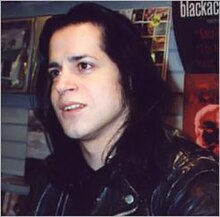

Glenn Danzig

Glenn Danzig | |

|---|---|

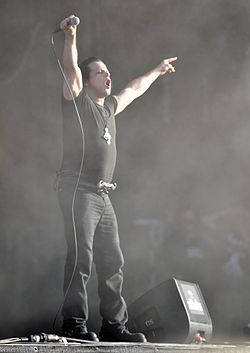

Danzig performing at Wacken Open Air 2018 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Glenn Allen Anzalone |

| Born | June 23, 1955 Lodi, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Occupations |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Years active | 1977–present |

| Labels |

|

| Member of | |

| Formerly of | Samhain |

| Website | danzig-verotik |

Glenn Allen Anzalone (born June 23, 1955),[1] better known by his stage name Glenn Danzig, is an American singer, songwriter, musician, and record producer. He is the founder of the rock bands Misfits, Samhain, and Danzig. He owns the Evilive record label as well as Verotik, an adult-oriented comic book publishing company.

Beginning in the mid-1970s, Danzig's musical career has encompassed a number of genres through the years, including punk rock and heavy metal, and incorporating influences from industrial, blues and classical music. He has also written songs for other musicians, most notably Johnny Cash and Roy Orbison.[2]

As a singer, Danzig is noted for his baritone voice and tenor vocal range; his style has been compared to those of Elvis Presley, Jim Morrison, and Howlin' Wolf.[3][4][5] Danzig has also cited Bill Medley as a vocal influence.[6] In 2023, Rolling Stone ranked Glenn Danzig at number 199 on its list of the 200 Greatest Singers of All Time.[7]

Early life

[edit]Danzig was born Glenn Allen Anzalone, the third of four sons,[8] in Lodi, New Jersey. His father was a television repairman and a United States Marine Corps veteran of World War II and the Korean War.[9] His mother worked at a record store.[10] Danzig and his family also spent some time living in Revere, Massachusetts.[11][12] Danzig began listening to heavy metal music at an early age, and has described Black Sabbath, the Ramones, Blue Cheer, and The Doors as being among his early musical influences.[6]

At age 10, Danzig began to use drugs and alcohol, leading him into frequent fights and trouble with the law.[13] He stopped using drugs at age 15.[13]

While growing up, Danzig began reading the works of authors including Charles Baudelaire and Edgar Allan Poe, developing his appreciation for horror.[14] Danzig collected comic books and, frustrated by American comics, he started his own company to produce "crazy, violent, erotic comics".[15]

Danzig graduated from Lodi High School in June 1973, aspiring to become a comic book creator[16] and professional photographer. He attended the Tisch School of the Arts and later the New York Institute of Photography.[17] Danzig formed an adult-oriented comic book company called Verotik in the mid-1990s.[18]

Musical career

[edit]Early career

[edit]Glenn Danzig's introduction to performing music began when he took piano and clarinet lessons as a child.[19] He later taught himself how to play the guitar.[19] Danzig started in the music business at the age of 11, first as a drum roadie[18] and then playing in local garage bands.[16] He had never taken vocal lessons, but his self-taught vocal prowess gained him attention in the local scene. Throughout his teenage years he sang for several local bands, such as Talus and Koo-Dot-N-Boo-Jang, most of which played half original songs and half Black Sabbath songs.[20]

Misfits and Samhain (1977–1987)

[edit]In the mid-1970s, Danzig started the Misfits, releasing the band's records through his own label (originally known as Blank, later as Plan 9).[21] Danzig had attempted to get the Misfits signed to several record labels, only to be told that he would never have a career in music.[22] The impetus for the band's name comes from Marilyn Monroe's last film,[23] combined with Danzig considering himself to be a "social misfit".[2] The band released several singles and two albums, spawning a cult following. Danzig disbanded the Misfits in October 1983 due to personal and professional differences.[2] He later explained, "It was difficult for me to work with those guys, because they weren't prepared to put in the hours practicing. I wanted to move things forward, and they didn't seem to have the same outlook."[23]

Before the disbanding of the Misfits, Danzig had begun working on a new band project, Samhain,[2] which began when he started rehearsing with Eerie Von (formerly of Rosemary's Babies).[24] Danzig took the name of the band from the ancient Celtic New Year (which influenced the evolution of the modern Halloween). Initially Samhain was conceived as a punk rock "super group". The band briefly featured members of Minor Threat and Reagan Youth, who contributed to Samhain's 1984 debut, Initium. The band then settled with a lineup consisting of Eerie Von on bass, Damien on guitar, and Steve Zing on drums (later replaced by London May). In 1985 the Unholy Passion EP was released, followed by November-Coming-Fire in 1986.

Samhain eventually attracted the interest of major labels including Epic and Elektra.[25] Rick Rubin, music producer and head of the Def American label, would see the band perform at the 1986 New Music Seminar, on the advice of then-Metallica bassist Cliff Burton.[25][26] Danzig has credited both Burton and Metallica frontman James Hetfield with helping to raise awareness about his music: "I first met them at a Black Flag gig, and then we became kinda friends. We'd often bump into each other on the road...James and Cliff helped to spread the word about me, and I was very grateful to them."[23]

Danzig

[edit]"Classic" era (1987–1994)

[edit]In 1987, after two albums and an EP, Samhain was signed to a major label by Rubin and the name of the band was changed to Danzig to allow the band to retain its name in the event of line-up changes.[17] Danzig discussed the reasoning behind the name change: "Rick [Rubin] convinced me it was the way to go, and would also provide me with a lot more artistic freedom. After all, I was now in charge of where we were going musically, so if I didn't want to do something, it was a lot easier to say so."[23]

Danzig's intention at the time was for each album he recorded to consist of a different recording line-up, allowing him to keep working with different musicians.[27] The original band consisted of guitarist John Christ, bassist Eerie Von, and former Circle Jerks–DOA–Black Flag drummer Chuck Biscuits.

