Bus transport in the United Kingdom

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2024) |

Buses are the most widespread and most commonly used form of public transport in the United Kingdom. In Great Britain, bus transport is owned and governed by private sector companies (subject to government regulation), except in Greater Manchester with the Bee Network and Greater London . If a socially desirable service cannot be economically operated without a subsidy, then local councils can support bus companies to provide the service, often after an open competitive tendering exercise. In Northern Ireland, bus services are publicly owned, governed and delivered, as is the case in the Republic of Ireland.

Passengers board at the front door, and unless fares are automated, they should tell the driver their destination or which ticket is required. Unless there is a separate exit door, alighting passengers should be given space to get off the bus before attempting to enter the bus. Bus passengers typically form a queue at bus stops; which may not always be apparent or obvious. Barging to board a bus, or forcing one's way to the front is not considered acceptable behaviour. Cash is accepted on buses outside Greater London, but urban bus services often do not provide change, and the exact fare should be tendered if possible. Many users are elderly people with bus passes; otherwise, regular users can often purchase a weekly or monthly pass directly from the operator. Some local authorities also offer multi-operator passes. Long distance rural bus services often provide change due to having more fare stages. Contactless fare payment is available on many urban bus services.

Potentially badly-behaved passengers should consult the operator's conditions of carriage for information on unacceptable conduct on board buses; all passengers agree to these terms by using the service. Many bus companies have a lost property office for items forgotten or lost onboard buses; passengers finding lost items should hand them over to the driver, not the police, particularly as many police forces do not return lost property to their owner.[1] A small fee may be charged by the lost property office before releasing lost items to their rightful owner. CCTV is commonplace onboard buses in the UK. Complaints about bus services should be addressed to the bus operator in the first instance, or to the Traffic Commissioner – the regulator of bus services. Complaints about withdrawal of bus services should be addressed to the relevant local authority.

Bus vehicles

[edit]

Historically, full size single and double-decker buses formed the mainstay of the UK bus fleet. Double-decker buses remain common across the country, often running into rural areas. The United Kingdom is unique in the western world as bus companies are generally free to choose whatever vehicle meets their needs from the supplier of their choice, rather than by public sector procurement.

The first dropped-chassis buses were produced in 1924 by Guy Arab Motors.[2] This greatly improved stability by lowering the centre of gravity and also improved loading times by reducing the number of steps to climb aboard the bus.

Outside London, there are now very few cases of rear exit doors (often referred to as "middle doors") on buses to speed up passenger loadings.[citation needed] This is to deter fare-dodging, and to avoid personal injury claims from accidental or deliberate injury by passengers exiting via the rear door while they are closing.[3]

In the 1980s, minibuses were developed from so-called "van-derived" minibus chassis, such as the Ford Transit and the Freight Rover Sherpa. As their popularity increased, designs have become more bus focused, with the numerous Mercedes-Benz models.

Following abortive purpose-built designs such as the Bedford JJL, and the limited use of shortened chassis such as the Seddon Pennine and Dennis Domino, the Dennis Dart introduced the concept of the midibus to the UK operating market in large numbers in the 1990s. Beginning as a short wheelbase bus, some midibus designs have become as long as full size buses.

Developments such as the Optare Solo have further blurred the distinctions between mini and midi buses.

Since the mid-1990s, all bus types must comply with Easy Access regulations, with the most notable change being the introduction of low-floor technology. As of 2022, 99% of the UK's bus fleet are low floor[4] and 95% have onboard CCTV.

Apart from a brief experiment in the 1980s in Sheffield, with the Leyland-DAB, articulated buses (artics; "bendy buses") had not gained a foothold in the UK market. In the new millennium, artics were introduced in various parts of the UK, following a controversial initial introduction in London. However, the London artics had all been withdrawn by 2011.[5]

History

[edit]The horse bus era (1829-1896)

