Blue Origin

| |

| Blue Origin | |

| Company type | Private |

| Industry | Aerospace and launch service provider |

| Founded | September 8, 2000 |

| Founder | Jeff Bezos |

| Headquarters | Kent, Washington, United States |

Number of locations | 11 (4 production facilities & 7 field offices) |

Area served | United States of America |

Key people | Dave Limp (CEO) |

| Products | New Shepard New Glenn Blue Moon Blue Ring Orbital Reef |

| Owner | Jeff Bezos |

Number of employees | 11,000 (2023)[1] |

| Subsidiaries |

|

| ASN | 55244 |

| Website | blueorigin.com |

Blue Origin Enterprises, L.P.,[2] commonly referred to as Blue Origin, is an American aerospace manufacturer and launch service provider. The company makes rocket engines for United Launch Alliance's Vulcan rocket and is currently operating its suborbital reusable New Shepard vehicle and its heavy-lift launch vehicle named New Glenn. It is developing the Blue Moon human lunar lander for NASA's Artemis program, and Orbital Reef space station in partnership with other companies.

Blue Origin was founded in 2000 by Jeff Bezos and kept a very low profile about its development in the beginning. Its motto is Gradatim Ferociter, Latin for "Step by Step, Ferociously".[3] At this time, Blue Origin was sustained by Bezos's private investment fund. Fifteen years later in 2015, the company first performed its uncrewed launch and landing of the New Shepard suborbital launch vehicle. In that year, Blue Origin also announced plans for its reusable New Glenn vehicle. In 2021, New Shepard performed the first crewed mission crossing the Kármán line at 100 kilometers in altitude, one of the crew is the company's founder Jeff Bezos. The company delivered its first BE-4 rocket engine to United Launch Alliance in January 2023.[4] In September 2023, Bob Smith was replaced by Dave Limp as the chief executive officer. Eric Berger from Ars Technica noted that there is a wide gulf of technical capability between Blue Origin and SpaceX and other competitiors. While SpaceX was launching hundreds of rockets to orbit, Blue Origin has launched none.[5]

Blue Origin has also been involved in many NASA contracts throughout its history. The company has bids for the Commercial Crew Program to develop a crewed capsule for the International Space Station and use of the Kennedy Space Center Launch Complex 39 (disputed and now used by SpaceX). Blue Origin (alongside Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and Draper) also submitted the Blue Moon lunar lander proposal for the Artemis program in 2020. It also contested NASA's award to SpaceX for developing Starship HLS for the Artemis program in 2021, which indirectly led to a contract for its Blue Moon lander in 2023.

History

[edit]The company was founded in 2000 by Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon.[6][7] Rob Meyerson joined the company in 2003 and served as the CEO before leaving the company in 2018.[8] Bob Smith served as CEO from 2018 to 2023.[9] The current CEO is Dave Limp.[10] Little is known about the company's activities in its early years. In 2006, the company purchased land for its New Shepard missions 30 miles North of Van Horn, Texas, United States called Launch Site One (LS1). In November 2006, the first test vehicle was launched, the Goddard rocket, which reached an altitude of 285 feet.[11]

After initiating the development of an orbital rocket system prior to 2012, and stating in 2013 on their website that the first stage would perform a powered vertical landing and be reusable, the company publicly announced their orbital launch vehicle intentions in September 2015. In January 2016, the company indicated that the new rocket would be many times larger than New Shepard. The company publicly released the high-level design of the vehicle and announced its name in September 2016 as "New Glenn". The New Glenn heavy-lift launch vehicle can be configured in both two-stage and three-stage variants. New Glenn is planned to launch in Q3 of 2024.[12]

On July 20, 2021, New Shepard performed its first crewed mission to sub-orbital space called Blue Origin NS-16. The flight lasted approximately 10 minutes and crossed the Kármán line. The passengers were Jeff Bezos, his brother Mark Bezos, Wally Funk, and Oliver Daemen, after the unnamed auction winner (later revealed to have been Justin Sun) dropped out due to a scheduling conflict. Subsequent New Shepard passenger and cargo missions were: Blue Origin NS-17, Blue Origin NS-18, Blue Origin NS-19, Blue Origin NS-20, Blue Origin NS-21 and Blue Origin NS-23.[13]

The company primarily employs an incremental approach from sub-orbital to orbital flight,[14] with each developmental step building on its prior work. The company moved into the orbital spaceflight technology development business in 2014, initially as a rocket engine supplier via a contractual agreement to build the BE-4 rocket engine, for major US launch system operator United Launch Alliance (ULA). United Launch Alliance (ULA) has said that the first flight of its Vulcan Centaur heavy-lift launch vehicle is scheduled to launch in Q4 of 2023. The heavy-lift launch vehicles main power is supported by two BE-4 engines. On June 7, 2023, United Launch Alliance (ULA) performed a Flight Readiness Firing of the Vulcan Centaur rocket at launch pad 41 at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Cape Canaveral, Florida, United States. The two BE-4 rocket engines worked as expected.[15]

In 2024, the company won its first NSSL contract. The vehicle to be used on the launches is New Glenn.[16]

Launch vehicles

[edit]

New Shepard

[edit]New Shepard is a fully reusable suborbital launch vehicle developed for space tourism. The vehicle is named after Alan Shepard, the first American astronaut in space. The vehicle is capable of vertical takeoff and landings and can carry humans and customer payloads to the edge of space.[17]

The New Shepard launch vehicle is a rocket that consists of a booster rocket and a crew capsule. The capsule can be configured to house up to six passengers, cargo, or a combination of both. The booster rocket is powered by one BE-3PM engine, which sends the capsule to an apogee (Sub-Orbital) of 100.5 kilometres (62.4 mi) and flies above the Kármán line, where passengers and cargo can experience a few minutes of weightlessness before the capsule returns to Earth.[18][19]

The launch vehicle is designed to be fully reusable, with the capsule returning to Earth via three parachutes and a solid rocket motor. The booster lands vertically on the same launchpad it took off from. The company has successfully launched and landed the New Shepard launch vehicle 26 times with 1 partial failure (deemed successful) and 1 failure. The launch vehicle has a length of 19.2 metres (63 ft), a diameter of 3.8 metres (12 ft) and a launch mass of 75 short tons (150,000 lb; 68,000 kg). The BE-3PM engine produces 490 kN of thrust at takeoff. New Shepard allows the company to significantly reduce the cost of space tourism.[20][21]

New Glenn

[edit]

New Glenn is a heavy-lift launch vehicle and is expected to launch in Q3 of 2024 on the EscaPADE mission. The launch date has been set back because of numerous delays. Named after NASA astronaut John Glenn, design work on the vehicle began in early 2012. Illustrations of the vehicle, and the high-level specifications, were initially publicly unveiled in September 2016. The full vehicle was first unveiled on a launch pad on February 21, 2024.[22] The rocket has a diameter of 7 meters (23 ft), and its first stage is powered by seven BE-4 engines. The fairing is claimed to have twice the payload volume of "any commercial launch system" and to be the biggest payload fairing in the world.[23]

Like the New Shepard, New Glenn's first stage is also designed to be reusable. In 2021, the company initiated conceptual design work on approaches to potentially make the second stage reusable as well, with the project codenamed "Project Jarvis".[24]

NASA announced on February 9, 2023, that it had selected the New Glenn heavy-lift launch vehicle for the launch of two Escape and Plasma Acceleration and Dynamics Explorers (ESCAPADE) spacecraft. The New Glenn heavy-lift launch vehicle will launch ESCAPADE[25][26] in Q2 of 2025 with the ESCAPADE spacecraft entering Mars's orbit approximately one year after launch.

