Song of Songs

| |||||

| Tanakh (Judaism) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Old Testament (Christianity) | |||||

|

|

|||||

| Bible portal | |||||

The Song of Songs (Biblical Hebrew: שִׁיר הַשִּׁירִים, romanized: Šīr hašŠīrīm), also called the Canticle of Canticles or the Song of Solomon, is a biblical poem, one of the five megillot ("scrolls") in the Ketuvim ('writings'), the last section of the Tanakh. It is unique within the Hebrew Bible: it shows no interest in Law or Covenant or the God of Israel, nor does it teach or explore wisdom, like Proverbs or Ecclesiastes—although it does have some affinities to wisdom literature, as the ascription to the 10th-century BCE King of Israel Solomon indicates. Instead, it celebrates sexual love, giving "the voices of two lovers, praising each other, yearning for each other, proffering invitations to enjoy".[1][2]

The two lovers are in harmony, each desiring the other and rejoicing in sexual intimacy. Modern scholarship tends to hold that the lovers in the Song are unmarried,[3][4] which accords with its near ancient Near East context.[5] The women of Jerusalem form a chorus to the lovers, functioning as an audience whose participation in the lovers' erotic encounters facilitates the participation of the reader.[6]

Marvin H. Pope, in his commentary, quotes scholars who believe the Song would have been ritually performed as part of ancient fertility cults and that it is "suggestive of orgiastic revelry".[7] Though scholars have differed in assessing when it was written, with estimates ranging from the 10th to 2nd century BCE, linguistic analysis suggest an origin in the 3rd century.

In modern Judaism, the Song is read on the Sabbath during the Passover, which marks the beginning of the grain-harvest as well as commemorating the Exodus from Biblical Egypt.[8] Jewish tradition reads it as an allegory of the relationship between God and Israel. In Christianity, it is read as an allegory of Christ and his bride, the Church.[8][9]

Structure

[edit]There is widespread consensus that, although the book has no plot, it does have what can be called a framework, as indicated by the links between its beginning and end.[10] Beyond this, however, there appears to be little agreement: attempts to find a chiastic structure have not found acceptance, and analyses dividing the book into units have employed various methods, yielding diverse conclusions.[11]

The following indicative schema is from Kugler and Hartin's An Introduction to The Bible:[12]

- Introduction (1:1–6)

- Dialogue between the lovers (1:7–2:7)

- The woman recalls a visit from her lover (2:8–17)

- The woman addresses the daughters of Zion (3:1–5)

- Sighting a royal wedding procession (3:6–11)

- The man describes his lover's beauty (4:1–5:1)

- The woman addresses the daughters of Jerusalem (5:2–6:4)

- The man describes his lover, who visits him (6:5–12)

- Observers describe the woman's beauty (6:13–8:4)

- Appendix (8:5–14)

Title

[edit]The introduction calls the poem "the song of songs",[13] a phrase that follows an idiomatic construction commonly found in Scriptural Hebrew to indicate the object's status as the greatest and most beautiful of its class (as in Holy of Holies).[14] The work is also referred to as the "Song of Solomon", meaning the song 'of', 'by', 'for', or '[dedicated] to' Solomon.[15]

Summary

[edit]The poem proper begins with the woman's expression of desire for her lover and her self-description to the "daughters of Jerusalem": she insists on her sun-born blackness, likening it to the "tents of Kedar" (nomads) and the "curtains of Solomon". A dialogue between the lovers follows: the woman asks the man to meet; he replies with a lightly teasing tone. The two compete in offering flattering compliments ("my beloved is to me as a cluster of henna blossoms in the vineyards of En Gedi", "an apple tree among the trees of the wood", "a lily among brambles", while the bed they share is like a forest canopy). The section closes with the woman telling the daughters of Jerusalem not to stir up love such as hers until it is ready.[16]

The woman recalls a visit from her lover in the springtime. She uses imagery from a shepherd's life, and she says of her lover that "he pastures his flock among the lilies".[16]

The woman again addresses the daughters of Jerusalem, describing her fervent and ultimately successful search for her lover through the night-time streets of the city. When she finds him she takes him almost by force into the chamber in which she was conceived.[a] She reveals that this is a dream, seen on her "bed at night", and ends by again warning the daughters of Jerusalem "not to stir up love until it is ready".[16]

The next section reports a royal wedding procession. Solomon is mentioned by name, and the daughters of Jerusalem are invited to come out and see the spectacle.[16]