[edit]In 1829 George Shillibeer started the first omnibus service in London, re-using a carriage design he developed in Paris. Over the next few decades, horse bus services developed in London, Manchester and other cities. Double deck omnibuses were introduced in the 1850s, with the upper deck accessed by a ladder, and with "knifeboard seating" where passengers faced outwards with their backs to each other on top of one large combined bench in the centre of the upper deck the "knifeboard".[6] At the Great Exhibition of 1851 which was originally situated in Hyde Park, omnibuses were overwhelmed by demand to the point that a carriage collapsed under the weight of extra passengers.[7] The growth of suburban railways, horse trams (from 1860) and electric trams (from 1885) changed the patterns of horse bus services, but horse buses continued to flourish, particularly where other modes of transport were prohibited by law as was the case with tramways and surface railways in some areas. Carriages improved, with the ladder giving way to an (unsheltered) spiral staircase - which meant women wearing very long skirts could access the upper deck - and seating on the upper deck changing from the knifeboard to "garden-style" seating i.e. forward-facing bench seats. By 1900 there were 3,676 horse buses in London.[8]

Motorisation (1896-1918)

[edit]There were experiments with steam buses in the 1830s,[9] but the Locomotive Act 1861[10] virtually eliminated mechanically propelled road transport from Britain until the law was changed in 1896.[11]

Motor buses were quickly adopted, and soon eclipsed the horse buses. Early operators were the tramway companies, e.g. the British Electric Traction Company, and the railway companies. In London, the horse bus companies, the London General Omnibus Company, and Thomas Tilling introduced motor buses in 1902 and 1904, and the National Steam Car Company started steam bus services in 1909. There was a mixture of fuel types; petrol, diesel and indeed the first electrobus. Before the First World War, petrol-electric buses were favoured by former horse-drivers who struggled with gear-shifts.[12] By the time of the First World War, BET had begun to emerge as a national force.[13]

Interwar regulation and consolidation (1918-1939)

[edit]Bus transport was licensed, with regulations focussing on the weight of vehicles and staff being "fit and proper persons" and minimal route regulations - anyone with a licensed vehicle and staff could enter the market and provide a bus service, with no requirements for a fixed route, route number, or timetable although in practice, this information was provided in some form to attract patronage. Following the Great War, there was a significant increase in the number of diesel motorbuses due to the Armed Forces' preference for diesel vehicles and many drivers and mechanics being demobilised. The first so-called "pirate bus" was the Chocolate Express which began in August 1922.[14] This market disruptor was followed by many other small companies entering the market that it severely depressed revenues for incumbent tramways, railways and bus companies. This culminated in the so-called "pirate bus crisis" of 1924,[15] where Tramway workers led UERL, and the LGOC workers on a London-wide strike over pay.

The London Traffic Act 1924 was rapidly passed after the pirate bus crisis of that year. The Act enabled the Minister of Transport to declare any street in the City of London or Metropolitan Police district a restricted street, preventing any new bus services being introduced in that area. The Act also required all routes to be numbered and registered with the Police Commissioner.[16] The effect of restricted streets, enabled by this Act was protectionism for incumbent bus companies as it gave certainty to investors and creditors that any bought-out competitor would not be immediately replaced by new market entrants and therefore the sector could be consolidated into a local monopoly, competing (duplicate) services could be rationalised to cut costs and on-street competition avoided. Independent bus companies managed to raise a petition with almost a million signatures in 1926 to repeal the Act but this was unsuccessful.[17]

Throughout the 1930s, smaller bus companies were bought up by larger companies, many of which were in turn bought by the Big Four railways. This consolidated the transport sector into a private sector oligopoly before the Second World War. In London, the UERL which included the dominant bus operator became the London Passenger Transport Board in 1933 an early quango running the majority of public transport in London except for railways run by the Big Four, which included most railways south of the Thames. The Board did not receive government subsidy except under the New Works Programme and decision-making did not involve the London County Council.

Nationalisation and decline (1947-1968)

[edit]

The post-war Labour government embarked on a programme of nationalisation of transport. Under the Transport Act 1947, the British Transport Commission acquired the bus services of Thomas Tilling, Scottish Motor Traction and the large independent Red & White. By the nationalisation of the railways, the BTC also acquired interests in many of BET's bus companies, but BET was not forced to sell its companies and they were not nationalised.

