Internet slang

| Internet |

|---|

|

|

|

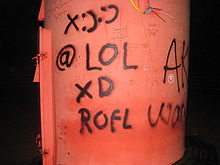

Internet slang (also called Internet shorthand, cyber-slang, netspeak, digispeak or chatspeak) is a non-standard or unofficial form of language used by people on the Internet to communicate to one another.[1] An example of Internet slang is "lol" meaning "laugh out loud." Since Internet slang is constantly changing, it is difficult to provide a standardized definition.[2] However, it can be understood to be any type of slang that Internet users have popularized, and in many cases, have coined. Such terms often originate with the purpose of saving keystrokes or to compensate for small character limits. Many people use the same abbreviations in texting, instant messaging, and social networking websites. Acronyms, keyboard symbols, and abbreviations are common types of Internet slang. New dialects of slang, such as leet or Lolspeak, develop as ingroup Internet memes rather than time savers. Many people also use Internet slang in face-to-face, real life communication.

Creation and evolution

[edit]Origins

[edit]Internet slang originated in the early days of the Internet with some terms predating the Internet.[3] The earliest forms of Internet slang assumed people's knowledge of programming and commands in a specific language.[4] Internet slang is used in chat rooms, social networking services, online games, video games and in the online community. Since 1979, users of communications networks like Usenet created their own shorthand.[5]

Motivations

[edit]The primary motivation for using a slang unique to the Internet is to ease communication. However, while Internet slang shortcuts save time for the writer, they take two times as long for the reader to understand, according to a study by the University of Tasmania.[6] On the other hand, similar to the use of slang in traditional face-to-face speech or written language, slang on the Internet is often a way of indicating group membership.[7]

Internet slang provides a channel which facilitates and constrains the ability to communicate in ways that are fundamentally different from those found in other semiotic situations. Many of the expectations and practices which we associate with spoken and written language are no longer applicable. The Internet itself is ideal for new slang to emerge because of the richness of the medium and the availability of information.[8] Slang is also thus motivated for the "creation and sustenance of online communities".[8] These communities, in turn, play a role in solidarity or identification[2][9] or an exclusive or common cause.[10]

David Crystal distinguishes among five areas of the Internet where slang is used- The Web itself, email, asynchronous chat (for example, mailing lists), synchronous chat (for example, Internet Relay Chat), and virtual worlds.[11] The electronic character of the channel has a fundamental influence on the language of the medium. Options for communication are constrained by the nature of the hardware needed in order to gain Internet access. Thus, productive linguistic capacity (the type of information that can be sent) is determined by the preassigned characters on a keyboard, and receptive linguistic capacity (the type of information that can be seen) is determined by the size and configuration of the screen. Additionally, both sender and receiver are constrained linguistically by the properties of the internet software, computer hardware, and networking hardware linking them. Electronic discourse refers to writing that is "very often reads as if it were being spoken – that is, as if the sender were writing talking".[12]

Types of slang

[edit]

Internet slang does not constitute a homogeneous language variety; rather, it differs according to the user and type of Internet situation.[13] Audience design occurs in online platforms, and therefore online communities can develop their own sociolects, or shared linguistic norms.[14][15]

Within the language of Internet slang, there is still an element of prescriptivism, as seen in style guides, for example Wired Style,[16] which are specifically aimed at usage on the Internet. Even so, few users consciously heed these prescriptive recommendations on CMC (Computer-mediated communication), but rather adapt their styles based on what they encounter online.[17] Although it is difficult to produce a clear definition of Internet slang, the following types of slang may be observed. This list is not exhaustive.