In 2024, Blue Origin received funding from the USSF to assess New Glenn's ability to launch national security payloads.[27]

Blue Moon

[edit]In May 2019, Jeff Bezos announced plans for a crew-carrying lunar lander known as Blue Moon.[28] The standard version of the lander is intended to transport 3.6 t (7,900 lb) to the lunar surface, whereas a stretched tank variant could land up to 6.5 t (14,000 lb) on the Moon; both vehicles are designed to make a soft landing on the Moon's surface.

The lander will use the BE-7 hydrolox engine.[29] On May 19, 2023, NASA contracted Blue Origin to develop, test and deploy its Blue Moon landing system for the agency's Artemis V mission, which explores the Moon and prepares future crewed missions to Mars. The project includes an uncrewed test mission followed by a crewed Moon landing in 2029. The contract value is $3.4 billion.[30][31] In mid-2024, the company announced initial acceptance testing completion on the thrusters for the MK1 variant of the Blue Moon lander.[32]

Rocket engines

[edit]

BE-1

[edit]Blue Origin's first engine is a "simple, single-propellant engine" called the Blue Engine-1 (BE-1) which uses peroxide propellant and generates 8.9 kN (2,000 lbf) of thrust.[33]

BE-2

[edit]The Blue Engine-2 (BE-2) which is a bipropellant engine using kerosene and peroxide, produces 140 kN (31,000 lbf) of thrust.[33]

BE-3 (BE-3U and BE-3PM)

[edit]The BE-3 is a family of rocket engines made by Blue Origin with two variants, the BE-3U and BE-3PM. The rocket engine is a liquid hydrogen/liquid oxygen (LH2/LOX) cryogenic engine that can produce 490 kN (110,000 lbf) and 710 kN (160,000 lbf) of thrust, respectively. Early thrust chamber testing began at NASA Stennis[34] in 2013.[35] By late 2013, the BE-3 had been successfully tested on a full-duration sub-orbital burn, with simulated coast phases and engine relights, "demonstrating deep throttle, full power, long-duration and reliable restart all in a single-test sequence."[36] NASA has released a video of the test.[35] As of December 2013[update], the engine had demonstrated more than 160 starts and 9,100 seconds (2.5 h) of operation at the company's test facility near Van Horn, Texas.[36][37]

- The BE-3U is an open expander cycle variant of the BE-3. Two of these engines will be used to power the New Glenn heavy-lift launch vehicle's second stage. The amount of thrust the BE-3U produces is 710 kilonewtons (160,000 lbf).[38]

- The BE-3PM, uses a pump-fed engine design, with a combustion tap-off cycle to take a small amount of combustion gases from the main combustion chamber to power the engine's turbopumps. One engine is used to power the Propulsive Module (PM) of New Shepard. The amount of thrust the BE-3PM produces is 490 kilonewtons (110,000 lbf).[38] The rocket engine can be throttled to as low as 110 kN (25,000 lbf) for use in controlled vertical landings.

BE-4

[edit]The BE-4 is a liquid oxygen/liquified natural gas (LOX/LNG) rocket engine that can produce 2,400 kN (550,000 lbf) of thrust.[39]

In late 2014, the company signed an agreement with United Launch Alliance (ULA) to develop the BE-4 engine, for ULA's upgraded Atlas V and Vulcan Centaur rockets replacing the RD-180 Russian-made rocket engine. The newly developed heavy-lift launch vehicle will use two of the 2,400 kN (550,000 lbf) BE-4 engines on each first stage. The engine development program for the BE-4 began in 2011.[40]

On October 31, 2022, a Twitter post by the official Blue Origin account announced that the first two BE-4 engines had been delivered to ULA and were being integrated on a Vulcan rocket. In a later tweet, ULA CEO Tory Bruno said that one of the engines had already been installed on the booster, and that the other would be joining it momentarily.[41] On June 7, 2023, the two BE-4 rocket engines performed as expected when ULA performed a Flight Readiness Firing of the Vulcan Rocket at launch pad 41 at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Cape Canaveral, Florida.[42][43]

Vulcan Centaur launched for the first time on January 8, 2024, successfully carrying Astrobotic Technology's Peregrine lunar lander, the first mission on NASA's Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program using the BE-4 engine.[44]

BE-7

[edit]The BE-7 engine is a liquid oxygen/liquid hydrogen dual expander cycle engine currently under development, designed for use on Blue Moon.[45] The engine produces 44 kN (10,000 lbf) of thrust. Its first ignition tests were performed in June 2019, with thrust chamber assembly testing continuing through 2023.[46]

Pusher escape motor

[edit]The company partnered with Aerojet Rocketdyne to develop a pusher launch escape system for the New Shepard suborbital crew capsule. Aerojet Rocketdyne provides the Crew Capsule Escape Solid Rocket Motor (CCE SRM) while the thrust vector control system that steers the capsule during an abort is designed and manufactured by Blue Origin.[47][48]

Facilities

[edit]

The company has facilities across the United States which include five main locations and five field offices:[49]

- Kent, Washington (headquarters)

- Van Horn, Texas

- Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida

- Huntsville, Alabama

- Marshall Space Flight Center, Alabama

- Arlington, Virginia

- Denver, Colorado

- Los Angeles, California

- Phoenix, Arizona

- Washington, DC

The company’s headquarters is in Kent, Washington. Rocket development takes place at its headquarters. The company has continued to expand its Seattle-area offices and rocket production facilities since 2016, purchasing an adjacent 11,000 m2 (120,000 sq ft)-building.[50] In 2017, the company filed permits to build a new 21,900 m2 (236,000 sq ft) warehouse complex and an additional 9,560 m2 (102,900 sq ft) of office space.[51] The company established a new headquarters and R&D facility, called the O'Neill Building on June 6, 2020.[52][53]

Launch Site One (LSO)

[edit]Corn Ranch, commonly referred to as Launch Site One (LSO) is the company's launch site 30 miles north of Van Horn, Texas.[54] The launch facility is located at 31.422927°N 104.757152°W.[55]

In addition to the sub-orbital launch pad, Launch Site One (LSO) includes a number of rocket engine test stands and engine test cells are at the site to support the hydrolox, methalox and storable propellant engines. There are three test cells for the BE-3 and BE-4 engines. The test cells support full-thrust and full-duration burns, and one supports short-duration, high-pressure preburner tests.

Blue Engine

[edit]Engine production is located in Huntsville, Alabama, at a 600,000 square foot facility called, "Blue Engine". The companies website states that, "The world-class engine manufacturing facility in The Rocket City conduct[s] high rate production of the BE-4 and BE-3U engines.

