Borgund Stave Church

| Borgund Stave Church | |

|---|---|

| Borgund stavkyrkje | |

View of the church | |

| 61°02′50″N 7°48′44″E / 61.0472°N 07.8122°E | |

| Location | Lærdal Municipality, Vestland |

| Country | Norway |

| Denomination | Church of Norway |

| Previous denomination | Roman Catholic Church |

| Churchmanship | Evangelical Lutheran |

| Website | www |

| History | |

| Status | Former parish church |

| Founded | c. 1200 |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Museum |

| Architectural type | Stave church |

| Completed | c. 1200 |

| Closed | 1868 |

| Specifications | |

| Materials | Wood |

| Administration | |

| Diocese | Bjørgvin |

| Deanery | Sogn prosti |

| Parish | Lærdal |

| Type | Church |

| Status | Automatically listed |

| ID | 83933 |

Borgund Stave Church (Norwegian: Borgund stavkyrkje) is a former parish church initially of the Catholic Church and later the Church of Norway in Lærdal Municipality in Vestland county, Norway. It was built around the year 1200 as the village church of Borgund, and belonged to Lærdal parish (part of the Sogn prosti (deanery) in the Diocese of Bjørgvin) until 1868, when its religious functions were transferred to a "new" Borgund Church, which was built nearby. The old church was restored, conserved and turned into a museum. It is funded and run by the Society for the Preservation of Ancient Norwegian Monuments, and is classified as a triple-nave stave church of the Sogn-type. Its grounds contain Norway's sole surviving stave-built free-standing bell tower.[1][2]

Construction

[edit]Borgund Stave Church was built sometime between 1180 and 1250 AD with later additions and restorations. Its walls are formed by vertical wooden boards, or staves, hence the name "stave church." The four corner posts are connected to one another by ground sills, resting on a stone foundation.[3] The intervening staves rise from the ground sills; each is tongued and grooved, to interlock with its neighbours and form a sturdy wall.[4] The exterior timber surfaces are darkened by protective layers of tar, distilled from pine.

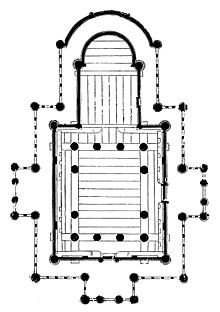

Borgund Stave Church is built on a basilica plan, with reduced side aisles, and an added chancel and apse.[5] It has a raised central nave demarcated on four sides by an arcade. An ambulatory runs around this platform and into the chancel and apse, both added in the 14th century. An additional ambulatory, in the form of a porch, runs around the exterior of the building, sheltered under the overhanging shingled roof. The floor plan of this church resembles that of a central plan, double-shelled Greek cross with an apse attached to one end in place of the fourth arm. The entries to the church are in the three shorter arms of the cross.

Structurally, the building has been described as a "cube within a cube", each independent of the other. The inner "cube" is formed by continuous columns that rise from ground level to support the roof. The top of the arcade is formed by arched buttresses, knee jointed to the columns. Above the arcade, the columns are linked by cross-shaped, diagonal trusses, commonly dubbed "Saint Andrew's crosses"; these carry arched supports that offer the visual equivalent of a "second storey". While not a functional gallery, this is reminiscent of contemporary second story galleries of large stone churches elsewhere in Europe. Smaller beams running between these upper supporting columns help clamp everything firmly together. The weight of the roof is thus supported by buttresses and columns, preventing downward and outward movement of the stave walls.[6][7]

The roof beams are supported by steeply angled scissor trusses that form an "X" shape with a narrow top span and a broader bottom span, tied by a bottom truss to prevent collapse. Additional support is given by a truss that cuts across the "X", below the crossing point but above the bottom truss. The roof is steeply pitched, boarded horizontally and clad with shingles. The original outer roof would have been weatherproofed with boards laid lengthwise, rather than shingles. In later years wooden shingles became more common.[8] Scissor beam roof construction is typical of most stave churches.[9]