The man describes his beloved: Her eyes are like doves, her hair is like a flock of goats, her teeth like shorn ewes, and so on from face to breasts. Place-names feature heavily: her neck is like the Tower of David, her smell like the scent of Lebanon. He hastens to summon his beloved, saying that he is ravished by even a single glance. The section becomes a "garden poem", in which he describes her as a "locked garden" (usually taken to mean that she is chaste). The woman invites the man to enter the garden and taste the fruits. The man accepts the invitation, and a third party tells them to eat, drink, "and be drunk with love".[16]

The woman tells the daughters of Jerusalem of another dream. She was in her chamber when her lover knocked. She was slow to open, and when she did, he was gone. She searched through the streets again, but this time she failed to find him and the watchmen, who had helped her before, now beat her. She asks the daughters of Jerusalem to help her find him, and describes his physical good looks. Eventually, she admits her lover is in his garden, safe from harm, and committed to her as she is to him.[16]

The man describes his beloved; the woman describes a rendezvous they have shared. (The last part is unclear and possibly corrupted.)[16]

The people praise the beauty of the woman. The images are the same as those used elsewhere in the poem, but with an unusually dense use of place-names, e.g., pools of Hebron, gate of Bath-rabbim, tower of Damascus, etc. The man states his intention to enjoy the fruits of the woman's garden. The woman invites him to a tryst in the fields. She once more warns the daughters of Jerusalem against waking love until it is ready.

The woman compares love to death and Sheol: love is as relentless and jealous as these two, and cannot be quenched by any force. She summons her lover, using the language used before: he should come "like a gazelle or a young stag upon the mountain of spices".[16]

Composition

[edit]The poem seems to be rooted in festive performance, and connections have been proposed with the "sacred marriage" of Ishtar and Tammuz.[17] It offers no clue to its author or to the date, place, or circumstances of its composition.[18] The superscription states that it is "Solomon's", but even if this is meant to identify the author, it cannot be read as strictly as a similar modern statement.[19] The most reliable evidence for its date is its language: Aramaic gradually replaced Hebrew after the end of the Babylonian exile in the late 6th century BCE, and the evidence of vocabulary, morphology, idiom and syntax clearly point to a late date, centuries after King Solomon to whom it is traditionally attributed.[20] It has parallels with Mesopotamian and Egyptian love poetry from the first half of the 1st millennium, and with the pastoral idylls of Theocritus, a Greek poet who wrote in the first half of the 3rd century BCE;[21][6][22] as a result of these conflicting signs, speculation ranges from the 10th to the 2nd centuries BCE,[18] with the language supporting a date around the 3rd century.[23] Other scholars are more skeptical about the idea that the language demands a post-exilic date.[24]

Debate continues on the unity or disunity of the book. Those who see it as an anthology or collection point to the abrupt shifts of scene, speaker, subject matter and mood, and the lack of obvious structure or narrative. Those who hold it to be a single poem point out that it has no internal signs of composite origins, and view the repetitions and similarities among its parts as evidence of unity. Some claim to find a conscious artistic design underlying it, but there is no agreement among them on what this might be. The question, therefore, remains unresolved.[25]

Genre

[edit]The consensus among contemporary scholars of the Bible is that the Song of Songs is an erotic poem, and not an elaborate metaphor.[26][27][28][29]

In his commentary for the Anchor Bible Series, Marvin H. Pope quotes scholars who believe that the Song described a fertility cult liturgy, rooted in the fertility cults of the ancient Near Eastern cultures of Mesopotamia and Canaan, as well as their sacred marriage rites and funeral feasts.[7]

J. Cheryl Exum wrote: "The erotic desire of its protagonists, everywhere evident in the Song, leads me, in conclusion, to the Song's unique contribution to the conceptualization of love in the Bible: its romantic vision of love".[30]

The historian and rabbi Shaye J. D. Cohen summarises:

Song of Songs [is a] collection of love poems sung by him to her and her to him: [– –] While authorship is ascribed to Solomon in its first verse and by traditionalists, [modern Bible scholarship] argues that while the book may contain ancient material, there is no evidence that Solomon wrote it.

