Brook Waimārama Sanctuary

| Brook Waimārama Sanctuary | |

|---|---|

Bridge across the Brook Stream | |

| |

| Location | New Zealand |

| Nearest city | Nelson |

| Coordinates | 41°18′55″S 173°17′30″E / 41.315185°S 173.291668°E |

| Area | 700 hectares (1,700 acres) |

| Elevation | 100 to 850 metres (330 to 2,790 ft) |

| Established | 2004 |

| Administered by | Brook Waimārama Sanctuary Trust |

| Open | Fri, Sat, Sun, 10am–4pm; Summer hours: 7 days, 9am–6pm |

| Habitats | Southern beech forest |

| Water | Brook Stream |

| Parking | At Visitor Centre |

| Public transit access | Route 4 to motor camp gate, 10 minute walk to Visitor Centre |

| Website | www.brooksanctuary.org.nz |

The Brook Waimārama Sanctuary is a nearly 700 hectare mainland "ecological island" sanctuary located 6 km south of Nelson, New Zealand. The sanctuary is the largest fenced sanctuary in New Zealand's South Island and the second largest in the country; it is the only sanctuary to feature mature New Zealand beech forest.

The Brook Waimārama Sanctuary Trust was established in 2004 with the intent of restoring the flora and fauna of the Brook Valley, a former water supply for Nelson with intact beech forest. A predator-proof fence was completed in 2016 at a cost of NZD $4.2 million, and introduced mammalian pests were eradicated from within the sanctuary in 2017. The sanctuary reopened to the public in 2018, and an entrance fee regime was introduced in 2020. Reintroductions of species such as the Okarito kiwi are planned.

Origins

[edit]

The Brook Valley immediately south of Nelson is a water-supply reserve owned for over 100 years by the Nelson City Council. The Nelson Waterworks Reserve was created in 1865, encompassing the watershed of the Brook Stream. A dam was built and an oval reservoir were constructed that held a two-week water supply for the city; they opened on 16 April 1868.[1] A second dam was built in 1905, and a third in 1909, to create enough water pressure to supply houses in the hills around Nelson. The dams were plagued with leaks, and the city's water needs continued to grow. A dam and pipeline were built on the Roding River in 1941, and the Maitai River was dammed in 1987.[2] Together these rendered the Brook waterworks obsolete, and it was decommissioned in 2000.[1]

The valley also contained the Dun Mountain railway line, New Zealand's first railway, which was a horse-drawn tramway built in the 1860s to service a chromite mine. In the 1890s two coal mines operated nearby.[3]

Planning for turning the Brook Valley into a predator-free wildlife sanctuary began with the formation of a steering committee in mid-2001, and in 2004 the Brook Waimārama Sanctuary Trust was formed as a community group.[4][5] The valley was only 5 km from Nelson, backed onto 1660 km2 Mount Richmond Forest Park, and included the 690 ha Waterworks Reserve.[4] Although its lower reaches had been initially cleared for grazing livestock and were regenerating, the beech forest in the upper reaches had been preserved as a water-supply reserve and was intact.[6]

In 2007–2008 the Nelson City Council approved $1.036 million and the Tasman District Council $300,000 of funding to begin the project.[5]

Fencing

[edit]

The plan for the Brook Waimārama included a predator-proof fence, to prevent reinvasion by introduced predatory mammals after eradication had been completed. A resource consent for the fence was secured in 2009, and the fence route surveyed in 2010.[5] The area to be protected was three times the size of Zealandia, with a fence twice as long – the largest wildlife sanctuary in the South Island, and the second-largest in New Zealand.[5]

The predator-proof fence was finished in September 2016 after 12 years of planning and 18 months of construction.[7] The fence is 14.4 km long, and cost $4.2 million. In addition to the Nelson City Council and Tasman District Council funding, $574,000 was raised in donations (including a one-off anonymous donation of $250,000), and the remaining $1.75 million came from a Lottery grant.[5][7] An electric wire runs the length of the fence hood to detect when branches fall on it that might allow a predator to cross.[5]

