sanders 1979, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Lange, Greg (July 10, 1999). "University of Washington sees Red and fires three faculty members on January 22, 1949". HistoryLink. Retrieved August 16, 2023.

- ^ Sanders 1979, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Sanders 1979, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Sanders 1979, p. 36.

- ^ Countryman 1951, p. 75.

- ^ Sanders 1979, p. 37.

- ^ Countryman 1951, p. 74.

- ^ Countryman 1951, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Rader, Melvin (July 5, 1954). "The Profession of Perjury". The New Republic. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ "Politics: Senator McCarthy gets a break". Life. 28 August 1950. p. 103. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ Kienholz, M. (21 September 2012). The Canwell Files: Murder, Arson and Intrigue in the Evergreen State. iUniverse. pp. 85–86. ISBN 9781475948813. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ Kershner, Jim (July 28, 2011). "Canwell, Albert F. (1907-2002)". HistoryLink.org. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

Sources

[edit]- Countryman, Vern (1951). Un-American Activities in the State of Washington. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1117931128.

- Cravens, Hamilton (1966). "The Emergence of the Farmer-Labor Party in Washington Politics, 1919-20". The Pacific Northwest Quarterly. 57 (4): 148–157. ISSN 0030-8803. JSTOR 40488173.

- Johnson, Jeffrey A. (2014). "They Are All Red Out Here": Socialist Politics in the Pacific Northwest, 1895–1925. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-8580-4.

- Sanders, Jane (1979). Cold War on Campus: Academic Freedom at the University of Washington, 1946-64. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295956527.

Further reading

[edit]- Albert F. Canwell and Timothy Frederick, Albert F. Canwell: An Oral History, Olympia, WA: Washington State Oral History Program, Office of the Secretary of State, 1997.

- Vern Countryman, "Washington: The Canwell Commission," in Walter Gellhorn (ed.), The States and Subversion. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1952; pp. 283–357.

- Melvin Rader, False Witness. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 1969.

- Susan Gilmore, "The Cold War And Albert Canwell: The 1948 Anti-Communist Hearings Earned The Freshman Legislator An Instant Reputation — And Shattered Lives," Seattle Times, Aug. 2, 1998.

- Schrecker, Ellen (1986). No Ivory Tower: McCarthyism and the Universities. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195035577.

External links

[edit]- James Gregory (general editor), "Special Section: Canwell Hearings" Communism in Washington State: History and Memory, University of Washington, 2009–2012. Including complete, digitized transcripts of the hearings, historical photographs, documents and essays.

- Register of Richard Gladstein Papers, 1930–1969 at the Southern California Library for Social Studies and Research

- Albrt M. Ottenheimer Papers, 1935–1980 at the University of Oregon Special Collections and University Archives

- University of Washington - Photos

- Finding aids at the University of Washington Libraries Special Collections:

- Ted Astley Papers . 1920–1994. 1.42 cubic ft. (2 boxes and 3 photographs).

- John S. Daschbach Papers.1936-1957. 3.78 cubic ft. (9 boxes).

- Garland O. Ethel Papers. 1913–1980. 13.00 cubic ft. (13 boxes).

- Ralph H Gundlach Papers. 1918–1974. 1.47 cubic ft. (4 boxes).

- Washington Committee for Academic Freedom Records. 1947–1948. .84 cubic ft. (2 boxes).

- Howard Costigan Papers.1933-1989. 6 Cubic ft. (6 boxes and 1 package).

- Thomas C. Rabbit Papers. 1943–1961. .42 Cubic ft. (1 box).

- Charles M. Gates Papers. 1881–1963. 24.84 cubic ft.

- Melvin Jacobs Papers. 1918-1974 78.23 cubic ft.

- John Caughlan Papers. 1933–1999. 54.44 cubic feet (85 boxes, 3 oversize folders and 2 vertical files).