Bradish Johnson

Bradish Johnson (April 22, 1811 – November 3, 1892) was an American industrialist and slave owner. He owned plantations and sugar refineries in Louisiana and a large distillery in New York City. In 1858 his distillery was at the heart of a scandal when an exposé in a weekly magazine accused it (and other distilleries) of producing altered and unsafe milk, called "swill milk", for sale to the public. The swill milk scandal helped to create the demand for consumer protection laws in the United States.

Early life and education

[edit]Bradish Johnson's father, William M. Johnson, was a sea captain from Nova Scotia. In 1795 he purchased land in Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana, along with a partner from Salem, Massachusetts named George Bradish. The partners built a sugar plantation there called "Magnolia", where they settled and began to produce sugar. In the 1830s, William Johnson moved his family to a new plantation four miles further up the Mississippi River, in Pointe à la Hache, Louisiana. He named his new plantation "Woodland".[1]

Bradish Johnson, born in 1811, was the third of four sons. He was named after his father's business partner, George Bradish. By 1820, Captain William Johnson had also begun purchasing property on the West side of Manhattan and had gone into the distillery and sugar refining business in New York.[2] Bradish Johnson, who was born in Louisiana, attended Columbia College in New York City, graduating in the class of 1831.[3] He then studied law and was admitted to the bar. When his father became ill, he abandoned the legal profession to enter the family business.[3]

Business

[edit]Johnson started out as a partner in the distilling company William Johnson and Sons. After his father's death, he went into business with a man named Moses Lazarus, the father of poet Emma Lazarus, as Johnson and Lazarus.[4] Upon the retirement of Lazarus, the firm was renamed Bradish Johnson and Sons. The Johnsons owned several properties, including a distillery at 244 Washington Street. The largest facility occupied two city blocks near the Hudson River, from Ninth Avenue to Eleventh Avenue between 15th and 16th Streets. The distillery was east of Tenth Avenue, while the cow barns and dairy were located west of Tenth.

Through his distilleries and his investments in real estate, Johnson became very wealthy. He became one of the directors of the Chemical Bank of New York when it was rechartered in 1844. He served as a director for the next twenty years.[5] Johnson was an innovator in the sugar industry, and his refinery was the first to "successfully make use of centrifugal machines in the manufacture of sugar".[1]

Johnson bought out his brother's share of the Woodland Plantation before the Civil War and became its sole owner.[6] He eventually purchased a number of other plantations in the area: Pointe Celeste, Bellevue, and the Orange Farm. He also acquired two plantations above New Orleans which he renamed after his married daughters: Whitney Plantation and Carroll Plantation.[3]

When Johnson's estate was settled in 1900, it included 31 pieces of New York real estate, which together added up to 78 acres. All the lots were purchased by a corporation formed by his heirs for a total of $4,769,100.[7]

"Swill milk" scandal

[edit]

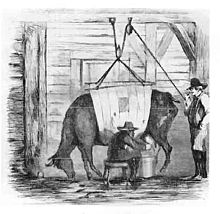

The Johnson & Lazarus distillery at 16th Street was the subject of a famous muckraking exposé by Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper in 1858.[8] Distilleries in 19th century New York had to dispose of the tons of organic waste they generated, and their solution was to feed the still hot mash to hundreds of sick old cows and then sell the milk. The cows were crowded into filthy stables, and were so sickly that some of them were reportedly held up by slings. The milk, referred to as "swill milk", was often cut with water and then thickened with chalk or flour. Swill milk was accused of being a major cause of infant mortality — it was sold from pushcarts all over the city, advertised, e.g., as farm-fresh milk from Orange County.[8]

Johnson was a supporter of the Tammany Hall politician Alderman Michael Tuomey, known as "Butcher Mike". Tuomey defended the distillers vigorously throughout the scandal — in fact, he was put in charge of the Board of Health investigation. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper staked out Johnson's mansion at 21st and Broadway, and reported that in the midst of the investigation, Tuomey was observed making late night visits. The Board of Health exonerated the distillers, but public outcry led to the passage of the first food safety laws in the form of milk regulations in 1862.[9]

Civil War years

[edit]Petitioning Lincoln

[edit]In 1863 Johnson took a leading part in the "Conservative Unionists", a group of businessmen with interests in the South who wanted occupied Louisiana let back into the Union with her 1852 constitution intact. They claimed that the state constitution had not been dissolved and the secession was illegal, so the President should allow the state back into the Union with slavery intact. Johnson and two other plantation owners made their argument in a letter to President Lincoln, reinforced by a personal visit. Lincoln was not impressed. In his dismissive response he wrote "I do not perceive how such committal could facilitate our military operations in Louisiana, I really apprehend it might be so used as to embarrass them."[10]

Johnson v. Dow

[edit]In 1863 Johnson brought a suit against a Union general. The suit claimed that in 1862 the occupying Union Army, under the command of General Neal S. Dow of the 13th Maine Regiment, 'took from Johnson's plantation twenty-five hogsheads of sugar, plundered the dwelling-house hereon and took one silver pitcher, one-half dozen silver knives, one-half dozen silver spoons, one fish knife, one-half dozen silver teaspoons and other articles.'

