Montserrat

Montserrat | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "A people of excellence, moulded by nature, nurtured by God" | |

| Anthem: "God Save the King" | |

| National song: "Motherland" | |

Location of Montserrat (circled in red) | |

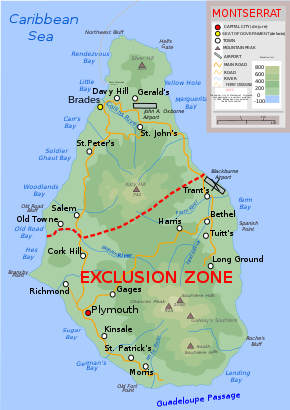

Topographic map of Montserrat showing the "exclusion zone" due to volcanic activity, and the new airport in the north. The roads and settlements in the exclusion zone have mostly been destroyed. | |

| Sovereign state | |

| English settlement | 1632 |

| Treaty of Paris | 3 September 1783 |

| Federation | 3 January 1958 |

| Separate colony | 31 May 1962 |

| Capital | Plymouth (de jure)[a] Brades (de facto)[b] Little Bay (under construction) 16°45′N 62°12′W / 16.750°N 62.200°W |

| Largest city | Brades |

| Official languages | English |

| Demonym(s) | Montserratian |

| Government | Parliamentary dependency under a constitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Charles III |

• Governor | Sarah Tucker[1] |

• Premier | Reuben Meade |

| Legislature | Legislative Assembly |

| Government of the United Kingdom | |

• Minister | Stephen Doughty |

| Area | |

• Total | 102 km2 (39 sq mi) |

• Water (%) | negligible |

| Highest elevation | 1,050 m (3,440 ft) |

| Population | |

• 2022 estimate | 4,390[2] (194th) |

• 2018 census | 4,649[3] (intercensal count) |

• Density | 46/km2 (119.1/sq mi) (not ranked) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2014 estimate |

• Total | US$63 million[4] |

• Per capita | US$12,384 |

| GDP (nominal) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | US$181,680,000[5] |

| Currency | East Caribbean dollar (XCD) |

| Time zone | UTC-4:00 (AST) |

| Driving side | left |

| ISO 3166 code | MS |

| Internet TLD | .ms |

| Website | https://www.gov.ms/ |

Montserrat (/ˌmɒntsəˈræt/ MONT-sə-RAT) is a British Overseas Territory in the Caribbean. It is part of the Leeward Islands, the northern portion of the Lesser Antilles chain of the West Indies. Montserrat is about 16 km (10 mi) long and 11 km (7 mi) wide, with roughly 40 km (25 mi) of coastline.[6] It is nicknamed "The Emerald Isle of the Caribbean" both for its resemblance to coastal Ireland and for the Irish ancestry of many of its inhabitants.[7][8] Montserrat is the only non-fully sovereign full member of the Caribbean Community and the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States, though it is far from being the only dependency in the Caribbean overall.

On 18 July 1995, the previously dormant Soufrière Hills volcano in the southern end of the island became active and its eruptions destroyed Plymouth, Montserrat's Georgian era capital city situated on the west coast. Between 1995 and 2000, two-thirds of the island's population was forced to flee, mostly to the United Kingdom, leaving fewer than 1,200 people on the island in 1997. (The population had increased to nearly 5,000 by 2016).[9][10] The volcanic activity continues, mostly affecting the vicinity of Plymouth, including its docks, and the eastern side of the island around the former W. H. Bramble Airport, the remnants of which were buried by flows from further volcanic activity on 11 February 2010.

An exclusion zone was imposed, encompassing the southern part of the island as far north as parts of the Belham Valley, because of the size of the existing volcanic dome and the resulting possibility of pyroclastic activity. Visitors are generally not permitted to enter the exclusion zone, but a view of destroyed Plymouth can be seen from the top of Garibaldi Hill in Isles Bay. The volcano has been relatively quiet since early 2010 and continues to be closely monitored by the Montserrat Volcano Observatory.[11][12]

In 2015, it was announced that planning would begin on a new town and port at Little Bay on the northwest coast of the island, and the centre of government and businesses was moved temporarily to Brades.[13] After a number of delays, including Hurricanes Irma and Maria in 2017[14] and the COVID-19 pandemic beginning in early 2020,[15] the Little Bay Port Development Project, a £28 million project funded by the UK and the Caribbean Development Bank, began in June 2022.

Etymology

[edit]In 1493, Christopher Columbus named the island Santa María de Montserrate, after the Virgin of Montserrat of the Monastery of Montserrat near Barcelona in Catalonia, Spain.[16] Montserrat means "serrated mountain" in Catalan.

History

[edit]

Pre-colonial era

[edit]Archaeological field work in 2012 in Montserrat's Centre Hills indicated that there had been an Archaic (pre-Arawak) occupation between 2000 and 500 BCE.[17] Later coastal sites showed the presence of the Saladoid culture (until 550 CE).[18] The native Caribs are believed to have called the island Alliouagana, meaning 'Land of the Prickly Bush'.[19]

In 2016, nine petroglyphs were discovered by local residents hiking in a wooded area near Soldier Ghaut.[20][21] Another was discovered in 2018 in the same area of the island.[21] The carvings are believed to be 1000–1500 years old.[20]

Early European period

[edit]In November 1493, Christopher Columbus passed Montserrat on his second voyage, after being told that the island was unoccupied because of raids by the Caribs.[22][19]

A number of Irishmen settled in Montserrat in 1632.[23] Most came from nearby Saint Kitts at the instigation of the island's governor Thomas Warner, with more settlers arriving later from Virginia.[19] The first settlers "appear to have been cultivators, each working his own little farm".[24]

The preponderance of Anglo-Irish in the first wave of European settlers led a leading legal scholar to remark that a "nice question" is whether the original settlers took with them the law of the Kingdom of Ireland insofar as it differed from the law of the Kingdom of England.[25]

The Irish being historical allies of the French, especially in their qualified disdain of the English, invited the French to claim the island in 1666, although no troops were sent by France to maintain control.[23] The French attacked and briefly occupied the island in the late 1660s;[26] it was captured shortly afterwards by the English, and English control of the island was confirmed under the Treaty of Breda the following year.[23] Despite the seizing by force of the island by the French, the island's legal status is that of a "colony acquired by settlement", as the French gave up their claim to the island at Breda.[23]

A neo-feudal colony developed amongst the so-called "redlegs".[27] The Anglo-Irish colonists began to transport both Sub-Saharan African slaves and Irish indentured servants for labour, as was common to most Caribbean islands. By the late 18th century, numerous plantations had been developed on the island.

