Green Book (film)

| Green Book | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Peter Farrelly |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Sean Porter |

| Edited by | Patrick J. Don Vito |

| Music by | Kris Bowers |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures[1] |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 130 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $23 million[3] |

| Box office | $321.8 million[4] |

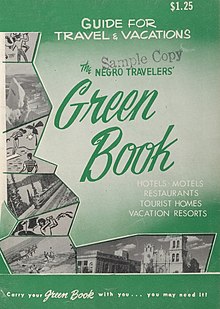

Green Book is a 2018 American biographical comedy-drama film directed by Peter Farrelly. Starring Viggo Mortensen and Mahershala Ali, the film is inspired by the true story of a 1962 tour of the Deep South by African American pianist Don Shirley and Italian American bouncer and later actor Frank "Tony Lip" Vallelonga, who served as Shirley's driver and bodyguard. Written by Farrelly alongside Lip's son Nick Vallelonga and Brian Hayes Currie, the film is based on interviews with Lip and Shirley, as well as letters Lip wrote to his wife.[5] It is named after The Negro Motorist Green Book, a guide book for African American travelers founded by Victor Hugo Green in 1936 and published until 1966.

Green Book had its world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival on September 11, 2018, where it won the People's Choice Award. It was then theatrically released in the United States on November 16, 2018, by Universal Pictures, and grossed $321 million worldwide. The film received positive reviews from critics, with praise for the performances of Mortensen and Ali, although it also drew some criticism for its depiction of both race and Shirley.

Green Book received many awards and nominations. It won the Academy Award for Best Picture, Best Original Screenplay, and Best Supporting Actor (for Ali). It also won the Producers Guild of America Award for Best Theatrical Motion Picture, the Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy, and the National Board of Review award for the best film of 2018, and was chosen as one of the top 10 films of the year by the American Film Institute. Ali also won the Golden Globe, Screen Actors Guild, and BAFTA Awards for Best Supporting Actor.[6][7]

Plot

[edit]In the Bronx in 1962, Italian American bouncer Tony Lip searches for new employment while the Copacabana is closed for renovations. He is invited to an interview with Dr. Don Shirley, an African American pianist in need of a driver for his eight-week concert tour through the Midwest and Deep South.

Don hires Tony on the strength of his references. They embark with plans to return to New York City on Christmas Eve. Don's record label gives Tony a copy of The Negro Motorist Green Book, a guide for African American travelers that contains the addresses of those motels, restaurants, and filling stations that would serve them in the Jim Crow South.[8]

Tony and Don initially clash as Tony feels uncomfortable being asked to act with more refinement, while haughty Don is displeased by Tony's habits. As the tour progresses, Tony is impressed with Don's talent on the piano and is increasingly appalled by the discriminatory treatment that Don receives from his hosts and the general public when he is not on stage.

In Louisville, Kentucky, a group of white men beat Don and threaten his life in a bar before Tony rescues him. He instructs Don not to go out without him for the rest of the tour.

Throughout the journey, Don helps Tony write eloquent letters to his wife, which deeply move her. Tony encourages Don to get in touch with his own estranged brother, but Don is hesitant, observing that he has become isolated by his professional life and achievements. Don is later found in a homosexual encounter with a white man at a pool, and Tony bribes officers to prevent his arrest.

In Mississippi, the two are arrested after police officers pull them over late at night in a sundown town, and Tony punches one officer after being insulted. While in jail, Don asks to phone his lawyer and instead uses the call to reach Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, who pressures the governor and police officers to release the two.

Once they are free and back on the road, Don reprimands Tony for his distasteful actions, and a heated argument erupts regarding race relations and meritocracy, during which Don expresses frustration at feeling rejected by the black community due to his mannerisms while the white community either mistreats him or uses him to make themselves look open-minded. They eventually find a hotel for the night and manage to reconcile.

On the night of Don's final performance in Birmingham, Alabama, he is refused entry into the whites-only dining room of the country club where he has been hired to perform. Tony threatens the manager, and Don refuses to play since they refuse to serve him in the room with his audience. Tony and Don leave the venue and instead have dinner at a black blues club, where Don joins the band on piano.