| Class | Description |

|---|---|

| Letter homophones | Included within this group are abbreviations and acronyms. An abbreviation is a shortening of a word, for example "CU" or "CYA" for "see you (see ya)". An acronym, on the other hand, is a subset of abbreviations and are formed from the initial components of each word. Examples of common acronyms include "LOL" for "laugh out loud", "BTW" for "by the way" and "TFW" for "that feeling when". There are also combinations of both, like "CUL8R" for "see you later". |

| Heterographs | Using one word in place of another, different but similarly sounding, word. Alternatively, a deliberate misspelling. For example, using "sauce" instead of "source" when asking for the source of an image or other posted material online.[18] For example, TikTok algorithms monitor 'explicit' content by censoring certain words or promoting videos based on the inclusion of certain hashtags; the intentional misspelling of words bypasses censorship guidelines and subsequently creates a range of platform-specific slang, renders trigger warnings as ineffective and can end up promoting harmful content (e.g. misspelling anorexia, pro-eating disorder content can be featured on the For You page via algorithms that promote popular content).[19] |

| Punctuation, capitalizations, and other symbols | Such features are commonly used for emphasis. Periods or exclamation marks may be used repeatedly for emphasis, such as "........" or "!!!!!!!!!!". Question marks and exclamation marks are often used together in strings such as "?!?!?!?!" when one is angry while asking a question. Grammatical punctuation rules are also relaxed on the Internet. "E-mail" may simply be expressed as "email", and apostrophes can be dropped so that "John's book" becomes "johns book". Examples of capitalizations include "STOP IT", which can convey a stronger emotion of annoyance as opposed to "stop it". Bold, underline and italics are also used to indicate stress. Using a tilde ~ can be a symbol of sarcasm, like "~That was so funny ~".[20] The period can also be used in a way to symbolize seriousness, or anger like "Ok." |

| Onomatopoeic or stylized spellings | Onomatopoeic spellings have also become popularized on the Internet. One well-known example is "hahaha" to indicate laughter. Onomatopoeic spellings are very language specific. For instance, in Spanish, laughter is spelled as "jajaja" instead because J is pronounced as /h/ (like English "h" in "hahaha") in Spanish. In Thai, it is "55555" because 5 in Thai ("ห้า") is pronounced /haː˥˩/. |

| Keyboard-generated emoticons and smileys | Emoticons are generally found in web forums, instant messengers, and online games. They are culture-specific and certain emoticons are only found in some languages but not in others. For example, the Japanese equivalent of emoticons, kaomoji (literally "face marks"), focus on the eyes instead of the mouth as in Western emoticons. They are also meant to be read right-side up, as in ^_^ as opposed to sideways, :3. More recently than face emoticons, other emoticon symbols such as <3 (which is a sideways heart) have emerged. Compared to emoticons used in Western cultures such as the United States, kaomoji play a very distinct social role in online discourse.[21][22] |

| Emojis | Emojis are relatively new to internet slang,[23] and are much like emoticons in the way that they convey messages in a visual way. However, while emoticons create an image using characters from the keyboard, emojis are a whole new level of communication and slang that portray messages in small cartoons. With culture comes different meaning for different emojis. For example, in 2016, Emojipedia and Prismoji took 571 peach emojis tweets and associated them with six different meanings varying from the fruit, feeling peachy, or sexual connotations.[24] |

| Leet | Leetspeak, or 1337,[25] is an alternative alphabet for the English language which uses various combinations of ASCII characters to replace Latinate letters. For example, Wikipedia may be expressed as "\/\/1|<1p3[)14". It originated from computer hacking, but its use has been extended to online gaming as well. Leet is often used today to set up effective security password for different accounts.[26] Leet is also used on social media platforms that employ content control algorithms to censor topics that may be controversial or inappropriate; using leet for potentially problematic terms (e.g. "k1ll"; "s3x"; "ant1s3m1t1sm") can avoid censorship. |

| Novel syntactic features | Unusual syntactic structures such as "I Can Has Cheezburger?" and "You are doing me a frighten" have been encouraged and spread by highly successful memes. Pluralization of "the internets" is another example, which has become common since it was used by George W. Bush during a televised event.[27] |

Views

[edit]Many debates about how the use of slang on the Internet influences language outside of the digital sphere go on. Even though the direct causal relationship between the Internet and language has yet to be proven by any scientific research,[28] Internet slang has invited split views on its influence on the standard of language use in non-computer-mediated communications.

