Canadian Football League in the United States

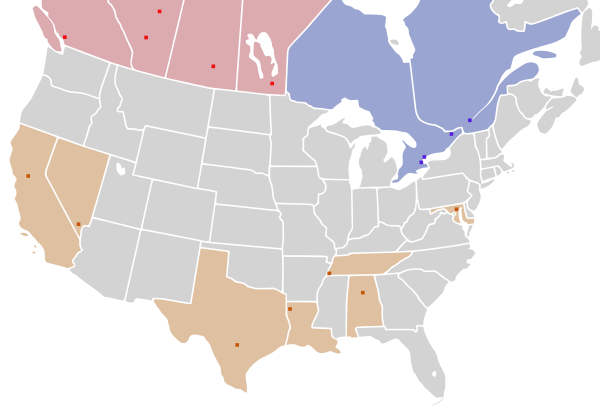

The Canadian Football League (CFL), which features teams based in Canada, has made efforts to gain further audience in the United States, most directly through expansion into the country from the 1993 CFL season through the 1995 CFL season. The CFL plays Canadian football, a form of gridiron football which is somewhat different from the more common American football played in the United States and other parts of the world.

The first American team, the Sacramento Gold Miners, joined in 1993. The league added three more American teams in 1994, after which two more teams joined, one re-located and one folded to bring the total to five in 1995. In the latter year, the teams were aligned into a new South Division. The three years saw numerous ownership debacles on both sides of the U.S.–Canada border. The Baltimore Stallions became the only American-based team to win the Grey Cup championship, in 1995.

With the exception of Baltimore, all of the American teams consistently lost money. Tension also arose between the American and Canadian contingents over rule changes, scheduling, import rules, and marketing. Facing these difficulties, the league returned to being exclusively Canadian beginning with the 1996 season.

While expansion was the most notable CFL effort in the United States, the league had also made previous inroads. Eleven neutral-site CFL games (including exhibition games) have been held in the United States. In earlier decades when the CFL season started much later than it does today (i.e. around the same time as that of the National Football League), NFL teams were occasionally invited northward for exhibition interleague play.

The CFL has also attempted to find a television audience in the United States, with one notable venture coinciding with the NFL players' strike in 1982, and more recently on ESPN. While the CFL's presence on U.S. television has consistently been limited to cable TV networks and streaming services, its U.S. TV audience was enough to account for about 20% of the league's total North American viewership during the 2018 season.

Pre-expansion era

[edit]Until 1993, the Canadian Football League, and its predecessor associations, had always operated solely within Canada, despite most other professional sports leagues in North America being cross-border enterprises. The substantially different rules and fields of the Canadian and American games and the popularity of the National Football League and NCAA Division I-A football in the United States were generally seen to inhibit the chances of any sort of expansion into the United States. Lackluster CFL television ratings in the United States during the 1982 NFL strike seemed to bolster this argument. A proposal by Bill Tatham to have his Arizona Outlaws and possibly other teams of the moribund United States Football League enter the CFL after the league suspended operations saw little interest in both leagues.[1]

Interleague games

[edit]There had been an ongoing degree of cross-fertilization between Canadian and American leagues for several decades prior to the merger of the Interprovincial Rugby Football Union and the Western Interprovincial Football Union to form the CFL in 1958. Until well into the second half of the twentieth century, football in both countries was often played in facilities designed for baseball, the most popular summer sport in both countries, with both Major League Baseball (whose facilities hosted several NFL teams) and minor league baseball attracting large crowds in both countries. As a result, much like their American counterparts, the Canadian leagues played mainly in the autumn after the baseball season had wound down.

Until the early 1960s, such arrangements allowed for a number of CFL–NFL interleague games to be held in Canada. NFL teams handily won most of these contests, however the most compelling reason they were discontinued was that minor league baseball attendance in both countries fell drastically in the 1950s and 1960s, a development which coincided with MLB telecasts reaching an ever-larger audience. This allowed CFL teams to take over several facilities originally designed to accommodate baseball for their exclusive use, and in turn allowed the CFL to play a less compressed schedule that eventually started in early summer. The NFL, by contrast, had neither the need nor the inclination to play throughout the summer in the much warmer U.S. climate, and thus continued to start its schedule in early September, thus making interleague play with the CFL unfeasible.

Neutral site games

[edit]Eleven neutral-site IRFU/WIFU/CFL games have been played on American soil. The earliest of these dates to 1909, while the bulk occurred between 1951 and 1967. The 1909 game, featuring the Ottawa Rough Riders and Hamilton Tigers of the IRFU, was sponsored by the New York Herald and played at Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx;[2] this in the era when the Canadian game was more similar to rugby football and did not feature modern rules such as the forward pass like the American game.

The next game, a 1951 match-up between the IRFU's Hamilton Tiger-Cats and Toronto Argonauts in Buffalo, was billed as the first true all-Canadian game played in the United States. Played in a city that at the time was embittered with the National Football League after its All-America Football Conference team was controversially excluded from a merger with the NFL, the Buffalo game drew more than 18,000 fans – a decent crowd for the era.[3] In 1958, the first season officially played under the CFL moniker, Hamilton defeated Ottawa in a regular-season contest in front of about 15,000 in Philadelphia's cavernous Municipal Stadium, 24–18. It remains the only CFL game played outside Canada, involving two Canadian teams, that actually counted in the standings.

Prior to and even after the formation of the CFL, the teams of the IRFU (which eventually became the CFL's Eastern Football Conference) were regarded, especially in Eastern Canada, as superior to the Western Canadian teams. Starting in the 1930s, Western Canadian teams had begun aggressively scouting for and recruiting players from the rich American talent pool, largely in an effort to achieve parity with the East. The American Pacific Northwest became a frequent site for WIFU and later CFL preseason games in the 1950s and 1960s with Western Canadian teams, particularly the BC Lions, being called upon to entertain their regional neighbours. News reports from the time suggest a hybrid game of three down Canadian ball played on the more restricted 100 yard American field.[4] One BC–Winnipeg matchup in 1960 was held not on the west coast but in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, presumably because both teams had a number of former University of Iowa stars, including Willie Mitchell, who scored the Lions' only touchdown in a 13–7 loss in front of 12,583. Western teams were mostly ignored by U.S. clubs as potential opposition for preseason interleague contests, although this was in part due to the more onerous travel requirements to Western Canada in an era when rail travel was the norm and the fact the WIFU moved up the start of its regular season long before the Eastern section followed suit. It would not be until 2019 that NFL teams would play any sort of contest in Western Canada.

Most exhibition games involving Canadian teams in the U.S. tended to be characterized by low scores and frequent punting, with crowds between 10,000 and 20,000; these numbers dropped off in the last two games of the era. A low-scoring BC–Edmonton game in Everett, Washington, in 1967 drew just over 6,000;[5] there would not be another CFL game in the United States until the cusp of US expansion itself in 1992.