[– –] What is a collection of erotic poems doing in the Hebrew Bible? Indeed, some ancient rabbis were uneasy about the book’s inclusion in the canon.[31]

Several scholars have also argued that, alongside its condition as love poetry, the Song of Songs also shares a number of features with Wisdom literature.[32] For instance, Jennifer L. Andruska argues that the Song employs a number of literary conventions typical of this didactic literature and that it combines features of both ancient Near Eastern love song and wisdom genres to produce a wisdom literature about romantic love, instructing readers to pursue what she describes as a particular type of 'wise love' relationship, modelled by the lovers of the poem.[33][34] Likewise, Katharine J. Dell notes a number of Wisdom motifs in the Song such as parallels between the lovers and the advices and conduct of Woman Wisdom and the Loose Woman of Proverbs, among others.[35]

Canonisation and interpretation

[edit]Judaism

[edit]

The Song was accepted into the Jewish canon of scripture in the 2nd century CE, after a period of controversy in the 1st century. This period of controversy was a result of many rabbis seeing this text as merely "secular love poetry, a collection of love songs gathered around a single theme",[36] and thus not worthy of canonization. In fact, "there is a tradition that even this book was considered as one to be excluded."[37] It was accepted as canonical because of its supposed authorship by Solomon and based on an allegorical reading where the subject matter was taken to be not sexual desire but God's love for Israel.[38][39][40] For instance, the famed first and second century Rabbi Akiva forbade the use of the Song of Songs in popular celebrations. He reportedly said, "He who sings the Song of Songs in wine taverns, treating it as if it were a vulgar song, forfeits his share in the world to come".[41] However, Rabbi Akiva famously defended the canonicity of the Song of Songs, reportedly saying when the question came up of whether it should be considered a defiling work, "God forbid! [...] For all of eternity in its entirety is not as worthy as the day on which Song of Songs was given to Israel, for all the Writings are holy, but Song of Songs is the Holy of Holies."[42]

Other rabbinic scholars who have employed allegorical exegesis in explaining the meaning of Song of Songs are Tobiah ben Eliezer, author of Lekach Tov,[43] and Zechariah ha-Rofé, author of Midrash ha-Hefez.[44] The French rabbi Rashi did not believe the Song of Songs to be an erotic poem.[45]

Song of Songs is one of the overtly mystical Biblical texts for the Kabbalah, which gave an esoteric interpretation on all the Hebrew Bible. Following the dissemination of the Zohar in the 13th century, Jewish mysticism took on a metaphorically anthropomorphic erotic element, and Song of Songs is an example of this. In Zoharic Kabbalah, God is represented by a system of ten sephirot emanations, each symbolizing a different attribute of God, comprising both male and female. The Shechina (indwelling Divine presence) was identified with the feminine sephira Malchut, the vessel of Kingship. This symbolizes the Jewish people, and in the body, the female form, identified with the woman in Song of Songs. Her beloved was identified with the male sephira Tiferet, the "Holy One Blessed be He", a central principle in the beneficent heavenly flow of divine emotion. In the body, this represents the male torso, uniting through the sephira Yesod of the male sign of the covenant organ of procreation.

Through beneficent deeds and Jewish observance, the Jewish people restore cosmic harmony in the divine realm, healing the exile of the Shechina with God's transcendence, revealing the essential unity of God. This elevation of the world is aroused from above on the Sabbath, a foretaste of the redeemed purpose of Creation. The text thus became a description, depending on the aspect, of the creation of the world, the passage of Shabbat, the covenant with Israel, and the coming of the Messianic age. "Lecha Dodi", a 16th-century liturgical song with strong Kabbalistic symbolism, contains many passages, including its opening two words, taken directly from Song of Songs.

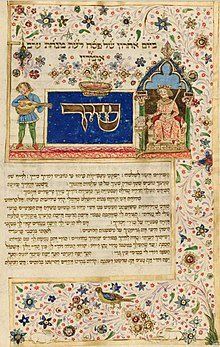

In modern Judaism, certain verses from the Song are read on Shabbat eve or at Passover, which marks the beginning of the grain harvest as well as commemorating the Exodus from Egypt, to symbolize the love between the Jewish people and their God. Jewish tradition reads it as an allegory of the relationship between God and Israel.[8] The entire Song of Songs in its original Hebrew is read in synagogues during the intermediate days of Passover. It is often read from a scroll similar to a Torah scroll in style. It is also read in its entirety by some at the end of the Passover Seder and is usually printed in most Hagadahs. Some Jews have the custom to recite the entire book prior to the onset of the Jewish Sabbath.