In 1987, Danzig, owing to his association with Rubin, was asked to write a song for Roy Orbison. The result was "Life Fades Away", featured in the 1987 movie Less than Zero.[2] Danzig also contributed to the film's soundtrack with "You and Me (Less than Zero)".[2] Danzig had originally been asked to write the song for a female vocalist, but when Rubin could not find a suitable singer, Danzig recorded the vocals himself.[28] The song is credited to Glenn Danzig and the Power Fury Orchestra, which featured the same membership as the initial lineup of Danzig, with the exception of Eerie Von. Since Von did not like the way producer Rubin wanted the bass played on the song, George Drakoulias played the bass instead.

In 1988, the newly formed band Danzig released their eponymous debut. Its sound showed a progression from the gothic–deathrock sound of Samhain, to a slower, heavier, more blues-based heavy metal sound.

In 1990, the band's sophomore effort, Danzig II: Lucifuge, marked an immediate change in musical direction. The album's overall bluesier tone and somewhat milder approach were departures from Danzig, featuring a '50s-style ballad ("Blood & Tears") and a full-on acoustic blues ("I'm the One").

Other projects in 1990 included the final Samhain album, Final Descent. The album was started under the title Samhain Grim several years prior. The album contained previously unreleased studio recordings, at least some of which had been intended for the Samhain Grim album before it was aborted.

In 1992, Danzig again changed musical direction, releasing the darker Danzig III: How the Gods Kill. Several songs featured a more textured, slower sound between fast, dominant guitar riffs.

Also in 1992, Danzig tried his hand at composing classical music with Black Aria. The album debuted at number 1 on the Billboard classical music chart.[29]

In 1993, Danzig released Thrall-Demonsweatlive, an EP featuring both studio recordings and live tracks. Danzig broke into the mainstream when the live video of "Mother '93" became a hit on MTV and earned Buzz Bin rotation,[30] six years after the original song was recorded. During this time the band reached its commercial peak, with both the debut album and Thrall-Demonsweatlive being certified Gold, and "Mother" becoming the band's highest charting single. Both Danzig and Thrall-Demonsweatlive have since been certified Platinum.[31]

In 1994, the release of Danzig 4 saw the band going further into a darker and more experimental sound. The album also saw further development of his vocal style and range, most notable in songs like "Let It Be Captured", and a more blues-based approach on songs like "Going Down to Die".

Also in 1994, Danzig's song "Thirteen", written for Johnny Cash, appeared on the latter musician's album American Recordings.[2]

Later years (1995–2004)

[edit]

In 1996, the band underwent a complete overhaul. The original lineup had fallen apart, as had Glenn Danzig's relationship with their record label, American Recordings, with label owner Rick Rubin's involvement as producer diminishing with each album.[17] Danzig would later engage in a legal battle with Rubin over unpaid royalties and the rights to the band's unreleased songs.[19] Danzig enlisted new bandmates, most notably Joey Castillo, who would be the band's drummer until 2002.

Once again, he explored a new musical direction and recorded Blackacidevil, this time infusing heavy metal with industrial rock. Danzig went on to sign a deal with Hollywood Records, which led to several religious groups boycotting its parent company, Disney, for signing a controversial "satanic" band.[32][33] As a result, the label pulled support for Blackacidevil and the record deal was severed.[34]

In September 1999, Danzig signed his band to E-Magine Records, becoming the first artist on the label.[35] The deal also led to the release of a Samhain box set and the re-release of Blackacidevil.[35]

Danzig's subsequent three albums, 6:66 Satan's Child (1999), I Luciferi (2002) and Circle of Snakes (2004), all musically and lyrically evolved to a more stripped down, heavier gothic metal sound. The Danzig lineup continued to change with each album, while Danzig's voice started to show change after years of touring.

In 1999, during the U.S. touring for the album 6:66 Satan's Child Danzig reunited Samhain along with drummers Steve Zing and London May. Then-Danzig guitarist Todd Youth was invited by Glenn Danzig to fill in the guitar position for the Samhain reunion tour, replacing Samhain's original guitarist, Pete "Damien" Marshall, who had opted out in order to tour with Iggy Pop. Eerie Von was not invited to rejoin Samhain due to personal issues within the band. Both Zing and May handled bass duties, switching from drums to bass in between the "Blood Show".

In 2003, Danzig founded the Blackest of the Black tour to provide a platform for dark and extreme bands of his choosing from around the world.[36][37] Bands featured on the tour have included Dimmu Borgir, Superjoint Ritual, Nile, Opeth, Lacuna Coil, Behemoth, Skeletonwitch, Mortiis and Marduk.