Johnson presented himself as a loyal citizen of the Union, residing in New York, who had simply been robbed by the Union Army. He was awarded $1750 in damages by the court. When Dow failed to pay him, he sued Dow in Dow's home state of Maine after the war. The case went all the way to the Supreme Court, which handed down a decision in 1876 against Johnson, pointing out that his holdings were in conquered territory during a time of war, and that it would be very hard to engage in warfare if the enemy could sue for damages. "Johnson v. Dow" became a hot topic of debate during the heated Tilden-Hayes Presidential election of 1876, as the country tried to figure out the confusing nature of the status of the defeated Confederate states.[11]

Woodland described

[edit]In 1863 the Union Army's "Office of Negro Labor" was sent to Woodland to investigate conditions there. They found that on the plantation "great ill feeling and discontent" existed. The slaves begged to be given permission to enlist in the Union Army. They complained that their rations were "unfairly curtailed" by the overseer and that he was "lecherous toward their women". After the inspectors had left, the overseer is said to have "harangued the Negroes, boasted of his unlimited power over them," and "used seditious and insulting language" towards the Union.[12] This report presents a very different picture from the one that appeared in Johnson's New York Times obituary and in the official history of the Chemical Corn Exchange Bank, which claimed that he had freed his slaves prior to the Emancipation Proclamation.[1][5]

Personal life

[edit]

Johnson married a New Yorker named Louisa Anna Lawrance around 1834. Together they had ten children. Their New York residence was located near fashionable Madison Square, at 21st Street on the short block between Broadway and Fifth Avenue.[13] In 1874 Johnson retired from business in New York and moved to New Orleans, where he had a new Italianate mansion built in the Garden District at 2343 Prytania Street. The house is now home to the Louise S. McGehee School. The family also had an estate in East Islip, on the South Shore of Long Island, NY, which is where Johnson died on November 3, 1892.[1] Johnson is interred at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York. He was a member of The Boston Club of New Orleans.

Legacy

[edit]After Johnson retired to New Orleans, his house at 21st and Broadway was home to the Lotos Club. In 1918 the Johnson heirs had an office building erected on the site. The building, at 921–925 Broadway, is called the Bradish Johnson Building.[14]

An image of "Woodland" was used on the logo of the liqueur Southern Comfort from 1934 to 2001.[15]

Since 1997 the site of the Johnson & Lazarus distillery at 16th Street and Ninth Avenue, later the factory of National Biscuit Company, has been home to Chelsea Market.

The house at Woodland Plantation has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places since 1998, and is operated as a bed and breakfast.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Obituary-Bradish Johnson" (PDF). New York Times. November 5, 1892. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ^ Barrett, Walter (2022). The Old Merchants of New York City. Frankfurt: Salzwasser Verlag. p. 183. ISBN 978-3-375-00249-7.

- ^ a b c "The Louisiana Planter and Sugar Manufacturer". The Louisiana Planter and Sugar Manufacturer. 9: 350. 12 Nov 1892. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ^ Bennett, Paula Bernat (2021). Poets in the Public Sphere: The Emancipatory Project of American Women's Poetry, 1800-1900. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 101. ISBN 0-691-02645-9.

- ^ a b Chemical Corn Exchange Bank (1913). History of the Chemical Bank. Private printing. pp. 104–106.

bradish johnson louisa lawrence marriage.

- ^ Barbara, Sillery (2006). The Haunting of Louisiana. Gretna: Pelican Publishing. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-56554-905-0.

- ^ "Bradish Johnson Holdings Bring $4,769,100 at Auction" (PDF). New York Times. October 12, 1900. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ a b "How We Poison Our Children" (PDF). New York Times. May 13, 1858. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ Wilson, Bee (2008). Swindled. Princeton University Press. p. 162.

- ^ Wetta, Frank Joseph (2013). The Louisiana Scalawags. LSU Press. pp. 74–75. ISBN 9780807147467.

- ^ Clifford, Phillip Greely (1922). Nathan Clifford, Democrat. G. P. Putnam. pp. 295–307. ISBN 9780795010934.

- ^ Young, Bette Roth (1997). Emma Lazarus and Her World. Jewish Publication Society. p. 49. ISBN 9780827606180.

- ^ In opposition to a plan to run a railroad up Fifth Avenue in 1885, group, including Cornelius Vanderbilt, Chauncey M. Depew, John Sloane, Bradish Johnson and William Waldorf Astor, organized the Association for the Protection of the Fifth Avenue Thoroughfare (Robert T. Swaine, The Cravath Firm And Its Predecessors: 1819-1947, 2006:413ff).

- ^ "Emporis". Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "SouthernComfort.com". Archived from the original on 27 June 2013. Retrieved 26 February 2013.