The company is planning a third major expansion in Huntsville and the company was approved for the sale of 14.83 acres adjacent to its already sprawling campus at the price of $1.427 million.[56]

Orbital Launch Site (OLS)

[edit]The Orbital Launch Site (OLS) at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, develops rockets and conducts extensive testing. The company converted Launch Complex 36 (LC-36) to launch New Glenn into orbit[57] at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station. The facility was initially completed in 2020 and is being used for the construction of New Glenn prototypes, rocket testing, and designs.[58]

The company facility is situated on 306 acres of land assembled from former Launch Complexes 11, 36A, and 36B, along with using the adjacent Launch Complex 12 for storage. The land parcel used to build a rocket engine test stand for the BE-4 engine, a launch mount, called the Orbital Launch Site, (hence its name) and a reusable booster refurbishment facility for the New Glenn launch vehicle, which is expected to land on a drone ship and return to Port Canaveral for refurbishment. Manufacturing of "large elements, such as New Glenn's first and second stages as well as the payload fairings and other large components will be made nearby in Exploration Park, which is near the entrance to the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex on Merritt Island, Florida.[59]

In addition to their Florida operations, they have also been leased the greenfield of Space Launch Complex 9 (SLC-9) at Vandenberg Space Force Base, where they plan to construct a New Glenn launch pad to give the launch vehicle polar orbit and Sun-synchronous orbit capabilities.[60]

Other projects

[edit]Blue Ring (Space Truck Vehicle)

[edit]The Blue Ring vehicle was announced in October 2023 by Blue Origin. It will have its own engine and is meant to handle orbital logistics and delivery. In March 2024, in partnership with the United States Space Force, it was announced that the Blue Ring’s capabilities will be tested soon on a mission called DarkSky-1.[61]

Orbital Reef (commercial space station)

[edit]The company and its partners Sierra Space, Boeing, Redwire Space and Genesis Engineering Solutions won a $130 million award to jump-start the design of their Orbital Reef commercial space station. The project is envisioned as an expandable business park, with Boeing's Starliner and Sierra Space's Dream Chaser transporting passengers to and from low Earth orbit (LEO) for tourism, research and in-space manufacturing projects.[62]

Orbital Reef’s design will be modular in nature, to provide the greatest amount of customization and compatibility. It will reportedly be designed to accept docking from almost every in operation spacecraft like SpaceX Dragon 2, Soyuz (spacecraft), Dream Chaser, and Boeing Starliner. The initial modules will be: Life, Node, Core, and Research Modules.[63]

In 2024 NASA increased funding for Orbital Reef by $42 million, bringing the total award to $172 million.[64]

Nuclear rocket program

[edit]NASA plans to test spacecraft, engines and other propellent systems powered by nuclear fission no later than 2027 as part of the agency's effort to demonstrate more efficient methods of traveling through outer space for space exploration.[65] One benefit to using nuclear fission as a propellent for spacecraft is that nuclear-based systems can have less mass than solar cells which means a spacecraft could be smaller while using the same amount of energy more efficiently. Nuclear fission concepts that can power both life support and propulsion systems could greatly reduce the cost and flight time during space exploration.[66]

The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency awarded General Atomics, Lockheed Martin and Blue Origin contracts to fund and build nuclear spacecraft under the agency's Demonstration Rocket for Agile Cislunar Operations program or DRACO program. The company was awarded $2.9 million to develop spacecraft component designs.[67]

In partnership with Blue Origin, Ultra Safe Nuclear Corporation, GE Hitachi Nuclear Energy, GE Research, Framatome and Materion, USNC-Tech won a $5 million contract from NASA and the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) to develop a long range nuclear propulsion system called the Power Adjusted Demonstration Mars Engine, or PADME.[68]

Space Technology

[edit]NASA awarded $35 million to the company in 2023 for the company's work on lunar regolith to be used for solar powered systems on the moon. The company's website states that "Blue Alchemist is a proposed end-to-end, scalable, autonomous, and commercial solution that produces solar cells from lunar regolith, which is the dust and crushed rock abundant on the surface of the Moon. Based on a process called molten regolith electrolysis, the breakthrough would bootstrap unlimited electricity and power transmission cables anywhere on the surface of the Moon. This process also produces oxygen as a useful byproduct for propulsion and life support."

Gary Lai, chief architect of the New Shepard rocket said during the pathfinder awards at the Seattle Museum of Flight that [The company] "aims to be the first company that harvests natural resources from the moon to use here on Earth,” He also mentioned that the company is building a novel approach to extract outer space's vast resources.

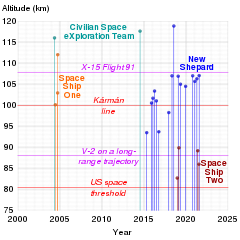

Blue Origin flight data

[edit]1

2

3

4

5

6

2005

2010

2015

2020

|

|

In the chart below, ♺ means "Flight Proven Booster"

| Flight No. | Date | Vehicle | Apogee | Outcome | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | March 5, 2005 | Charon | 315 ft (0.05 mi) | Success | Test Flight |

| 2 | November 13, 2006 | Goddard | 279 ft (0.05 mi) | Success | First rocket-powered test flight[69] |

| 3 | March 22, 2007 | Goddard ♺[70] | N/A | Success | Test Flight |

| 4 | April 19, 2007 | Goddard ♺[71] | N/A | Success | Test Flight |

| 5 | May 6, 2011 | PM2 (Propulsion Module)[72] | N/A | Success | Test Flight |

| 6 | August 24, 2011 | PM2 (Propulsion Module) ♺ | N/A | Failure | Test Flight |

| 7 | October 19, 2012 | New Shepard capsule | N/A | Success | Pad escape test flight[73] |

| 8 | April 29, 2015 | New Shepard 1 | 307,000 ft (58 mi) | Partial success | Flight to altitude 93.5 km, capsule recovered, booster crashed on landing[74] |

| 9 | November 23, 2015 | New Shepard 2 | 329,839 ft (62 mi) | Success | Sub-orbital spaceflight and landing[75] |

| 10 | January 22, 2016 | New Shepard 2 ♺ | 333,582 ft (63 mi) | Success | Sub-orbital spaceflight and landing of a reused booster[76] |

| 11 | April 2, 2016 | New Shepard 2 ♺ | 339,178 ft (64 mi) | Success | Sub-orbital spaceflight and landing of a reused booster[77] |

| 12 | June 19, 2016 | New Shepard 2 ♺ | 331,501 ft (63 mi) | Success | Sub-orbital spaceflight and landing of a reused booster: The fourth launch and landing of the same rocket. The company published a live webcast of the takeoff and landing.[78] |

| 13 | October 5, 2016 | New Shepard 2 ♺ | Booster:307,458 ft (58 mi)

Capsule:23,269 ft (4 mi) |

Success | Sub-orbital spaceflight and landing of a reused booster. Successful test of the in-flight abort system. The fifth and final launch and landing of the same rocket (NS2).[79] |

| 14 | December 12, 2017 | New Shepard 3 | Booster:322,032 ft(61 mi)