The pair head north in an attempt to make it home by Christmas Eve but are caught in a blizzard. They are then once again pulled over by a police officer. Worried they are about to get the same treatment, both are surprised when the officer turns out to be friendly and only pulled them over because he noticed one of their tires was flat. The officer then helps them fix the tire and they are able to make it home.

Tony invites Don to have dinner with his family, but Don declines. Sitting alone at home, he changes his mind and returns to Tony's, where he receives a surprisingly warm welcome by Tony's extended family.

The end title cards show real-life photos of Don and Tony. It states that Don continued to tour and create music, while Tony went back to his work at the Copacabana, and that they remained friends until dying months apart in 2013.

Cast

[edit]- Mahershala Ali as Dr. Don Shirley

- Viggo Mortensen as Tony Lip

- Linda Cardellini as Dolores Venere, Tony's wife

- Sebastian Maniscalco as Johnny Venere, Dolores' brother

- Dimiter D. Marinov as Oleg Malacovich, Dr. Shirley's cellist

- Mike Hatton as George Dyer, Dr. Shirley's bassist

- Von Lewis as Bobby Rydell, Copa Singer

- Brian Stepanek as Graham Kindell, country club manager

- Joseph Cortese as Gio Loscudo

- Iqbal Theba as Amit, Don's servant

- P. J. Byrne as Record Exec

- Tom Virtue as Morgan Anderson

- Don Stark as Jules Podell

In addition, Tony and Dolores Vallelonga's son, Frank Jr., appears as his own uncle, Rudy (Rodolfo) Vallelonga (who says, "I'm just saying, we're an arty family"), while their younger son (and the film's co-producer and co-screenwriter), Nick, appears as Augie, the Mafioso who offers Tony a job doing "things" while the Copacabana is under renovation. The real Rodolfo Vallelonga appears as his own father, Grandpa Nicola Vallelonga, while the real Louis Venere appears as his own father, Grandpa Anthony Venere. Another co-producer and co-screenwriter, Brian Currie, plays the Maryland State Trooper who helps out in the snow storm. Actor Daniel Greene, who frequently appears in films directed by the Farrelly brothers, portrays Macon Cop #1.

Production

[edit]Viggo Mortensen began negotiations to star in the film in May 2017 and was required to gain 40–50 pounds (18–23 kg) for the role.[3] Peter Farrelly was set to direct from a screenplay written by Nick Vallelonga (Tony Lip's son), Brian Currie, and himself.[9]

On November 30, 2017, the lead cast was set with Mortensen, Mahershala Ali, Linda Cardellini and Iqbal Theba confirmed to star. Production began that week in New Orleans.[10][11][12] Sebastian Maniscalco was announced as part of the cast in January 2018.[13] Score composer Kris Bowers also taught Ali basic piano skills and was the stand-in when closeups of hands playing were required.[14]

The film is executive produced by Jeff Skoll, Jonathan King, Octavia Spencer, Kwame L. Parker, John Sloss and Steven Farneth.[15]

Writing

[edit]

The script was written by Vallelonga's son Nick Vallelonga, as well as Brian Hayes Currie and Peter Farrelly, after conversations with his father and Shirley.[16]

Music

[edit]For the film's soundtrack, Farrelly incorporated an original score by composer Kris Bowers and one of Shirley's own recordings. The soundtrack also includes rarities from 1950s and 1960s American music recommended to him by singer Robert Plant, who was dating a friend of Farrelly's wife at the time he had finished the film's script. During dinner on a double date, his wife and her friend stepped outside to smoke and the director asked Plant for advice on picking songs for the film that would be relatively unknown to contemporary audiences. This prompted Plant to play Farrelly songs via YouTube, including Sonny Boy Williamson II's "Pretty 'Lil Thing" and Robert Mosley's "Goodbye, My Lover, Goodbye".[17]

In an interview with Forbes, the director explained that the soundtrack ended up not only avoiding rote nostalgia, "but also those songs were really inexpensive and I did not have a huge budget so I was able to come up with some sensational pop songs from the time that were long forgotten."[18] The music played at the black blues club toward the end of the film featured the piano performance of Étude Op. 25, No. 11 (Chopin), known as the Winter Wind etude by Chopin, was not included in the soundtrack release.

