Big Sandy crayfish

| Big Sandy crayfish | |

|---|---|

| |

| A Big Sandy crayfish walking on a riverbed | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Malacostraca |

| Order: | Decapoda |

| Suborder: | Pleocyemata |

| Family: | Cambaridae |

| Genus: | Cambarus |

| Species: | C. callainus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Cambarus callainus Thoma, Loughman & Fetzner, 2014

| |

The Big Sandy crayfish, Cambarus callainus, are freshwater crustaceans of the family Cambaridae. They are found in the streams and rivers of Appalachia in Virginia, West Virginia, and Kentucky, in what is known as the Big Sandy watershed.[4] Populations are often mistaken with Cambarus veteranus (Guyandotte crayfish), but morphological and genetic data suggest that these are separate taxa; however, both are protected under the Endangered Species Act.[5] There is very little information available on the Big Sandy crayfish because it is a relatively new species.

Description

[edit]The adult Big Sandy crayfish range from 3 to 4 inches (7.6 to 10.2 cm) in length. Like other crayfish, they have been referred to as "miniature lobsters" since they share similar appearance. The colors of Big Sandy crayfish shells range from olive brown to light green, and their cervical grooves are outlined in blue, aqua, or turquoise.[6] They also have red and blue accents around their eyes and legs.[4] Their walking legs range from light green to green-blue to green in color, and their claws are usually aqua, but sometimes are found in green-blue to blue.

The Big Sandy crayfish are distinct from other crayfish in that they have narrower, elongated rostrums, narrower and elongated claws, and a lack of a well-defined lateral impression at the base of their claws’ immovable finger. The cephalothorax (main body section) of Big Sandy crayfish is streamlined and has the ability to elongate. They also have two well-defined cervical spines.

Ecology

[edit]Diet

[edit]Big Sandy crayfish are opportunistic omnivores, as they eat both living and dead plants and animals available in their habitats. They act as an important link in the food chain of their ecosystem, as they eat a wide variety of decaying and living small organisms and are then eaten by predators including mammals, sport fish, reptiles, birds, and amphibians.

Habitat

[edit]The Big Sandy crayfish live in clean, medium-sized, f|resh-water streams/rivers which are needed for social, reproductive, and energetic needs. They are found in fast moving sections of the water with large boulders or rocks that act as a home for the crayfish.[4] Little to no pollution or sedimentation is also a requirement for a healthy crayfish habitat. Because of the necessity for this type of environment, the Big Sandy crayfish are only found in the Appalachian mountain region.[7]

The Big Sandy crayfish is regarded as a tertiary burrower.[3]: 20457–20458 Among crayfish, tertiary burrowers live in water bodies year-round and excavate in the bottom substrate.[8][verification needed][9]: 159–160 [10]

Range

[edit]Commonly found in the rivers and streams of the Appalachian regions of Kentucky, Virginia, and West Virginia, the Big Sandy crayfish was first found in portions of Dickenson County, Virginia's Big Sandy basin in 1937.[4] Concurrent surveys showed that the species lived in surrounding areas as well. The range of the species was originally much larger but has now been cut down to a smaller size due to a variety of factors, including industrial scale forestry and coal mining. The erosion and sedimentation associated with these activities degraded the streams in the region and made most of them unsuitable for the crayfishes. Scientific evidence indicates that the Big Sandy crayfish once occurred in streams throughout the upper Big Sandy River basin in Kentucky, Virginia, and West Virginia (for range map, see[11]).

Today, the Big Sandy crayfish is found in six isolated populations across Floyd and Pike counties, Kentucky; Buchanan, Dickenson, and Wise counties, Virginia; and McDowell and Mingo counties, West Virginia.[7] It's known to be from the Big Sandy River basin, which flows northward until it joins the Ohio River.

Historic and current population size

[edit]The Big Sandy crayfish are known to be in poor/stressful conditions. Their range has been reduced by more than 60%, and now are sparsely found in the upper Big Sandy watershed in southern West Virginia, southwestern Virginia, and eastern Kentucky. A 2014 study conducted in Kentucky and Virginia demonstrated that the species was threatened, data showed that the CPUE ("crayfish per hour of searching") was 1.9 and 3.83, respectively.[6] In 2016, the Big Sandy crayfish was recognized by the Endangered Species Act.[3]

Life history

[edit]Information about reproduction of the Big Sandy crayfish is largely unknown since it is a new species; however the following information is from when C. callainus was still known as C. veteranus. Following the C. veteranus information is general Cambarus crayfish information to provide more insight on crayfish reproduction (for evolutionary history, see[12]).

