Brushtalk

Brushtalk is a form of written communication using Literary Chinese to facilitate diplomatic and casual discussions between people of the countries in the Sinosphere, which include China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam.[1]

History

[edit]Brushtalk (simplified Chinese: 笔谈; traditional Chinese: 筆談; pinyin: bǐtán) was first used in China as a way to engage in "silent conversations".[2] Beginning from the Sui dynasty, the scholars from China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam could use their mastery of Classical Chinese (Chinese: 文言文; pinyin: wényánwén; Japanese: 漢文 kanbun; Korean: 한문; Hanja: 漢文; RR: hanmun; Vietnamese: Hán văn, chữ Hán: 漢文)[3] to communicate without any prior knowledge of spoken Chinese.

The earliest and initial accounts of Sino-Japanese brushtalks date back to during the Sui dynasty (581–618).[4] By an account written in 1094, minister Ono no Imoko (小野 妹子) was sent to China as an envoy. One of his goals there was to obtain Buddhist sutras to bring back to Japan. In one particular instance, Ono no Imoko had met three old monks. During their encounter, due to them not sharing a common language, held a "silent conversation" by writing Chinese characters on the ground using a stick.[4]

老僧書地曰:「念禪法師、於彼何號?」

The old monk wrote on the ground: "Regarding the Zen Master, what title does he have there?"

妹子答曰:「我日本國、元倭國也。在東海中、相去三年行矣。今有聖德太子、无念禪法師、崇尊佛道,流通妙義。自說諸經,兼製義疏。承其令有、取昔身所持複法華經一卷、餘无異事。」

Ono no Imoko answered: "I am from Japan, originally known as the Wa country. Situated in the middle of the Eastern Sea, it takes three years to travel here. Currently, we have Prince Shōtoku, but no Zen Master. He venerates the teachings of Buddhism, propagating profound teachings. He personally expounds upon various scriptures and creates commentaries on their meanings. Following his orders, I have come here to bring with me the single volume of the Lotus Sutra that he possessed in the past, and nothing else."

老僧等大歡、命沙彌取之。須臾取經、納一漆篋而來、

The old monk and others were overjoyed and instructed a novice monk to retrieve it. After a moment, the scripture was brought in, placed in a lacquered box.

The Vietnamese revolutionary Phan Bội Châu (潘佩珠) in 1905-1906 conducted several brushtalks with several other Chinese revolutionaries such as Sun Yat-sen (孫中山) and reformist Liang Qichao (梁啓超) in Japan during his Đông Du movement (東遊).[5][6] During his brushtalk with Li Qichao, it was noted that Phan Bội Châu was able to communicate with Liang Qichao using Chinese characters. They both sat at a table and exchanged sheets of paper back and forth. However, when Phan Bội Châu tried reading what he wrote in his Sino-Vietnamese pronunciation, the pronunciation was unintelligible to Cantonese-speaking Liang Qichao.[5] They discussed topics mainly involving the pan-Asian anti-colonial movement.[6] These brushtalks later led to the publishing of the book, History of the Loss of Vietnam (Vietnamese: Việt Nam vong quốc sử; chữ Hán: 越南亡國史) written in Literary Chinese.

During one brushtalk between Phan Bội Châu and Inukai Tsuyoshi (犬養 毅),[7]

君等求援之事、亦有國中尊長之旨乎?若此君主之國則有皇系一人爲宜、君等曾籌及此事

Inukai Tsuyoshi: "Regarding the matter of seeking assistance, has there also been approval from the esteemed figures within your country? If the country is a monarchy, it would be appropriate to have a member of the imperial lineage. Have you all considered this matter?"

有之。

Phan Bội Châu: "Yes"

宜翼此人出境不無則落於法人之手。

Inukai Tsuyoshi: "It is advisable to ensure that this person leaves the country so that he does not fall into the hands of the French authorities."

此、我等已籌及此事。

Phan Bội Châu: "We have already considered this matter."

以民黨援君則可、以兵力援君則今非其辰「時」。... 君等能隱忍以待机会之日乎?

Okuma Shigenobu, Inukai Tsuyoshi, and Liang Qichao: "Supporting you in the name of the party [of Japan] is possible, but using military force to aid you is currently not opportune. Can you gentlemen endure patiently and await the day for seizing the opportunity?"

苟能隱忍、予則何若爲秦庭之泣?