18th century

[edit]There was a brief French attack on Montserrat in 1712.[26] On 17 March 1768, a slave rebellion failed but their efforts were remembered.[28][26] Slavery was abolished in 1834. In 1985, the people of Montserrat made St Patrick's Day a ten-day public holiday to commemorate the uprising.[29] Festivities celebrate the culture and history of Montserrat in song, dance, food and traditional costumes.[30]

In 1782, during the American Revolutionary War, as America's first ally, France captured Montserrat in their war of support of the Americans.[29][26] The French, not intending to colonise the island, agreed to return the island to Great Britain under the 1783 Treaty of Paris.[31]

New crops and politics

[edit]In 1834, Britain abolished slavery in Montserrat and its other territories.[32][29][26]

During the nineteenth century, falling sugar prices had an adverse effect on the island's economy, as Brazil and other nations competed in the trade.[33][34]

The first lime tree orchards on the island were planted in 1852 by a local planter, Mr Burke.[35] In 1857, the British philanthropist Joseph Sturge bought a sugar estate to prove that it was economically viable to employ paid labour rather than use slaves.[19] Numerous members of the Sturge family bought additional land. In 1869, the family established the Montserrat Company Limited and planted Key lime trees; started the commercial production of lime juice, with more than 100,000 gallons produced annually by 1895; set up a school; and sold parcels of land to the inhabitants of the island. The pure lime juice was transported in casks to England, where it was clarified and bottled by Evans, Sons & Co, of Liverpool, with a trade mark on each bottle intended to guarantee quality to the public.[24]

Much of Montserrat came to be owned by smallholders.[36][37]

From 1871 to 1958, the island was administered as part of the federal crown colony of the British Leeward Islands, becoming a province of the short-lived West Indies Federation from 1958 to 1962.[38][19] The first Chief Minister of Montserrat was William Henry Bramble of the Montserrat Labour Party from 1960 to 1970; he worked to promote labour rights and boost tourism to the island, and Montserrat's original airport was named in his honour.[39] Bramble's son, Percival Austin Bramble, was critical of the way tourist facilities were being constructed, and he set up his own party, the Progressive Democratic Party, which won the 1970 Montserratian general election. Percival Bramble served as Chief Minister from 1970 to 1978.[40] The period 1978 to 1991 was dominated politically by Chief Minister John Osborne and his People's Liberation Movement A brief flirtation with possibly declaring independence never materialised.

On 10 May 1991, the Caribbean Territories (Abolition of Death Penalty for Murder) Order 1991 came into force, formally abolishing the death penalty for murder on Montserrat.[41]

Corruption allegations within the PLM party resulted in the collapse of the Osborne government in 1991, with Reuben Meade becoming the new chief minister,[42] and early elections were called.[42]

In 1995–1999, Montserrat was devastated by catastrophic volcanic eruptions in the Soufrière Hills, which destroyed the capital city of Plymouth, and necessitated the evacuation of a large part of the island. Many Montserratians emigrated abroad, mainly to the United Kingdom, although some have returned. The eruptions rendered the entire southern half of the island uninhabitable, and it is currently designated an Exclusion Zone with restricted access.

Criticism of the Montserratian government's response to the disaster led to the resignation of Chief Minister Bertrand Osborne in 1997 after only a year in office. He was replaced by David Brandt, who remained in office until 2001. Since leaving office, Brandt has been the subject of multiple criminal investigation into alleged sex offences with minors.[43] He was found guilty of six counts of sexual exploitation and sentenced to fifteen years in July 2021.[44]

John Osborne returned as Chief Minister following victory in the 2001 election. He was ousted by Lowell Lewis of the Montserrat Democratic Party in 2006. Reuben Meade returned to office in 2009 to 2014.[45] During his term, the post of Chief Minister was replaced with that of Premier.

In the autumn of 2017, Montserrat was not affected by Hurricane Irma, and sustained only minor damage from Hurricane Maria.[46]

Since November 2019, Easton Taylor-Farrell of the Movement for Change and Prosperity party has been the island's Premier.

Politics and government

[edit]Montserrat is an internally self-governing overseas territory of the United Kingdom.[47] The United Nations Committee on Decolonization includes Montserrat on the United Nations list of non-self-governing territories. The island's head of state is King Charles III, represented by an appointed Governor. Executive power is exercised by the government, whereas the Premier is the head of government. The Premier is appointed by the Governor from among the members of the Legislative Assembly which consists of nine elected members. The leader of the party with a majority of seats is usually the one who is appointed.[6] Legislative power is vested in both the government and the Legislative Assembly. The Assembly also includes two ex officio members, the attorney general and financial secretary.[6]

The Judiciary is independent of the executive and the legislature.

Administrative divisions

[edit]

St. Peter (red)

St. Georges (green)

St. Anthony (cyan)

Plymouth (◾)

For the purposes of local government, Montserrat is divided into three parishes. Going north to south, they are:

- Parish of Saint Peter

- Parish of Saint Georges

- Parish of Saint Anthony

The locations of settlements on the island have been vastly changed since the volcanic activity began. Only the Parish of Saint Peter in the northwest of the island is now inhabited, with a population of between 4,000 and 6,000,[48][49] the other two parishes being still too dangerous to inhabit.

A significantly more up-to-date administrative division type would be the 3 census regions, primarily used for the population census.[50] Going north to south, these are:

- Northern Region (2,369 pop.)

- Central Region (1,666 pop.)

- South of Nantes river (887 pop.)

For census purposes, these are further divided into 23 enumeration districts.

Police

[edit]Policing is primarily the responsibility of the Royal Montserrat Police Service.

Military and defence

[edit]The defence of Montserrat is the responsibility of the United Kingdom. The Royal Navy maintains a ship on permanent station in the Caribbean (HMS Medway)[51] and from time-to-time may send another Royal Navy or Royal Fleet Auxiliary ship as a part of the Atlantic Patrol (NORTH) tasking. These ships' main mission in the region is to maintain British sovereignty for the overseas territories, provide humanitarian aid and disaster relief during disasters such as hurricanes, which are common in the area, and conduct counter-narcotics operations. In October 2023, the destroyer HMS Dauntless (which had temporarily replaced Medway on her Caribbean tasking), visited the territory in order to assist local authorities in preparing for the climax of the hurricane season.[52]

Royal Montserrat Defence Force

[edit]The Royal Montserrat Defence Force is the home defence unit of the British Overseas Territory of Montserrat. Raised in 1899, the unit is today a reduced force of about forty volunteer soldiers, primarily concerned with civil defence and ceremonial duties. The unit has a historical association with the Irish Guards.

Communications

[edit]The island is served by landline telephones, fully digitalised, with 3000 subscribers and by mobile cellular, with an estimated number of 5000 handsets in use. An estimated 2860 users have internet access. These are July 2016 estimates. Public radio service is provided by Radio Montserrat. There is a single television broadcaster, PTV.[53] Cable and satellite television service is available.[6]

The UK postcode for directing mail to Montserrat is MSR followed by four digits according to the destination town; for example, the postcode for Little Bay is MSR1120.[54]

Geography

[edit]

The island of Montserrat is located approximately 25 miles (40 km) southwest of Antigua, 13 miles (21 km) southeast of Redonda (a small island owned by Antigua and Barbuda), and 35 miles (56 km) northwest of the French overseas region of Guadeloupe. Beyond Redonda lies the island of Nevis (which is part of the federation of St Kitts and Nevis), about 30 miles (48 km) to the north-west.

