Cancer epigenetics

Cancer epigenetics is the study of epigenetic modifications to the DNA of cancer cells that do not involve a change in the nucleotide sequence, but instead involve a change in the way the genetic code is expressed. Epigenetic mechanisms are necessary to maintain normal sequences of tissue specific gene expression and are crucial for normal development.[1] They may be just as important, if not even more important, than genetic mutations in a cell's transformation to cancer. The disturbance of epigenetic processes in cancers, can lead to a loss of expression of genes that occurs about 10 times more frequently by transcription silencing (caused by epigenetic promoter hypermethylation of CpG islands) than by mutations. As Vogelstein et al. points out, in a colorectal cancer there are usually about 3 to 6 driver mutations and 33 to 66 hitchhiker or passenger mutations.[2] However, in colon tumors compared to adjacent normal-appearing colonic mucosa, there are about 600 to 800 heavily methylated CpG islands in the promoters of genes in the tumors while these CpG islands are not methylated in the adjacent mucosa.[3][4][5] Manipulation of epigenetic alterations holds great promise for cancer prevention, detection, and therapy.[6][7] In different types of cancer, a variety of epigenetic mechanisms can be perturbed, such as the silencing of tumor suppressor genes and activation of oncogenes by altered CpG island methylation patterns, histone modifications, and dysregulation of DNA binding proteins. There are several medications which have epigenetic impact, that are now used in a number of these diseases.

Mechanisms

[edit]DNA methylation

[edit]

In somatic cells, patterns of DNA methylation are in general transmitted to daughter cells with high fidelity.[8] Typically, this methylation only occurs at cytosines that are located 5' to guanosine in the CpG dinucleotides of higher order eukaryotes.[9] However, epigenetic DNA methylation differs between normal cells and tumor cells in humans. The "normal" CpG methylation profile is often inverted in cells that become tumorigenic.[10] In normal cells, CpG islands preceding gene promoters are generally unmethylated, and tend to be transcriptionally active, while other individual CpG dinucleotides throughout the genome tend to be methylated. However, in cancer cells, CpG islands preceding tumor suppressor gene promoters are often hypermethylated, while CpG methylation of oncogene promoter regions and parasitic repeat sequences is often decreased.[11]

Hypermethylation of tumor suppressor gene promoter regions can result in silencing of those genes. This type of epigenetic mutation allows cells to grow and reproduce uncontrollably, leading to tumorigenesis.[10] The addition of methyl groups to cytosines causes the DNA to coil tightly around the histone proteins, resulting in DNA that can not undergo transcription (transcriptionally silenced DNA). Genes commonly found to be transcriptionally silenced due to promoter hypermethylation include: Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p16, a cell-cycle inhibitor; MGMT, a DNA repair gene; APC, a cell cycle regulator; MLH1, a DNA-repair gene; and BRCA1, another DNA-repair gene.[10][12] Indeed, cancer cells can become addicted to the transcriptional silencing, due to promoter hypermethylation, of some key tumor suppressor genes, a process known as epigenetic addiction.[13]

Hypomethylation of CpG dinucleotides in other parts of the genome leads to chromosome instability due to mechanisms such as loss of imprinting and reactivation of transposable elements.[14][15][16][17] Loss of imprinting of insulin-like growth factor gene (IGF2) increases risk of colorectal cancer and is associated with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome which significantly increases the risk of cancer for newborns.[18] In healthy cells, CpG dinucleotides of lower densities are found within coding and non-coding intergenic regions. Expression of some repetitive sequences and meiotic recombination at centromeres are repressed through methylation [19]

The entire genome of a cancerous cell contains significantly less methylcytosine than the genome of a healthy cell. In fact, cancer cell genomes have 20-50% less methylation at individual CpG dinucleotides across the genome.[14][15][16][17] CpG islands found in promoter regions are usually protected from DNA methylation. In cancer cells CpG islands are hypomethylated [20] The regions flanking CpG islands called CpG island shores are where most DNA methylation occurs in the CpG dinucleotide context. Cancer cells are deferentially methylated at CpG island shores. In cancer cells, hypermethylation in the CpG island shores move into CpG islands, or hypomethylation of CpG islands move into CpG island shores eliminating sharp epigenetic boundaries between these genetic elements.[21] In cancer cells "global hypomethylation" due to disruption in DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) may promote mitotic recombination and chromosome rearrangement, ultimately resulting in aneuploidy when the chromosomes fail to separate properly during mitosis.[14][15][16][17]

CpG island methylation is important in regulation of gene expression, yet cytosine methylation can lead directly to destabilizing genetic mutations and a precancerous cellular state. Methylated cytosines make hydrolysis of the amine group and spontaneous conversion to thymine more favorable. They can cause aberrant recruitment of chromatin proteins. Cytosine methylations change the amount of UV light absorption of the nucleotide base, creating pyrimidine dimers. When mutation results in loss of heterozygosity at tumor suppressor gene sites, these genes may become inactive. Single base pair mutations during replication can also have detrimental effects.[12]

Histone modification

[edit]Eukaryotic DNA has a complex structure. It is generally wrapped around special proteins called histones to form a structure called a nucleosome. A nucleosome consists of 2 sets of 4 histones: H2A, H2B, H3, and H4. Additionally, histone H1 contributes to DNA packaging outside of the nucleosome. Certain histone modifying enzymes can add or remove functional groups to the histones, and these modifications influence the level of transcription of the genes wrapped around those histones and the level of DNA replication. Histone modification profiles of healthy and cancerous cells tend to differ.

In comparison to healthy cells, cancerous cells exhibit decreased monoacetylated and trimethylated forms of histone H4 (decreased H4ac and H4me3).[22] Additionally, mouse models have shown that a decrease in histone H4R3 asymmetric dimethylation (H4R3me2a) of the p19ARF promoter is correlated with more advanced cases of tumorigenesis and metastasis.[23] In mouse models, the loss of histone H4 acetylation and trimethylation increases as tumor growth continues.[22] Loss of histone H4 Lysine 16 acetylation (H4K16ac), which is a mark of aging at the telomeres, specifically loses its acetylation. Some scientists hope this particular loss of histone acetylation might be battled with a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor specific for SIRT1, an HDAC specific for H4K16.[10][24]

Other histone marks associated with tumorigenesis include increased deacetylation (decreased acetylation) of histones H3 and H4, decreased trimethylation of histone H3 Lysine 4 (H3K4me3), and increased monomethylation of histone H3 Lysine 9 (H3K9me1) and trimethylation of histone H3 Lysine 27 (H3K27me3). These histone modifications can silence tumor suppressor genes despite the drop in methylation of the gene's CpG island (an event that normally activates genes).[25][26]

Some research has focused on blocking the action of BRD4 on acetylated histones, which has been shown to increase the expression of the Myc protein, implicated in several cancers. The development process of the drug to bind to BRD4 is noteworthy for the collaborative, open approach the team is taking.[27]

The tumor suppressor gene p53 regulates DNA repair and can induce apoptosis in dysregulated cells. E Soto-Reyes and F Recillas-Targa elucidated the importance of the CTCF protein in regulating p53 expression.[28] CTCF, or CCCTC binding factor, is a zinc finger protein that insulates the p53 promoter from accumulating repressive histone marks. In certain types of cancer cells, the CTCF protein does not bind normally, and the p53 promoter accumulates repressive histone marks, causing p53 expression to decrease.[28]

Mutations in the epigenetic machinery itself may occur as well, potentially responsible for the changing epigenetic profiles of cancerous cells. The histone variants of the H2A family are highly conserved in mammals, playing critical roles in regulating many nuclear processes by altering chromatin structure. One of the key H2A variants, H2A.X, marks DNA damage, facilitating the recruitment of DNA repair proteins to restore genomic integrity. Another variant, H2A.Z, plays an important role in both gene activation and repression. A high level of H2A.Z expression is detected in many cancers and is significantly associated with cellular proliferation and genomic instability.[11] Histone variant macroH2A1 is important in the pathogenesis of many types of cancers, for instance in hepatocellular carcinoma.[29] Other mechanisms include a decrease in H4K16ac may be caused by either a decrease in activity of a histone acetyltransferases (HATs) or an increase in deacetylation by SIRT1.[10] Likewise, an inactivating frameshift mutation in HDAC2, a histone deacetylase that acts on many histone-tail lysines, has been associated with cancers showing altered histone acetylation patterns.[30] These findings indicate a promising mechanism for altering epigenetic profiles through enzymatic inhibition or enhancement. A new emerging field that captures toxicological epigenetic changes as a result of the exposure to different compounds (drugs, food, and environment) is toxicoepigenetics. In this field, there is growing interest in mapping changes in histone modifications and their possible consequences.[31]

DNA damage, caused by UV light, ionizing radiation, environmental toxins, and metabolic chemicals, can also lead to genomic instability and cancer. The DNA damage response to double strand DNA breaks (DSB) is mediated in part by histone modifications. At a DSB, MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 (MRN) protein complex recruits ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) kinase which phosphorylates Serine 129 of Histone 2A. MDC1, mediator of DNA damage checkpoint 1, binds to the phosphopeptide, and phosphorylation of H2AX may spread by a positive feedback loop of MRN-ATM recruitment and phosphorylation. TIP60 acetylates the γH2AX, which is then polyubiquitylated. RAP80, a subunit of the DNA repair breast cancer type 1 susceptibility protein complex (BRCA1-A), binds ubiquitin attached to histones. BRCA1-A activity arrests the cell cycle at the G2/M checkpoint, allowing time for DNA repair, or apoptosis may be initiated.[32]