Phan Bội Châu: "If I could endure patiently, what reason do I have not to weep for help in the Qin court?"[a]

About a hundred of Phan Bội Châu's brushtalks in Japan can be found in Phan Bội Châu's book, Chronicles of Phan Sào Nam (Vietnamese: Phan Sào Nam niên biểu; chữ Hán: 潘巢南年表).[8]

There are several instances in the Chronicles of Phan Sào Nam that mentions brushtalks were used to communicate.

以漢文之媒介也

"used Literary Chinese as a [communication] medium"

孫出筆紙與予互談

"Sun [Yat-sen] took out a brush and paper so we can converse"

以筆談互問答甚詳

"using brushtalk, we engaged in serious and detailed question and answer exchanges."

Pseudo-Chinese

[edit]Kōno Tarō (河野 太郎) during his visit to Beijing in 2019 tweeted his schedule, but only using Chinese characters (no kana) as a way of connecting with Chinese followers. While the text is not like Chinese nor is it like Japanese, it was fairly understandable by Chinese speakers. It is a good example of Pseudo-Chinese (偽中国語) and how the two countries can somewhat communicate with each other with writing. The tweet resembled how brushtalks were used in the past.[10]

八月二十二日日程。同行記者朝食懇談会、故宮博物院Digital故宮見学、故宮景福宮参観、李克強総理表敬、中国外交有識者昼食懇談会、荷造、帰国。

Daily schedule of 22 August. Breakfast meeting with accompanying reporters, visit to the Forbidden City’s Digital Palace, visit to the Forbidden City’s Jingfu Palace, courtesy visit with Premier Li Keqiang, lunch meeting with experts on Chinese diplomacy, packing, and returning home.

Examples

[edit]One famous example of brushtalk is a conversation between a Vietnamese envoy (Phùng Khắc Khoan; 馮克寬) and a Korean envoy (Yi Su-gwang; 이수광; 李睟光) meeting in Beijing to wish prosperity for the Wanli Emperor (1597).[11][12] The envoys exchanged dialogue and poems between each other.[13] These poems followed traditional metrics which was made up of eight seven-syllable lines (七言律詩). It is noted by Yi Su-gwang that out of the 23 people in Phùng Khắc Khoan's delagation, only one person knew spoken Chinese meaning that the rest had to either use brushtalks or an interpreter to communicate.[14]

Two Poems in Presentation to the Envoys of Annam (贈安南國使臣二首) – Korean question

[edit]These poems were complied in the eighth volume (권지팔; 卷之八) of Yi Su-gwang's book, Jibongseonsaengjip (지봉선생집; 芝峯先生集).

贈安南國使臣其一 A Presentation to the Envoys of Annam, Part One

[edit]

|

|

|

Sino-Vietnamese transcription:

|

English translation:

|

贈安南國使臣其二 A Presentation to the Envoys of Annam, Part Two

[edit]

|

|

|

Sino-Vietnamese transcription:

|

English translation:

|

Reply to the Envoy of Joseon, Yi Su-gwang (答朝鮮國使李睟光) - Vietnamese response

[edit]These poems were complied in Phùng Khắc Khoan's book, Mai Lĩnh sứ hoa thi tập (梅嶺使華詩集).

答朝鮮國使李睟光其一 Reply to the Envoy of Joseon, Yi Su-gwang, Part One

[edit]

|

Sino-Vietnamese transcription:

|

|

|

English translation:

|

答朝鮮國使李睟光其二 Reply to the Envoy of Joseon, Yi Su-gwang, Part Two

[edit]

|

Sino-Vietnamese transcription:

|

|

|

English translation:

|

Brushtalk with Lê Quý Đôn and I Sangbong

[edit]Another encounter with Korean envoy (I Sangbong; Korean: 이상봉; Hanja: 李商鳳) and Vietnamese envoy (Lê Quý Đôn; chữ Hán: 黎貴惇) on 30 December 1760, led to a brushtalk about the dress customs of Đại Việt (大越), it was recorded in the third volume of the book, Bugwollok (북원록; 北轅錄),[16]

(黎貴惇)副使曰:「本國有國自前明時、今王殿下黎氏、土風民俗、誠如來諭。敢問貴國王尊姓?」

The vice envoy (Lê Quý Đôn) said: "Our country has had its governance since the Ming Dynasty. Now, under the reign of His Royal Highness, the Lê family's local customs and traditions are indeed as mentioned. May I respectfully inquire about the surname of your esteemed royal highness?"