Capsule:322,405 ft(61 mi) |

Success | Flight to just under 100 km and landing. The first launch of NS3 and a new Crew Capsule 2.0.[80] |

| 15 | April 29, 2018 | New Shepard 3 ♺ | 351,000 ft (66 mi) | Success | Sub-orbital spaceflight and landing of a reused booster.[81] |

| 16 | July 18, 2018 | New Shepard 3 ♺ | 389,846 ft (74 mi) | Success | Sub-orbital spaceflight and landing of a reused booster, with the Crew Capsule 2.0–1 RSS H.G.Wells, carrying a mannequin. Successful test of the in-flight abort system at high altitude. Flight duration was 11 minutes.[82] |

| 17 | January 23, 2019 | New Shepard 3 ♺ | 351,000 ft (66 mi) | Success | Sub-orbital flight, delayed from December 18, 2018. Eight NASA research and technology payloads were flown.[83][84] |

| 18 | May 2, 2019 | New Shepard 3 ♺ | 346,000 ft (65 mi) | Success | Sub-orbital flight. Max Ascent Velocity: 2,217 mph (3,568 km/h),[85] duration: 10 minutes, 10 seconds. Payload: 38 microgravity research payloads (nine sponsored by NASA). |

| 19 | December 11, 2019 | New Shepard 3 ♺ | 343,000 ft (64 mi) | Success | Sub-orbital flight, Payload: Multiple commercial, research (8 sponsored by NASA) and educational payloads, including postcards from Club for the Future.[86][87][88] |

| 20 | October 13, 2020 | New Shepard 3 ♺ | 346,000 ft (65 mi) | Success | 7th flight of the same capsule/booster. Onboard 12 payloads include Space Lab Technologies, Southwest Research Institute, postcards and seeds for Club for the Future, and multiple payloads for NASA including SPLICE to test future lunar landing technologies in support of the Artemis program[89] |

| 21 | January 14, 2021 | New Shepard 4 | 350,858 ft (66 mi) | Success | Uncrewed qualification flight for NS4 rocket and "RSS First Step" capsule and maiden flight for NS4.[90] |

| 22 | April 14, 2021 | New Shepard 4 ♺ | 348,753 ft (66 mi) | Success | 2nd flight of NS4 with Astronaut Rehearsal. Gary Lai, Susan Knapp, Clay Mowry, and Audrey Powers, all Blue Origin personnel, are "stand-in astronauts". Lai and Powers briefly get in.[91] |

| 23 | July 20, 2021 | New Shepard 4 ♺ | 351,210 ft (66 mi) | Success | First crewed flight (NS-16). Crew: Jeff Bezos, Mark Bezos, Wally Funk, and Oliver Daemen.[92] |

| 24 | August 26, 2021[93] | New Shepard 3 ♺ | 347,434 ft (66 mi) | Success | Payload mission consisting of 18 commercial payloads inside the crew capsule, a NASA lunar landing technology demonstration installed on the exterior of the booster and an art installation installed on the exterior of the crew capsule.[94] |

| 25 | October 13, 2021 | New Shepard 4 ♺ | 341,434 ft (66 mi) | Success | Second crewed flight (NS-18). Crew: Audrey Powers, Chris Boshuizen, Glen de Vries, and William Shatner.[95] |

| 26 | December 11, 2021 | New Shepard 4 ♺ | 351,050 ft (66 mi) | Success | Third crewed flight (NS-19). Crew: Laura Shepard Churchley, Michael Strahan, Dylan Taylor, Evan Dick, Lane Bess, and Cameron Bess.[96] |

| 27 | March 31, 2022 | New Shepard 4 ♺ | 351,050 ft (66 mi) | Success | Fourth crewed flight (NS-20). Crew: Marty Allen, Sharon Hagle, Marc Hagle, Jim Kitchen, George Nield, and Gary Lai.[97] |

| 28 | June 4, 2022 | New Shepard 4 ♺ | 351,050 ft (66 mi) | Success | Fifth crewed flight (NS-21). Crew: Evan Dick, Katya Echazarreta, Hamish Harding, Victor Correa Hespanha, Jaison Robinson, and Victor Vescovo.[98] |

| 29 | August 4, 2022 | New Shepard 4 ♺ | 351,050 ft (66 mi) | Success | Sixth crewed flight (NS-22). Crew: Coby Cotton, Mário Ferreira, Vanessa O'Brien, Clint Kelly III, Sara Sabry, and Steve Young.[99] |

| 30 | September 12, 2022 | New Shepard 3 ♺ | 37,402 ft (7 mi) | Failure | Uncrewed flight with commercial payloads onboard (NS-23). A booster failure triggered the launch escape system during flight, and the capsule landed successfully. The Blue Origin incident investigation found that a thermal-structural failure occurred on the BE-3 nozzle leading to the launch failure.[100] |

| 31 | December 19, 2023 | New Shepard 4 ♺ | 107.060 km (66.5242 mi) | Success | Successful Return to Flight mission (NS-24) following failure of NS-23 more than a year prior. 33 payloads and 38,000 Club for the Future postcards from students around the world.[101] |

| 32 | 19 May 2024[102] | New Shepard 4 ♺ | c. 106 km[103] | Success | Seventh crewed New Shepard flight (NS-25). Crew of six included: Kenneth Hess, Sylvain Chiron, Mason Angel, Ed Dwight, Carol Schaller, Gopi Thotakura |

| 33 | 29 August 2024 | New Shepard 4 ♺ | Capsule 105.3 km (65.4 mi) | Success | Eighth crewed New Shepard flight (NS-26). Crew of six included: Ephraim Rabin, Nicolina Elrick, Eugene Grin, Rob Ferl, Karsen Kitchen, Eiman Jahangir |

| 34 | 23 October 2024 | New Shepard 5 | Capsule 101 km (63 mi) | Success | Flight Blue Origin NS-27. First flight of Propulsion Module NS5 and capsule RSS Kármán Line. 12 payloads and tens of thousands of Club for the Future postcards. |

| 35 | 22 November 2024, 15:30 UTC | New Shepard 4 ♺ | Capsule 105.3 km (65.4 mi) | Success | Ninth crewed New Shepard flight (Blue Origin NS-28). Crew of six included: – Emily Calandrelli – Sharon Hagle – Marc Hagle – Austin Litteral – James (J.D.) Russell – Henry (Hank) Wolfond |

NASA partnerships and funding

[edit]The company has contracted to do work for NASA on several development efforts. The company was awarded $3.7 million in funding by NASA in 2009 via a Space Act Agreement[104][105] under the first Commercial Crew Development (CCDev) program for development of concepts and technologies to support future human spaceflight operations.[106][107] NASA co-funded risk-mitigation activities related to ground testing of (1) an innovative 'pusher' escape system, that lowers cost by being reusable and enhances safety by avoiding the jettison event of a traditional 'tractor' Launch Escape System, and (2) an innovative composite pressure vessel cabin that both reduces weight and increases safety of astronauts.[104] This was later revealed to be a part of a larger system, designed for a bionic capsule, that would be launched atop an Atlas V rocket.[108] On November 8, 2010, it was announced that the company had completed all milestones under its CCDev Space Act Agreement.[109]

In April 2011, The company received a commitment from NASA for $22 million of funding under the CCDev phase 2 program.[110] Milestones included (1) performing a Mission Concept Review (MCR) and System Requirements Review (SRR) on the orbital Space Vehicle, which utilizes a bionic shape to optimize its launch profile and atmospheric reentry, (2) further maturing the pusher escape system, including ground and flight tests, and (3) accelerating development of its BE-3 LOX/LH2 440 kN (100,000 lbf) engine through full-scale thrust chamber testing.[111]