Dragons

[edit]

Borgund has tiered, overhanging roofs, topped at their intersection by a shingle-roofed tower or steeple that straddles the ridge. On each of its four gables is a stylised "dragon" head, swooping from the carved roof ridge crests,[10] Hohler remarks their similarity to the carved dragon heads found on the prows of Norse ships. Similar gable heads appear on small bronze church-shaped reliquaries common in Norway and Europe in this period.[10][11] Borgund's current dragon heads are possible 18th century replacements;[10] similar, original dragon heads remain on older structures, such as Lom Stave Church and nearby Urnes Stave Church.[12] Borgund is one of the only stave churches to have preserved its crested ridge caps. They are carved with openwork vine and entangled plant designs.[10]

The four outer dragon heads are perhaps the most distinctive of all non-Christian symbols adorning Borgund Stave Church. Their function is uncertain, and disputed; if pagan, they are recruited to the Christian cause in the battle between Good and Evil. They may have been intended to keep away evil spirits thought to threaten the church building; to ward off evil, rather than represent it.[13]

On the lower side panel of the steeple are four carved circular cutouts. The carvings are weather-beaten, tarred and difficult to decipher, and there is disagreement about what they symbolize. Some[who?] believe they represent the four evangelists, symbolised by an eagle, an ox, a lion and a man. Hauglid describes the carvings as "dragons that extend their heads over to the neighboring field's dragon and bite into it", and points out their similarity to carvings at Høre Stave Church.[14]

The church's west portal (the nave's main entrance), is surrounded by a larger carving of dragons biting each other in the neck and tail. At the bottom of the half-columns that flank the front entrance, two dragon heads spew vine stalks that wind upwards and are braided into the dragons above. The carving shares similarities with the west portal of Ål Stave Church, which also has kites[clarification needed] in a band braiding pattern, and follows the usual composition[clarification needed] in the Sogn-Valdres portals, a larger group of portals with very clear similarities. Bugge writes that Christian authority may have come to terms with such pagan and "wild scenes" in the church building because the rift could be interpreted as a struggle between good and evil; in Christian medieval art, the dragon was often used as a symbol of the devil himself but Bugge believes that the carvings were protective, like the dragon heads on the church roof.[13]

Interior

[edit]The church interior is dark, as not much daylight enters the building. Some of the few sources of natural light are narrow circular windows along the roof, examples of daylighting. It was supposed that the narrow apertures would prevent the entry of evil spirits. Three entrances are heavily adorned with foliage and snakes, and are only wide enough for one person to enter, supposedly preventing the entry of evil spirits alongside the churchgoers. The portals were originally painted green, red, black, and white.[15]

Most of the internal fittings have been removed. There is little in the building, apart from the row of benches that are installed along the wall inside the church in the ambulatory outside of the arcade and raised platform, a soapstone font, an altar (with 17th-century altarpiece), a 16th-century lectern, and a 16th-century cupboard for storing altar vessels. After the Reformation, when the church was converted for Protestant worship, pews, a pulpit and other standard church furnishings were included, however these have been removed since the building has come under the protection of the Fortidsminneforeningen (The Society for the Preservation of Norwegian Ancient Monuments).

The interior structure of the church is characterized by the twelve free-standing columns that support the nave's elevated central space. On the long side of the church there is a double interval between the second and third pillars, but with a half pillar resting on the lower bracing beam (the pier) which runs in between. The double interval provides free access from the south portal to the church's central compartment, which would otherwise have been obstructed by the middle bar. The tops of the poles are finished with grotesque, carved human and animal masks. The tie-bars are secured with braces in the form of St. Andrew's crosses with a sun - shaped center and carved leaf shapes along the arms. The crosses reappear in less ornate form as braces along the church walls. On the north and south sides of the nave, a total of eight windows let in small amounts of light, and at the top of the nave's west gable is a window of more recent date - probably from pre-Reformation times. On the south wall of the nave, the inauguration crosses are still on the inside of the wall. The interior choir walls and west portal have engraved figures and runes, some of which date to the Middle Ages. One, among the commonest of runic graffiti, reads "Ave Maria". An inscription by Þórir (Thor), written "in the evening at St. Olav's Mass" blames the pagan Norns for his problems; perhaps a residue of ancient beliefs, as these female beings were thought to rule the personal destinies of all in Norse mythology and the Poetic Edda.[16][17]