Christianity

[edit]

The literal subject of the Song of Songs is love and sexual longing between a man and a woman, and it has little (or nothing) to say about the relationship of God and man; in order to find such a meaning it was necessary to turn to allegory, treating the love that the Song celebrates as an analogy for the love between God and Church.[9] The Christian church's interpretation of the Song as evidence of God's love for his people, both collectively and individually, began with Origen.[46] Saint Gregory of Nyssa wrote fifteen Homilies on the Song of Songs, which are considered the pinnacle of his biblical exegesis. In them, he compares the bride to the soul and the invisible groom to God: the finite soul is incessantly reaching out towards the infinite God and remains continually disappointed in this life due to the failure to achieve ecstatic union with the beloved, a vision which enraptures and can be achieved fully and perfectly only in life after death.[47][48] Similarly, following the allegoric interpretation of Ambrose of Milan,[49] Saint Augustine of Hippo stated that the Song of Songs represents the wedding between Jesus Christ and the Catholic Church, pure and virgin, within an ascetic context.[50]

Over the centuries the emphases of interpretation shifted, first reading the Song as a depiction of the love between Christ and Church, the 11th century adding a moral element, and the 12th century understanding of the Bride as the Virgin Mary, with each new reading absorbing rather than simply replacing earlier ones, so that the commentary became ever more complex.[51] These theological themes are not found explicitly in the poem, but they come from a theological reading. Nevertheless, what is notable about this approach is the way it leads to conclusions not found in the overtly theological books of the Bible.[52] Those books reveal an abiding imbalance in the relationship between God and man, ranging from slight to enormous; but reading Songs as a theological metaphor produces quite a different outcome, one in which the two partners are equals, bound in a committed relationship.[52]

In modern times the poem has attracted the attention of feminist biblical critics, with Phyllis Trible's foundational "Depatriarchalizing in Biblical Interpretation" treating it as an exemplary text, and the Feminist Companion to the Bible series edited by Athalya Brenner and Carole Fontaine devoting two volumes to it.[53][54]

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints specifically rejects the Song of Solomon as inspired scripture.[55]

Islam

[edit]Several Islamic apologists contend that the word mahmaddim in Song of Songs 5:16 mentions Muhammad.[56] Whereas most translators will render the first words of that verse in terms such as "His mouth is most sweet, he is altogether lovely (mahamaddim)." In his book Demystifying Islam, Muslim apologist Harris Zafar argues that the last word (Hebrew: מַחֲּמַדִּים, romanized: maḥămaddîm, lit. 'lovely'), with the plural suffix "-im" (which is occasionally used to indicate intensity, and is normally understood to do so for both of the adjectives in this verse),[57][58][59] expressing respect and greatness (as the plural form seems to do in the common Hebrew appellation of God, Elohim (pl. maiestatus)), should be translated "Muhammad", for the translation "His mouth is most sweet; he is Muhammad".[45][b] Some Christian Apologists, however, have countered this claim.[60][61][62]

Musical settings

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2019) |

Excerpts from the book have inspired composers to write vocal and instrumental compositions, including:

- "Chi e costei", a setting of Song of Songs 6:10 in Il Primo libro delle musiche a 1–2 voci e basso continuo (1618) by Francesca Caccini

- Symphoniae sacrae I (1629) by Heinrich Schütz

- A'l Mishkavi Baleylot for soprano and harp (1992) and Spring Calls for soprano and ensemble (2006) by Lior Navok

- Alex Weiser's After Shir Hashirim (2017) draws its inspiration from the text and cantillation of the Song of Songs.[63]

- Andrew Rose Gregory of The Gregory Brothers released the album The Song of Songs, with words and music based on the biblical text, with The Color Red Band in 2011.[64]

- Animals As Leaders's self-titled album includes a track titled "Song of Solomon".

- Asma Asmaton from the album Rapsodies by Vangelis and Irene Papas.[65]

- Κραταία ως θάνατος αγάπη in the album Magnus Eroticus (Μεγάλος Ερωτικός) by Manos Hadjidakis.[66]

- C'est un jardin secret... for solo viola (1976) by Tristan Murail

- Canticum Canticorum by Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina: 29 five-part a cappella pieces in fourth volume of motets. (1584)

- David Lang's "Just (After Song of Songs)" (2014) was premiered in 2014 by Trio Mediaeval and Garth Knox Saltarello Trio. The piece is featured in the film Youth by Paolo Sorrentino.

- Dieterich Buxtehude's Membra Jesu Nostri: Cantata VI, Vulnerasti Cor Meum. (1680)

- Eliza Gilkyson's "Rose of Sharon" on her album "Your town tonight" is based on her reading of Song of Songs in a hotel room Gideon Bible, as explained in her intro to the song.

