COVID-19 drug development

| Part of a series on the |

| COVID-19 pandemic |

|---|

|

|

|

|

COVID-19 drug development is the research process to develop preventative therapeutic prescription drugs that would alleviate the severity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). From early 2020 through 2021, several hundred drug companies, biotechnology firms, university research groups, and health organizations were developing therapeutic candidates for COVID-19 disease in various stages of preclinical or clinical research (506 total candidates in April 2021), with 419 potential COVID-19 drugs in clinical trials, as of April 2021.[1]

As early as March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO),[2] European Medicines Agency (EMA),[3] US Food and Drug Administration (FDA),[4] and the Chinese government and drug manufacturers[5][6] were coordinating with academic and industry researchers to speed development of vaccines, antiviral drugs, and post-infection therapies.[7][8][9][10] The International Clinical Trials Registry Platform of the WHO recorded 536 clinical studies to develop post-infection therapies for COVID-19 infections,[11][12] with numerous established antiviral compounds for treating other infections under clinical research to be repurposed.[7][13][14][15]

In March 2020, the WHO initiated the "SOLIDARITY Trial" in 10 countries, enrolling thousands of people infected with COVID-19 to assess treatment effects of four existing antiviral compounds with the most promise of efficacy.[2][16] A dynamic, systematic review was established in April 2020 to track the progress of registered clinical trials for COVID-19 vaccine and therapeutic drug candidates.[12]

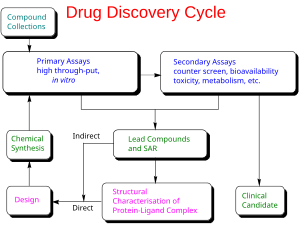

Drug development is a multistep process, typically requiring more than five years to assure safety and efficacy of the new compound.[17] Several national regulatory agencies, such as the EMA and the FDA, approved procedures to expedite clinical testing.[4][18] By June 2021, dozens of potential post-infection therapies were in the final stage of human testing – phase III–IV clinical trials.[19]

Background

Drug development is the process of bringing a new infectious disease vaccine or therapeutic drug to the market once a lead compound has been identified through the process of drug discovery.[17] It includes laboratory research on microorganisms and animals, filing for regulatory status, such as via the FDA, for an investigational new drug to initiate clinical trials on humans, and may include the step of obtaining regulatory approval with a new drug application to market the drug.[20][21] The entire process – from concept through preclinical testing in the laboratory to clinical trial development, including Phase I–III trials – to approved vaccine or drug normally takes more than a decade.[17][20][21]

The term "preclinical research" is defined by laboratory studies in vitro and in vivo, indicating a beginning stage for development of a preventative vaccine, antiviral or other post-infection therapies,[7] such as experiments to determine effective doses and toxicity in animals, before a candidate compound is advanced for safety and efficacy evaluation in humans.[22] To complete the preclinical stage of drug development – then be tested for safety and efficacy in an adequate number of people infected with COVID-19 (hundreds to thousands in different countries) – is a process likely to require 1–2 years for COVID-19 therapies, according to several reports in early 2020.[9][23][24][25] Despite these efforts, the success rate for drug candidates to reach eventual regulatory approval through the entire drug development process for treating infectious diseases is only 19%.[26]

Phase I trials test primarily for safety and preliminary dosing in a few dozen healthy subjects, while Phase II trials – following success in Phase I – evaluate therapeutic efficacy against the COVID-19 disease at ascending dose levels (efficacy based on biomarkers), while closely evaluating possible adverse effects of the candidate therapy (or combined therapies), typically in hundreds of people. A common trial design for Phase II studies of possible COVID-19 drugs is randomized, placebo-controlled, blinded, and conducted at multiple sites, while determining more precise, effective doses and monitoring for adverse effects.[27]

The success rate for Phase II trials to advance to Phase III (for all diseases) is about 31%, and for infectious diseases specifically, about 43%.[26] Depending on its duration (longer more expensive) – typically a period of several months to two years[27] – an average-length Phase II trial costs US$57 million (2013 dollars, including preclinical and Phase I costs).[28] Successful completion of a Phase II trial does not reliably forecast that a candidate drug will be successful in Phase III research.[29]

Phase III trials for COVID-19 involve hundreds-to-thousands of hospitalized participants, and test effectiveness of the treatment to reduce effects of the disease, while monitoring for adverse effects at the optimal dose, such as in the multinational Solidarity and Discovery trials.[2][17][30]

Candidates

This section needs to be updated. (February 2021) |

According to one source (as of August 2020), diverse categories of preclinical or early-stage clinical research for developing COVID-19 therapeutic candidates included:[19]

- antibodies (81 candidates)

- antivirals (31 candidates)

- cell-based compounds (34 candidates)

- RNA-based compounds (6 candidates)

- scanning compounds to be repurposed (18 candidates)

- various other therapy categories, such as anti-inflammatory, antimalarial, interferon, protein-based, antibiotics, and receptor-modulating compounds.[19]

Pivotal Phase III trials assess whether a candidate drug has efficacy specifically against a disease, and – in the case of people hospitalized with severe COVID-19 infections – test for an effective dose level of the repurposed or new drug candidate to improve the illness (primarily pneumonia) from COVID-19 infection.[2][11][32] For an already-approved drug (such as hydroxychloroquine for malaria), Phase III–IV trials determine in hundreds to thousands of COVID-19-infected people the possible extended use of an already-approved drug for treating COVID-19 infection.[32] As of August 2020, over 500 candidate therapeutics were in preclinical or a stage of Phase I–IV development, with new Phase II–III trials announced for hundreds of therapeutic candidates during 2020.[19]

Numerous candidate drugs under study as "supportive" treatments to relieve discomfort during illness, such as NSAIDs or bronchodilators, are not included in the table below. Others in early-stage Phase II trials or numerous treatment candidates in Phase I trials,[19] are also excluded. Drug candidates in Phase I–II trials have a low rate of success (under 12%) to pass through all trial phases to gain eventual approval.[20][29] Once having reached Phase III trials, therapeutic candidates for diseases related to COVID-19 infection – infectious and respiratory diseases – have a success rate of about 72%.[26]

| Drug candidate | Description | Existing disease approval | Trial sponsor(s) | Location(s) | Expected results | Notes, references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Remdesivir | antiviral; adenosine nucleotide analog inhibiting RNA synthesis in coronaviruses | investigational[33] | Gilead, WHO, INSERM, NIAID | China, Japan initially; extended internationally in Global Solidarity and Discovery Trials, and US NIAID ACTT Trial | Mid-2020 (Chinese, Japanese trials) | [19][34][35] selectively provided by Gilead for COVID-19 emergency access;[36][37] both promising and negative effects reported in April 2020.[38][39][40] |

| Hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine | antiparasitic and antirheumatic; generic made by many manufacturers | malaria, rheumatoid arthritis, lupus (International)[41][42] | CEPI, WHO, INSERM | Multiple sites in China; global Solidarity and Discovery Trials | June 2020 (discontinued by WHO) | multiple side effects; possible adverse prescription drug interactions;[41][42] discontinued in June from WHO Solidarity trial and UK Recovery trial as "having no clinical benefit in hospitalised patients with COVID-19";[43][44] trials[19][34] |

| Favipiravir | antiviral against influenza | influenza (China)[45] | Fujifilm | China | April 2020 | [19][8][46] |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir without or with interferon beta-1a | antiviral, immune suppression | investigational combination; lopinavir/ritonavir approved for HIV[47] | CEPI, WHO, UK Government, Univ. of Oxford, INSERM | Global Solidarity and Discovery Trials, multiple countries | mid-2020 | [19][34] |

| Sarilumab | human monoclonal antibody against interleukin-6 receptor | rheumatoid arthritis (US, Europe)[48] | Regeneron-Sanofi | Multiple countries | Spring 2020 | [19][49] |

| ASC-09 + ritonavir | antiviral | combination not approved; ritonavir approved for HIV[47] | Ascletis Pharma | Multiple sites in China | Spring 2020 | [19][50] |

| Tocilizumab | human monoclonal antibody against interleukin-6 receptor | immunosuppression, rheumatoid arthritis (US, Europe)[51] | Genentech-Hoffmann-La Roche | Multiple countries | mid-2020 | [19][52] Roche announced in late July that its Phase III trial of tocilizumab for treating pneumonia in hospitalized people with COVID-19 infection was ineffective[53] |

| Lenzilumab | humanized monoclonal antibody for relieving pneumonia | new drug candidate | Humanigen, Inc. | Multiple sites in the United States | September 2020 | [19][54] |

| Dapagliflozin | sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor | hypoglycemia agent[55] | Saint Luke's Mid America Heart Institute, AstraZeneca | Multiple countries | December 2020 | [19][56] |

| CD24Fc | antiviral immunomodulator against inflammatory response | new drug candidate | OncoImmune, Inc. | Multiple sites in the United States | 2021 | [19][57] |

| Apabetalone | selective BET inhibitor | investigational | Resverlogix Corp | United States | 22 March 2022 | [19][58] |