MicroRNA gene silencing

[edit]In mammals, microRNAs (miRNAs) regulate about 60% of the transcriptional activity of protein-encoding genes.[33] Some miRNAs also undergo methylation-associated silencing in cancer cells.[34][35] Let-7 and miR15/16 play important roles in down-regulating RAS and BCL2 oncogenes, and their silencing occurs in cancer cells.[18] Decreased expression of miR-125b1, a miRNA that functions as a tumor suppressor, was observed in prostate, ovarian, breast and glial cell cancers. In vitro experiments have shown that miR-125b1 targets two genes, HER2/neu and ESR1, that are linked to breast cancer. DNA methylation, specifically hypermethylation, is one of the main ways that the miR-125b1 is epigenetically silenced. In patients with breast cancer, hypermethylation of CpG islands located proximal to the transcription start site was observed. Loss of CTCF binding and an increase in repressive histone marks, H3K9me3 and H3K27me3, correlates with DNA methylation and miR-125b1 silencing. Mechanistically, CTCF may function as a boundary element to stop the spread of DNA methylation. Results from experiments conducted by Soto-Reyes et al.[36] indicate a negative effect of methylation on the function and expression of miR-125b1. Therefore, they concluded that DNA methylation has a part in silencing the gene. Furthermore, some miRNA's are epigenetically silenced early on in breast cancer, and therefore these miRNA's could potentially be useful as tumor markers.[36] The epigenetic silencing of miRNA genes by aberrant DNA methylation is a frequent event in cancer cells; almost one third of miRNA promoters active in normal mammary cells were found hypermethylated in breast cancer cells - that is a several fold greater proportion than is usually observed for protein coding genes.[37]

Metabolic recoding of epigenetics in cancer

[edit]Dysregulation of metabolism allows tumor cells to generate needed building blocks as well as to modulate epigenetic marks to support cancer initiation and progression. Cancer-induced metabolic changes alter the epigenetic landscape, especially modifications on histones and DNA, thereby promoting malignant transformation, adaptation to inadequate nutrition, and metastasis. In order to satisfy the biosynthetic demands of cancer cells, metabolic pathways are altered by manipulating oncogenes and tumor suppressive genes concurrently.[38] The accumulation of certain metabolites in cancer can target epigenetic enzymes to globally alter the epigenetic landscape. Cancer-related metabolic changes lead to locus-specific recoding of epigenetic marks. Cancer epigenetics can be precisely reprogramed by cellular metabolism through 1) dose-responsive modulation of cancer epigenetics by metabolites; 2) sequence-specific recruitment of metabolic enzymes; and 3) targeting of epigenetic enzymes by nutritional signals.[38] In addition to modulating metabolic programming on a molecular level, there are microenvironmental factors that can influence and effect metabolic recoding. These influences include nutritional, inflammatory, and the immune response of malignant tissues.

MicroRNA and DNA repair

[edit]DNA damage appears to be the primary underlying cause of cancer.[39][40] If DNA repair is deficient, DNA damage tends to accumulate. Such excess DNA damage can increase mutational errors during DNA replication due to error-prone translesion synthesis. Excess DNA damage can also increase epigenetic alterations due to errors during DNA repair.[41][42] Such mutations and epigenetic alterations can give rise to cancer (see malignant neoplasms).

Germ line mutations in DNA repair genes cause only 2–5% of colon cancer cases.[43] However, altered expression of microRNAs, causing DNA repair deficiencies, are frequently associated with cancers and may be an important causal factor for these cancers.

Over-expression of certain miRNAs may directly reduce expression of specific DNA repair proteins. Wan et al.[44] referred to 6 DNA repair genes that are directly targeted by the miRNAs indicated in parentheses: ATM (miR-421), RAD52 (miR-210, miR-373), RAD23B (miR-373), MSH2 (miR-21), BRCA1 (miR-182) and P53 (miR-504, miR-125b). More recently, Tessitore et al.[45] listed further DNA repair genes that are directly targeted by additional miRNAs, including ATM (miR-18a, miR-101), DNA-PK (miR-101), ATR (miR-185), Wip1 (miR-16), MLH1, MSH2 and MSH6 (miR-155), ERCC3 and ERCC4 (miR-192) and UNG2 (mir-16, miR-34c and miR-199a). Of these miRNAs, miR-16, miR-18a, miR-21, miR-34c, miR-125b, miR-101, miR-155, miR-182, miR-185 and miR-192 are among those identified by Schnekenburger and Diederich[46] as over-expressed in colon cancer through epigenetic hypomethylation. Over expression of any one of these miRNAs can cause reduced expression of its target DNA repair gene.

Up to 15% of the MLH1-deficiencies in sporadic colon cancers appeared to be due to over-expression of the microRNA miR-155, which represses MLH1 expression.[47] However, the majority of 68 sporadic colon cancers with reduced expression of the DNA mismatch repair protein MLH1 were found to be deficient due to epigenetic methylation of the CpG island of the MLH1 gene.[48]

In 28% of glioblastomas, the MGMT DNA repair protein is deficient but the MGMT promoter is not methylated.[49] In the glioblastomas without methylated MGMT promoters, the level of microRNA miR-181d is inversely correlated with protein expression of MGMT and the direct target of miR-181d is the MGMT mRNA 3'UTR (the three prime untranslated region of MGMT mRNA).[49] Thus, in 28% of glioblastomas, increased expression of miR-181d and reduced expression of DNA repair enzyme MGMT may be a causal factor. In 29–66%[49][50] of glioblastomas, DNA repair is deficient due to epigenetic methylation of the MGMT gene, which reduces protein expression of MGMT.

High mobility group A (HMGA) proteins, characterized by an AT-hook, are small, nonhistone, chromatin-associated proteins that can modulate transcription. MicroRNAs control the expression of HMGA proteins, and these proteins (HMGA1 and HMGA2) are architectural chromatin transcription-controlling elements. Palmieri et al.[51] showed that, in normal tissues, HGMA1 and HMGA2 genes are targeted (and thus strongly reduced in expression) by miR-15, miR-16, miR-26a, miR-196a2 and Let-7a.

HMGA expression is almost undetectable in differentiated adult tissues but is elevated in many cancers. HGMA proteins are polypeptides of ~100 amino acid residues characterized by a modular sequence organization. These proteins have three highly positively charged regions, termed AT hooks, that bind the minor groove of AT-rich DNA stretches in specific regions of DNA. Human neoplasias, including thyroid, prostatic, cervical, colorectal, pancreatic and ovarian carcinoma, show a strong increase of HMGA1a and HMGA1b proteins.[52] Transgenic mice with HMGA1 targeted to lymphoid cells develop aggressive lymphoma, showing that high HMGA1 expression is not only associated with cancers, but that the HMGA1 gene can act as an oncogene to cause cancer.[53] Baldassarre et al.,[54] showed that HMGA1 protein binds to the promoter region of DNA repair gene BRCA1 and inhibits BRCA1 promoter activity. They also showed that while only 11% of breast tumors had hypermethylation of the BRCA1 gene, 82% of aggressive breast cancers have low BRCA1 protein expression, and most of these reductions were due to chromatin remodeling by high levels of HMGA1 protein.

HMGA2 protein specifically targets the promoter of ERCC1, thus reducing expression of this DNA repair gene.[55] ERCC1 protein expression was deficient in 100% of 47 evaluated colon cancers (though the extent to which HGMA2 was involved is unknown).[56]

Palmieri et al.[51] showed that each of the miRNAs that target HMGA genes are drastically reduced in almost all human pituitary adenomas studied, when compared with the normal pituitary gland. Consistent with the down-regulation of these HMGA-targeting miRNAs, an increase in the HMGA1 and HMGA2-specific mRNAs was observed. Three of these microRNAs (miR-16, miR-196a and Let-7a)[46][57] have methylated promoters and therefore low expression in colon cancer. For two of these, miR-15 and miR-16, the coding regions are epigenetically silenced in cancer due to histone deacetylase activity.[58] When these microRNAs are expressed at a low level, then HMGA1 and HMGA2 proteins are expressed at a high level. HMGA1 and HMGA2 target (reduce expression of) BRCA1 and ERCC1 DNA repair genes. Thus DNA repair can be reduced, likely contributing to cancer progression.[40]

DNA repair pathways

[edit]

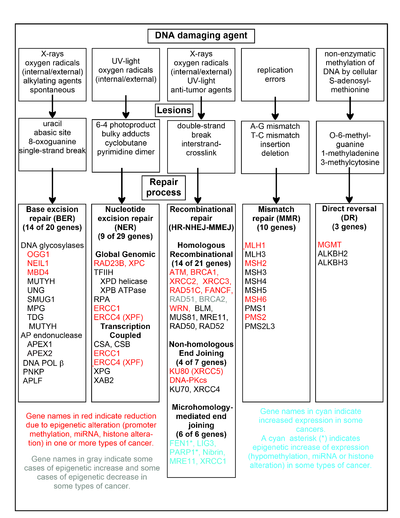

The chart in this section shows some frequent DNA damaging agents, examples of DNA lesions they cause, and the pathways that deal with these DNA damages. At least 169 enzymes are either directly employed in DNA repair or influence DNA repair processes.[59] Of these, 83 are directly employed in repairing the 5 types of DNA damages illustrated in the chart.

Some of the more well studied genes central to these repair processes are shown in the chart. The gene designations shown in red, gray or cyan indicate genes frequently epigenetically altered in various types of cancers. Wikipedia articles on each of the genes highlighted by red, gray or cyan describe the epigenetic alteration(s) and the cancer(s) in which these epimutations are found. Two broad experimental survey articles[60][61] also document most of these epigenetic DNA repair deficiencies in cancers.

Red-highlighted genes are frequently reduced or silenced by epigenetic mechanisms in various cancers. When these genes have low or absent expression, DNA damages can accumulate. Replication errors past these damages (see translesion synthesis) can lead to increased mutations and, ultimately, cancer. Epigenetic repression of DNA repair genes in accurate DNA repair pathways appear to be central to carcinogenesis.

