British logistics in the Western Allied invasion of Germany

British logistics supported the operations of Field Marshal Sir Bernard Montgomery's Anglo-Canadian 21st Army Group in the Western Allied invasion of Germany from 8 January 1945 until the end of the Second World War in Europe on 8 May 1945. To conserve scarce manpower, the British and Canadian forces employed mechanisation and materiel for maximum effect in combat operations. This involved prodigious use of ammunition, fuel, and equipment, which in turn demanded a first-class military logistics system. By this time, the British Army was highly experienced, professional, and proficient.

Originally scheduled to start at the beginning of January 1945, when the ground would have been frozen, Operation Veritable, the 21st Army Group's advance to the Rhine, was delayed for five weeks by the German Ardennes Offensive. It was therefore conducted over muddy and sometimes flooded ground, and roads were sometimes impassable even to four-wheel-drive vehicles. The offensive was supported by 600 field and 300 medium guns. Over 2.5 million rounds of 25-pounder ammunition were made available. The army roadheads were mainly supplied by rail. Fuels were brought by tankers and the Operation Pluto pipeline from the UK, and delivered by barge and pipeline to the army roadheads. Special arrangements were made to supply the Royal Air Force's Fog Investigation and Dispersal Operation, which consumed 410,000 litres (90,000 imp gal) a night, and the Gloster Meteor jet fighters, which consumed 14,000 litres (3,000 imp gal) of kerosene each day. Montgomery's armies were reinforced by the redeployment of three divisions from Italy under Operation Goldflake.

The next major operation was Operation Plunder—the assault crossing of the Rhine on 23 March. For this the British Second Army and the US Ninth Army deployed 2,144 field and medium guns, augmented by 3,337 anti-aircraft guns and anti-tank guns. A large force of engineer units was assembled for the operation: 37,000 British and Canadian engineers and pioneers, and 22,000 American engineers. Every available amphibious craft was collected, and they were joined by a Royal Navy contingent of 36 LCMs and 36 LCVPs that were transported by road across Holland and Belgium to participate. Operation Plunder included an airborne operation, Operation Varsity, in which two airborne divisions were landed with a day's supply of food, fuel, and petrol. Engineers soon had bridges in operation over the Rhine that were later superseded by more permanent road and rail bridges.

During the first three weeks of April 1945, the 21st Army Group advanced about 320 kilometres (200 mi) across northern Germany to reach the Elbe on 19 April and then the Baltic Sea. Until the railway bridges could be brought into operation, maintenance and support depended entirely on road transport. The 21st Army Group allocated further road transport capacity to the armies by shifting vehicles from the rear areas and immobilising units that were not immediately needed. The corps sometimes had to send their transport back to the army roadheads to assist when major operations were required. The heavy use of road transport meant that the Second Army burned 7,600 tonnes (7,500 long tons) of petrol a day, but pipelines were laid across the Rhine at Emmerich and were in operation by the end of April. On 4 May, Montgomery took the surrender of the German forces in front of the 21st Army Group.

Background

[edit]

The 21st Army Group was commanded by Field Marshal Sir Bernard Montgomery. It consisted of two armies: the First Canadian Army under General Harry Crerar and the British Second Army under Lieutenant-General Sir Miles Dempsey. Most of its units were British or Canadian, but there were contingents from other countries.[1] In mid-March 1945, the 21st Army Group had 1,703 Dutch, 5,982 Czech, 6,696 Belgian, 14,915 Polish, 182,136 Canadian, 328,919 American and 744,361 British servicemen, for a total strength of 1,284,712 personnel.[2] The RAF Second Tactical Air Force, operating in support, also had Australian, French, New Zealand and Norwegian squadrons.[1] Although it contained personnel from many nations, the logistical support was British. Charles Stacey, the Canadian official historian, noted that:

Thus, throughout the campaign in North-West Europe, there was virtually no separate Canadian supply organization other than what existed within First Canadian Army itself. The great majority of Canadian requirements, including ordnance stores, ammunition, petroleum products, most engineer, medical and dental stores, rations, office machinery and other supplies, were provided through British channels. Canadian units indented for warlike stores direct to their division's Ordnance Field Park, which carried stocks of spare parts for mechanical transport, small arms, armament, signal stores, and engineering equipment, as well as complete wireless sets and small arms. Bulk demands for artillery equipment, clothing and general stores were sent periodically by the formation's R.C.O.C. staff to a British Advanced Ordnance Depot.[3]

The 21st Army Group's campaign in North-West Europe had commenced with Operation Overlord, the Allied landings in Normandy on D-Day, 6 June 1944.[4] German resistance was stubborn and the British and Canadian advance much slower than planned until July, when the American Operation Cobra broke through the German defences west of Saint-Lô.[5][6][7] What followed was a far more rapid advance than anticipated.[8] The British Second Army liberated Brussels on 3 September and Antwerp was captured virtually intact on 4 September but it could not be used as a port until the Germans were cleared from the Scheldt approaches, through which ships had to pass to reach the port.[9][10] This required a major operation and the Battle of the Scheldt was not concluded and the port opened for shipping until 26 November.[11] Once it was opened, Antwerp had sufficient port capacity to supply the British and American forces but its use was hampered by German V-weapon attacks.[12]

A new base was developed around Brussels and an advanced base area around Antwerp but supplies were still being drawn from the Rear Maintenance Area (RMA) in Normandy.[12] To get the railway system in operation again required the reconstruction of bridges and the importation of more locomotives.[13] Petrol was brought in by tankers and through the Operation Pluto pipeline from the UK.[14] French, Belgian and Dutch civilian labour was used at the base in a variety of tasks to enable military personnel to be released for service in forward areas. By January 1945, some 90,000 civilians were employed by the 21st Army Group, of whom half were employed in workshops in the advanced base and 14,000 at the port of Antwerp.[15][16] Belgian Army transport units were trained in the UK and took over the equipment of the 17 general transport companies that had been loaned to the 21st Army Group by the War Office in 1944, allowing their personnel to return to the UK.[15]

During the German Ardennes Offensive in December 1944, the Supreme Allied Commander, General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower, had transferred the US First and Ninth Armies to Montgomery's command.[17] Now that the German offensive had been defeated, the US First Army reverted to American command on 18 January 1945 but the US Ninth Army remained part of the 21st Army Group until 4 April.[18] The US XVIII Airborne Corps was assigned to the 21st Army Group for the crossing of the Rhine and again on 25 April for operations between the Elbe and the Baltic Sea.[19][20] Although they were under the operational control of the 21st Army Group, the administrative control of these US formations remained with the US 12th Army Group.[21]

On 31 December 1944, Eisenhower ordered Montgomery to resume his preparations for Operation Veritable, the objective of which was to defeat the German forces west of the Rhine.[22][23] He intended to make the main Allied effort in the north, in the 21st Army Group's sector. There were tactical, operational and political reasons for this. The best sites for a crossing of the Rhine were there, a crossing in the north gave access to the North German Plain, where the terrain was good for mobile warfare, for which his Allied forces were particularly suited, it offered a means of cutting off the Ruhr, the main industrial region of Germany and it had the political advantage of involving the British and Canadians.[24][25][26][27] After some debate, the Combined Chiefs of Staff endorsed his strategy at the Malta Conference in January and February 1945.[28]

Operation Goldflake

[edit]At the Malta Conference, the Combined Chiefs also decided to reinforce Eisenhower's armies in North-West Europe at the expense of those in the Mediterranean. In view of pressure from the Canadian government to have its forces reunited, the Combined Chiefs decided to send the two divisions of the I Canadian Corps to rejoin the First Canadian Army, followed by up to three British divisions.[29] This was codenamed Operation Goldflake, and it involved the redeployment of the I Canadian Corps and British 5th Division from Italy to North-West Europe. At this time the ration strength of the 21st Army Group (which also counts civilians and prisoners of war being fed by the army as well as the troops) was around 1.2 million; that of the Mediterranean theatre was 1.4 million. The transfer involved 102,415 troops. A request from the 21st Army Group for more resources to support the redeployed formations was rejected by the War Office; any further support units required had to either be drawn from the Mediterranean or supplied by the 21st Army Group. To secure the required transportation resources, eleven general transport companies, seven artillery transport platoons, a tank transporter company, a bulk petrol transport company, a bridge company and an ambulance car company were transferred from Italy.[30][31]