李商鳳曰:「本國王姓李氏。貴國於儒、佛何所尊尚?」

I Sangbong said: "In our country, the king's surname is I (李). In your esteemed country, what is revered and esteemed between Confucianism and Buddhism?"

黎貴惇曰:「本國並尊三教、第儒教萬古同推、綱常禮樂、有不容捨、此以為治。想大國崇尚亦共此一心也。」

Lê Quý Đôn said: "In our country, we equally respect the three teachings, but Confucianism, with its eternal principles, rites, and music, is universally upheld. These are considered essential for governance. I believe that even in great countries, the pursuit of such values is shared with the same sincerity."

李商鳳曰:「果然貴國禮樂文物、不讓中華一頭、俺亦慣聞。今覩盛儀衣冠之制、彷彿我東、而被髮漆齒亦有所拠、幸乞明教。」

I Sangbong said: "Indeed, the cultural artifacts of your esteemed country, especially in rituals, music, and literature, are no less impressive than those of China. I have heard about it before. Today, seeing the splendid ceremonial attire and the regulations for attire and headgear, it seems reminiscent of our Eastern customs. Even the hairstyles and the lacquered teeth has its own basis. Fortunately, I can inquire and learn more. Please enlighten me."

I Sangbong was fascinated with the Vietnamese custom of teeth blackening after seeing the Vietnamese envoys with blackened teeth.[16]

A passage in the book, Jowanbyeokjeon (Korean: 조완벽전; Hanja: 趙完璧傳), also mentions these customs,[17]

其國男女皆被髮赤脚。無鞋履。雖官貴者亦然。長者則漆齒。

In that country, both men and women all tie up their hair and go barefoot, without shoes or sandals. Even officials and nobility are the same. As for the respected individuals, they blacken their teeth.

The author Jo Wanbyeok (Korean: 조완벽; Hanja: 趙完璧) was sold to the Japanese by the Korean military, but since he was excellent in reading Chinese characters, the Japanese traders brought him along. From there, he was able to visit Vietnam and was treated as an guest by Vietnamese officials. His biography, Jowanbyeokjeon records his experiences and brushtalks with the Vietnamese.[18]

Brushtalks between Japanese and Vietnamese

[edit]Maruyama Shizuo (丸山 静雄), a journalist working in Vietnam noted that he held brushtalks with locals in his book, The Story of Indochina (印度支那物語, Indoshina monogatari),[19]

わたしは終戦前、ベトナムがまだフランスの植民地であったころ、朝日新聞の特派員としてベトナムに滞在した。わたしはシクロ(三輪自転車)を乗りついだり、路地から路地にわざと道を変えて、ベトナムの民族独立運動家たちと会った。大方、通訳の手をかり、通訳いない場合は、漢文で筆談したが、結構、それで意が通じた。いまでも中年以上のものであれば、漢字を知っており、わたしどもとも漢字で大体の話はできる。漢字といっても、日本の漢字と、二の地域のそれとはかなり違うが、漢字の基本に変りはないわけで、中国-ベトナム-朝鮮-日本とつながる漢字文化圏の中に、わたしどもは生きていることを痛感する。

"Before the end of the war (World War II), when Vietnam was still a French colony, I went to Vietnam as a correspondent for Asahi Shimbun. I rode a cyclo (three-wheeled bicycle taxi), deliberately traveling through alleys and lanes to meet with Vietnamese nationalists. Most of the time, I relied on interpreters, and when there was none, I communicated through brushtalks in Classical Chinese, which worked surprisingly well. Even now, anyone who is middle-aged or older knows Chinese characters, we can communicate roughly using Chinese characters. Speaking of Chinese characters, although they are quite different from those in Japan, the basics of Chinese characters remain unchanged. I am keenly aware that we are living in Chinese character cultural sphere that is connected to China, Vietnam, Korea, and Japan."

In the 18th century Japanese book, An Account of Drifting in Annam (安南国漂流記, Annan-koku Hyōryū-ki), mentions a drifter's account in Annam.