Montserrat comprises 104 km2 (40 sq mi) and is gradually increasing owing to the buildup of volcanic deposits on the southeast coast. The island is 16 km (9.9 mi) long and 11 km (6.8 mi) wide and consists of a mountainous interior surrounded by a flatter littoral region, with rock cliffs rising 15 to 30 m (49 to 98 ft) above the sea and a number of smooth bottomed sandy beaches scattered among coves on the western (Caribbean Sea) side of the island.

The major mountains are (from north to south) Silver Hill, Katy Hill in the Centre Hills range, the Soufrière Hills and the South Soufrière Hills.[29] The Soufrière Hills volcano is the island's highest point; its pre-1995 height was 915 metres (3,002 ft). However, it has grown after the eruption due to the creation of a lava dome, with its current height being estimated at 1,050 metres (3,440 ft).[6]

The 2011 estimate by the CIA indicates that 30% of the island's land is classified as agricultural, 20% as arable, 25% as forest and the balance as "other".[6]

Montserrat has a few tiny off-shore islands, such as Little Redonda off its north coast and Pinnacle Rock and Statue Rock off its east.

Volcano and exclusion zone

[edit]

In July 1995, Montserrat's Soufrière Hills volcano, dormant for centuries, erupted and soon buried the island's capital, Plymouth, in more than 12 metres (39 ft) of mud, destroyed its airport and docking facilities, and rendered the southern part of the island, now termed the exclusion zone, uninhabitable and not safe for travel. The southern part of the island was evacuated and visits are severely restricted.[55] The exclusion zone also includes two sea areas adjacent to the land areas of most volcanic activity.[9]

After the destruction of Plymouth and disruption of the economy, more than half of the population left the island, which also lacked housing. During the late 1990s, additional eruptions occurred. On 25 June 1997, a pyroclastic flow travelled down Mosquito Ghaut. This pyroclastic surge could not be restrained by the ghaut (a steep revine leading to the sea) and spilled out of it, killing 19 people who were in the (officially evacuated) Streatham village area. Several others in the area suffered severe burns.

British nationality law has changed over time with respect to the status granted to Montserrat residents. In recognition of the disaster, in 1998, the people of Montserrat were granted full residency rights in the United Kingdom, allowing them to migrate if they chose. British citizenship was granted in 2002 to British Overseas Territories citizens in Montserrat and all but one other British Overseas Territory.[56]

For a number of years in the early 2000s, the volcano's activity consisted mostly of infrequent ventings of ash into the uninhabited areas in the south. The ash falls occasionally extended into the northern and western parts of the island. In the most recent period of increased activity at the Soufrière Hills volcano, from November 2009 through February 2010, ash vented and there was a vulcanian explosion that sent pyroclastic flows down several sides of the mountain. Travel into parts of the exclusion zone was occasionally allowed, though only by a licence from the Royal Montserrat Police Force.[57] Since 2014 the area has been split into multiple subzones with varying entry and use restrictions, based on volcanic activity: some areas even being (in 2020) open 24 hours and inhabited. The most dangerous zone, which includes the former capital, remains forbidden to casual visitors due to volcanic and other hazards, especially due to the lack of maintenance in destroyed areas. It is legal to visit this area when accompanied by a government-authorised guide.[58][59]

The northern part of Montserrat has largely been unaffected by volcanic activity, and remains lush and green. In February 2005, Princess Anne officially opened what is now called the John A. Osborne Airport in the north. Since 2011, it handles several flights daily operated by Fly Montserrat Airways. Docking facilities are in place at Little Bay, where the new capital town is being constructed; the new government centre is at Brades, a short distance away.

Wildlife

[edit]

Montserrat, like many isolated islands, is home to rare, endemic plant and animal species. Work undertaken by the Montserrat National Trust in collaboration with the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew has centred on the conservation of pribby (Rondeletia buxifolia) in the Centre Hills region. Until 2006, this species was known only from one book about the vegetation of Montserrat.[60] In 2006, conservationists also rescued several plants of the endangered Montserrat orchid (Epidendrum montserratense) from dead trees on the island and installed them in the security of the island's botanic garden.

Montserrat is also home to the critically endangered giant ditch frog (Leptodactylus fallax), known locally as the mountain chicken, found only in Montserrat and Dominica. The species has undergone catastrophic declines due to the amphibian disease Chytridiomycosis and the volcanic eruption in 1997. Experts from Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust have been working with the Montserrat Department of Environment to conserve the frog in-situ in a project called "Saving the Mountain Chicken",[61] and an ex-situ captive breeding population has been set up in partnership with Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, Zoological Society of London, Chester Zoo, Parken Zoo, and the Governments of Montserrat and Dominica. Releases from this programme have already taken place in a hope to increase the numbers of the frog and reduce extinction risk from Chytridiomycosis.

The national bird is the endemic Montserrat oriole (Icterus oberi).[62] The IUCN Red List classifies it as vulnerable, having previously listed it as critically endangered.[63] Captive populations are held in several zoos in the UK including: Chester Zoo, London Zoo, Jersey Zoo and Edinburgh Zoo.

The Montserrat galliwasp (Diploglossus montisserrati), a type of lizard, is endemic to Montserrat and is listed on the IUCN Red List as critically endangered.[64][65] A species action plan has been developed for this species.[66]

In 2005, a biodiversity assessment for the Centre Hills was conducted. To support the work of local conservationists, a team of international partners, including Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Royal Society for the Protection of Birds and Montana State University, carried out extensive surveys and collected biological data.[67] Researchers from Montana State University found that the invertebrate fauna was particularly rich on the island. The report found that the number of invertebrate species known to occur in Montserrat is 1241. The number of known beetle species is 718 species from 63 families. It is estimated that 120 invertebrates are endemic to Montserrat.[67]

Montserrat is known for its coral reefs and its caves along the shore. These caves house many species of bats, and efforts are underway to monitor and protect the ten species of bats from extinction.[68][69]

The Montserrat tarantula (Cyrtopholis femoralis) is the only species of tarantula native to the island. It was first bred in captivity at the Chester Zoo in August 2016.[70]

Climate

[edit]Montserrat has a tropical rainforest climate (Af according to the Köppen climate classification) with the temperature being warm and consistent year-round, and lots of precipitation. Summer and autumn are wetter because of Atlantic hurricanes.

| Climate data for Plymouth | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 32 (90) |