A soundtrack album was released digitally on November 16, 2018 and physically on November 30, 2018,[19] by Milan Records,[20] featuring Bowers' score, songs from the plot's era, and a piano recording by Shirley.[21] According to the label, it was streamed approximately 10,000 times per day during January 2019. This rate doubled the next month as the album surpassed one million streams worldwide and became the highest-streamed jazz soundtrack in Milan's history.[20]

Release

[edit]Originally in production at Focus Features, the company ultimately passed on the project. Participant Media then financed the $23 million budget for Green Book, but Farrelly was concerned about the fact that Participant had a distribution deal with Focus. Knowing very well about Steven Spielberg and his studio's longtime relationship with Universal Pictures, Farrelly decided to call his agent Richard Lovett, who also represents Spielberg. Lovett managed to convince Spielberg to watch the film, which he loved so much that he reportedly watched it five times over two weeks, calling it "his favorite buddy movie since Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid". Spielberg then took the film to DreamWorks Pictures, which currently has a domestic distribution deal with Universal.[22]

Green Book began a limited release in 20 cities, in the United States, on November 16, 2018, and expanded nationwide on November 21, 2018. The film was previously scheduled to begin its release on the 21st.[23] The studio spent an estimated $37.5 million on prints and advertisements for the film.[24]

The film had its world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival on September 11, 2018.[25] It also opened the 29th New Orleans Film Festival on October 17, 2018, screened at AFI Fest on November 9, 2018[26] and was programmed as the surprise film at the BFI London Film Festival.[27]

On November 7, 2018, during a promotional panel discussion, Mortensen said the word "nigger". He prefaced the sentence with, "I don't like saying this word", and went on to compare dialogue "that's no longer common in conversation" to the period in which the film is set. Mortensen apologized the next day, saying that "my intention was to speak strongly against racism" and that he was "very sorry that I did use the full word last night, and will not utter it again".[28]

Home media

[edit]Green Book was released on DVD and Blu-ray on March 12, 2019, by Universal Pictures Home Entertainment. The film was made available for purchase on streaming video in digital HD from Amazon Video and iTunes on February 19, 2019.[29] It was also released on DVD and Blu-Ray by Entertainment One through 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment in the UK in 2018.

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]Green Book grossed $85.1 million in the United States and Canada, and $236.7 million in other territories, for a total worldwide gross of $321.8 million, against a production budget of $23 million.[4] Deadline Hollywood calculated the net profit of the film to be $106 million, when factoring together all expenses and revenues.[24]

The film made $312,000 from 25 theaters in its opening weekend, an average of $12,480 per venue, which Deadline Hollywood called "not good at all", although TheWrap said it was a "successful start," and noted strong word-of-mouth would likely help it going into its wide release.[30][31] The film had its wide expansion alongside the openings of Ralph Breaks the Internet, Robin Hood and Creed II, and was projected to gross around $7–9 million over the five-day weekend, November 21 to 25.[32] It made $908,000 on its first day of wide release and $1 million on its second. It grossed $5.4 million over the three-day weekend (and $7.4 million over the five), finishing ninth. Deadline wrote that the opening was "far from where [it needed] to be to be considered a success," and that strong audience word of mouth and impending award nominations would be needed in order to help the film develop box office legs. Rival studios argued that Universal went too wide too fast: from 25 theaters to 1,063 in less than a week.[33]

In its second weekend the film made $3.9 million, falling just 29% and leading some industry insiders to think it would achieve $50 million during awards season.[34] In its third weekend of wide release, following its Golden Globe nominations, it dropped 0% and again made $3.9 million, then made $2.8 million the following weekend.[35][36] In its eighth weekend, the film made $1.8 million (continuing to hold well, dropping just 3% from the previous week).[37] It then made $2.1 million in its ninth weekend (up 18%) and $2.1 million in its 10th.[38] In the film's 11th week of release, following the announcement of its five Oscar nominations, it was added to 1,518 theaters (for a total of 2,430) and made $5.4 million, an increase of 150% from the previous weekend and finishing sixth at the box office.[39] The weekend following its Best Picture win, the film was added to 1,388 theaters (for a total of 2,641) and made $4.7 million, finishing fifth at the box office. It marked a 121% increase from the previous week, as well as one of the best post-Best Picture win bumps ever,[40] and largest since The King's Speech in 2011.[41]

Green Book was a surprise success overseas, especially in China where it debuted to a much higher-than-expected $17.3 million, immediately becoming the second highest-grossing Best Picture winner in the country behind Titanic (1997).[42] As of March 7, 2019, the largest international markets for the film were China ($26.7 million), France ($10.7 million), the United Kingdom ($10 million), Australia ($7.8 million) and Italy ($8.6 million).[43] By March 13, China's total had grown to $44.5 million.[44] On March 31 the film passed $300 million at the global box office, including $219 million from overseas territories. Its largest markets to-date were China ($70.7 million), Japan ($14.6 million), France ($14 million) Germany ($13.5 million) and the UK ($12.9 million).[45]

Critical response

[edit]

On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, Green Book holds an approval rating of 77% based on 363 reviews, with an average rating of 7.2/10. The website's critical consensus reads: "Green Book takes audiences on an excessively smooth ride through bumpy subject matter, although Mahershala Ali and Viggo Mortensen's performances add necessary depth."[46] On Metacritic the film has a weighted average score of 69 out of 100, based on 52 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[47] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film a rare average grade of "A+" on an A+ to F scale, while PostTrak reported filmgoers gave it a 91% positive score, with 80% saying they would definitely recommend it.[33][48]

Writing for The San Francisco Chronicle, Mick LaSalle praised Ali and Mortensen and said: "...there's something so deeply right about this movie, so true to the time depicted and so welcome in this moment; so light in its touch, so properly respectful of its characters, and so big in its spirit, that the movie acquires a glow. It achieves that glow slowly, but by the middle and certainly by the end, it's there, the sense of something magical happening, on screen and within the audience."[49] Steve Pond of TheWrap wrote, "The movie gets darker as the journey goes further South, and as the myriad indignities and humiliations mount. But our investment in the characters rarely flags, thanks to Mortensen and Ali and a director who is interested in cleanly and efficiently delivering a story worth hearing."[50]

Jazz artist Quincy Jones said to a crowd after a screening: "I had the pleasure of being acquainted with Don Shirley while I was working as an arranger in New York in the '50s, and he was without question one of America's greatest pianists ... as skilled a musician as Leonard Bernstein or Van Cliburn ... So it is wonderful that his story is finally being told and celebrated. Mahershala, you did an absolutely fantastic job playing him, and I think yours and Viggo's performances will go down as one of the great friendships captured on film."[51]

Some critics thought Green Book perpetuated racial stereotyping by advancing the white savior narrative in film. Salon said the film combines "the white savior trope with the story of a bigot's redemption."[52][53] Peter Farrelly told Entertainment Weekly that he was aware of the white savior trope before filming and sought to avoid it. He said he had long discussions with the actors and producers on the point, and believes that it was not advanced by the film, saying it is "about two guys who were complete opposites and found a common ground, and it's not one guy saving the other. It's both saving each other and pulling each other into some place where they could bond and form a lifetime friendship."[53]

New York Times writer Wesley Morris characterized the film as being a "racial reconciliation fantasy". Morris argues that the film represents a specific style of racial storytelling "in which the wheels of interracial friendship are greased by employment, in which prolonged exposure to the black half of the duo enhances the humanity of his white, frequently racist counterpart".[54] Writing a positive appreciation in The Hollywood Reporter, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar noted that "filmmakers are history’s interpreters, not its chroniclers."[55]

Criticism from Shirley's relatives

[edit]Though the film was generally praised, Shirley's relatives criticized it because they thought it misrepresented the pianist's relationship with his family and they were not contacted by studio representatives until after development started. Shirley's brother, Maurice Shirley, said, "My brother never considered Tony to be his 'friend'; he was an employee, his chauffeur (who resented wearing a uniform and cap). This is why context and nuance are so important. The fact that a successful, well-to-do black artist would employ domestics that did NOT look like him, should not be lost in translation."[56] But according to audio recordings from the 2010 documentary "Lost Bohemia", Shirley said that "I trusted him implicitly. You see, Tony got to be, not only was he my driver. We never had an employer/employee relationship." The interviews also supported other events depicted in the film.[57]

Writer-director Peter Farrelly said that he was under the impression that there "weren't a lot of family members" still alive, that they did not take major liberties with the story, and that relatives of whom he was aware had been invited to a private screening for friends and family.[58] Tony Vallelonga's son, Nick – and the film's co-writer – acknowledged that he was sorry that he had offended members of the Shirley family because he did not speak to them. He told Variety that "Don Shirley himself told me not to speak to anyone" and that Shirley "approved what I put in and didn't put in."[16] According to Shirley's nephew Edwin Shirley III, actor Mahershala Ali called him to apologize, saying that "I did the best I could with the material I had" and that he was not aware that there were "close relatives with whom I could have consulted to add some nuance to the character."[58]

Shirley's cellist Jüri Täht was surprised to see a stage of his life depicted in a movie, and that he had been replaced by a fictionalised version of himself (the character of Oleg). He was dismayed by the fact that Oleg was Russian in the film while he was an Estonian whose family had had to flee the USSR.[59]

Awards and nominations

[edit]Green Book has received numerous award nominations. In addition to winning the People's Choice Award at the Toronto International Film Festival in September 2018,[60] Green Book was nominated for five awards at the 91st Academy Awards, winning three awards for Best Picture, Best Original Screenplay and Best Supporting Actor for Mahershala Ali. Green Book was the fifth film to win Best Picture without a Best Director nomination. Green Book had five nominations at the 76th Golden Globe Awards, with the film winning Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy. The National Board of Review awarded it Best Film, and it was also recognized as one of the Top 10 films of the year by the American Film Institute.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Debruge, Peter (September 11, 2018). "Film Review: 'Green Book'". Variety. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- ^ He, Laura (February 25, 2019). "Alibaba Pictures shares rise after striking gold with Green Book's best picture win at the Oscars". South China Morning Post. Retrieved February 26, 2019.

- ^ a b Siegel, Tatiana (November 13, 2018). "Making of 'Green Book': A Farrelly Brother Drops the Grossout Jokes for a Dramatic Road Trip in the 1960s Deep South". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- ^ a b "Green Book (2018)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- ^ Diamond, Anna (December 2018). "The True Story of the 'Green Book' Movie". Smithsonian.com. Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- ^ "Mahershala Ali wins Best Supporting Actor Golden Globe for 'Green Book'". EW.com. January 6, 2019. Retrieved January 17, 2019.

- ^ "Mahershala Ali Wins First Golden Globe for 'Green Book'". The Hollywood Reporter. January 6, 2019. Retrieved January 17, 2019.

- ^ "The Green Book". NYPL Digital Library. January 20, 2019. Retrieved January 20, 2019.

- ^ Kroll, Justin (May 31, 2017). "Viggo Mortensen Circling Peter Farrelly's Next Film 'Green Book' (EXCLUSIVE)". Variety. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ Sneider, Jeff (November 30, 2017). "Viggo Mortensen, Mahershala Ali To Star In Peter Farrelly's ROAD Trip Drama "Green Book"". Tracking Board. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ Scott, Mike (October 31, 2017). "Movie inspired by 'The Negro Motorist Green Book' to film in New Orleans". Nola. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ N'Duka, Amanda (November 30, 2017). "Iqbal Theba Joins 'Green Book'; Michael Beach Cast In 'Foster Boy'; Peter Strauss Boards 'Operation Finale'". Deadline. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ Galuppo, Mia (January 16, 2018). "Comedian Sebastian Maniscalco Joins Viggo Mortensen in Drama 'Green Book' (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ O'Connell, Sean J. (February 2019). "Bowers Explores Shirley's Work for 'Green Book' Film". DownBeat. Vol. 86, no. 2. p. 23.

- ^ "Green Book". Universal Pictures. Retrieved October 5, 2024.

- ^ a b "Green Book' Writer Defends Film After Family Backlash: Don Shirley 'Approved What I Put In". Variety. January 9, 2019. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- ^ Baltin, Steve (February 16, 2019). "Robert Plant's Friendly Role In 'Green Book' Soundtrack And Other Behind The Scenes Secrets". Forbes Magazine. Retrieved November 10, 2021.

- ^ Lifton, Dave (February 18, 2019). "How Robert Plant Helped Curate the 'Green Book' Soundtrack". Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- ^ "Green Book – Kris Bowers". AllMusic. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- ^ a b Reitman, Shelby (February 13, 2019). "'Green Book' Official Soundtrack Passes 1 Million Global Streams". Billboard. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- ^ Bundel, Ani (December 2018). "The 'Green Book' Soundtrack Will Fill You With So Much Joy". Elite Daily. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (February 14, 2019). "How Steven Spielberg Changed The Course For 'Green Book' – Awardsline Screening Series". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (October 31, 2018). "'Green Book' Going Earlier In Limited Release Off Awards Season Heat". Deadline Hollywood. Penske Business Media. Retrieved October 31, 2018.

- ^ a b D'Alessandro, Anthony (April 8, 2019). "Small Movies, Big Profits: 2018 Most Valuable Blockbuster Tournament". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- ^ Kay, Jeremy (August 14, 2018). "Toronto unveils Contemporary World Cinema, more Galas and Special Presentations". Screen International. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ Hammond, Pete (October 11, 2018). "AFI Fest Adds Gala Screenings 'Green Book', 'Widows', World Premiere Of Netflix's 'Bird Box' With Sandra Bullock and 'The Kominsky Method' TV Series". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ "Green Book – Watch New Clip". Filmoria.co.uk. October 16, 2018. Retrieved October 16, 2018.

- ^ Donnelly, Matt; Woerner, Meredith (November 9, 2018). "Viggo Mortensen Apologizes for Using N-Word at 'Green Book' Panel". Variety. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

- ^ "Green Book DVD Release Date". DVDs Release Dates.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (November 18, 2018). "'Crimes Of Grindelwald' Falls Short Stateside With $62M+ Debut, WB Celebrates Global Win As 'Fantastic Beasts' Series Hits $1B-Plus". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ Fuster, Jeremy (November 18, 2018). "'Green Book' Has Successful Start at Indie Box Office Before Wide Release". TheWrap. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (November 1, 2018). "Ralph Breaks The Internet' Tracking To $65M; 'Creed II' Eyeing $48M, 'Robin Hood' $17M In Thanksgiving B.O. Showdown". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- ^ a b D'Alessandro, Anthony (November 25, 2018). "'Ralph' Breaking The B.O. With $18.5M Weds., Potential Record $95M Five-Day; 'Creed II' Pumping $11.6M Opening Day, $61M Five-Day". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved November 25, 2018.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (December 2, 2018). "'Ralph' Breaking $25M+ 2nd Weekend; 'Grinch' Steals $202M+; 'Hannah Grace' $6M+ In Slow Post Thanksgiving Period – Update". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved December 3, 2018.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (December 9, 2018). "'Ralph' Keeps No. 1 Away From Greedy 'Grinch' For Third Weekend In A Row With $16M+ – Sunday Update". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (December 16, 2018). "'Spider-Verse' Raises $35M+ As 'The Mule' Kicks Up $17M+ In Pre-Christmas Period, But 'Mortal Engines' Breaks Down With $7M+". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved December 17, 2018.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (January 6, 2018). "'Aquaman' Still The Big Man At The B.O. With $30M+; 'Escape Room' Packs In $17M+ – Early Sunday Update". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved January 6, 2019.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (January 20, 2018). "'Glass' Now Looking At Third-Best MLK Weekend Opening With $47M+". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved January 20, 2019.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (January 27, 2018). "'Glass' Leads Again At Weekend B.O., But Only A Handful Of Oscar Best Picture Noms Will See Boost". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- ^ Rubin, Rebecca (February 16, 2020). "Parasite' Enjoys Record Box Office Boost After Oscar Wins". Variety. Variety Media, LLC. Retrieved November 10, 2021.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (March 3, 2019). "'Dragon 3' Keeps The Fire Burning At No. 1 With $30M Second Weekend; 'Madea' Mints $27M". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

- ^ "Green Book enjoys box office boost after Oscar win". Film Industry Network. March 9, 2019.

- ^ Tartaglione, Nancy (March 7, 2019). "'Green Book' Drives Past $200M Worldwide; Oscar Winner At $27M In China". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ Faughnder, Ryan (March 14, 2018). "'Captain Marvel' is likely to crush 'Wonder Park' at the box office". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ Tartaglione, Nancy (April 1, 2019). "'Green Book' Logs $300M+ At Worldwide Box Office; Tops $70M In China". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved April 1, 2019.