Prescriptivists tend to have the widespread belief that the Internet has a negative influence on the future of language, and that it could lead to a degradation of standard.[11] Some would even attribute any decline of standard formal English to the increase in usage of electronic communication.[28] It has also been suggested that the linguistic differences between Standard English and CMC can have implications for literacy education.[29] This is illustrated by the widely reported example of a school essay submitted by a Scottish teenager, which contained many abbreviations and acronyms likened to SMS language. There was great condemnation of this style by the mass media as well as educationists, who expressed that this showed diminishing literacy or linguistic abilities.[30]

On the other hand, descriptivists have counter-argued that the Internet allows better expressions of a language.[28] Rather than established linguistic conventions, linguistic choices sometimes reflect personal taste.[31] It has also been suggested that as opposed to intentionally flouting language conventions, Internet slang is a result of a lack of motivation to monitor speech online.[32] Hale and Scanlon describe language in emails as being derived from "writing the way people talk", and that there is no need to insist on 'Standard' English.[16] English users, in particular, have an extensive tradition of etiquette guides, instead of traditional prescriptive treatises, that offer pointers on linguistic appropriateness.[31] Using and spreading Internet slang also adds onto the cultural currency of a language.[33] It is important to the speakers of the language due to the foundation it provides for identifying within a group, and also for defining a person's individual linguistic and communicative competence.[33] The result is a specialized subculture based on its use of slang.[34]

In scholarly research, attention has, for example, been drawn to the effect of the use of Internet slang in ethnography, and more importantly to how conversational relationships online change structurally because slang is used.[33]

In German, there is already considerable controversy regarding the use of anglicisms outside of CMC.[35] This situation is even more problematic within CMC, since the jargon of the medium is dominated by English terms.[13] An extreme example of an anti-anglicisms perspective can be observed from the chatroom rules of a Christian site,[36] which bans all anglicisms ("Das Verwenden von Anglizismen ist strengstens untersagt!" [Using anglicisms is strictly prohibited!]), and also translates even fundamental terms into German equivalents.[13]

Journalism

[edit]In April 2014, Gawker's editor-in-chief Max Read instituted new writing style guidelines banning internet slang for his writing staff.[37][38][39][40][41][42] Internet slang has gained attraction, however in other publications ranging from Buzzfeed to The Washington Post, gaining attention from younger viewers. Clickbait headlines have particularly sparked attention, originating from the rise of Buzzfeed in the journalistic sphere which ultimately lead to an online landscape populated with social media references and a shift in language use. [43]

Use beyond computer-mediated communication

[edit]Internet slang has crossed from being mediated by the computer into other non-physical domains.[44] Here, these domains are taken to refer to any domain of interaction where interlocutors need not be geographically proximate to one another, and where the Internet is not primarily used. Internet slang is now prevalent in telephony, mainly through short messages (SMS) communication. Abbreviations and interjections, especially, have been popularized in this medium, perhaps due to the limited character space for writing messages on mobile phones. Another possible reason for this spread is the convenience of transferring the existing mappings between expression and meaning into a similar space of interaction.[45]

At the same time, Internet slang has also taken a place as part of everyday offline language, among those with digital access.[44] The nature and content of online conversation is brought forward to direct offline communication through the telephone and direct talking, as well as through written language, such as in writing notes or letters. In the case of interjections, such as numerically based and abbreviated Internet slang, are not pronounced as they are written physically or replaced by any actual action. Rather, they become lexicalized and spoken like non-slang words in a "stage direction" like fashion, where the actual action is not carried out but substituted with a verbal signal. The notions of flaming and trolling have also extended outside the computer, and are used in the same circumstances of deliberate or unintentional implicatures.[8]

The expansion of Internet slang has been furthered through codification and the promotion of digital literacy. The subsequently existing and growing popularity of such references among those online as well as offline has thus advanced Internet slang literacy and globalized it.[46] Awareness and proficiency in manipulating Internet slang in both online and offline communication indicates digital literacy and teaching materials have even been developed to further this knowledge.[47] A South Korean publisher, for example, has published a textbook that details the meaning and context of use for common Internet slang instances and is targeted at young children who will soon be using the Internet.[48] Similarly, Internet slang has been recommended as language teaching material in second language classrooms in order to raise communicative competence by imparting some of the cultural value attached to a language that is available only in slang.[49]