33 (91) |

34 (93) |

34 (93) |

36 (97) |

37 (99) |

37 (99) |

37 (99) |

36 (97) |

34 (93) |

37 (99) |

33 (91) |

37 (99) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 29 (84) |

30 (86) |

31 (88) |

31 (88) |

32 (90) |

32 (90) |

33 (91) |

33 (91) |

32 (90) |

31 (88) |

30 (86) |

29 (84) |

31 (88) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 23 (73) |

23 (73) |

24 (75) |

24 (75) |

24 (75) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

24 (75) |

24 (75) |

24 (75) |

23 (73) |

24 (75) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 17 (63) |

18 (64) |

18 (64) |

18 (64) |

19 (66) |

21 (70) |

22 (72) |

22 (72) |

21 (70) |

19 (66) |

19 (66) |

18 (64) |

17 (63) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 122 (4.8) |

86 (3.4) |

112 (4.4) |

89 (3.5) |

97 (3.8) |

112 (4.4) |

155 (6.1) |

183 (7.2) |

168 (6.6) |

196 (7.7) |

180 (7.1) |

140 (5.5) |

1,640 (64.6) |

| Source: BBC Weather[71] | |||||||||||||

Economy

[edit]

Montserrat's economy was devastated by the 1995 eruption and its aftermath;[29] currently the island's operating budget is largely supplied by the British government and administered through the Department for International Development (DFID) amounting to approximately £25 million per year.[citation needed] Additional amounts are secured through income and property taxes, licence and other fees as well as customs duties levied on imported goods.

The limited economy of Montserrat, with a population under 5000, consumes 2.5 MW of electric power,[72] produced by five diesel generators.[73] Two exploratory geothermal wells have found good resources and the pad for a third geothermal well was prepared in 2016.[74] Together the geothermal wells are expected to produce more power than the island requires.[75] A 250 kW solar PV station was commissioned in 2019, with plans for another 750 kW.[72]

A report published by the CIA indicates that the value of exports totalled the equivalent of US$5.7 million (2017 est.), consisting primarily of electronic components, plastic bags, apparel, hot peppers, limes, live plants and cattle. The value of imports totalled US$31.02 million (2016 est.), consisting primarily of machinery and transportation equipment, foodstuffs, manufactured goods, fuels and lubricants.[6]

In 1979, The Beatles producer George Martin opened AIR Studios Montserrat,[76] making the island popular with musicians who often went there to record while taking advantage of the island's climate and beautiful surroundings.[77] In the early hours of 17 September 1989, Hurricane Hugo passed the island as a Category 4 hurricane, damaging more than 90% of the structures on the island.[19] AIR Studios Montserrat closed, and the tourist economy was virtually wiped out.[78] The slowly recovering tourist industry was again wiped out with the eruption of the Soufrière Hills Volcano in 1995, although it began partially to recover within fifteen years.[79]

Transport

[edit]

Air

[edit]John A. Osborne Airport is the only airport on the island (constructed after the W. H. Bramble Airport was destroyed in 1997 by the volcanic eruption). Scheduled service to Antigua is provided by FlyMontserrat[80] and ABM Air.[81] Charter flights are also available to the surrounding islands.

Sea

[edit]Ferry service to the island was provided by the Jaden Sun Ferry. It ran from Heritage Quay in St. John's, Antigua and Barbuda to Little Bay on Montserrat. The ride was about an hour and a half and operated five days a week.[82]

This service stopped in 2019 due to being financially unsustainable[citation needed] and the only access to Montserrat now is by air.

Demographics

[edit]

Montserrat had a population of 7,119 in 1842.[83]

The island had a population of 5,879 (according to a 2008 estimate). An estimated 8,000 refugees left the island (primarily to the UK) following the resumption of volcanic activity in July 1995; the population was 13,000 in 1994. The 2011 Montserrat census indicated a population of 4,922.[84] In early 2016, the estimated population had reached nearly 5,000 primarily due to immigration from other islands.[10]

Age structure (2003 estimates):

- up to 14 years: 23.4% (male 1,062; female 1,041)

- 15 to 64 years: 65.3% (male 2,805; female 3,066)

- 65 years and over: 11.3% (male 537; female 484)

The median age of the population was 28.1 as of 2002 and the sex ratio was 0.96 males/female as of 2000.

The population growth rate is 6.9% (2008 est.), with a birth rate of 17.57 births/1,000 population, death rate of 7.34 deaths/1,000 population (2003 est.), and net migration rate of 195.35/1,000 population (2000 est.) There is an infant mortality rate of 7.77 deaths/1000 live births (2003 est.). The life expectancy at birth is 75.9 years: 76.8 for males and 75.0 for females (2023 est.).[85] Globally, only Montserrat has a higher life expectancy for males than females, a difference of 1.8 years.[86] The total fertility rate is 1.8 children born/woman (2003 est.).

According to the Montserrat government's 2024 population census, the island has a total population of 4,386, a 10.9% drop compared to 2011.[87]

Language

[edit]English is the sole official language and the main spoken language. A few thousand people speak Montserrat Creole, a dialect of Leeward Caribbean Creole English.[88][89] Historically, Irish Gaelic was spoken, but has disappeared from use.[90]

Irish language in Montserrat

[edit]The Irish constituted the largest proportion of the white population from the founding of the colony in 1628. Most were indentured servants; others were merchants or plantation owners. The geographer Thomas Jeffrey claimed in The West India Atlas (1780) that the majority of those on Montserrat were either Irish or of Irish descent, "so that the use of the Irish language is preserved on the island, even among the Negroes."[91]

African slaves and Irish indentured servants of all classes were in constant contact, with sexual relationships being common and a population of mixed descent appearing as a consequence.[92] The Irish were also prominent in Caribbean commerce, with their merchants importing Irish goods such as beef, pork, butter and herring, and also importing slaves.[93]

There is indirect evidence that the use of the Irish language continued in Montserrat until at least the middle of the nineteenth century. The County Kilkenny diarist and Irish scholar Amhlaoibh Ó Súilleabháin noted in 1831 that he had heard that Irish was still spoken in Montserrat by both black and white inhabitants.[94]

In 1852, Henry H. Breen wrote in Notes and Queries that "The statement that 'the Irish language is spoken in the West India Islands, and that in some of them it may be said to be almost vernacular,' is true of the little Island of Montserrat, but has no foundation with respect to the other colonies."[95]

In 1902, The Irish Times quoted the Montreal Family Herald in a description of Montserrat, noting that "the negroes to this day speak the old Irish Gaelic tongue, or English with an Irish brogue. A story is told of a Connaught man who, on arriving at the island, was, to his astonishment, hailed in a vernacular Irish by the black people."[96]

A letter by W. F. Butler in The Atheneum (15 July 1905) quotes an account by a Cork civil servant, C. Cremen, of what he had heard from a retired sailor called John O'Donovan, a fluent Irish speaker:

He frequently told me that in the year 1852, when mate of the brig Kaloolah, he went ashore on the island of Montserrat which was then out of the usual track of shipping. He said he was much surprised to hear the negroes actually talking Irish among themselves, and that he joined in the conversation...[94]