Television

[edit]The idea of attracting American fans through television has long been a goal of the CFL although the results have been intermittent. As early as 1954, the Interprovincial Rugby Football Union (forerunner of the CFL's East Division) struck a deal with NBC that lasted a year and featured 13 games. The infamous Fog Bowl of 1962 was—at least until play was suspended—broadcast by ABC. Over subsequent years various non-major networks picked up an assortment of games.[25]

The fledgling ESPN cable network signed a deal in 1980 to broadcast 30 CFL regular season games and the playoffs (including the Grey Cup game) in the United States, and CFL games became a fixture of the early years of the network. Two years later, in 1982, after NFL players went on strike in September, the CFL got another chance at major network exposure when NBC bought out the ESPN rights for $100,000 a game to make up for its lost football programming. NBC would air CFL games on Sunday afternoons with full NFL production values and announcing crews. However, every one of the four games shown was a blowout, and the league and network decided to black out the games on the NBC stations closest to the Canadian border, and ratings were a major disappointment. NBC quickly backed out of the arrangement.[25][26]

Expansion

[edit]Background

[edit]The idea of expansion into the United States began to take shape in the early 1990s, prompted by precarious ownership situations and chronic money shortages among the existing Canadian teams. The chief catalyst of the league's struggles was Carling O'Keefe's decision to stop its lucrative television sponsorship in 1987. The arrangement had provided steady income to all of the league's teams, reaching $11 million per season before its withdrawal. However, these guaranteed revenues, instead of being used to grow the league, had subsidized outdated and shoddy financial practices and marketing both at the team and league level. Longtime CFL commissioner Jake Gaudaur, who had negotiated the league's sponsorship deals with Carling, had retired in 1984. The Montreal Alouettes, already having been rescued from failure five years prior, folded during the 1987 preseason.[27] It would take two decades for economic equilibrium to again be reestablished.[28]

With the exception of the Edmonton Eskimos, every team in the league had faced some kind of crisis in the years leading up to 1993. In addition to Montreal's sudden collapse, the Calgary Stampeders and publicly owned Saskatchewan Roughriders had to mount public campaigns to survive.[28] By 1993, the BC Lions had experienced years of ownership chaos and the Winnipeg Blue Bombers faced $3 million in debt, despite frugal management.[28] The Toronto Argonauts were embroiled in a series of ownership crises after the initially successful ownership triumvirate of Bruce McNall, Wayne Gretzky, and John Candy faced mounting financial losses.[29][30] The Hamilton Tiger-Cats were confronting an attendance swoon, fan malaise, and struggling community ownership. Both Southern Ontario teams faced competition at the gate and for general attention from the NFL's Buffalo Bills, then in the middle of their run of four consecutive Super Bowl appearances.[31] Finally, the Ottawa Rough Riders and their fans were being treated to disappointing squads on the field and constant drama off the field from the team's under-capitalized and mercurial owner, Bernie Glieberman.[32]

Against this economic backdrop, a new generation of venture capitalist owners took the place of the community groups, local consortiums, or philanthropists that typically had owned the teams and operated them without any serious profit motive. They were led by McNall in Toronto, Glieberman in Ottawa, and Larry Ryckman in Calgary. Larry Smith was hired as league commissioner in February 1992, reportedly on the explicit understanding that he would pursue American expansion. While Smith would become the most visible face of the era, he emphasized that it was the owners who drove the initiative, particularly McNall and Ryckman.[33] McNall's issues with cash flow, later revealed to be the result of his wealth being inflated by illegal accounting,[34] were one obvious instigator.[35] While the newer owners championed expansion, equal distribution of the expansion fees also appealed to the community owned teams as these would shore up their finances.[36]

1992–1993

[edit]With the green light from the owners, Smith began the task of expanding the league across the border, beginning with a June 1992 exhibition game between the Argonauts and Stampeders in Portland, Oregon. A total of 15,362 attended,[22] close to the averages later American teams would post. Portland was seriously considered for a franchise, but investors failed to emerge.[37] The expansion announcement prompted numerous applications from a wide variety of American cities. By the end of the expansion era, a minimum of 22 cities were reported to have been considered for teams.[38]

Coincidentally, the World League of American Football, an attempt by the NFL to create a spring league in major markets without NFL teams (including Montreal), suspended its North American operations after its 1992 season. WLAF owners Fred Anderson of the Sacramento Surge and Larry J. Benson of the San Antonio Riders applied to join the CFL as the Sacramento Gold Miners and San Antonio Texans, respectively.[37] On January 13, 1993, the league approved both franchises by a vote of 7–1, with Winnipeg dissenting. League owners also decided not to apply the requirement of 20 "non-import" Canadian-raised players to the American squads after being advised that such a requirement would be a violation of US employment laws.[39]

The experiment started on a sour note, however, when an ownership dispute forced Benson to pull San Antonio out on the same evening the franchise was to be formally introduced.[37] Anderson decided to continue with the venture after Benson's withdrawal, but made clear that he did not want his team to be the only American franchise after 1993. The Gold Miners were placed in the very strong West Division and finished last with a record of 6–12.[40] The Gold Miners played at the austere Hornet Stadium, located on the campus of Sacramento State University and averaged around 17,000 fans per game (down slightly from the roughly 21,000 fans per game the Surge had drawn in 1992), selling 9,000 season tickets.[41][42]

In response to a disparity between the East and West Divisions, it was decided in the middle of the season to grant the fourth-place Western team a playoff berth. There was speculation this was done in part to ensure Sacramento remained in playoff contention as long as possible and at the insistence of Ryckman, who preferred the revenue of two playoff games for his first-place Stampeders over a first-round bye.

1994

[edit]

In 1994 the Gold Miners were joined by three other American teams: the Las Vegas Posse, Baltimore CFL Colts, and Shreveport Pirates. On television ESPN and its subsidiary ESPN2 picked up some games alongside the usual broadcasting by TSN and CBC in Canada.[43] Shreveport and Baltimore were placed in the East Division, while Sacramento and Las Vegas were placed in the West.[44] The playoffs were expanded again to eight teams (four per division). Another franchise was to have been added in Orlando; however, in a debacle that had now become a pattern, the presumptive ownership group failed to appear at the January 1994 press conference announcing the team's formation.[45]

The Baltimore CFL Colts made headlines before even playing a down. Owned by Jim Speros, the team was marketed as a revival of the Baltimore Colts NFL franchise, who had left the city 10 years earlier and had also played at Memorial Stadium. The team's embrace of the Colts' history gained them an instant following in Baltimore and publicity in the national sports media,[46] although an injunction obtained shortly before the team's first game forced the team to stop using "Colts" in their name and to instead refer to the team as the "Baltimore CFLers" or "Baltimore Football Club".[47] Since Memorial Stadium had originally been built to accommodate Major League Baseball's Baltimore Orioles as well as football, its playing surface was large enough to accommodate a full-size Canadian field.