Meanwhile, well-known dictionaries such as the ODE[50] and Merriam-Webster have been updated with a significant and growing body of slang jargon. Besides common examples, lesser known slang and slang with a non-English etymology have also found a place in standardized linguistic references. Along with these instances, literature in user-contributed dictionaries such as Urban Dictionary has also been added to. Codification seems to be qualified through frequency of use, and novel creations are often not accepted by other users of slang.[51]

Present

[edit]Although Internet slang began as a means of "opposition" to mainstream language, its popularity with today's globalized digitally literate population has shifted it into a part of everyday language, where it also leaves a profound impact.[52]

Frequently used slang also have become conventionalised into memetic "unit[s] of cultural information".[8] These memes in turn are further spread through their use on the Internet, prominently through websites. The Internet as an "information superhighway" is also catalysed through slang.[34] The evolution of slang has also created a 'slang union'[2] as part of a unique, specialised subculture.[34] Such impacts are, however, limited and requires further discussion especially from the non-English world. This is because Internet slang is prevalent in languages more actively used on the Internet, like English, which is the Internet's lingua franca.[53][54]

Around the world

[edit]

In Japanese, the term moe has come into common use among slang users to mean something "preciously cute" and appealing.[55]

Aside from the more frequent abbreviations, acronyms, and emoticons, Internet slang also uses archaic words or the lesser-known meanings of mainstream terms.[2] Regular words can also be altered into something with a similar pronunciation but altogether different meaning, or attributed new meanings altogether.[2] Phonetic transcriptions are the transformation of words to how it sounds in a certain language, and are used as internet slang.[56] In places where logographic languages are used, such as China, a visual Internet slang exists, giving characters dual meanings, one direct and one implied.[2]

The Internet has helped people from all over the world to become connected to one another, enabling "global" relationships to be formed.[57] As such, it is important for the various types of slang used online to be recognizable for everyone. It is also important to do so because of how other languages are quickly catching up with English on the Internet, following the increase in Internet usage in predominantly non-English speaking countries. In fact, as of January 2020, only approximately 25.9% of the online population is made up of English speakers.[58]

Different cultures tend to have different motivations behind their choice of slang, on top of the difference in language used. For example, in China, because of the tough Internet regulations imposed, users tend to use certain slang to talk about issues deemed as sensitive to the government. These include using symbols to separate the characters of a word to avoid detection from manual or automated text pattern scanning and consequential censorship.[59] An outstanding example is the use of the term river crab to denote censorship. River crab (hexie) is pronounced the same as "harmony"—the official term used to justify political discipline and censorship. As such Chinese netizens reappropriate the official terms in a sarcastic way.[60]

Abbreviations are popular across different cultures, including countries like Japan, China, France, Portugal, etc., and are used according to the particular language the Internet users speak. Significantly, this same style of slang creation is also found in non-alphabetical languages[2] as, for example, a form of "e gao" or alternative political discourse.[10]

The difference in language often results in miscommunication, as seen in an onomatopoeic example, "555", which sounds like "crying" in Chinese, and "laughing" in Thai.[61] A similar example is between the English "haha" and the Spanish "jaja", where both are onomatopoeic expressions of laughter, but the difference in language also meant a different consonant for the same sound to be produced. For more examples of how other languages express "laughing out loud", see also: LOL

In terms of culture, in Chinese, the numerically based onomatopoeia "770880" (simplified Chinese: 亲亲你抱抱你; traditional Chinese: 親親你抱抱你; pinyin: qīn qīn nǐ bào bào nǐ), which means to 'kiss and hug you', is used.[61] This is comparable to "XOXO", which many Internet users use. In French, "pk" or "pq" is used in the place of pourquoi, which means 'why'. This is an example of a combination of onomatopoeia and shortening of the original word for convenience when writing online.