Big Sandy crayfish

[edit]The Big Sandy crayfish exhibits "2-3 years of growth with maturation in the third year. The first mating is in the "midsummer of their third or fourth year." "Egg-laying takes place in the late summer or fall, and the young are released in the spring. The following late spring/early summer is when molting of the young occurs." The crayfish live approximately 5–7 years and molt 6 times during their lifetime.[6]

General Cambarus crayfish

[edit]After the male and female mate, the female holds the eggs in her swimmerets for around four to six weeks until she lays them. The eggs hatch 2–20 weeks after they are laid.[13] A young crayfish emerges from the egg with all the same structure of an adult crayfish. Not every egg produces a young crayfish, as upwards of 60% of the eggs are deficient due to genetic problems. One to two weeks after it hatches, the young crayfish leaves its mother. A majority of the young crayfish are eaten due to their small size. The crayfish starts to shed its exoskeleton often and grows rapidly through a process called molting.[13] The crayfish reaches full adult size around 3–4 months after it hatches from the egg. It then tries to find a mate to restart the cycle. The lifespan of the crayfish is 3–8 years long.

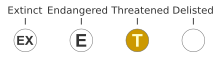

Conservation

[edit]In May 2016, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service listed the Big Sandy crayfish as a threatened species, protecting it under the Endangered Species Act.[4] However, some groups, such as the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature), the species under data deficient instead of threatened due to lack of history and research surrounding the animal. Under the Clean Water Act and the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act, the crayfish have been granted some protection from human influences. In 2019, the West Virginia Division of Highways and US Fish and Wildlife Service are working together to determine the effects of road activity on the crayfish.

Human impact on the species

[edit]In late 2019, the U.S. Fish Wildlife Service proposed to designate critical habitats for the Big Sandy crayfish and the Guyandotte crayfish. These habitats would be in the coalfields of Kentucky, Virginia, and West Virginia, and they would protect approximately 362 stream miles for the Big Sandy crayfish.[14][15]

According to a 2018 lawsuit brought by an environmental group, the Center for Biological Diversity, the species was being harmed by sediment from coal mining operations. They alleged that the U.S. Fish Wildlife Service was supposed to have designated a critical habitat in 2017.[16]

Major threats

[edit]There are several major threats to the Big Sandy crayfish. Pollution and high sediment values in the water supply can ruin a crayfish habitat. This usually occurs from mining, timbering, and the use of unpaved roads by off-road vehicles, causing high levels of erosion that go directly into the water streams and supplies often found at the bottom of valleys where the Big Sandy crayfish lives and thrives.[14] Additionally, other problems and threats to water quality include sewage discharges and chemical drainages from paved roads and surface mines which all can infect a water supply the crayfish are inhabiting. Fragmentation of habitats by man-made structures such as roads, dams, and reservoirs and watersheds cuts down the habitat space and the resources available.[4] Fragmentation additionally makes catastrophes, such as oil spills and large amounts of sedimentation in the water, increase in danger, because the crayfish cannot move anywhere else to escape these disasters and are directly exposed to the damages.

History of ESA and IUCN listings

[edit]The Big Sandy crayfish is listed as threatened wherever found under the ESA.[2] It was originally reviewed for listing in 1991 when it was known as C. veteranus. The crayfish was proposed to be listed as endangered with C. veteranus on 7 April 2015, which is when the two new species were distinguished in the ESA (ECOS 12 month finding).[6] The major threats for listing are small population size and habitat destruction, modification, or curtailment. The final rule was made on 7 April 2016: the Big Sandy crayfish was determined to be threatened,[3] not endangered, because more redundancy was determined, which increased resiliency. On 10 September 2018, a recovery plan outline was published for both species.[17]

The IUCN listed the Big Sandy crayfish as data deficient and last assessed it in 2010, when it was still known as C. veteranus.[18]

Current conservation efforts

[edit]Critical habitat designations were published simultaneously for the Big Sandy crayfish and Guyandotte crayfish in 2022,[19] following the 2020 publication of proposed critical habitat.[15] The Big Sandy crayfish has 362 stream miles (582 stream kilometers) designated as critical habitat, with streams in Kentucky, West Virginia and Virginia included. The critical habitat is divided into four units: the Upper Levisa Fork (entirely in Virginia), the Russell Fork (portions in Kentucky and Virginia), the Lower Levisa Fork (entirely in Kentucky) and the Tug Fork (portions in Kentucky, West Virginia and Virginia). The Tug Fork and Russell Fork units are similar in their total included stream length and together constitute the majority of the critical habitat.[19]: 14676–14677

A recovery outline for both the Big Sandy crayfish and the Guyandotte River crayfish was also published but has yet to be implemented. In this plan, the Big Sandy crayfish is listed as a priority 11C, with 1 being highest priority and 18 being lowest priority, due to a moderate degree of threat and low recovery potential. The recovery strategy has 4 main points:[17]

1. Research and monitoring

[edit]- Research to better understand species life history, habitat needs, and threats.