The British phonetician John C. Wells conducted research into speech in Montserrat in 1977–78 (which included also Montserratians resident in London).[97] He found media claims that Irish speech, whether Anglo-Irish or Irish Gaelic, influenced contemporary Montserratian speech were largely exaggerated.[97] He found little in phonology, morphology or syntax that could be attributed to Irish influence, and in Wells' report, only a small number of Irish words in use, one example being minseach [ˈmʲiɲʃəx] which he suggests is the noun goat.[97]

Religion

[edit]In 2001, the CIA estimated the primary religion as Protestant (67.1%, including Anglican 21.8%, Methodist 17%, Pentecostal 14.1%, Seventh-day Adventist 10.5%, and Church of God 3.7%), with Catholics constituting 11.6%, Rastafarian 1.4%, other 6.5%, none 2.6%, unspecified 10.8%.[6] By 2018, the statistics were Protestant 71.4% (includes Anglican 17.7%, Pentecostal/Full Gospel 16.1%, Seventh Day Adventist 15%, Methodist 13.9%, Church of God 6.7%, other Protestant 2%), Roman Catholic 11.4%, Rastafarian 1.4%, Hindu 1.2%, Jehovah's Witness 1%, Muslim 0.4%, unspecified 5.1%, none 7.9% (2018 est.)[98]

Ethnic groups

[edit]Residents of Montserrat are known as Montserratians. The population is predominantly, but not exclusively, of mixed African-Irish descent.[99] It is not known with certainty how many African slaves and indentured Irish labourers were brought to the West Indies, though according to one estimate some 60,000 Irish were "Barbadosed" by Oliver Cromwell,[100] some of whom would have arrived in Montserrat.

Data published by the Central Intelligence Agency indicates the ethnic group mix as follows (2011 est.):[6]

- 88.4%: African/black

- 3.7%: mixed

- 3.0%: Hispanic/Spanish (of any race, including white)

- 2.7%: non-Hispanic Caucasian/white

- 1.5%: East Indian/Indian

- 0.7%: other

As of 2018 the statistics were estimated at:[98]

- African/Black 86.2%,

- mixed 4.8%

- Hispanic/Spanish 3%

- Caucasian/White 2.7%

- East Indian/Indian 1.6%

- other 1.8%

Education

[edit]Education in Montserrat is compulsory for children between the ages of 5 and 14, and free up to the age of 17. The only secondary school (pre-16 years of age) on the island is the Montserrat Secondary School (MSS) in Salem.[101] Montserrat Community College (MCC) is a community college (post-16 and tertiary educational institution) in Salem.[102] The University of the West Indies maintains its Montserrat Open Campus.[103] University of Science, Arts and Technology is a private medical school in Olveston.[104]

Culture

[edit]This article is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (May 2016) |

For more than a decade, George Martin's AIR Montserrat studio played host to recording sessions by many well known rock musicians, including Dire Straits, the Police, Rush, Elton John, Michael Jackson, and the Rolling Stones.[77] After the volcanic eruptions of 1995 through 1997, and until his death in 2016, George Martin raised funds to help the victims and families on the island. The first event was a star-studded event at London's Royal Albert Hall in September 1997, Music for Montserrat, featuring many artists who had previously recorded on the island including Paul McCartney, Mark Knopfler, Elton John, Sting, Phil Collins, Eric Clapton, and Midge Ure. The event raised £1.5 million.[105] All the proceeds from the show went towards short-term relief for the islanders.[77]

Martin's second major initiative was to release five hundred limited edition lithographs of his score for the Beatles song "Yesterday". Complete with mistakes and tea stains, the lithographs are numbered and signed by Paul McCartney and Martin. The lithograph sale raised more than US$1.4 million, which helped fund the building of a new cultural and community centre for Montserrat and provided a much needed focal point to help the re-generation of the island.[77]

Many albums of note were recorded at AIR Studios, including Rush's Power Windows, Dire Straits' Brothers in Arms, Duran Duran's Seven and the Ragged Tiger, the Police's Synchronicity and Ghost in the Machine (videos for "Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic" and "Spirits in the Material World" were filmed in Montserrat), and Jimmy Buffett's Volcano (named for Soufrière Hills).[77] Ian Anderson (of Jethro Tull) recorded the song "Montserrat" on The Secret Language of Birds in tribute to the volcanic difficulties and feeling among residents of being abandoned by the UK government.

Media

[edit]Montserrat has one national radio station, Radio Montserrat. The station offers a wide selection of music and news within the island and also on the internet for Montserratians living overseas.

Notable shows include the Morning Show with Basil Chambers and Rose Willock's Cultural Show.

In 2017, Montserrat was used to film much of the 2020 film Wendy.[106]

In 2023, the documentary called Ben Fogle And The Buried City aired on Channel 5 in the UK. "Ben explores the abandoned capital of Plymouth, now an ash-covered, ghost town that provides a glimpse into the thriving capital it once was".[107] It also premiered at the Montserrat Cultural Centre which drew a large audience who were eager to watch the film.[108]

Cuisine

[edit]Montserrat's national dish is goat water, a thick goat meat stew served with crusty bread rolls.[10] Montserrat cuisine resembles the general British and Caribbean cuisines, as it is situated in the Caribbean zone and it is a British territory. The cuisine includes a wide range of light meats, like fish, seafood and chicken, which are mostly grilled or roasted. Being a fusion of numerous cultures, such as Spanish, French, African, Indian and Amerindian, the Caribbean cuisine is unique and complex. More sophisticated meals include the Montserrat jerk shrimp, with rum, cinnamon bananas and cranberry. In other more rural areas, people prefer to eat homemade food, like the traditional mahi mahi and local breads.

Sport

[edit]Yachting

[edit]Montserrat is home to the Montserrat Yachting Association.[109]

Athletics

[edit]Montserrat has competed in every Commonwealth Games since 1994.[110]

Miguel Francis who now represents the United Kingdom and previously represented Antigua and Barbuda was born in Montserrat. He holds the Antiguan National record over 200m in 19.88.[111][112]

Basketball

[edit]Basketball is growing in popularity in Montserrat with the country now setting up their own basketball league.[113][114] The league contains six teams, which are the Look-Out Shooters, Davy Hill Ras Valley, Cudjoe Head Renegades, St. Peters Hilltop, Salem Jammers and MSS School Warriors.[115] They have also built a new 800 seater complex which cost $1.5 million.