In conclusion, every different country has their own language background and cultural differences and hence, they tend to have their own rules and motivations for their own Internet slang. However, at present, there is still a lack of studies done by researchers on some differences between the countries.

On the whole, the popular use of Internet slang has resulted in a unique online and offline community as well as a couple sub-categories of "special internet slang which is different from other slang spread on the whole internet... similar to jargon... usually decided by the sharing community".[9] It has also led to virtual communities marked by the specific slang they use[9] and led to a more homogenized yet diverse online culture.[2][9]

Internet slang in advertisements

[edit]This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (March 2024) |

Internet slang can make advertisements more effective.[62] Through two empirical studies, it was proven that Internet slang could help promote or capture the crowd's attention through advertisement, but did not increase the sales of the product. However, using Internet slang in advertisement may attract a certain demographic, and might not be the best to use depending on the product or goods. Furthermore, an overuse of Internet slang also negatively effects the brand due to quality of the advertisement, but using an appropriate amount would be sufficient in providing more attention to the ad. According to the experiment, Internet slang helped capture the attention of the consumers of necessity items. However, the demographic of luxury goods differ, and using Internet slang would potentially have the brand lose credibility due to the appropriateness of Internet slang.[62]

See also

[edit]- African-American Vernacular English (AAVE) – Variety of American English

- Cyberculture – Culture that has emerged from the use of computer networks

- Internet industry jargon – Jargon used by workers in the Internet industry

- English-language spelling reform – Proposed reforms to English spelling to be more phonetic

- Internet linguistics – Domain of linguistics

- Internet meme – Cultural item spread via the Internet

- Internet minute – internet slang

- Jargon File – Collection of definitions from computer subcultures

- Languages used on the Internet

- Lists of acronyms

- List of Generation Z slang

- Netiquette – Code of behavior for use of the Internet

- Roman and medieval abbreviations used to save space on manuscripts and epigraphs:

- Scribal abbreviations – Abbreviations used by ancient and medieval scribes

- Tironian notes – Roman shorthand system

- Typographic ligature – Glyph combining two or more letterforms

- TL;DR – "too long; didn't read"; internet comment

References

[edit]- ^ Zappavigna, Michele (2012). Discourse of Twitter and Social Media: How We Use Language to Create Affiliation on the Web. eBook. p. 127. ISBN 9781441138712.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h Yin Yan (2006) World Wide Web and the Formation of the Chinese and EnglishInternet Union". Computer-Assisted Foreign Language Education. Vol. 1. ISSN 1001-5795

- ^ Daw, David. "Web Jargon Origins Revealed". Pcworld.com. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ McCulloch, Gretchen (2019). Because Internet: Understanding the Rules of Language. New York: Riverhead Books. pp. 88–95. ISBN 9780735210950.

- ^ Meggyn. "Trolling For Slang: The Origins of Internet Werdz". Theunderenlightened.com. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ "Don't be 404, know the tech slang". BBC. 10 December 2008.

- ^ Crystal, David (1997). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language (Second ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b c d Flamand, E (2008). "The impossible task of dialog analysis in chatboxes".

- ^ a b c d Wei Miao Miao (2010) "Internet slang used by online Japanese anime fans." 3PM Journal of Digital Researching and Publishing. Session 2 2010 pp 91–98

- ^ a b Meng Bingchun (2011) "From Steamed Bun to Grass Mud Horse: E Gao as alternative political discourse on the Chinese Internet." Global Media and Communication April 2011 vol. 7 no. 1 33–51

- ^ a b Crystal, David (2001). Language and the Internet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-80212-1.

- ^ Davis, B.H.; Brewer, J. P. (1997). Electronic discourse: linguistic individuals in virtual space. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- ^ a b c Hohenhaus, Peter (2005). Elements of traditional and "reverse" purism in relation to computer-mediated communication. In Langer, Nils and Winifred V. Davies (eds.), Linguistic Purism in the Germanic Languages. Berlin/New York: de Gruyter, 203-220.

- ^ Pavalanathan, Umashanthi, and Jacob Eisenstein. "Audience-modulated variation in online social media." American Speech 90.2 (2015): 187-213.