Baltimore was far and away the most successful of any American CFL team both the field and off, averaging crowds of over 37,000 their first year.[48] Knowing that Canadian football was considerably different from the American game, Speros stocked the Baltimore club mostly with CFL veterans. As coach, he brought in Don Matthews, who had already played in two Grey Cups and won one.[49] The result was a team that eventually finished second in the East with a 12–6 record and became the first American team to qualify for the playoffs, advancing all the way to the Grey Cup game. In a thrilling match played in BC Place, the BC Lions defeated Baltimore on a last-second field goal by Lui Passaglia.[39] Perhaps most remarkably, they were reported to have turned a profit in their first year after an initial US$7 million investment by Speros.[50]

| 1994 Regular Season Attendance Figures | |||

| Team | Average | High | Low |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baltimore FC[51] | 37,347 | 42,116 | 31,172 |

| Las Vegas Posse[52] | 9,527 | 14,432 | 2,350 |

| Sacramento Gold Miners[53] | 14,226 | 17,192 | 12,633 |

| Shreveport Pirates[54] | 17,871 | 32,011 | 12,465 |

| Canadian average[55] | 22,740 | 51,180 | 11,248 |

The Shreveport Pirates were actually a transplantation of Bernie Glieberman and his organization from Ottawa. The Gliebermans had hinted at moving the Rough Riders to the United States, making them even more unpopular than they already were in Canada's capital. As part of a settlement with the CFL, Glieberman sold the Rough Riders to Bruce Firestone for CA$1.85 million, and in return was granted a US-based expansion team which became the Shreveport Pirates.[56] As part of the deal, Glieberman not only had to pay the expansion fee, but also had to settle his previous Ottawa debts.[57] There was a groundswell of local support for the club, but also significant difficulties in its first year, including stifling weather, cultural clashes, organizational gaffes, and serious hints of under-capitalization (during training camp the team was housed in a dorm above a milking barn). A woeful record did not help, as the team lost its first 14 games.[58] The Pirates showed some promise at the end of the season, reeling off a 3–1 record in their final four games; attendance also jumped, and the home finale drew over 32,000 fans to 40,000-seat Independence Stadium, the highest for any U.S.-hosted CFL game outside Baltimore.[59]

The Gold Miners, after spending much of 1993 adjusting to the Canadian game, rebounded strongly to finish 9–8–1 in their second season, three points short of the playoffs.[60] They were led again by David Archer at quarterback, who had persisted with the team since its World League days as the Sacramento Surge. However, in what was to become a trend during the CFL expansion, the second Sacramento season saw an attendance decline.[61]

At the other end of the spectrum, the Posse were an abject failure both on the field and off. Playing in Sam Boyd Stadium on the outskirts of the city and practicing on an ersatz practice field in the parking lot of the Riviera Hotel and Casino on the Las Vegas Strip, the team became infamous for botched gimmicks.[62] Attendance, never good to begin with, dropped to embarrassing levels as the season went on. With such dreadful gates, the team's cash flow dwindled to the point that, according to one assistant coach, "we couldn't even afford paper." After only 2,350 attended an October home game against Winnipeg (the lowest-attended match since the CFL's founding in 1958), owner Nick Mileti announced the team was suspending operations. To avoid shuttering a team mid-season, the league moved the Posse's final home game to Edmonton.[63] The team was little better on the field, finishing 5–13—the second-worst record in the league (ahead of only the Pirates).[64]

1994–1995 offseason

[edit]The Las Vegas situation was one of a bevy of developments faced by the league in the 1994–1995 offseason. The Posse were officially disbanded in April 1995, but not before the CFL damaged its credibility by twice granting provisional approval for the franchise's relocation, first to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, then to Jackson, Mississippi. The Milwaukee bid was to be owned by Marvin Fishman and use Milwaukee County Stadium, which for the previous four decades had hosted Green Bay Packers home games in Milwaukee before the Packers decided to move their entire home schedule to Lambeau Field beginning in 1995; while County Stadium's main tenants, the Milwaukee Brewers, accepted the Packers, the idea of sharing the venue with a CFL team whose schedule substantially overlapped with Major League Baseball led them to reject the relocation.[65] The Mississippi team was even included on the 1995 internal schedule and had hired a general manager and coaching staff, only for the deal to collapse amid squabbles with the Las Vegas corporation that owned the Posse.[66] A group from Miami, Florida, tried to convince the league to let it buy the remains of the Posse and move them to South Florida as the Miami Manatees, to play in the Miami Orange Bowl.[67] An exhibition game between Birmingham and Baltimore was held there in June 1995 to gauge support, which drew a decent crowd just above 20,000.[24]

The Gold Miners grew increasingly dissatisfied with Hornet Stadium, and Anderson blamed losses of US$10 million over two years on the facility. After attempts to have Sacramento State upgrade or replace the facility failed, he announced in October 1994—with two weeks to go in the season—that the Gold Miners would be playing elsewhere in 1995. Anderson initially intended to move to Oakland, but quickly abandoned those plans after it became apparent that Los Angeles Raiders owner Al Davis was seriously considering moving his NFL franchise back to its original city (the move came to pass). The Gold Miners eventually moved to the Alamodome in San Antonio, Texas, where they played as the San Antonio Texans.[68]

With the Posse folding, the Gold Miners moving, and the Pirates facing money troubles, three of the four CFL expansion teams had stumbled. The league, however, still managed to expand into two new markets for the 1995 season. The Memphis Mad Dogs were announced in November 1994, followed by the Birmingham Barracudas in January 1995.[69][70] The Memphis deal was hailed as a large step forward for the league's presence in the U.S., as it brought in the wealth of team owner Fred Smith (the founder and CEO of Federal Express) and his marketing connections.[69]

1995

[edit]With these changes, the CFL abandoned its longstanding east–west divisional format in favour of a north–south format for 1995. The five American teams—Baltimore, Birmingham, Memphis, San Antonio, and Shreveport—would be placed in the South Division, while the eight Canadian teams were included in the North Division. The top five Canadian teams and top three American teams would qualify for the playoffs; the fifth-seeded North team would "cross over" to the South playoffs, for a total of four teams per playoff bracket.[71] The league gained its first national American television contract with ESPN2, which agreed to televise more than 20 regular season games, plus the playoffs. The deal was reportedly worth about $1.5 million (equivalent to $3 million in 2023).[72] The CFL would remain on the network until 1997.

The Birmingham Barracudas, owned by insurance tycoon Art Williams, entered the league playing at Legion Field, which could accommodate a Canadian football field with 15-yard end zones (five yards shorter than the standard 20 yards). Led by future Hall of Famer Matt Dunigan at quarterback, the Barracudas fell short of the South Division title, but remained competitive throughout the year. Despite selling only 2,000 season tickets and facing community apathy after numerous attempts at pro football squads had failed in the city, attendance for the first three games exceeded expectations.[73] Williams knew that the 'Cudas potentially faced serious attendance problems once the traditional American football season began, and persuaded the CFL to let them play their late-season home games on Sunday afternoons – something the league had avoided in order to avoid putting its television broadcasts in direct competition with the NFL's. Williams calculated that competing with the NFL on television was a more reasonable risk to take compared to competition with local high school and Alabama/Auburn college football. Despite the time change, attendance still dropped to unsustainable levels; none of the final four home games attracted more than 10,000 people.[74] Williams claimed to have lost at least US$10 million on the season—at least as much as his startup costs—and blamed fan apathy for the attendance woes.[73]

Memphis had been a prime target for either expansion or relocation, as it was near Shreveport and San Antonio. In 1995, Fred Smith's ownership group, which had narrowly missed out on an NFL team, was awarded a CFL franchise to begin play as the Memphis Mad Dogs.[75] The Mad Dogs played in the Liberty Bowl, which had to be heavily reconfigured to accommodate the Canadian game. Astroturf sections were added around the grass field to accommodate the required width, while the expansion of the length of the field to 110 yards forced the end zones to become half Astroturf pentagons that averaged seven yards in the corners and fourteen yards behind the uprights. The grandstands stood mere yards from the end line, prompting veteran CFL quarterback Danny McManus to call the end zones "a lawsuit waiting to happen."[76]

Like Williams, Smith knew the Mad Dogs would face an uphill battle attracting fans once the traditional American football season started. As was the case in Birmingham, Smith persuaded the CFL to let the Dogs play their late-season home games on Sundays to avoid competing against high school and Tennessee/Ole Miss football. It was of no avail; late in the season the Mad Dogs struggled to attract more than 10,000 people.[77] Like Williams, Smith publicly blamed community apathy and media hostility for the lackluster attendance.[78] The team went 9–9 in their only year.