Repurposed drug candidates

Drug repositioning (also called drug repurposing) – the investigation of existing drugs for new therapeutic purposes – is one line of scientific research followed to develop safe and effective COVID-19 treatments.[15][59] Several existing antiviral medications, previously developed or used as treatments for Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), HIV/AIDS, and malaria, are being researched as COVID-19 treatments, with some moving into clinical trials.[13]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, drug repurposing is the clinical research process of rapidly screening and defining the safety and efficacy of existing drugs already approved for other diseases to be used for people with COVID-19 infection.[13][15][60] In the usual drug development process,[17] confirmation of repurposing for new disease treatment would take many years of clinical research – including pivotal Phase III clinical trials – on the candidate drug to assure its safety and efficacy specifically for treating COVID-19 infection.[13][60] In the emergency of a growing COVID-19 pandemic, the drug repurposing process was being accelerated during March 2020 to treat people hospitalized with COVID-19.[2][13][15]

Clinical trials using repurposed, generally safe, existing drugs for hospitalized COVID-19 people may take less time and have lower overall costs to obtain endpoints proving safety (absence of serious side effects) and post-infection efficacy, and can rapidly access existing drug supply chains for manufacturing and worldwide distribution.[2][13][61] In an international effort to capture these advantages, the WHO began in mid-March 2020 expedited international Phase II–III trials on four promising treatment options – the SOLIDARITY trial[2][62][63] – with numerous other drugs having potential for repurposing in different disease treatment strategies, such as anti-inflammatory, corticosteroid, antibody, immune, and growth factor therapies, among others, being advanced into Phase II or III trials during 2020.[19][13][60][64]

In March 2020, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued a physician advisory concerning remdesivir for people hospitalized with pneumonia caused by COVID-19: "While clinical trials are critical to establish the safety and efficacy of this drug, clinicians without access to a clinical trial may request remdesivir for compassionate use through the manufacturer for patients with clinical pneumonia."[37]

Novel antibody drugs

Convalescent plasma

Passive immunization with convalescent plasma or hyperimmune serum has been proposed as a potential treatment for COVID-19. As of May 2021, there is strong evidence that convalescent plasma treatment is not associated with clinical improvements for people with moderate or severe disease and does not decrease the risk of dying.[65] The potential for adverse effects associated with convalescent plasma treatment is unknown.[65]

In the United States, the FDA has granted temporary authorization to convalescent plasma (plasma from the blood of people who have recovered from COVID-19, which thus contains antibodies against SARS-CoV-2) as an experimental treatment in cases where the person's life is seriously or immediately threatened.[66] As of May 2021, at least 12 randomized controlled trials on the effectiveness of convalescent plasma treatment were published in peer-reviewed medical journals.[65] In addition, as of May 2021, 100 additional trials were 'ongoing' and 33 studies were reported as 'competed' but not yet published.[65]

Argentina, Brazil, Costa Rica, and Mexico have pursued development of antisera.[67] Brazil began development of an equine hyperimmune serum, obtained by inoculating horses with recombinant SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, in mid-2020. A consortium of Instituto Vital Brazil, UFRJ, the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation and the D'Or Institute for Research and Education in Rio de Janeiro began preclinical trials in May 2020,[68] while Instituto Butantan in São Paulo completed animal testing in September.[67] In December 2020, Argentina granted emergency authorization to CoviFab, a locally developed formulation of equine hyperimmune serum, for use in cases of moderate to severe COVID-19, based on the initial results of a single phase 2/3 trial which suggested reductions in mortality, ICU admission, and mechanical ventilation requirements in patients who received the serum.[69][70] This was harshly criticized by the Argentine Intensive Care Society, which stated that the trial failed to achieve its primary or secondary endpoints and did not demonstrate any statistically significant differences between the serum and placebo groups.[70]

Bamlanivimab/etesevimab

Bamlanivimab/etesevimab is a combination of two monoclonal antibodies, bamlanivimab and etesevimab, administered together via intravenous infusion as a treatment for COVID-19.[71][72][73][74] Both types of antibody target the surface spike protein of SARS‑CoV‑2.[75][76]

Bamlanivimab and etesevimab, administered together, are authorized in the United States for the treatment of mild-to-moderate COVID-19 in people aged twelve years of age and older weighing at least 40 kilograms (88 lb) with positive results of direct SARS-CoV-2 viral testing, and who are at high risk for progression to severe COVID-19, including hospitalization or death.[77][78] They are also authorized, when administered together, for use after exposure to the SARS-CoV-2 virus for post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) for COVID-19 and are not authorized for pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent COVID-19 before being exposed to the SARS-CoV-2 virus.[77][78]

In January 2022, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) revised the authorizations for two monoclonal antibody treatments – bamlanivimab/etesevimab (administered together) and casirivimab/imdevimab – to limit their use to only when the recipients are likely to have been infected with or exposed to a variant that is susceptible to these treatments.[79] Because data show these treatments are highly unlikely to be active against the omicron variant, which is circulating at a very high frequency throughout the United States, these treatments are not authorized for use in any U.S. states, territories, and jurisdictions at this time.[79]Bebtelovimab

Bebtelovimab is a monoclonal antibody developed by AbCellera and Eli Lilly as a treatment for COVID-19.[80][81][82][83]

Possible side effects include itching, rash, infusion-related reactions, nausea and vomiting.[80]

Bebtelovimab works by binding to the spike protein of the virus that causes COVID-19, similar to other monoclonal antibodies that have been authorized for the treatment of high-risk people with mild to moderate COVID-19 and shown a benefit in reducing the risk of hospitalization or death.[80] Bebtelovimab is a neutralizing human immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) monoclonal antibody, isolated from a patient who has recovered from the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), directed against the spike (S) protein of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), that can potentially be used for immunization against COVID-19.[84]

As of November 2022[update], bebtelovimab is not authorized for emergency use in the US because it is not expected to neutralize Omicron subvariants BQ.1 and BQ.1.1.[85]Casirivimab/imdevimab

Casirivimab/imdevimab, sold under the brand name REGEN‑COV among others,[86][87] is a combination medicine used for the treatment and prevention of COVID‑19.[87] It consists of two human monoclonal antibodies, casirivimab and imdevimab that must be mixed together and administered as an infusion or subcutaneous injection.[88][86][87] The combination of two antibodies is intended to prevent mutational escape.[89] It is also available as a co-formulated product.[88] It was developed by the American biotechnology company Regeneron Pharmaceuticals.[90][91]

The most common side effects include allergic reactions, which include infusion related reactions, injection site reactions,[87] brief pain, weakness and others.[92]

The combination is approved under the brand name Ronapreve for medical use in Japan, the United Kingdom, the European Union, and Australia.[93][94][87][95][96][97]

In January 2022, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) revised the authorizations for two monoclonal antibody treatments – bamlanivimab/etesevimab (administered together) and casirivimab/imdevimab – to limit their use to only when the recipients are likely to have been infected with or exposed to a variant that is susceptible to these treatments because data show these treatments are highly unlikely to be active against the omicron variant.[98]Pemivibart