The two gray-highlighted genes RAD51 and BRCA2, are required for homologous recombinational repair. They are sometimes epigenetically over-expressed and sometimes under-expressed in certain cancers. As indicated in the Wikipedia articles on RAD51 and BRCA2, such cancers ordinarily have epigenetic deficiencies in other DNA repair genes. These repair deficiencies would likely cause increased unrepaired DNA damages. The over-expression of RAD51 and BRCA2 seen in these cancers may reflect selective pressures for compensatory RAD51 or BRCA2 over-expression and increased homologous recombinational repair to at least partially deal with such excess DNA damages. In those cases where RAD51 or BRCA2 are under-expressed, this would itself lead to increased unrepaired DNA damages. Replication errors past these damages (see translesion synthesis) could cause increased mutations and cancer, so that under-expression of RAD51 or BRCA2 would be carcinogenic in itself.

Cyan-highlighted genes are in the microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ) pathway and are up-regulated in cancer. MMEJ is an additional error-prone inaccurate repair pathway for double-strand breaks. In MMEJ repair of a double-strand break, an homology of 5-25 complementary base pairs between both paired strands is sufficient to align the strands, but mismatched ends (flaps) are usually present. MMEJ removes the extra nucleotides (flaps) where strands are joined, and then ligates the strands to create an intact DNA double helix. MMEJ almost always involves at least a small deletion, so that it is a mutagenic pathway.[62] FEN1, the flap endonuclease in MMEJ, is epigenetically increased by promoter hypomethylation and is over-expressed in the majority of cancers of the breast,[63] prostate,[64] stomach,[65][66] neuroblastomas,[67] pancreas,[68] and lung.[69] PARP1 is also over-expressed when its promoter region ETS site is epigenetically hypomethylated, and this contributes to progression to endometrial cancer,[70] BRCA-mutated ovarian cancer,[71] and BRCA-mutated serous ovarian cancer.[72] Other genes in the MMEJ pathway are also over-expressed in a number of cancers (see MMEJ for summary), and are also shown in blue.

Frequencies of epimutations in DNA repair genes

[edit]Deficiencies in DNA repair proteins that function in accurate DNA repair pathways increase the risk of mutation. Mutation rates are strongly increased in cells with mutations in DNA mismatch repair[73][74] or in homologous recombinational repair (HRR).[75] Individuals with inherited mutations in any of 34 DNA repair genes are at increased risk of cancer (see DNA repair defects and increased cancer risk).

In sporadic cancers, a deficiency in DNA repair is occasionally found to be due to a mutation in a DNA repair gene, but much more frequently reduced or absent expression of DNA repair genes is due to epigenetic alterations that reduce or silence gene expression. For example, for 113 colorectal cancers examined in sequence, only four had a missense mutation in the DNA repair gene MGMT, while the majority had reduced MGMT expression due to methylation of the MGMT promoter region (an epigenetic alteration).[76] Similarly, out of 119 cases of mismatch repair-deficient colorectal cancers that lacked DNA repair gene PMS2 expression, PMS2 protein was deficient in 6 due to mutations in the PMS2 gene, while in 103 cases PMS2 expression was deficient because its pairing partner MLH1 was repressed due to promoter methylation (PMS2 protein is unstable in the absence of MLH1).[48] In the other 10 cases, loss of PMS2 expression was likely due to epigenetic overexpression of the microRNA, miR-155, which down-regulates MLH1.[47]

Epigenetic defects in DNA repair genes are frequent in cancers. In the table, multiple cancers were evaluated for reduced or absent expression of the DNA repair gene of interest, and the frequency shown is the frequency with which the cancers had an epigenetic deficiency of gene expression. Such epigenetic deficiencies likely arise early in carcinogenesis, since they are also frequently found (though at somewhat lower frequency) in the field defect surrounding the cancer from which the cancer likely arose (see Table).

| Cancer | Gene | Frequency in Cancer | Frequency in Field Defect | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal | MGMT | 46% | 34% | [77] |

| Colorectal | MGMT | 47% | 11% | [78] |

| Colorectal | MGMT | 70% | 60% | [79] |

| Colorectal | MSH2 | 13% | 5% | [78] |

| Colorectal | ERCC1 | 100% | 40% | [56] |

| Colorectal | PMS2 | 88% | 50% | [56] |

| Colorectal | XPF | 55% | 40% | [56] |

| Head and Neck | MGMT | 54% | 38% | [80] |

| Head and Neck | MLH1 | 33% | 25% | [81] |

| Head and Neck | MLH1 | 31% | 20% | [82] |

| Stomach | MGMT | 88% | 78% | [83] |

| Stomach | MLH1 | 73% | 20% | [84] |

| Stomach | ERCC1 | 95-100% | 14-65% | [85] |

| Stomach | PMS2 | 95-100% | 14-60% | [85] |

| Esophagus | MLH1 | 77%–100% | 23%–79% | [86] |

It appears that cancers may frequently be initiated by an epigenetic reduction in expression of one or more DNA repair enzymes. Reduced DNA repair likely allows accumulation of DNA damages. Error prone translesion synthesis past some of these DNA damages may give rise to a mutation with a selective advantage. A clonal patch with a selective advantage may grow and out-compete neighboring cells, forming a field defect. While there is no obvious selective advantage for a cell to have reduced DNA repair, the epimutation of the DNA repair gene may be carried along as a passenger when the cells with the selectively advantageous mutation are replicated. In the cells carrying both the epimutation of the DNA repair gene and the mutation with the selective advantage, further DNA damages will accumulate, and these could, in turn, give rise to further mutations with still greater selective advantages. Epigenetic defects in DNA repair may thus contribute to the characteristic high frequency of mutations in the genomes of cancers, and cause their carcinogenic progression.

Cancers have high levels of genome instability, associated with a high frequency of mutations. A high frequency of genomic mutations increases the likelihood of particular mutations occurring that activate oncogenes and inactivate tumor suppressor genes, leading to carcinogenesis. On the basis of whole genome sequencing, cancers are found to have thousands to hundreds of thousands of mutations in their whole genomes.[87] (Also see Mutation frequencies in cancers.) By comparison, the mutation frequency in the whole genome between generations for humans (parent to child) is about 70 new mutations per generation.[88][89] In the protein coding regions of the genome, there are only about 0.35 mutations between parent/child generations (less than one mutated protein per generation).[90] Whole genome sequencing in blood cells for a pair of identical twin 100-year-old centenarians only found 8 somatic differences, though somatic variation occurring in less than 20% of blood cells would be undetected.[91]

While DNA damages may give rise to mutations through error prone translesion synthesis, DNA damages can also give rise to epigenetic alterations during faulty DNA repair processes.[41][42][92][93] The DNA damages that accumulate due to epigenetic DNA repair defects can be a source of the increased epigenetic alterations found in many genes in cancers. In an early study, looking at a limited set of transcriptional promoters, Fernandez et al.[94] examined the DNA methylation profiles of 855 primary tumors. Comparing each tumor type with its corresponding normal tissue, 729 CpG island sites (55% of the 1322 CpG sites evaluated) showed differential DNA methylation. Of these sites, 496 were hypermethylated (repressed) and 233 were hypomethylated (activated). Thus, there is a high level of epigenetic promoter methylation alterations in tumors. Some of these epigenetic alterations may contribute to cancer progression.

Epigenetic carcinogens

[edit]A variety of compounds are considered as epigenetic carcinogens—they result in an increased incidence of tumors, but they do not show mutagen activity (toxic compounds or pathogens that cause tumors incident to increased regeneration should also be excluded). Examples include diethylstilbestrol, arsenite, hexachlorobenzene, and nickel compounds.

Many teratogens exert specific effects on the fetus by epigenetic mechanisms.[95][96] While epigenetic effects may preserve the effect of a teratogen such as diethylstilbestrol throughout the life of an affected child, the possibility of birth defects resulting from exposure of fathers or in second and succeeding generations of offspring has generally been rejected on theoretical grounds and for lack of evidence.[97] However, a range of male-mediated abnormalities have been demonstrated, and more are likely to exist.[98] FDA label information for Vidaza, a formulation of 5-azacitidine (an unmethylatable analog of cytidine that causes hypomethylation when incorporated into DNA) states that "men should be advised not to father a child" while using the drug, citing evidence in treated male mice of reduced fertility, increased embryo loss, and abnormal embryo development.[99] In rats, endocrine differences were observed in offspring of males exposed to morphine.[100] In mice, second generation effects of diethylstilbesterol have been described occurring by epigenetic mechanisms.[101]

Cancer subtypes

[edit]Skin cancer

[edit]Melanoma is a deadly skin cancer that originates from melanocytes. Several epigenetic alterations are known to play a role in the transition of melanocytes to melanoma cells. This includes DNA methylation that can be inherited without making changes to the DNA sequence, as well as silencing the tumor suppressor genes in the epidermis that have been exposed to UV radiation for periods of time.[102] The silencing of tumor suppressor genes leads to photocarcinogenesis which is associated to epigenetic alterations in DNA methylation, DNA methyltransferases, and histone acetylation.[102] These alterations are the consequence of deregulation of their corresponding enzymes. Several histone methyltransferases and demethylases are among these enzymes.[103]

Prostate cancer

[edit]Prostate cancer kills around 35,000 men yearly, and about 220,000 men are diagnosed with prostate cancer per year, in North America alone.[104] Prostate cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-caused fatalities in men, and within a man's lifetime, one in six men will have the disease.[104] Alterations in histone acetylation and DNA methylation occur in various genes influencing prostate cancer, and have been seen in genes involved in hormonal response.[105] More than 90% of prostate cancers show gene silencing by CpG island hypermethylation of the GSTP1 gene promoter, which protects prostate cells from genomic damage that is caused by different oxidants or carcinogens.[106] Real-time methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) suggests that many other genes are also hypermethylated.[106] Gene expression in the prostate may be modulated by nutrition and lifestyle changes.[107]