In 1962 the BTC's bus companies were transferred to the Transport Holding Company. Then in 1968 BET sold its UK bus companies to the Transport Holding Company. Almost all of the UK bus industry was by then owned by the government under the National Bus Company or by local governments.

Bus passenger numbers continued to decline in the 1960s. The Transport Act 1968 was an attempt to rationalise publicly owned bus services and provide a framework for the subsidy of uneconomic but socially necessary services. The Act:

- transferred the English and Welsh bus companies of the Transport Holding Company to the new National Bus Company

- transferred the country services of London Transport to the NBC.

- transferred the Scottish bus companies of the THC to the Scottish Transport Group

- transferred municipal bus operations in the 5 large metropolitan areas outside London to new Passenger Transport Executives, together with some operations of THC companies in those areas.

- granted powers to local governments to provide subsidies to cover NBC subsidiaries' operating defecits incurred when delivering the regulated networks.

- introduced the New Bus Grant which promoted driver-only buses.

The National Bus Company underwent a corporate restructure in 1972, consolidating the former companies into a more uniform design and brand, with intercity services coming under one brand - National Travel - which would eventually evolve into National Express.

Phasing out of crewed (conductor) buses (1968-1980)

[edit]

Deregulation and Privatisation (1981-1990)

[edit]Consolidation (1990-2004)

[edit]

Many municipal and former NBC companies struggled to adjust to on-road competition and were sold to their management, employees, or other operators, which were in turn bought by one of the now-dominant bus operator groups - sometimes referred to as 'private', or 'group' operators. PTEs were also required to split and sell their bus departments. The largest of the group operators - FirstGroup began as the Aberdeen municipal transport department - then renamed as Grampian Regional Transport - which was willingly sold by their local authority and grew by acquisition.

After an initial burst of new entrants into the bus market, causing bus wars many of these new companies went bust, were acquired by other operators, or otherwise exited the market and new market entrants slowed. Companies began merging and growing in the 1980s and 1990s, some growing in the pursuit of listing on the stock exchange. Five major bus groups emerged - two (FirstGroup and Go-Ahead Group) were formed from NBC bus companies sold to their management, two (Stagecoach and Arriva) were independent companies which pursued aggressive acquisition policies, and National Express was the privatised coach operator which diversified into bus operation.

Recent trends have seen the disposal of relatively large companies where revenues do not meet shareholder expectations. The Stagecoach Group went so far as to dispose of its two large London operations, citing the inability to grow the business within the London regulated structure.[19] They later repurchased their London operations in 2010, after it entered administration.[20]

Some large overseas groups have also entered the UK bus market, such as Transit Systems, who purchased First's London operations, under the Tower Transit name,[21] and ComfortDelGro, who own Metroline, and recently purchased New Adventure Travel

Disability access (2005)

[edit]Almost all buses were not accessible to wheelchair users until the Disability Discrimination Act 2005 forced bus companies to acquire low-floor accessible buses. This followed an extensive campaign of direct action by disabled people's groups - often blocking or chaining themselves to inaccessible buses.[22] Low-floor accessible buses were gradually phased in with a negligible number of non-accessible vehicles running in 2017-18.[23]

Concessionary travel expansion (2006-)

[edit]In 2006, the Scottish Executive introduced the first national concessionary bus travel scheme for all persons aged 60 or over, replacing various local concessionary travel schemes. In England, a similar scheme was introduced at the national level, but has since raised the eligibility age to state pension age. Neither of these concessionary travel schemes made a noticeable impact on bus patronage. The Scottish Government introduced another concessionary travel scheme for people aged 11–21 in 2022.[24] The young persons' scheme has appears to have been more successful at increasing patronage than the previous schemes.

Coronavirus pandemic, lockdown and recovery (2020-2024)

[edit]Bus patronage decreased sharply following the lockdown in response to the covid pandemic. The UK government established the Covid Bus Service Support Grant (CBSSG) which was paid to local governments outside Greater London to maintain bus services through the pandemic.[25] Greater London had a separate programme of support for its services, with frequent disputes between the UK government and Sadiq Khan, the Mayor of London at the time.