Pemivibart, sold under the brand name Pemgarda, is a monoclonal antibody medication authorized for the pre-exposure prophylaxis (prevention) of COVID‑19.[99] Pemivibart was developed by Invivyd.[100][101]

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued an emergency use authorization for pemivibart in March 2024.[99][101]Regdanvimab

Regdanvimab, sold under the brand name Regkirona, is a human monoclonal antibody used for the treatment of COVID-19.[102] The antibody is directed against the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2. It is developed by Celltrion.[103][104] The medicine is given by infusion (drip) into a vein.[102][105]

The most common side effects include infusion-related reactions, including allergic reactions and anaphylaxis.[102]

Regdanvimab was approved for medical use in the European Union in November 2021.[102][106]Sotrovimab

Sotrovimab, sold under the brand name Xevudy, is a human neutralizing monoclonal antibody with activity against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, known as SARS-CoV-2.[107][108][109] It was developed by GlaxoSmithKline and Vir Biotechnology, Inc.[108][110] Sotrovimab is designed to attach to the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2.[108][109][111]

The most common side effects include hypersensitivity (allergic) reactions and infusion-related reactions.[107]

Although Sotrovimab was used world-wide against SARS-CoV-2, including in the United States under an FDA emergency use authorization (EUA), the FDA canceled the EUA in April 2022 due to lack of efficacy against the Omicron variant. [112]Tixagevimab/cilgavimab

Tixagevimab/cilgavimab, sold under the brand name Evusheld, is a combination of two human monoclonal antibodies, tixagevimab (AZD8895) and cilgavimab (AZD1061) targeted against the surface spike protein of SARS-CoV-2[113][114] used to prevent COVID-19.[115] It is being developed by British-Swedish multinational pharmaceutical and biotechnology company AstraZeneca.[116][117] It is co-packaged and given as two separate consecutive intramuscular injections (one injection per monoclonal antibody, given in immediate succession).[118]

Vilobelimab

Vilobelimab, sold under the brand name Gohibic, is an investigational medication that is used for the treatment of COVID-19.[119] It is a human-mouse chimeric IgG4 kappa antibody that targets human C5a in plasma.[120]

The most common adverse reactions include pneumonia, sepsis, delirium, pulmonary embolism, hypertension, pneumothorax, deep vein thrombosis, herpes simplex, enterococcal infection, bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, hepatic enzyme increased, urinary tract infection, hypoxia, thrombocytopenia, pneumomediastinum, respiratory tract infection, supraventricular tachycardia, constipation, and rash.[119]

Vilobelimab is a recombinant chimeric monoclonal IgG4 antibody that specifically binds to the soluble human complement split product C5a after cleavage from C5 to block its interaction with the C5a receptor, both of which are components of the complement system thought to contribute to inflammation and worsening of COVID-19.[121] Vilobelimab was granted an emergency use authorization (EUA) by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in April 2023.[119][121][120][122][123]Novel viral replication inhibitors

Molnupiravir

Molnupiravir, sold under the brand name Lagevrio, is an antiviral medication that inhibits the replication of certain RNA viruses.[124] It is used to treat COVID‑19 in those infected by SARS-CoV-2.[124] It is taken by mouth.[124]

Molnupiravir is a prodrug of the synthetic nucleoside derivative N4-hydroxycytidine and exerts its antiviral action by introducing copying errors during viral RNA replication.[125][126]

Molnupiravir was originally developed to treat influenza at Emory University by the university's drug innovation company, Drug Innovation Ventures at Emory (DRIVE), but was reportedly abandoned for mutagenicity concerns.[127][128] It was then acquired by the Miami-based company Ridgeback Biotherapeutics, which later partnered with Merck & Co. to develop the drug further.[129]

Based on positive results in placebo-controlled double-blind randomized clinical trials,[130][131] molnupiravir was approved for medical use in the United Kingdom in November 2021.[124][132][133][134] In December 2021, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted an emergency use authorization (EUA) to molnupiravir for use in certain populations where other treatments are not feasible.[135] The emergency use authorization was only narrowly approved (13–10) because of questions about efficacy and concerns that molnupiravir's mutagenic effects could create new variants that evade immunity and prolong the COVID‑19 pandemic.[136][137][138] In September 2023, molnupiravir's vial mutagenicity was confirmed to contribute to circulating SARS-CoV-2 genomic variation in a study of global SARS CoV 2 isolates after 2022: molnupiravir-specific genomic changes were more common, especially where molnupiravir had been used.[139]Novel protease inhibitors

Ensitrelvir

Ensitrelvir, sold under the brand name Xocova is an antiviral medication used as a treatment for COVID-19.[140][141][142][143] It was developed by Shionogi in partnership with Hokkaido University and acts as an orally active 3C-like protease inhibitor.[144][145] It is taken by mouth.[146][147][148]

The most common adverse events include transient decreases in high-density lipoprotein and increases blood triglycerides.[146]Nirmatrelvir/ritonavir

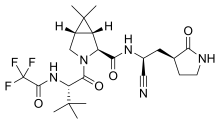

Nirmatrelvir/ritonavir, sold under the brand name Paxlovid, is a co-packaged medication used as a treatment for COVID‑19.[149][150][151][152] It contains the antiviral medications nirmatrelvir and ritonavir and was developed by Pfizer.[149][151] Nirmatrelvir inhibits SARS-CoV-2 main protease, while ritonavir is a strong CYP3A inhibitor, slowing down nirmatrelvir metabolism and therefore boosting its effect.[151][153] It is taken by mouth.[151]

In unvaccinated high-risk people with COVID‑19, nirmatrelvir/ritonavir can reduce the risk of hospitalization or death by 88% if taken within five days of symptom onset.[154] People who take nirmatrelvir/ritonavir also test negative for COVID‑19 about two and a half days earlier than people who do not.[155] Side effects of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir include changes in sense of taste (dysgeusia), diarrhea, high blood pressure (hypertension), and muscle pain (myalgia).[151]

In December 2021, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted nirmatrelvir/ritonavir emergency use authorization (EUA) to treat COVID‑19.[156][157] It was approved in the United Kingdom later that month,[158] and in the European Union and Canada in January 2022.[159][160][161] In May 2023, it was approved in the U.S. to treat mild to moderate COVID‑19 in adults who are at high risk for progression to severe COVID‑19, including hospitalization or death.[162][152] The FDA considers the combination to be a first-in-class medication.[163] In 2022, it was the 164th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 3 million prescriptions.[164][165]Other

Sabizabulin

Sabizabulin is an investigational new drug that is being evaluated for the treatment of castration-resistant prostate cancer[166] and in SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) infections.[167] It is a tubulin polymerization inhibitor.[168][169]

Sabizabulin is chemical compound from the group of indole and imidazole derivatives that was first reported in 2012 by Dalton, Li, and Miller.[170]Planning and coordination

This section needs to be updated. (June 2021) |

Early planning

Over 2018–20, new initiatives to stimulate vaccine and antiviral drug development included partnerships between governmental organizations and industry, such as the European Innovative Medicines Initiative,[171] the US Critical Path Initiative to enhance innovation of drug development,[172] and the Breakthrough Therapy designation to expedite development and regulatory review of promising candidate drugs.[173] To accelerate refinement of diagnostics for detecting COVID-19 infection, a global diagnostic pipeline tracker was formed.[174]

According to a tracker of clinical trial progress on potential therapeutic drugs for COVID-19 infections, 29 Phase II–IV efficacy trials were concluded in March 2020 or scheduled to provide results in April from hospitals in China – which experienced the first outbreak of COVID-19 in late 2019.[19] Seven trials were evaluating repurposed drugs already approved to treat malaria, including four studies on hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine phosphate.[19] Repurposed antiviral drugs make up most of the Chinese research, with 9 Phase III trials on remdesivir across several countries due to report by the end of April.[19] Other potential therapeutic candidates under pivotal clinical trials concluding in March–April are vasodilators, corticosteroids, immune therapies, lipoic acid, bevacizumab, and recombinant angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, among others.