Cervical cancer

[edit]The second most common malignant tumor in women is invasive cervical cancer (ICC) and more than 50% of all invasive cervical cancer (ICC) is caused by oncongenic human papillomavirus 16 (HPV16).[108] Furthermore, cervix intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) is primarily caused by oncogenic HPV16.[108] As in many cases, the causative factor for cancer does not always take a direct route from infection to the development of cancer. Genomic methylation patterns have been associated with invasive cervical cancer. Within the HPV16L1 region, 14 tested CpG sites have significantly higher methylation in CIN3+ than in HPV16 genomes of women without CIN3.[108] Only 2/16 CpG sites tested in HPV16 upstream regulatory region were found to have association with increased methylation in CIN3+.[108] This suggests that the direct route from infection to cancer is sometimes detoured to a precancerous state in cervix intraepithelial neoplasia. Additionally, increased CpG site methylation was found in low levels in most of the five host nuclear genes studied, including 5/5 TERT, 1/4 DAPK1, 2/5 RARB, MAL, and CADM1.[108] Furthermore, 1/3 of CpG sites in mitochondrial DNA were associated with increased methylation in CIN3+.[108] Thus, a correlation exists between CIN3+ and increased methylation of CpG sites in the HPV16 L1 open reading frame.[108] This could be a potential biomarker for future screens of cancerous and precancerous cervical disease.[108]

Leukemia

[edit]Recent studies have shown that the mixed-lineage leukemia (MLL) gene causes leukemia by rearranging and fusing with other genes in different chromosomes, which is a process under epigenetic control.[109] Mutations in MLL block the correct regulatory regions in leukemia associated translocations or insertions causing malignant transformation controlled by HOX genes.[110] This is what leads to the increase in white blood cells. Leukemia related genes are managed by the same pathways that control epigenetics, signaling transduction, transcriptional regulation, and energy metabolism. It was indicated that infections, electromagnetic fields and increased birth weight can contribute to being the causes of leukemia.[111]

Sarcoma

[edit]There are about 15,000 new cases of sarcoma in the US each year, and about 6,200 people were projected to die of sarcoma in the US in 2014.[112] Sarcomas comprise a large number of rare, histogenetically heterogeneous mesenchymal tumors that, for example, include chondrosarcoma, Ewing's sarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, liposarcoma, osteosarcoma, synovial sarcoma, and (alveolar and embryonal) rhabdomyosarcoma. Several oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes are epigenetically altered in sarcomas. These include APC, CDKN1A, CDKN2A, CDKN2B, Ezrin, FGFR1, GADD45A, MGMT, STK3, STK4, PTEN, RASSF1A, WIF1, as well as several miRNAs.[113] Expression of epigenetic modifiers such as that of the BMI1 component of the PRC1 complex is deregulated in chondrosarcoma, Ewing's sarcoma, and osteosarcoma, and expression of the EZH2 component of the PRC2 complex is altered in Ewing's sarcoma and rhabdomyosarcoma. Similarly, expression of another epigenetic modifier, the LSD1 histone demethylase, is increased in chondrosarcoma, Ewing's sarcoma, osteosarcoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma. Drug targeting and inhibition of EZH2 in Ewing's sarcoma,[114] or of LSD1 in several sarcomas,[115] inhibits tumor cell growth in these sarcomas.

Lung Cancer

[edit]Lung cancer is the second most common type of cancer and leading cause of death in men and women in the United States, it is estimated that there is about 216,000 new cases and 160,000 deaths due to lung cancer.[116]

Initiation and progression of lung carcinoma is the result of the interaction between genetic, epigenetic and environmental factors. Most cases of lung cancer are because of genetic mutations in EGFR, KRAS, STK11 (also known as LKB1), TP53 (also known as p53), and CDKN2A (also known as p16 or INK4a)[117][118][119] with the most common type of lung cancer being an inactivation at p16. p16 is a tumor suppressor protein that occurs in mostly in humans the functional significance of the mutations was tested on many other species including mice, cats, dogs, monkeys and cows the identification of these multiple nonoverlapping clones was not entirely surprising since the reduced stringency hybridization of a zoo blot with the same probe also revealed 10-15 positive EcoRI fragments in all species tested.[120]

Identification methods

[edit]Previously, epigenetic profiles were limited to individual genes under scrutiny by a particular research team. Recently, however, scientists have been moving toward a more genomic approach to determine an entire genomic profile for cancerous versus healthy cells.[10]

Popular approaches for measuring CpG methylation in cells include:

- Bisulfite sequencing

- Combined bisulfite restriction analysis (COBRA)

- Methylation-specific PCR

- MethyLight

- Pyrosequencing

- Restriction landmark genomic scanning

- Arbitrary primed PCR

- HELP assay (HpaII tiny fragment enrichment by ligation-mediated PCR)

- Chromatin immunoprecipitation ChIP-Chip using antibodies specific for methyl-CpG binding domain proteins

- Methylated DNA immunoprecipitation Methyl-DIP

- Gene-expression profiles via DNA microarray : comparing mRNA levels from cancer cell lines before and after treatment with a demethylating agent

Since bisulfite sequencing is considered the gold standard for measuring CpG methylation, when one of the other methods is used, results are usually confirmed using bisulfite sequencing[1]. Popular approaches for determining histone modification profiles in cancerous versus healthy cells include:[10]

- Mass spectrometry

- Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay

Diagnosis and prognosis

[edit]Researchers are hoping to identify specific epigenetic profiles of various types and subtypes of cancer with the goal of using these profiles as tools to diagnose individuals more specifically and accurately.[10] Since epigenetic profiles change, scientists would like to use the different epigenomic profiles to determine the stage of development or level of aggressiveness of a particular cancer in patients. For example, hypermethylation of the genes coding for Death-Associated Protein Kinase (DAPK), p16, and Epithelial Membrane Protein 3 (EMP3) have been linked to more aggressive forms of lung, colorectal, and brain cancers.[17] This type of knowledge can affect the way that doctors will diagnose and choose to treat their patients.

Another factor that will influence the treatment of patients is knowing how well they will respond to certain treatments. Personalized epigenomic profiles of cancerous cells can provide insight into this field. For example, MGMT is an enzyme that reverses the addition of alkyl groups to the nucleotide guanine.[121] Alkylating guanine, however, is the mechanism by which several chemotherapeutic drugs act in order to disrupt DNA and cause cell death.[122][123][124][125] Therefore, if the gene encoding MGMT in cancer cells is hypermethylated and in effect silenced or repressed, the chemotherapeutic drugs that act by methylating guanine will be more effective than in cancer cells that have a functional MGMT enzyme.

Epigenetic biomarkers can also be utilized as tools for molecular prognosis. In primary tumor and mediastinal lymph node biopsy samples, hypermethylation of both CDKN2A and CDH13 serves as the marker for increased risk of faster cancer relapse and higher death rate of patients.[126]

Treatment

[edit]

Epigenetic control of the proto-onco regions and the tumor suppressor sequences by conformational changes in histones plays a role in the formation and progression of cancer.[127] Pharmaceuticals that reverse epigenetic changes might have a role in a variety of cancers.[105][127][128]

Recently, it is evidently known that associations between specific cancer histotypes and epigenetic changes can facilitate the development of novel epi-drugs.[129] Drug development has focused mainly on modifying DNA methyltransferase, histone acetyltransferase (HAT) and histone deacetylase (HDAC).[130]

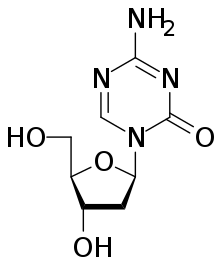

Drugs that specifically target the inverted methylation pattern of cancerous cells include the DNA methyltransferase inhibitors azacitidine[131][132] and decitabine.[133][134] These hypomethylating agents are used to treat myelodysplastic syndrome,[135] a blood cancer produced by abnormal bone marrow stem cells.[12] These agents inhibit all three types of active DNA methyltransferases, and had been thought to be highly toxic, but proved to be effective when used in low dosage, reducing progression of myelodysplastic syndrome to leukemia.[136]

Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors show efficacy in treatment of T cell lymphoma. two HDAC inhibitors, vorinostat and romidepsin, have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration.[137][138] However, since these HDAC inhibitors alter the acetylation state of many proteins in addition to the histone of interest, knowledge of the underlying mechanism at the molecular level of patient response is required to enhance the efficiency of using such inhibitors as treatment.[18] Treatment with HDAC inhibitors has been found to promote gene reactivation after DNA methyl-transferases inhibitors have repressed transcription.[139] Panobinostat is approved for certain situations in myeloma.[140]

Other pharmaceutical targets in research are histone lysine methyltransferases (KMT) and protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMT).[141] Preclinical study has suggested that lunasin may have potentially beneficial epigenetic effects.[142]

Epigenetic Therapy

[edit]Epigenetic therapy of cancer has shown to be a promising and possible treatment of cancerous cells. Epigenetic inactivation is an ideal target for cancerous cells because it targets genes imperative for controlling cell growth, specifically cancer cell growth. It is crucial for these genes to be reactivated in order to suppress tumor growth and sensitize the cells to cancer curing therapies.[143] Typical chemotherapy aims to kill and eliminate cancer cells in the body. Cancer initiated by genetic alterations of cells are typically permanent and nearly impossible to reverse, this differs from epigenetic cancer because the cancer causing epigenetic aberrations have the capability of being reversed, and the cells being returned to normal function. The ability for epigenetic mechanisms to be reversed is attributed to the fact that the coding of the genes being silenced through histone and DNA modification is not being altered.[144]

There are two primary types of epigenetic alterations in cancer cells, these are known as DNA methylation and Histone modification. It is the goal of epigenetic therapies to inhibit these alterations. DNA Methyltransferases (DNMTs) and Histone Deacetylases (HDAC) are the primary catalyzes of the epigenetic modifications of cancer cells.[145] The goal for epigenetic therapies is to repress this methylation and reverse these modifications in order to create a new epigenome where cancer cells no longer thrive and tumor suppression is the new function. Synthetic drugs are used as tools in epigenetic therapies due to their ability to inhibit enzymes causing histone modifications and DNA methylations. Combination therapy is one method of epigenetic therapy which involves the use of more than one synthetic drug, these drugs include a low dose DNMT inhibitor as well as an HDAC inhibitor. Together, these drugs are able to target the linkage between DNA methylation and Histone modification.[146]

The goal of epigenetic therapies for cancer in relation to DNA methylation is to both decrease the methylation of DNA and in turn decrease the silencing of genes related to tumor suppression.[147] The term associated with decreasing the methylation of DNA will be known as hypomethylation. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has currently approved one hypomethylating agent which, through the conduction of clinical trials, has shown promising results when utilized to treat patients with Myelodysplastic Syndrome (MDS).[148] This hypomethylating agent is known as the doozy analogue of 5-azacytidine and works to promote hypomethylation by targeting all DNA methyltransferases for degradation.[147]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Sharma S, Kelly TK, Jones PA (January 2010). "Epigenetics in cancer". Carcinogenesis. 31 (1): 27–36. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgp220. PMC 2802667. PMID 19752007.