Pest control

[edit]

A trapping programme began in a small area of secondary forest in 2006 aimed at controlling possum, rat, mice, stoat and weasel populations. A team of volunteers cut 22 km of tracks spaced 100 m apart around the valley, allowing traps to be set up on a 100 m grid (50 m around the perimeter). The traps were baited weekly. Shooters also killed about 100 goats that had been ring-barking trees in the valley.[1]

Three aerial drops of 26.5 tonnes of brodifacoum-laced bait to eliminate all rodents within the fence were planned for July to October 2017. This action was challenged in June by a group calling themselves the Brook Valley Community Group (BVCG), led by Nelson lawyer Sue Grey, who protested the aerial poison drop near a waterway.[8] Although portraying themselves as a community group, many of the organisers were anti-1080 activists from outside Nelson.[9] The drop was halted while the case went to the High Court on 7 August, and then, two days before the first drop, to the Court of Appeal; in both cases the court ruled against the BVCG.[10] Nelson MP Nick Smith was accosted on 3 September 2017 (the day of the first drop) by activist Rose Renton and her then husband, who allegedly rubbed rat poison on his clothes and intimidated him in an act of protest; both were found guilty of offensive behaviour.[10][11] That same day, a hole was drilled in a fuel tank for helicopters performing the drop, several protesters attempted to block access, and three were arrested.[12][9] The three poison drops subsequently went ahead smoothly, and no bait was dropped outside the sanctuary boundaries, nor was any trace of brodifacoum detected in the stream water.[13][14]

The BVCG attempted to take their appeal to the Supreme Court, but were denied, and they were ordered to pay over $70,000 in legal costs to the Nelson City Council, the Minister for the Environment, and the Brook Waimārama Sanctuary Trust.[15] The group considered disbanding as an incorporated society to avoid having to pay the costs and "starting again somewhere else".[9][16] After attempting to recover some of the $100,000 it had spent responding to the BVCG's legal action, the Nelson City Council applied for the group to be liquidated.[17]

After six months of monitoring, the sanctuary was declared "pest free" in 2018, with at least 14 pest species removed from within the fence, including rats, stoats, and deer.[18] A four-monthly testing regime checks for presence of rodents; as of May 2019 there had been two breaches of the fence, both individual rats which were dealt with shortly afterwards.[19] In the year following the elimination of rodents there was 400 per cent increase in the numbers of tūī and bellbirds, and a 200 per cent increase in fantails and tomtits.[19] There were also notable increases in the number of ground invertebrates and tree seedlings.[20]

Reopening

[edit]The sanctuary reopened to the public on Sunday 15 July 2018.[18] It featured an outdoor classroom space with electricity for visiting school groups, a wheelchair-accessible loop track, and bridges over the former dams.[19] The visitor centre, designed by John Palmer of Palmer & Palmer Architects, had been operating since 2007.[4] A wheelchair-accessible bridge was scheduled to be opened in February 2020, but the Sanctuary was forced to temporarily close due to the high summer fire risk.[21]

Gallery

[edit]-

View from air

-

View up the valley

-

Beech grove outdoor classroom

-

Weir

-

Another view of the weir

-

Shining spleenwort (Asplenium oblongifolium)

-

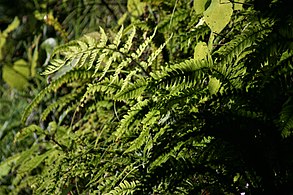

Ferns on the forest floor

-

QR code for tracking tunnel

-

Visitor centre

-

Weka and chick

Governance

[edit]From 2004 to 2019 the Brook Waimārama Sanctuary Trust was chaired by Dave Butler, who had been involved with the project from the beginning; he had previously managed the ecological island setup at Lake Rotoiti in Nelson Lakes National Park.[4] The Acting Chair Peter Jamieson was replaced in 2019 by Chris Hawkes.[19]