The COVID-19 Clinical Research Coalition has goals to 1) facilitate rapid reviews of clinical trial proposals by ethics committees and national regulatory agencies, 2) fast-track approvals for the candidate therapeutic compounds, 3) ensure standardised and rapid analysis of emerging efficacy and safety data, and 4) facilitate sharing of clinical trial outcomes before publication.[11] A dynamic review of clinical development for COVID-19 vaccine and drug candidates was in place, as of April.[12]

By March 2020, the international Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) committed to research investments of US$100 million across several countries,[175] and issued an urgent call to raise and rapidly invest $2 billion for vaccine development.[176] Led by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation with partners investing US$125 million and coordinating with the World Health Organization, the COVID-19 Therapeutics Accelerator began in March, facilitating drug development researchers to rapidly identify, assess, develop, and scale up potential treatments.[177] The COVID-19 Clinical Research Coalition formed to coordinate and expedite results from international clinical trials on the most promising post-infection treatments.[11] In early 2020, numerous established antiviral compounds for treating other infections were being repurposed or developed in new clinical research efforts to alleviate the illness of COVID-19.[7][13][19]

During March 2020, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) initiated an international COVID-19 vaccine development fund, with the goal to raise US$2 billion for vaccine research and development,[178] and committed to investments of US$100 million in vaccine development across several countries.[175] The Canadian government announced CA$275 million in funding for 96 research projects on medical countermeasures against COVID-19, including numerous vaccine candidates at Canadian universities,[179][180] with plans to establish a "vaccine bank" of new vaccines for implementation if another COVID-19 outbreak occurs.[180][181] The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation invested US$150 million in April for development of COVID-19 vaccines, diagnostics, and therapeutics.[182]

Computer-assisted research

This section needs to be updated. (November 2020) |

In March 2020, the United States Department of Energy, National Science Foundation, NASA, industry, and nine universities pooled resources to access supercomputers from IBM, combined with cloud computing resources from Hewlett Packard Enterprise, Amazon, Microsoft, and Google, for drug discovery.[183][184] The COVID-19 High Performance Computing Consortium also aims to forecast disease spread, model possible vaccines, and screen thousands of chemical compounds to design a COVID-19 vaccine or therapy.[183][184] The Consortium used up 437 petaFLOPS of computing power by May 2020.[185]

The C3.ai Digital Transformation Institute, an additional consortium of Microsoft, six universities (including the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a member of the first consortium), and the National Center for Supercomputer Applications in Illinois, working under the auspices of C3.ai, an artificial intelligence software company, are pooling supercomputer resources toward drug discovery, medical protocol development and public health strategy improvement, as well as awarding large grants to researchers who proposed by May to use AI to carry out similar tasks.[186][187]

In March 2020, the distributed computing project Folding@home launched a program to assist drug developers, initially simulating protein targets from SARS-CoV-2 and the related SARS-CoV virus, which has been studied previously.[188][189][190][191][192][193]

Distributed computing project Rosetta@home also joined the effort in March. The project uses computers of volunteers to model SARS-CoV-2 virus proteins to discover possible drug targets or create new proteins to neutralize the virus. Researchers revealed that with the help of Rosetta@home, they had been able to "accurately predict the atomic-scale structure of an important coronavirus protein weeks before it could be measured in the lab."[194]

In May 2020, the OpenPandemics – COVID-19 partnership between Scripps Research and IBM's World Community Grid was launched. The partnership is a distributed computing project that "will automatically run a simulated experiment in the background [of connected home PCs] which will help predict the effectiveness of a particular chemical compound as a possible treatment for COVID-19".[195]

International Solidarity and Discovery Trials

In March, the World Health Organization (WHO) launched the coordinated "Solidarity Trial" in 10 countries on five continents to rapidly assess in thousands of COVID-19 infected people the potential efficacy of existing antiviral and anti-inflammatory agents not yet evaluated specifically for COVID-19 illness.[2][16] By late April, hospitals in over 100 countries were involved in the trial.[196]

The individual or combined drugs undergoing initial studied are 1) lopinavir–ritonavir combined, 2) lopinavir–ritonavir combined with interferon-beta, 3) remdesivir or 4) (hydroxy)chloroquine in separate trials and hospital sites internationally.[2][16] Following a study published by The Lancet on safety concerns with hydroxychloroquine, the WHO suspended use of it from the Solidarity trial in May 2020,[197][198] reinstated it after the research was retracted,[199] then abandoned further use of the drug for COVID-19 treatment when analysis showed in June that it provided no benefit.[43]

With about 15% of people infected by COVID-19 having severe illness, and hospitals being overwhelmed during the pandemic, WHO recognized a rapid clinical need to test and repurpose these drugs as agents already approved for other diseases and recognized as safe.[2] The Solidarity project is designed to give rapid insights to key clinical questions:[2][200]

- Do any of the drugs reduce mortality?

- Do any of the drugs reduce the time a patient is hospitalized?

- Do the treatments affect the need for people with COVID-19-induced pneumonia to be ventilated or maintained in intensive care?

- Could such drugs be used to minimize the illness of COVID-19 infection in healthcare staff and people at high risk of developing severe illness?

Enrolling people with COVID-19 infection is simplified by using data entries, including informed consent, on a WHO website. After the trial staff determines the drugs available at the hospital, the WHO website randomizes the hospitalized subject to one of the trial drugs or to the hospital standard of care for treating COVID-19. The trial physician records and submits follow-up information about the subject status and treatment, completing data input via the WHO Solidarity website. The design of the Solidarity trial is not double-blind – which is normally the standard in a high-quality clinical trial – but the WHO needed speed with quality for the trial across many hospitals and countries.[2] A global safety monitoring board of WHO physicians examine interim results to assist decisions on safety and effectiveness of the trial drugs, and alter the trial design or recommend an effective therapy.[2][200] A similar web-based study to Solidarity, called "Discovery", was initiated in March across seven countries by INSERM (Paris, France).[2][34]

The Solidarity trial seeks to implement coordination across hundreds of hospital sites in different countries – including those with poorly-developed infrastructure for clinical trials – yet needs to be conducted rapidly. According to John-Arne Røttingen, chief executive of the Research Council of Norway and chairman of the Solidarity trial international steering committee, the trial would be considered effective if therapies are determined to "reduce the proportion of patients that need ventilators by, say, 20%, that could have a huge impact on our national health-care systems."[30]

During March, funding for the Solidarity trial reached US$108 million from 203,000 individuals, organizations and governments, with 45 countries involved in financing or trial management.[197]

A clinical trial design in progress may be modified as an "adaptive design" if accumulating data in the trial provide early insights about positive or negative efficacy of the treatment.[201][202] The global Solidarity and European Discovery trials of hospitalized people with severe COVID-19 infection apply adaptive design to rapidly alter trial parameters as results from the four experimental therapeutic strategies emerge.[11][34][203] Adaptive designs within ongoing Phase II–III clinical trials on candidate therapeutics may shorten trial durations and use fewer subjects, possibly expediting decisions for early termination or success, and coordinating design changes for a specific trial across its international locations.[29][202][204]

Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial

The US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) initiated an adaptive design, international Phase III trial (called "ACTT") to involve up to 800 hospitalized COVID-19 people at 100 sites in multiple countries. Beginning with use of remdesivir as the primary treatment over 29 days, the trial definition of its adaptive protocol states that "there will be interim monitoring to introduce new arms and allow early stopping for futility, efficacy, or safety. If one therapy proves to be efficacious, then this treatment may become the control arm for comparison(s) with new experimental treatment(s)."[38]

Operation Warp Speed

Operation Warp Speed (OWS) was a public–private partnership initiated by the United States government to facilitate and accelerate the development, manufacturing, and distribution of COVID-19 vaccines, therapeutics, and diagnostics.[205][206] The first news report of Operation Warp Speed was on April 29, 2020,[207][208][209] and the program was officially announced on May 15, 2020.[205] It was headed by Moncef Slaoui from May 2020 to January 2021 and by David A. Kessler from January to February 2021.[210] At the end of February 2021, Operation Warp Speed was transferred into the responsibilities of the White House COVID-19 Response Team.[211]