Scotland provided funding direct to bus operators through its equivalent scheme, Covid Support Grant.[26] The Welsh Government supported its bus services through its Bus Emergency Scheme[27]

Between January 2022 and January 2023, registered bus routes fell by 9.5%.[28]

As was the case in many other countries, many bus drivers contracted coronavirus with higher death rates than the general population.[29]

Following lifting of restrictions, many bus services struggled to restore previous levels of service due to the loss of bus drivers to the haulage sector who offer better pay, retirement, ill-health, or premature death. Travel patterns have been altered, with the decline in city-centre working in many areas,[30] which significantly impacts on bus companies' income. Governments have intervened to support bus services in a variety of ways, including a £2 cap on single fares in England which was launched on 1 January 2023.[31]

Decarbonisation

[edit]The UK Government and devolved administrations have worked to transition buses away from diesel to hydrogen fuel cell or battery-electric powertrains. The Zero Emission Bus Regional Area scheme provided funding to local governments in England to work with bus companies to deliver zero emission buses and supporting infrastructure in their area.[32] The Scottish Ultra Low Emission Bus Schemes provided funding to bus companies directly to acquire battery electric buses and supporting infrastructure.[33] London [34] and Northern Ireland[35] have acquired zero emission buses directly due to these markets being regulated in their respective areas.

Hydrogen

[edit]Hydrogen buses were introduced as a trial in 2015 in Aberdeen,[36] and ran until 2020.[37] The following year, the world's first hydrogen powered double-deckers began service in the city.[37] Later in 2021, Transport for London introduced 20 hydrogen double-deckers.[38][39]

Regulation

[edit]

Today, bus service provision for public transport in the UK is regulated in a variety of ways. Bus transport in London is regulated by Transport for London.[40] Bus transport in some large conurbations is regulated by Passenger Transport Executives.[41] Bus transport elsewhere in the country must meet the requirements of the local Traffic Commissioner, and run to their registered service. Under the free market, the barriers to entry into public bus service operation is aimed to be as low as possible.

Operators of service buses and coaches (PSVs) must hold an operating licence (an 'O' licence). Under an O licence, operators are registered with the Office of the Traffic Commissioner under a company name, and if applicable, any trading names, and are allocated a maximum fleet size allowed to be stored at nominated operating centres. An O licence is required for each of the 8 national Traffic Areas in which an operator has an operating centre. Reducing the vehicle allocation on, or revoking, an O licence can occur if an operator is found to be operating in contravention of any laws or regulations.[42]

In Northern Ireland, coach, bus (and rail) services remain state-owned and are provided by Translink.[43]

Using the example of bus passenger growth seen in London under the changes made by Transport for London, several parties have advocated a return to increased regulation of bus services along the London model.

The Transport Act 2000 made certain provisions for increased cooperation between local authorities and bus operators to take measures to improve services, such cooperation was previously barred under competition law. Under the act, Quality Bus Partnerships were enabled, although this had limited success. In Sheffield the first Statutory Quality Partnership was introduced along the Barnsley Road corridor, shortly followed in Barnsley with a Partnership introduced covering the A61 (north) and the new Barnsley Interchange. In Cardiff, the Statutory Quality Bus Partnership has also been used, with the introduction of new buses on Cardiff Bus routes. The Act also included measures allowing the registration of variable route services, as demand responsive transport.

In 2004, regulations were amended to further allow fully flexible demand responsive transport bus services.[44]

Bus industry composition

[edit]Almost all bus operating companies are owned in the private sector. Some are operated as community-based or not for profit entities, or as local authority arms length companies, as municipal bus companies. There are thousands of independent bus companies; some are still family-owned. These companies often deliver contract work such as private hire, or deliver council-supported bus services.

The largest bus operator groups in Great Britain are:

There are nine municipal bus operators in the UK:

- Lothian Buses

- Cardiff Bus

- Newport Bus

- Reading Buses

- Nottingham City Transport[45]

- Warrington's Own Buses

- Ipswich Buses

- Blackpool Transport

- Translink

Of the major bus groups, only Stagecoach began as a bus operator which had not previously been in the public sector, although it later acquired many former public sector companies. Arriva was acquired by Deutsche Bahn in 2010.