Recent activity (2005–2011)

[edit]In 2005, Danzig's tours to support the Circle of Snakes album and the Blackest of the Black Tour were highlighted by the special guest appearance of Misfits guitarist Doyle Wolfgang von Frankenstein. Doyle joined Danzig on stage for a 20-minute set of classic Misfits songs: "To do this right, I invited Doyle to join Danzig on stage at 'Blackest of the Black' for a special guest set. This is the first time we will be performing on stage together in 20 years. It's the closest thing to a Misfits reunion anyone is ever going to see."[38]

On October 17, 2006, he released his second solo album, Black Aria II. The album reached the top ten on the Billboard classical music chart.[39]

In November 2006, Danzig toured the west coast with former Samhain drummer Steve Zing on bass. They played three Samhain songs including "All Murder All Guts All Fun". In Los Angeles and Las Vegas, Doyle joined the band onstage for the encore and played two Misfits songs, "Skulls" and "Astro Zombies".[40]

In 2007 Danzig produced the debut album by ex-Misfits guitarist Doyle's metal-influenced band, Gorgeous Frankenstein.[41]

In July 2007, Danzig released The Lost Tracks of Danzig, a compilation of previously unreleased songs. The project took nine months to complete with Glenn Danzig having to add extra vocal and instrument tracks to songs that had been unfinished.[42] The album included the controversial "White Devil Rise", recorded during the sessions for Danzig 4 in response to inflammatory comments by Louis Farrakhan and his use of the term "The White Devil".[43][44] The song is Danzig's conjecture as to what would happen if Farrakhan incited the passive white race to rise up and start a race war: "No one wants to see a race war. It would be terrible, so the song's saying, 'Be careful what you wish for.'"[44][45] Danzig himself has bluntly denied any accusations of racism: "As far as me being an Aryan or a racist, anyone who knows me knows that's bullshit."[17]

In October and November 2007, Danzig toured the western United States, along with Gorgeous Frankenstein, Horrorpops, and Suicide City. This "3 Weeks of Halloween" tour was in support of his most recent album, The Lost Tracks of Danzig, as well as the newest graphic novel release from Verotik, Drukija: Countessa of Blood.[46] On October 23, 2007, Danzig was performing the song "How the Gods Kill" in Baltimore and fell off the stage, injuring his left arm. He did not perform the Misfits set that night,[46] but he continued the tour and played classic Misfits tunes with Doyle onstage as an encore with a sling on his left arm after the injury.

In 2008, Danzig confirmed he had recorded the first duet of his career, with Melissa Auf der Maur.[47] The song, titled "Father's Grave", features Danzig singing from the perspective of a gravedigger and appears on Auf der Maur's 2010 album Out of Our Minds.[48] Auf der Maur has spoken highly about the experience of meeting and working with Danzig.[48]

Danzig's ninth album, Deth Red Sabaoth, was released on June 22, 2010.[49]

In a July 2010 interview with Metal Injection, Glenn Danzig was asked if he was going to make another Danzig record after Deth Red Sabaoth. His response was, "I don't know, we'll see. With the way record sales are now...I won't do some stupid pro-tool record in someone's living room where all the drum beats are stolen from somebody and just mashed together...and I'm not going to do that if I can't do a record how I want to do it, and if it's not financially feasible, I'm just not going to do one."[50]

During the later quarter of 2011 Danzig performed a string of one-off reunion shows called the "Danzig Legacy" tour. The shows consisted of a Danzig set, followed by a Samhain set, then closing off with Danzig and Doyle performing Misfits songs.[51]

During the third date of Metallica's 30-year anniversary shows at the Fillmore Theater in San Francisco, Danzig went on stage with Metallica to perform the Misfits songs "Die, Die My Darling", "Last Caress", and "Green Hell".[52]

Current activity (2012–present)

[edit]

Danzig has said he wishes to avoid extensive and exhaustive touring in the future, preferring instead to focus on his various music, film and comic book projects: "I don't really want to tour. My reason for not doing it is because I'm bored of it. I like being onstage, but I don't like sitting around all day doing nothing. I could be home, working."[19][53] Danzig has started work on a third Black Aria album,[54] and a covers album is set for release by the end of 2013.[14] Danzig hopes to record a dark blues album involving Jerry Cantrell and Hank III.[19][55] He is currently working on new Danzig material with Tommy Victor and Johnny Kelly.[56][57][58]

In 2014, Danzig filed a lawsuit against Misfits bassist Jerry Only claiming Only registered trademarks for everything Misfits-related in 2000 behind Danzig's back, misappropriating exclusive ownership over the trademarks for himself, including the band's iconic "Fiend Skull" logo, violating a 1994 contract the two had. Danzig claims that after registering the trademarks, Only secretly entered into deals with various merchandisers and cut him out of any potential profits in the process.[59] On August 6, 2014, a U.S. district judge in California dismissed Danzig's lawsuit.[60]

On October 21, 2015, during an interview with Loudwire, Danzig stated his current tour with Superjoint could be his last.[61]

On May 12, 2016, Danzig, Only, and Frankenstein announced they would perform together as the Misfits for the first time in 33 years in two headlining shows at the September 2016 Riot Fest in Chicago and Denver.[62] He later noted that he would be "open to possibly doing some more shows". The reunited Misfits did more shows and Danzig enforced a "no cell phone" policy at the reunion shows.[63] The reunited "Original Misfits" sold out a succession of arenas, a singular accomplishment for a classic punk band, providing evidence that they are among the most popular punk bands ever.[64]

Danzig returned to Riot Fest in 2017 with his band Danzig. Their album Black Laden Crown was released on May 26, 2017.

Musical style

[edit]Danzig's musical career has encompassed a number of genres, from punk rock and heavy metal to classical music. He is noted for his baritone voice and tenor vocal range; his style has been compared to those of Elvis Presley, Jim Morrison, Roy Orbison and Howlin' Wolf. Critic Mark Deming of Allmusic described Danzig as "one of the very best singers to emerge from hardcore punk, though in a genre where an angry, sneering bark was the order of the day, that only says so much. Still, the guy could carry a tune far better than his peers".[65] As a musician, in addition to his vocals, Glenn Danzig has also contributed guitar, bass, drums and piano to his various musical projects.