The program promoted mass production of multiple vaccines, and different types of vaccine technologies, based on preliminary evidence. Then there were clinical trials. The plan anticipated that some of these vaccines would not prove safe or effective, making the program more costly than typical vaccine development, but potentially leading to the availability of a viable vaccine several months earlier than typical timelines.[212]

Operation Warp Speed, initially funded with about $10 billion from the CARES Act (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security) passed by the United States Congress on March 27, 2020,[205] was an interagency program that includes components of the Department of Health and Human Services, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Food and Drug Administration, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA); the Department of Defense; private firms; and other federal agencies, including the Department of Agriculture, the Department of Energy, and the Department of Veterans Affairs.[205]RECOVERY Trial

A large-scale, randomized controlled trial named the RECOVERY Trial was set up in March 2020, in the UK to test possible treatments for COVID-19. It is run by the Nuffield Departments of Public Health and of Medicine at the University of Oxford and is testing five repurposed drugs and also convalescent plasma. The trial enrolled more than 11,500 COVID-19 positive participants in the U.K by June 2020.[44][213][214]

During April, the British RECOVERY (Randomised Evaluation of COVid-19 thERapY) trial was launched initially in 132 hospitals across the UK,[215] expanding to become one of the world's largest COVID-19 clinical studies, involving 5400 infected people under treatment at 165 UK hospitals, as of mid-April.[216] The trial is examining different potential therapies for severe COVID-19 infection: lopinavir/ritonavir, low-dose dexamethasone (an anti-inflammatory steroid), hydroxychloroquine, and azithromycin (a common antibiotic).[213] In June, the trial arm using hydroxychloroquine was discontinued when analyses showed it provided no benefit.[44]

On 16 June the trial group released a statement that dexamethasone had been shown to reduce mortality in patients receiving respiratory support.[217] In a controlled trial around 2,000 hospital patients were given dexamethasone and were compared with more than 4,000 who did not receive the drug. For patients on ventilators, it cut the risk of death from 40% to 28% (1 in 8). For patients needing oxygen, it cut the risk of death from 25% to 20% (1 in 5).[218]

By the end of June 2020, the trial had published findings regarding hydroxychloroquine and dexamethasone.[44][219] It had also announced results for lopinavir/ritonavir which were published in October 2020. The lopinavir-ritonavir and hydroxychloroquine arms were closed to new entrants after being shown to be ineffective.[44][220][221] Dexamethasone was closed to new adult entries after positive results and by November 2020, was open to child entries.

PANORAMIC trial

Launched in December 2021, the PANORAMIC trial will test the effectiveness of molnupiravir and nirmatrelvir/ritonavir in preventing hospitalisation and helping faster recovery for people aged over 50 and those at higher risk due to underlying health conditions.[222][223] PANORAMIC is sponsored by the University of Oxford and funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR).[222] As of March 2022 has over 16,000 people enrolled as participants making it the largest study into COVID-19 antivirals.[224]

See also

References

- ^ "COVID-19 vaccine and therapeutics tracker". BioRender. 5 April 2021. Archived from the original on 3 October 2020. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Kupferschmidt K, Cohen J (22 March 2020). "WHO launches global megatrial of the four most promising coronavirus treatments". Science Magazine. doi:10.1126/science.abb8497. S2CID 216325781. Archived from the original on 14 September 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ "First regulatory workshop on COVID-19 facilitates global collaboration on vaccine development". European Medicines Agency. 18 March 2020. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ a b "Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Continues to Facilitate Development of Treatments" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 19 March 2020. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ "China approves first anti-viral drug against coronavirus Covid-19". Clinical Trials Arena. 18 February 2020. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ "Chinese Vaccine Approved for Human Testing at Virus Epicenter". Bloomberg News. 19 March 2020. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ a b c d Dhama K, Sharun K, Tiwari R, Dadar M, Malik YS, Singh KP, et al. (June 2020). "COVID-19, an emerging coronavirus infection: advances and prospects in designing and developing vaccines, immunotherapeutics, and therapeutics". Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics. 16 (6): 1232–1238. doi:10.1080/21645515.2020.1735227. PMC 7103671. PMID 32186952.

- ^ a b Zhang L, Liu Y (May 2020). "Potential interventions for novel coronavirus in China: A systematic review". Journal of Medical Virology. 92 (5): 479–490. doi:10.1002/jmv.25707. PMC 7166986. PMID 32052466.

- ^ a b Fox M (19 March 2020). "Drug makers are racing to develop immune therapies for Covid-19. Will they be ready in time?". Stat. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ Chan M (19 March 2020). "Chinese military scientists ordered to win global race to develop coronavirus vaccine". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- ^ a b c d e COVID-19 Clinical Research Coalition (April 2020). "Global coalition to accelerate COVID-19 clinical research in resource-limited settings". Lancet. 395 (10233): 1322–1325. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30798-4. PMC 7270833. PMID 32247324.

- ^ a b c Maguire BJ, Guérin PJ (2 April 2020). "A living systematic review protocol for COVID-19 clinical trial registrations". Wellcome Open Research. 5: 60. doi:10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15821.1. PMC 7141164. PMID 32292826.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Li G, De Clercq E (March 2020). "Therapeutic options for the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 19 (3): 149–150. doi:10.1038/d41573-020-00016-0. PMID 32127666.

- ^ Dong L, Hu S, Gao J (29 February 2020). "Discovering drugs to treat coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Drug Discoveries & Therapeutics. 14 (1): 58–60. doi:10.5582/ddt.2020.01012. PMID 32147628. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ a b c d Harrison C (April 2020). "Coronavirus puts drug repurposing on the fast track". Nature Biotechnology. 38 (4): 379–381. doi:10.1038/d41587-020-00003-1. PMID 32205870. S2CID 213394680.

- ^ a b c Cheng MP, Lee TC, Tan DH, Murthy S (April 2020). "Generating randomized trial evidence to optimize treatment in the COVID-19 pandemic". CMAJ. 192 (15): E405–E407. doi:10.1503/cmaj.200438. PMC 7162442. PMID 32336678.

- ^ a b c d e "The Drug Development Process". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 4 January 2018. Archived from the original on 22 February 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ "Call to pool research resources into large multi-centre, multi-arm clinical trials to generate sound evidence on COVID-19 treatments". European Medicines Agency. 19 March 2020. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u "COVID-19 vaccine and treatments tracker (Choose vaccines or treatments tab, apply filters to view select data)". Milken Institute. 21 June 2021. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b c Strovel J, Sittampalam S, Coussens NP, Hughes M, Inglese J, Kurtz A, et al. (1 July 2016). "Early Drug Discovery and Development Guidelines: For Academic Researchers, Collaborators, and Start-up Companies". Assay Guidance Manual. Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. PMID 22553881. Archived from the original on 19 April 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ a b Taylor D (2015). "The Pharmaceutical Industry and the Future of Drug Development". Issues in Environmental Science and Technology. Royal Society of Chemistry: 1–33. doi:10.1039/9781782622345-00001. ISBN 978-1-78262-189-8.

- ^ "Step 2: Preclinical Research". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 4 January 2018. Archived from the original on 16 September 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ Grenfell R, Drew T (14 February 2020). "Here's why the WHO says a coronavirus vaccine is 18 months away". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 5 December 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ Preston E (19 March 2020). "Why will a coronavirus vaccine take so long?". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ Gates B (February 2020). "Responding to Covid-19 – A Once-in-a-Century Pandemic?". The New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (18): 1677–1679. doi:10.1056/nejmp2003762. PMID 32109012.