- ^ "Green Book (2018)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Retrieved November 29, 2022.

- ^ "Green Book reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved February 9, 2019.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (February 22, 2018). "'Which Film Stands To Gain The Most At The B.O. From An Oscar Best Picture Win? Perhaps None Of Them". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- ^ LaSalle, Mike (November 14, 2018). "Viggo Mortensen and Mahershala Ali achieve screen magic in 'Green Book'". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved November 22, 2018.

- ^ Pond, Steve (November 14, 2018). "'Green Book' Film Review: Viggo Mortensen and Mahershala Ali Take a Perilous Road Trip Through the Deep South". TheWrap. Retrieved November 22, 2018.

- ^ Hammond, Pete (December 15, 2018). "Notes On The Season: Quincy Jones Loves 'Green Book'". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved December 17, 2018.

- ^ McFarland, Melanie (December 30, 2018). "Hollywood still loves a white savior: "Green Book" and the lazy, feel-good take on race". Salon. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- ^ a b Nolfi, Joey (January 6, 2019). "Green Book wins Best Picture — Comedy or Musical at Golden Globes". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ Morris, Wesley (January 23, 2019). "Why Do the Oscars Keep Falling for Racial Reconciliation Fantasies?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

- ^ Abdul-Jabbar, Kareem (January 14, 2019). "Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: Why the 'Green Book' Controversies Don't Matter". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on January 15, 2019.

- ^ Lynn, Samara (November 29, 2018). "Family of Black Man, Don Shirley, Portrayed in 'The Green Book' Blasts Movie and Its 'Lies'". Black Enterprise. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ Fleming Jr, Mike (January 28, 2019). "Green Book's Real Tapes: Audio Of Doc Shirley And Tony Lip Vallelonga". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on January 28, 2019. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ a b Harris, Hunter (December 15, 2018). "Mahershala Ali Apologized to His Green Book Character's Family After Controversy". Vulture. Retrieved December 17, 2018.

- ^ Täht, Evelin; Mikkola, Atro (2022). A Rediscovered Trio. Pappus OÜ. ASIN B09TV5ZSMX.

- ^ "TIFF 2018 Awards: ‘Green Book’ Wins the People’s Choice Award, Upsetting ‘A Star Is Born’". IndieWire, September 16, 2018.

Bibliography

[edit]- Baltin, Steve (February 16, 2019). "Robert Plant's Friendly Role In 'Green Book' Soundtrack And Other Behind The Scenes Secrets". Forbes. An interview with director Peter Farrelly and composer Kris Bowers about the film's soundtrack.

External links

[edit]- 2018 films

- 2018 LGBTQ-related films

- 2018 biographical drama films

- 2018 drama films

- 2010s road comedy-drama films

- 2010s buddy comedy-drama films

- African-American comedy-drama films

- African-American LGBTQ-related films

- African-American-related controversies in film

- American biographical drama films

- American buddy comedy-drama films

- American LGBTQ-related films

- American road comedy-drama films

- Best Musical or Comedy Picture Golden Globe winners

- Best Picture Academy Award winners

- DreamWorks Pictures films

- Films about friendship

- Films about Italian-American culture

- Films about pianos and pianists

- Films about racism in the United States

- Films directed by Peter Farrelly

- Films featuring a Best Supporting Actor Academy Award–winning performance

- Films featuring a Best Supporting Actor Golden Globe winning performance

- Films scored by Kris Bowers

- Films set in 1962

- Films set in Alabama

- Films set in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Films set in Indiana

- Films set in Iowa

- Films set in Kentucky

- Films set in Manhattan

- Films set in Memphis, Tennessee

- Films set in Mississippi

- Films set in New Orleans

- Films set in North Carolina

- Films set in Ohio

- Films set in Pittsburgh

- Films set in the Bronx

- Films whose writer won the Best Original Screenplay Academy Award

- Films with screenplays by Peter Farrelly

- Gay-related films

- 2010s American films

- 2010s English-language films

- 2010s Italian-language films

- Participant (company) films

- Toronto International Film Festival People's Choice Award winners

- Universal Pictures films

- Lionsgate films

- English-language biographical drama films

- English-language road comedy-drama films

- English-language buddy comedy-drama films