通候間、庄兵衛即テ日本水戸国と砂に書付見セ候得共、本之字不審之様子相見候故、本之字直ニ本と替候へハ合点之躰ニ御座候、其後飢に及候間食事あたへ呉候得と仕方ニて知らせ申候、先よりも色々言語いたし候得共少も通シ不申候、庄兵衛ハ船へ帰り其次第を知らせ、佐平太、十三郎も陸へ上りて米と云字を書て見セ候得者早速米四升計持来り候、悉飢候故四人とも打寄二握宛かみ候、又一握と手を掛ケ候所ニ里人共手を押へ、米ハ腹へあたり候間、飯を炊あたへべきとの仕方をいたし候間、我々も又船中の両人へ少シ給度と仕方でしらせ少々宛かまセ残をは炊セ候。

"During that time, Shōbē (庄兵衛) immediately wrote 'Japan, Mito Province' (日本水戸国) in the sand and showed it to the villagers. However, they did not recognize some of the characters, so when he rewrote the character for 'hon' (本) more clearly, they seemed to understand. Afterwards, since Shōbē and the others were hungry, he gestured to the villagers asking for food, but nothing was understood despite trying to communicate earlier by gestures. Shōbē returned to the boat and reported the situation. Saheita (佐平太) and Jūzaburō (十三郎) also went ashore, wrote the character for 'rice' (米) and showed it to them. Immediately, they brought about four shō (四升) of rice. Being extremely hungry, the four of them gathered and each took two handfuls to eat. When they reached out for another handful, the villagers held their hands and gestured that since raw rice is bad for the stomach, they should cook it first and give it to them. We then gestured that we would also like a little for the two men left on the boat, and the remaining rice was cooked for us."

A letter sent from Tokugawa Ieyasu (源家康) to Nguyễn Hoàng (chữ Hán: 阮潢) in 1607 shows the diplomatic relations between Japan and Vietnam during that period. The letter reads,

安南國大都統瑞國公、敬回翰。

日本國本主一位源家康王殿下曰。交鄰之道、以信為重。兹日本國與安南國、卦域雖殊、地軸星象、正一天樞。伏荷國王量同滄海、惠及陋邦、每歳遣通商舶資以兵噐之用、職蒙恩厚矣。奈其報答未孚於心、何復覩。玉章芳情道達、實有含弘之量也。兹職欲堅信義、爰逹雲箋、虔將土產小物遙贈為贄、所望國王兼愛心、推曲岳笑納、以通两國之情、以結億年之好、至矣。

弘定㭍年五月拾叁日

書 (seal)

To the Grand Commander of Annam, the Duke of Thuỵ State, I respectfully return this letter.

The sovereign of Japan, the senior first-rank lord Tokugawa Ieyasu, said: In the way of maintaining neighbourly relations, trust is of utmost importance. Although the territories of Japan and Annam differ, our lands are aligned under the same celestial principles, sharing the same axis and stars, as if connected to the pivot of the heavens. I am deeply grateful to the king for his generosity, as vast as the sea, which has benefited my humble country. Each year, merchant ships are dispatched, bringing supplies, including those for military use, and I have received such generous treatment. However, my sense of gratitude remains unfulfilled, and I am unable to fully express my appreciation for the noble sentiments conveyed in the precious letter, which reflect the king’s benevolence. I wish to affirm my commitment to trust and loyalty, and thus send this letter with the utmost respect. I humbly present a small gift of local products from afar, hoping that the king will graciously accept it as a token of goodwill. It is my hope that this will further the friendship between our two nations and establish a bond that will last for countless years.

Written on the thirteenth day of the fifth month in the seventh year of Hoằng Định.

In media

[edit]- A scene in The Partner, a 2013 Japanese-Vietnamese historical film, showed a brushtalk between Phan Bội Châu and Inukai Tsuyoshi (犬養 毅).

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Weeping for help in the Qin court" was referring to a moment in Zuo Zhuan, where Shen Baoxu (Chinese: 申包胥) cried at the Qin court for seven days without eating. Duke Ai of Qin (Chinese: 秦哀公) moved by his actions sent troops to restore the Chu State(立依於庭牆而哭,日夜不絕聲,勺飲不入口,七日,秦哀公為之賦無衣,九頓首而坐,秦師乃出。)

- ^ Việt Thường 越裳 refers to an ancient nation mentioned by Book of the Later Han, the location of Việt Thường is said to be in Northern Vietnam according to the Vietnamese history book, Đại Việt sử lược 大越史略.