To cater for the new arrivals, the 21st Army Group asked for four base supply depots (BSDs), six field bakeries, three field butcheries, a cold storage depot and two detail issue depots (DIDs).[30][a] The Mediterranean theatre was only able to provide two field bakeries. The War Office found that it could provide another two field bakeries from the United Kingdom, along with three field butcheries that were already scheduled to be sent. The other units could not be found, and the 21st Army Group was informed that it would have to make do without them.[30] In May 1945, the 21st Army Group had 25 BSDs, 81 DIDS, 35 field bakeries, and 14 field butcheries.[35]

The headquarters of the 9th Line of Communications Area was transferred to Paris to assist the American Communications Zone with the move.[36] Advance parties from each formation involved travelled by air from Florence, but most Operation Goldflake units moved by sea. It was arranged that 3,700 personnel, 40 tanks, 650 wheeled vehicles and 50 Bren gun carriers would disembark each day in Marseilles, where accommodation was provided for 10,000 troops in tents and parking space for 200 vehicles. The first troops sailed from Naples on the troop ship SS Esperance Bay on 22 February, and arrived at Marseilles two days later. Lorries then took them to the dispersal point at Renaix via Lyon and Dijon, guided by road markers that read "GF". This took another five days.[36][37] The first vehicles to arrive came with only fifty drivers, so a detachment from 141 Vehicle Park was sent to Marseilles from the RMA. In due course it was relieved by a vehicle park from Italy.[38]

A rail halt was established at Gevrey-Chambertin and bivouac areas at Montbard and Chalon-sur-Saône. The bivouac areas were provided with temporary billets, latrines, emergency rations, and fuel, and medical teams and vehicle maintenance crews were on hand. At the rail stop there were messes and a kitchen that ran 24 hours a day. During the two-hour rail halt, the troops were served a hot meal and provided with sandwiches for their next meal. Four trains a day passed through Gevrey-Chambertin, which handled 72,550 personnel and 4,035 lorries. Road transport accounted for another 29,865 personnel and 23,360 lorries.[31]

On 10 February, the 5th Canadian Armoured Division loaded its 450 tanks and 320 Bren gun carriers on flat wagons in Rimini and Riccione, from whence they moved by rail to Leghorn. They were then loaded into landing ships, tank (LSTs) that took them to Marseilles, and onto flat wagons again for the five-day railway journey to Dixmude. Initially Goldflake convoys sailed to Marseilles by a direct route but after the Battle of the Ligurian Sea on the night of 17/18 March they were routed further south, through the Strait of Bonifacio between Corsica and Sardinia.[36][37] Many of the tanks needed overhaul or modification and this task was beyond the resources of the 21st Army Group's Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (REME) units, so excess tanks were shipped to the UK. The problem had been foreseen, and replacements were available at the ordnance depots.[38] All movements were completed by the second week of April.[36][37]

Development of the line of communications

[edit]Fuel

[edit]

At the start of January 1945, the stocks of packaged and bulk POL held by the 21st Army Group amounted to 249,000 tonnes (245,000 long tons), representing 58 days' supply at the normal rate of expenditure. This was more than sufficient to hold the thirty days' reserve of POL that Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) stipulated should be held, but the American fuel position was less favourable. It was therefore agreed that from 1 March 1945 onwards, 74,000 tonnes (73,000 long tons) of fuel, representing about a third of the supply held in British storage, would be transferred to the Americans so both forces could have thirty days' reserves.[39][40]

Ostend was the main reception port for POL. It was linked by pipeline to the largest British POL installation, at Ghent, where there was 50,000 tonnes (50,000 long tons) of storage capacity. Antwerp had 300,000 tonnes (300,000 long tons) of POL storage but that was shared with the Americans.[14] Storage areas for packaged POL (POL in drums or cans as opposed to tanker wagons or lorries)[41] were located at Antwerp, where there was 36,000 tonnes (35,000 long tons); at Diest-Hasselt, where 40,000 tonnes (40,000 long tons) were stored; at Ghent, where 36,000 tonnes (35,000 long tons) were kept; and at Brussels, where there was 20,000 tonnes (20,000 long tons).[14]

The pipeline running from Cherbourg to Rouen was shut down on 9 January, which freed personnel to work on extending other pipelines. The Operation Pluto Dumbo pipeline was now in operation. It drew fuel from Dungeness on the coast of Kent and transported it across the Strait of Dover to a terminal near Boulogne. Pipelines were now constructed from Calais to Ghent, and thence to the storage facilities around Antwerp. By mid-March POL was arriving at a rate of 15,000 tonnes (15,000 long tons) per day, of which 3,000 tonnes (3,000 long tons) was coming over the Dumbo pipeline.[40][42]

The bulk petrol transport companies that distributed the fuel were reorganised, each company now having four instead of three platoons, so eight companies were reduced to six. This saved 150 vehicles, from which a seventh company was formed. At the beginning of March 1945, the 21st Army Group had a bulk petrol transport capacity of about 2,700 tonnes (2,700 long tons) per day, assuming 80 per cent of the vehicles were running. A three-platoon company arrived from Italy with the Operation Goldflake units. A petrol station company was formed from personnel made surplus by the reorganisation with six platoons, each containing three sections. With some assistance from pioneers or civilians, each section could operate a petrol station issuing up to 45,000 litres (10,000 imp gal) per day. As well as the road transport, the 21st Army Group also had barges capable of carrying 10,000 tonnes (10,000 long tons) of bulk POL, which operated on the canals.[40][43] In May 1945, the 21st Army Group had 3 type A, 14 type B and 28 type C petrol depots, a base petrol filling centre, 21 mobile petrol filling centres and 8 bulk petrol transport companies.[35][b]

A major user of fuel was the Fog Investigation and Dispersal Operation (FIDO) system at Épinoy, which consumed 410,000 litres (90,000 imp gal) per night. In February, a French fuel installation was opened at Douai, and this was used to supply the Royal Air Force (RAF) airfields in the vicinity. No. 616 Squadron RAF began operating Gloster Meteor jet fighters from Brussels, and they required kerosene. An initial stockpile of 91,000 litres (20,000 imp gal) was supplied to the unit, followed by daily deliveries of 14,000 litres (3,000 imp gal). A German V-2 rocket scored a direct hit on the British POL installation at Antwerp on 19 January. A train caught alight, and the fire spread to three nearby storage tanks. Although only 3,600 tonnes (3,500 long tons) of petrol was lost, POL storage tanks capable of holding 10,000 tonnes (10,000 long tons) were rendered unusable. As a result of this fire it was decided to remove camouflage from the oil storage tanks, because it was not effective against the V-2, and hampered fire fighting efforts.[40][46]

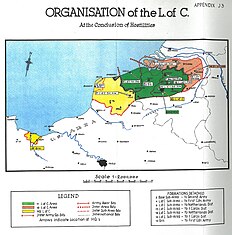

Organisation

[edit]To free up administrative units to support the advance into Germany, it was decided to shorten the line of communications by closing down the RMA in Normandy, where some 300,000 tonnes (300,000 long tons) of supplies were still held. This included 15,000,000 rations, which were gradually eaten by the troops in the RMA. Stores still required by the 21st Army Group were moved forward to the new advanced base.[12] The first phase of this was the transfer of remaining stores to the advanced base. This had been scheduled to occur on 20 March 1945, but in early February it was brought forward to 20 February. Depots and stocks remaining in the RMA were transferred to the control of the War Office.[36]

On 15 February, the region south of the Seine under British administration by 5th Line of Communications Sub Area and the 101st Beach Sub Area were reduced to the ports of Caen and Ouistreham and the depots around them; that administered by the 9th Line of Communications Sub Area was handed over to the US Communications Zone, as was the region between the Somme and the Seine administered by the 6th Line of Communications Sub Area, except for the city of Amiens. This freed the 9th Line of Communications Sub Area to participate in Operation Goldflake.[36]

It was estimated that seven line of communications sub area headquarters would be required to support the advance into Germany. Only three could be provided by the 21st Army Group: the 5th Line of Communications Sub Area and the 101st Beach Sub Area when released from the RMA, and the 9th Line of Communications Sub Area, when it was no longer required for Operation Goldflake. The War Office therefore created a new headquarters, called the 25th Garrison, to take over the RMA, and four new line of communications sub area headquarters, the 17th, 18th, 19th and 20th.[36]