Cricket

[edit]In common with many Caribbean islands, cricket is a very popular sport in Montserrat. Players from Montserrat are eligible to play for the West Indies cricket team. Jim Allen was the first to play for the West Indies and he represented the World Series Cricket West Indians, although, with a very small population, no other player from Montserrat had gone on to represent the West Indies until Lionel Baker made his One Day International debut against Pakistan in November 2008.[116]

The Montserrat cricket team forms a part of the Leeward Islands cricket team in regional domestic cricket; however, it plays as a separate entity in minor regional matches,[117] as well having previously played Twenty20 cricket in the Stanford 20/20.[118] Two grounds on the island have held first-class matches for the Leeward Islands, the first and most historic was Sturge Park in Plymouth, which had been in use since the 1920s. This was destroyed in 1997 by the volcanic eruption. A new ground, the Salem Oval, was constructed and opened in 2000. This has also held first-class cricket. A second ground has been constructed at Little Bay.[119]

Football

[edit]Montserrat has its own FIFA affiliated football team, and has competed in the World Cup qualifiers five times but failed to advance to the finals from 2002 to 2018. A field for the team was built near the airport by FIFA. In 2002, the team competed in a friendly match with the second-lowest-ranked team in FIFA at that time, Bhutan, in The Other Final, the same day as the final of the 2002 World Cup. Bhutan won 4–0. Montserrat has failed to qualify for any FIFA World Cup. They have also failed to ever qualify for the Gold Cup and Caribbean Cup. The current national team relies mostly on the diaspora resident in England and in the last World Cup qualification game against Curaçao nearly all the squad members played and lived in England.[citation needed]

Montserrat has a club league, the Montserrat Championship, which has played sporadically since 1974. The league was most recently on hiatus from 2005 until 2015 but restarted play in 2016.

Surfing

[edit]

Carrll Robilotta, whose parents moved from the United States to Montserrat in 1980, was responsible for pioneering the sport of surfing on the island. He and his brother Gary explored, discovered, and named the surf spots on the island during the 80s and early 90s.[120]

Settlements

[edit]

Settlements within the exclusion zone are no longer habitable. See also List of settlements abandoned after the 1997 Soufrière Hills eruption.

Settlements in the safe zone

[edit]- Baker Hill

- Banks

- Barzeys

- Blakes

- Brades

- Carr's Bay

- Cavalla Hill

- Cheap End

- Cudjoe Head

- Davy Hill

- Dick Hill

- Drummonds

- Flemmings

- Fogarty

- Frith

- Garibaldi Hill

- Gerald's[c]

- Hope

- Jack Boy Hill

- Judy Piece

- Katy Hill

- Lawyers Mountain

- Little Bay

- Lookout

- Manjack

- Mongo Hill

- New Windward Estate

- Nixons

- Old Towne

- Olveston

- Peaceful Cottage

- Salem

- Shinlands

- St. John's

- St. Peter's

- Sweeney's

- Woodlands

- Yellow Hill

Abandoned settlements in the exclusion zone

[edit]Settlements in italics have been destroyed by pyroclastic flows since the 1997 eruption. Others have been evacuated or destroyed since 1995.

- Amersham

- Beech Hill

- Bethel

- Bramble

- Bransby

- Bugby Hole

- Cork Hill

- Dagenham

- Delvins

- Dyers

- Elberton

- Farm

- Fairfield

- Fairy Walk

- Farrells

- Farells Yard

- Ffryes

- Fox's Bay

- Gages

- Gallways Estate

- Gringoes

- Gun Hill

- Happy Hill

- Harris

- Harris Lookout

- Hermitage

- Hodge's Hill

- Jubilee

- Kinsale

- Lees

- Locust Valley

- Long Ground

- Molyneux

- Morris

- Parsons

- Plymouth

- Richmond

- Richmond Hill

- Roche's Yard

- Robuscus Mt

- Shooter's Hill

- Soufrière

- Spanish Point

- St. George's Hill

- St. Patrick's

- Streatham

- Trants

- Trials

- Tuitts

- Victoria

- Webbs

- Weekes

- White's

- Windy Hill

Notable Montserratians

[edit]- Jim Allen, former cricketer who represented the World Series Cricket West Indians

- Jennette Arnold, the first Montserratian elected as a Member of the London Assembly.

- Lionel Baker, the first Montserratian to represent the West Indies in international cricket

- Alphonsus "Arrow" Cassell, musician known for his soca song "Hot Hot Hot"

- Chadd Cumberbatch, visual and performing artist, poet and playwright.

- Margaret Dyer-Howe, Montserrat's second woman to be appointed a cabinet minister.

- Ettore Ewen, American professional wrestler and former WWE Heavyweight Champion, 11-time tag team champion, former college football player and powerlifter.

- Howard A. Fergus, author, poet and three time acting governor of Montserrat

- Patricia Griffin, pioneer nurse and volunteer social worker

- George Irish, writer, human rights activist

- Kadiff Kirwan, actor

- E. A. Markham, poet and author

- Dean Mason, association footballer

- Ellen Dolly Peters, teacher and trade unionist

- Q-Tip, rapper, songwriter and producer; his father emigrated to Cleveland, United States from Montserrat

- Shane Ryan, writer, human rights activist

- Veronica Ryan, sculptor, and winner of the 2022 Turner Prize

- M. P. Shiel, writer

- Lyle Taylor, association footballer

- Rowan Taylor, international footballer

- Maizie Williams, member of pop group Boney M

- Angela Yee, member of the syndicated morning radio show The Breakfast Club

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Abandoned in 1997, following a volcanic eruption, although it is still the de jure capital.

- ^ Government buildings are now located in Brades, making it the de facto capital.

- ^ Includes the new airport in the north of the island.

References

[edit]- ^ "Change of Governor of Montserrat: Sarah Tucker". Gov.uk. 8 December 2021. Archived from the original on 12 March 2022. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ "World Population Prospects 2022". population.un.org. United Nations. 2022. Archived from the original on 16 August 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ "Intercensal Population Count and Labour Force Survey 2018" (PDF). Montserrat Statistics Department Labour Force Census Results. Montserrat Statistics Department. 6 December 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 November 2019. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- ^ "UN Data". 2014. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ "Montserrat Real Gross Domestic Product | Moody's Analytics". economy.com. Archived from the original on 10 August 2021. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Central America :: Montserrat — The World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency". Cia.gov. Archived from the original on 18 February 2021. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ^ "The Caribbean Irish: the other Emerald Isle". The Irish Times. 16 April 2016. Archived from the original on 16 April 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ "► VIDEO: Montserrat, the Emerald Isle of the Caribbean". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 28 June 2023. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ a b "Montserrat Volcano Observatory". Mvo.ms. Archived from the original on 2 October 2006. Retrieved 2 October 2006.

- ^ a b c Schuessler, Ryan (14 February 2016). "20 years after Montserrat volcano eruption, many still in shelter housing". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 27 November 2022. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

Montserrat's population has grown to nearly 5,000 people since the eruption — mostly due to an influx of immigrants from other Caribbean nations.