- ^ Cửu Chân 九真 refers to an ancient Vietnamese province while Vietnam was under Chinese rule. It is now present-day Thanh Hóa Province.

- ^ Yanzhou 炎州 refers to a distant place in the South.

- ^ Uian 의안; 義安 first referred to an island historically under the control of Korea, but later fell to the control of the predecessor of the Ryukyu Kingdom during the Goguryeo–Sui War. In this context, it refers to Korea.

References

[edit]- ^ Li, David Chor-Shing; Aoyama, Reijiro; Wong, Tak-sum (6 February 2020). "Silent conversation through Brushtalk (筆談): The use of Sinitic as a scripta franca in early modern East Asia". Global Chinese. 6 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1515/glochi-2019-0027 – via De Gruyter.

Literary Sinitic (written Chinese, hereafter Sinitic) functioned as a 'scripta franca' in sinographic East Asia, which broadly comprises China, Japan, South Korea and North Korea, and Vietnam today.

- ^ Li, David Chor-Shing (17 February 2021). "Writing-Mediated Interaction Face-to-Face: Sinitic Brushtalk (漢文筆談) as an Age-Old Lingua-Cultural Practice in Premodern East Asian Cross-Border Communication". China and Asia. 2 (2): 193–233. doi:10.1163/2589465X-02020002. hdl:10397/89467 – via Brill.

Based on selected documented examples of writing-mediated cross-border communication spanning over a thousand years from the Sui dynasty to the late Ming dynasty, this paper demonstrates that Hanzi 漢字, a morphographic, non-phonographic script, was commonly used by literati of classical Chinese or Literary Sinitic to engage in "silent conversation" as a substitute for speech.

- ^ Li, David Chor-Shing (17 February 2021). "Writing-Mediated Interaction Face-to-Face: Sinitic Brushtalk (漢文筆談) as an Age-Old Lingua-Cultural Practice in Premodern East Asian Cross-Border Communication". China and Asia. 2 (2): 195–196. doi:10.1163/2589465X-02020002. hdl:10397/89467 – via Brill.

The same is not true of premodern and early modern East Asia, however, where, for well over a thousand years from the Sui dynasty (581–618 CE) until the 1900s, literati from today's China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam with no shared spoken language could mobilize their knowledge of classical Chinese (wenyan 文言) or Literary Sinitic (Hanwen 漢文, Jap: kanbun, Kor: hanmun 한문, Viet.: hán văn) to improvise and make meaning through writing, interactively and face-to-face.

- ^ a b Li, David Chor-Shing (17 February 2021). "Writing-Mediated Interaction Face-to-Face: Sinitic Brushtalk (漢文筆談) as an Age-Old Lingua-Cultural Practice in Premodern East Asian Cross-Border Communication". China and Asia. 2 (2): 202. doi:10.1163/2589465X-02020002. hdl:10397/89467 – via Brill.

Among the earliest writing-mediated "silent conversation" records involving Japanese visitors in China was an anecdote documented during the Sui dynasty. According to an account in Fusō ryakuki 扶桑略记 written in year 1094 CE, minister Ono no Imoko小野妹子 (ca. 565−625) was dispatched by the Japanese Prince Shōtoku 聖德太子 (572−621) as an envoy to Sui China. One of the purposes of his voyage across the East Sea was to collect Buddhist sutras.

- ^ a b Li, David Chor-Shing; Aoyama, Reijiro; Wong, Tak-sum (6 February 2020). "Silent conversation through Brushtalk (筆談): The use of Sinitic as a scripta franca in early modern East Asia". Global Chinese. 6 (1): 4. doi:10.1515/glochi-2019-0027 – via De Gruyter.

In two monographs, Vietnamese Anticolonialism 1885–1925 (Marr 1971) and Colonialism and Language Policy in Viet Nam (DeFrancis 1977), the historical background of several brush conversations between a Vietnamese anticolonial leader Phan Bội Châu 潘佩珠 (1867−1940), his Chinese contacts – reformist Liang Qichao 梁啓超 (1873−1929) and revolutionary leader Sun Yat-sen 孫逸仙 (better known in Chinese as 孫中山, 1866−1925), and Japanese leaders in 1905–1906 is covered in considerable detail (see also Phan 1999a[n.d.]): Here [in Japan] Phan Boi Chau sought out Liang Qichao, a refugee from the wrath of the Emperor Dowager, and has several extended discussions with him. Their common language was Chinese, but in written form, for while Phan Boi Chau was able to read and write Chinese his Sino-Vietnamese pronunciation was unintelligible to his interlocutor. They sat together at a table and passed back and forth to each other sheets covered with Chinese characters written with a brush. (DeFrancis 1977: 161; cf. Phan 1999b[n.d.]: 255)