The 25th Garrison assumed control of the RMA on 2 April, allowing the 5th Line of Communications Sub Area to take over the western part of North Brabant, and the 101st Beach Sub Area, which became the 21st Line of Communications Sub Area, took over the territory west of the Maas. The 17th and 19th Line of Communications Sub Areas assumed responsibility for the region around Lille, allowing the 15th Line of Communications Sub Area to move to the area between the Maas and the Rhine. The 18th Line of Communications Sub Area was formed on 25 April and assigned to the First Canadian Army; the 19th joined the 15th; and the 20th relieved the 4th around Brussels, allowing it to take over the region to the north east of Nijmegen. The 6th Line of Communications Sub Area was earmarked to take over the administration of the port of Rotterdam when it was captured. The 11th Line of Communications Area took over the administration of the ports and the entire advanced base area, freeing the 12th Line of Communications Area headquarters to move forward.[36]

Operation Veritable

[edit]Planning

[edit]

Originally scheduled to start on 12 January 1945, when the ground would have been hard and frozen and off-road vehicle movement possible, Operation Veritable was delayed for five weeks by the Ardennes Offensive. By this time a thaw had set in, and the ground was now soft and muddy, restricting off-road vehicle movement.[47] It would be carried out by the First Canadian Army, which was built up to 449,865 personnel through the addition of many British troops; its ration strength was 476,193.[48]

Operation Veritable would be spearheaded by the five British divisions of Lieutenant-General Sir Brian Horrocks's XXX Corps, and would form part of a giant pincer movement with Operation Grenade, which would be conducted by Lieutenant-General William H. Simpson's US Ninth Army.[49] Operation Veritable was scheduled to commence on 8 February, but the date for Operation Grenade could not be set, as it depended on the capture of dams on the Roer further south by the US First Army.[50] Operation Blackcock, a preliminary operation to clear German forces from the Roer Triangle, was carried out by the XII Corps in January 1945. The position gained along the Roer was then taken over by the US Ninth Army.[51][52]

The artillery fire plan for Operation Veritable called for the widespread use of "pepperpot tactics". Operational research had shown that the number of guns saturating an area was more important than the actual weight of shells fired.[53] Pepperpot tactics involved supplementing the artillery fire with that of anti-tank guns, anti-aircraft guns, mortars and machine guns. This involved a large expenditure of ammunition, including some that were in short supply like ML 4.2-inch mortar rounds and the Mark VIIIz ammunition used by the Vickers machine gun.[54]

The weight of shell employed was still formidable; the fire plan called for 6 tonnes (6 long tons) of shells to be delivered on designated targets, and some would receive up to 11 tonnes (11 long tons).[53] Some 600 field and 300 medium guns supported the operation.[55] The 25-pounders were each provided with another 1,471 rounds in addition to the 206 rounds per gun each regiment normally carried.[56] Over 2.5 million rounds of 25-pounder ammunition were made available.[57] Stocks of ammunition were built up at No. 166 Field Maintenance Centre (FMC) at Veghel and the two Canadian FMCs at Wijchen and Oss. No. 166 FMC was developed from one formerly established there by the VIII Corps, although it had to be expanded as XXX Corps had over 200,000 troops under its command for Operation Veritable. To simplify storage and handling, only ammunition for field, medium and heavy artillery was held at the Canadian FMCs, ammunition for all other weapons was stocked at No. 166 FMC.[58] There were 350 different types of ammunition in all.[56]

No. 166 FMC also held 200 rounds per gun of field, 175 rounds per gun of medium, 175 rounds per gun of heavy and 50 rounds per gun of super-heavy artillery ammunition. Medium and heavy ammunition for units north of the Maas was stockpiled at Wijchen and for those to the south of the Maas at Oss. The former held 200 rounds per gun of medium and 250 rounds per gun of heavy artillery ammunition; the latter held 200 rounds per gun of medium and 150 rounds per gun of heavy artillery ammunition. Both stocked 200 rounds per gun of field artillery ammunition for the entire XXX Corps.[55] The ammunition dumping program was completed by 4 February, by which time 14,400 tonnes (14,200 long tons) of ammunition had been dumped at the gun positions, and 23,100 tonnes (22,700 long tons) at the XXX Corps and II Canadian Corps FMCs.[57] Crerar noted that if the ammunition for Operation Veritable was stacked side-by-side and 1.5 metres (5 ft) high, it would have extend for 48 kilometres (30 mi).[59]

The opening of a railway bridge over the Maas at Ravenstein on 4 February enabled the FMCs to be served by rail. This reduced the pressure on the road network, and also permitted stone for road works to be supplied by rail.[59][60] Some 50 miles (80 km) of new roads were built, and over 400 miles (640 km) of roads were repaired, which required 64,000 tonnes (63,000 long tons) of road metal.[61] In the lead up to Operation Veritable, 446 special trains were run to the First Canadian Army railheads, delivering 349,356 tonnes (343,838 long tons) of supplies, of which around 227,000 tonnes (223,000 long tons) was for Operation Veritable.[57]

Road maintenance was made difficult by the winter weather. Temperatures were as low as −15 °C (5 °F) on 26 January, resulting in firm, frozen ground, but a subsequent thaw caused widespread flooding, and by 5 February a section of the Turnhout-Eindhoven road had become impassable even to four-wheel-drive vehicles. Nearly 50 engineer companies, together with three road construction companies and 29 pioneer companies, were engaged in road maintenance.[59] Four main road routes were available for troop movements, utilising road bridges over the Maas at Grave, Mook and Ravenstein. It was estimated that each could carry 7,000 vehicles per day under frozen conditions and 4,000 per day during a thaw. Operation Veritable required 35,000 vehicle movements, mainly to move XXX Corps units 80 miles (130 km) in nineteen days. To coordinate troop movements between the First Canadian Army and the British Second Army, a joint office known as "Grouping Control" was established.[57] For security reasons, troop movements had to be conducted at night. Despite the weather, all movements were completed as planned by 8 February.[62]

Because it was not anticipated that the advance would be rapid, it was not considered necessary to hold large stocks of petrol, oil and lubricants (POL) in the FMCs, but to ensure that vehicles moving to the assembly areas arrived with full tanks of fuel, a train loaded with petrol was sent to Nijmegen to allow them to be topped off.[63] Rations were moved forward, and 2,318,222 rations were stockpiled for Operation Veritable.[59] As it was thought that vehicle movement in the battle area would be restricted by the weather, terrain and battle damage, units were issued with 14-man "compo" ration packs for up to two-thirds of a formation's strength, and the divisions and independent brigades were also supplied with two-, three- and five-man "AFV" ration packs in case the distribution of compo packs proved to be too difficult. The troops in the assault units were issued with 24-hour ration packs, together with a Tommy cooker and a tin containing tea, condensed milk and sugar, enabling them to brew a hot cup of tea.[63] Each of the assaulting infantry carried five days' supplies, and the armoured divisions carried six. This gave them sufficient petrol to advance for 200 and 180 miles (320 and 290 km) respectively, although no such rapid advance was contemplated; the petrol was to sustain the divisions in operations when the road network became congested with operational traffic.[64]

Special tracks were provided for the Bren gun carriers to prevent skidding on icy roads, but these had to be withdrawn when it was discovered that they caused excessive wear and tear on their suspensions. The tracks of Sherman tanks were equipped with "duck bill" connectors to facilitate advancing across snow and soft ground. These were manufactured locally in Brussels and fitted in REME workshops.[63] Extremely cold conditions persisted into February, and the divisions were issued with Arctic clothing and equipment that had been stockpiled for operations in Norway. A special effort was made to ensure that all units had their full allowance of winter and protective clothing.[63] There was also demand for covered accommodation in the 3,300 bivouacs, and 21st Army Group headquarters released 343 huts and 1,600 45-kilogram (100 lb) tents from its stocks, which were delivered to the railheads around Mill and 's-Hertogenbosch. Covered accommodation was eventually provided for between 300,000 and 400,000 troops.[57]

Thus far in the campaign in North-West Europe, XXX Corps had only served as part of the British Second Army, and it found that maintenance procedures of the First Canadian Army differed from what it had been used to due to the fact that the First Canadian Army's operations had been conducted where there had been adequate communications. Consequently, the daily pack trains that carried supplies were normally run straight through from the advanced base to the corps railheads, each of which normally stocked a particular commodity, such as ammunition, POL or engineer supplies, and the roadheads supporting the First Canadian Army carried much less stock than its British Second Army counterparts. This saved on road transport, but at the cost of some degree of flexibility.[65]