In 2012, NASA's Commercial Crew Program released its follow-on CCiCap solicitation for the development of crew delivery to ISS by 2017. The company did not submit a proposal for CCiCap, but reportedly continued work on its development program with private funding.[112] The company had a failed attempt to lease a different part of the Space Coast, when they submitted a bid in 2013 to lease Launch Complex 39A (LC39A) at the Kennedy Space Center – on land to the north of, and adjacent to, Cape Canaveral AFS – following NASA's decision to lease the unused complex out as part of a bid to reduce annual operation and maintenance costs. The companies bid was for shared and non-exclusive use of the LC39A complex such that the launchpad was to have been able to interface with multiple vehicles, and costs for using the launch pad were to have been shared across multiple companies over the term of the lease. One potential shared user in the companies proposed plan was United Launch Alliance (ULA). Commercial use of the LC39A launch complex was awarded to SpaceX, which submitted a bid for exclusive use of the launch complex to support their crewed missions.[113]

The company completed work for NASA on several small development contracts, receiving total funding of $25.7 million by 2013.[104][110] In September 2013 – before completion of the bid period, and before any public announcement by NASA of the results of the process – Florida Today reported that the company had filed a protest with the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) "over what it says is a plan by NASA to award an exclusive commercial lease to SpaceX for use of mothballed space shuttle launch pad 39A".[114] NASA had originally planned to complete the bid award and have the pad transferred by October 1, 2013, but the protest delayed a decision until the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) reached a decision on the protest.[114][115] SpaceX said that they would be willing to support a multi-user arrangement for pad 39A.[116] In December 2013, the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) denied the companies protest and sided with NASA, which argued that the solicitation contained no preference on the use of the facility as either multi-use or single-use. "The [solicitation] document merely [asked] bidders to explain their reasons for selecting one approach instead of the other and how they would manage the facility".[115] NASA selected the SpaceX proposal in late 2013 and signed a 20-year lease contract for Launch Pad 39A to SpaceX in April 2014.[117]

The company placed their first bid via the NASA Sustaining Lunar Development (SLD) competition to fund and develop a lunar lander capable of transporting astronauts to and from the lunar surface. The Blue Origin led team called the "National Team" included, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and Draper. On April 30, 2020, the company and its partners won a $579 million contract to start developing and testing an integrated Human Landing System (HLS) for the Artemis program to return humans to the Moon.[118][119] However, the Blue Origin led team lost their first bid to work for NASA's Artemis program and on April 16, 2021, NASA officially selected the Space Exploration Technologies Corp. (SpaceX) to develop, test and build their version of the Human Landing System (HLS) for Artemis missions 2 (II), 3 (III) and 4 (IV).

In early 2021, the company received over $275 million from NASA for lunar lander projects and sub-orbital research flights.[120]

The company then announced on December 6, 2022, that it had submitted a second bid via the NASA Sustaining Lunar Development (SLD) competition to fund and develop a second lunar lander capable for transporting astronauts to and from the lunar surface. The announcement fell within NASA's deadline for Sustaining Lunar Development (SLD) proposals. As with their first bid, the company is leading another team called the "National Team" which includes Draper, Boeing, Lockheed Martin, Astrobotic, Honeybee Robotics and Blue Origin.[121]

On May 19, 2023 NASA contracted the company to develop, test and deploy its Blue Moon landing system for the agency's Artemis V mission, which explores the Moon and prepares future manned missions to Mars. The project includes an unmanned test mission followed by a manned Moon landing in 2029. The contract value is $3.4 billion.[30][31]

Internal and additional U.S Government funding

[edit]By July 2014, Jeff Bezos had invested over $500 million into the company.[122] and the vast majority of further funding into 2016 was to support technology development and operations where a majority of funding came from Jeff Bezos' private investment fund. In April 2017, an annual amount was published showing that Jeff Bezos was selling approximately $1 billion in Amazon stock per year to invest in the company.[123] Jeff Bezos has been criticized for spending excessive amounts of his fortune on spaceflight.[124]

The company received $181 million from the United States Air Force for launch vehicle development in 2019. The company was also eligible to benefit from further grants totaling $500M as part of the U.S. Space Force Launch Services Agreement competition.[125] On November 18, 2022, the U.S. Space Systems Command announced that an agreement with the company that "paves the way" for the company's New Glenn rocket to compete for national security launch contracts once it completes its required flight certifications for Top Secret military payloads.

In an interview with Bob Smith by the financial Times in 2023, Smith said that the company had "hundreds of millions in revenue as well as billions of dollars in orders".[126]

The company is part of the DARPA Lunar Programs, specifically Luna10, an architecture study for lunar surface operations.[127]

Early test vehicles

[edit]Charon

[edit]

The company's first flight test vehicle, called Charon after Pluto's moon,[128] was powered by four vertically mounted Rolls-Royce Viper Mk. 301 jet engines rather than rockets. The low-altitude vehicle was developed to test autonomous guidance and control technologies, and the processes that the company would use to develop its later rockets. Charon made its only test flight at Moses Lake, Washington on March 5, 2005. It flew to an altitude of 96 m (316 ft) before returning for a controlled landing near the liftoff point.[129][130] As of 2016, Charon is on display at the Museum of Flight in Seattle, Washington.[131]

Goddard

[edit]The next test vehicle, named Goddard (also known as PM1), first flew on November 13, 2006. The flight was successful. A test flight for December 2 never launched.[132][133] According to Federal Aviation Administration records, two further flights were performed by Goddard.[134] Blue Engine 1, or BE-1, was the first rocket engine developed by the company and was used in the company's Goddard development vehicle.

PM2

[edit]Another early suborbital test vehicle, PM2, had two flight tests in 2011 in west Texas. The vehicle designation may be short for "Propulsion Module".[135] The first flight was a short hop (low altitude, VTVL takeoff and landing mission) flown on May 6, 2011. The second flight, August 24, 2011, failed when ground personnel lost contact and control of the vehicle. The company released its analysis of the failure nine days later. As the vehicle reached a speed of Mach 1.2 and 14 km (46,000 ft) altitude, a "flight instability drove an angle of attack that triggered [the] range safety system to terminate thrust on the vehicle". The vehicle was lost.[136] Blue Engine 2, or BE-2, was a pump-fed bipropellant engine burning kerosene and peroxide which produced 140 kN (31,000 lbf) of thrust.[137][138] Five BE-2 engines powered the company's PM-2 development vehicle on two test flights in 2011.[139]

See also

[edit]- Billionaire space race, Blue Origin vs. SpaceX vs. Virgin Galactic

References

[edit]- ^ Maidenberg, Micah (August 9, 2023). "Jeff Bezos' Blue Origin Plots Launch of Its Mega Rocket. Next Year. Maybe". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved August 9, 2023.

- ^ "Privacy Policy". Blue Origin. February 15, 2023. Retrieved December 1, 2023.

we at Blue Origin Enterprises, L.P. and our subsidiaries and affiliated companies, including Blue Origin, LLC, Blue Origin Alabama, LLC, Blue Origin Federation, LLC, Blue Origin Florida, LLC, Blue Origin Management, LLC, Blue Origin Texas, LLC, and Blue Origin International, LLC, Honeybee Robotics, LLC (referred together as "Blue Origin"

- ^ Boyle, Alan (October 24, 2016). "Gradatim Ferociter! Jeff Bezos explains Blue Origin's motto, logo … and the boots". GeekWire.

- ^ Erwin, Sandra (July 2, 2020). "Blue Origin delivers the first BE-4 engine to United Launch Alliance". SpaceNews. Retrieved October 28, 2024.