- ^ a b c "Clinical development success rates: 2006–2015" (PDF). BIO Industry Analysis. June 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ a b "The drug development process: Clinical research". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 4 January 2018. Archived from the original on 20 June 2020. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ DiMasi JA, Grabowski HG, Hansen RW (May 2016). "Innovation in the pharmaceutical industry: New estimates of R&D costs". Journal of Health Economics. 47: 20–33. doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2016.01.012. hdl:10161/12742. PMID 26928437. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 May 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- ^ a b c Van Norman GA (June 2019). "Phase II Trials in Drug Development and Adaptive Trial Design". JACC. Basic to Translational Science. 4 (3): 428–437. doi:10.1016/j.jacbts.2019.02.005. PMC 6609997. PMID 31312766.

- ^ a b Mullard A (April 2020). "Flooded by the torrent: the COVID-19 drug pipeline". Lancet. 395 (10232): 1245–1246. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30894-1. PMC 7162641. PMID 32305088.

- ^ a b Thorlund K, Dron L, Park J, Hsu G, Forrest JI, Mills EJ (June 2020). "A real-time dashboard of clinical trials for COVID-19". The Lancet. Digital Health. 2 (6): e286–e287. doi:10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30086-8. PMC 7195288. PMID 32363333.

- ^ a b "What are the phases of clinical trials?". American Cancer Society. 2020. Archived from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ "Remdesivir approval status". Drugs.com. 24 March 2020. Archived from the original on 19 September 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "Launch of a European clinical trial against COVID-19". INSERM. 22 March 2020. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

The great strength of this trial is its "adaptive" nature. This means that ineffective experimental treatments can very quickly be dropped and replaced by other molecules that emerge from research efforts. We will therefore be able to make changes in real time, in line with the most recent scientific data, in order to find the best treatment for our patients

- ^ Pagliarulo N (5 March 2020). "A closer look at the Ebola drug that's become the top hope for a coronavirus treatment". BioPharma Dive. Archived from the original on 31 October 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

There's only one drug right now that we think may have real efficacy. And that's remdesivir." said Bruce Aylward, a senior advisor and international leader of the World Health Organization's joint mission to China

- ^ "Emergency access to remdesivir outside of clinical trials". Gilead Sciences. 1 April 2020. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ a b "Information for clinicians on therapeutic options for COVID-19 patients". US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 21 March 2020. Archived from the original on 8 April 2020. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- ^ a b Clinical trial number NCT04280705 for "Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial (ACTT)" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ^ "NIH clinical trial shows remdesivir accelerates recovery from advanced COVID-19" (Press release). US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. 29 April 2020. Archived from the original on 30 April 2020. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ Wang Y, Zhang D, Du G, Du R, Zhao J, Jin Y, et al. (May 2020). "Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID-19: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial". Lancet. 395 (10236): 1569–1578. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31022-9. PMC 7190303. PMID 32423584.

- ^ a b "Hydroxychloroquine sulfate". Drugs.com. 31 March 2020. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ a b "Chloroquine phosphate". Drugs.com. 31 March 2020. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ a b Mulier T (17 June 2020). "Hydroxychloroquine halted in WHO-sponsored COVID-19 trials". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 11 October 2020. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "No clinical benefit from use of hydroxychloroquine in hospitalised patients with COVID-19". Recovery Trial, Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford, UK. 5 June 2020. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ "Fujifilm Announces the Start of a Phase III Clinical Trial of Influenza Antiviral Drug Avigan (favipiravir) on COVID-19 in Japan and Commits to Increasing Production". Drugs.com via Fujifilm Toyama Chemical Co., Ltd. 31 March 2020. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ^ Gregory A (18 March 2020). "Coronavirus: Japanese anti-viral drug effective in treating patients, Chinese official says". The Independent. Archived from the original on 9 October 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ^ a b "Ritonavir". Drugs.com. 2020. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ^ "Kevzara". Drugs.com. 7 March 2019. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ^ Staines R (31 March 2020). "Sanofi begins trial of Kevzara against COVID-19 complications". PharmaPhorum. Archived from the original on 17 August 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ^ McGrath J (2 April 2020). "All the COVID-19 vaccines and treatments currently in clinical trials". Digital Trends. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ^ "Tocilizumab". Drugs.com. 7 June 2019. Archived from the original on 8 September 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ^ Slater H (26 March 2020). "FDA approves Phase III clinical trial of tocilizumab for COVID-19 pneumonia". Cancer Network, MJH Life Sciences. Archived from the original on 17 June 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ^ "Roche provides an update on the phase III COVACTA trial of Actemra/RoActemra in hospitalised patients with severe COVID-19 associated pneumonia". Hoffmann-La Roche. 29 July 2020. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ Clinical trial number NCT04351152 for "Phase 3 Study to Evaluate Efficacy and Safety of Lenzilumab in Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19 Pneumonia" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ^ "Dapagliflozin: MedlinePlus Drug Information". medlineplus.gov. 20 April 2020. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ Clinical trial number NCT04350593 for "Dapagliflozin in Respiratory Failure in Patients With COVID-19 (DARE-19)" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ^ Clinical trial number NCT04317040 for "CD24Fc as a Non-antiviral Immunomodulator in COVID-19 Treatment (SAC-COVID)" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ^ "An Open-Label Study of Apabetalone in Covid Infection". NIH National Library of Medicine. 20 May 2021. Archived from the original on 24 May 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ "Repurposing drugs". National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS). 7 November 2017. Archived from the original on 4 October 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ a b c Kruse RL (31 January 2020). "Therapeutic strategies in an outbreak scenario to treat the novel coronavirus originating in Wuhan, China". F1000Research. 9: 72. doi:10.12688/f1000research.22211.1. PMC 7029759. PMID 32117569.

- ^ Mitjà O, Clotet B (March 2020). "Use of antiviral drugs to reduce COVID-19 transmission". The Lancet. Global Health. 8 (5). Elsevier BV: e639–e640. doi:10.1016/s2214-109x(20)30114-5. PMC 7104000. PMID 32199468.

- ^ "UN health chief announces global 'solidarity trial' to jumpstart search for COVID-19 treatment". United Nations – News. World Health Organization. 18 March 2020. Archived from the original on 23 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ Kupferschmidt K, Cohen J (March 2020). "Race to find COVID-19 treatments accelerates". Science. 367 (6485): 1412–1413. Bibcode:2020Sci...367.1412K. doi:10.1126/science.367.6485.1412. PMID 32217705.

- ^ "COVID-19 drug development: Landscape analysis of therapeutics (table)" (PDF). United Nations, World Health Organization. 21 March 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ a b c d Piechotta V, Iannizzi C, Chai KL, Valk SJ, Kimber C, Dorando E, et al. (20 May 2021). "Convalescent plasma or hyperimmune immunoglobulin for people with COVID-19: a living systematic review". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021 (5): CD013600. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013600.pub4. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 8135693. PMID 34013969.

- ^ "FDA now allows treatment of life-threatening COVID-19 cases using blood from patients who have recovered". TechCrunch. 24 March 2020. Archived from the original on 11 October 2020. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ a b Fioravanti C (14 December 2020). "Butantan desenvolve soro contra coronavírus" [Butantan develops serum against coronavirus]. Revista Pesquisa Fapesp (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ Monnerat A (4 January 2021). "Vital Brazil desenvolve soro contra covid-19, mas medicamento ainda não foi testado em humanos" [Vital Brazil develops serum against COVID-19, but drug has yet to be tested in humans]. O Estado de S. Paulo (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 17 January 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ "Argentina aprueba uso de suero equino que reduce en un 45% las muertes por COVID-19" [Argentina approves use of equine serum which reduces COVID-19 deaths by 45%] (in Spanish). Deutsche Welle. 11 January 2021. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ a b "Coronavirus: terapistas rechazaron "fuertemente" el uso de suero equino en pacientes graves" [Coronavirus: medics "strongly" reject use of equine serum in severe patients]. Clarín (in Spanish). 17 January 2021. Archived from the original on 17 January 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ "FDA Authorizes Monoclonal Antibodies for Treatment of COVID-19". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 10 February 2021. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Lilly's bamlanivimab (LY-CoV555) administered with etesevimab (LY-CoV016) receives FDA emergency use authorization for COVID-19" (Press release). Eli Lilly and Company. 9 February 2021. Retrieved 9 February 2021 – via PR Newswire.