- Flos Campi by Ralph Vaughan Williams, a suite for solo viola, small chorus and small orchestra (1925), each movement headed by a verse from the book

- J. S. Bach's Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme, BWV 140, while mainly based on the Parable of the Ten Virgins, also uses words and imagery from the Song of Songs.[67]

- John Zorn's "Shir Ha-Shirim" premiered in February 2008.[68] The piece is inspired by Song of Songs and is performed by an amplified quintet of female singers with female and male narrators performing the "Song of Solomon". A performance at the Guggenheim Museum in November 2008 featured choreography for paired dancers from the Khmer Arts Ensemble by Sophiline Cheam Shapiro.[69] In 2013 a new version featuring the five singers without the two narrators premièred in NYC at Alice Tully Hall and at the Jerusalem Sacred Music Festival and released on the album Shir Hashirim.

- Kate Bush's "Song of Solomon" from her album The Red Shoes (1993) includes lyrics which quote and reference the Song of Songs.[70]

- Le Cantique des Cantiques (1952) by Jean-Yves Daniel-Lesur

- Lyudov Streicher (1888–1958) composed a musical setting for the Song of Songs.[71]

- Nightstone (1979) for voice and piano by Arnold Rosner

- Rami Bar-Niv's Uri Tsafon (Song of Songs 4, 16: Awake, North Wind) (1972)[72]

- Song of Solomon (1989) by Steve Kilbey

- Subject of the song I Hate Heaven by The Residents, which is featured in their bible inspired album Wormwood.

- The chorus of Stephen Duffy's 1985 song "Kiss Me" was based on the comparison of wine to love in Song of Songs.

- The opening track "Glass" off of Bat For Lashes's 2009 album Two Suns begins with a line from the Song of Songs.[73]

- Song of Solomon (2017) classical wedding suite composition for orchestra, organ and two voices by Chris M. Allport

In popular culture

[edit]Art

[edit]

- Catherine L. Morris' 2009 collection The Song of Songs: A Love Poem Illustrated presents a series of paintings that visualize the book.[74]

- Egon Tschirch's (de) "Song of Solomon", a 1923 expressionist nineteen-picture cycle, was rediscovered in 2015.

- Marc Chagall's "Song of Songs", a five-painting cycle, is housed in the Marc Chagall Museum in Nice.

Theater and film

[edit]- In Carl Theodor Dreyer's Day of Wrath, a film about sexual repression in a puritanical Protestant family, the first few verses of Song of Songs chapter 2 are read aloud by the daughter Anne, but soon after her father forbids her to continue. The chapter's verse paraphrases Anne's own amorous adventures and desires.[75]

- Lillian Hellman's 1939 play The Little Foxes (and the 1941 film adaptation) gets its title from Song 2:15: "Take us the foxes, the little foxes, that spoil the vines: for our vines have tender grapes".[76]

- In The Woman in the Window (1944), the character played by Edward G. Robinson reads The Song of Songs prior to his romantic entanglement with Joan Bennett.

- Several works have taken their name from the phrase "the voice of the turtle", found in 2:10-2:13.

- The 1986 Malayalam classic film Namukku Parkkan Munthirithoppukal uses several verses from the Song of Songs which forms one of its major plot elements.

- The 2014 film The Song is based on the Song of Songs.[77]

- S. Ansky's play The Dybbuk contains a recitation of the Song of Songs by Khanan's father when he is a young yeshiva boy. This becomes a major plot point in the play as it allows for the two lovers to identify the promise of marriage that their fathers made as classmates before departing.

Novels

[edit]- In Elizabeth Smart's novel of prose poetry By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept, several lines of the Song are spoken by the protagonist while she undergoes police questioning about her relationship with her companion, poet George Barker.

- Leon Garfield's masterwork The Pleasure Garden (1976) concludes with a reading of the first three chapters of the Song.[78]

- Rose of Sharon (an epithet in the Song) is a major character in John Steinbeck's novel The Grapes of Wrath.

- The song is mentioned repeatedly in Sholem Aleichem's Jewish Children.[79]

- Toni Morrison's 1977 novel is entitled Song of Solomon.

See also

[edit]- Dead Sea Scrolls 4Q106, 4Q107, 4Q108, 6Q6, fragments including portions of the Song of Songs.

- Hortus conclusus

- Ivory tower

Notes

[edit]- ^ The action of the conception is attributed specifically and exclusively to the woman's mother.

- ^ Zafar claims that this word is otherwise translated "altogether lovely", which is not correct. The word mahamaddim represents "lovely" and is part of the phrase ve-kullo mahamaddim, where ve-kullo represents "altogether". Zafar does not explain how to read the word ve-kullo, and translating mahamaddim as he suggests would result not in "His mouth is most sweet; he is Muhammad" but "His mouth is most sweet; all of him is Muhammad."