- ^ Berger, Eric (September 25, 2023). "Jeff Bezos finally got rid of Bob Smith at Blue Origin". Ars Technica. Retrieved October 28, 2024.

- ^ Staff Reporter (January 24, 2019). "Kent's Blue Origin racks up another successful New Shepard launch into space". Kent Reporter. Archived from the original on February 14, 2021. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ Berger, Eric (April 2, 2016). "Why Blue Origin's latest launch is a huge deal for cheap space access". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ Boyle, Alan (November 8, 2018). "Former Blue Origin president Rob Meyerson leaves Jeff Bezos' space venture". GeekWire. Archived from the original on March 1, 2019. Retrieved March 16, 2023.

- ^ "Jeff Bezos finally got rid of Bob Smith at Blue Origin". September 25, 2023.

- ^ "Departing Amazon exec Dave Limp to become Blue Origin CEO".

- ^ NSE (March 3, 2023). "The History of Blue Origin". New Space Economy. Archived from the original on May 21, 2023. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (April 13, 2023). "ESCAPADE confident in planned 2024 New Glenn launch". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- ^ "New Shepard Flight History". space.skyrocket.de. Archived from the original on May 29, 2023. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- ^ "Blue Origin NS-21 Mission Nears Launch". Aero-News Network. June 3, 2022. Archived from the original on December 16, 2022. Retrieved December 15, 2022.

- ^ "ULA test-fires first Vulcan rocket at Cape Canaveral – Spaceflight Now". Retrieved November 1, 2023.

- ^ Erwin, Sandra (June 13, 2024). "Blue Origin, SpaceX, ULA win $5.6 billion in Pentagon launch contracts". SpaceNews. Retrieved June 14, 2024.

- ^ "Blue Origin launches six thrill seekers to the edge of space – CBS News". www.cbsnews.com. June 4, 2022. Retrieved July 18, 2023.

- ^ "Three minutes of microgravity is worth the cost of a small house, if you're a scientist". Quartz. January 12, 2018. Archived from the original on June 29, 2023. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- ^ Watch Blue Origin New Shepard-22 Launch! (Full Flight), August 4, 2022, archived from the original on July 14, 2023, retrieved July 14, 2023

- ^ Johnson, Eric M.; Shepardson, David (July 12, 2021). "U.S. approves Blue Origin license for human space travel ahead of Bezos flight". Reuters. Archived from the original on June 1, 2023. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- ^ Frąckiewicz, Marcin (March 8, 2023). "The Economic Impacts of Blue Origin's Spaceflights". TS2 SPACE. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- ^ "Blue Origin Debuts New Glenn on Our Launch Pad".

- ^ Mooney, Justin (December 6, 2022). "Blue Origin conducts fairing testing amid quiet New Glenn progress". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on February 28, 2023. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- ^ Berger, Eric (August 24, 2021). "First images of Blue Origin's "Project Jarvis" test tank". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved May 6, 2023.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (February 10, 2023). "Blue Origin wins first NASA business for New Glenn". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved April 2, 2023.

- ^ "NASA picks Blue Origin's New Glenn to fly a science mission to Mars". Engadget. February 10, 2023. Archived from the original on April 2, 2023. Retrieved April 2, 2023.

- ^ Erwin, Sandra (January 24, 2024). "Blue Origin gets U.S. Space Force funding for New Glenn 'integration studies'". SpaceNews. Retrieved January 24, 2024.

- ^ Sheetz, Michael (May 9, 2019). "Jeff Bezos unveils Blue Origin's Blue Moon lunar lander for astronauts". CNBC. Archived from the original on May 10, 2019. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ Clark, Stephen (May 9, 2019). "Jeff Bezos unveils 'Blue Moon' lander". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on May 10, 2019. Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- ^ a b "NASA Selects Blue Origin as Second Artemis Lunar Lander Provider". May 19, 2023. Archived from the original on May 19, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ^ a b "Bezos' Blue Origin wins NASA astronaut moon lander contract to compete with SpaceX's Starship". CNBC. May 19, 2023. Archived from the original on May 19, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ^ "More and more hardware is arriving – paving our way to the Moon. Our gaseous hydrogen/oxygen reaction control system thrusters have completed acceptance testing ahead of installation on MK1, our first lunar lander. Our RCS thrusters enable different thrust levels for precision attitude control and are an important step toward humanity's sustained presence on the Moon. These will help us land anywhere on the Moon's surface, and best of all, they use propellants that can be manufactured from resources on the lunar surface!".

- ^ a b "Blue Origin Technology". Blue Origin. Archived from the original on January 10, 2018. Retrieved October 25, 2016.

- ^ "Updates on commercial crew development". NewSpace Journal. January 17, 2013. Archived from the original on January 19, 2013. Retrieved January 21, 2013.

- ^ a b Messier, Doug (December 3, 2013). "Video of Blue Origin Engine Test". Parabolic Arc. Archived from the original on December 6, 2013. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ a b Messier, Doug (December 3, 2013). "Blue Origin Tests New Engine in Simulated Suborbital Mission Profile". Parabolic Arc. Archived from the original on December 6, 2013. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ Blue Origin Tests New Engine Archived January 8, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Aviation Week, 2013-12-09, accessed September 16, 2014.

- ^ a b "Engines". Blue Origin. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2023.

- ^ "BE-4 Reverse Engineered". forum.nasaspaceflight.com. Archived from the original on April 20, 2023. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- ^ Achenbach, Joel (September 17, 2014). "Jeff Bezos's Blue Origin to supply engines for national security space launches". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 25, 2014. Retrieved September 27, 2014.

- ^ Boyle, Alan (October 31, 2022). "Blue Origin completes delivery of BE-4 rocket engines for first ULA Vulcan launch". GeekWire. Archived from the original on November 7, 2022. Retrieved November 7, 2022.

- ^ "ULA test-fires first Vulcan rocket at Cape Canaveral – Spaceflight Now". Archived from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ^ Live: Engine test firing for ULA's new Vulcan rocket, June 7, 2023, archived from the original on July 3, 2023, retrieved July 3, 2023

- ^ Foust, Jeff (January 8, 2024). "Vulcan Centaur launches Peregrine lunar lander on inaugural mission". Spacenews. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ^ Jeff Bezos unveils mock-up of Blue Origin's lunar lander Blue Moon Archived May 9, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. Loren Grush, The Verge. May 9, 2019.

- ^ Blue Origin fires up the engine of its future Moon lander for the first timeArchived May 9, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. Loren Grush, The Verge. June 20, 2019.

- ^ "Aerojet Motor Plays Key Role in Successful Blue Origin Pad Escape". Aerojet Rocketdyne. Archived from the original on May 14, 2018. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- ^ "Aerojet Rocketdyne Motor Plays Key Role in Successful Blue Origin In-Flight Crew Escape Test". Aerojet Rocketdyne. Archived from the original on May 14, 2018. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- ^ "Blue Origin Corporate Headquarters, Office Locations and Addresses | Craft.co". Archived from the original on April 4, 2023. Retrieved April 4, 2023.

- ^ Stile, Marc (October 20, 2016). "Bezos' rocket company, Blue Origin, is the new owner of an old warehouse in Kent". bizjournals.com. Puget Sound Business Journal. Archived from the original on March 2, 2017. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ^ "Jeff Bezos' Blue Origin space venture has plans for big expansion of Seattle-area HQ". Geekwire.com. February 22, 2017. Archived from the original on February 23, 2017. Retrieved August 11, 2017.