- ^ Lucy, Li, and David Bamman. "Characterizing English variation across social media communities with BERT." Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 9 (2021): 538-556.

- ^ a b [Hale, C. and Scanlon, J (1999). Wired Style: Principles of English Usage in the Digital Age. New York: Broadway Books]

- ^ Baron, Naomi. (2000). Alphabet to Email. London: Routledge.

- ^ [1] Barseghyan, L. (2013). On some aspects of Internet slang. Graduate School of Foreign Languages N, 14, 19-31.

- ^ Sung, Morgan (31 August 2020). "It's almost impossible to avoid triggering content on TikTok". Mashable. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ Kimball Leslie, Jess (5 June 2017). "The Internet Tilde Perfectly Conveys Something We Don't Have the Words to Explain". Science of Us. Science of Us – via Vox Media, LLC.

- ^ Sugimoto, T. and Levin, J. A. (2000), Multiple Literacies and Multimedia: A Comparison of Japanese and American Uses of the Internet, In C. Self & G. Hawisher (Eds), Global literacies and the World-wide Web, London: Routledge

- ^ Katsuno, Hirofumi and Christine R. Yano (2002), Asian Studies Review 26(2): 205-231

- ^ Petra Kralj Novak; Jasmina Smailović; Borut Sluban; Igor Mozetič (2015). "Sentiment of emojis". PLOS ONE. 10 (12): e0144296. arXiv:1509.07761. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1044296K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0144296. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4671607. PMID 26641093. S2CID 5526153.

- ^ Azhar, Hamden (2016). "How We Really Use The Peach".

- ^ "1337 - what is it and how to be 1337". Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ Li, Zeng, Wanda, Jianping (January 2021). "Leet Usage and Its Effect on Password Security".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Menning, Chris (2000). "Internets".

- ^ a b c "Internet's Effect on Language Debated". Newjerseynewsroom.com. 20 January 2010. Archived from the original on 22 April 2012. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ^ Hawisher, Gale E. and Cynthia L. Selfe (eds). (2002). Global Literacies and the World-Wide Web. London/New York: Routledge

- ^ "BBC NEWS | UK | Is txt mightier than the word?". Newsvote.bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 3 September 2015. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ^ a b Baron, Naomi S. (2002). Who sets email style: Prescriptivism, coping strategies, and democratizing communication access. The Information Society 18, 403-413

- ^ Baron, Naomi (2003) "Why Email Looks Like Speech: Proofreading Pedagogy and Public Face." In New Media Language, ed. Jean Aitchison and Diana M. Lewis, 85–94. London: Routledge.

- ^ a b c Garcia, Angela Cora, Standlee, Alecea I., Beckhoff, Jennifer and Yan Cui. Ethnographic Approaches to the Internet and Computer-Mediated Communication. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography. Vol. 38 No. 1 pp 52–84

- ^ a b c Simon-Vandenbergen, Anne Marie (2008) Deciphering L33t5p34k: Internet Slang on Message Boards. Thesis paper. Ghent University Faculty of Arts and Philosophy

- ^ Hohenhaus, Peter. (2002). Standardization, language change, resistance and the question of linguistic threat: 18th-century English and present-day German. In: Linn, Andrew R. and Nicola McLelland (eds.). Standardization - Studies from the Germanic languages. Amsterdam: Benjamins (= Current Issues in Linguistic Theory volume 235), 153-178

- ^ [2]

- ^ Beaujon, Andrew (3 April 2014). "Gawker bans 'Internet slang'". Poynter Institute. Archived from the original on 28 November 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ^ Crugnale, James (3 April 2014). "Gawker Rips Buzzfeed in Ban on 'WTF,' 'Epic' and Other Internet Slang From Its Website". TheWrap. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ^ Kassel, Matthew (3 April 2014). "'Massive' Attack: Gawker Goes After Whopping Word". The New York Observer. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ^ Weaver, Alex (3 April 2014). "Gawker Editor Bans 'Internet Slang,' Challenges Staff to 'Sound Like Regular Human Beings'". BostInno. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ^ Poole, Steven (10 April 2014). "A ban on internet slang? That's derp". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ^ McWhorter, John (7 April 2014). "Gawker is Trying to Use 'Adult' Language. Good Luck to Them". The New Republic. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ^ Mormol, Paulina (January 2019). On the Linguistic Features of Buzzfeed Headlines. Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Rzeszowskiego.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b Crystal, David (20 September 2001). Language and the Internet. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-80212-1.

