Bishopsgate Institute

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2011) |

The façade of the Institute by Charles Harrison Townsend (1895) | |

| Established | 1895 |

|---|---|

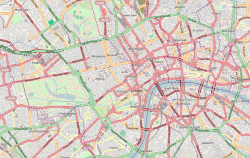

| Location | Bishopsgate London, EC2 United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 51°31′7.28″N 0°4′45.54″W / 51.5186889°N 0.0793167°W |

| Public transit access | |

| Website | www.bishopsgate.org.uk |

Bishopsgate Institute is a cultural institute in the Bishopsgate area of the City of London, located in the East End of London near Spitalfields and Shoreditch. The institute was established in 1895. It offers a cultural events programme, courses for adults, historic library and archive collections and community programme.

History

[edit]The Grade II* listed building was the first of the three major buildings designed by architect Charles Harrison Townsend (1851–1928).[1] The other two are the nearby Whitechapel Gallery and the Horniman Museum in south London.[2] His work combined elements of the Arts and Crafts movement and Modern Style (British Art Nouveau style), along with the typically Victorian.

Since opening on New Year's Day 1895, the Bishopsgate Institute has been a centre for culture and learning.

The original aims of the institute were to provide a public library, public hall and meeting rooms for people living and working in the City of London. The Great Hall, in particular, was erected for the benefit of the public to promote lectures, exhibitions and otherwise the advancement literature, science and the fine arts.

The Bishopsgate Institute was built using funds from charitable endowments made to the parish of St Botolph-without-Bishopsgate. These had been collected by the parish for over a period of 500 years, but a scheme agreed by the Charity Commissioners in 1891 enabled these to be drawn together into one endowment. Reverend William Rogers (1819–1896), rector of St Botolph's and a notable educational reformer and supporter of free libraries, was instrumental in setting up the institute and ensuring that the original charitable aims were met.

Bishopsgate Library

[edit]

Bishopsgate Library is a free, independent library, open every weekday and late night on Wednesdays.

The Special Collections and Archives beneath the library hold important historical collections about London, the labour movement, free thought and co-operative movements, as well as the history of protest and campaigning.[3]

There are over 250,000 images in the collections – including the London & Middlesex Archaeological Society (LAMAS) Glass Slide Collection, the London Co-operative Society and the London Collection Digital Photographs – as well as ephemera, papers, publications and letters. They have shared some of their images from LAMAS in 1977 on Historypin. This collection contains images of many of London's famous landmarks, including churches, statues, open spaces and buildings, as well as images showing social and cultural scenes from the early 20th century.[4]

Its librarian between 1897 and 1941 was Charles Goss, who argued against the trend to create open access libraries and innovated descriptive cataloguing to improve closed access discovery. His papers are held at the institute's archive.[5][6] He established their special collections in London history, labour history, free-thought and humanism.[7]

The library hosts the Great Diary Project, founded by Dr Irving Finkel, which by 2020 had collected more than 9,000 unpublished diaries.[8][9]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Our Architecture". Bishopsgate Institute. Bishopsgate Institute. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- ^ "Charles Harrison Townsend". Oxford Reference. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ "Special Collections & Archive". Bishopsgate Institute. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- ^ "Bishopgate Institute". Historypin. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011.

- ^ "Goss, Charles". Bishopsgate Institute Archive. Bishopsgate Institute. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- ^ Harris, C. W. J. (1970). "Charles Goss (1864–1946): Portrait of a Reactionary". Library World.

- ^ "Special collections in the heart of the city: Bishopsgate Library". Copac. Jisc. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- ^ Grant, Katie (7 May 2014). "The Great Diary Project: The survival of the permanent life archive". The Independent. London. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ^ "Great Diary Project". Retrieved 30 August 2020.