It did not remove the need for road transport entirely though, and XXX Corps found that the First Canadian Army was unable to provide any further resources. Fourteen transport platoons,[65] each of which operated thirty vehicles,[66] were taken from the divisions to serve the corps' needs. The possibility that the Germans might flood the forward area was not overlooked, and a company of DUKW amphibious trucks and a platoon of Terrapin amphibious vehicles was on 48-hours' notice to assist. During February 300,000 tonnes (300,000 long tons) of supplies were delivered to the XXX Corps railheads. Supplies and POL were stocked at Eindhoven; POL at Schijndel; ammunition at Veghel, Uden, Oss and Wijchen; road material at Mill; coal at Best; and bridging at 's-Hertogenbosch.[65]

Execution

[edit]

Once the battle commenced on 8 February, the main administrative task was replenishing the stocks of ammunition. Since the First Canadian Army did not hold large stocks at No. 11 Army Roadhead, it was dependent on the daily arrival of ammunition trains. Daily expenditure of ammunition soon exceeded a trainload, so the non-arrival of even one train meant that ammunition had to be drawn from the Second Army roadhead at Bourg Leopold. Since prompt clearance of the trains was essential to allow turnaround of the locomotives and rolling stock, vehicles had to be used to clear less urgently required supplies such as POL, coal and engineer stores. Ammunition expenditure was prodigious, and a system of rationing had to be introduced. This was never satisfactorily implemented, and confusion and duplication was created by the same requests for more ammunition being made through multiple channels.[67]

Rising floodwaters soon created difficulties. By 9 February sections of the Nijmegen-Kranenburg road were under 46 centimetres (18 in) of water and 8.0 kilometres (5 mi) of the Nijmegen-Cleve road was under 610 millimetres (24 in) of water. DUKWs were employed to move supplies forward along it to a "skeleton" FMC, No. 167 FMC established by the XXX Corps, which held only petrol, compo ration packs and ammunition. To maximise their turnaround time, they were only used to cover the flooded stretch, loads being transferred to them and unloaded from them into other vehicles at each end. Some of the ammunition that had earlier been dumped was rendered inaccessible by rising floodwaters. It was feared for a time that the skeleton FMC was in danger of being inundated, although it was on high ground. Preparations were made to move it to a new site, but this was not required. The 3rd Canadian Division made use of Buffalo tracked amphibious vehicles. In the forward area, land mines and the few tracks through the Reichswald Forest kept vehicles on the roads, and the traffic, thaws and heavy rains resulted in a rapid deterioration of the roads. Recourse was therefore made to Weasel tracked vehicles, and every available Weasel was rushed to the front. Many had seen hard use in the Ardennes, where they had demonstrated their utility, and large numbers were in the REME workshops. An emergency repair effort was conducted, and many were shipped direct from the workshops to the front lines.[67]

The II Canadian Corps assumed control of the left sector on 15 February and No. 167 FMC was handed over to it, becoming No. 206 FMC. XXX Corps opened a new No. 168 FMC near Goch. The XXX Corps FMC series started at 151 and the II Canadian Corps one started at 201, and the stark difference in maintenance practices between the two corps was illustrated by the fact that XXX Corps had opened three times as many FMCs in the campaign up to this point. When the flood waters subsided, it was found that the Nijmegen-Cleve road surface had been too badly damaged to use, so the II Canadian Corps and XXX Corps were forced to share the road running south of the Reichswald. XXX Corps reverted to the control of the British Second Army on 8 March, and by 10 March the last German units had retreated across the Rhine. The two corps stocked their FMCs by road, but the completion of repairs to the 1,222-metre (4,008 ft) bridge over the Maas at Gennep by the 7th Army Troops Engineers on 20 March relieved the pressure on the one at Grave, and it became possible to move the railhead to within the No. 168 FMC area at Goch.[67][68][69]

Operation Plunder

[edit]Planning

[edit]

With Antwerp in operation from 26 November 1944, some supplies were now coming directly from the United States. The longer shipping time meant that a working margin of 30 days' supplies was desirable instead of the 14 days' margin for shipments from the United Kingdom. It was anticipated that as the Allied advance proceeded into Germany, there would be increased demand to feed and accommodate prisoners of war, liberated Allied prisoners and displaced persons. Having more reserves would also allow transport to be temporarily diverted from port clearance to support a rapid advance, as had been done the previous autumn. A request for an increase in the theatre reserves from 28 to 51 days was approved by the War Office, but it was not possible to increase the stockpile of ammunition, as this was already being shipped as fast as it could be manufactured.[70]

The next major operation was Operation Plunder—the assault crossing of the Rhine. For this the British Second Army deployed 1,520 field and medium guns, and the US Ninth Army had 624 field and medium guns. They were respectively augmented by 1,891 and 1,446 anti-aircraft guns and anti-tank guns.[71][72] Ammunition for the 25-pounders was based on 1,500 rounds per gun.[72] In the three days preceding the assault, the three hundred and thirty six 25-pounders assigned to the XII Corps fired 225,061 rounds, the sixteen 4.5-inch guns fired 7,002 rounds, the one hundred and sixty 5.5-inch guns fired 69,607 rounds, the fifty two 155 mm howitzers fired 4,335 rounds, the sixteen 7.2-inch howitzers fired 3,964 rounds, and the two 8-inch howitzers fired 176 rounds. Also, XII Corps employed forty-eight 3.7-inch anti-aircraft guns in the ground role, and they fired 16,573 rounds.[73] Up to seven trains per day were required to move the ammunition from the advance base to the ammunition railheads at No. 10 Army Roadhead. Deliveries of ammunition averaged 4,800 tonnes (4,700 long tons) per day, peaking at 9,300 tonnes (9,150 long tons) on 25 March. A smoke screen concealed preparations on the west bank of the Rhine. Demands for smoke generators exhausted the available stocks and generators were taken from the anti-aircraft gun positions around Antwerp.[38]

A large force of engineer units was assembled for the operation: 37,000 British and Canadian engineers and pioneers, and 22,000 American engineers.[72] Every available amphibious craft was collected. As well as the storm boats, DUKWs, Buffaloes and Weasels,[74] there were also amphibious DD tanks. The Royal Navy formed Force U, consisting of three squadrons, each with a flotilla of twelve Landing Craft Medium (LCM), and a flotilla of twelve Landing Craft, Vehicle, Personnel (LCVP), which were transported by road across Holland and Belgium to participate.[75][76] When mounted on the proposed trailer, the 15-metre (50 ft) LCM was 4.6 metres (15 ft) high, which left only 7.6 centimetres (3 in) of clearance under some of the bridges they had to pass under between Antwerp and the staging area around Nijmegen. The base workshops built a prototype trailer that provided more clearance, and the navy ordered 25 of them. Five days before the operation began, the navy asked for 40 more, which were provided. The Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers and the Buffalo tracked amphibious vehicles of the 79th Armoured Division were overhauled between January and March.[77]

The accumulation of stocks for Operation Plunder began on 8 March. During the month, 432 trains delivered 230,000 tonnes (230,000 long tons) to 37 railheads in the British Second Army area.[78] The British rail line of communications now ran from Antwerp to Nijmegen via Roosendaal and Tilburg,[79] where the railway bridge that had opened on 22 December was duplicated by 3 January 1945.[80] By the time the amphibious phase of Operation Plunder commenced at 09:00 on 23 March,[81] 60,000 tonnes (60,000 long tons) of ammunition, 18,000 tonnes (18,000 long tons) of POL, 5,000 tonnes (5,000 long tons) of supplies, 30,000 tonnes (30,000 long tons) of engineer stores and 5,500 tonnes (5,400 long tons) of other stores had been dumped at No. 10 Army Roadhead. Second Army's VIII, XII and XXX Corps drew their supplies from No. 10 Army Roadhead, and the attached II Canadian Corps continued to draw its supplies from the First Canadian Army's No. 13 Army Roadhead at Nijmegen.[75]

Units participating in Operation Plunder were re-equipped before the start of the operation. A special train brought the required stores to the Second Army railhead within 48 hours of a demand being lodged with the advance base. A problem was encountered when defects were discovered in the tensioners of the 29th Armoured Brigade's new Comet tanks. A new type was flown out direct from the UK factory by priority air-freight and fitted to the tanks. The British 6th Airborne Division was withdrawn to the UK and re-equipped there, but the logistical units of its seaborne tail had to be re-equipped by the 21st Army Group. This was difficult as its special equipment was not stocked. A new ordnance field park was formed to hold the equipment, which was shipped from the UK.[38]