- ^ Garrett 1993, p. 366.

- ^ Alter 2011, p. 232.

- ^ Andruska 2022, p. 202.

- ^ Alter, Robert (2015). Strong As Death Is Love: The Song of Songs, Ruth, Esther, Jonah, and Daniel, A Translation with Commentary. W. W. Norton & Company. p. PT23. ISBN 978-0-393-24305-5.

- ^ Andruska, J. L. (2021). "Unmarried Lovers in the Song of Songs". The Journal of Theological Studies. 72 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1093/jts/flab019. ISSN 0022-5185.

- ^ a b Exum 2012, p. 248.

- ^ a b Pope, Marvin H. (1995). Song of Songs. Yale University Press. pp. 24–25, 222. ISBN 978-0-300-13949-5.

- ^ a b c Sweeney 2011, p. unpaginated.

- ^ a b Norris 2003, p. 1.

- ^ Assis 2009, pp. 11, 16.

- ^ Assis 2009, pp. 16–18.

- ^ Kugler & Hartin 2009, p. 220.

- ^ Garrett 1993, p. 348.

- ^ Keel 1994, p. 38.

- ^ Brenner, A., 21. The Song of Solomon, in Barton, J. and Muddiman, J. (2001), The Oxford Bible Commentary Archived 2017-11-22 at the Wayback Machine, p. 429, accessed 6 April 2024

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kugler & Hartin 2009, pp. 220–22.

- ^ Loprieno 2005, p. 126.

- ^ a b Exum 2012, p. 247.

- ^ Keel 1994, p. 39.

- ^ Bloch & Bloch 1995, p. 23.

- ^ Bloch & Bloch 1995, p. 25.

- ^ Keel 1994, p. 5.

- ^ Hunt 2008, p. 5.

- ^ Exum, J. Cheryl (2016). "Unity, Date, Authorship and the 'Wisdom' of the Song of Songs". In Brooke, George J.; Hecke, Pierre van (eds.). Goochem in Mokum, Wisdom in Amsterdam: Papers on Biblical and Related Wisdom Read at the Fifteenth Joint Meeting of the Society for Old Testament Study and the Oudtestamentisch Werkgezelschap, Amsterdam July 2012. BRILL. p. 57. ISBN 978-90-04-31477-1.

- ^ Exum 2012, p. 3334.

- ^ Barton, John (1998). How the Bible Came to be. Presbyterian Publishing Corporation. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-664-25785-9. Retrieved 3 October 2023.

For example, most scholars think that the Song of Songs originated as a set of erotic poems of very high quality, which were only later treated as scriptural: this was achieved by regarding the lovers in the poems as representative, allegorically, of God and Israel (Jesus and the Church, in the Christian version of the allegory).

- ^ Hamilton, Adam (2014). Making Sense of the Bible: Rediscovering the Power of Scripture Today. HarperCollins. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-06-223497-1. Retrieved 3 October 2023.

most scholars see it as a bit of erotic poetry to remind us that God invented sexual desire, and it is a good gift.

- ^ Fant, Clyde E.; Reddish, Mitchell Glenn (2008). Lost Treasures of the Bible: Understanding the Bible Through Archaeological Artifacts in World Museums. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-8028-2881-1. Retrieved 3 October 2023.

The view of most scholars today is that the Song of Songs should be taken at face value as erotic love poetry celebrating human love and sexuality, rather than as a divine allegory.

- ^ Kling, David W. (2004). The Bible in History: How the Texts Have Shaped the Times. Oxford University Press. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-19-531021-4. Retrieved 5 October 2023.

The reigning consensus among contemporary scholars is that the Song is a collection of poems about human love.

- ^ Exum, J. Cheryl (2022). "Conceptualizing Love in the Song of Songs". In Van Hecke, Pierre; Van Loon, Hanneke (eds.). Where Is the Way to the Dwelling of Light?: Studies in Genesis, Job and Linguistics in Honor of Ellen van Wolde. Brill. p. 335. ISBN 978-90-04-53629-6.

- ^ Cohen, Shaye J.D. "The Hebrew Bible: Notes for Lecture 20" (PDF).

- ^ Andruska 2022, p. 203.

- ^ Andruska 2022, pp. 214–215.

- ^ Andruska, Jennifer L. (2019). Wise and Foolish Love in the Song of Songs. Brill. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-90-04-33100-6.

- ^ Dell, Katharine J. (2020). The Solomonic Corpus of 'Wisdom' and Its Influence. Oxford University Press. pp. 52–58. ISBN 978-0-19-886156-0.