- ^ a b Li, David Chor-Shing; Aoyama, Reijiro; Wong, Tak-sum (2024). Brush Conversation in the Sinographic Cosmopolis Interactional Cross-border Communication using Literary Sinitic in Early Modern East Asia (1st ed.). Routledge (published 29 January 2024). pp. 295–298. ISBN 9780367499402.

One of the most widely respected figures in Vietnam's modern history, Phan Bội Châu is known for initiating the struggle against the French colonial rule and organizing Đông-Du Movement 東遊運動 or Go East Movement... When he visited Liang Qichao at his home in Yokohama, the first part of their conversation was assisted by Tăng Bạt Hổ 曾拔虎 (1856–1906), Phan's Vietnamese travel companion who spoke some Cantonese and translated orally for Phan and Liang. This got them only so far, however, and every time the conversation turned to a more intricate or momentous subject, the two scholars would resort to brush-talk to clarify their intentions and record their ideas in written form.

- ^ Nguyễn, Hoàng Thân; Nguyễn, Tuấn Cường (17 Feb 2021). "Sinitic Brushtalk in Vietnam's Anti-Colonial Struggle against France: Phan Bội Châu's Silent Conversations with Influential Chinese and Japanese Leaders in the 1900s". China and Asia. 2 (2): 281. doi:10.1163/2589465X-02020004 – via Brill.

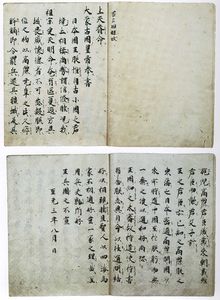

To illustrate the format and contents of a brushtalk, we will present a conversation at Count Okuma's home involving five interlocutors: Phan, Okuma, Inukai, Liang, and Kashiwabara. This brushtalk is quite long, and so only a part of this political conversation is excerpted for illustration (see Excerpt in Fig. 1).

- ^ Nguyễn, Hoàng Thân; Nguyễn, Tuấn Cường (17 Feb 2021). "Sinitic Brushtalk in Vietnam's Anti-Colonial Struggle against France: Phan Bội Châu's Silent Conversations with Influential Chinese and Japanese Leaders in the 1900s". China and Asia. 2 (2): 274–275. doi:10.1163/2589465X-02020004 – via Brill.

The contents of the brushtalks of Phan and the Go East group with Japanese and Chinese leaders were noted in Phan's Sinitic autobiography, Chronicles of Phan Sào Nam (Phan Sào Nam niên biểu 潘巢南年表), recording his life from his birth in 1867 to the time he was arrested and escorted to Vietnam in 1925.

- ^ Li, David Chor-Shing; Aoyama, Reijiro; Wong, Tak-sum (2024). Brush Conversation in the Sinographic Cosmopolis Interactional Cross-border Communication using Literary Sinitic in Early Modern East Asia (1st ed.). Routledge (published 29 January 2024). p. 158. ISBN 9780367499426.

During this trip, the Chosŏn envoy, Yi Su-Kwang 李睟光 (1563–1629) met two emissaries from Ryukyu, Sai Ken 蔡堅 (1587–1647) and Ba Seiki 馬成驥. Not only did they improvise and exchange poetic verses, Yi also took this opportunity to ask about the geographical location, political and socioeconomic conditions of the Ryukyu Kingdom in the form of questions and answers through brush-talking.

- ^ Aoyama, Reijiro (17 February 2021). "Writing-Mediated Interaction Face-to-Face: Sinitic Brushtalk in the Japanese Missions' Transnational Encounters with Foreigners During the Mid-Nineteenth Century". China and Asia. 2 (2): 238–239. doi:10.1163/2589465X-02020003 – via Brill.