The first general manager of the Trust was Hudson Dodd, who started in January 2012 and played a major role in the fundraising for the fence and pest removal.[22] Dodd stepped down in November 2018 and was replaced as CEO in January 2019 by Ru Collin.[20][19]

As part of Nelson City Council's Long Term Plan, the sanctuary received $250,000 for the 2018–2019 financial year, with a further $150,000 each year for the nine remaining years of the Plan.[18] One third of the Sanctuary's annual budget comes from Nelson City Council, the Department of Conservation, and Jasmine Social Investments; the remainder is from sponsorship and donations.[23] After missing out on $50,000 of additional Council funding its annual budget, previously $850,000, dropped to $660,000.[23] In January 2020 the Sanctuary announced that it would be replacing its voluntary entry fee of $5 ($15 for families) with a compulsory fee of $15 for adults, $8 for those under 15 years, and $40 for families. These fees would be halved for Nelson or Tasman residents, students, and unwaged.[24]

Flora

[edit]

Brook Waimārama Sanctuary contains over 250 species of vascular plants, including pukatea (Laurelia novae-zelandiae) and tawa (Beilschmiedia tawa) which are close to their southern limits here.[1] About two thirds of the valley consists of intact Southern beech forest, including all five beech species, along with mataī, rimu, and tōtara.[6] The remainder in the north-west is a mixture of kānuka, mānuka, and regenerating broadleaf forest.[4]

Threatened species

[edit]- Red mistletoe (Peraxilla tetrapetala)

Uncommon species

[edit]- Forest parsley fern (Botrychium biforme)

- Gully tree fern (Alsophila cunninghami)

- Lace filmy fern (Hymenophyllum flexuosum)

- Notched glade fern (Hypolepsis distans)

- Green mistletoe (Ileostylus micranthus)

- Velvet fern (Lastreopsis velutina)

- Bamboo grass (Microlaena polynoda)

Fauna

[edit]Tūī, bellbirds, fantails, kererū, grey warblers, brown creepers, silvereyes, and tomtits are common in the sanctuary, and South Island robins and riflemen, which had previously lived in the upper reaches, are increasingly venturing into the valley bottom.[19] In April 2021, the sanctuary reached a milestone with first species reintroduction 40 tīeke/South Island saddleback (Philesturnus carunculatus) were released into the sanctuary. Orange-fronted parakeet / kākāriki karaka (Cyanoramphus malherbi) were introduced successfully (seven translocations totalling 125 birds from several sources by March 2023[25]). Some nationally uncommon species are also present, such as New Zealand falcons/kārearea.[4] The Sanctuary's long-term plan is to re-introduce several further threatened bird species:[19]

- Rowi or Okarito kiwi (Apteryx rowi), from the population on Motuara Island (although this has been delayed several years following a rat incursion in September 2018)[26]

- Kākā (Nestor meridionalis)[27]

- Yellowhead / mōhua (Mohoua ochrocephala)[26]

In 2022 the threatened giant snail Powelliphanta hochstetteri consobrina was re-introduced into the sanctuary.[28]

In the stream are freshwater crayfish (kōura) and kōaro (Galaxias brevipinnis).[4] Nelson green geckos (Naultinus stellatus) are present, and tuatara are included in the Sanctuary reintroduction plan.[4] In November 2024 56 Tuatara were bought to a 5.7 acre mouse-free enclosure marking it as the first time tuatara were reintroduced to the northern South Island.[29] https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/533045/dozens-of-tuatara-to-be-released-at-brook-waimarama-sanctuary-in-nelson Of the invertebrates, huhu beetles and Tree wētā are most noticeable, and wētā "hotels" have been installed beside the walking track.[4]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Bell, Jacquetta (2008). Returning nature to the Nelson Region : the Brook Waimarama Sanctuary. Nelson, N.Z.: Nikau Press. ISBN 978-0-9582898-0-1. OCLC 237072809.