- ^ Bachelor, Blane (20 February 2014). "Montserrat: a modern-day Pompeii in the Caribbean". Fox News Channel. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ^ Pilley, Kevin (29 February 2016). "Bar/fly: Caribbean island of Montserrat". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 28 June 2023. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ^ Handy, Gemma (16 August 2015). "Montserrat: Living with a volcano". BBC News. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ^ "Hurricanes Irma and Maria: government response and advice". GOV.UK. 27 September 2017. Archived from the original on 2 July 2022. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ "UK Armed Forces step up support to the Caribbean Overseas Territories during coronavirus pandemic". GOV.UK. Archived from the original on 2 July 2022. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ Minahan, James (1 December 2009). The Complete Guide to National Symbols and Emblems: Volume 2. Greenwood Press. p. 724. ISBN 978-0-313-34500-5. Archived from the original on 3 October 2023. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ^ Cherry, John F.; Ryzewski, Krysta; Leppard, Thomas P. & Bocancea, Emanuela (September 2012). "The earliest phase of settlement in the eastern Caribbean: new evidence from Montserrat". Antiquity. 86 (333). Archived from the original on 20 June 2017. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ^ Reid, Basil A. (2009). Myths and Realities of Caribbean History. University of Alabama Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0817355340.

However, archaeological investigations of the very large site of Trants in Montserrat ... [suggest that Trants was] one of the largest Saladoid sites in the Caribbean.

- ^ a b c d e f "Encyclopædia Britannica – Monts/errat". Archived from the original on 17 October 2022. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ a b "Hikers on Caribbean island of Montserrat find ancient stone carvings". the Guardian. 3 June 2016. Archived from the original on 18 October 2022. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- ^ a b Cherry, John F.; Ryzewski, Krysta; Guimarães, Susana; Stouvenot, Christian; Francis, Sarita (June 2021). "The Soldier Ghaut Petroglyphs on Montserrat, Lesser Antilles". Latin American Antiquity. 32 (2): 422–430. doi:10.1017/laq.2020.102. ISSN 1045-6635. S2CID 233932699. Archived from the original on 18 October 2022. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- ^ Bergreen, Laurence (2011). Columbus: The Four Voyages. Viking. p. 140. ISBN 9780670023011.

At daybreak on November 10, Columbus and his fleet departed from Guadeloupe, sailing northwest along the coast to the island of Montserrat. The handful of Indians aboard his ship explained that the island had been ravaged by the Caribs, who had 'eaten all its inhabitants'.

- ^ a b c d Roberts-Wray, Kenneth (1966). Commonwealth and Colonial Law. London: Stevens. p. 855.

- ^ a b c "The Island of Montserrat". The Illustrated London News. 106 (Summer Number): 37. 1895 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Roberts-Wray, Kenneth (1966). Commonwealth and Colonial Law. London: Stevens. p. 856.

- ^ a b c d e "Brown Archaeology- Montserrat". 9 July 2015. Archived from the original on 4 June 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ Akenson, Donald H. (1997). "Ireland's neo-Feudal Empire, 1630–1650". If the Irish ran the world: Montserrat, 1630–1730. McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 12–57, 273. ISBN 978-0-7735-1686-1. Archived from the original on 3 October 2023. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ^ Fergus, Howard A. (1996). Gallery Montserrat: some prominent people in our history. Canoe Press, University of West Indies. p. 83. ISBN 976-8125-25-X. Archived from the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "Encyclopaedia Britannica - Montserrat". Archived from the original on 17 October 2022. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ "Montserrat's St. Patrick's Day Commemorates a Rebellion". JSTOR Daily. 16 March 2021. Archived from the original on 20 March 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ O'Shaughnessy, A. J. (2006). "Caribbean". In Boatner, III, M. M. (ed.). Landmarks of the American Revolution: Library of Military History (2nd ed.). Detroit, MI: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 33. ISBN 9780684314730. Archived from the original on 3 October 2023. Retrieved 20 September 2020 – via Gale Virtual Reference.

- ^ "Slavery Abolition Act 1833; Section XII". 28 August 1833. Archived from the original on 24 May 2008. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ^ Beckles, Hilary McD (1998). "Caribbean Region: English Colonies". In Finkelman, Paul; Miller, Joseph Calder (eds.). Macmillan Encyclopedia of World Slavery. Vol. 1. Simon & Schuster Macmillan. pp. 154–159. ISBN 9780028647807.

- ^ Finkleman, Paul; Calder Miller, Joseph, eds. (1998). "Plantations: Brazil". Macmillan Encyclopedia of World Slavery. Macmillan Reference USA. Archived from the original on 28 June 2023. Retrieved 14 February 2018 – via GALE World History in Context.

- ^ "The Island of Montserrat". The Illustrated London News. 106 (Summer Number): 37. 1895 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Sturge, Joseph Edward (March 2004). "The Montserrat Connection". Sturgefamily.com. Archived from the original on 4 January 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ^ "Montserrat". Commonwealth Secretariat. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 30 January 2007.

- ^ Hendry, Ian; Dickson, Susan (2011). British Overseas Territories Law. Oxford: Hart Publishing. p. 325. ISBN 9781849460194. Archived from the original on 3 October 2023. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ Gallery Montserrat: some prominent people in our history By Howard A. Fergus. Publisher: Canoe Press University of the West Indies. ISBN 978-976-8125-25-5 / ISBN 976-8125-25-X [1] Archived 28 June 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Robert J Alexander & Eldon M Parker (2004) A History of Organized Labor in the English-speaking West Indies, Greenwood Publishing Group, p144

- ^ "The Caribbean Territories (Abolition of Death Penalty for Murder) Order 1991". Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 28 June 2023. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ a b South America, Central America and the Caribbean 2002, Psychology Press, p565

- ^ "Attorney-at-Law David S. Brandt Has Been Remanded into Custody at Her Majesty's Prison on Montserrat". mnialive.com. Archived from the original on 28 June 2019. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ "Montserrat: Ex chief minister sentenced in sexual exploitation case". 19 July 2021. Archived from the original on 22 December 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ Radio Jamaica[permanent dead link], New MCPR Gov't in Montserrat, 9 September 2009. Retrieved 10 September 2009.

- ^ "Update on Caribbean IP Offices Following Hurricanes Irma and Maria". Inta.org. Archived from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ^ "Montserrat Government Profile 2018". Indexmundi.com. Archived from the original on 28 June 2023. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ^ Kowalski, Jeff (11 September 2009). "Central America and Caribbean: Monserrat". Archived from the original on 28 June 2023. Retrieved 26 October 2009.

- ^ Wittebol, Hans. "The Parishes of Montserrat". Statoids.com. Archived from the original on 28 June 2023. Retrieved 26 October 2009.

- ^ "Montserrat: Census Regions & Villages - Population Statistics, Maps, Charts, Weather and Web Information". Citypopulation.de. Archived from the original on 7 May 2023. Retrieved 3 October 2023.