- ^ Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu VE, Zhou S, Diaz LA, Kinzler KW (March 2013). "Cancer genome landscapes". Science. 339 (6127): 1546–1558. Bibcode:2013Sci...339.1546V. doi:10.1126/science.1235122. PMC 3749880. PMID 23539594.

- ^ Illingworth RS, Gruenewald-Schneider U, Webb S, Kerr AR, James KD, Turner DJ, et al. (September 2010). "Orphan CpG islands identify numerous conserved promoters in the mammalian genome". PLOS Genetics. 6 (9): e1001134. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001134. PMC 2944787. PMID 20885785.

- ^ Wei J, Li G, Dang S, Zhou Y, Zeng K, Liu M (2016). "Discovery and Validation of Hypermethylated Markers for Colorectal Cancer". Disease Markers. 2016: 2192853. doi:10.1155/2016/2192853. PMC 4963574. PMID 27493446.

- ^ Beggs AD, Jones A, El-Bahrawy M, El-Bahwary M, Abulafi M, Hodgson SV, Tomlinson IP (April 2013). "Whole-genome methylation analysis of benign and malignant colorectal tumours". The Journal of Pathology. 229 (5): 697–704. doi:10.1002/path.4132. PMC 3619233. PMID 23096130.

- ^ Novak K (December 2004). "Epigenetics changes in cancer cells". MedGenMed. 6 (4): 17. PMC 1480584. PMID 15775844.

- ^ Banno K, Kisu I, Yanokura M, Tsuji K, Masuda K, Ueki A, et al. (September 2012). "Epimutation and cancer: a new carcinogenic mechanism of Lynch syndrome (Review)". International Journal of Oncology. 41 (3): 793–797. doi:10.3892/ijo.2012.1528. PMC 3582986. PMID 22735547.

- ^ Bird A (January 2002). "DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory". Genes & Development. 16 (1): 6–21. doi:10.1101/gad.947102. PMID 11782440.

- ^ Herman JG, Graff JR, Myöhänen S, Nelkin BD, Baylin SB (September 1996). "Methylation-specific PCR: a novel PCR assay for methylation status of CpG islands". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 93 (18): 9821–9826. Bibcode:1996PNAS...93.9821H. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.18.9821. PMC 38513. PMID 8790415.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Esteller M (April 2007). "Cancer epigenomics: DNA methylomes and histone-modification maps". Nature Reviews. Genetics. 8 (4): 286–298. doi:10.1038/nrg2005. PMID 17339880. S2CID 4801662.

- ^ a b Wong NC, Craig JM (2011). Epigenetics: A Reference Manual. Norfolk, England: Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-88-2.

- ^ a b c Jones PA, Baylin SB (June 2002). "The fundamental role of epigenetic events in cancer". Nature Reviews. Genetics. 3 (6): 415–428. doi:10.1038/nrg816. PMID 12042769. S2CID 2122000.

- ^ De Carvalho DD, Sharma S, You JS, Su SF, Taberlay PC, Kelly TK, et al. (May 2012). "DNA methylation screening identifies driver epigenetic events of cancer cell survival". Cancer Cell. 21 (5): 655–667. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2012.03.045. PMC 3395886. PMID 22624715.

- ^ a b c Herman JG, Baylin SB (November 2003). "Gene silencing in cancer in association with promoter hypermethylation". The New England Journal of Medicine. 349 (21): 2042–2054. doi:10.1056/NEJMra023075. PMID 14627790.

- ^ a b c Feinberg AP, Tycko B (February 2004). "The history of cancer epigenetics". Nature Reviews. Cancer. 4 (2): 143–153. doi:10.1038/nrc1279. PMID 14732866. S2CID 31655008.

- ^ a b c Egger G, Liang G, Aparicio A, Jones PA (May 2004). "Epigenetics in human disease and prospects for epigenetic therapy". Nature. 429 (6990): 457–463. Bibcode:2004Natur.429..457E. doi:10.1038/nature02625. PMID 15164071. S2CID 4424126.

- ^ a b c d Esteller M (2005). "Aberrant DNA methylation as a cancer-inducing mechanism". Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 45: 629–656. doi:10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095832. PMID 15822191.

- ^ a b c Baylin SB, Jones PA (September 2011). "A decade of exploring the cancer epigenome - biological and translational implications". Nature Reviews. Cancer. 11 (10): 726–734. doi:10.1038/nrc3130. PMC 3307543. PMID 21941284.

- ^ Ellermeier C, Higuchi EC, Phadnis N, Holm L, Geelhood JL, Thon G, Smith GR (May 2010). "RNAi and heterochromatin repress centromeric meiotic recombination". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (19): 8701–8705. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.8701E. doi:10.1073/pnas.0914160107. PMC 2889303. PMID 20421495.

- ^ Esteller M (April 2007). "Cancer epigenomics: DNA methylomes and histone-modification maps". Nature Reviews. Genetics. 8 (4): 286–298. doi:10.1038/nrg2005. PMID 17339880. S2CID 4801662.

- ^ Timp W, Feinberg AP (July 2013). "Cancer as a dysregulated epigenome allowing cellular growth advantage at the expense of the host". Nature Reviews. Cancer. 13 (7): 497–510. doi:10.1038/nrc3486. PMC 4636434. PMID 23760024.

- ^ a b Fraga MF, Ballestar E, Villar-Garea A, Boix-Chornet M, Espada J, Schotta G, et al. (April 2005). "Loss of acetylation at Lys16 and trimethylation at Lys20 of histone H4 is a common hallmark of human cancer". Nature Genetics. 37 (4): 391–400. doi:10.1038/ng1531. PMID 15765097. S2CID 27245550.

- ^ Aprelikova O, Chen K, El Touny LH, Brignatz-Guittard C, Han J, Qiu T, et al. (Apr 2016). "The epigenetic modifier JMJD6 is amplified in mammary tumors and cooperates with c-Myc to enhance cellular transformation, tumor progression, and metastasis". Clinical Epigenetics. 8 (38): 38. doi:10.1186/s13148-016-0205-6. PMC 4831179. PMID 27081402.

- ^ Dang W, Steffen KK, Perry R, Dorsey JA, Johnson FB, Shilatifard A, et al. (June 2009). "Histone H4 lysine 16 acetylation regulates cellular lifespan". Nature. 459 (7248): 802–807. Bibcode:2009Natur.459..802D. doi:10.1038/nature08085. PMC 2702157. PMID 19516333.

- ^ Viré E, Brenner C, Deplus R, Blanchon L, Fraga M, Didelot C, et al. (February 2006). "The Polycomb group protein EZH2 directly controls DNA methylation". Nature. 439 (7078): 871–874. Bibcode:2006Natur.439..871V. doi:10.1038/nature04431. PMID 16357870. S2CID 4409726.

- ^ Richon VM, Sandhoff TW, Rifkind RA, Marks PA (August 2000). "Histone deacetylase inhibitor selectively induces p21WAF1 expression and gene-associated histone acetylation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (18): 10014–10019. Bibcode:2000PNAS...9710014R. doi:10.1073/pnas.180316197. JSTOR 123305. PMC 27656. PMID 10954755.

- ^ Maxmen A (August 2012). "Cancer research: Open ambition". Nature. 488 (7410): 148–150. Bibcode:2012Natur.488..148M. doi:10.1038/488148a. PMID 22874946.

- ^ a b Soto-Reyes E, Recillas-Targa F (April 2010). "Epigenetic regulation of the human p53 gene promoter by the CTCF transcription factor in transformed cell lines". Oncogene. 29 (15): 2217–2227. doi:10.1038/onc.2009.509. PMID 20101205. S2CID 23983571.

- ^ Rappa F, Greco A, Podrini C, Cappello F, Foti M, Bourgoin L, et al. (2013). Folli F (ed.). "Immunopositivity for histone macroH2A1 isoforms marks steatosis-associated hepatocellular carcinoma". PLOS ONE. 8 (1): e54458. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...854458R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0054458. PMC 3553099. PMID 23372727.

- ^ Ropero S, Fraga MF, Ballestar E, Hamelin R, Yamamoto H, Boix-Chornet M, et al. (May 2006). "A truncating mutation of HDAC2 in human cancers confers resistance to histone deacetylase inhibition". Nature Genetics. 38 (5): 566–569. doi:10.1038/ng1773. PMID 16642021. S2CID 9073684.

- ^ Verhelst, Sigrid; Van Puyvelde, Bart; Willems, Sander; Daled, Simon; Cornelis, Senne; Corveleyn, Laura; Willems, Ewoud; Deforce, Dieter; De Clerck, Laura; Dhaenens, Maarten (2022-01-24). "A large scale mass spectrometry-based histone screening for assessing epigenetic developmental toxicity". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 1256. Bibcode:2022NatSR..12.1256V. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-05268-x. hdl:1854/LU-8735551. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 8786925. PMID 35075221.

- ^ van Attikum H, Gasser SM (May 2009). "Crosstalk between histone modifications during the DNA damage response". Trends in Cell Biology. 19 (5): 207–217. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2009.03.001. PMID 19342239.