- Develop and implement captive holding, propagation, and reintroduction techniques

- Monitor listed crayfish populations and associated habitat conditions

- Conduct surveys in streams within species’ ranges to determine other suitable habitats/additional occupied habitats

2. Maintaining and enhancing resiliency of existing populations

[edit]- Protect habitat integrity and quality of streams within watersheds that currently support species

- Reduce potential for spills and develop spill response plan

- Protect and restore streams that support species

- Protect and restore riparian areas within crayfish watershed

3. Increasing redundancy by establishing connectivity between populations/creating additional populations

[edit]- Establish connectivity between existing populations and/or establish additional populations

4. Communication, outreach, and education

[edit]- Conduct outreach and education to increase understanding of and participation in crayfish conservation efforts

The long-term targets of this recovery plan include multiple viable populations well-distributed throughout range and threats (modification and degradation of habitat) abated. The short-term efforts of this plan include avoiding and/or minimizing disturbances and degradation in streams, investigating other potential causes for population decline, conducting research to fill in information gaps, developing "spill prevention and remedial action plans," and developing "captive holding/propagation techniques." Specific actions to avoid are any actions resulting in injury and/or death of the species, reduced reproduction of the species, increased stress on the species, or alteration of habitats to reduce survival or fitness of the species. Long-term efforts for this recovery plan include habitat restoration, population expansion, artificial propagation to prevent local extinction and buffer existing populations or create new populations, measures to "improve water quality and reduce sedimentation and containment input," and addressing other threats.[17]

References

[edit]- ^ "Cambarus callainus". NatureServe Explorer An online encyclopedia of life. 7.1. NatureServe. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- ^ a b "Big Sandy crayfish (Cambarus callainus)". Environmental Conservation Online System. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d USFWS. (7 April 2016) Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Threatened Species Status for the Big Sandy Crayfish and Endangered Species Status for the Guyandotte River Crayfish, Fed. Reg. 81(67): 20450–20481. Accessed 25 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f "Big Sandy crayfish". Southeast Region of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 25 March 2019. Archived from the original on 31 March 2021.

- ^ Longshaw, Matt; Stebbing, Paul, eds. (22 June 2016). Biology and Ecology of Crayfish. CRC Press. doi:10.1201/b20073. ISBN 978-0-429-08391-4.

- ^ a b c d USFWS. (7 April 2015) Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Endangered Species Status for the Big Sandy Crayfish and the Guyandotte River Crayfish, Fed. Reg. 80(66): 18710–18739. Accessed 25 April 2023.

- ^ a b "Northeast Region, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service". www.fws.gov. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ Hobbs, Jr., Horton H. (1942). "Crayfishes of Florida". University of Florida Publications, Biological Science Series. 3 (2): 1–279.

- ^ Hobbs, Jr., Horton H.; Hart, Jr., C.W. (1959). "The Freshwater Decapod Crustaceans of the Apalachicola Drainage System in Florida, Southern Alabama, and Georgia" (PDF). Bulletin of the Florida State Museum, Biological Sciences. 4 (5). Gainesville: University of Florida: 145–191. Retrieved 26 April 2023 – via Florida Museum.

- ^ Florey, Cassidy L. (May 2019). Description of Burrow Structure for Four Crayfish Species (Decapoda: Astacoidea: Cambaridae) (MSc). Bowling Green State University. Retrieved 26 April 2023 – via OhioLINK.

- ^ "Northeast Region, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service". www.fws.gov. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ^ Thoma, Roger F.; Loughman, Zachary J.; Fetzner, James Jr. W. (24 December 2014). "Cambarus (Puncticambarus) callainus, a new species of crayfish (Decapoda: Cambaridae) from the Big Sandy River basin in Kentucky, Virginia, and West Virginia, USA". Zootaxa. 3900 (4): 541–54. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3900.4.5. ISSN 1175-5334. PMID 25543755.

- ^ a b "Crayfish". www.psu.edu. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ a b "Federal agency would protect coalfields habitat for crayfish". www.whsv.com. Associated Press. 28 January 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ a b USFWS. (28 January 2020) Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Designation of Critical Habitat for the Big Sandy Crayfish and the Guyandotte River Crayfish Fed. Reg. 85(18): 5072–5122. Accessed 25 April 2023.

- ^ "Lawsuit Launched to Speed Habitat Protections for Two Appalachian Crayfish". www.biologicaldiversity.org. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ a b c Recovery Outline for the Guyandotte River Crayfish and Big Sandy Crayfish. US Fish and Wildlife Service. (10 September 2018) [Originally published May 2018]. Accessed 25 April 2023.

- ^ Cordeiro, J. & Thoma, R.F. (2020) [amended version of 2010 assessment]. "Cambarus veteranus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T3687A176118152. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T3687A176118152.en. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ a b 87 FR 14662