The medieval interior of the stave church is almost untouched, save for its restorations and repairs, though the medieval crucifix was removed after the Reformation. The original wooden floor and the benches that run along the walls of the nave are largely intact, together with a medieval stone altar and a box-shaped baptismal font in soapstone. The pulpit is from the period 1550–1570 and the altarpiece dates from 1654, while the frame around the tablet is dated to 1620.[18] The painting on the altarpiece shows the crucifixion in the centre, flanked by the Virgin Mary on the left and John the Baptist on the right. In the tympanum field, a white dove hovers on a blue background. Below the painting is an inscription with golden letters on a black background. A sacrament from the period 1550–1570 in the same style as the pulpit is also preserved. A restoration of the building was carried out in the early 1870s, led by the architect Christian Christie, who removed benches, a second-floor gallery with seating, a ceiling over the chancel, and various windows including two large windows on the north and south sides. As the goal was to return the church to pre-Reformation condition, all post-Reformation interior paintwork was also removed.[19]

Images from the 1990s show deer antlers hung on the lower, east-facing pillars.[20] A local story claims that this is all that remains of a whole stuffed reindeer, shot when it tried to enter during a Mass. A travelogue from 1668 claims that a reindeer was shot during a sermon "when it marched like a wizard in front of the other animal carcasses".[21]

Bell tower

[edit]To the south of the church is a free-standing stave-work bell tower that covers remnants of the mediaeval foundry used to cast the church bell. It was probably built in the mid-13th century. It is Norway's only remaining free-standing stave-work bell tower.[22][better source needed]It was given a new door around the year 1700 but this was removed and not replaced at some time between the 1920s and 1940s, leaving the foundry pit exposed. To preserve the interior, new walls were built as cladding on the outside of the stave walls in the 1990s.[19] One of the medieval bells is on display in the new Borgund church.

Management

[edit]In 1868 the building was abandoned as a church but was turned into a museum; this saved it from the commonplace demolition of stave churches in that period. A new Borgund Church was built in 1868 a short distance south of the old church. The old church has not been formally used for religious purposes since that year. Borgund Stave Church was bought by the Society for the Preservation of Ancient Norwegian Monuments in 1877. The first guidebook in English for the stave church was published in 1898. From 2001, the Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage has funded a program to research, restore, conserve and maintain stave churches.[23]

Legacy

[edit]The church served as an example for the reconstruction of the Fantoft Stave Church in Fana, Bergen, in 1883 and for its rebuilding in 1997. The Gustav Adolf Stave Church in Hahnenklee, Germany, built in 1908, is modeled on the Borgund church. Four replicas exist in the United States, one at Chapel in the Hills, Rapid City, South Dakota,[24] another owned by Timothy Mellon in Lyme, Connecticut,[25] the third on Washington Island, Wisconsin,[26] and the fourth in Minot, North Dakota at the Scandinavian Heritage Park.[27]

Gallery

[edit]-

Picture from the work "Norge fremstillet i Tegninger" from 1848 by Christian Tønsberg

-

The picture is taken from the National Library's picture collection Borgund Stave Church, Lærdal, Sogn og Fjordane

-

Picture taken from a book edited by J. C. C. Dahl, landscape painter and professor at the K. S. Academy of Fine Arts in Dresden and Leipzig, 1837

-

Picture taken in the period 1880 - 1890

-

Stavkirken, Borgund, Martinus Rørbye, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, København, 1833