- ^ "New data show treatment with Lilly's neutralizing antibodies bamlanivimab (LY-CoV555) and etesevimab (LY-CoV016) together reduced risk of COVID-19 hospitalizations and death by 70 percent" (Press release). Eli Lilly and Company. 26 January 2021. Retrieved 9 February 2021 – via PR Newswire.

- ^ Hurt AC, Wheatley AK (April 2021). "Neutralizing Antibody Therapeutics for COVID-19". Viruses. 13 (4): 628. doi:10.3390/v13040628. PMC 8067572. PMID 33916927.

- ^ "etesevimab". IUPHAR/BPS Guide to Pharmacology. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "Lilly announces agreement with U.S. government to supply 300,000 vials of investigational neutralizing antibody bamlanivimab (LY-CoV555) in an effort to fight COVID-19". Eli Lilly and Company (Press release). 28 October 2020.

- ^ a b "FDA authorizes bamlanivimab and etesevimab for COVID-19". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ a b "Emergency Use Authorization 094" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 16 September 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b "Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Limits Use of Certain Monoclonal Antibodies to Treat COVID-19 Due to the Omicron Variant" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 24 January 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c "FDA Authorizes New Monoclonal Antibody for Treatment of COVID-19 that Retains Activity Against Omicron Variant" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 11 February 2022. Archived from the original on 12 February 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Lilly's bebtelovimab receives Emergency Use Authorization for the treatment of mild-to-moderate COVID-19" (Press release). Eli Lilly and Company. 11 February 2022. Archived from the original on 11 February 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2022 – via PR Newswire.

- ^ "AbCellera-Discovered Antibody, Bebtelovimab, Receives U.S. FDA Emergency Use Authorization for the Treatment of Mild-to-Moderate COVID-19" (Press release). AbCellera. 11 February 2022. Archived from the original on 11 February 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ Suran M (March 2022). "Federal Government Buys Thousands of Bebtelovimab Doses". JAMA. 327 (12): 1117. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.3520. PMID 35315904. S2CID 247599102.

- ^ "Bebtelovimab (Code C182122)". National Cancer Institute. Archived from the original on 13 February 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "FDA Announces Bebtelovimab is Not Currently Authorized in the US". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 30 November 2022. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b "Casirivimab injection, solution, concentrate Imdevimab injection, solution, concentrate REGEN-COV – casirivimab and imdevimab kit". DailyMed. Archived from the original on 4 January 2021. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "Ronapreve EPAR". European Medicines Agency. 10 November 2021. Archived from the original on 13 November 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2021. Text was copied from this source which is copyright European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- ^ a b "Fact Sheet For Health Care Providers Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) Of Casirivimab And Imdevimab" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). June 2021. Archived from the original on 2 November 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ Baum A, Fulton BO, Wloga E, Copin R, Pascal KE, Russo V, et al. (August 2020). "Antibody cocktail to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein prevents rapid mutational escape seen with individual antibodies". Science. 369 (6506): 1014–1018. Bibcode:2020Sci...369.1014B. doi:10.1126/science.abd0831. PMC 7299283. PMID 32540904.

- ^ Kelland K (14 September 2020). "Regeneron's antibody drug added to UK Recovery trial of COVID treatments". Reuters. Archived from the original on 11 January 2021. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ "Regeneron's COVID-19 Response Efforts". Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs (ASPA) (7 January 2021). "Monoclonal Antibodies for High-Risk COVID-19 Positive Patients". combatCOVID.hhs.gov. Archived from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ^ "Ronapreve". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 18 October 2021. Archived from the original on 23 October 2021. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ^ "Summary of Product Characteristics for Ronapreve". Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). 20 August 2021. Archived from the original on 30 August 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ^ "Japan becomes first country to approve Ronapreve (casirivimab and imdevimab) for the treatment of mild to moderate COVID-19". Roche (Press release). 20 July 2021. Archived from the original on 24 July 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ^ "Regulatory approval of Ronapreve". Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). 20 August 2021. Archived from the original on 30 August 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ^ "First monoclonal antibody treatment for COVID-19 approved for use in the UK" (Press release). Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). 20 August 2021. Archived from the original on 30 August 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ^ "Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Limits Use of Certain Monoclonal Antibodies to Treat COVID-19 Due to the Omicron Variant" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 24 January 2022. Archived from the original on 26 January 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b "FDA Roundup: March 22, 2024". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 22 March 2024. Archived from the original on 23 March 2024. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Highlight of Emergency Use Authorization: Pemgarda (pemivibart)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 23 March 2024. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- ^ a b "Invivyd Announces FDA Authorization for Emergency Use of Pemgarda (Formerly VYD222) for Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) of COVID-19" (Press release). Invivyd. 22 March 2024. Archived from the original on 23 March 2024. Retrieved 23 March 2024 – via GlobeNewswire.

- ^ a b c d "Regkirona EPAR". European Medicines Agency. 10 November 2021. Archived from the original on 12 November 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2021. Text was copied from this source which is copyright European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- ^ "Celltrion Develops Tailored Neutralising Antibody Cocktail Treatment with CT-P59 to Tackle COVID-19 Variant Spread Using Its Antibody Development Platform" (Press release). Celltrion. 11 February 2021. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2021 – via Business Wire.

- ^ "Celltrion Group announces positive top-line efficacy and safety data from global Phase II/III clinical trial of COVID-19 treatment candidate CT-P59" (Press release). Celltrion. 13 January 2021. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2021 – via Business Wire.

- ^ "EMA issues advice on use of regdanvimab for treating COVID-19". European Medicines Agency. 26 March 2021. Archived from the original on 15 November 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ "Regkirona". Union Register of medicinal products. 12 November 2021. Archived from the original on 24 April 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ a b "Xevudy EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 15 December 2021. Archived from the original on 18 December 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021. Text was copied from this source which is copyright European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- ^ a b c "EMA starts rolling review of sotrovimab (VIR-7831) for COVID-19". European Medicines Agency (EMA) (Press release). 7 May 2021. Archived from the original on 3 August 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2021. Text was copied from this source which is copyright European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- ^ a b "EMA issues advice on use of sotrovimab (VIR-7831) for treating COVID-19". European Medicines Agency (EMA) (Press release). 21 May 2021. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2021. Text was copied from this source which is copyright European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- ^ "GSK and Vir Biotechnology announce the start of the EMA rolling review of VIR-7831 (sotrovimab) for the early treatment of COVID-19". GlaxoSmithKline (Press release). 7 May 2021. Archived from the original on 22 May 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ "EMA starts review of VIR-7831 for treating patients with COVID-19". European Medicines Agency (EMA) (Press release). 15 April 2021. Archived from the original on 22 May 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ "FDA Roundup: April 5, 2022". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (Press release). 5 April 2022. Archived from the original on 8 April 2022. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Cilgavimab". IUPHAR/BPS Guide to Pharmacology. IUPHAR. 27 December 2021. Archived from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ "Tixagevimab". IUPHAR/BPS Guide to Pharmacology. IUPHAR. 27 December 2021. Archived from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ Abramowicz M, Zuccotti G, Pflomm JM, eds. (January 2022). "Tixagevimab and Cilgavimab (Evusheld) for Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis of COVID-19". JAMA. 327 (4): 384–385. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.24931. PMID 35076671.

- ^ Ray S (21 August 2021). "AstraZeneca's Covid-19 Antibody Therapy Effective In Preventing Symptoms Among High-Risk Groups, Trial Finds". Forbes. ISSN 0015-6914. Archived from the original on 21 August 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ Goriainoff AO (20 August 2021). "AstraZeneca Says AZD7442 Antibody Phase 3 Trial Met Primary Endpoint in Preventing Covid-19". MarketWatch. Archived from the original on 21 August 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ "Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Authorizes New Long-Acting Monoclonal Antibodies for Pre-exposure Prevention of COVID-19 in Certain Individuals". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 8 December 2021. Archived from the original on 28 April 2022. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c "FDA authorizes Gohibic (vilobelimab) injection for the treatment of COVID-19". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 4 April 2023. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b https://www.fda.gov/media/166824/download

- ^ a b https://www.fda.gov/media/166823/download

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ https://www.fda.gov/media/166826/download

- ^ "InflaRx Receives FDA Emergency Use Authorization for Gohibic (vilobelimab) for Treatment of Critically Ill COVID-19 Patients" (Press release). InflaRx N.V. 4 April 2023. Retrieved 4 April 2023 – via GlobeNewswire.