- ^ "Blue Origin officially opens its new HQ and R&D center". TechCrunch. January 7, 2020. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ "Blue Origin takes one giant leap across the street to space venture's new HQ in Kent". GeekWire. January 6, 2020. Archived from the original on November 7, 2020. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ "A Visit to see Blue Origin's Launch Site One". scopeviews.co.uk. Archived from the original on August 13, 2022. Retrieved June 9, 2023.

- ^ "31°25'22.5"N 104°45'25.8"W". 31°25'22.5"N 104°45'25.8"W. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- ^ "Price, Winford Hugh Protheroe, (born 5 Feb. 1926), City Treasurer, Cardiff City Council, 1975–83", Who's Who, Oxford University Press, December 1, 2007, doi:10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.u31450, archived from the original on July 17, 2023, retrieved June 9, 2023

- ^ Blue Origin's Rocket Factory Breaks Ground, June 2016 Archived July 10, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, accessed Feb 2022

- ^ "Blue Origin is leaving a substantial footprint in Florida". wtsp.com. October 13, 2021. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- ^ Davenport, Justin (May 8, 2023). "Blue Origin picking up the pace at the Cape". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on June 1, 2023. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- ^ "Staff Report" (PDF). California Coastal Commission. November 30, 2023. Retrieved August 31, 2024.

- ^ Malewar, Amit (March 27, 2024). "Blue Origin to test Blue Ring space truck capabilities on DarkSky-1 Mission". Inceptive Mind. Retrieved March 28, 2024.

- ^ "Orbital Reef | Home". www.orbitalreef.com. Archived from the original on October 26, 2021. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- ^ Zea, Luis; Warren, Liz; Ruttley, Tara; Mosher, Todd; Kelsey, Laura; Wagner, Erika (March 29, 2024). "Orbital Reef and commercial low Earth orbit destinations—upcoming space research opportunities". npj Microgravity. 10 (1): 43. Bibcode:2024npjMG..10...43Z. doi:10.1038/s41526-024-00363-x. ISSN 2373-8065. PMC 10980796. PMID 38553503.

- ^ "NASA Adjusts Agreements to Benefit Commercial Station Development - NASA". January 5, 2024. Retrieved April 14, 2024.

- ^ Roulette, Joey (January 25, 2023). "U.S. to test nuclear-powered spacecraft by 2027". Reuters. Archived from the original on April 7, 2023. Retrieved April 7, 2023.

- ^ Bardan, Roxana (January 23, 2023). "NASA, DARPA Will Test Nuclear Engine for Future Mars Missions". NASA. Archived from the original on May 26, 2023. Retrieved July 17, 2023.

- ^ Sheetz, Michael (April 12, 2021). "DARPA awards nuclear spacecraft contracts to Lockheed Martin, Bezos' Blue Origin and General Atomics". CNBC. Archived from the original on April 7, 2023. Retrieved April 7, 2023.

- ^ Boyle, Alan (January 24, 2023). "NASA joins forces with DARPA on effort to demonstrate nuclear rocket for Mars trips". GeekWire. Archived from the original on April 7, 2023. Retrieved April 7, 2023.

- ^ Graczyk, Michael (November 14, 2006). "Private space firm launches 1st test rocket". Associated Press. Archived from the original on January 7, 2007. Retrieved January 9, 2007.

- ^ Boyle, Alan (March 23, 2007). "Rocket Revelations". MSNBC. Archived from the original on January 19, 2008. Retrieved January 29, 2008.

- ^ "Recently Completed/Historical Launch Data". FAA AST. Archived from the original on March 11, 2008. Retrieved February 3, 2008.

- ^ "Recently Completed/Historical Launch Data". FAA AST. Archived from the original on March 11, 2008. Retrieved May 30, 2011.

- ^ "Blue Origin Conducts Successful Pad Escape Test". Blue Origin. October 22, 2012. Archived from the original on December 15, 2013. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ Harwood, Bill (April 30, 2015). "Bezos' Blue Origin completes first test flight of 'New Shepard' spacecraft". Spaceflight Now via CBS News. Archived from the original on June 9, 2021. Retrieved May 11, 2015.

- ^ Pasztor, Andy (November 24, 2015). "Jeff Bezos's Blue Origin Succeeds in Landing Spent Rocket Back on Earth". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on May 15, 2021. Retrieved November 24, 2015.

- ^ "Launch. Land. Repeat". Archived from the original on January 24, 2016. Retrieved January 23, 2016.

- ^ Calandrelli, Emily (April 2, 2016). "Blue Origin launches and lands the same rocket for a third time". Archived from the original on April 2, 2016. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- ^ Boyle, Alan (June 19, 2016). "Jeff Bezos' Blue Origin live-streams its spaceship's risky test flight". GeekWire. Archived from the original on June 20, 2016. Retrieved June 21, 2016.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (October 5, 2016). "Blue Origin successfully tests New Shepard abort system". SpaceNews. Retrieved October 5, 2016.

- ^ "Blue Origin flies next-generation New Shepard vehicle". SpaceNews.com. December 13, 2017. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ Clark, Stephen. "Video: Blue Origin flies New Shepard rocket for eighth time – Spaceflight Now". Archived from the original on May 15, 2021. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ Marcia Dunn (July 19, 2018). "Jeff Bezos' Blue Origin launches spacecraft higher than ever". Associated Press. Archived from the original on July 18, 2018. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- ^ Clark, Stephen. "Blue Origin reschedules New Shepard launch for Wednesday – Spaceflight Now". Archived from the original on January 20, 2019. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- ^ "Blue Origin New Shepard: Mission 10 (Q1 2019) – collectSPACE: Messages". www.collectspace.com. Archived from the original on January 23, 2019. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- ^ Clark, Stephen. "Blue Origin 'one step closer' to human flights after successful suborbital launch – Spaceflight Now". Archived from the original on May 2, 2019. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- ^ Boyle, Alan (December 8, 2019). "Watch Blue Origin send thousands of postcards to space and back on test flight". Archived from the original on December 10, 2019. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- ^ "New Shepard Mission NS-12 Updates". Blue Origin. Archived from the original on December 10, 2019. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- ^ "New Shepard sets reusability mark on latest suborbital spaceflight". SpaceNews.com. December 11, 2019. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ "New Shepard Mission NS-13 Launch Updates". Blue Origin. Archived from the original on September 22, 2020. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ "Blue Origin tests passenger accommodations on suborbital launch". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved January 14, 2021.