During his official visit to Beijing in 2019, Kōno Tarō 河野太郎, who does not speak Chinese, posted his daily schedule on Twitter using only Chinese characters (i.e., without using any input from the kana syllabaries). The aim of the gesture could be interpreted as the envoy's way of connecting with the Chinese followers, which in some respects harks back to the diplomatic brushtalk tradition of the past... Furthermore, the text is a good illustration of "fake Chinese" or "pseudo-Chinese" (偽中国語), a form of contemporary internet slang used mainly by Japanese social media users and occasionally adopted for playful Sino-Japanese written communication.

- ^ 陈, 俐; 李, 姝雯 (2017). "朝鮮、安南使臣詩歌贈酬考述 — 兼論詩歌贈酬的學術意義" [The Study on the Poetry presented between Chosŏn and Vietnam - On the academic significance of the present of poetry]. 중국연구. 71: 3–23. doi:10.18077/chss.2017.71..001.

- ^ Aoyama, Reijiro (17 February 2021). "Writing-Mediated Interaction Face-to-Face: Sinitic Brushtalk in the Japanese Missions' Transnational Encounters with Foreigners During the Mid-Nineteenth Century". China and Asia. 2 (2): 236. doi:10.1163/2589465X-02020003 – via Brill.

When Yi Su-gwang (李睟光, 1563−1628), the Korean envoy to Ming China (1368−1644), met Phùng Khắc Khoan (馮克寬, 1528−1613), his Vietnamese counterpart, in Beijing in 1597, the two men were able to overcome the spoken language barrier and discuss political and admin- istrative affairs using Sinitic brushtalk.

- ^ Li, David Chor-Shing; Aoyama, Reijiro; Wong, Tak-sum (6 February 2020). "Silent conversation through Brushtalk (筆談): The use of Sinitic as a scripta franca in early modern East Asia". Global Chinese. 6 (1): 14–15. doi:10.1515/glochi-2019-0027 – via De Gruyter.

The following hepta-syllabic octave, entitled Đáp Triều Tiên quốc sứ Lý Tuý Quang 答朝鮮國使李晬光 ('Response to Chosŏn Ambassador Li Swu-Kwang'), was produced by a Vietnamese diplomat Phùng Khắc Khoan 馮克寬 (1528−1613) in response to two poems – also hepta-syllabic octaves – composed by Li as part of their semi-official, semi-social encounters during the late Ming dynasty in Peking.

- ^ Nguyễn, Dị Cổ (11 December 2022). "Người Quảng xưa "nói chuyện" với người nước ngoài". Báo Quảng Nam (in Vietnamese).

Lý Tối Quang - sứ giả Triều Tiên tại Trung Quốc đã quan sát về sứ đoàn Việt Nam lúc bấy giờ và chép rằng: "đoàn sứ thần Phùng Khắc Khoan có 23 người, đều búi tóc, trong đó chỉ có một người biết tiếng Hán để thông dịch, còn thì dùng chữ viết để cùng hiểu nhau".

- ^ Clements, Rebekah (June 2019). "Brush talk as the 'lingua franca' of diplomacy in Japanese-Korean encounters, c. 1600–1868". The Historical Journal. 62 (2): 298. doi:10.1017/S0018246X18000249 – via Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b 沈, 玉慧 (December 2012). "乾隆二十五~二十六年朝鮮使節與安南、南掌、琉球三國人員於北京之交流 (Joseon Envoys' Intercourse with Annam, Lan Xang, and Ryukyu in Beijing during 1760-1761 )". 臺大歷史學報. 12 (50): 120. doi:10.6253/ntuhistory.2012.50.03 – via Airiti Library.

交談結束後,李商鳳即前往安南使節館舍,將正使洪啟禧所託之別箑、雪花紙、大好紙及書信贈予安南使節,安南使節則以檳榔款待。李商鳳即以筆談展開對話:

- ^ 李, 睟光. 趙完璧傳 (조완벽전).

- ^ 南 Nam, 美惠 Mi-hye (February 2016). "17세기(世紀) 피로인(被擄人) 조완벽(趙完璧)의 안남(安南) 체험" [A Study on the Annam experience of Cho Wan-byuk (趙完璧) as a Captive in the 17th century]. 한국학논총 – via KISS.

조완벽은 안남에서 많은 사람들을 만나 필담으로 대화를 나누면서 한자문화권 내부의 동질감과 이질감을 느꼈던 것으로 보인다.

- ^ 丸山, 静雄 (26 October 1981). 印度支那物語 [The Story of Indochina] (in Japanese) (1st ed.). Japan: 講談社.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link)