The Misfits combined Danzig's harmonic vocals with camp-horror imagery and lyrics. The Misfits sound was a faster, heavier derivation of Ramones-style punk with rockabilly influences. Glenn Danzig's Misfits songs dealt almost exclusively with themes derived from B-grade horror and science fiction movies (e.g. "Night of the Living Dead") as well as comic books (e.g. "Wasp Women", "I Turned into a Martian").[2] Unlike the later incarnation of the Misfits, Danzig also dealt with Atomic Era scandals in songs like "Bullet" (about the assassination of John F. Kennedy), "Who Killed Marilyn" (which alluded to alternate theories about Marilyn Monroe's death), and "Hollywood Babylon" (inspired by the Kenneth Anger book on scandals associated with the early, formative years of Hollywood). In later years the Misfits style was noticeably heavier and faster than during their earlier releases, introducing elements of hardcore punk.

Samhain's musical and lyrical style was much darker in tone than Misfits material,[2] fusing an experimental combination of horror punk, gothic–death rock, and heavy metal. With Samhain, Glenn Danzig began to introduce more complicated drum patterns. Samhain songs often combined tribal drum beats and distorted guitars. Samhain's lyrical themes were rooted in paganism and the occult, pain and violence, and the horrors of reality.

The band Danzig showed a progression to a slower, heavier, more blues-based and doom-driven heavy metal sound primarily influenced by the early sound of Black Sabbath.[66] Other musical influences include The Doors,[67] and the ballads of Roy Orbison.[68][69] Danzig opted for a thicker and heavier-sounding guitar tone than with his previous bands, retaining his preference for a single lead guitarist and short guitar solos. After replacing the band's original line-up, Danzig began to experiment with a more industrial sound, before merging into gothic metal. Later, Danzig albums have returned to the band's original sound.

Glenn Danzig's lyrics, which had already evolved from those of the Misfits to the more serious style of Samhain, progressed even further with Danzig to become "frighteningly intense images of doom" which "convey their bleak messages with an eerie grace and intelligence".[6] His lyrics are typically dark in subject matter, bearing "a heavily romanticized, brooding, gothic sensibility, more quietly sinister and darkly seductive than obviously threatening or satanic".[70] Lyrical themes include love, sex, evil, death, religion, and occult imagery. Danzig's songs about love often deal with the pain of loss and loneliness using gothic romanticism.[71][72] Sex is another common theme, with songs frequently alluding to various sexual practices and depicting powerful, seductive and sometimes supernatural female figures. Glenn Danzig has tackled Biblical subjects and has offered his criticisms of organised religion.[73] He often promotes rebellion and anti-authoritarianism, whilst embracing independence and the left-hand path. In other lyrics, Danzig deals with the subject of death and questions the concepts of evil and sin.[74]

Glenn Danzig has served as the sole songwriter for every band he has fronted, and described his writing process: "Sometimes I get the guitar lines, sometimes I write on the piano, sometimes I'll write the lyrics first and then figure out the chord patterns on guitar, and sometimes I write the drum pattern first. It's all different".[75] Danzig also records basic song ideas when away from his home: "I usually hum it into a microcassette recorder and then I transpose it when I get home and work it out on guitar or piano".[75]

Television and film

[edit]Danzig had a minor role as a fallen angel in the 1998 film The Prophecy II, starring Christopher Walken.[76]

He was invited by 20th Century Fox to audition for the role of Wolverine in X-Men,[77] as his height and build closely resemble that of the film's protagonist, as described in the original comic books.[78] However, he declined due to scheduling conflicts.[78] He later admitted that he was glad to turn the role down as he thought the final product was "terrible" and further insulted Hugh Jackman's performance, calling it "gay".[79]

Danzig guest-appeared as himself in the Aqua Teen Hunger Force episode "Cybernetic Ghost of Christmas Past from the Future",[80] where he purchased the house of the character Carl.

In February 2016, Danzig appeared in the Portlandia episode "Weirdo Beach".[81]

Directing

[edit]Danzig plays a personal role in the production of the band's music videos, suggesting ideas and sometimes directing them himself.[82] He has worked on a film version of the Verotik comic Ge Rouge.[13] The possibility of an animated film version of the Satanika comic has also been discussed.[83]

In 2019, Danzig made his feature film directorial debut with Verotika,[84] an anthology horror film that premiered at Chicago's Cinepocalypse Film Festival that year.[85][86][87][88] The film was directed, written and scored by Danzig.[85]

In September 2019, at the Los Angeles red carpet premiere of the Rob Zombie film 3 from Hell, Danzig told interviewers that production for a new film would begin in October. He described the project as "a vampire Spaghetti western", after revealing there would not be any more Misfits tours.[89]

In 2020, Danzig announced his next film was Death Rider in the House of Vampires, which blends elements of the Spaghetti western with vampire horror. Danzig stated there would be several prominent actors in the film, including: Devon Sawa, Danny Trejo, Julian Sands, and Kim Director.[90][91]

In multiple interviews, Danzig cites Italian horror director Mario Bava among his directorial inspirations, along with Sergio Leone and Jean Cocteau.[92]

Personal life

[edit]In January 1992, Danzig became a student of Jerry Poteet, a martial artist in Jeet Kune Do.[28][93] Danzig has since earned a teaching degree in the discipline.[28] Danzig has also studied Muay Thai.[28]