- ^ "Dress Rehearsal Puts Blue Origin Closer to Human Spaceflight". spacepolicyonline.com. Archived from the original on April 19, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- ^ Roulette, Joey (July 20, 2021). "Blue Origin successfully sends Jeff Bezos and three others to space and back". The Verge. Archived from the original on July 20, 2021. Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ Blue Origin [@blueorigin] (August 26, 2021). "Capsule, touchdown! A wholly successful payload mission for New Shepard. A huge congrats to the entire Blue Origin team on another successful flight" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ "New Shepard Payload Mission NS-17 to Fly NASA Lunar Landing Experiment and Art Installation". Blue Origin. Archived from the original on August 18, 2021. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ Maidenberg, Micah (October 13, 2021). "William Shatner Goes to Space on Blue Origin's Second Human Flight". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on June 17, 2022. Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ Beil, Adrian (December 11, 2021). "Blue Origin launches NS-19 with full passenger complement". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on June 15, 2022. Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ Wall, Mike (March 21, 2022). "Pete Davidson's spaceflight replacement is Blue Origin's Gary Lai". Space.com. Archived from the original on May 21, 2022. Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ "New Shepard Mission NS-21 to Fly Six Customer Astronauts, Including First Mexican-Born Woman to Visit Space". Blue Origin. May 9, 2022. Retrieved June 19, 2022.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "First Egyptian and Portuguese Astronauts to join Dude Perfect Cofounder on New Shepard's 22nd Flight". Blue Origin. Archived from the original on July 25, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ "Blue Origin NS-23 Findings". Blue Origin News. Archived from the original on May 31, 2023. Retrieved August 22, 2023.

- ^ "New Shepard's 24th Mission Will Carry 33 Science Payloads to Space". Blue Origin. Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- ^ "New Shepard's 25th Mission Includes America's First Black Astronaut Candidate". Blue Origin. Retrieved April 4, 2024.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (May 19, 2024). "Blue Origin resumes crewed New Shepard suborbital flights".

- ^ a b c "Blue Origin Space Act Agreement" (PDF). Nasa.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 22, 2013. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ "Blue Origin Space Act Agreement, Amendment One" (PDF). NASA. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 22, 2013. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ "NASA Selects Commercial Firms to Begin Development of Crew Transportation Concepts and Technology Demonstrations for Human Spaceflight Using Recovery Act Funds". press release. NASA. February 1, 2010. Archived from the original on February 3, 2010. Retrieved February 2, 2010.

- ^ Foust, Jeff. "Blue Origin proposes orbital vehicle". Newspacejournal.com. Archived from the original on April 26, 2015. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ "Commercial Crew and Cargo Program" (PDF). www.aiaa.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 10, 2010.

- ^ "Commercial Crew Development (CCDev) Round One Companies Have Reached Substantial Hardware Milestones in Only 9 Months, New Images and Data Show" (PDF). Commercialspaceflight.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 21, 2012. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ a b Morring, Frank Jr. (April 22, 2011). "Five Vehicles Vie To Succeed Space Shuttle". Aviation Week. Archived from the original on December 21, 2011. Retrieved February 23, 2011.

the CCDev-2 awards...and went to Blue Origin, Boeing, Sierra Nevada Corp. and Space Exploration Technologies Inc. (SpaceX).

- ^ "Blue Origin CCDev 2 Space Act Agreement" (PDF). Procurement.ksc.nasa.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 15, 2013. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ "NASA announces $1.1B in support for a trio of spaceships". Cosmicclog.nbcnews.com. Archived from the original on May 29, 2014. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ Matthews, Mark K. (August 18, 2013). "Musk, Bezos fight to win lease of iconic NASA launchpad". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on August 27, 2013. Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- ^ a b Messier, Doug (September 10, 2013). "Blue Origin Files Protest Over Lease on Pad 39A". Parabolic Arc. Archived from the original on September 25, 2013. Retrieved September 11, 2013.

- ^ a b Messier, Doug (December 12, 2013). "Blue Origin Loses GAO Appeal Over Pad 39A Bid Process". Parabolic Arc. Archived from the original on December 16, 2013. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (September 21, 2013). "A minor kerfuffle over LC-39A letters". Space Politics. Archived from the original on September 25, 2013. Retrieved September 25, 2013.

- ^ Dean, James (April 15, 2014). "With nod to history, SpaceX gets launch pad 39A OK". Florida Today. Archived from the original on July 30, 2014. Retrieved September 16, 2014.

- ^ Sheetz, Michael (April 30, 2020). "NASA awards contracts to Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk to land astronauts on the moon". CNBC. Archived from the original on April 30, 2020. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ Christian, Davenport (April 30, 2020). "Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk win contracts for spacecraft to land NASA astronauts on the moon". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 10, 2020. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ Boyle, Alan (March 11, 2023). "NASA's economic impact report card for Washington state highlights Blue Origin". GeekWire. Archived from the original on March 31, 2023. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (December 7, 2022). "Blue Origin and Dynetics bidding on second Artemis lunar lander". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved April 3, 2023.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (July 18, 2014). "Bezos Investment in Blue Origin Exceeds $500M". Space News. Archived from the original on July 19, 2014. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- ^ St. Fleur, Nicholas (April 5, 2017). "Jeff Bezos Says He was Selling $1B a Year in Amazon Stock to Finance Race to Space". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 7, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2017.

- ^ "Rocket fire of the vanities: Bezos space trip brings criticism from Earth-bound philanthropists-The Boston Globe". BostonGlobe.com. Archived from the original on September 17, 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- ^ Erwin, Sandra (April 8, 2019). "Blue Origin urging Air Force to postpone launch competition". SpaceNews.com. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved October 19, 2019.

- ^ Hollinger, Peggy (July 3, 2023). "Blue Origin looks to expand beyond US with international launch site". Financial Times. Archived from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ^ "The Space Review: Architecting lunar infrastructure". www.thespacereview.com. Retrieved May 27, 2024.

- ^ Boyle, Alan. "Amazon.com billionaire's 5-ton flying jetpack lands in Seattle museum". NBC News. Archived from the original on February 3, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ "Blue Origin Charon Test Vehicle". The Museum of Flight. Archived from the original on March 24, 2013. Retrieved March 4, 2013.

- ^ "Blue Origin's Original Charon Flying Vehicle Goes on Display at The Museum of Flight". The Museum of Flight. Archived from the original on March 28, 2013. Retrieved March 4, 2013.

- ^ "Blue Origin Charon Test Vehicle". Museum of Flight. Archived from the original on March 24, 2013. Retrieved August 6, 2016.

- ^ Boyle, Alan (November 28, 2006). "Blue Origin Rocket Report". MSNBC. Archived from the original on April 15, 2008. Retrieved May 28, 2008.

- ^ Boyle, Alan (December 2, 2006). "Blue Alert For Blastoff". MSNBC. Archived from the original on May 7, 2008. Retrieved May 28, 2008.

- ^ "Launches". www.faa.gov. Archived from the original on April 21, 2019. Retrieved April 4, 2019.

- ^ "Blue Origin has a bad day (and so do some of the media)". Archived from the original on January 26, 2012. Retrieved September 3, 2011.

- ^ "Blue Origin Acknowledges Test Flight Failure". Space News. September 12, 2011. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2022.

- ^ "Blue Origin Engines". Blue Origin. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- ^ @jeff_foust (March 10, 2018). "Rob Meyerson shows this chart of the various engines Blue Origin has developed and the vehicle that have used, or will use, them. #spaceexploration" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Krebs, Gunter (April 29, 2018). "New Shepard". Gunter's Space Page. Archived from the original on May 16, 2018. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

External links

[edit]- Blue Origin

- 2000 establishments in Washington (state)

- Aerospace companies of the United States

- American companies established in 2000

- Collier Trophy recipients

- Companies based in Kent, Washington

- Culberson County, Texas

- Privately held companies based in Washington (state)

- Private spaceflight companies

- Space Act Agreement companies

- Space tourism

- Technology companies established in 2000

- Jeff Bezos