- ^ Friedman RC, Farh KK, Burge CB, Bartel DP (January 2009). "Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs". Genome Research. 19 (1): 92–105. doi:10.1101/gr.082701.108. PMC 2612969. PMID 18955434.

- ^ Saito Y, Liang G, Egger G, Friedman JM, Chuang JC, Coetzee GA, Jones PA (June 2006). "Specific activation of microRNA-127 with downregulation of the proto-oncogene BCL6 by chromatin-modifying drugs in human cancer cells". Cancer Cell. 9 (6): 435–443. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2006.04.020. PMID 16766263.

- ^ Lujambio A, Ropero S, Ballestar E, Fraga MF, Cerrato C, Setién F, et al. (February 2007). "Genetic unmasking of an epigenetically silenced microRNA in human cancer cells". Cancer Research. 67 (4): 1424–1429. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4218. PMID 17308079.

- ^ a b Soto-Reyes E, González-Barrios R, Cisneros-Soberanis F, Herrera-Goepfert R, Pérez V, Cantú D, et al. (January 2012). "Disruption of CTCF at the miR-125b1 locus in gynecological cancers". BMC Cancer. 12: 40. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-12-40. PMC 3297514. PMID 22277129.

- ^ Vrba L, Muñoz-Rodríguez JL, Stampfer MR, Futscher BW (2013). "miRNA gene promoters are frequent targets of aberrant DNA methylation in human breast cancer". PLOS ONE. 8 (1): e54398. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...854398V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0054398. PMC 3547033. PMID 23342147.

- ^ a b Wang YP, Lei QY (May 2018). "Metabolic recoding of epigenetics in cancer". Cancer Communications. 38 (1): 25. doi:10.1186/s40880-018-0302-3. PMC 5993135. PMID 29784032.

- ^ Kastan MB (April 2008). "DNA damage responses: mechanisms and roles in human disease: 2007 G.H.A. Clowes Memorial Award Lecture". Molecular Cancer Research. 6 (4): 517–524. doi:10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0020. PMID 18403632.

- ^ a b Bernstein C, Prasad AR, Nfonsam V, Bernstein H (2013). "Chapter 16: DNA Damage, DNA Repair and Cancer". In Chen C (ed.). New Research Directions in DNA Repair. BoD – Books on Demand. p. 413. ISBN 978-953-51-1114-6.

- ^ a b O'Hagan HM, Mohammad HP, Baylin SB (August 2008). "Double strand breaks can initiate gene silencing and SIRT1-dependent onset of DNA methylation in an exogenous promoter CpG island". PLOS Genetics. 4 (8): e1000155. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000155. PMC 2491723. PMID 18704159.

- ^ a b Cuozzo C, Porcellini A, Angrisano T, Morano A, Lee B, Di Pardo A, et al. (July 2007). "DNA damage, homology-directed repair, and DNA methylation". PLOS Genetics. 3 (7): e110. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030110. PMC 1913100. PMID 17616978.

- ^ Jasperson KW, Tuohy TM, Neklason DW, Burt RW (June 2010). "Hereditary and familial colon cancer". Gastroenterology. 138 (6): 2044–2058. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2010.01.054. PMC 3057468. PMID 20420945.

- ^ Wan G, Mathur R, Hu X, Zhang X, Lu X (September 2011). "miRNA response to DNA damage". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 36 (9): 478–484. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2011.06.002. PMC 3532742. PMID 21741842.

- ^ Tessitore A, Cicciarelli G, Del Vecchio F, Gaggiano A, Verzella D, Fischietti M, et al. (2014). "MicroRNAs in the DNA Damage/Repair Network and Cancer". International Journal of Genomics. 2014: 820248. doi:10.1155/2014/820248. PMC 3926391. PMID 24616890.

- ^ a b Schnekenburger M, Diederich M (March 2012). "Epigenetics Offer New Horizons for Colorectal Cancer Prevention". Current Colorectal Cancer Reports. 8 (1): 66–81. doi:10.1007/s11888-011-0116-z. PMC 3277709. PMID 22389639.

- ^ a b Valeri N, Gasparini P, Fabbri M, Braconi C, Veronese A, Lovat F, et al. (April 2010). "Modulation of mismatch repair and genomic stability by miR-155". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (15): 6982–6987. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.6982V. doi:10.1073/pnas.1002472107. JSTOR 25665289. PMC 2872463. PMID 20351277.

- ^ a b Truninger K, Menigatti M, Luz J, Russell A, Haider R, Gebbers JO, et al. (May 2005). "Immunohistochemical analysis reveals high frequency of PMS2 defects in colorectal cancer". Gastroenterology. 128 (5): 1160–1171. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2005.01.056. PMID 15887099.

- ^ a b c Zhang W, Zhang J, Hoadley K, Kushwaha D, Ramakrishnan V, Li S, et al. (June 2012). "miR-181d: a predictive glioblastoma biomarker that downregulates MGMT expression". Neuro-Oncology. 14 (6): 712–719. doi:10.1093/neuonc/nos089. PMC 3367855. PMID 22570426.

- ^ Spiegl-Kreinecker S, Pirker C, Filipits M, Lötsch D, Buchroithner J, Pichler J, et al. (January 2010). "O6-Methylguanine DNA methyltransferase protein expression in tumor cells predicts outcome of temozolomide therapy in glioblastoma patients". Neuro-Oncology. 12 (1): 28–36. doi:10.1093/neuonc/nop003. PMC 2940563. PMID 20150365.

- ^ a b Palmieri D, D'Angelo D, Valentino T, De Martino I, Ferraro A, Wierinckx A, et al. (August 2012). "Downregulation of HMGA-targeting microRNAs has a critical role in human pituitary tumorigenesis". Oncogene. 31 (34): 3857–3865. doi:10.1038/onc.2011.557. PMID 22139073.

- ^ Sgarra R, Rustighi A, Tessari MA, Di Bernardo J, Altamura S, Fusco A, et al. (September 2004). "Nuclear phosphoproteins HMGA and their relationship with chromatin structure and cancer". FEBS Letters. 574 (1–3): 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2004.08.013. PMID 15358530. S2CID 28903539.

- ^ Xu Y, Sumter TF, Bhattacharya R, Tesfaye A, Fuchs EJ, Wood LJ, et al. (May 2004). "The HMG-I oncogene causes highly penetrant, aggressive lymphoid malignancy in transgenic mice and is overexpressed in human leukemia". Cancer Research. 64 (10): 3371–3375. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0044. PMID 15150086. S2CID 34111491.

- ^ Baldassarre G, Battista S, Belletti B, Thakur S, Pentimalli F, Trapasso F, et al. (April 2003). "Negative regulation of BRCA1 gene expression by HMGA1 proteins accounts for the reduced BRCA1 protein levels in sporadic breast carcinoma". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 23 (7): 2225–2238. doi:10.1128/MCB.23.7.2225-2238.2003. PMC 150734. PMID 12640109.

- ^ Borrmann L, Schwanbeck R, Heyduk T, Seebeck B, Rogalla P, Bullerdiek J, Wisniewski JR (December 2003). "High mobility group A2 protein and its derivatives bind a specific region of the promoter of DNA repair gene ERCC1 and modulate its activity". Nucleic Acids Research. 31 (23): 6841–6851. doi:10.1093/nar/gkg884. PMC 290254. PMID 14627817.

- ^ a b c d Facista A, Nguyen H, Lewis C, Prasad AR, Ramsey L, Zaitlin B, et al. (April 2012). "Deficient expression of DNA repair enzymes in early progression to sporadic colon cancer". Genome Integrity. 3 (1): 3. doi:10.1186/2041-9414-3-3. PMC 3351028. PMID 22494821.

- ^ Malumbres M (2013). "miRNAs and cancer: an epigenetics view". Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 34 (4): 863–874. doi:10.1016/j.mam.2012.06.005. PMC 5791883. PMID 22771542.

- ^ Sampath D, Liu C, Vasan K, Sulda M, Puduvalli VK, Wierda WG, Keating MJ (February 2012). "Histone deacetylases mediate the silencing of miR-15a, miR-16, and miR-29b in chronic lymphocytic leukemia". Blood. 119 (5): 1162–1172. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-05-351510. PMC 3277352. PMID 22096249.

- ^ Human DNA Repair Genes, 15 April 2014, MD Anderson Cancer Center, University of Texas

- ^ Krishnan K, Steptoe AL, Martin HC, Wani S, Nones K, Waddell N, et al. (February 2013). "MicroRNA-182-5p targets a network of genes involved in DNA repair". RNA. 19 (2): 230–242. doi:10.1261/rna.034926.112. PMC 3543090. PMID 23249749.

- ^ Chaisaingmongkol J, Popanda O, Warta R, Dyckhoff G, Herpel E, Geiselhart L, et al. (December 2012). "Epigenetic screen of human DNA repair genes identifies aberrant promoter methylation of NEIL1 in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma". Oncogene. 31 (49): 5108–5116. doi:10.1038/onc.2011.660. PMID 22286769.

- ^ Liang L, Deng L, Chen Y, Li GC, Shao C, Tischfield JA (September 2005). "Modulation of DNA end joining by nuclear proteins". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 280 (36): 31442–31449. doi:10.1074/jbc.M503776200. PMID 16012167.

- ^ Singh P, Yang M, Dai H, Yu D, Huang Q, Tan W, et al. (November 2008). "Overexpression and hypomethylation of flap endonuclease 1 gene in breast and other cancers". Molecular Cancer Research. 6 (11): 1710–1717. doi:10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0269. PMC 2948671. PMID 19010819.

- ^ Lam JS, Seligson DB, Yu H, Li A, Eeva M, Pantuck AJ, et al. (August 2006). "Flap endonuclease 1 is overexpressed in prostate cancer and is associated with a high Gleason score". BJU International. 98 (2): 445–451. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06224.x. PMID 16879693. S2CID 22165252.