Execution

[edit]

The two airborne divisions participating in Operation Varsity, the airborne operation supporting Operation Plunder, were initially supplied by the First Allied Airborne Army.[75] Their initial drop of the 6th Airborne Division was conducted by 683 aircraft and 444 General Aircraft Hamilcar and Airspeed Horsa gliders; that of the US 17th Airborne Division used 913 aircraft and 906 Hadrian gliders. Fifteen minutes after the glider landings, there was a resupply mission flown by 240 Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers from the US Eighth Air Force.[82] Of the 610 tonnes (600 long tons) of supplies and equipment dropped, 80 per cent was recovered. Sixteen of the bombers were lost to anti-aircraft fire.[83] The supplies dropped represented a day's supply of food, fuel, and petrol for the two divisions.[74]

Once the link-up with the ground forces was effected, the 6th Airborne Division drew its supplies from XII Corps, and the US 17th Airborne Division drew its from the US Ninth Army.[75][84] The seaborne tail of the 6th Airborne Division established a DUKW replenishment area west of the Rhine from whence supplies were moved until it could cross the river.[74] XII Corps allocated sixty DUKWs each to the 6th Airborne Division, US 17th Airborne Division and the 15th Infantry Division; thirty were in corps reserve, nine were designated for casualty evacuation and six for the Royal Engineers.[85] In XXX Corps, all DUKWs were retained under corps control.[86]

The South Beveland Canal was opened on 19 February to allow inland water transport to reach the Dutch canal system when the western Netherlands were liberated. The Meuse-Escaut Canal was also opened that month, and by the end of March the Zuid-Willemsvaart and the Maas–Waal Canal were open as well, allowing barge traffic from Antwerp to reach the Waal. The average tonnage on the canal system rose steadily from 27,000 tonnes (27,000 long tons) in January to 35,000 tonnes (34,000 long tons) in February, 48,000 tonnes (47,000 long tons) in March and 56,000 tonnes (55,000 long tons) in April.[87][78] The road network was also developed, and by 23 March eleven routes were open across the Maas, of which six were in the First Canadian Army area, including the sole class 70 route (i.e. one roughly capable of bearing loads of up to 71 tonnes (70 long tons)) and five in the British Second Army area. The British Second Army also had access to the American class 70, timber pile bridge at Venlo and the Canadian First Army class 70 bridge at Grave. Only the class 70 bridges would take a loaded tank transporter.[78][88]

At Gennep, the 6th Army Troops Engineers built a 312-metre (1,023 ft) class 30 Bailey bridge using the piers and abutments of a demolished railway bridge. A 229-metre (751 ft) class 40 Bailey pontoon bridge was erected by the 7th Army Troops Engineers at Well and a 270-metre (880 ft) one by the 6th Army Troops Engineers at Lottum was opened for traffic on 10 March.[89] A 370-metre (1,220 ft) class 40 Bailey pontoon bridge was built at Venlo by the 15th GHQ Troops Engineers.[90] These bridges carried maintenance traffic by day and operational traffic by night.[91] Seven American combat engineer battalions assisted with road and bridge maintenance in the British Second Army area.[92] Although working in the British Second Army area, they remained under the command of the US Ninth Army.[90] The 21st Army Group headquarters also allocated three other general transport companies to the British Second Army.[75] The final troop movements for Operation Plunder involved 662 tanks, over 4,000 tank transporters and 32,000 other vehicles.[91]

Vehicles crossing the Rhine did so with full fuel tanks and a reserve of filled jerricans. Additional fuel supplies were loaded on DUKWs, to be ferried across the river until bridges were opened. Each man crossing the Rhine was issued with a 24-hour ration and an emergency ration, plus a tin of preserved meat, a tin of self-heating soup or cocoa, a packet of biscuits and a Tommy cooker with six hexamine tablets. Divisions carried two days' compo rations in their first line (unit) transport and two days' in their second line (divisional) transport. The armoured divisions also carried a day's worth of AFV ration packs. The airborne troops landed with two 24-hour ration packs, and the 6th Airborne Division's seaborne tail held two days of compo rations in second line transport. A double issue of Expeditionary Force Institutes stores was made to all participating units. This included the 6th Airborne Division, but it was held by the seaborne tail.[85]

The assault divisions established ordnance dumps on the west bank of the Rhine with at least one section of the divisional ordnance field park from which urgently required equipment and spare parts for vehicles could be sent across by DUKW without delay. Damaged vehicles on the east bank of the Rhine were collected at points near the river and transported back on rafts.[85] XII and XXX Corps each formed a bank control group along the lines of the beach groups that had supported the Normandy landings in 1944, but with the logistical elements restricted to the medical, provost and REME components. The bank control groups controlled all movement from the marshalling areas on the near side of the Rhine to the dispersal areas on the far side. They only operated until newly constructed bridges were able to take traffic, which occurred about 72 hours into the operation.[72]

The engineer units in the XII Corps assault area were under 11th Army Group, Royal Engineers (AGRE), commanded by Colonel R. B. Foster.[93] The XII Corps plan called for the construction of a class 9 Folding Boat Equipment (FBE) bridge, a class 12 Bailey pontoon bridge and two class 40 Bailey pontoon bridges. The first British bridge across the river was the class 9 FBE bridge, known as "Twist", in the XII Corps area, which was erected by the VIII Corps Troops Engineers in ten hours on 24 March. A traffic jam broke the bridge during the night, but it was reopened thirteen hours later. The class 12 Bailey bridge, known as "Sussex", took the XII Corps Troops Engineers and the Royal Navy 43 hours to erect. Meanwhile, the class 40 Bailey pontoon bridge at Xanten was erected by the 7th Army Troops Engineers in 31 hours, and opened to traffic at 16:30 on 25 March. Over the next six days it was used by 29,139 vehicles. The second class 40 Bailey pontoon bridge, "Sparrow", was built by the 4th GHQ Troops Engineers on 27 March.[94][95]

In the XXX Corps area, the engineer units were grouped under the 13th AGRE, under the command of Colonel F. C. Nottingham.[93] The XXX Corps plan called for the construction of a class 9 FBE bridge, a class 15 Bailey pontoon bridge and two class 40 Bailey pontoon bridges. The "Waterloo" class 9 FBE could not be built at the intended site at Rees on 24 March because the town had not been captured. Instead, 18th GHQ Troops Engineers erected it the following day at a downstream site near the town of Honnopel. Work commenced at 09:30, and the bridge was opened for traffic at midnight. Bridges were named after ones in London. The XXX Corps Troops Engineers commenced work on "Lambeth", a class 15 Bailey pontoon bridge, at 15:00 on 24 March, but work was frequently interrupted by German fire, and the bridge was not opened until 08:30 on 26 March. Due to the proximity of Rees, the VIII Corps Troops Engineers could not work on "London", a class 40 Bailey pontoon bridge, until the afternoon of 25 March, and it was opened at 23:00 on 26 March. The second class 40, Bailey pontoon bridge, known as "Blackfriars", was built by the II Canadian Corps Engineers in 50 hours, starting at 10:00 on 26 March. A third bridge, called "Westminster", was commenced by the 6th Army Troops Engineers on 26 March, completed at 18:00 on 29 March, and ceremoniously opened by Dempsey the next morning.[94][96]

It was recognised in the planning of Operation Plunder that the maintenance of the floating bridges over the Rhine would require more engineers than could be spared from the campaign ahead. It was therefore decided that the floating bridges should be replaced by semi-permanent ones as soon as operational circumstances permitted. It was estimated that six one-way class 40 and two one-way class 70 pile bridges would be needed. Their construction would require 3,000 wooden piles 30 centimetres (12 in) in diameter and 18 to 23 metres (60 to 75 ft) in length. To provide them, beech trees were felled in the Sonian Forest near Brussels. Some 10,000 tonnes (10,000 long tons) of wooden piles, baulks and chesses was assembled for the project. These included 36-centimetre (14 in) baulks and chesses that had originally been set aside for the construction of emergency bridges over the Thames. Twenty-five special vehicles were built in Army workshops to carry them. Due to changing operational requirements, it was ultimately decided to build only three semi-permanent class 40 bridges, at Xanten, Rees and Arnhem, and two class 70 bridges, at Rees and Arnhem.[97]