- ^ Bathgate, Janet (2008). "Roding Valley waterworks". www.theprow.org.nz. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- ^ Murphy, Michael. "The Longer, Historic Detail". Brook Waimārama Sanctuary | Returning Nature to the Nelson Region. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Schadewinkel, Robert (2019). Volunteer Reference Guide. Nelson, New Zealand: Brook Waimārama Sanctuary.

- ^ a b c d e f Arnold, Naomi (17 June 2013). "The two sides of the fence". Nelson Mail. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ^ a b Shaw, Derek (9 August 2017). "Brook Waimarama Sanctuary's key conservation role". Stuff. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ a b Meij, Sara (27 September 2016). "Brook Waimarama Sanctuary pest-proof fence completed". Nelson Mail. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ Meij, Sara (5 August 2017). "Nelson Brook Sanctuary wins High Court ruling on poison drop". Nelson Mail. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ a b c Hansford, Dave (9 September 2017). "Zealots ransack vision for the Brook Sanctuary". Stuff. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ^ a b Sivignon, Cherie (3 September 2017). "Pair rub poison in face of Nelson MP Nick Smith, threaten family". Nelson Mail. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ Gee, Samatha (12 July 2018). "Rose Renton guilty of offensive behaviour after poison incident". Stuff. Archived from the original on 14 July 2018. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- ^ Sivignon, Cherie (2 September 2017). "Three arrests as Brook Sanctuary poison drop in Nelson turns nasty". Stuff. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ Meij, Sara (11 September 2017). "Tracking map shows Brook sanctuary poison drop stayed within fence". Stuff. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ Meij, Sara (19 September 2017). "Water testing shows "no detectable residue" after Brook Sanctuary poison drop". Nelson Mail. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ^ Bohny, Skara (21 May 2019). "Supreme Court dismisses Brook Valley group's appeal over poison drop". Stuff. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ Bohny, Skara (28 May 2019). "Brook Valley group not ruling out disbanding to avoid court costs". Stuff. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ Bohny, Skara (20 February 2020). "Broke Brook Valley group asks council not to liquidate for court costs". Nelson Mail. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ a b c O'Connell, Tim (15 July 2018). "Brook Sanctuary reopens to the public". Nelson Mail. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bohny, Skara (24 May 2019). "Nelson's Brook Sanctuary hopes to introduce South Island kiwi this year". Nelson Mail. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ a b O'Connell, Tim (28 November 2018). "Brook Sanctuary boss stepping down but leaves with an enduring legacy". Nelson Mail. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ Bohny, Skara (13 February 2020). "Fire restrictions hit Brook Sanctuary". Nelson Mail. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ Basham, Laura (28 January 2012). "Now he's keeping predators away". Nelson Mail.

- ^ a b Bohny, Skara (21 January 2020). "Brook Sanctuary wins sustainability award, introduces compulsory entry fee". Nelson Mail. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ Russell, Kate (16 January 2020). "Brook Sanctuary confirms entry charges". Nelson Weekly. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ ENews from Brook Sanctuary, March 2023, 2

- ^ a b Bohny, Skara (3 December 2019). "Rat breach delays kiwi introduction to Brook sanctuary". Stuff. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ Collen, Rose (11 October 2012). South Island Kaka Captive Management Plan 2010-2020 (PDF) (Report). Wellington, New Zealand: Department of Conservation, Government of New Zealand. p. 6. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- ^ "Threatened giant snails expected to thrive in sanctuary's soils". RNZ. 2 July 2022. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/533045/dozens-of-tuatara-to-be-released-at-brook-waimarama-sanctuary-in-nelson

Further reading

[edit]- Bell, Jacquetta (2008). Returning Nature to the Nelson Region: The Brook Waimarama Sanctuary. Nikau Press. 32 p. ISBN 0-9582898-0-8, ISBN 978-0-9582898-0-1

- Malcolm, Bill; Malcom, Nancy; Shevock, Jim (2015). Waimarama Sanctuary Mosses. Nelson, New Zealand: Micro-Optics Press. ISBN 978-0-9582224-8-8.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- RNZ Our Changing World episode on the Brook Waimārama Sanctuary, 24 March 2016