Canadian Foundation for Children, Youth and the Law v Canada (AG)

| Canadian Foundation for Children, Youth and the Law v Canada (AG) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Hearing: June 6, 2003 Judgment: January 30, 2004 | |

| Full case name | Canadian Foundation for Children, Youth and the Law v. Attorney General in Right of Canada |

| Citations | [2004] 1 S.C.R. 76, 2004 SCC 4 |

| Docket No. | 29113 [1] |

| Prior history | Judgment for the Attorney General of Canada in the Court of Appeal for Ontario. |

| Ruling | Appeal dismissed. |

| Holding | |

| Section 43 of the Criminal Code (which allows parents and teachers to use force to correct a child's behaviour) does not infringe the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, provided the section is interpreted as follows: (1) The force must be intended to actually correct the child's behaviour. (2) The force cannot result in harm or the prospect of harm. | |

| Court membership | |

| Chief Justice: Beverley McLachlin Puisne Justices: Charles Gonthier, Frank Iacobucci, John C. Major, Michel Bastarache, Ian Binnie, Louise Arbour, Louis LeBel, Marie Deschamps | |

| Reasons given | |

| Majority | McLachlin C.J. (paras. 1-70), joined by Gonthier, Iacobucci, Major, Bastarache and LeBel JJ. |

| Concur/dissent | Binnie J. (paras. 71-130) |

| Dissent | Arbour J. (paras. 131-211) |

| Dissent | Deschamps J. (paras. 212-246) |

| Part of a series on |

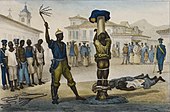

| Corporal punishment |

|---|

|

| By place |

| By implementation |

| By country |

| Court cases |

| Politics |

| Campaigns against corporal punishment |

Canadian Foundation for Children, Youth and the Law v Canada (AG), [2004] 1 S.C.R. 76, 2004 SCC 4 – known also as the spanking case – is a leading Charter decision of the Supreme Court of Canada where the Court upheld section 43 of the Criminal Code that allowed for a defence of reasonable use of force by way of correction towards children as not in violation of section 7, section 12 or section 15(1) of the Charter.

Background

[edit]The Canadian Foundation for Children, Youth and the Law applied for a declaration to strike-down section 43 of the Criminal Code which states, under the section entitled "Protection of Persons in Authority",

43. Every schoolteacher, parent or person standing in the place of a parent is justified in using force by way of correction toward a pupil or child, as the case may be, who is under his care, if the force does not exceed what is reasonable under the circumstances.

The basis of which is because the provision violates:

- section 7 of the Canadian Charter because it fails to give procedural protections to children, does not further the best interests of the child, and is both overbroad and vague;

- section 12 of the Charter because it constitutes cruel and unusual punishment or treatment;

- section 15(1) of the Charter because it denies children the legal protection against assaults that is accorded to adults.

Ruling

[edit]The Supreme Court handed down its 6 to 3 decision on January 30, 2004.

The majority opinion was written by Chief Justice McLachlin with Gonthier, Iacobucci, Major, Bastarache and LeBel JJ. concurring.

Limits on reasonableness

[edit]The court first defined what types of force could be considered reasonable in the circumstances, the court held that in order for corporal punishment to be considered reasonable it could only be used for corrective purposes against children capable of appreciating it, could only be "transitory and trifling" in nature, and could not be done in a degrading or harmful manner. The court ruled that in order to be protected by section 43 and not be considered assault, corporal punishment must:

- be done by a parent or someone in the standing of a parent (effectively outlawing corporal punishment in schools),

- only be used against children between the ages of two and twelve,

- not be conducted in a manner that either causes or has the potential to cause harm, including bruising or marks,

- not be used out of frustration, loss of temper, or because of the caregiver's abusive personality,

- not be conducted with objects, like belts or rulers,

- not hit the child on the head

- not be done in a manner that is otherwise degrading, inhumane, or harmful, and

- not be used against children with disabilities that make them incapable of appreciating the punishment.

Section 7

[edit]Section 7 protects individuals from violation of their personal security. McLachlin found that there was no violation of the section. The Crown had conceded that the law adversely affected the child's security of person, so the issue was whether the violation offended a principle of fundamental justice. The Foundation proposed three claims as mentioned above. McLachlin rejected the first claim that it failed to give procedural protection as children receive all the same protection as anyone else. On the second claim, she rejected that the "best interests of the child" is a principle of fundamental justice as there is no "consensus that it is vital or fundamental to our societal notion of justice".

On the third, she rejected the claim that the law is vague and overbroad on grounds that the law "delineates a risk zone for criminal sanction". She examined the meaning of "reasonable under the circumstances" stating that it included only "minor corrective force of a transitory and trifling nature", but it did not include "corporal punishment of children under two or teenagers", or "degrading, inhuman or harmful conduct" such as "discipline by the use of objects", "blows or slaps to the head" or acts of anger. The test is purely objective, McLachlin claimed.

Section 12

[edit]Section 12 prevents "cruel and unusual punishment". Citing the standard of showing cruel and unusual punishment from R. v. Smith [1987] 1 S.C.R. 1045 as "so excessive as to outrage standards of decency", McLachlin rejected the claim as the section only permits "corrective force that is reasonable" and thus cannot be excessive by definition.

Section 15(1)

[edit]Section 15(1) is the equality guarantee that protects individuals from discrimination. McLachlin examined the claim using the analytical framework from Law v. Canada.

When identifying from whose perspective the analysis must be, McLachlin noted that rather than take the perspective of a young child, which would prove too difficult, it must be viewed from the perspective of a "reasonable person acting on behalf of a child" and apprised of the law.

McLachlin said that the claim hinges on demonstrating the lack of "correspondence between the distinction and the claimant's characteristics or circumstances" (the second contextual factor from the Law v. Canada test). On this point she acknowledged that children need to be protected, and in furtherance of this goal parents and teachers require protection as well. Section 43 decriminalizes "only minimal force of transient or trivial impact" and to remove such protection would be dangerous as it would criminalize acts such as "placing an unwilling child in a chair for a five-minute 'time-out'" which would risk destroying the family.

See also

[edit]External links

[edit]- Full text of Supreme Court of Canada decision available at LexUM and CanLII

- Parliament publication on section 43 of the Criminal Code Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ SCC Case Information - Docket 29113 Supreme Court of Canada