- ^ Scolnic, Benjamin Edidin (1996). "Why Do We Sing the Song of Songs on Passover?". Conservative Judaism. 48: 53–54.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Freehof, Solomon B (1949). "The Song of Songs: A General Suggestion". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 39 (4): 399. doi:10.2307/1453261. JSTOR 1453261.

- ^ Avot of Rabbi Natan 1:4, "At first they buried [Song of Songs], until the Men of the Great Assembly arrived to explain it . . . as it says, 'Come my beloved, let us go forth to the field . . .'" Cf. b. Eruvin 31b for the Rabbinic homily on this verse, "'Come my beloved' - so the congregation of Israel said to the Holy One, blessed be He . . ."

- ^ Loprieno 2005, p. 107.

- ^ Japhet, Sara (2007). "Rashi's Commentary on the Song of Songs: The Revolution of Prashat and Its Aftermath" (PDF). Rashi: The Man and His Work: 199.

- ^ Phipps 1974, p. 85.

- ^ Schiffman 1998, pp. 119–20.

- ^ Jacobs, Jonathan (2015). "The Allegorical Exegesis of Song of Songs by R. Tuviah ben 'Eli'ezer—"Lekaḥ Tov", and Its Relation to Rashi's Commentary". Association for Jewish Studies (AJS) Review. 39 (1). University of Pennsylvania Press: 75–92. doi:10.1017/S0364009414000658. JSTOR 26375005. S2CID 164390241.

- ^ Qafiḥ, Yosef (1962). The Five Scrolls (Ḥamesh Megillot) (in Hebrew). Jerusalem: ha-Agudah le-hatsalat ginze Teman. pp. 13–ff. OCLC 927095961.

- ^ a b Zafar 2014, p. 24.

- ^ R. O. Lawson (1957). The Song of Songs: Commentary and Homilies. Ancient Christian Writers. Paulist Press. ISBN 978-0-809-10261-7.

- ^ "Homilies on the Song of Songs". Holy See.

- ^ Gregory of Nyssa; Claudio Moreschini. Homilies on the Song of Songs (PDF) (in Italian). Archived from the original on 2024-01-09. Retrieved 2024-01-12.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Asiedu, F. B. A. (2001). "The Song of Songs and the Ascent of the Soul: Ambrose, Augustine, and the Language of Mysticism". Vigiliae Christianae. 55 (3): 299. JSTOR 1584812.

- ^ De Civitate Dei, XVII, 20. As quoted in Nathalie Henry, The Lily and the Thorns : Augustine’s Refutation of the Donatist Exegesis of the Song of Songs, in Revue des Études Augustiniennes, 42 (1996), 255-266 (ivi p. 255)

- ^ Matter 2011, p. 201.

- ^ a b Kugler & Hartin 2009, p. 223.

- ^ Pardes 2017, p. 134.

- ^ Brenner & Fontaine 2000, p. passim.

- ^ Introduction to the Song of Solomon

- ^ Hess, Richard S.; Wenham, Gordon J. (1998). Make the Old Testament Live: From Curriculum to Classroom. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-8028-4427-9.

- ^ Gesenius, Wilhelm (1898). Gesenius' Hebrew Grammar. Clarendon Press. pp. 417–418.

- ^ Delitzsch, Franz (1891). Commentary on the Song of Songs and Ecclesiastes. T. & T. Clark. p. 124.

- ^ Ginsburg, Christian David (1857). The Song of Songs: Translated from the Original Hebrew with a Commentary, Historical and Critical. By Christian D. Ginsburg. Longman.

- ^ "Muhammad's name in Song of Songs 5:16?". www.answering-islam.org. Retrieved 2024-10-12.

- ^ "Is Muhammad Prophesied in the Song of Solomon? Pt. 1". www.answering-islam.org. Retrieved 2024-10-12.

- ^ "Is Muhammad Prophesied in the Song of Solomon? Pt. 2". www.answering-islam.org. Retrieved 2024-10-12.

- ^ "Cantata Profana Performs Gustav Mahler's Das Lied Von Der Erde – Concert Program" (PDF). YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. YIVO. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ "The Song of Songs, by Andrew Rose Gregory". Andrew Rose Gregory. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- ^ "A musical journey". www.nemostudios.co.uk. Retrieved 2023-08-21.

- ^ Miralis, Yiannis (2004). "Manos Hadjidakis: The Story of an Anarchic Youth and a "Magnus Eroticus"". Philosophy of Music Education Review. 12 (1): 43–54. ISSN 1063-5734. JSTOR 40327219.