Danzig, who is 5 ft 3 in height,[94] also developed an interest in bodybuilding:

- I've always been attracted to the Nietzschean idea of perfection, and so I began trying to perfect my body. I bought Arnold Schwarzenegger's ENCYCLOPEDIA OF MODERN BODYBUILDING and started studying. Lifting weights is just lifting weights, but bodybuilding is about sculpting the body. Nutrition is essential, and though I'd like to be eating candy and cake, it immediately settles on my hips. Unfortunately, when I'm on the road I only get to work out a few times weekly, but when I'm at home with my weights and machines I work out four or five times a week.[95]

Danzig has several distinctive tattoos, all by tattoo artist Rick Spellman, which incorporate artwork based upon his music.[96] These include a Danzig/Samhain skull symbol designed by Michael Golden,[97] a bat with a Misfits Crimson Ghost skull, a wolf's head with the text "Wolfs Blood" (the title of a Misfits song),[96] a skeleton as found on the cover art for the album November-Coming-Fire, and a demon woman as found on the cover art for Unholy Passion. His lower back features the logo for the Devilman manga.

Danzig is a fan of horror movies and Japanese anime/manga, and has expressed his appreciation for the works of filmmaker David Cronenberg and manga artist Go Nagai.[98][99]

Danzig's favorite composers include Richard Wagner, Sergei Prokofiev, Camille Saint-Saëns, Carl Orff, and film score composer Jerry Goldsmith.[100]

Danzig is an avid reader and owns a large book collection on subjects including the occult, religious history and true murder cases.[6][101][102] He commented about the book The Occult Roots of Nazism that "every school kid should have this book", though he later stated that the comment was satirical.[103][104] Danzig also has a long-standing interest in New World Order-related conspiracies: "Not only have I always been interested in the families that run the world forever, that people know now as the Bilderberg Group. But there's an older book called Committee of 300 which tells you all about it. I mean, I got in trouble for this back in the 90s, talking about this kind of stuff – how the United States is based on a Freemason thing, and I got so many government files on me from that one".[105]

Regarding his political views, Danzig has described himself as being "conservative on some issues, and some issues I'm really liberal". He defended former President Donald Trump's controversial travel ban from selected countries, arguing "It's really not a travel ban. When you walk into the country, we want to see who you are and what you're doing."[106] Danzig has voiced his dissatisfaction with the United States' two-party system; stating "the bottom line is that both parties are in agreement about one thing: They don't want a third, a fourth, or a fifth party in there. They want it Democratic and Republican. Both sides are corrupt."[107]

Though sometimes portrayed as a Satanist by the media, Danzig has denied this in several interviews, elaborating that "I embrace both my light and dark side ... I definitely believe in a yin and yang, good and evil. My religion is a patchwork of whatever is real to me. If I can draw the strength to get through the day from something, that's religion ... I'm not trying to be preachy or tell people what to think."[8][17][108][109] Danzig has voiced his approval of certain aspects of Satanic ideologies, including the quest for knowledge and individual freedom.[108][110] He has stated that religion does not play a role in how he perceives other bands and musicians.[109]

Discography

[edit]

Danzig[edit]Studio albums

EPs

Singles

Compilations

Live albums

Soundtracks

Official videography

|

Misfits[edit]Studio albums

EPs

Singles

Compilations

Live albums

Soundtracks

Samhain[edit]Studio albums

Other releases

Glenn Danzig and the Power Fury Orchestra[edit]

Solo[edit]Studio albums

Singles

Other[edit]

|

References

[edit]- ^ Gregory, Andy (2002). International Who's Who in Popular Music 2002 (4th ed.). Europa Publications. p. 123. ISBN 978-1-85743-161-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Cipollini, Christian. "Glenn Danzig – Horror Business". Penny Blood. Archived from the original on August 21, 2008. Retrieved December 28, 2013.

- ^ Craig Lee. "Horror-movie rock from Misfits". L.A. Times. April 15, 1982

- ^ Mike Gitter. "Live Metal". RIP Magazine. 1988

- ^ Mike G. "Interview with Danzig". Metal Maniacs. December 1999.

- ^ a b c d Zogbi, Mariana (Spring 1989). "Danzig on Thin Ice". Metal Mania. Archived from the original on September 26, 2010. Retrieved October 28, 2009.

- ^ "The 200 Greatest Singers of All Time". Rolling Stone. January 1, 2023. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ a b Young, Jon (August 1994). "Danzig Knows the Power of the Dark Side". Musician. Archived from the original on December 20, 2010. Retrieved February 8, 2011.

- ^ Burk, Greg (October 27, 1999). "Glenn Danzig interview, 1999". LA Weekly. Archived from the original on November 27, 2010. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- ^ Kitts, Jeff (September 1994). "The Dark Knight Returns". Flux Magazine. Archived from the original on December 20, 2010. Retrieved April 20, 2011.

- ^ Lyford, Joshua (October 1, 2015). "Danzig brings the rock to Rock and Shock - Worcester Mag". worcestermag.com. Archived from the original on May 7, 2018. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- ^ Eakin, Marah (February 11, 2016). "Other than Portlandia, Glenn Danzig doesn't get to the beach very often". avclub.com. Archived from the original on May 7, 2018. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- ^ a b c Schieppati, Brandan (December 2006). "Rebel Meets Rebel". Revolver. Archived from the original on July 14, 2010. Retrieved January 16, 2010.

- ^ a b Moorman, Trent (August 21, 2013). "Glenn Danzig is a Macabre American Hero". The Stranger. Archived from the original on August 25, 2013. Retrieved September 4, 2013.