A semi-permanent class 40 bridge and a semi-permanent class 70 bridge were also built over the IJssel at Zutphen. The class 40 timber pile bridge at Zanten, known as "Dempsey" was built by the 18th GHQ Troops Engineers and was opened on 26 May.[98] At Rees, steel-piled class 40 and class 70 jetty bridges 490 metres (1,600 ft) long and known as "Tyne" and "Tees" were built by the 50th GHQ Troops Engineers, and were opened on 23 May. The 690-metre (2,250 ft) class 40 and 70 steel-piled jetty bridges were built at Arnhem by the First Canadian Army engineers, and opened on 31 May, and the 440-metre (1,450 ft) class 40 and class 70 timber pile bridges at Zutphen were completed on 26 May.[97]

Beyond the Rhine

[edit]During the first three weeks of April 1945, the Second Army advanced about 320 kilometres (200 mi) across northern Germany to reach the Elbe on 19 April. During this advance it suffered 7,665 casualties and captured 78,108 prisoners. Until the railway bridges could be brought into operation, maintenance depended entirely on road transport.[99] The 21st Army Group allocated an additional 2,190 tonnes (2,160 long tons) of road transport capacity to the Second Army between 27 March and 3 April. Another 640 tonnes (630 long tons) was reallocated from the First Canadian Army, and 7+1⁄2 platoons were made available, taking the transport from an anti-aircraft brigade.[100] Another 2,000 tonnes (2,000 long tons) was obtained from within the Second Army by taking transport from artillery and armoured units that were not immediately required for the advance.[99]

Stocking of No. 12 Army Roadhead in the Rheine area commenced on 3 April, and VIII, XII and XXX Corps started drawing from it on 9 April. Between 6 and 8 April the 21st Army Group released another 4,630 tonnes (4,560 long tons) of road transport, along with two DUKW companies that were re-equipped with 3-ton trucks. This came from the reorganisation of the line of communications, and more general transport companies arriving from Italy through Operation Goldflake. Stocking of No. 14 Army Roadhead in the Sulingen area from No. 10 Army Roadhead commenced on 13 April, and the first train arrived at No. 12 Army Roadhead via the American rail bridge at Wesel three days later. Three trains a day were run over this route under an arrangement with SHAEF and the American Military Railway Service.[101][102]

That day trains also began arriving at No. 16 Army Roadhead from locations around Bocholt, using captured rolling stock and locomotives. German railway personnel were used to man two trains a day from Celle to Bienenbuttel. They were also utilised for duties such as manning level crossings. The expansion of the rail network allowed the 21st Army Group to give the Second Army another 11,460 tonnes (11,280 long tons) of road transport capacity. Railway units were moved forward, and only one railway group headquarters and two railway operating companies were left in France, Belgium and the Netherlands south of the Waal.[101][102]

Despite this, stocks at the Nos. 12 and 14 Army Roadheads were being run down. On 16 April XXX Corps sent its road transport back to the Rhine roadhead to collect the ammunition it needed to capture Bremen. There were doubts as to whether this need could be met, but the situation was eased by the arrival of 4,700 tonnes (4,600 long tons) of ammunition that had been pre-loaded on some of the transport allocated by the 21st Army Group. Three days later, XII Corps did the same to facilitate the capture of Hamburg, but the expenditure of ammunition at Bremen was not as great as anticipated, and this allowed XII Corps' requirements to be met in full. VIII Corps also used its own transport to haul ammunition for the crossing of the Elbe on 28 April.[99][100]

A 300-metre (980 ft) Class 9 FBE bridge was built over the Elbe at Lauenburg by the VIII Corps engineers on 29 April. While it was under construction, the engineers came under attack by the Luftwaffe, and 8 men were killed and 22 wounded. This merely delayed work on the bridge, which was opened to traffic at 20:15. The following day a German swimmer was seen affixing a suspicious cylindrical object to the bridge. The object sank after being cut loose during an attempt to recover it, and the swimmer was captured.[103] At Artlenburg, 7th Army Troops engineers constructing a 282-metre (925 ft) class 40 Bailey pontoon bridge also came under air attack, and two of its mobile cranes were damaged by artillery fire, but the bridge was opened on schedule at 12:00 on 30 April. Over the next 24 hours, 7,415 vehicles crossed the bridge.[103]

On 3 May an VIII Corps FMC at Lüneburg was taken over by the Second Army and used as an advance roadhead in conjunction with No. 14 Army Roadhead.[104] There was a further allocation of 5,100 tonnes (5,000 long tons) of road transport for the drive to the Baltic Sea on 26 April, and another 2,700 tonnes (2,700 long tons) was received by the end of the month. This brought the amount of road transport capacity under Second Army's control to 31,580 tonnes (31,080 long tons), which was reckoned to be the equivalent of 76 general transport companies.[100][101] The high use of road transport meant that the Second Army was burning 7,600 tonnes (7,500 long tons) of petrol a day, but the supply of fuel caused no problems. The Dumbo pipeline was extended from Boulogne to Antwerp in March. Two pipelines were laid across the Rhine at Emmerich and were in operation by the end of April. Initially, bulk POL was brought across the Rhine in tanker trucks at the rate of 1,000 tonnes (1,000 long tons) per day. It was decanted at Bocholt and transported by rail to No. 14 Army Roadhead. By mid-May the 21st Army Group's reserves had been reduced by a quarter.[100][105]

Dumbo surpassed its target of 4.5 million litres (1 million imperial gallons) (about 3,620 tonnes (3,560 long tons)) per day on 15 March 1945, and by 3 April the Dumbo lines were delivering 4,600 tonnes (4,500 long tons) a day.[106] New lines continued to be laid, the last one on 24 May.[107] By this time the system consisted of 1,811 kilometres (1,125 mi) of pipelines and storage tanks with a capacity of 104,770 tonnes (103,120 long tons).[108] To take pressure off the roads, the 21st Army Group placed an air composite platoon capable of receiving and handling up to 510 tonnes (500 long tons) per day under the Second Army's control. An allocation of 300 tonnes (300 long tons) per day was made, but owing to competing American demands, the use of aircraft to repatriate liberated American, British and Commonwealth ex-prisoners of war (PWX), and a somewhat cumbersome procedure for requesting air deliveries, the tonnage of air freight never reached this level, averaging just 145 tonnes (143 long tons) per day for the month of April. British and Commonwealth PWX were flown directly to the UK, and American PWX were flown to collecting camps around Le Havre.[100][104][109]

Meanwhile, the First Canadian Army established two lines of communications. No 13 Army Roadhead was opened at Nijmegen on 2 March, and was stocked by rail. No. 15 Army Roadhead opened in the Almelo area on 18 April being stocked by road from the No. 13 Army Roadhead. I Canadian Corps advanced on Utrecht, supported by No. 13 Army Roadhead while II Canadian Corps advanced on Oldenburg supported from No. 15 Army Roadhead. Emmerich was taken on 1 April after a three-day battle, to provide another bridgehead. Three bridges were constructed there, but by the time they opened II Canadian Corps already had its three Canadian divisions across the Rhine.[84][110]

As the German forces crumbled before the Allied onslaught, the numbers of German prisoners of war grew to the point where orders were issued on 1 May that no more prisoners should be sent west of the Rhine. Four days later orders came that disarmed troops would no longer have prisoner of war status, but would be classified as Surrendered Enemy Personnel, and that their own officers would be responsible for their administration. Captured German dumps held sufficient quantities of food for them, but they were not always easily accessible or distributable, so some had to be fed from 21st Army Group stocks, on a temporary ration scale of 1,100 calories (4,600 J) per man per day. Large numbers of displaced persons were also encountered, and they were accommodated in special camps. These provided health care, bathing and delousing with DDT to prevent the spread of disease. Their feeding was the responsibility of the German civilian population, but the British Army had to release many NAAFI packs to displaced persons.[111] By May the ration strength of the 21st Army Group had risen to 1.711 million.[112]

On 4 May 1945, Montgomery accepted the German surrender at Lüneburg Heath, which covered German forces in the Netherlands, Dunkirk, North-West Germany and Denmark. Four days later the German Instrument of Surrender was signed in Berlin, and the war with Germany was over.[113]