- ^ "Don't be 404, know the tech slang". BBC. 10 December 2008.

- ^ Wellman, Barry (2004) The glocal village: Internet and community. Arts and Science Review. University of Toronto. Issue 1, Series 1.

- ^ Singhal, M. (1997). "The Internet and foreign language education: Benefits and challenges". The Internet TESL Journal.

- ^ Ashcroft, Brian (2010) Hey Korean Kids, Let's Learn Leetspeak And Internet Slang. Published 11 February 2010. Retrieved from [3]

- ^ Quintana, M. (2004) Integration of Effective Internet Resources for Future Teachers of Bilingual Ed. National Association of African American Studies, 2004

- ^ "Oxford Dictionary official blog". Blog.oxforddictionaries.com. Archived from the original on 4 July 2011. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ Jones, Brian. "Rejects". Noslang.com. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ^

- Eller, Lara L. (2005). "Instant Message Communication and its Impact upon Written Language". Thesis. West Virginia University. "Alternate source". WVU Scholar.

- "Alternate source". University of Hong Kong.

- "Alternate source" (pdf). Research Gate.

- ^ "Learn English online: How the internet is changing language". BBC News. 14 December 2012.

- ^ "English - the universal language on the Internet?".

English essentially is the universal language of the Internet

- ^ "Moe - Anime News Network". www.animenewsnetwork.com. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ Wells, J.C. "Phonetic transcriptions and analysis". CiteSeerX 10.1.1.693.115.

- ^ Barry Wellman (2004). "The Glocal Village: Internet and Community." Ideas&s Vol 1:1

- ^ Johnson, Joseph (27 January 2021). "Most common languages used on the internet as of January 2020, by share of internet users". Statista.

- ^ Zhou Shuguang (2008). "Notes On The Net." Index on Censorship Vol 37:2

- ^ Nordin, Astrid and Richaud, Lisa (2014), "Subverting official language and discourse in China? Type river rrab for harmony," China Information 28, 1 (March): 47–67.

- ^ a b Crystal Tao (6 May 2010). "Why Thai Laugh When Chinese Cry?". Lovelovechina.com. Archived from the original on 20 April 2012. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ^ a b Liu S, Gui DY, Zuo Y, Dai Y (7 June 2019). "Good Slang or Bad Slang? Embedding Internet Slang in Persuasive Advertising". Frontiers in Psychology. 10: 1251. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01251. PMC 6566129. PMID 31231278.

Further reading

[edit]- Baron, Naomi S. (2000). Alphabet to E-mail: How Written English Evolved and Where It's Heading. London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-18685-4.

- Aunger, Robert (2002). The Electric Meme: A new theory of how we think. New York: Free Press. ISBN 9781451612950.

- Androutsopoulos, Jannis (2006). "Introduction: Sociolinguistics and computer-mediated communication". Journal of Sociolinguistics. 10 (4): 419–438. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9841.2006.00286.x.

- Baron, Naomi S. (2008). Always on: language in an online and mobile world. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-531305-5.

- Vizgirdaite, Jurgita (2009). "Filling the Child-Parent Relationship Gap via the Parent Self-Education and Intergenerational Education on Internet Slang". Socialiniai Mokslai [Social Sciences]. 64 (2). Kaunas University of Technology: 57–66. ISSN 1392-0758. Archived from the original on 28 December 2019. Alt URL

- Garber, Megan (2013). "English Has a New Preposition, Because Internet". The Atlantic. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- Pringle, Ramona. "Emojis are Everywhere and They're Changing How We Communicate". CBC News. CBC. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

External links

[edit]- Dictionaries of slang and abbreviations: