Bruton Smith

Bruton Smith | |

|---|---|

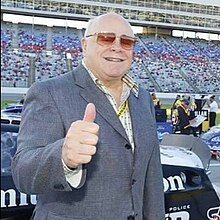

Smith at Texas Motor Speedway in 2005 | |

| Born | Ollen Bruton Smith March 3, 1927 Oakboro, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Died | June 22, 2022 (aged 95) |

| Occupation(s) | Racing promoter, race track owner, automobile dealer |

| Years active | 1949–2022 |

| Organization(s) | Speedway Motorsports, Inc. Sonic Automotive |

| Spouse |

Bonnie Jean Harris

(m. 1972; div. 1990) |

| Children | 5, including Marcus |

Ollen Bruton Smith (March 3, 1927 – June 22, 2022) was an American motorsports executive and businessman. He was best known as the owner of two public companies, Speedway Motorsports, Inc. (SMI) and Sonic Automotive. Smith held the positions of vice president and general manager of the Charlotte Motor Speedway and later was the chief executive officer (CEO) of both Speedway Motorsports and Sonic Automotive. He was an entrepreneur, race promoter, and businessman during the rise of stock car racing that began in the 1950s.

Smith was born and raised near Oakboro, North Carolina. In 1959, he and stock car racing driver Curtis Turner partnered to construct the Charlotte Motor Speedway, a 1.5-mile (2.4 km) banked racetrack in Concord, North Carolina. After the initial failure of the speedway, Smith went bankrupt, leading him to work in the car dealership business. After the success of his car dealership business, Smith bought back an interest in the speedway, eventually becoming its general manager in 1975. After a period of investing in businesses outside the auto-racing industry in the 1980s, Smith bought numerous tracks in the 1990s and 2000s, using the funds he had made after taking SMI public on the New York Stock Exchange in 1995. Two years later, he incorporated Sonic Automotive, a chain of car dealerships, becoming CEO of both SMI and Sonic Automotive.

Smith is widely regarded as one of the most influential businessmen in auto racing and a polarizing figure in the industry. Throughout his time as a businessman, he was known as an extravagant spender and someone who cared about details. He used his wealth and power to turn racetracks owned by Speedway Motorsports into world-class facilities and to turn Sonic Automotive into one of the biggest car dealership businesses in the United States. Businessmen who worked under Smith, including Humpy Wheeler and Eddie Gossage, viewed Smith highly for his actions. He was embroiled in numerous legal battles and controversies, including his divorce with his only wife and his reaction to opposition of construction of a drag strip at the Charlotte Motor Speedway.

Smith is also regarded as one of the key people in a rivalry between Smith's SMI and the NASCAR-owned International Speedway Corporation (ISC), a rivalry that has existed since Smith's start as a race promoter in the late 1940s. The two companies, created by Smith and NASCAR founder Bill France Sr., respectively, have engaged in a series of tense exchanges and lawsuits that have affected NASCAR's legacy and popularity to this day.

Early life

[edit]Smith was born in Oakboro, North Carolina, on March 3, 1927, to James Lemuel Smith (1875–1958) and Mollie C. Smith (1887–1982).[1] He was the youngest of nine children. The family lived a mile outside Oakboro, on a farming community.[2]

Growing up on a farm meant Smith's family had a home and enough to eat, but despite working from "sunup to sundown", they had little money. Smith "never did like that", and by the age of nine had decided he would leave the farm.[2] When he was 11, Smith began practicing with a home-made punching bag, and dreamed of becoming the middleweight champion of the world.[3] Smith practiced boxing for five years before quitting. He also recalled that he had numerous "crazy ideas" as a child: he saw a movie in which a tycoon owned a train and saw another featuring James Cagney owning a trucking company, and for a while decided that he wanted to own a train and a trucking company.[4]

Smith watched his first auto-racing event at the age of eight at the Charlotte Speedway.[5] In 1946, Smith began selling used cars from his front yard, operating the business for about five years, according to The Charlotte News.[6][7]

After graduating from Oakboro High School (now West Stanly High School) in 1944, he gained his first job in a hosiery mill. He bought his first race car at 17 for $700 ($12,116 when adjusted for inflation).[8] He claimed that on one occasion during his brief racing career, he managed to beat Buck Baker and Joe Weatherly, both of whom are considered early NASCAR pioneers. However, Smith's mother opposed the idea of his racing, praying that Smith would stop. Smith, stating that he could not "fight [his] mom and God", ceased racing.[5]

Business career

[edit]Early business ventures

[edit]NSCRA and the beginnings of a rivalry with the France family

[edit]Smith began promoting stock-car events as a 17-year-old in Midland, North Carolina, in the middle of a cornfield he nicknamed the "Dust Bowl".[2] In 1949, Smith took over the National Stock Car Racing Association (NSCRA), a league that had formed a year earlier in 1948 and was one of several fledgling stock-car sanctioning bodies that were direct competitors to NASCAR, which had been founded in the same year.[9] Early in the year, Smith announced the creation of a new division called the "Strictly Stock" division, which utilized newer models of stock cars instead of older, modified cars. As a response, NASCAR president Bill France Sr. created his own "Strictly Stock" division, holding its first Strictly Stock event on the same day that the NSCRA was planning to hold their Strictly Stock race, on June 19, 1949.[10] This event is considered by some NASCAR reporters and media members as the starting point of a rivalry between the Smith family and the France family, a rivalry that has grown since the creation of Speedway Motorsports and the International Speedway Corporation, founded by Bruton Smith and Bill France Sr., respectively.[11]

In 1951, Smith took over the lease of the Charlotte Speedway from Buck Baker, Roby Combs, and Ike Kiser to promote races at the speedway.[12] In the same year, France and Smith discussed merging their sanctioning bodies and came to a tentative agreement on the issue; however, Smith was drafted into the United States Army to fight in the Korean War in January 1951, becoming a paratrooper. When Smith returned to civilian life two years later, he found that poor leadership in his absence had caused the NSCRA to disband.[13][14]

Promotional career after Korean War

[edit]After his honorable discharge in 1953, Smith returned to his parents' home in Concord, North Carolina, living with his mother. For most of the 1950s, he sold cars and promoted local short-track races throughout the Carolinas, including races in Concord, Shelby, and Piedmont. In a 1982 interview with The Charlotte Observer, the retired president of the Charlotte Motor Speedway, Humpy Wheeler, stated that he believed Smith had managed to turn stock-car racing into a more professional environment, forcing drivers to take publicity pictures wearing a suit and tie.[15] Smith was also known to get into disagreements and, on occasion, fights with drivers over issues. According to Wheeler, Smith knew "he couldn't back down, because if [he] ever did, [he'd] might as well give them the keys to the place".[16] By 1955, he had managed to earn $128,050 (adjusted for inflation$, 1,456,430) in one year from promoting races throughout the Carolinas.[16]

Charlotte Motor Speedway, bankruptcy

[edit]

By the late 1950s, stock-car racing's popularity had increased dramatically in the American Southeast. With newer, more modern facilities being built, such as Darlington Raceway,[17] Smith partnered with Charlotte businessman John William Propst Jr. to plan construction of a $2 million racetrack. At the same time, Virginia stock-car racing driver and successful timber businessman Curtis Turner had begun collaborating with track officials across the Carolinas to build a speedway in northern Mecklenburg County. However, in 1958, Smith's deal with Propst fell through when Propst backed out of the partnership after suffering a heart attack, leading Smith to call Turner in hopes of his replacing Propst. After a few weeks of initial success, in a meeting at the Barringer Hotel, Turner refused to partner with Smith. Feeling betrayed and predicting that the city of Charlotte could support only one speedway, Smith proceeded to announce his intention to build a new speedway to rival Turner's. Knowing that Turner did not have enough funds to build his own speedway, compounded with the fact that Turner had struggled to sell the 300,000 shares needed for the racetrack, Smith pledged to sell 100,000 of the shares by himself and become the vice president of the speedway.[16] Construction eventually started on the speedway in the summer of 1959[18] and was eventually completed in mid-June 1960, in time for the 1960 World 600 on June 19.[19][20]

The track was plagued with numerous issues during its first race, including incomplete facilities[21] and a poor track surface.[22] Internal problems, including a lack of funds and not enough collateral supplied by both Smith and Turner, led to many creditors not being paid. Smith later called it "a miracle that the place got built", later admitting that he had lost over $150,000 constructing the track.[16][1] In 1961, grading contractor and creditor Owen Flowe forced the speedway into bankruptcy court, as he was owed $90,000 (adjusted for inflation$, 926,929). In a last-ditch effort to save the track, Smith and Turner cut a deal with the Teamsters Union (despite their mob connections) to form a union in NASCAR in exchange for the money they needed. Due to NASCAR founder Big Bill France's hard-and-fast stance against the union - famously stating "No Teamsters member will ever compete in a NASCAR race, and I'll use a pistol to enforce it" - every driver except for Turner and Tim Flock backed down; both were subsequently banned from NASCAR for life, though Turner would be reinstated in 1965.[23] Out of both money and options, the track was placed under Chapter 10 bankruptcy, ceasing all officers' and directors' positions.[24] Robert Nelson Robinson, a Charlotte lawyer who was appointed to run the speedway under bankruptcy, found that the track had amassed over $500,000 in debt and was facing a federal investigation into the initial stock sale to fund the track.[16] In that same year, facing threats of foreclosure and subsequent auction of the speedway, both Smith and Turner were ousted from the speedway's board of directors. Smith was later assigned to serve as the promotional director.[25]

In 1962, Smith was indicted over failing to properly file tax returns in 1955 and 1956.[26] He was found guilty, incurring a $4,000 fine and receiving a suspended one-year prison term in 1963.[27] As a result of his being ousted from the board of directors and his prison sentence, he left the speedway. Two years later, his name was submitted as a nomination to once again rejoin the board of directors; the nomination was met with a chorus of "boos and chants".[28]

Car dealer magnate, gradual return to Charlotte

[edit]After his failed attempt to rejoin the Charlotte Motor Speedway's board of directors, Smith decided to pursue his other dream of owning a new-car dealership. Initially joining a Ford dealership owned by Charlotte businessman Bill Beck as a salesman in 1966, he briefly moved to Colorado to run another Ford dealership owned by another Charlotte businessman, Jeff Davis. In 1968, Ford sold Smith a dealership in Rockford, Illinois. Smith was known as an extravagant spender and wealthy dealer during his time in Rockford; his business became highly successful, and he later became president of the Rockford New Car Dealers Association.[16][29] With the increasing success of his Rockford dealership, Ford offered Smith an opportunity to open a new dealership in Houston, Texas. By March 1980, after he had expanded his business to ten dealerships, he decided to either sell or close down all but two locations in Houston and Charlotte. According to Smith, the reason he decided to take this action was because of severe thunderstorms and turbulence that he experienced during a flight he had taken in 1979. Smith realized during the turbulence that he was "really working for my employees", which he no longer wanted to do. He later stated that he did not want to be tied down to a strict schedule or to be "surrounded by bureaucracy".[16]

In the mid-1970s, with the increased success and profits of his car dealerships, Smith increased his stake in the Charlotte Motor Speedway from about 40,000 in 1973 to almost 500,000 shares out of 1,884,723 total shares. He initially stated that he had no intention of owning the track again, stating that he did not know why he had bought so many shares.[30] However, he was keeping his true thoughts away from the public at the time; he had thought that owning the track would become immensely profitable after the announcement that the R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company would sponsor the NASCAR Grand National Series in 1970. By February 1974, he had managed to buy enough stock to be elected chairman of the board of directors, replacing Richard Howard, who became the president of the speedway.[28] In February 1975, Howard was threatening to resign from the board of directors, with both Howard and Smith both accusing each other of double-crossing the other, and Smith stating that he believed Howard had too much control over the speedway and had been responsible for financial irregularities.[31] By July, he bought around 80,000 shares from Howard's family and relatives.[32]

Three months later, Smith had managed to buy nearly 800,000 shares, planning to become the majority stockholder. Around this same time, rumors of Howard stepping down as president were speculated amongst the media, with Howard feeling that his position was threatened by the hiring of H. A. "Humpy" Wheeler. Tension between the two grew, with Howard being regarded as a "good ol' country boy" who wanted to spend conservatively on the track, a stark contrast to Smith, who was regarded as an affluent, extravagant businessman who had ambitions to grow the track into a world-class facility.[33] On October 5, The Atlanta Constitution reported that the 1975 National 500 was scheduled to be the final race for which Howard would be involved in the speedway, with a final decision expected to come on January 30, 1976, the day of the annual stockholders' meeting.[34] Later that same month, although Howard said that he was considering a consultant job working for Smith, he stated that he was "99% certain" that he would depart.[35] On the day of the annual stockholders' meeting, Howard made his final confirmation that he was stepping down as the president of the speedway, with Humpy Wheeler taking his position, essentially completing a takeover of control on the speedway.[36]

New investments, purchasing racetracks, and creation of Speedway Motorsports

[edit]Throughout the late 1970s and early 1980s, Smith acquired stock in numerous companies, including PCA International and Republic Bank and Trust.[37] In 1977, Smith bought a private jet from Ugandan dictator Idi Amin, who was facing severe financial and political turmoil.[38] In June 1979, Smith founded Sonic Aviation, a charter jet service company.[39] In September 1980, Smith and his previously owned companies acquired 9.99% of North Carolina Federal Savings and Loan Association, making him the largest shareholder of the company.[40] In March 1982, he sold all of his stock in Republic Bank and Trust.[37] In June of that same year, Smith sold all of his stock in PCA International to the Luxembourg-based company Minit International S.A.[41]

In the summer of 1982, he accepted a position on the board of directors at North Carolina Federal Savings and Loan Association; at that time, he owned more than 10% of the company's stock. The next year, on July 27, Smith stated his intent to file claims against every director at the company; the company had filed a lawsuit the day before, accusing Smith and his companies of illegally accumulating 54% of the company's stock.[42] After a nine-month dispute over control of the company, Smith managed to take control in the wake of the resignations of two top officials, chairman Clark Goodwin and president Kemp Causey; this took place after a Florida-based real estate development company, Roland International Corporation, proposed to acquire the savings and loan. As part of the proposed acquisition, the lawsuits were dropped.[43] However, in early May, Roland International Corporation abandoned the acquisition, essentially giving full control of the company to Smith.[44]

In 1985, Smith managed to buy all remaining stock in the Charlotte Motor Speedway, making Smith the sole owner of the track.[45] Smith began buying more racetracks in the 1990s, including the Atlanta International Raceway in 1990 for $19.8 million, saying that he would expand seating and improve other facilities.[46] After the purchase, he continued to make improvements to Charlotte Motor Speedway, adding lights in April 1992; 38,000 spectators attended the first night of practice sessions under the new lights.[47] He was later treated as an outpatient for burns on his head during a media event that promoted a "grand opening" for the new lighting system.[48] Smith also created a new division of short-track racing, named Legends Car, after feeling that the Charlotte Motor Speedway needed to cut costs for local, entry-level racing.[49] Smith later incorporated Speedway Motorsports, Inc. (SMI) in 1994,[50] offering 4.5 million shares during the first business quarter in 1995 at a price of $18 per share.[51] The stock price of SMI saw immediate growth, almost tripling in price from 1995 to 1999, approximately matching the performance of the US stock market during that period.[52] Using stock profits from the company, he began construction of a new track in northern Fort Worth, Texas, promoting the Vice President of Personal Relations at Charlotte Motor Speedway, Eddie Gossage, to head the track.[53] Smith and businessman Bob Bahre bought the North Wilkesboro Speedway in the winter of 1995, with each having half of the speedway's control.[54] Later in the decade, Smith bought the Bristol International Raceway[55] and the Sears Point Raceway in 1996,[56] and the Las Vegas Motor Speedway in 1998.[57]

Sonic Automotive

[edit]In February 1997, Smith incorporated Sonic Automotive, a car dealership business. In August of that same year, Smith decided to take the company public at the New York Stock Exchange, hoping to raise $104 million (adjusted for inflation$, 197,393,035). At the time, Sonic Automotive had 20 dealerships, including the two that Smith had kept during his early days as a car dealership owner. The decision to go public was seen as "puzzling" by industry experts, as industry trends had shown a downward trend for public car dealership companies at the time.[58] By the end of the year, Smith had bought new dealerships in Atlanta, Georgia, and Fort Mill and Rock Hill, South Carolina.[59] Smith's stated goal was to create an "auto mall", where numerous car dealerships would offer cars from multiple manufacturers near a flagship site. The decision was seen by members of the industry as a decision that followed recent trends toward consolidation, with big companies buying out individual car dealerships.[60]

Throughout the late 1990s and the entirety of the 2000s, the company saw continuous growth, eventually becoming a Fortune 500 company in 2000. In 2002, Smith was rumored to be retiring from the company after an announcement of a successorship plan made by his son Scott. The older Smith told The Charlotte Observer, "I'm not going to retire, period. We have no successorship plan." William Belk, a member of the company's board of directors, later clarified the statement made by Scott, stating that "he was probably forecasting 20 years down the road, not the next year or two."[61]

Later business ventures

[edit]Smith continued buying speedways throughout the 2000s, including both the New Hampshire International Speedway[62] and the Kentucky Speedway in 2008.[63] He also acquired full control of the North Wilkesboro Speedway from Bob Bahre in 2007.[64]

In an attempt to coerce NASCAR into building the newly announced NASCAR Hall of Fame in Charlotte, he pledged $50 million toward a Lynx Rapid Transit Services light-rail line that would have connected the Charlotte Motor Speedway to uptown Charlotte, while also passing near the original Charlotte Speedway.[65] However, the city of Charlotte ultimately found the monorail infeasible due to high costs and the plan being dependent on the monorail's extension towards the Charlotte Motor Speedway.[66][67]

In 2019, Smith took Speedway Motorsports private and took the company off the NYSE; the Sonic Financial Corporation, another company Smith owned, acquired all outstanding shares of SMI.[68] According to Hendrick Motorsports' founder and owner Rick Hendrick, Smith was still active as a businessman up until his death. Smith, according to Hendrick, had tried to advocate the usage of zMax, a micro-lubricant which had sponsorship rights on the Charlotte Motor Speedway dragstrip, on all of Hendrick's cars, despite the fact that Smith was immobile.[69]

Legal issues and controversies

[edit]Smith was involved in numerous business and legal battles since his start as a businessman.

Legal battles

[edit]Since the construction of Charlotte Motor Speedway, Smith faced financial difficulties and lawsuits filed against him. In 1962, Smith was indicted for failing to properly file tax returns in 1955 and 1956, later being found guilty in 1964.[26] He later blamed a neighbor he had hired to do his taxes, stating that "I'd paid my tax. I didn't owe the government a damn dime."[2] In December 1985, Smith was sued by 21 former stockholders of the Charlotte Motor Speedway, accusing Smith of both unfairly removing 640 minority stockholders from the speedway and paying the stockholders an unfairly low price for the stock after Charlotte Motor Speedway, Inc., merged with Lone Star Ford earlier that year.[70] After a U.S. District judge ruled that any of the 640 former stockholders could join the lawsuit in June 1986,[71] he settled the lawsuit in December, paying $1.9 million to the former stockholders.[72]

In 1997, Smith entered a bidding war with Roger Penske over the purchase of the North Carolina Motor Speedway (now known as Rockingham Speedway). In early April, Penske and his company, Penske Motorsports, who had owned 4.5% of the speedway at the time, offered to buy the speedway for $29.4 million. In response, Smith, who owned about 25% of the speedway, offered $48.3 million.[73] By April 16, Smith raised his offer to almost $72 million. Carrie DeWitt, the track's majority shareholder who owned about 65%, rejected Smith's offer, on the basis that she feared the track would undergo the same fate as of a neighboring track, North Wilkesboro Speedway, which was left abandoned and desolate after both Smith and businessman Bob Bahre bought the track in 1995.[74] The track was eventually bought by Penske Motorsports. In response, Smith, along with 15 other shareholders, filed a lawsuit against Penske in the North Carolina Supreme Court, asking Penske to pay him $50 per share for his stock, or $17.7 million total.[75] The lawsuit was heard and decided in April 2000. The court determined the stock to be worth $23.47 per share and awarded Smith more than $3.6 million, a decision that was viewed positively by Penske.[76]

In 2005, Richard Duchossios, one of the former owners of the Kentucky Speedway, sued NASCAR in an antitrust lawsuit, claiming that both NASCAR and the International Speedway Corporation had an unfair monopoly over the sport. When Speedway Motorsports bought the speedway in 2008, according to Duchossios, he offered to sell the lawsuit to Smith. The case was dismissed in 2008.[77] In December 2009, an appeal was rejected.[78]

In 2010, Smith sued Las Vegas entertainer Wayne Newton, claiming that Newton was delinquent on a loan he had personally guaranteed, then bought from Bank of America. Along with the loan, Smith sought foreclosure on Casa de Shenandoah, Newton's ranch.[79] According to Smith, Newton had promised to cover the loan from Bank of America and to secure the loan using his house and a $2 million jet.[80] In July of that year, the case was voluntarily dismissed.[81]

North Carolina Federal Savings and Loan Association

[edit]In June 1983, one year after he was elected to the board of directors of the North Carolina Federal Savings and Loan Association, the company sued Smith, claiming that Smith and his companies had illegally accumulated 54% of the company's stock in an attempted takeover. The next day, Smith stated his intent to file claims against every director at the company, calling the lawsuit "ridiculous".[42] After a company meeting on August 1 that approved a proposed merger with four smaller S&Ls, Smith's close associate Humpy Wheeler called the top management of the company "absolute liars". Smith, who opposed the merger, stopped further negotiations with the company's management.[82] The merger voting results were later invalidated, with a new vote scheduled to take place on August 19.[83] The company's board of directors later published a letter in The Charlotte Observer, stating that Smith had agreed to the merger and that the company did not feel that it was appropriate to hand over control of the company to Smith. The letter also stated that the lawsuit was to ensure Smith complied with the merger.[84] Three days later, Smith sold 9.08% of the company's stock to Fort Worth real estate developer Herman Smith.[85]

One of the four S&Ls that was proposed to be acquired by North Carolina Federal, Perpetual Savings and Loan, backed out of being acquired by North Carolina Federal and instead opted to be acquired by Providence, Rhode Island–based Old Stone Corporation in September, a decision that was seen as a surprise by both sides.[86] On September 7, a minority shareholder of the company, Bill Smith, sued the company's board of directors, seeking a reimbursement of $10.4 million for losses that Bill Smith alleged the company caused. While Bruton Smith had not been apprised of the lawsuit, he stated that he was willing to testify in its support.[87]

A decision on the July 26 lawsuit from the Federal Home Loan Bank Board was expected in early September. However, the decision was stalled for months.[88] On December 21, Smith announced an agreement with the bank board. In January 1984, the Federal Home Loan Bank Board bowed out of the dispute, issuing orders for Smith to cease and desist violations of several federal securities acts and regulations.[89] As a result, both sides nominated opposing slates for the seven-person board of directors. On January 10, another S&L that was to be acquired by North Carolina Federal, North Wilkesboro Federal, sued both Smith and the company for $13.6 million, claiming that North Wilkesboro Federal was the victim of breach of contract.[90] Nine days later, Florida-based real estate company Roland International announced its intention to buy out North Carolina Federal, expecting a deal within three weeks.[91] In early March, a compromise slate of seven directors was proposed to be elected on March 30.[92] On the day of the board of directors election, the board's top two directors, former chairman Clark Goodwin and president Kemp Causey, resigned, with the company electing Graham Harwood as president.[43] In early May, the acquisition by Roland International was abandoned, essentially giving full control of the company to Smith.[44]

Smith continued to be the company's majority shareholder, with Harwood as president, presiding over a quick rebound of annual losses by 1986. In that same year, the company returned to compliance with federal capital rules for the first time since 1982.[93] In 1985, North Carolina Federal financed Piper Glen, a golf-oriented community, for $17 million. After four years, Piper Glen did not earn a return, leading to the stock price of the company plummeting from over $10 to "about $2" within the span of a week, making the company lose $1.7 million annually.[94] The failure of Piper Glen, along with numerous other problems with real estate ventures and bad loans to apartment developers, caused North Carolina Federal to lose $29.4 million in 15 months. As a result, the Resolution Trust Corporation seized North Carolina Federal on March 2, 1990, effectively wiping out the company and replacing it with the North Carolina Savings and Loans Association. Resolution Trust bailed out the company for $11 million. As a result of the seizure, Smith lost around $4 million, which he said he could absorb.[95]

Reaction to Lowe's Motor Speedway dragstrip opposition

[edit]

On August 31, 2007, The Observer reported that Smith had confirmed his interest in building a dragstrip at Lowe's Motor Speedway (now called Charlotte Motor Speedway) to host National Hot Rod Association (NHRA) events.[96] By late September of that year, however, the Concord City Council had called for a special session to potentially block Smith's plans, with concerns including the noise level, pollution, and fumes affecting local residents and businesses in the Concord area.[97] Smith vehemently disagreed with the session, stating that he wished that the speedway had never been annexed into Concord, and deciding to start preliminary grading on the dragstrip location regardless of the session's decision.[98] The Concord City Council unanimously ruled on October 2 that construction on the drag strip must halt, with the city changing the zoning around the track.[99] The next day, Smith demanded that the speedway and its surrounding land be unannexed from the city of Concord or he would shut down the speedway and either demolish the speedway or relegate the speedway to a testing facility, taking hundreds of millions of dollars away from the Concord economy.[100]

On October 9, the Concord City Council reversed its stance on the dragstrip with a 5–1 vote, with only councilman Randy Grimes retaining his original vote. In response, Smith called Grimes an "enemy of the speedway" and maintained that he had not made a final decision on whether to move the speedway.[101] In an attempt to convince Smith to let the speedway stay in Concord, both the Concord City Council and the Cabarrus County Board of Commissioners offered a tax break, a street near the speedway to be named after Smith, and an incentive package worth approximately $80 million.[102] On November 26, Smith stated his final decision to let the speedway stay in Concord, stating, "We're here forever." Along with the statement, Smith announced scheduled NHRA events.[103]

Smith's actions regarding the speedway were widely viewed as negative by citizens of Concord and its county, Cabarrus County. Many within the area felt that Smith had used his wealth and power to massively exploit the city of Concord for tens of millions of dollars. With the city having experienced numerous major industries either being outsourced or shut down, citizens felt Smith had used the tenuous economic situation of Concord to gain the $80 million incentive package and essentially crush the citizens' concerns. The Observer editorial board wrote, "We predicted a couple of months ago that the Concord residents would find their victory against Mr. Smith short-lived. It was indeed."[104]

The dispute was reopened in September 2009, when Smith sued Cabarrus County and the city of Concord for $4 million, demanding quicker payment of funds for roadwork. Smith claimed that the $4 million was part of the $80 million incentive package. In addition, no formal timetable for payment of the incentive package was ever set. Smith claimed that he believed that the payment was to be reimbursed within nine years, while the city of Concord said that the payment would be made within 40 years.[105] The lawsuit was dropped on June 1, 2010, without prejudice, in hopes that Smith and the city of Concord could settle the case out of court.[106] On May 27, 2011, Smith refiled the lawsuit.[107] The lawsuit was partly settled on June 29, with the city of Concord agreeing to pay $2.8 million for roadwork.[108] In March 2012, the lawsuit was dismissed by the Cabarrus County Superior Court.[109] Smith made attempts to resurrect the lawsuit in 2013, claiming that the city of Concord had backed out of the incentive package.[110] The lawsuit was again dismissed, with the North Carolina Court of Appeals stating that Smith and the city of Concord did not have a formal contract.[111] After taking the case to the North Carolina Supreme Court, Smith lost the case on December 19, ending over seven years of conflict between Smith and the city of Concord.[112]

Personal life

[edit]Marriage and divorce

[edit]Smith married Bonnie Jean Harris on June 6, 1972, in North Las Vegas, Nevada. Smith had met Harris in 1969 while selling her a Ford Thunderbird in Illinois. Bruton and Bonnie had five children together: Anna Lisa, Bruton Jr., David, Marcus, and Scott.[113] Four were still living when their father died; Bruton Smith Jr. died when he was seven months old in a crib accident in 1980.[15]

After Bruton Smith Jr.'s death, the marriage deteriorated, with one of their children, Scott, stating that the death "really wiped [Bonnie] out pretty badly, and somewhere in there is when their marriage really began to go south".[16] Bonnie filed for divorce in July 1988 after a June 24 argument in which Bruton was stated to have gone into "a rage", grabbing a fire poker and proceeding to tear down a portrait of her, according to court records.[45] Bonnie also claimed that later that day, Bruton threatened her with a butcher knife, repeatedly threatening her with physical harm if she began legal proceedings against him. In response to the allegations made by Bonnie, Bruton filed a court document in August 1988, in which while he admitted to destroying the portrait but denied all other allegations. In addition, he accused his wife of adultery, stating that he believed that Bonnie was not fit to have custody of his four living children. In November of that year, Bruton agreed to pay $6,000 a month in child support along with paying up to $300,000 (adjusted for inflation$, 772,876) for a new home for Bonnie, and up to $50,000 to furnish the home.[114]

In 1990, a trial was ordered to determine the value of the marital property of the Smiths under the orders of Mecklenburg County District Judge L. Stanley Brown. The case would also determine how the marital property would be divided between the two. On April 6, 1991, The Charlotte Observer reported that the marital property was worth $51.3 million (adjusted for inflation$, 132,161,733); Bruton was ordered to pay $21 million to Bonnie, the largest divorce judgment in North Carolina history.[115] Bruton later appealed that same year to lower the divorce award,[116] after his requests to lower the award were declined by Brown.[117] The case was heard in numerous courts, including the North Carolina Supreme Court and the North Carolina Court of Appeals. In fall 1994, Bruton agreed to pay a settlement of $19.4 million, which included a provision to pay Bonnie's attorney's fees of around $2 million.[118] As part of the settlement, Bruton agreed to pay about $445,000 to Bonnie's law firm, Robinson Bradshaw & Henson.[119] As a response, Robinson Bradshaw & Henson sued Bruton for not fully paying the fee, with Bruton proceeding to countersue, stating that Bonnie's lawyer, Martin Brackett, had an extramarital affair with Bonnie.[16] Bruton lost the case, with Bruton being ordered to pay over $1.5 million in attorney's fees, a fee that he would not pay in full until 2001.[2]

Religious views

[edit]Smith was an evangelical Christian, reportedly having found religion late in life.[69] Smith was on the board of directors of the PTL Satellite Network, an evangelical Christian television network that was based in the Carolinas.[120]

Philanthropy

[edit]Smith created Speedway Children's Charities in 1982 after one of his children, Bruton Smith Jr., died at seven months old in 1980. As of June 2022, the charity had donated more than $61 million to child-related causes.[3]

Wealth

[edit]Smith had been placed into the Forbes 400 list starting in 2005, listed as the 207th richest American with a net worth of approximately $1.5 billion (adjusted for inflation$, 2,340,092,009). He fell off the list in 2009, with his last estimated net worth being $1.2 billion in 2008.[121]

Illness and death

[edit]In June 2015, Smith was diagnosed with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.[122] In the summer of that year, he received surgery to treat the disease; the surgery was successful.[123]

Smith died on June 22, 2022, in Charlotte, North Carolina, at the age of 95 due to natural causes.[13] A public funeral service was held on June 30 at the Central Church of God in Charlotte, with a private burial service following the funeral service.[124]

Legacy and honors

[edit]

Smith was considered to be one of the most influential businessmen in both the auto racing and automotive sales industries by industry leaders and the media. Humpy Wheeler, the former president of Charlotte Motor Speedway, described Smith as "a force to be reckoned with ... when he wanted something, he got it, just from pure perseverance, despite a lot of animosity from NASCAR".[125] Former Texas Motor Speedway president Eddie Gossage stated that Smith was "the greatest boss ever", stating that he had managed to turn several racetracks across the United States into world-class facilities comparable to Charlotte Motor Speedway, the first track Smith owned.[126] Chris Powell, current president of the Las Vegas Motor Speedway, praised Smith's work ethic, calling him a "visionary .... He yearned every day to work. His idea of going on vacation was going out of town to work".[127] Smith was also known to possess a mysterious persona. The Charlotte Observer writer Dick Stilley called Smith "a mystery even to his friends" in a 1982 article that referenced many industry leaders' thoughts about Smith.[15]

Speedway Motorsports – International Speedway Corporation rivalry

[edit]![A photo overlooking the third and fourth turns of the [[Texas Motor Speedway]] taken in 2017.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/60/2017_Rainguard_Water_Sealers_600_01.jpg/220px-2017_Rainguard_Water_Sealers_600_01.jpg)

Smith's rivalry with the France family led to increasing tensions between their respective companies, Speedway Motorsports and the International Speedway Corporation (ISC). Before NASCAR's acquisition of ISC, the two companies competed for race weekends. Stockholders of both companies sued each other, culminating in the Ferko lawsuit, which resulted in numerous schedule changes that have had a lasting effect on NASCAR's legacy and popularity.[128] Before the settlement of the Ferko lawsuit was announced, Smith's desire for a second NASCAR Cup Series race at Texas Motor Speedway led to longstanding rumors that Smith would split off from NASCAR to form his own racing series.[129]

By 2016, however, the NASCAR Hall of Fame had elected Smith and his partner in creating Charlotte Motor Speedway, Curtis Turner, with then-CEO of NASCAR Brian France stating that he liked Smith "very much."[129] The election was seen as a move toward a period of détente between the two families, as in past years, Smith had not been elected into the Hall of Fame despite leading polls.[129][130]

Recognition

[edit]- Smith was inducted in the North Carolina Business Hall of Fame in 2006.[131]

- He was inducted by the National Motorsports Press Association to the Stock Car Racing Hall of Fame in 2006.[132]

- In 2008, the city of Concord renamed Speedway Boulevard off Interstate 85 to "Bruton Smith Boulevard".[133]

- He was inducted in the International Motorsports Hall of Fame in 2007.[134]

- Smith was inducted into the NASCAR Hall of Fame on January 23, 2016.[135]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Kennedy, John W. (October 7, 1979). "Concord's Smith Helped Build Charlotte Speedway". Rocky Mount Telegram. p. 39. Archived from the original on July 4, 2023. Retrieved July 4, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e Zeller, Bob (July 1, 2003). "Bruton and the Two Bills: A 50-Year Rivalry". Car and Driver. Archived from the original on July 4, 2023. Retrieved July 4, 2023.

- ^ a b Fowler, Scott (June 25, 2022). "NASCAR's Smith had one-of-a-kind life, legacy". Lexington Herald-Leader. pp. 6A, 11A. Archived from the original on July 4, 2023. Retrieved July 4, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Fowler, Scott (October 13, 2010). "20 Questions With Bruton Smith". The Charlotte Observer. p. 7C. Retrieved July 17, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Davison, John (May 6, 2005). "Bruton Smith on Racing's Past, Present & Future". FastMachines. Archived from the original on February 6, 2008. Retrieved July 4, 2023.

- ^ "Bruton Smith Named Head". The Charlotte News. November 30, 1957. p. 5A. Archived from the original on July 4, 2023. Retrieved July 4, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Oakboro native, NASCAR pioneer Bruton Smith dies". The Stanly News and Press. June 22, 2022. Archived from the original on July 4, 2023. Retrieved July 4, 2023.

- ^ Hagerty, James R. (July 1, 2022). "Speedway Owner Added Touches of Luxury to a Noisy Sport". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ^ Hembree, Mike (June 22, 2022). "NASCAR Hall of Fame pioneer, promotor Bruton Smith dies at 95". USA Today. Archived from the original on July 4, 2023. Retrieved July 4, 2023.

- ^ Kirby, Gordon (June 18, 2009). "The first 'Strictly Stock' race". Motor Sport. Archived from the original on July 4, 2023. Retrieved July 4, 2023.

- ^ Zier, Patrick (November 4, 2003). "France Family Faced Competition and Won Gracefully". The Ledger. Archived from the original on July 4, 2023. Retrieved July 4, 2023.

- ^ Jones, Anne B.; White, Rex (March 18, 2015). All Around the Track: Oral Histories of Drivers, Mechanics, Officials, Owners, Journalists and Others in Motorsports Past and Present. McFarland. p. 44. ISBN 9780786482436. Archived from the original on July 16, 2023. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ^ a b Scott, David (June 30, 2022). "Charlotte Motor Speedway founder dies at 95". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1G, 2G. Retrieved November 12, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Samples, Eddie (March 26, 2010). "The Rise and Fall of the NSCRA". Georgia Racing History. Archived from the original on July 7, 2023. Retrieved July 7, 2023.

- ^ a b c Stilley, Dick (May 24, 1982). "Behind Bruton's Poker Face". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1D, 4D, 5D. Archived from the original on July 9, 2023. Retrieved July 5, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Mildenburg, David (October 1, 1995). "Risk At Every Turn". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1A, 14A, 15A. Archived from the original on July 16, 2023. Retrieved July 4, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Poole, David; St. Onge, Peter (May 24, 2009). "A wild ride for everybody". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 13C, 14C, 15C. Retrieved July 17, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hickman, Herman (December 25, 1959). "Turner Visits New Track Site". Winston-Salem Journal. p. 19. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 7, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Cunningham, George (June 15, 1960). "Are Stock Drivers Honest?". The Charlotte Observer. p. 8C. Archived from the original on July 16, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Muhleman, Max (June 20, 1960). "The Show Won't Be Forgotten". The Charlotte News. p. 2B. Retrieved November 12, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Talbert, Bob (June 15, 1960). "'600' Officials Take Issue". The State. p. 4B. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 7, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Burrell, Frank (June 20, 1960). "Joe Lee Johnson Wins World 600". The Herald. p. 5. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 7, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "NASCAR and labor unions: A tumultuous history". FOX Sports. Retrieved November 7, 2024.

- ^ Martin, Gerald (February 2, 1976). "Track's New Owner Has Costly Dream". The News & Observer. p. 18. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 7, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Murleman, Max (June 9, 1961). "Foreclosure Threat Led To Quittings". The Charlotte News. p. 2B. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 7, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Bruton Smith Indicted For Failure To File Taxes". Asheville Citizen-Times. Associated Press. March 2, 1962. p. 17. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 7, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Wildman, John (November 28, 1990). "Smith Rode Love Of Cars To The Top". The Charlotte Observer. p. 10A. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 7, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Covington, Roy (February 3, 1974). "After 9 Years, The Boos Changed To Votes". The Charlotte Observer. p. 6D. Archived from the original on July 7, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Kenneth, Ross (April 5, 1971). "Tho Hard Hit, Rockford Confident It Will Regain Economic Vitality". Chicago Tribune. pp. 1, 8. Archived from the original on July 16, 2023. Retrieved July 5, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Myers, Bob (May 26, 1973). "Bruton Smith's Return". The Charlotte News. p. 9A. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Myers, Bob (February 1, 1975). "The Speedway Shootout". The Charlotte News. pp. 7A, 8A. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Covington, Roy (October 12, 1975). "Bruton Smith Simply Outran Speedway's Richard Howard". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 9B. Retrieved February 4, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Myers, Bob (October 8, 1975). "Track Needs Howard". The Charlotte News. pp. 1C, 4C. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hunter, Jim (October 5, 1975). "National 500 Race Last for Howard?". The Atlanta Constitution. p. 10D. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Mulhurn, Mike (October 23, 1975). "Car Builders May Challenge France's Rule". Winston-Salem Journal. p. 53. Archived from the original on July 7, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Myers, Bob (January 31, 1976). "Wheeler: Speedway's New Dealer". The Charlotte News. p. 1B. Archived from the original on July 9, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Stilley, Dick (May 9, 1982). "What's Bruton Smith Up To With Republic, PCA Deals?". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 5B, 6B. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Kelley, Pam (July 28, 1983). "Smith a farm boy with Midas touch". The Charlotte News. pp. 1A, 3A. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Smith Opens Charter Jet Service". The Charlotte Observer. June 24, 1979. p. 9B. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Stilley, Dick (September 12, 1980). "Car Dealer Acquires Almost 10% Share of N.C. Federal". The Charlotte Observer. p. 4B. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Stilley, Dick (June 4, 1982). "Bruton Smith Sells Stock In PCA, Realizes $250,000". The Charlotte Observer. p. 14A. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Mildenberg, David (July 28, 1983). "N.C. Federal suit shatters genial alliance". The Charlotte News. pp. 1A, 3A. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Ellis, Marion A. (March 31, 1984). "N.C. Federal Changing Leadership". The Charlotte Observer. p. 12A. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Fletman, Abbe (May 4, 1984). "Smith in 'complete control' as S&L buyout collapses". The Charlotte News. p. 14A. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Zeller, Bob (October 13, 1991). "Speedway owner lives in fast lane". News & Record. pp. C1, C2. Archived from the original on July 4, 2023. Retrieved July 4, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Higgins, Tom (October 24, 1990). "Smith Buys Atlanta Raceway". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1C, 2C. Archived from the original on July 9, 2023. Retrieved July 8, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Higgins, Tom (April 17, 1992). "Wallace fastest as 27,500 watch night practice". The Charlotte Observer. p. 5B. Archived from the original on July 9, 2023. Retrieved July 8, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Higgins, Tom (April 16, 1992). "Speedway test is ablaze in glory". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1B, 2B. Archived from the original on July 9, 2023. Retrieved July 8, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Racing Redefined - Making Legends: History of Legend Racing". NBC SportsEngine. August 12, 2021. Archived from the original on July 9, 2023. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ Vonder Haar, Steven (December 24, 1994). "Racetrack developer to sell stock shares". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. p. C2. Archived from the original on July 9, 2023. Retrieved July 8, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Reeves, Scott (February 22, 1995). "Speedway plans to go public". The News & Observer. pp. 1D, 2D. Archived from the original on July 9, 2023. Retrieved July 8, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "S&P 500 Returns since 1995".

- ^ Martin, Roland S. (April 12, 1995). "Speedway is off to a bang-up start". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. pp. A1, A15. Archived from the original on July 9, 2023. Retrieved July 8, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Mulhurn, Mike (July 14, 1996). "BAHRE MARKET: Owner explains North Wilkesboro transaction". Winston-Salem Journal. pp. 1C, 8C. Retrieved November 12, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hembree, Mike (January 23, 1996). "Charlotte's Smith buys Bristol Raceway". The Greenville News. p. 4C. Archived from the original on July 9, 2023. Retrieved July 8, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Leef, Ralph (November 14, 1996). "Planning begins for Sears Point improvements". The Press Democrat. pp. C1, C3. Archived from the original on July 9, 2023. Retrieved July 8, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Thompson, Gary (December 21, 1998). "Las Vegas speedway buy a good deal". Tri-City Herald. Las Vegas Sun. p. 20. Archived from the original on July 9, 2023. Retrieved July 8, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Moore, Pamela L. (August 19, 1997). "Sonic is going public". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1D, 2D. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Kempner, Matt (December 20, 1997). "Another big auto dealer entering Atlanta market". The Atlanta Constitution. p. D1. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Milstead, David (August 31, 1997). "Dealing dealerships". The Herald. pp. 1A, 10A. Archived from the original on July 7, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Dyer, Leigh (November 27, 2002). "Smith: 'I'm not going to retire'". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1D, 6D. Archived from the original on July 7, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ D'Onofrio, Dave (November 2, 2007). "Reports: Speedway sold". Concord Monitor. pp. A1, A6. Archived from the original on July 9, 2023. Retrieved July 8, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Amick, Adam (May 27, 2008). "Bruton Smith Buys Kentucky Speedway – Is Dover In His Deck?". Bleacher Report. Archived from the original on July 9, 2023. Retrieved July 9, 2023.

- ^ Vega, Michael (November 3, 2007). "Price for N.H. oval: $340m". The Boston Globe. p. C8. Retrieved November 11, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Fryer, Jenna (May 24, 2005). "Smith proposes monorail in N.C. Hall of Fame push". USA Today. Archived from the original on July 19, 2008. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ Whitacre, Dianne (June 3, 2005). "Smith's millions may help rail go". The Charlotte Observer. p. 4B. Retrieved November 12, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Cimino, Karen (June 28, 2006). "For light rail, is I-485 a bridge too far?". The Atlanta Journal. p. 3B. Retrieved November 12, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ McFadin, Daniel (September 17, 2019). "Speedway Motorsports, Inc. becomes privately owned". NBC Sports. Archived from the original on July 9, 2023. Retrieved July 9, 2023.

- ^ a b Fowler, Scott (July 1, 2022). "NASCAR pioneer's memorial showcases power of imagination". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1B, 2B. Archived from the original on July 16, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Kelley, Pam (December 20, 1985). "Speedway Stock Deal Disputed". The Charlotte Observer. p. 1B. Retrieved November 13, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Mildenberg, David (July 17, 1986). "Former Stockholders Can Join Speedway Lawsuit, Judge Rules". The Charlotte Observer. p. 5C. Retrieved November 13, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Court Accepts Speedway Suits Settlement". The Charlotte Observer. December 25, 1986. p. 4B. Archived from the original on July 9, 2023. Retrieved July 8, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Mulhurn, Mike (April 4, 1997). "Dealmakers: Smith, Penske want Rockingham". Winston-Salem Journal. pp. C1, C5. Retrieved July 17, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Whitehead, Bill (October 23, 1997). "Battle for the biggest piece of the 'Rock'". St. Lucie News Tribune. p. C7. Retrieved July 17, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Ward, Leah Beth (March 22, 1998). "Battling for a piece of 'the Rock'". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1D, 8D. Retrieved July 17, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Wright, Gary L. (April 26, 2000). "Smith awarded $3.6 million in speedway suit". The Charlotte Observer. p. 4B. Retrieved July 17, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Former Speedway owners not giving up lawsuit". The Augusta Chronicle. May 15, 2009. Archived from the original on July 9, 2023. Retrieved July 9, 2023.

- ^ Barrouquere, Brett (December 11, 2009). "Court rejects Ky. Speedway lawsuit against NASCAR". San Diego Union-Tribune. Archived from the original on July 9, 2023. Retrieved July 9, 2023.

- ^ "Former friend seeks to foreclose on singer Wayne Newton's home". Las Vegas Sun. February 17, 2010. Archived from the original on April 18, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ^ Divito, Nick (February 12, 2010). "Wayne Newton Defaulted on $3M, NASCAR Big Says". Courthouse News Service. Archived from the original on October 4, 2022. Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ^ Schoenmann, Joe (September 1, 2010). "Wayne Newton wants to show off home, private jet, too". Las Vegas Sun. Archived from the original on May 3, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ^ Mildenberg, David (August 2, 1983). "N.C. Federal–Smith feud builds, erupts into name-calling". The Charlotte News. p. 6A. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Mildenberg, David (August 10, 1983). "N.C. Federal merger vote thrown out". The Charlotte News. p. 10A. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "An Open Letter To The Stockholders And Depositors Of North Carolina Federal Savings And Loan Association". The Charlotte Observer. August 15, 1983. p. 10B. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Stilley, Dick (August 18, 1983). "Smith Sells 9% Off S&L To Texas Man". The Charlotte Observer. p. 13A. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Mildenberg, David (September 8, 1983). "Emergency Perpetual S&L merger adds twist to N.C. Federal battle". The Charlotte News. p. 10A. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Ellis, Marion A. (September 8, 1983). "Shareholder Sues S&L Board For $10 Million". The Charlotte Observer. p. 4B. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Mildenberg, David (December 2, 1983). "N.C. Federal's Fees And Losses Accumulating". The Charlotte Observer. p. 8C. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Fletman, Abbe (January 7, 1984). "Bank Board Ends Its Role In Charlotte S&L Dispute". The Charlotte Observer. p. 13A. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "N. Wilkesboro S&L Suing N.C. Federal Over Failed Merger". The Charlotte Observer. Associated Press. January 11, 1984. p. 14A. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Mildenberg, David (January 20, 1984). "S&L buyer sees deal in 3 weeks". The Charlotte Observer. p. 6A. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Mildenberg, David (March 13, 1984). "N.C. Federal S&L, Businessman Smith Nominate Directors". The Charlotte Observer. p. 4D. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Matthews, Steve (January 6, 1986). "S&L Has Sharp Turnaround". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1B, 9B. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Matthew, Steve (May 15, 1989). "Piper Glen's Woes Drag N.C. Federal Into Rough". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1C, 8C, 9C. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ McIntosh, Jay (March 3, 1990). "Regulators Seize N.C. Federal S&L". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1A, 7A. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Bell, Adam; Poole, David (August 31, 2007). "LMS considering adding drag strip". The Charlotte Observer. p. 10C. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Durhams, Sharif (September 27, 2007). "Concord hitting brakes on drag strip plan?". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1B, 6B. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Durhams, Sharif (September 29, 2007). "Work continues at drag strip site". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1B, 6B. Archived from the original on July 7, 2023. Retrieved July 7, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Durhams, Sharif (October 2, 2007). "Council orders halt to work on drag strip". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1B, 2B. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 7, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Durhams, Sharif; Poole, David (October 3, 2007). "Smith: My way or no speedway". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1A, 16A. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 7, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Cherrie, Victoria (October 13, 2007). "Governor's office said to be helping woo Smith (Part 1)". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1B, 2B. Archived from the original on July 7, 2023. Retrieved July 7, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Durhams, Sharif (October 25, 2007). "Where the street has his name?". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1A, 14A. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 7, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ George, Jefferson; Bell, Adam (November 27, 2007). "'We're here forever.'". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1A, 9A. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 7, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Speedway saga". The Charlotte Observer. November 28, 2007. p. 14A. Archived from the original on July 7, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ St. Onge, Peter (September 18, 2009). "Speedway sues Cabarrus and Concord". The Charlotte Observer. p. 2B. Retrieved July 17, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Valle, Kirsten (June 2, 2010). "Speedway drops lawsuit against Concord, Cabarrus County". The Charlotte Observer. p. 9A. Retrieved July 17, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Cooke, Megan (June 16, 2011). "Speedway refiles lawsuit against Concord, Cabarrus". The Charlotte Observer. p. 1B. Retrieved July 17, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Bell, Adam (June 30, 2011). "Concord and speedway settle long-running dispute". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1B, 4B. Retrieved July 17, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Johnson, Lukas (March 18, 2012). "Judge dismisses speedway's lawsuit". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1K, 6K. Retrieved July 17, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "$80M speedway lawsuit's fate up to Court of Appeals". News & Record. Associated Press. August 29, 1988. p. B10. Retrieved July 17, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "NC high court hears speedway's suit over $80M deal". WBTV. Associated Press. September 9, 2014. Retrieved July 18, 2023.

- ^ Gordon, Michael (December 25, 2014). "Bruton Smith loses legal battle vs. Cabarrus". The Charlotte Observer. p. 6A. Retrieved July 17, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Bonkowski, Jerry (June 22, 2022). "Breaking News: Legendary motorsports entrepreneur O. Bruton Smith passes away at 95". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on July 4, 2023. Retrieved July 4, 2023.

- ^ Morell, Ricki; Wright, Gary L. (November 28, 1990). "Wealthy Couple's Divorce Turns Bitter". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1A, 10A. Archived from the original on July 4, 2023. Retrieved July 4, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Wright, Gary L.; Renn, Joseph (April 6, 1991). "Speedway owner's divorce settlement: $21 million". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1A, 7A. Archived from the original on July 4, 2023. Retrieved July 4, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jim, Schlosser (June 18, 1991). "Appeals court becoming more like 'Divorce Court'". News & Record. p. 1B. Archived from the original on July 4, 2023. Retrieved July 4, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Menn, Joesph (June 11, 1991). "2 motions pending in divorce case". The Charlotte Observer. p. 2D. Archived from the original on July 4, 2023. Retrieved July 4, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Stancill, Nancy (December 7, 1994). "Smith property-division case settled". The Charlotte Observer. p. 30. Archived from the original on July 4, 2023. Retrieved July 4, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Sullivan, Kristin N.; Nix, Mede (May 14, 1995). "Texas track may culminate developer's career". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. pp. A1, A21. Archived from the original on July 4, 2023. Retrieved July 4, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Ministers, Businessmen, Actors Help PTL Management Team". The Charlotte Observer. August 31, 1980. p. 163. Archived from the original on July 16, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Murdock comes down a few notches on Forbes list". Salisbury Post. March 13, 2009. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ Utter, Jim (August 22, 2015). "Bruton Smith returns to track after battle with cancer". Motorsport.com. Archived from the original on July 7, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023.

- ^ "Speedway Motorsports owner Bruton Smith treated for non-Hodgkin's lymphoma". USA Today. Associated Press. August 21, 2015. Archived from the original on July 7, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023.

- ^ Williams, Ellis (July 1, 2022). "'Look at all he built.' Bruton Smith funeral draws hundreds". The Charlotte Observer. p. 10A. Archived from the original on July 16, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Zietlow, Alex (May 28, 2023). "Wheeler discusses Smith, rainy Coca-Cola 600s, more". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1B, 13B. Archived from the original on July 7, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Stern, Adam (June 27, 2022). "Closing Shot: 'He set the standard'". Sports Business Journal. Archived from the original on July 7, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023.

- ^ Kantowski, Ron (June 22, 2022). "LVMS owner Bruton Smith dies at age 95". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 7, 2023.

- ^ Wilson, Jeff (November 2, 2005). "Fan wishes he hadn't filed suit". ThatsRacin. The Charlotte Observer. Archived from the original on July 8, 2006. Retrieved July 7, 2023.

- ^ a b c Fowler, Scott (May 21, 2015). "Bruton Smith draws honors from NASCAR". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1B, 6B. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 7, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Long, Dustin (May 20, 2015). "Long: Bruton Smith's induction to NASCAR Hall of Fame helped by member of France family". NBC Sports. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 7, 2023.

- ^ "Business Hall of Fame to honor 4". The Charlotte Observer. September 16, 2006. p. 1D. Archived from the original on July 6, 2023. Retrieved July 5, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Poole, David (January 22, 2006). "Smith worthy of Hall". The Charlotte Observer. p. 3C. Archived from the original on July 6, 2023. Retrieved July 5, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hyatt, Brad (May 20, 2008). "Bruton Smith Boulevard Becomes a Reality". WBTV. Archived from the original on July 9, 2023. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ "Bruton Smith leads Talladega hall of fame". The Charlotte Observer. April 25, 2007. p. 8C. Archived from the original on July 6, 2023. Retrieved July 5, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Spencer, Reid (January 23, 2016). "NASCAR Hall of Fame inducts Class of 2016". NASCAR Wire Service. NASCAR Media Group, LLC. Archived from the original on January 24, 2016. Retrieved January 23, 2016.