In Shreveport, meanwhile, whatever positive momentum the Pirates had gained at the end of the 1994 season failed to carry over into 1995. Despite the signing of former NFL quarterback Billy Joe Tolliver, who put up decent numbers, the squad limped to a 5–13 record. As elsewhere, Shreveport saw a second season attendance decline, and with the season winding down, the city had clearly soured on the Gliebermans. They became embroiled in legal difficulties and, in one particularly absurd incident, Bernie Glieberman had his lawyer attempt (unsuccessfully) to abscond with a half-million dollar Tucker automobile that Glieberman had donated to a local museum.[79]

Freshly relocated from Sacramento, the San Antonio Texans finally found success on the field in 1995 playing in the brand new Alamodome. The Alamodome offered two advantages over other U.S. facilities – it was a multi-purpose facility with retractable seating that could accommodate a full size CFL field, and it was an indoor, air-conditioned facility, meaning the teams playing there did not have to deal with the summer heat. The team continued to be bankrolled by the enthusiastic Fred Anderson.[80] Archer, entering his fifth year as Anderson's quarterback, led the second best offence in the league; he nevertheless suffered an injury late in the season, prompting the team to hire 45-year-old Joe Ferguson (whom Stephenson had coached as a member of the Buffalo Bills) out of retirement to serve as a backup.[81] They finished 12–6 and finally made the playoffs. In the first round they trounced Birmingham, 51–9, before falling to the Baltimore Stallions, 21–11, in the South Division final.[82] Team attendance was around the same level Anderson had previously seen in Sacramento.[83]

| 1995 Regular Season Attendance Figures | |||

| Team | Average | High | Low |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baltimore Stallions[84] | 30,111 | 33,208 | 27,321 |

| Birmingham Barracudas[85] | 17,625 | 31,185 | 6,317 |

| Memphis Mad Dogs[86] | 13,691 | 20,183 | 7,830 |

| San Antonio Texans[87] | 15,855 | 22,043 | 10,027 |

| Shreveport Pirates[88] | 14,359 | 21,117 | 11,554 |

| Canadian figures[89] | 24,406 | 55,438 | 14,122 |

The Baltimore franchise finally received a permanent name, the "Baltimore Stallions."[90] Led by quarterback Tracy Ham and running back Mike Pringle, the Stallions started 2–3, but then steamrolled through the rest of the season, winning 13 games in a row to finish first in the South Division. They knocked off Winnipeg and then San Antonio in the South Division final. They faced the Calgary Stampeders in the 1995 Grey Cup in Regina, Saskatchewan and won convincingly, 37–20. The first and only American team to take the championship, the 1995 Stallions team has since acquired a reputation as one of the CFL's best ever.[91] At the time, their .756 winning percentage over their first two seasons was the best start for an expansion team in North American professional sports history.[92]

While the Stallions experienced a successful year on the field, and finished second to Edmonton in average attendance, the city's excitement of 1994 died down. Attendance declined, with season ticket sales dropping to around 17,000. Later reports suggested that attendance numbers had been inflated by giveaways and the team projected some losses in 1995. Despite these difficulties, the Stallions remained the model that lent the American expansion project credibility; other American owners looked to Baltimore in deciding on the future of their own teams.[93]

End of U.S. experiment

[edit]League troubles

[edit]Despite some positive initial attendance numbers, after three years it was clear that general American fan interest in Canadian football was sparse. Differences in the Canadian game, such as three downs and the larger field, had not been embraced south of the border. While the CFL had a small deal with ESPN2, a major television contract had not materialized; efforts by the league's U.S. teams to negotiate a deal with CBS Sports failed after the network managed to pick up college football rights for 1996.[94] There was no widespread national promotional effort for the league in the U.S., and the general preference to avoid competing with the NFL in major markets hurt its efforts to reach out to major media platforms.[95] Moreover, the July to November CFL season, designed to ensure the playoffs finish before Canada's harsh winters set in, forced most American teams to play the first half of the season in oppressive heat and the second half in competition with high school football, college football, and the NFL.

Tension had also arisen between the American and Canadian teams. As early as the 1994 Grey Cup, the American owners, led by Speros in Baltimore, were calling for numerous changes to accommodate the American teams and their potential fans. They proposed that the end zones be reduced to 15 yards in length, that the Grey Cup be played earlier in the year, that player quotas be removed for all teams, and that a league name change be considered.[96] By 1995, Mad Dogs coach Pepper Rodgers was openly disparaging Canadian rules and teams. Officials of the new American teams found that the Canadian clubs were hesitant to accommodate the new American audience.[97] The Canadian owners, for their part, refused to make any major changes to the rules, the schedule, or the name of the league; the only concession they made was to allow smaller field sizes in American stadiums that could not fit a regulation CFL field.

Agreement on rules and schedules might have been reached had the league achieved economic stability, but losses among American teams were drastic and widespread. In 1995 alone, Fred Anderson estimated that the U.S. teams had collectively lost more than US$20 million.[92] The Baltimore Sun provides a similar estimate of US$21 million.[98] The $10 million estimated loss in Birmingham was the most substantial, followed by US$4 to $6 million estimated for Anderson's Texans.[98][99] Memphis and Shreveport losses were estimated at US$3 million apiece.[98][100] The Baltimore losses were comparatively modest at US$1 to $1.5 million, but stung the league, given the prestige of the franchise.[93][98]

Canadian teams were facing their own troubles, particularly with attendance. The eight Canadian teams were down to an average of 22,740 in 1994, a drop of 3,000 from the previous year.[55] It marked the beginning of an historic trough in Canadian CFL attendance that would last for most of the 1990s. A massive league-wide season ticket drive was undertaken prior to 1995. Commissioner Larry Smith told the Rough Riders and Tiger-Cats that unless they sold more tickets, they would be forced to either fold or move. Ottawa owner Bruce Firestone went bankrupt after the 1994 season, placing the team in the hands of Horn Chen, who turned out to be its final owner. In Calgary, Ryckman suggested he would move the Stampeders to the United States unless fans stepped up with 16,000 season tickets.[101] While season ticket goals were met, the overall increase in attendance was modest in 1995 to 24,406 and would be wiped out the next year.[102] In Toronto, Bruce McNall's finances collapsed in the midst of revelations of financial wrongdoing,[103] and because Wayne Gretzky's salary relied on McNall, and John Candy had put his share in the team up for sale the day he died, hours before his death,[104] the Argonauts effectively had no owners; the team would be operated by league television partner TSN through the rest of the 1990s.