-

Borgund Stave Church in Lærdalen

-

Lion on arch decoration from Borgund Stave Church

-

Entranceway through pillared arch, Borgund Stave Church

-

Borgund Stave Church, the "new" Borgund Church, and the visitor center in the back

-

Picture of Borgund Church with visible daylighting windows

See also

[edit]- List of churches in Bjørgvin

- Runic inscription N 351

- Washington Island Stavkirke (Modeled after The Borgund Stave Church)

References

[edit]- ^ "Borgund stavkyrkje". Kirkesøk: Kirkebyggdatabasen. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- ^ "Oversikt over Nåværende Kirker" (in Norwegian). KirkeKonsulenten.no. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- ^ "Borgund Stave Church". Fortidsminneforeningen (The Society for the Preservation of Norwegian Ancient Monuments). Archived from the original on 17 September 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ^ Hauglid (1970), p. 99.

- ^ Hauglid (1970), p. 32.

- ^ Hauglid (1970), p. 104.

- ^ Sheldon, Gwendolyn, "The Origin of the Norwegian Stave Church" at the Third Annual North American Interdisciplinary Conference on Medieval Icelandic Studies, Cornell University, May 2008, pp. 3–4

- ^ Hauglid (1970), p. 12.

- ^ Hauglid (1970)

- ^ a b c d Hohler (1999), p. 69.

- ^ Anker og Havran (2005), s. 152

- ^ Hauglid (1970), p. 13

- ^ a b Bugge, Gunnar og Mezzanotte, Bernardino (1994). Stavkirker. Oslo: Grøndahl Dreyer. ISBN 82-504-2072-1.

- ^ Hauglid (1973), s. 267

- ^ Ching, Francis D. K. (2017). A global history of architecture. Mark Jarzombek, Vikramaditya Prakash (Third ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey. ISBN 978-1-118-98161-0. OCLC 971615732.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ MacLeod, Mindy; Mees, Bernard (2006), Runic Amulets and Magic Objects, Woodbridge: Boydell Press, p. 39, ISBN 1-84383-205-4

- ^ Zilmer, Kristel. “Words in Wood and Stone: Uses of Runic Writing in Medieval Norwegian Churches.” Viking and Medieval Scandinavia, vol. 12, 2016, pp. 199–227. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/48501802. Accessed 9 Dec. 2022.

- ^ "Fortidsminneforeningen avdeling Sogn og Fjordane (Borgund stavkirke)". Archived from the original on 30 July 2007. Retrieved 23 February 2006.

- ^ a b "Borgund stavkyrkje – Norges Kirker". norgeskirker.no.

- ^ Anker (1997), s. 71

- ^ Storsletten (1995), s. 20

- ^ "Borgund stavkyrkje". Fortidsminneforeningen. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ "Borgund Stave Church". Stavechurch.com. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "History of the Chapel in the Hills". Chapel in the Hills. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ^ "Borgund Stave Church replica Lyme Connecticut". Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ Blei, Norbert. "Stavkirke". Washington Island. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ "Scandinavian Heritage Association – Minot, North Dakota".

Bibliography

[edit]- Bugge, Gunnar (1981). Stavkirkene i Norge. Oslo. ISBN 82-09-01890-6.

- Bugge, Gunnar og Mezzanotte, Bernardino (1994). Stavkirker. Oslo: Grøndahl Dreyer. ISBN 82-504-2072-1.

- Hauglid, Roar; trans. R. I. Christophersen (1970). Norwegian Stave Churches. Oslo: Dreyers Forlag.

- Hohler, Erla Bergendahl (1999). Norwegian Stave Church Sculpture. Vol. I. Oslo: Scandinavian University Press. ISBN 978-82-00-12748-2.

External links

[edit]- Borgund stave church in Stavkirke.org (in Norwegian)

- Borgund stave church in Fortidsminneforeningen

- Fortidsminneforeninga's stave church pages (in Norwegian) (there are also English and German pages)

- Replica in Rapid City

- Information about Borgund stave church (in English)