- ^ Kim JM, Sohn HY, Yoon SY, Oh JH, Yang JO, Kim JH, et al. (January 2005). "Identification of gastric cancer-related genes using a cDNA microarray containing novel expressed sequence tags expressed in gastric cancer cells". Clinical Cancer Research. 11 (2 Pt 1): 473–482. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.473.11.2. PMID 15701830.

- ^ Wang K, Xie C, Chen D (May 2014). "Flap endonuclease 1 is a promising candidate biomarker in gastric cancer and is involved in cell proliferation and apoptosis". International Journal of Molecular Medicine. 33 (5): 1268–1274. doi:10.3892/ijmm.2014.1682. PMID 24590400.

- ^ Krause A, Combaret V, Iacono I, Lacroix B, Compagnon C, Bergeron C, et al. (July 2005). "Genome-wide analysis of gene expression in neuroblastomas detected by mass screening" (PDF). Cancer Letters. 225 (1): 111–120. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2004.10.035. PMID 15922863. S2CID 44644467.

- ^ Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Maitra A, Olsen M, Lowe AW, van Heek NT, Rosty C, et al. (April 2003). "Exploration of global gene expression patterns in pancreatic adenocarcinoma using cDNA microarrays". The American Journal of Pathology. 162 (4): 1151–1162. doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63911-9. PMC 1851213. PMID 12651607.

- ^ Sato M, Girard L, Sekine I, Sunaga N, Ramirez RD, Kamibayashi C, Minna JD (October 2003). "Increased expression and no mutation of the Flap endonuclease (FEN1) gene in human lung cancer". Oncogene. 22 (46): 7243–7246. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1206977. PMID 14562054. S2CID 22443138.

- ^ Bi FF, Li D, Yang Q (2013). "Hypomethylation of ETS transcription factor binding sites and upregulation of PARP1 expression in endometrial cancer". BioMed Research International. 2013: 946268. doi:10.1155/2013/946268. PMC 3666359. PMID 23762867.

- ^ Li D, Bi FF, Cao JM, Cao C, Li CY, Liu B, Yang Q (January 2014). "Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 transcriptional regulation: a novel crosstalk between histone modification H3K9ac and ETS1 motif hypomethylation in BRCA1-mutated ovarian cancer". Oncotarget. 5 (1): 291–297. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.1549. PMC 3960209. PMID 24448423.

- ^ Bi FF, Li D, Yang Q (February 2013). "Promoter hypomethylation, especially around the E26 transformation-specific motif, and increased expression of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 in BRCA-mutated serous ovarian cancer". BMC Cancer. 13: 90. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-13-90. PMC 3599366. PMID 23442605.

- ^ Narayanan L, Fritzell JA, Baker SM, Liskay RM, Glazer PM (April 1997). "Elevated levels of mutation in multiple tissues of mice deficient in the DNA mismatch repair gene Pms2". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 94 (7): 3122–3127. Bibcode:1997PNAS...94.3122N. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.7.3122. JSTOR 41786. PMC 20332. PMID 9096356.

- ^ Hegan DC, Narayanan L, Jirik FR, Edelmann W, Liskay RM, Glazer PM (December 2006). "Differing patterns of genetic instability in mice deficient in the mismatch repair genes Pms2, Mlh1, Msh2, Msh3 and Msh6". Carcinogenesis. 27 (12): 2402–2408. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgl079. PMC 2612936. PMID 16728433.

- ^ Tutt AN, van Oostrom CT, Ross GM, van Steeg H, Ashworth A (March 2002). "Disruption of Brca2 increases the spontaneous mutation rate in vivo: synergism with ionizing radiation". EMBO Reports. 3 (3): 255–260. doi:10.1093/embo-reports/kvf037. PMC 1084010. PMID 11850397.

- ^ Halford S, Rowan A, Sawyer E, Talbot I, Tomlinson I (June 2005). "O(6)-methylguanine methyltransferase in colorectal cancers: detection of mutations, loss of expression, and weak association with G:C>A:T transitions". Gut. 54 (6): 797–802. doi:10.1136/gut.2004.059535. PMC 1774551. PMID 15888787.

- ^ Shen L, Kondo Y, Rosner GL, Xiao L, Hernandez NS, Vilaythong J, et al. (September 2005). "MGMT promoter methylation and field defect in sporadic colorectal cancer". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 97 (18): 1330–1338. doi:10.1093/jnci/dji275. PMID 16174854.

- ^ a b Lee KH, Lee JS, Nam JH, Choi C, Lee MC, Park CS, et al. (October 2011). "Promoter methylation status of hMLH1, hMSH2, and MGMT genes in colorectal cancer associated with adenoma-carcinoma sequence". Langenbeck's Archives of Surgery. 396 (7): 1017–1026. doi:10.1007/s00423-011-0812-9. PMID 21706233. S2CID 8069716.

- ^ Svrcek M, Buhard O, Colas C, Coulet F, Dumont S, Massaoudi I, et al. (November 2010). "Methylation tolerance due to an O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) field defect in the colonic mucosa: an initiating step in the development of mismatch repair-deficient colorectal cancers". Gut. 59 (11): 1516–1526. doi:10.1136/gut.2009.194787. PMID 20947886. S2CID 206950452.

- ^ Paluszczak J, Misiak P, Wierzbicka M, Woźniak A, Baer-Dubowska W (February 2011). "Frequent hypermethylation of DAPK, RARbeta, MGMT, RASSF1A and FHIT in laryngeal squamous cell carcinomas and adjacent normal mucosa". Oral Oncology. 47 (2): 104–107. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.11.006. PMID 21147548.

- ^ Zuo C, Zhang H, Spencer HJ, Vural E, Suen JY, Schichman SA, et al. (October 2009). "Increased microsatellite instability and epigenetic inactivation of the hMLH1 gene in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 141 (4): 484–490. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2009.07.007. PMID 19786217. S2CID 8357370.

- ^ Tawfik HM, El-Maqsoud NM, Hak BH, El-Sherbiny YM (2011). "Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: mismatch repair immunohistochemistry and promoter hypermethylation of hMLH1 gene". American Journal of Otolaryngology. 32 (6): 528–536. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2010.11.005. PMID 21353335.

- ^ Zou XP, Zhang B, Zhang XQ, Chen M, Cao J, Liu WJ (November 2009). "Promoter hypermethylation of multiple genes in early gastric adenocarcinoma and precancerous lesions". Human Pathology. 40 (11): 1534–1542. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2009.01.029. PMID 19695681.

- ^ Wani M, Afroze D, Makhdoomi M, Hamid I, Wani B, Bhat G, et al. (2012). "Promoter methylation status of DNA repair gene (hMLH1) in gastric carcinoma patients of the Kashmir valley". Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 13 (8): 4177–4181. doi:10.7314/APJCP.2012.13.8.4177. PMID 23098428.

- ^ a b Raza Y, Ahmed A, Khan A, Chishti AA, Akhter SS, Mubarak M, et al. (May 2020). "Helicobacter pylori severely reduces expression of DNA repair proteins PMS2 and ERCC1 in gastritis and gastric cancer". DNA Repair. 89: 102836. doi:10.1016/j.dnarep.2020.102836. PMID 32143126. S2CID 212622031.

- ^ Agarwal A, Polineni R, Hussein Z, Vigoda I, Bhagat TD, Bhattacharyya S, et al. (2012). "Role of epigenetic alterations in the pathogenesis of Barrett's esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma". International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology. 5 (5): 382–396. PMC 3396065. PMID 22808291.

- ^ Tuna M, Amos CI (November 2013). "Genomic sequencing in cancer". Cancer Letters. 340 (2): 161–170. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2012.11.004. PMC 3622788. PMID 23178448.

- ^ Roach JC, Glusman G, Smit AF, Huff CD, Hubley R, Shannon PT, et al. (April 2010). "Analysis of genetic inheritance in a family quartet by whole-genome sequencing". Science. 328 (5978): 636–639. Bibcode:2010Sci...328..636R. doi:10.1126/science.1186802. PMC 3037280. PMID 20220176.

- ^ Campbell CD, Chong JX, Malig M, Ko A, Dumont BL, Han L, et al. (November 2012). "Estimating the human mutation rate using autozygosity in a founder population". Nature Genetics. 44 (11): 1277–1281. doi:10.1038/ng.2418. PMC 3483378. PMID 23001126.

- ^ Keightley PD (February 2012). "Rates and fitness consequences of new mutations in humans". Genetics. 190 (2): 295–304. doi:10.1534/genetics.111.134668. PMC 3276617. PMID 22345605.

- ^ Ye K, Beekman M, Lameijer EW, Zhang Y, Moed MH, van den Akker EB, et al. (December 2013). "Aging as accelerated accumulation of somatic variants: whole-genome sequencing of centenarian and middle-aged monozygotic twin pairs". Twin Research and Human Genetics. 16 (6): 1026–1032. doi:10.1017/thg.2013.73. PMID 24182360.

- ^ Shanbhag NM, Rafalska-Metcalf IU, Balane-Bolivar C, Janicki SM, Greenberg RA (June 2010). "ATM-dependent chromatin changes silence transcription in cis to DNA double-strand breaks". Cell. 141 (6): 970–981. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.038. PMC 2920610. PMID 20550933.

- ^ Morano A, Angrisano T, Russo G, Landi R, Pezone A, Bartollino S, et al. (January 2014). "Targeted DNA methylation by homology-directed repair in mammalian cells. Transcription reshapes methylation on the repaired gene". Nucleic Acids Research. 42 (2): 804–821. doi:10.1093/nar/gkt920. PMC 3902918. PMID 24137009.

- ^ Fernandez AF, Assenov Y, Martin-Subero JI, Balint B, Siebert R, Taniguchi H, et al. (February 2012). "A DNA methylation fingerprint of 1628 human samples". Genome Research. 22 (2): 407–419. doi:10.1101/gr.119867.110. PMC 3266047. PMID 21613409.