End game

[edit]With these troubles still fresh, the NFL then dealt the CFL's American expansion a critical blow. On November 6, 1995—the week of the South Division Final—Cleveland Browns owner Art Modell announced he was moving his NFL franchise to Baltimore for the following season.[46][105] A day after the game, the Stallions' owners called Commissioner Smith and requested a meeting in Toronto; Smith's summary of their position was "we'll pay our bills but we're done."[105] The Stallions had been broadsided by the announcement, even though rumors of the NFL's impending return to Baltimore had cropped up as early as September. Speros and other insiders initially did not believe Modell was serious, a belief shared for a time even by some NFL owners. Even as it became clear that the Browns' relocation threat was credible, they still hoped NFL owners known to be opposed to the Browns' relocation such as Pittsburgh's Dan Rooney and Buffalo's Ralph Wilson would persuade Modell to come to terms with Cleveland. Nonetheless, by November the rumors were enough to seriously impair the Stallions' marketing efforts, and attendance for the team's semi-final against Winnipeg (played two days before the Browns' announcement) was a franchise low of 21,040.[46]

Once the Browns' move became official, what remained of local support for the Stallions dried up almost overnight. The team responded with desperate measures, essentially giving away thousands of tickets for what would become the final CFL game played in the United States, and announced a respectable attendance of 30,217 for their South Division Final victory over San Antonio. It was to no avail; the Grey Cup victory celebration in Inner Harbor went almost unnoticed in local media.[46]

Speros quickly realized that as successful as the Stallions had been, they could not even begin to compete with an NFL team. While Baltimore Mayor Kurt Schmoke (one of the few dignitaries to attend the Stallions' championship celebration) and some others claimed it was possible that the Stallions could coexist with Modell's team (which was ultimately reconstituted as the Baltimore Ravens following a settlement between Modell, the NFL and the city of Cleveland) it soon became apparent that there wasn't enough advertising revenue or fan support to go around. Additionally, the Stallions would have faced serious logistical problems with Memorial Stadium once the NFL season started in September. Speros said years later that all of this led him to conclude that the Stallions would have effectively been reduced to "minor league" status had they stayed in Baltimore.[46]

Speros began talks with Richmond, Norfolk, the Lehigh Valley, and, most seriously, Houston, which was about to lose the NFL's Oilers.[92] At one point, he was prepared to move to Houston and play in the Astrodome, and also intended to take on then-Houston Astros owner Drayton McLane as a minority partner.[46] Williams had decided to get out even before Baltimore's fate was announced; a day after the Barracudas were eliminated from the playoffs (and a day before the Browns announced they were leaving Cleveland), he announced that the squad would not be playing in Birmingham in 1996, if it returned at all.[73] Earlier, he had stated that he was not willing to play another season in Birmingham unless the league moved to a spring schedule; he felt it would be folly to risk another season going head-to-head with Alabama and Auburn.[92]

The end came swiftly in the months after the Grey Cup. By the time of a December 1 CFL Board of Governors meeting, the Mad Dogs had folded and the Barracudas were on the brink.[106][107] The Pirates held out a little longer and flirted with a relocation to Norfolk, but local officials broke off talks after they learned that Glieberman was still facing legal disputes in Shreveport.[56] The Barracudas resurfaced in the news in January 1996 when Williams sold them for $750,000 to a group that planned to move them to Shreveport as a replacement for the Pirates. However, that deal was contingent upon the league approving the sale and relocation, which never happened.[108]

Smith had given the American teams until the end of January 1996 to decide whether they would return for the 1996 season. By then, sources were stating that four of the five American teams had "either folded, have no stadiums to play in or will not be permitted to be part of the CFL in 1996." Only the Stallions appeared to be able to take the field in some form for the 1996 season.[109] Of the American owners, Anderson was the most amenable to retaining an American-based team in 1996. While he initially stated that the league needed at least three other American teams for the Texans to be viable,[92] he was willing to bring the Texans back for 1996 if the Stallions moved to Houston, since this would have not only ensured two American teams but also an intrastate rivalry.[99] Anderson estimated that if there was even one other American team in the league, he could withstand annual losses of US$2 million indefinitely.[110] However, that scenario looked less and less likely, as Speros—under prodding from Smith—had begun serious discussions with officials in Montreal.[46][99]

Against this backdrop, a second round of league meetings was held on February 2, where all five American franchises, including the Stallions, were formally shuttered, bringing the CFL's American expansion to a close.[111] At the same time, former Stallions owner Speros was granted a "reactivated" Alouettes franchise in Montreal.[112] Stallions general manager Jim Popp and much of the Stallions' coaching and front office staff moved north to Montreal and much of the club's roster re-signed with the Alouettes.

Aftermath

[edit]

The entire league was once again based only in Canada beginning with the 1996 CFL season, with Smith describing the move as a "retrenchment". This, however, did not stem the troubles the teams were facing. With no expansion fee revenue to buoy them, eight of the nine teams would lose money in 1996.[113] The 84th Grey Cup was nearly canceled before the coffee shop chain Tim Hortons stepped in and provided enough sponsorship money to allow both competing teams to collect their paychecks.[114] The Rough Riders disbanded at the end of the season and the Stampeders declared bankruptcy after Ryckman was fined $250,000 for stock manipulation by the Alberta Securities Commission and barred from doing business in Alberta.[115][116] After the indictment of McNall, Ryckman was the second major architect of expansion to run afoul of the law; the Stampeders were later bought by Sig Gutsche via a receivership court for $1.6 million on April 3.[117][118]

Other legal troubles were left over in wake of the expansion collapse. Louisiana courts eventually ordered the Gliebermans to repay Shreveport US$1 million with interest; the dispute centered over whether the city had agreed to share losses or simply lent money to the ownership group.[119] Art Williams, enraged after discovering some American owners had received discounts and extended payment periods on their franchise fees, threatened litigation and at first refused to honour the balance of Matt Dunigan's sizable contract before the matter entered litigation.[120]

The expansion fees themselves were a significant legacy of the expansion effort. Smith claims US$14 to $15 million was brought in and that it saved the league. A more modest assessment suggests expansion saved the Stampeders and Tiger-Cats—both teams were undeniably in distress during the era—and that the other Canadian teams were able to maintain a semblance of stability.[120]

The post-expansion financial crisis would eventually elicit a response from the NFL. By the end of 1996, speculation was rampant that if the NFL placed a franchise in Toronto, it would mean the end of the CFL.[92] Instead, in exchange for a new player agreement between the leagues, the NFL provided the CFL franchises with marketing assistance and a $3 million loan in 1997.[121]

In 1999, World Wrestling Federation chairman Vince McMahon was offered the chance to buy the Argonauts, and countered with a proposal to buy the entire league and "have it migrate south", which the owners refused.[122] McMahon would instead partner with NBC to create the XFL, which would place teams in Birmingham, Las Vegas, and Memphis at the same stadiums as their respective CFL franchises previously played. Following massive losses, NBC and the WWF shuttered the XFL after one year, though it would return nineteen years later—conspicuously absent from any markets where the CFL resided (subsequent XFL owners would return to Las Vegas and to San Antonio in 2023[123][124]). Birmingham (the Iron and Stallions) and Memphis (Express and Showboats, the latter of which was brought to Memphis by Mad Dogs owner Fred Smith[125]) both hosted teams in the XFL's contemporary rivals, the Alliance of American Football and revived United States Football League, respectively. Baltimore owner Jim Speros would later briefly re-emerge as the original owner of the Virginia Destroyers of the United Football League but withdrew from the purchase before the team began play.[126]

The CFL re-gained financial stability in the 2000s, mostly thanks to enforcement of a salary cap, stricter standards of ownership, and increasingly lucrative television contracts negotiated with Canadian networks. The league has remained solely focused on its Canadian operations, with expansion efforts focused for decades on returning a stable team to Ottawa. The first attempt at a replacement for the Rough Riders, the Ottawa Renegades, played from 2002 to 2005.[127] A second attempt, the Ottawa RedBlacks launched in 2014 and have so far been a success under the ownership of Jeff Hunt's consortium. Further expansion efforts were limited to one-off games such as Touchdown Atlantic and Northern Kickoff in more distant Canadian markets until the late 2010s when the league commenced negotiations with Schooners Sports and Entertainment to place an expansion team in Atlantic Canada.

The re-establishment of the Montreal Alouettes remains as the major legacy of the American experiment. Commissioner Smith, under pressure from the CFLPA and keen to ensure Montreal's new team was a Grey Cup contender from the outset, persuaded the other eight CFL teams to permit an expansion draft in which the Alouettes were allowed to draft only Canadian players to allow the team to remain competitive under the more restrictive rule regime, finishing their first season 12–6 and advancing to the East Final. Eventually, Speros would sell the Alouettes to Robert Wetenhall, with Smith resigning as commissioner to become President of the team.[128] Wetenhall's patient ownership, and a move to the more intimate Percival Molson Memorial Stadium, returned the team to stability off the field while steering it to three Grey Cups on the field. Longtime Alouettes starting quarterback Anthony Calvillo was the last remaining active player that played for an American CFL team (Las Vegas) upon his retirement after the 2013 season.

Even after the end of U.S. expansion, American investors continued to be involved with the CFL for many years at the ownership level, notably in Calgary and Ottawa. By the end of the first decade of the 21st century, all extant franchises except Montreal had come under Canadian ownership, leaving the Alouettes' Wetenhall as the league's only American owner. Wetenhall sold his franchise back to the league prior to the start of the 2019 season, thus putting the CFL under exclusively Canadian-based ownership for the first time in decades.

Further U.S. expansion has been occasionally proposed informally.[129] However, the league itself has expressed little interest in these proposals and U.S. expansion has not been formally explored. The spectre of American CFL games has mainly been used as a device for satire and April Fool's Day jokes.[130] One potential expansion candidate that attracted media attention is the St. Louis Battlehawks. In addition to the Battlehawks' league, the XFL at the time, having discussed a partnership agreement with the CFL in 2021,[131] TSN writer Dave Naylor suggested in 2024 that St. Louis would be an ideal expansion candidate should the Battlehawks' current league, the United Football League, ever shut down. The Battlehawks outdrew all of the CFL's teams in 2024 in fan attendance.[132]

List of American CFL teams

[edit]Teams that played

[edit]Proposed teams that did not play

[edit]| Team | City | Stadium | Capacity | Owner | Scheduled to begin play |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milwaukee CFL team | Milwaukee, Wisconsin | County Stadium | 53,192 | Marvin Fishman | 1995 |

| Mississippi CFL team | Jackson, Mississippi | Mississippi Veterans Memorial Stadium | 60,492 | William L. Collins or Norton Herrick and/or Jimmy Buffett |

1995 |

| Miami Manatees | Miami, Florida | Miami Orange Bowl | 74,476 | Ron Meyer | 1996 |

| San Antonio Texans (1993) | San Marcos, Texas | Bobcat Stadium1[citation needed] | 15,218 | Larry J. Benson | 1993 |

| Shreveport Barracudas | Shreveport, Louisiana | Independence Stadium | 53,000 | Ark-La-Tex Football, Inc. | 1996 |

Post-expansion American media

[edit]For several years after the expansion era contract with ESPN ended in 1997, the CFL was absent from American television. At the end of 2001, the league began a relationship with the now-defunct America One network that would last until 2009. Coverage was relatively generous with 43 games, including the playoffs, covered in the last year.[133][134] A more modest deal of 14 games was negotiated with the NFL Network in 2010, which lasted two years.[135] The 2012 season began without a contract and the league resorted to internet broadcasts on ESPN3 until NBC Sports Network agreed to a 14-game regular season package of its own; unlike the NFL Network, NBC opted to broadcast games during the NFL preseason as well as cover the playoffs and Grey Cup.[136] Both the NBC and ESPN deals were renewed in 2013 with a slight scaling back of playoff coverage and ESPN2 also picking up a handful of games in the summer months.[137] Since 2013, CFL games have been broadcast exclusively on the ESPN networks in the United States;[138] American broadcasts have been simulcasts of game coverage from TSN,[139] of which current U.S. broadcaster ESPN is a minority shareholder.

In the 2018 CFL season, CFL broadcasts on ESPN attracted an average of 163,000 U.S. viewers per game, which accounted for about one-fifth of the total North American television audience.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- List of National Football League games played outside the United States

- CFL USA all-time records and statistics

Notes

[edit]- ^ "New football league hope slim // CFL 'lukewarm' to merger with the defunct USFL", Chicago Sun-Times, February 18, 1987, archived from the original on March 9, 2016, retrieved July 4, 2012 – via HighBeam

- ^ a b c "Home away from home has happened before for Ticats". Hamilton Spectator. September 21, 2011. Archived from the original on October 24, 2017. Retrieved November 3, 2013.

- ^ a b "Tiger-Cats trounce Argos before 18,146 Buffalo fans". Ottawa Citizen. August 13, 1951. Archived from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved November 3, 2013.

- ^ a b "7,511 Fans Watch Calgary Beat Roughrider Gidders". Spokane Daily Chronicle. August 2, 1961. Archived from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- ^ a b "Lions kick way to win". Leader-Post. July 10, 1967. Archived from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved November 6, 2013.

- ^ "Hamilton vanquished Ottawas in exhibition game at New York saturday". Ottawa Citizen. December 13, 1909. Archived from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- ^ "History". Canadian Football League. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2013.

- ^ "Toronto Argonauts 11 vs Hamilton Tiger-Cats 17". Canadian Football League Database. Archived from the original on November 9, 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2013.

- ^ "Edmonton Eskimos 29 vs BC Lions 8". Canadian Football League Database. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2013.

- ^ "Eskimoes-Lions exhibition draws 10,000 at Portland". Ottawa Citizen. August 3, 1957. Archived from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved November 3, 2013.

- ^ "Edmonton Eskimos 9 vs BC Lions 6". Canadian Football League Database. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- ^ "Esks extended in 'Frisco tilt". Leader-Post. August 12, 1957. Archived from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- ^ "Ottawa Rough Riders 18 vs Hamilton Tiger-Cats 24". Canadian Football League Database. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- ^ "15,000 Fans at Philadelphia See Canadian League Football Game". The New York Times. September 14, 1958. Archived from the original on February 4, 2014. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- ^ "Canadian Football Invasion Pleases Philadelphia Fans". The Register-Guard. September 15, 1958. Archived from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- ^ "BC Lions 7 vs Winnipeg Blue Bombers 13". Canadian Football League Database. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- ^ "Blue Bombers shade lions". Saskatoon Star-Phoenix. July 30, 1960. Archived from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- ^ "Saskatchewan Roughriders 3 vs BC Lions 13". Canadian Football League Database. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- ^ "Saskatchewan Roughriders 7 vs Calgary Stampeders 14". Canadian Football League Database. Archived from the original on December 2, 2013. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- ^ "Stamps bounce Riders in 88 Degree Heat". Calgary Herald. August 2, 1961. Archived from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- ^ "Edmonton Eskimos 2 vs BC Lions 7". Canadian Football League Database. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved November 6, 2013.

- ^ a b "Toronto Argonauts 1 vs Calgary Stampeders 20". Canadian Football League Database. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ "Baltimore Stallions 37 vs Birmingham Barracudas 0". Canadian Football League Database. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ a b "20,250 at OB moves CFL closer to Miami". Miami Herald. June 25, 1995. Archived from the original on February 18, 2014. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ a b Woods, Paul. "The CFL on NBC — how it happened, and how it went so wrong in 1982". bouncingbackbook.ca. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ Cosentino, Dom. "Every Game Was Terrible: The Year The CFL Failed To Conquer America". Deadspin. Archived from the original on January 4, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ Hickey, Pat (November 11, 1987). "CFL May Be Beyond Rescuing". Montreal Gazette. Archived from the original on January 4, 2014. Retrieved January 2, 2014 – via Chicago Tribune.

- ^ a b c Willes (2013). End Zones. pg. 16–18.

- ^ "'I really pissed off Gretzky:' Former Kings owner McNall". The Sporting News. November 21, 2013. Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ Willes (2013). End Zones. pp. 70–79.

- ^ Cox, Damien (August 11, 1995). "Bills expect compensation if NFL comes to Toronto". Toronto Star.

- ^ Willes (2013). End Zones. pp. 60–63

- ^ Willes (2013). End Zones. pp. 19–22

- ^ "McNall Pleads Guilty". The Chicago Tribune. December 15, 1994. Archived from the original on December 28, 2013. Retrieved December 27, 2013.

- ^ Willes (2013). End Zones. pp. 77–78.

- ^ "New book by Willes explores the CFL's American era". Regina, Saskatchewan: Leader Post. November 23, 2013. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved December 27, 2013.

- ^ a b c Willes (2013). End Zones. pp. 26–29.

- ^ Willes (2013). End Zones. pg. 57

- ^ a b Farber, Michael (December 5, 1994). "It was a B.C. Year Pro Football". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on November 13, 2013. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- ^ "1993 Regular Season Standings". CFL. Archived from the original on July 29, 2009. Retrieved January 28, 2014.

- ^ "1993 CFL Attendance". Canadian Football League Database. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved January 28, 2014.

- ^ Willes (2013). End Zones. pg. 31.

- ^ "Canadian Football League 1994 Season Schedule". Canadian Football League Database. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved January 29, 2014.

- ^ "1994 Regular Season Standings". CFL. Archived from the original on July 15, 2009. Retrieved January 29, 2014.

- ^ Willes (2013). End Zones. pp. 57–58.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Baltimore's Forgotten Champions: An Oral History". Capital News Service (University of Maryland). Archived from the original on March 30, 2014. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- ^ Farber, Michael (July 25, 1994). "But Don't Call Them The Colts". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on November 13, 2013. Retrieved February 11, 2014.

- ^ "The Baltimore CFL Colts' 1994 Season". Canadian Football League Database. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved January 29, 2014.

- ^ Willes (2013). End Zones. pp. 83–86.

- ^ Steadman, John (November 2, 1994). "CFL marvel: A profitable debut year". Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved January 29, 2014.

- ^ "The Baltimore CFL Colts' 1994 Season". Canadian Football League Database. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved February 11, 2014.

- ^ "The Las Vegas Posse' 1994 Season". Canadian Football League Database. Archived from the original on February 19, 2014. Retrieved February 11, 2014.

- ^ "The Sacramento Gold Miners' 1994 Season". Canadian Football League Database. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved February 11, 2014.

- ^ "The Shreveport Pirates' 1994 Season". Canadian Football League Database. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved February 11, 2014.

- ^ a b "Canadian Football League Attendance: 1994". Canadian Football League Database. Archived from the original on February 19, 2014. Retrieved February 5, 2014.

- ^ a b "Back in town again". CBC Sports, June 9, 2005.

- ^ Willes (2013). End Zones. pp. 61–63

- ^ Willes (2013). End Zones. pp. 64–70

- ^ "The Shreveport Pirates' 1994 Season". Canadian Football League Database. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved January 29, 2014.

- ^ "CFL Standings - CFL.ca". CFL.ca.

- ^ "The Sacramento Gold Miners' 1994 Season". Canadian Football League Database. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved January 29, 2014.

- ^ Willes (2013). End Zones. pp. 36–42

- ^ Willes (2013). End Zones. pp. 43–56.

- ^ "The Las Vegas Posse 1994 Season". Canadian Football League Database. Archived from the original on April 27, 2015. Retrieved May 8, 2015.

- ^ Prigge, Matthew J. (October 10, 2016). "Canadian Football in Milwaukee? It Almost Happened". Shepherd Express. Archived from the original on October 1, 2020. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ Murray, Ken (April 18, 1995). "CFL's fumbles raise credibility question". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on January 13, 2014. Retrieved January 12, 2014.

- ^ Salguero, Armando (March 8, 1995). "CFL in OB? Wayne may have rival". The Miami Herald. p. 3D.

- ^ "CFL to move out of Sacramento – are they Oakland bound?". Sports Business Daily. October 25, 1994. Archived from the original on February 23, 2014. Retrieved January 31, 2014.

- ^ a b "CFL has reason to believe they will be received in Graceland". Sports Business Daily. November 18, 1994. Archived from the original on February 23, 2014. Retrieved January 31, 2014.

- ^ "CFL expansion expected in Birmingham; what about the Posse". Sports Business Daily. January 11, 1995. Archived from the original on February 23, 2014. Retrieved January 31, 2014.

- ^ "1995 Regular Season Standings". CFL. Archived from the original on July 15, 2009. Retrieved February 2, 2014.

- ^ "Stallions' Speros optimistic about CFL-ESPN contract". The Baltimore Sun. July 13, 1995. Archived from the original on February 19, 2014. Retrieved February 2, 2014.

- ^ a b c "Cudas Apparently Through in Birmingham". Gadsden Times. Associated Press. November 7, 1995. Archived from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved January 29, 2014.

- ^ "The Birmingham Barracudas' 1995 Season". Canadian Football League Database. Archived from the original on February 23, 2014. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ "N.F.L. Expansion Surprise: Jacksonville Jaguars". The New York Times. December 1, 1993. Archived from the original on December 9, 2014. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- ^ Willes (2013). End Zones. pg. 158.

- ^ "The Memphis Mad Dogs' 1995 Season". Canadian Football League Database. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ "Memphis Owner Angered by Apathy". Times Daily. September 15, 1995. Archived from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved January 29, 2014.

- ^ Willes (2013). End Zones. pp. 68–69.

- ^ Willes (2013). End Zones. pg. 146.

- ^ "SPORTS PEOPLE: FOOTBALL; Ferguson, 45, Signs C.F.L. Deal". The New York Times. August 3, 1995. Archived from the original on August 22, 2017. Retrieved February 6, 2017.

- ^ "Canadian Football League 1995 Season Schedule". Canadian Football League Database. Archived from the original on February 19, 2014. Retrieved February 6, 2014.

- ^ "San Antonio Texans' 1995 Season". Canadian Football League Database. Archived from the original on February 19, 2014. Retrieved February 2, 2014.

- ^ "The Baltimore Stallions 1995 Season". Canadian Football League Database. Archived from the original on February 19, 2014. Retrieved February 11, 2014.

- ^ "The Birmingham Barracudas' 1995 Season". Canadian Football League Database. Archived from the original on February 23, 2014. Retrieved February 11, 2014.

- ^ "The Memphis Mad Dogs' 1995 Season". Canadian Football League Database. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved February 11, 2014.