Post-war

[edit]Civil affairs supplies (mostly food, but also soap, medical supplies and some other goods for civilian use) were issued through military channels.[114] The British Occupation zone in Germany roughly corresponded to the old Prussian provinces of Schleswig-Holstein, Hanover and Westphalia, together with the northern half of the Rhine Province. Each of the three areas was controlled by a corps.[115] Major-General Gerald Templer became the Director-General of Civil Affairs at 21st Army Group headquarters in March 1945.[116] He recognised that a humanitarian catastrophe was in the making in Germany unless food, shelter and fuel could be made available to the civilian population.[117]

The British zone contained the Ruhr, and its agricultural areas, mostly devoted to dairy farming, were insufficient to feed the population. Before the war it had imported millions of tons of food from the eastern parts of Germany which were now in the Soviet occupation zone, but the collapse of the transportation system caused by Allied bombing had prevented the movement of foodstuffs, mostly grain and potatoes, in the 1944–1945 agricultural season, and stocks were all but exhausted. Even butter production was at a standstill owing to a shortage of coal.[118]

Rehabilitation of Germany's transportation infrastructure was a priority. Regional port control organisations were established at Emden, Hamburg and Lübeck, and inland water control teams at Hamburg, Hanover, Münster and Duisburg. Most of the senior staff of the Reich Ministry of Transport were discovered on a pair of trains in the Hamburg area. Finding staff for the British control organisations was more difficult, as demobilisation and redeployment for the ongoing war against Japan thinned the ranks of skilled transportation officers.[119]

The railway system required considerable work. A major bottleneck was the line between Löhne and Hanover, because there was only a single-track bridge over the Weser near Bad Oeynhausen. Another single-line bridge was opened in August 1945. Rolling stock was recovered from damaged rail yards and in some cases tank transporters were used to move wagons from sections of the line that had become isolated due to damaged bridges. By October about 22 per cent of the railways were back in service.[119] Road transport was no less hampered by the loss of bridges, and the Royal Engineers took the lead in repairing or replacing the 1,500 bridges that had been destroyed by bombing or demolitions. To get the vehicles back into service, the REME organised 530 workshops by the end of July. Initially trams were preferred to buses to economise on petrol and tyres, but by September the focus had shifted to conserving coal.[119]

The British zone had sources of coal, but the number of miners had fallen from around 300,000 before the war to 117,000 in June 1945, due to the departure of foreign workers, the German miners who had been drafted into the army, and the dispersal of the local population due to bombing and fighting. The 21st Army Group organised the effort to get the coal industry working again. As well as a shortage of labour, there was a shortage of wooden pit props. Arrangements were made to acquire 1,500 tonnes (1,500 long tons) per day from the American zone, but this did not meet the requirement of 3,600 tonnes (3,500 long tons). The British Army organised the extraction of the rest from the British zone, despite its dearth of forests, and timber was brought to the mines by British Army transport.[120]

Outcome

[edit]In the campaign in North-West Europe in 1945, Montgomery sought to contribute to the defeat of Germany and to do so in a manner that displayed a visibly committed and active British role. He had to do so to ensure a prominent British role in the post war political organisation of Europe and secure a stable and lasting peace. This was not easy when the 21st Army Group was fighting alongside the much larger American armies and had to deal with a severe manpower shortage. Excessive casualties could reduce the size of the British force and hence its role and visibility. To compensate for this, to minimise casualties, and to maximise the combat effectiveness of what manpower they had, the British forces relied on machines, materiel and firepower.[121][122]

The vast resources brought to bear were in stark contrast with scarcities of the early war years.[123] Lend-Lease aid from the United States and a high degree of industrial mobilisation provided the equipment and materiel. The British Army of 1944–1945 was highly mechanised, which conferred great tactical and strategic manoeuvrability, but at the same time demanded a high degree of organisation and professionalism to use the machines, materiel and firepower to best effect.[124] In this campaign the British Army demonstrated its proficiency in logistics.[123] The 21st Army Group's logistical system proved capable of keeping the fighting men fed and supplied, whether in the awful weather conditions of Operation Veritable or the fast-moving advance of the final drive beyond the Rhine.[125]

Notes

[edit]- ^ A BSD was a unit capable of supplying up to 25,000 troops. It had four store sections.[32] A field bakery had 56 personnel and could produce up to 16,000 kilograms (35,000 lb) of bread per day. A DID was a 31-man unit capable of supplying up to 8,000 troops. It had a supply section and a petrol, oil and lubricants (POL) section.[33][34]

- ^ A petrol depot was a unit that received, stored and issued package petroleum products. There were three types: type A, which had 85 personnel and was designed to hold up to 12,700 tonnes (12,500 long tons); type B, with 38 personnel, which was designed to hold up to 5,100 tonnes (5,000 long tons); and type C, with 24 personnel, which was designed to hold up to 2,000 tonnes (2,000 long tons). With the good road and rail communications and civilian labour available, as was often the case in North-west Europe, they often held far more.[44][45]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Ellis & Warhurst 1968, pp. 367–371, 389–391.

- ^ MacDonald 1973, p. 297.

- ^ Stacey 1960, p. 624.

- ^ Buckley 2014, p. 47.

- ^ Carter & Kann 1961, p. 278.

- ^ Pogue 1954, p. 199.

- ^ Ruppenthal 1953, pp. 475–478.

- ^ Carter & Kann 1961, pp. 296–297.

- ^ Ellis & Warhurst 1968, pp. 4–6.

- ^ Buckley 2014, pp. 200–202.

- ^ Ellis & Warhurst 1968, p. 127.

- ^ a b c Carter & Kann 1961, pp. 333–335.

- ^ Carter & Kann 1961, pp. 336–337.

- ^ a b c Carter & Kann 1961, pp. 339–340.

- ^ a b Carter & Kann 1961, pp. 340–341.

- ^ Donnison 1961, p. 121.

- ^ Ellis & Warhurst 1968, pp. 182–183.

- ^ Ellis & Warhurst 1968, pp. 196, 301.

- ^ Ellis & Warhurst 1968, pp. 285–291.

- ^ Ridgway 1945, p. 1.

- ^ Landon 1945, p. 52.

- ^ Ellis & Warhurst 1968, p. 204.

- ^ Montgomery 1958, pp. 320–321.

- ^ Ruppenthal 1959, p. 372.

- ^ MacDonald 1973, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Essame & Belfield 1962, p. 80.

- ^ Stacey 1960, p. 307.

- ^ Pogue 1954, pp. 409–416.

- ^ Nicholson 1956, pp. 658–660.

- ^ a b c Boileau 1954a, p. 367.

- ^ a b Lord et al. 1945, p. 112.

- ^ Boileau 1954b, p. 311.

- ^ Boileau 1954a, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Boileau 1954b, p. 312.

- ^ a b Boileau 1954b, p. 385.

- ^ a b c d e f g h 21st Army Group 1945, p. 96.

- ^ a b c Nicholson 1956, p. 660.

- ^ a b c d 21st Army Group 1945, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Carter & Kann 1961, pp. 339–340, 360.

- ^ a b c d 21st Army Group 1945, pp. 111–112.

- ^ "Bulk vs. Non-Bulk Packaging". Royal Chemical. 8 February 2021. Retrieved 13 June 2023.

- ^ Carter & Kann 1961, pp. 259–261.

- ^ Boileau 1954a, p. 364.

- ^ Boileau 1954a, p. 54.

- ^ Boileau 1954b, p. 332.

- ^ Boileau 1954a, p. 366.

- ^ Essame & Belfield 1962, p. 82.

- ^ Stacey 1960, p. 457.

- ^ Buckley 2014, pp. 268–269.

- ^ Stacey 1960, pp. 456–457.

- ^ Ellis & Warhurst 1968, pp. 241–242.

- ^ Carter & Kann 1961, pp. 346–347.

- ^ a b Buckley 2014, p. 272.

- ^ Carter & Kann 1961, pp. 350–351.

- ^ a b Carter & Kann 1961, p. 350.

- ^ a b Stacey 1960, p. 458.

- ^ a b c d e 21st Army Group 1945, p. 101.

- ^ Carter & Kann 1961, pp. 349–350.

- ^ a b c d Stacey 1960, pp. 457–458.

- ^ Inglis 1945, p. 57.

- ^ Buchanan 1953, p. 188.

- ^ Carter & Kann 1961, pp. 352–353.

- ^ a b c d Carter & Kann 1961, p. 351.

- ^ Carter & Kann 1961, p. 353.

- ^ a b c Carter & Kann 1961, p. 349.

- ^ Boileau 1954a, p. 61.