- ^ Samira Alinto. "Interview: Glenn Danzig – one of the last divas – STALKER MAGAZINE inside out of rock´n´roll". Stalker.cd. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ^ a b Engleheart, Murray (February 1994). "DANZIG Demons Down Under". RIP. Archived from the original on September 26, 2010. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Blush, Steven (October 1997). "Glenn Danzig". Seconds. Archived from the original on September 26, 2010. Retrieved October 3, 2009.

- ^ a b "Sympathy for the Devil". Entertainment Weekly. October 14, 1994. Archived from the original on June 13, 2011. Retrieved August 3, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Lee, Cosmo (October 9, 2009) [2007]. "Interview: Glenn Danzig". Invisible Oranges. Archived from the original on March 27, 2010. Retrieved March 31, 2010.

- ^ Smith, George (August 18, 1990). "On Tour, Gothic Metal Band Danzig Usually Goes It Alone". The Morning Call. Archived from the original on April 18, 2023. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- ^ Nieradzik, Andrea (Spring 1989). "Moaning Misfit". Metal Hammer magazine. Archived from the original on September 26, 2010. Retrieved October 16, 2009.

- ^ Weingarten, Christopher R. (July 19, 2010). "eMusic Q&A: Danzig". eMusic. Archived from the original on July 16, 2010. Retrieved July 23, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Dome, Malcolm (2011). "The Story Behind...Danzig". Metal Hammer (May 2011). Future plc: 70–72.

- ^ "Interview with Eerie Von". Live4Metal. June 2008. Archived from the original on February 12, 2009. Retrieved August 27, 2010.

- ^ a b Yates, Amy Beth (April–May 1989). "Danzig Dark Arts". B Side. Archived from the original on September 26, 2010. Retrieved October 23, 2009.

- ^ Wild, David (March 24, 1994). "The Devil Inside". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on September 25, 2010. Retrieved August 6, 2010.

- ^ Ferris, D.X. (May 24, 2007). "Danzig's Lost and Found: Underground Auteur Unearths Hits from Hell". OC Weekly. Archived from the original on July 11, 2010. Retrieved November 11, 2010.

- ^ a b c d "Glenn Danzig Satan's Child". the7thhouse.com. November 10, 1999. Archived from the original on July 5, 2008. Retrieved October 9, 2009.

- ^ "Glenn Danzig Unleashes 'Black Aria II' To Follow-Up His Classic Release". Metal Underground. August 30, 2006. Archived from the original on October 7, 2012. Retrieved December 16, 2009.

- ^ "On the Same Track". Entertainment Weekly. February 18, 1994. Archived from the original on April 21, 2009. Retrieved August 2, 2010.

- ^ Farr, Sara (August 2005). "DANZIG Interview". Unrated Magazine. Archived from the original on October 22, 2013. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ Philips, Chuck (October 15, 1996). "Disney to Release Album by Danzig". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 20, 2008. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ^ Boje, David (2000). "Phenomenal Complexity Theory and Change at Disney Vol 13(6): 558–566". Journal of Organizational Change Management. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ^ Stratton, Jeff (April 20, 2000). "The Devil Inside: Behold the Awesome Power of Danzig". Miami New Times. Archived from the original on November 2, 2012. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- ^ a b Siegler, Dylan (February 10, 2001). "E-magine's Strategy is Key to Its Success". Billboard. Archived from the original on December 22, 2007. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- ^ "Blackest of the Black History". Blackest of the Black. Archived from the original on September 24, 2009. Retrieved October 2, 2009.

- ^ Farr, Sara. "Danzig: Blackest of the Black". Unrated Magazine. Archived from the original on September 29, 2011. Retrieved October 2, 2009.

- ^ Jones, Sefany (September 3, 2004). "Danzig Announces 'Blackest of the Black' Tour Lineup". KNAC. Archived from the original on December 22, 2011. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- ^ "DANZIG – Signs with The End records". The Metal Den. April 1, 2010. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved April 16, 2010.

- ^ "Danzig / Lacuna Coil / the Haunted – live in Los Angeles". Punknews.org. December 5, 2006. Archived from the original on September 23, 2009. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ^ "Gorgeous Frankenstein". SputnikMusic.com. Retrieved October 9, 2009.

- ^ The Lost Tracks of Danzig liner notes

- ^ "Glenn Danzig Talks on New Album". UltimateGuitar.com. May 31, 2007. Archived from the original on April 17, 2010. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- ^ a b Chris Harris and Jon Wiederhorn (June 15, 2007). "Glenn Danzig Calls New LP 'A Pain in the Butt'". MTV.com. Archived from the original on April 2, 2010. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- ^ ""The Lost Tracks of Danzig" Details, Release Date Revealed". MetalUnderground.com. April 3, 2007. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- ^ a b "Glenn Danzig Falls Off Stage in Baltimore?". Metal Underground. October 24, 2007. Archived from the original on October 9, 2012. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- ^ "Exclusive Interview with Glenn Danzig for DANZIG 20th Anniversary". Danzig-Verotik.com. August 18, 2008. Archived from the original on August 31, 2009. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- ^ a b Bliss, Karen (February 15, 2010). "Melissa Auf der Maur Has 'a Thing' for Danzig – and Now He's on Her Album". Noisecreep. Archived from the original on February 17, 2010. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- ^ Sciaretto, Amy (March 31, 2010). "Danzig, 'Deth Red Sabaoth' – New Album Exclusive". Noisecreep. Archived from the original on April 3, 2010. Retrieved March 31, 2010.