- ^ a b c d "Summary of Product Characteristics for Lagevrio". Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). 4 November 2021. Archived from the original on 4 November 2021. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ Toots M, Yoon JJ, Cox RM, Hart M, Sticher ZM, Makhsous N, et al. (October 2019). "Characterization of orally efficacious influenza drug with high resistance barrier in ferrets and human airway epithelia". Science Translational Medicine. 11 (515): eaax5866. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aax5866. PMC 6848974. PMID 31645453.

- ^ Toots M, Yoon JJ, Hart M, Natchus MG, Painter GR, Plemper RK (April 2020). "Quantitative efficacy paradigms of the influenza clinical drug candidate EIDD-2801 in the ferret model". Translational Research. 218: 16–28. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2019.12.002. PMC 7568909. PMID 31945316.

- ^ Cohen B, Piller C (May 2020). "Emails offer look into whistleblower charges of cronyism behind potential COVID-19 drug". Science. doi:10.1126/science.abc7055.

- ^ Cully M (January 2022). "A tale of two antiviral targets - and the COVID-19 drugs that bind them". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 21 (1): 3–5. doi:10.1038/d41573-021-00202-8. PMID 34857884. S2CID 244851870.

- ^ Aleccia J (29 September 2021). "Daily pill to treat COVID could be just months away". ABC News. Kaiser Health News. Archived from the original on 29 September 2021. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- ^ Jayk Bernal A, Gomes da Silva MM, Musungaie DB, Kovalchuk E, Gonzalez A, Delos Reyes V, et al. (December 2021). "Molnupiravir for oral treatment of COVID-19 in nonhospitalized patients". The New England Journal of Medicine. 386 (6): 509–520. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2116044. PMC 8693688. PMID 34914868.

- ^ Singh AK, Singh A, Singh R, Misra A (November 2021). "Molnupiravir in COVID-19: A systematic review of literature". Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome. 15 (6): 102329. doi:10.1016/j.dsx.2021.102329. PMC 8556684. PMID 34742052.

- ^ "First oral antiviral for COVID-19, Lagevrio (molnupiravir), approved by MHRA" (Press release). Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). 4 November 2021. Archived from the original on 5 January 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ "Merck and Ridgeback's Molnupiravir, an Oral COVID-19 Antiviral Medicine, Receives First Authorization in the World". Merck & Co. (Press release). 4 November 2021. Archived from the original on 4 November 2021. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ Robbins R, Khan AJ, Specia M (4 November 2021). "Britain Becomes First to Authorize an Antiviral Pill for Covid-19". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 November 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- ^ "Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Authorizes Additional Oral Antiviral for Treatment of COVID-19 in Certain Adults". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 23 December 2021. Archived from the original on 23 December 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Kimball S (30 November 2021). "FDA advisory panel narrowly endorses Merck's oral Covid treatment pill, despite reduced efficacy and safety questions". CNBC. Archived from the original on 1 January 2022. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ Lin MZ (24 December 2021). "A new drug to treat covid could create a breeding ground for mutant viruses". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 30 December 2021. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ Service RF (November 2021). "A prominent virologist warns COVID-19 pill could unleash dangerous mutants. Others see little cause for alarm". Science. doi:10.1126/science.acx9591.

- ^ Sanderson T, Hisner R, Donovan-Banfield I, Hartman H, Løchen A, Peacock TP, et al. (September 2023). "A molnupiravir-associated mutational signature in global SARS-CoV-2 genomes". Nature. 623 (7987): 594–600. Bibcode:2023Natur.623..594S. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06649-6. PMC 10651478. PMID 37748513. S2CID 262748823.

- ^ McCarthy MW (December 2022). "Ensitrelvir as a potential treatment for COVID-19". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 23 (18): 1995–1998. doi:10.1080/14656566.2022.2146493. PMID 36350029. S2CID 253418404.

- ^ Fujikawa M (22 November 2022). "Japan Approves First Homegrown Covid-19 Antiviral Pill". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ "Shionogi's Covid antiviral lands first approval in Japan's new emergency approval pathway". Endpoints News. 22 November 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ "Xocova: Powerful New Japanese Pill for Coronavirus Treatment". BioPharma Media. February 2022.

- ^ Unoh Y, Uehara S, Nakahara K, Nobori H, Yamatsu Y, Yamamoto S, et al. (May 2022). "Discovery of S-217622, a Noncovalent Oral SARS-CoV-2 3CL Protease Inhibitor Clinical Candidate for Treating COVID-19". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 65 (9): 6499–6512. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c00117. PMC 8982737. PMID 35352927.

- ^ "Shionogi presents positive Ph II/III results for COVID-19 antiviral S-217622". thepharmaletter.com. 31 January 2022.

- ^ a b "Xocova (Ensitrelvir Fumaric Acid) Tablets 125mg Approved in Japan for the Treatment of SARS-CoV-2 Infection, under the Emergency Regulatory Approval System". Shionogi (Press release). 22 November 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ "Shionogi's new COVID pill appears to ease omicron symptoms". Nikkei Asia. 21 December 2021.

- ^ Uraki R, Kiso M, Iida S, Imai M, Takashita E, Kuroda M, et al. (IASO study team) (May 2022). "Characterization and antiviral susceptibility of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron/BA.2". Nature. 607 (7917): 119–127. Bibcode:2022Natur.607..119U. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04856-1. PMC 10579982. PMID 35576972. S2CID 248833104.

- ^ Amani B, Amani B (February 2023). "Efficacy and safety of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid) for COVID-19: A rapid review and meta-analysis". Journal of Medical Virology. 95 (2): e28441. doi:10.1002/jmv.28441. PMC 9880713. PMID 36576379.

- ^ "Paxlovid". COVID-19 vaccines and treatments portal. 17 January 2022. Archived from the original on 22 April 2022. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ New Drug Therapy Approvals 2023 (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Report). January 2024. Archived from the original on 10 January 2024. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2022". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 30 August 2024. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "Nirmatrelvir; Ritonavir Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013 - 2022". ClinCalc. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ Markowski MC, Tutrone R, Pieczonka C, Barnette KG, Getzenberg RH, Rodriguez D, et al. (July 2022). "A Phase Ib/II Study of Sabizabulin, a Novel Oral Cytoskeleton Disruptor, in Men with Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer with Progression on an Androgen Receptor-targeting Agent". Clinical Cancer Research. 28 (13): 2789–2795. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-22-0162. PMC 9774054. PMID 35416959. S2CID 248128050.

- ^ rme (13 April 2022). "COVID-19: Krebsmittel Sabizabulin halbiert Sterberate bei schweren Erkrankungen" [COVID-19: Cancer drug Sabizabulin halves death rate in severe cases]. aerzteblatt.de. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- ^ "Sabizabulin - Veru Healthcare". AdisInsight. Springer Nature Switzerland AG.

- ^ Mahmud F, Deng S, Chen H, Miller DD, Li W (December 2020). "Orally available tubulin inhibitor VERU-111 enhances antitumor efficacy in paclitaxel-resistant lung cancer". Cancer Letters. 495: 76–88. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2020.09.004. PMC 7669640. PMID 32920198.

- ^ Li CM, Lu Y, Chen J, Costello TA, Narayanan R, Dalton MN, et al. (November 2012). "Orally bioavailable tubulin antagonists for paclitaxel-refractory cancer". Pharmaceutical Research. 29 (11): 3053–3063. doi:10.1007/s11095-012-0814-5. PMC 3646298. PMID 22760659.

- ^ "About the Innovative Medicines Initiative". European Innovative Medicines Initiative. 2020. Archived from the original on 2 September 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2020.