- ^ Herz, Gerhard. Bach: Cantata No. 140. W. W. Norton.

- ^ Allan, J. (February 22, 2008). "Live – John Zorn Abron Arts Centre". Amplifier Magazine (review). Archived from the original on November 12, 2011. Retrieved December 29, 2008.

- ^ Smith, S (November 27, 2008). "An Unlikely Pairing on Common Ground". The New York Times..

- ^ "Song Of Solomon (the)". Kate Bush Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2021-04-04.

- ^ Weisser, Albert (1954). The Modern Renaissance of Jewish Music, Events and Figures, Eastern Europe and America. Bloch.

- ^ "Uri Tsafon". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-11-07.

- ^ "Bat for Lashes - Glass Lyrics on Genius". Genius.com. Retrieved 2022-12-23.

- ^ The Song of Songs: A Love Poem Illustrated, New Classic Books, 2009, ISBN 978-1-600-20002-1.

- ^ Bordwell, David (July 1992). The Films of Carl Theodor Dreyer. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-04450-0.

- ^ ben David, Solomon, "Song", KJV, The Bible, Bible gateway, 2:15.

- ^ "THE SONG Movie – The Story – Coming Soon to Digital HD + DVD". Thesongmovie.com. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- ^ Garfield, Leon (1976). The pleasure garden. Internet Archive. New York: Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-56012-7.

- ^ "LibriVox". Librivox.org. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

References

[edit]- Alter, Robert (2011). The Art of Biblical Poetry. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-02819-1.

- Andruska, Jennifer L. (2022). "The Song of Songs". In Dell, Katherine J.; Millar, Suzanna R.; Keefer, Arthur Jan (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Biblical Wisdom Literature. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-66581-0.

- Assis, Elie (2009). Flashes of Fire: A Literary Analysis of the Song of Songs. T & T Clark. ISBN 978-0-567-02764-1.

- Bloch, Ariel; Bloch, Chana (1995). The Song of Songs: A New Translation, With an Introduction and Commentary. Random House. ISBN 978-0-520-21330-2.

- Brenner, Athalya; Fontaine, Carole (2000). A Feminist Companion to Song of Songs. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-84127-052-4.

- Exum, J. Cheryl (2012). "Song of Songs". In Newsom, Carol Ann; Lapsley, Jacqueline E. (eds.). Women's Bible Commentary. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-23707-3.

- Garrett, Duane (1993). Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs. B&H. ISBN 978-0-8054-0114-1.

- Schiffman, Lawrence H. (1998). Texts and traditions : a source reader for the study of Second Temple and rabbinic Judaism. KTAV Pub. House. ISBN 0-88125-434-7.

- Hunt, Patrick (2008). Poetry in the Song of Songs: A Literary Analysis. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-1-4331-0465-7.

- Keel, Othmar (1994). The Song of Songs: A Continental Commentary. Fortress. ISBN 978-0-8006-9507-1.

- Kugler, Robert A.; Hartin, Patrick (2009). The Old Testament between theology and history: a critical survey. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-4636-5.

- Loprieno, Antonio (2005). "Searching for a common background: Egyptian love poetry and the Biblical Song of Songs". In Hagedorn, Anselm C. (ed.). Perspectives on the Song of Songs. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-017632-2.

- Matter, E. Anne (2011). The Voice of My Beloved: The Song of Songs in Western Medieval Christianity. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-0056-0.

- Norris, Richard Alfred (2003). The Song of Songs: Interpreted by Early Christian and Medieval Commentators. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2579-7.

- Pardes, Ilana (2017). "Toni Morrisom's Shulamites". In Sherwood, Yvonne (ed.). The Bible and Feminism: Remapping the Field. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-103418-3.

- Phipps, William E. (1974). "The Plight of the Song of Songs". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. XLII (1): 82–100. doi:10.1093/jaarel/xlii.1.82. ISSN 0002-7189.

- Sweeney, Marvin A. (2011). Tanak: A Theological and Critical Introduction to the Jewish Bible. Fortress. ISBN 978-1-451-41435-6.

- Zafar, Harris (2014). Demystifying Islam. New Delhi: Dev Publishers & Distributors.

External links

[edit]- The original Hebrew version, vowelized, with side-by-side English translation Archived 2013-04-15 at archive.today by Mamre Institute (Mechon Mamre)

- Full English text

- Song of Songs at Bible Gateway (various translations)

Song of Solomon public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Song of Solomon public domain audiobook at LibriVox