- ^ Bishop JB, Witt KL, Sloane RA (December 1997). "Genetic toxicities of human teratogens". Mutation Research. 396 (1–2): 9–43. doi:10.1016/S0027-5107(97)00173-5. PMID 9434858.

- ^ Gurvich N, Berman MG, Wittner BS, Gentleman RC, Klein PS, Green JB (July 2005). "Association of valproate-induced teratogenesis with histone deacetylase inhibition in vivo". FASEB Journal. 19 (9): 1166–1168. doi:10.1096/fj.04-3425fje. PMID 15901671. S2CID 25874971.

- ^ Smithells D (November 1998). "Does thalidomide cause second generation birth defects?". Drug Safety. 19 (5): 339–341. doi:10.2165/00002018-199819050-00001. PMID 9825947. S2CID 9014237.

- ^ Friedler G (December 1996). "Paternal exposures: impact on reproductive and developmental outcome. An overview". Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 55 (4): 691–700. doi:10.1016/S0091-3057(96)00286-9. PMID 8981601. S2CID 2260876.

- ^ "Vidaza (azacitidine for injectable suspension) package insert" (PDF). Pharmion Corporation. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 18 May 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2004.

- ^ Cicero TJ, Adams ML, Giordano A, Miller BT, O'Connor L, Nock B (March 1991). "Influence of morphine exposure during adolescence on the sexual maturation of male rats and the development of their offspring". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 256 (3): 1086–1093. PMID 2005573.

- ^ Newbold RR, Padilla-Banks E, Jefferson WN (June 2006). "Adverse effects of the model environmental estrogen diethylstilbestrol are transmitted to subsequent generations". Endocrinology. 147 (6 Suppl): S11–S17. doi:10.1210/en.2005-1164. PMID 16690809.

- ^ a b Katiyar SK, Singh T, Prasad R, Sun Q, Vaid M (September 2012). "Epigenetic alterations in ultraviolet radiation-induced skin carcinogenesis: interaction of bioactive dietary components on epigenetic targets". Photochemistry and Photobiology. 88 (5): 1066–1074. doi:10.1111/j.1751-1097.2011.01020.x. PMC 3288155. PMID 22017262.

- ^ Orouji E, Utikal J (November 2018). "Tackling malignant melanoma epigenetically: histone lysine methylation". Clinical Epigenetics. 10 (1): 145. doi:10.1186/s13148-018-0583-z. PMC 6249913. PMID 30466474.

- ^ a b Collins CC, Volik SV, Lapuk AV, Wang Y, Gout PW, Wu C, et al. (March 2012). "Next generation sequencing of prostate cancer from a patient identifies a deficiency of methylthioadenosine phosphorylase, an exploitable tumor target". Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 11 (3): 775–783. doi:10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0826. PMC 3691697. PMID 22252602.

- ^ a b Li LC, Carroll PR, Dahiya R (January 2005). "Epigenetic changes in prostate cancer: implication for diagnosis and treatment". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 97 (2): 103–115. doi:10.1093/jnci/dji010. PMID 15657340.

- ^ a b Gurel B, Iwata T, Koh CM, Yegnasubramanian S, Nelson WG, De Marzo AM (November 2008). "Molecular alterations in prostate cancer as diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic targets". Advances in Anatomic Pathology. 15 (6): 319–331. doi:10.1097/PAP.0b013e31818a5c19. PMC 3214657. PMID 18948763.

- ^ Ornish D, Magbanua MJ, Weidner G, Weinberg V, Kemp C, Green C, et al. (June 2008). "Changes in prostate gene expression in men undergoing an intensive nutrition and lifestyle intervention". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (24): 8369–8374. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.8369O. doi:10.1073/pnas.0803080105. PMC 2430265. PMID 18559852.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Sun C, Reimers LL, Burk RD (April 2011). "Methylation of HPV16 genome CpG sites is associated with cervix precancer and cancer". Gynecologic Oncology. 121 (1): 59–63. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.01.013. PMC 3062667. PMID 21306759.

- ^ Mandal SS (April 2010). "Mixed lineage leukemia: versatile player in epigenetics and human disease". The FEBS Journal. 277 (8): 1789. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07605.x. PMID 20236314. S2CID 37705117.

- ^ Nebbioso A, Tambaro FP, Dell'Aversana C, Altucci L (June 2018). Greally GM (ed.). "Cancer epigenetics: Moving forward". PLOS Genetics. 14 (6): e1007362. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1007362. PMC 5991666. PMID 29879107.

- ^ Butcher J (March 2001). "Electromagnetic fields may cause leukaemia in children". The Lancet. 357 (9258): 777. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71207-1. S2CID 54400632.

- ^ "Soft Tissue Sarcoma". National Cancer Institute. National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. January 1980.

- ^ Bennani-Baiti IM (December 2011). "Epigenetic and epigenomic mechanisms shape sarcoma and other mesenchymal tumor pathogenesis". Epigenomics. 3 (6): 715–732. doi:10.2217/epi.11.93. PMID 22126291.

- ^ Richter GH, Plehm S, Fasan A, Rössler S, Unland R, Bennani-Baiti IM, et al. (March 2009). "EZH2 is a mediator of EWS/FLI1 driven tumor growth and metastasis blocking endothelial and neuro-ectodermal differentiation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (13): 5324–5329. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.5324R. doi:10.1073/pnas.0810759106. PMC 2656557. PMID 19289832.

- ^ Bennani-Baiti IM, Machado I, Llombart-Bosch A, Kovar H (August 2012). "Lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1/KDM1A/AOF2/BHC110) is expressed and is an epigenetic drug target in chondrosarcoma, Ewing's sarcoma, osteosarcoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma". Human Pathology. 43 (8): 1300–1307. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2011.10.010. PMID 22245111.

- ^ Tam, Kit W.; Zhang, Wei; Soh, Junichi; Stastny, Victor; Chen, Min; Sun, Han; Thu, Kelsie; Rios, Jonathan J.; Yang, Chenchen; Marconett, Crystal N.; Selamat, Suhaida. A.; Laird-Offringa, Ite A.; Taguchi, Ayumu; Hanash, Samir; Shames, David (2013-11-01). "CDKN2A/p16 Inactivation Mechanisms and Their Relationship to Smoke Exposure and Molecular Features in Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer". Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 8 (11): 1378–1388. doi:10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182a46c0c. ISSN 1556-0864. PMC 3951422. PMID 24077454.

- ^ Hong, Runyu; Liu, Wenke; Fenyö, David (2021). "Predicting and Visualizing STK11 Mutation in Lung Adenocarcinoma Histopathology Slides Using Deep Learning". doi:10.1101/2020.02.20.956557. Retrieved 2023-03-16.

- ^ Ahmad, Aamir (2015). Lung Cancer and Personalized Medicine: Novel Therapies and Clinical Management. Springer International Publishing. ISBN 978-3-319-24932-2. OCLC 1113687835.

- ^ Iwakawa, Reika; Kohno, Takashi; Anami, Yoichi; Noguchi, Masayuki; Suzuki, Kenji; Matsuno, Yoshihiro; Mishima, Kazuhiko; Nishikawa, Ryo; Tashiro, Fumio; Yokota, Jun (2008-06-15). "Association of p16 Homozygous Deletions with Clinicopathologic Characteristics and EGFR/KRAS/p53 Mutations in Lung Adenocarcinoma". Clinical Cancer Research. 14 (12): 3746–3753. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-07-4552. ISSN 1078-0432. PMID 18559592. S2CID 17931210.

- ^ Fountain, J. W.; Giendening, J. M.; Flores, J. F. (1994-09-01). "Characterization of the p16 gene in the mouse: Evidence for a large gene family". American Journal of Human Genetics. 55 (Suppl.3). OSTI 133832.

- ^ Esteller M, Herman JG (January 2004). "Generating mutations but providing chemosensitivity: the role of O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase in human cancer". Oncogene. 23 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1207316. PMID 14712205. S2CID 38574543.

- ^ Esteller M, Garcia-Foncillas J, Andion E, Goodman SN, Hidalgo OF, Vanaclocha V, et al. (November 2000). "Inactivation of the DNA-repair gene MGMT and the clinical response of gliomas to alkylating agents". The New England Journal of Medicine. 343 (19): 1350–1354. doi:10.1056/NEJM200011093431901. hdl:2445/176306. PMID 11070098. S2CID 40303322.

- ^ Hegi ME, Diserens AC, Gorlia T, Hamou MF, de Tribolet N, Weller M, et al. (March 2005). "MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma" (PDF). The New England Journal of Medicine. 352 (10): 997–1003. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa043331. PMID 15758010.

- ^ Esteller M, Gaidano G, Goodman SN, Zagonel V, Capello D, Botto B, et al. (January 2002). "Hypermethylation of the DNA repair gene O(6)-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase and survival of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 94 (1): 26–32. doi:10.1093/jnci/94.1.26. PMID 11773279.

- ^ Glasspool RM, Teodoridis JM, Brown R (April 2006). "Epigenetics as a mechanism driving polygenic clinical drug resistance". British Journal of Cancer. 94 (8): 1087–1092. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6603024. PMC 2361257. PMID 16495912.

- ^ Brock MV, Hooker CM, Ota-Machida E, Han Y, Guo M, Ames S, et al. (March 2008). "DNA methylation markers and early recurrence in stage I lung cancer". The New England Journal of Medicine. 358 (11): 1118–1128. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0706550. PMID 18337602. S2CID 18279123.

- ^ a b Iglesias-Linares A, Yañez-Vico RM, González-Moles MA (May 2010). "Potential role of HDAC inhibitors in cancer therapy: insights into oral squamous cell carcinoma". Oral Oncology. 46 (5): 323–329. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.01.009. PMID 20207580.

- ^ Wang LG, Chiao JW (September 2010). "Prostate cancer chemopreventive activity of phenethyl isothiocyanate through epigenetic regulation (review)". International Journal of Oncology. 37 (3): 533–539. doi:10.3892/ijo_00000702. PMID 20664922.