- ^ a b c Carter & Kann 1961, pp. 353–357.

- ^ Carter & Kann 1961, p. 361.

- ^ Inglis 1945, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Carter & Kann 1961, p. 360.

- ^ Stacey 1960, pp. 532–533.

- ^ a b c d Carter & Kann 1961, p. 364.

- ^ Carter & Kann 1961, p. 366.

- ^ a b c Carter & Kann 1961, p. 365.

- ^ a b c d e Carter & Kann 1961, p. 363.

- ^ Stacey 1960, p. 535.

- ^ 21st Army Group 1945, pp. 115–116.

- ^ a b c Carter & Kann 1961, p. 362.

- ^ Micklem 1950, p. 149.

- ^ Inglis 1945, p. 87.

- ^ Stacey 1960, pp. 534–535.

- ^ Otway 1990, pp. 304–306.

- ^ Ellis & Warhurst 1968, p. 291.

- ^ a b Stacey 1960, p. 628.

- ^ a b c Carter & Kann 1961, pp. 366–367.

- ^ Carter & Kann 1961, p. 368.

- ^ 21st Army Group 1945, p. 100.

- ^ Inglis 1945, p. 51.

- ^ Inglis 1945, pp. 56–57.

- ^ a b Pakenham-Walsh 1958, p. 475.

- ^ a b Ellis & Warhurst 1968, p. 287.

- ^ Ellis & Warhurst 1968, p. 286.

- ^ a b Pakenham-Walsh 1958, p. 482.

- ^ a b Pakenham-Walsh 1958, pp. 500–502.

- ^ Inglis 1945, p. 67.

- ^ Inglis 1945, pp. 113–114.

- ^ a b Buchanan 1953, pp. 189–190.

- ^ Inglis 1945, pp. 149–153.

- ^ a b c Ellis & Warhurst 1968, p. 312.

- ^ a b c d e Boileau 1954a, p. 373.

- ^ a b c 21st Army Group 1945, pp. 102–103.

- ^ a b Micklem 1950, p. 150.

- ^ a b Inglis 1945, pp. 185–187.

- ^ a b Carter & Kann 1961, pp. 371–373.

- ^ 21st Army Group 1945, pp. 112–113.

- ^ Krammer 1992, pp. 461–462.

- ^ Payton-Smith 1971, pp. 447–448.

- ^ Carter & Kann 1961, p. 372.

- ^ Field 1966, p. 820.

- ^ Ellis & Warhurst 1968, pp. 313–314.

- ^ Carter & Kann 1961, pp. 373–374.

- ^ Boileau 1954b, p. 418.

- ^ Fraser 1983, p. 395.

- ^ Donnison 1961, pp. 309–312.

- ^ Donnison 1961, pp. 227–228.

- ^ Donnison 1961, pp. 213–214.

- ^ Donnison 1961, pp. 231–232.

- ^ Donnison 1961, pp. 329–330.

- ^ a b c Donnison 1961, pp. 428–430.

- ^ Donnison 1961, pp. 408–411.

- ^ Hart 2007, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Buckley 2014, pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b Fraser 1983, pp. 396–397.

- ^ French 2000, pp. 113–115.

- ^ Buckley 2014, pp. 299–300.

References

[edit]- 21st Army Group (November 1945). The Administrative History of the Operations of 21 Army Group on the Continent of Europe 6 June 1944 – 8 May 1945. Germany: 21st Army Group. OCLC 911257199.

- Boileau, D. W. (1954a). Supplies and Transport. The Second World War 1939–1945 Army. Vol. I. London: The War Office. OCLC 16642033.

- Boileau, D. W. (1954b). Supplies and Transport. The Second World War 1939–1945 Army. Vol. II. London: The War Office. OCLC 16642033.

- Buchanan, A. G. B. (1953). Works Services and Engineer Stores. The Second World War 1939–1945 Army. London: The War Office. OCLC 39083450.

- Buckley, John (2014). Monty's Men: The British Army and the Liberation of Europe. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-20534-3. OCLC 882171632.

- Carter, J. A. H.; Kann, D. N. (1961). Maintenance in the Field: 1943–1945. The Second World War 1939–1945 Army. Vol. II. London: The War Office. OCLC 1109671836.

- Donnison, F. S. V. (1961). Civil Affairs and Military Government: North-West Europe 1944–1946. History of the Second World War. London: H.M.S.O. OCLC 268906 – via Archive Foundation.

- Ellis, L. F.; Warhurst, A. E. (1968). Victory in the West. History of the Second World War. Vol. II: The Defeat of Germany. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. OCLC 491514035.

- Essame, H.; Belfield, E. M. G. (1962). The North-West Europe Campaign 1944–1945. Aldershot, Hampshire: Gale & Polden. OCLC 14356493.

- Field, A.E. (1966). "Prisoners of the Germans and Italians". Tobruk and El Alamein. Australia in the War of 1939–1945, Series 1 – Army. Volume III. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. pp. 755–822. OCLC 954993.

- Fraser, David (1983). And We Shall Shock Them: The British Army in the Second World War. London: Cassell & Co. ISBN 978-0-304-35233-3. OCLC 606444563.

- French, David (2000). Raising Churchill's Army: The British Army and the War against Germany 1919–1945. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-924630-4.

- Hart, Stephen Ashley (2007). Colossal Cracks: Montgomery's 21st Army Group in Northwest Europe, 1944–45. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-3383-0. OCLC 942593161.

- Inglis, Drummond (1945). Bridging: Normandy to Berlin. Germany: British Army of the Rhine. OCLC 55542941.

- Krammer, Arnold (July 1992). "Operation PLUTO: A Wartime Partnership for Petroleum". Technology and Culture. 33 (3): 441–466. doi:10.2307/3106633. ISSN 1097-3729. JSTOR 3106633. S2CID 112426992.

- Landon, Charles R., ed. (31 July 1945). Report of Operations (Final After Action Report) 12th Army Group (Report). Vol. VI – G-4 Section. hdl:2027/mdp.39015049794947. OCLC 4520568.

- Lord, Royal B.; Tenney, W. M.; Chase, Earl R.; Lee, Wayne E. (1945). Supply and Maintenance on the European Continent (PDF) (Report). Reports of the ETO General Board. OCLC 23967066. Study No. 130. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- MacDonald, Charles B. (1973). The Last Offensive (PDF). United States Army in World War II – The War Department. Washington, DC: Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army. OCLC 1047769984. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- Micklem, R. (1950). Transportation. The Second World War 1939–1945 Army. London: The War Office. OCLC 5437097.

- Montgomery, Bernard L. (1958). The Memoirs of Field-Marshal the Viscount Montgomery of Alamein. London: Collins. OCLC 1059556308.

- Nicholson, G. W. L. (1956). The Canadians in Italy 1943–1945 (PDF). Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War. Vol. II. Ottawa: Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationery. OCLC 321038327.

- Otway, T. B. H. (1990). Airborne Forces. The Second World War 1939–1945 Army. London: Imperial War Museum. ISBN 0-901627-57-7.

- Pakenham-Walsh, R. P. (1958). History of the Corps of Royal Engineers. Vol. IX, 1938–1948. Chatham: Institution of Royal Engineers. OCLC 1050637341.

- Payton-Smith, Derek Joseph (1971). Oil—A Study of War-time Policy and Administration. History of the Second World War. London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-630074-4. OCLC 185469657.

- Pogue, Forrest (1954). The Supreme Command (PDF). United States Army in World War II – The European Theater of Operations. Washington, DC: Center of Military History, United States Army. LCCN 53-61717. OCLC 1247005.

- Ridgway, Matthew B. (20 May 1945). XVIII Corps (Airborne), Operation the Elbe to the Baltic, 27 April 1945 to 3 May 1945 (PDF) (Report). Combined Arms Research Library. OCLC 1084199521. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- Ruppenthal, Roland G. (1953). Logistical Support of the Armies: Volume I, May 1941 – September 1944 (PDF). Washington, DC: Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army. OCLC 640653201. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- Ruppenthal, Roland G. (1959). Logistical Support of the Armies (PDF). United States Army in World War II – The European Theater of Operations. Vol. II. Washington, DC: Center of Military History, United States Army. OCLC 8743709. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- Stacey, C. P. (1960). The Victory Campaign: The Operations in North-West Europe 1944–1945 (PDF). Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War. Vol. III. Ottawa: The Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationery. OCLC 317352926. Retrieved 25 April 2021.