- ^ "DANZIG Discusses His New Album, Deth Red Sabaoth". Metal Injection. July 14, 2010. Archived from the original on July 17, 2010. Retrieved July 16, 2010.

- ^ "Official Danzig Website". danzig-verotik.com. Archived from the original on November 3, 2015. Retrieved October 23, 2015.

- ^ "Rob Halford, Glenn Danzig, Jerry Cantrell Perform With Metallica At Third 30th Anniversary Show - Blabbermouth.net". BLABBERMOUTH.NET. Archived from the original on January 7, 2012. Retrieved October 23, 2015.

- ^ Slevin, Patrick (December 17, 2009). "Interview with Danzig: He's The One, He's The One". The Aquarian Weekly. Archived from the original on June 16, 2012. Retrieved March 31, 2010.

- ^ Small, Aaron (November 1, 2010). "Danzig: On Wings of Leather and Rage". Brave Words & Bloody Knuckles. Archived from the original on December 26, 2010. Retrieved February 8, 2011.

- ^ "Glenn Danzig Talks 20th Anniversary Tour, Future Plans". Ultimate-Guitar.com. August 22, 2008. Archived from the original on April 8, 2010. Retrieved March 31, 2010.

- ^ "Glenn Danzig Talks 25th Anniversary of Debut Danzig Album, Upcoming Covers Disc + More". Loudwire.com. April 23, 2013. Archived from the original on May 2, 2013. Retrieved May 1, 2013.

- ^ "Glenn Danzig Talks To Full Metal Jackie About 'Legacy' TV Special, Covers Record, New Music". Blabbermouth.net. April 28, 2013. Archived from the original on August 9, 2013. Retrieved May 1, 2013.

- ^ "Danzig Recording New Music". Blabbermouth.net. February 20, 2014. Archived from the original on March 2, 2014. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- ^ "GLENN DANZIG Sues MISFITS' JERRY ONLY Over HOT TOPIC Deal". Blabbermouth.net. May 7, 2014. Archived from the original on May 8, 2014. Retrieved May 7, 2014.

- ^ "Glenn Danzig Bitch Slapped By Judge: No Hot Topic Money For You!". re-tox.com. August 12, 2014. Archived from the original on August 17, 2014.

- ^ "Glenn Danzig: 'I Don't Think I'm Going to Tour Anymore'". Loudwire. October 22, 2015. Archived from the original on October 23, 2015. Retrieved October 23, 2015.

- ^ "Misfits' original lineup to reunite for Riot Fest". consequenceofsount.net. May 12, 2016. Archived from the original on May 13, 2016.

- ^ Grow, Kory (May 26, 2017). "Glenn Danzig on Dark New LP, Misfits, Why He Hates Recent Presidents". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on May 27, 2017. Retrieved May 28, 2017.

- ^ "How the Misfits Turned into an Arena Performing Phenomena". Forbes. Archived from the original on August 9, 2021. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ Deming, Mark (2020). Danzig Sings Elvis Archived May 7, 2020, at the Wayback Machine review, accessed April 28, 2020

- ^ Iwasaki, Scott. "DANZIG Scores Megapoints with Saltair Moshers". Deseret News. Archived from the original on October 23, 2013. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- ^ Reger, Rick (February 16, 1997). "Bending the Metal: Glenn Danzig Shifts Gears, and the Sparks Still Fly". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on November 7, 2013. Retrieved November 7, 2013.

- ^ Gitter, Mike (June 30, 1990). "Glenn Danzig: Brawn to be Wild". Kerrang!. Archived from the original on February 27, 2012. Retrieved November 7, 2013.

- ^ Kitts, Jeff (July 1994). "Prime Cuts: John Christ". Guitar School. Archived from the original on February 29, 2012. Retrieved November 7, 2013.

- ^ Huey, Steve. "Danzig – AllMusic Artist Biography". AllMusic. Archived from the original on August 29, 2014. Retrieved November 6, 2013.

- ^ "Glenn Danzig chat". Trans World Entertainment. January 27, 2000. Archived from the original on April 19, 2012. Retrieved November 6, 2013.

- ^ Hicks, Robert (December 22, 2006). "Danzig brings metal and mythology to Sayreville show". Daily Record. Morristown. Archived from the original on July 10, 2013. Retrieved November 6, 2013.

the band redefined its identity with a combination of heavy metal and goth romanticism

(subscription required) - ^ Russell, Tom (September 3, 1992). "Glenn Danzig Interview". 102.5 Clyde 1. Archived from the original on February 27, 2012. Retrieved November 6, 2013.

- ^ Palmer, Robert (November 4, 1990). "POP VIEW; Dark Metal: Not Just Smash And Thrash". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 16, 2015. Retrieved November 6, 2013.

- ^ a b McPheeters, Sam. "Glenn Danzig". Vice. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved September 22, 2013.

- ^ Jensen, K. Thor (July 19, 2017). "11 Musicians We'd Actually Like To See On Game Of Thrones". Geek.com. Archived from the original on April 7, 2020. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ^ Graff, Gary (May 3, 1995). "Danzig with the devil: Rocker relishes his turn as music's bad boy". Knight-Ridder/Tribune News Services. Archived from the original on November 7, 2021. Retrieved January 28, 2010.

- ^ a b Nadel, Nick (April 28, 2009). "Five Fun Facts about Wolverine You Won't Learn from His Movie". AMC Networks. Archived from the original on November 2, 2012. Retrieved August 1, 2015.