The majority of bus services in both urban and rural areas are now run by subsidiaries of a few major bus groups, some of which also hold the franchises to many train operating companies and light rail systems.

Subsidies

[edit]

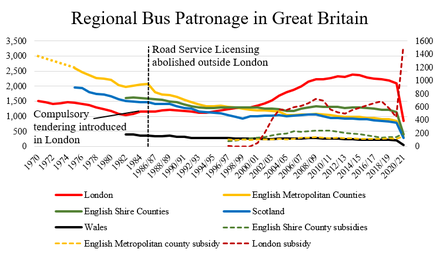

It is disputed whether bus transport is intensively subsidised or not; concessionary travel reimbursement accounts for around 45 per cent of operator revenue,[46] especially in London. However, this is reimbursement for fare revenue foregone from charging these passengers fares. It is periodically negotiated locally in England, with the operator receiving a fraction of the adult single fare. This fraction often depends on local authority budget constraints. BSOG and local authority supported services (awarded after competitive open tendering) account for a far smaller fraction of operators' income.[47]

In 2014/15[needs update], there were 5.20 billion bus journeys in the UK, 2.4 billion of which were in London.[18] The UK bus network has shrunk by 8% over the past decade due to government subsidy cuts and a reduction in commercial operations in the north of England.[48][49][50]

The Concessionary Travel Schemes in Great Britain are schemes which reimburse bus operators for revenue foregone in exchange for providing free passage to the cardholder on their services. Operator reimbursement is calculated according to a set percentage of the single fare for the journey, the percentage of the single fare varies by transport authority.[51] The schemes are designed so that operators be no better or worse off than if the scheme had not existed.[52] It is therefore debatable whether this counts as a subsidy to the operator, or even as an incentive to operators to grow patronage, when it is the passenger who benefits from no longer paying bus fares.

For 2014/15[needs update], subsidies (including the cost of concessionary fares) in England were £2.3 billion, made up of £826 million for London, £516 million for metropolitan areas outside London and £951 million for non-metropolitan areas.[18] In Scotland, they were £291 million for 2013/14.[53]

Vehicle preservation

[edit]Interest in preservation of historical buses is maintained in the UK by various museums and heritage/preservation groups, ranging from attempts to restore a single bus, to whole collections. While many preserved buses are vintage, increasingly, 'modern' types, such as the Leyland National, and the Optare Spectra[54] are being preserved. With the fleet replacement of the major groups, it is not uncommon for many preserved buses to still have contemporary models still in service.

Manufacturers

[edit]Early UK bus manufacturers included private companies such as Guy Motors, Leyland Motors and AEC. Some bus operating companies, such as the London General Omnibus Company and Midland Red, also manufactured buses.

Current British bus manufacturers include Alexander Dennis, Plaxton, Switch (Formerly Optare) and Wrightbus.

During nationalisation, two UK manufacturers fell under government ownership, Bristol Commercial Vehicles and Eastern Coach Works. Later, Leyland Bus was also effectively nationalised.

Before, and increasingly after privatisation, foreign manufacturers such as Scania entered the UK market, followed by the likes of Mercedes-Benz.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ https://beta.northumbria.police.uk/our-services/report-it/lost-found-and-seized-property/

- ^ "Guy Motors".

- ^ "Bus chiefs slam the door on fraudsters and fare dodgers | The Scotsman".

- ^ "Annual bus statistics: Year ending March 2022 (Revised)". Gov.uk.

- ^ "Bendy bus makes final journey for Transport for London". BBC News. 10 December 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ "History of the Bus". YouTube.

- ^ "Omnibus 150". YouTube.

- ^ "The Horse Bus 1662-1932 by Peter Gould". Archived from the original on 14 July 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

- ^ See Walter Hancock and Sir Goldsworthy Gurney

- ^ https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Vict/24-25/70/enacted

- ^ "The Steam Bus 1833-1923 by Peter Gould". Archived from the original on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

- ^ "Ian's BUS STOP: The TILLING LONDON PETROL ELECTRIC TTA1".