- ^ "The San Antonio Texans' 1995 Season". Canadian Football League Database. Archived from the original on February 19, 2014. Retrieved February 11, 2014.

- ^ "The Shreveport Pirates' 1995 Season". Canadian Football League Database. Archived from the original on February 19, 2014. Retrieved February 11, 2014.

- ^ "Canadian Football League Attendance: 1995". Canadian Football League Database. Archived from the original on February 23, 2014. Retrieved February 5, 2014.

- ^ "Just call them the Stallions". The Baltimore Sun. July 8, 1995. Archived from the original on February 19, 2014. Retrieved February 2, 2014.

- ^ Willes (2013). End Zones. pp. 161–162.

- ^ a b c d e f Symonds, William C. (December 3, 1995). Canadian football is running out of plays. Bloomberg BusinessWeek. Retrieved August 13, 2013.

- ^ a b Willes (2013). End Zones. pg. 163.

- ^ "Football's CFL-USA teams tried to give NFL run for money". The Gadsden Times. March 23, 2008. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- ^ Murray, Ken (April 5, 1995). CFL suspends Posse, won't move it to Miss. The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved April 5, 1995.

- ^ Willes (2013). End Zones. pp. 123–124.

- ^ Willes (2013). End Zones. pp. 153–157.

- ^ a b c d "CFL tied to pro football railroad tracks". The Baltimore Sun. November 10, 1995. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- ^ a b c Ralph, Dan. "Speros reportedly close to pulling Stallions" Archived May 14, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Associated Press, January 26, 1996.

- ^ Willes (2013). End Zones. pg. 68.

- ^ "Not-so-friendly persuasion selling tickets in Canada". The Baltimore Sun. July 23, 1995. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved February 5, 2014.

- ^ "Canadian Football League Attendance: 1995". Canadian Football League Database. Archived from the original on February 23, 2014. Retrieved February 5, 2014.

- ^ Hofmeister, Sallie. "The Hard Fall of a Salesman". Ne.

- ^ Collins, Glenn (November 20, 1994). "John Candy, Comedic Film Star, Is Dead of a Heart Attack at 44". The New York Times. Retrieved January 26, 2012.

- ^ a b Willes (2013). End Zones. pp. 146–147.

- ^ Lambrecht, Gary (December 2, 1995). "Meetings end, but busy days ahead for CFL Number of teams, import quotas must be worked out". Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on November 9, 2014. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ^ "Team Folds in Memphis". The New York Times. December 1, 1995. Archived from the original on March 5, 2014. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ^ "Barracudas Bound for Shreveport?". Gadsden Times. January 7, 1996. Archived from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ^ "The CFL meets its destiny this week". Sports Business Daily. January 31, 1996. Archived from the original on February 20, 2014. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ^ Willes (2013). pg 31.

- ^ Willes (2013). End Zones. pg. 35.

- ^ "CFL's American experiment ends as Stallions move north to Montreal" Archived April 26, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Associated Press, February 3, 1996.

- ^ Willes (2013). End Zones. pg. 169.

- ^ Ralph, Dan (April 28, 2020). "CFL asks federal government for $150 million to help cope with shutdown". Canadian Press. Archived from the original on April 29, 2020. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ Willes (2013). End Zones. pp. 165–166

- ^ "Arizona Court of Appeals: Alberta Securities Commission v. Ryckman". FindLaw. Archived from the original on March 4, 2014. Retrieved February 5, 2014.

- ^ Cosentino, Frank (December 17, 2014). Home Again. Lulu.com. ISBN 9781312745476. Archived from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- ^ "Former Stamps owner Sig Gutsche dies at 64". Archived from the original on February 6, 2019. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- ^ Willes (2013). End Zones. pg. 69.

- ^ a b Willes (2013). End Zones. pp. 151–153.

- ^ "NFL Loan Helps Cfl With Another Season". Seattle Times. Bloomberg News Service. November 30, 1997. Archived from the original on January 7, 2014. Retrieved February 11, 2014.

- ^ Baines, Tim (April 1, 2007). "CANOE – SLAM! Sports – Wrestling – Wrestlemania 23: Vince McMahon Q&A". Slam.canoe.ca. Archived from the original on July 18, 2012. Retrieved March 2, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "XFL's Vegas Vipers get home, schedule for 2023 season". Las Vegas Review-Journal. January 5, 2023. Retrieved January 8, 2023.

- ^ Kerr, Jeff (July 25, 2022). "XFL announces eight host cities for relaunch in 2023; no New York, California teams for first time in league". CBS Sports.

- ^ Barnes, Evan (November 15, 2022). "Memphis Showboats return to USFL, will play at Simmons Bank Liberty Stadium in 2023". The Commercial Appeal.

- ^ Fairbank, Dave (2010-08-20). League office to take over prospective UFL franchise; Speros out as owner. Daily Press (Newport News, VA). Retrieved 2010-11-14.

- ^ "Report: No CFL franchise in Ottawa in '07". TSN.ca. September 28, 2008. Retrieved November 22, 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Willes (2013). End Zones. pp. 178–188.

- ^ Naylor, David (February 5, 2009). "Ex-NFLer wants CFL to expand to U.S." Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on March 11, 2014. Retrieved February 5, 2014..

- ^ Buchholz, Andrew (April 1, 2015). Toronto Argos win April Fool's Day with announcement of game against NFL's Bills Archived April 3, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. Yahoo! Sports. Retrieved April 2, 2015.

- ^ Seifert, Kevin (July 7, 2021). "XFL planning 2023 return after talks on partnership with CFL tabled". ESPN. Archived from the original on July 7, 2021. Retrieved September 27, 2021.

The XFL announced on Wednesday that it is planning to relaunch in 2023 after talks with the Canadian Football League about collaboration between the two leagues were tabled.

- ^ Naylor, Dave (October 3, 2024). "Naylor: If the UFL fails, I think it would behoove the CFL to add a team in St Louis". TSN. Retrieved October 29, 2024.

- ^ "CFL hits American airwaves". CBC. November 9, 2001. Archived from the original on February 23, 2014. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ "Canadian Football League – 2009 Schedule". America One. Archived from the original on March 4, 2014. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ "CFL to air on NFL Network". CFL. June 30, 2010. Archived from the original on March 4, 2014. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ Fang, Ken (July 21, 2012). "CFL Finally Has A US TV Contract; Games Air On NBC Sports Network". Fang's Bites. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved July 21, 2012.

- ^ "NBC Sports Network to showcase CFL in 2013". CFL. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ "60 CFL games to be delivered live on ESPN networks". June 26, 2013. Archived from the original on February 9, 2018. Retrieved February 8, 2018.

- ^ "FAQ about Broadcasts on CFLDB". Archived from the original on February 9, 2018. Retrieved February 8, 2018.

References

[edit]- Willes, Ed (2013). End Zones and Border Wars: The Era of American Expansion in the CFL. Madeira Park, BC: Harbour Publishing Co. ISBN 978-1-55017-614-8. Archived from the original on January 16, 2014. Retrieved January 15, 2014.

External links

[edit]- The CFL in America, on OurSportsCentral

- Canadian Football League

- Canadian football in the United States

- Canadian Football League divisions

- Sports organizations established in 1993

- Organizations disestablished in 1995

- 1993 establishments in the United States

- 1995 disestablishments in the United States

- Defunct Canadian football leagues

- Defunct sports leagues in the United States