- ^ "Danzig accuses Hugh Jackman of playing Wolverine gay". News.com.au. May 28, 2012. Archived from the original on April 30, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- ^ Schoof, Dustin (August 9, 2013). "Glenn Danzig Looks Back on 25 Years of Taking It to the People Ahead of Bethlehem Performance". The Express-Times. Archived from the original on September 8, 2013. Retrieved September 4, 2013.

- ^ Titus, Christa (February 8, 2016). "Glenn Danzig Dishes About His Upcoming 'Portlandia' Cameo and New Music on the Way". Billboard. Archived from the original on February 11, 2016. Retrieved February 13, 2016.

- ^ Sherman, Lee (June 1991). "Lucifuge video feature". Faces magazine. Archived from the original on September 26, 2010. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- ^ "Glenn Danzig: The Interview". Shakefire.com. October 18, 2010. Archived from the original on May 17, 2013. Retrieved February 8, 2011.

- ^ Boucher, Geoff (June 21, 2019). "'Verotika': Glenn Danzig's Directorial Debut Set for Halloween VOD Roll-Out". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on September 14, 2019. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- ^ a b Bromley, Patrick (March 10, 2020). "[Review] Glenn Danzig's 'Verotika' is the Horror Equivalent of 'The Room'". Bloody Disgusting. Archived from the original on May 11, 2020. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ^ McLevy, Alex (June 13, 2019). "Holy hell, Glenn Danzig might've just made The Room of horror anthologies". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on April 1, 2020. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ^ Allen, Nick (June 14, 2019). "Glenn Danzig Accidentally Made the Year's Best Horror-Comedy". Vulture. Archived from the original on April 4, 2020. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ^ McLevy, Alex; Colburn, Randall (June 24, 2019). "The best, worst, and weirdest of this year's Cinepocalypse film festival". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on April 7, 2020. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ^ Trapp, Philip (September 19, 2019). "Glenn Danzig to Start Shooting 'Vampire Spaghetti Western' Movie". Loudwire. Archived from the original on October 2, 2019. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- ^ "Glenn Danzig's Vampire Spaghetti Western 'Death Rider in the House of Vampires': More Details Revealed". Blabbermouth. January 3, 2020. Archived from the original on February 3, 2021.

- ^ Death Rider in the House of Vampires at IMDb

- ^ Fuentes, Danny (November 1, 2018). "Glenn Danzig Reflects on a Milestone of Cultural Menace". LA Weekly. Archived from the original on October 3, 2019. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- ^ "Glenn Danzig trained in Jeet Kune Do by Bruce Lee". YouTube. 1992. Archived from the original on May 13, 2013. Retrieved August 23, 2007.

- ^ Musicians 5'5" And Under Craig Hlavaty, Houston Press (October 29, 2010)

- ^ "ROCK SOLID - Glenn Danzig pumps up his volume". Archived from the original on January 28, 2022. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ a b "Danzig". Prick Magazine. USA. October 2005. Archived from the original on October 23, 2009. Retrieved October 6, 2009.

- ^ Comic Book Legends Uncovered Archived August 18, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Glenn Danzig Interview". Tales from the Crypt. Spring 1982. Archived from the original on September 27, 2010. Retrieved October 28, 2009.

- ^ "Glenn Danzig Interview". Hollywood Book & Poster. April 1989. Archived from the original on September 26, 2010. Retrieved October 28, 2009.

- ^ Flaherty, Michael (October 25, 2007). "60 Seconds with...Glenn Danzig". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 21, 2013. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ Heller, Jason. "Deeper into Music With Glenn Danzig | Music". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on December 18, 2008. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ^ "Danzig Home Video". Def American. 1990. Archived from the original on February 14, 2010. Retrieved October 28, 2009.

- ^ "Watch a Shirtless Glenn Danzig Give a Tour of His Creepy Bookshelf". flavorwire.com. October 29, 2012. Archived from the original on February 4, 2018. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- ^ Wild, David (March 24, 1994). "The Devil Inside Glenn Danzig". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- ^ Brockman, Daniel (June 21, 2010). "Interview: Glenn Danzig". The Phoenix. Archived from the original on October 21, 2013. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ "Misfits' Danzig defends Trump's Muslim travel ban - NME". nme.com. May 30, 2017. Archived from the original on February 4, 2018. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- ^ "Danzig: Blackest of the Black - Interview with Glenn Danzig". UnRated Magazine. Archived from the original on February 12, 2018. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- ^ a b Harward, Randy (September 2002). "Interview: Danzig". In Music We Trust. Archived from the original on February 9, 2010. Retrieved October 28, 2009.

- ^ a b Sean Cannon. "DANZIG WATCH 2010: In Which I Talk to Danzig Himself". buzzgrinder.com. Archived from the original on October 31, 2010. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ Burk, Greg (July 2007). "The Spin Interview: Glenn Danzig". Spin Magazine. Archived from the original on August 25, 2010. Retrieved October 28, 2009.

- ^ a b "Official DANZIG Fansite". The7thHouse.com. Archived from the original on August 31, 2009. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Glenn Danzig at AllMusic

- Glenn Danzig at IMDb

- Glenn Danzig audio interview from Synthesis magazine Archived February 6, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- 1955 births

- American cartoonists

- American crooners

- American heavy metal singers

- American Jeet Kune Do practitioners

- American male singer-songwriters

- American baritones

- American people of Scottish descent

- American people of German descent

- American people of Italian descent

- American punk rock singers

- Danzig (band) members

- Horror punk musicians

- Living people

- Misfits (band) members

- People from Lodi, New Jersey

- People from Revere, Massachusetts

- Samhain (band) members

- Singer-songwriters from New Jersey

- Tisch School of the Arts alumni