- ^ "Early Motorbuses and Bus Services 1896-1986 - Local Transport History". Archived from the original on 8 May 2008.

- ^ David Berguer, Under the Wires at Tally Ho: Trams and Trolleybuses of North London, 1905-1962 (History Press, 2011)

- ^ https://repository.essex.ac.uk/30938/1/Openaccess-Hybrid_out_of_Crisis.pdf

- ^ "Ian's BUS STOP: The LONDON TRANSPORT Dennis 4-ton".

- ^ https://www.ltmuseum.co.uk/collections/stories/transport/london-buses-between-wars

- ^ a b c d "Government bus statistics". Gov.uk. 26 April 2023.

- ^ Stewart, Steven (2006). "London bus sold off in £264m deal" (PDF). On Stage. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 February 2019. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- ^ Fletcher, Nick (15 October 2010). "Stagecoach buys back London bus business at a discount". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 February 2019. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- ^ Australian public transport innovator acquires first international fleet Archived 9 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine Transit Systems

- ^ "When disabled people took to the streets to change the law". BBC News. 7 November 2015.

- ^ https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1141449/bus06.ods

- ^ "Free bus travel for under-22s in Scotland begins". BBC News. 31 January 2022.

- ^ "Supporting vital bus services: Recovery funding". Gov.uk. 6 July 2021.

- ^ "COVID-19 Support Grant | Transport Scotland".

- ^ "Emergency Covid funding for Wales' buses to be withdrawn". BBC News. 2 April 2023.

- ^ Goodier, Michael; Otte, Jedidajah (24 January 2023). "Almost one in 10 local bus services axed over last year in Great Britain". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ "COVID-19 deaths by job sector - Office for National Statistics".

- ^ "Bus funding update". 20 February 2023.

- ^ "£2 bus fare cap". Gov.uk. 17 May 2023.

- ^ "[Withdrawn] Zero Emission Bus Regional Areas (ZEBRA) scheme". 2 March 2023.

- ^ "Scottish Ultra-Low Emission Bus Scheme | Transport Scotland".

- ^ "Bus fleet data & audits".

- ^ "New Zero Emission Fleet".

- ^ "HyTransit". Fuel Cell Electric Buses. 13 February 2018. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ a b Gossip, Alastair (27 January 2021). "World-first hydrogen double deckers launched on passenger services in Aberdeen". Evening Express. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ "London launches England's first hydrogen-powered double decker buses". CityAM. 23 June 2021. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- ^ Jackson, Peter (18 May 2021). "TfL launches first hydrogen-powered buses in the capital". CBW. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- ^ "London Service Permits". TfL. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- ^ "Passenger Transport Executives | Office of Rail and Road". orr.gov.uk. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- ^ "Public Service Vehicle Operator Licensing : Guide for Operators" (PDF). VOSA. November 2011. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- ^ "The Northern Ireland Transport Holding Company". Department for Infrastructure. 23 June 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- ^ Enoch, Marcus; Ison, Stephen; Laws, Rebecca; Zhang, Lian. "Evaluation Study of Demand Responsive Transport Services in Wiltshire" (PDF). Transport Studies Group, Loughborough University. p. 13. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- ^ https://www.nctx.co.uk/plan-your-journey

- ^ Butcher, Louise (4 December 2013). Buses: grants and subsidies. House of Commons Library.

- ^ "Transport for London's budget deficit down but uncertainty looms". BBC News. 20 March 2019.

- ^ "Britain's bus coverage hits 28-year low". BBC News. 16 February 2016.

- ^ "Bus Usage - Gov.uk". assets.publishing.service.gov.uk.

- ^ "Bus Patronage - UK Government". assets.publishing.service.gov.uk. 26 April 2023.

- ^ Concessionary travel for older and disabled people: guidance on reimbursing bus operators (England)

- ^ "Concessionary Travel Scheme" (PDF). governance.southyorkshire-ca.gov.uk.

- ^ "Bus and coach travel statistics". www.transportscotland.gov.uk.

- ^ "West Midlands Optare Spectra R1 NEG". Transport Museum Wythall. Retrieved 5 December 2018.