- ^ "HMS Medway sets sail for the Caribbean". Archived from the original on 10 May 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ "HMS Dauntless visits trio of Caribbean Islands in disaster relief preparation mission". Royal Navy. 4 October 2023. Archived from the original on 4 October 2023. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- ^ "People's TV". Raffa. Archived from the original on 21 September 2014.

- ^ "Postcode guide pamphlet" (PDF). Gov.ms. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ^ Leonard, T. M. (2005). Encyclopedia of the Developing World. Routledge. p. 1083. ISBN 978-1-57958-388-0.

- ^ "Types of British nationality: British overseas territories citizen". British Government. Archived from the original on 23 May 2023. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ^ "Montserrat (British Overseas Territory) travel advice". Travel & living abroad. Foreign and Commonwealth Office. 19 December 2012. Archived from the original on 28 June 2023. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- ^ "Montserrat Hazard Level System Zones" (PDF). Montserrat Volcanic Observatory. 1 August 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 June 2023. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ "Montserrat History & Facts". Archived from the original on 30 May 2023. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ Johnson, Nick (22 October 2010). "The 'Montserrat pribby' (part one)". kew.org. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- ^ "Saving the Mountain Chicken:A Long-Term Recovery Strategy for the Critically Endangered mountain chicken 2014-2034" (PDF). Amphibians.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 August 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ "Montserrat oriole photo - Icterus oberi - G55454". Arkive.org. Archived from the original on 30 November 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ^ BirdLife International. (2017) [amended version of 2017 assessment]. "Icterus oberi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T22724147A119465859. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T22724147A119465859.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ Daltry, J.C. (2017) [errata version of 2016 assessment]. "Diploglossus montisserrati". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T6638A115082920. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T6638A71739597.en. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ^ "Montserrat galliwasp videos, photos and facts - Diploglossus montisserrati". Arkive.org. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ^ Corry, E.; et al. (2010). A Species Action Plan for the Montserrat galliwasp: Diploglossus montisserrati (PDF). Department of Environment, Montserrat. ISBN 978-0-9559034-5-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 February 2017.

- ^ a b Young, Richard P., ed. (2008). "A biodiversity assessment of the Centre Hills, Montserrat" (PDF). Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust. Durrell Conservation Monograph No. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 April 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ^ "Bats". Sustainable Ecosystems Institute. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014.

- ^ Pedersen, Scott C.; Kwiecinski, Gary G.; Larsen, Peter A.; Morton, Matthew N.; Adams, Rick A.; Genoways, Hugh H. & Swier, Vicki J. (1 January 2009). "Bats of Montserrat: Population Fluctuation and Response to Hurricanes and Volcanoes, 1978–2005". ResearchGate. Archived from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- ^ "Montserrat tarantulas hatch in 'world first'". Chester Zoo. 12 August 2016. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- ^ "Average Conditions Plymouth, Montserrat". BBC Weather. Archived from the original on 30 November 2010. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- ^ a b Roach, Bennette. "Is this end of Geothermal Energy development?". Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ "Energy Snapshot: Montserrat" (PDF). NREL. September 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ Richter, Alexander (2 September 2016). "Well pad ready for drilling of third geothermal well in Montserrat". Think Geoenergy. Archived from the original on 24 September 2016. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ^ Handy, Gemma (8 November 2015). "Does Montserrat's volcano hold the key to its future?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 3 July 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ "Sir George Martin CBE (1926–2016)". George Martin Music. 2017. Archived from the original on 24 July 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ^ a b c d e "AIR Montserrat". AIR Studios. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- ^ National Research Council (1994). Hurricane Hugo, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and Charleston, South Carolina, September 17-22, 1989. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/1993. ISBN 978-0-309-04475-2.

- ^ "Montserrat tourism arrivals up 22 percent in first seven months of 2010 | Caribbean news, Entertainment, Fashion, Politics, Business, Sports..." www.thewestindiannews.com. Archived from the original on 19 May 2015. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- ^ "FlyMontserrat flight schedule". Archived from the original on 1 May 2023. Retrieved 16 May 2019. Retrieved on 16 May 2019

- ^ "ABM route map". Archived from the original on 16 December 2014. Retrieved 16 May 2019. Retrieved on 16 May 2019.

- ^ "Jaden Sun Ferry Schedule". Archived from the original on 4 June 2023. Retrieved 16 May 2019. Retrieved on 16 May 2019

- ^ The National Cyclopaedia of Useful Knowledge, Vol.IV. London: Charles Knight. 1848. p. 772.

- ^ "Census 2011 At a Glance" (PDF). Government of Montserrat. Statistics Department, Montserrat. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ^ "Life expectancy at birth - The World Factbook". www.cia.gov. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 3 April 2024.

- ^ "List of Countries by Life Expectancy 2023 | life —— lines". 22 January 2024. Archived from the original on 3 April 2024. Retrieved 3 April 2024.

- ^ de Shong, Dillon (21 April 2024). "Census shows Montserrat's population is declining". Loop Caribbean News. Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics. Elsevier. 24 November 2005. ISBN 9780080547848. Archived from the original on 5 August 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2022 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Montserrat | Facts, Map, & History | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Archived from the original on 17 October 2022. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ Barzey, Ursula Petula (30 August 2022). "Timeline, History, and Cultural Legacy of the Irish in Montserrat - Black Irish of Montserrat". Archived from the original on 10 October 2022. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ Cited in: Truxes, Thomas M. (2004). Irish-American Trade, 1660-1783. Cambridge University Press. p. 100. See also: The late Thomas Jefferys, Geographer to the King (1780). The West India Atlas or, A Compendious Description of the West-Indies. Fleet Street, London: Robert Sayer and John Bennett.

- ^ Rodgers, Nini (November 2007). "The Irish in the Caribbean 1641-1837: An Overview". Irish Migration Studies in Latin America. 5 (3): 145–156. Archived from the original on 27 September 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ^ McGarrity, Maria (2008). Washed by the Gulf Stream: The Historic and Geographic Relation of Irish and Caribbean Literature. Associated University Presses. pp. 33–34. ISBN 9780874130287.

- ^ a b De Bhaldraithe, Tomás, ed. (1979). "Entry 2700, 1 Aibreán 1831 [1 April 1831]". Cín Lae Amhlaoibh (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: An Clóchomhar Tta. p. 84.

Is clos dom gurb í an teanga Ghaeilge is teanga mháthartha i Monserrat san India Thiar ó aimsir Olibher Cromaill, noch do dhíbir cuid de chlanna Gael ó Éirinn gusan Oileán sin Montserrat. Labhartar an Ghaeilge ann go coiteann le daoine dubha agus bána. [I heard that the Irish language is the mother tongue in Montserrat in the West Indies since the time of Oliver Cromwell, who banished some Gaelic Irish families there. Irish speaking is common among both blacks and whites.]

- ^ "Notes and Queries: A Medium of Inter-Communication for Literary Men, Artists, Antiquaries, Genealogists, Etc". Bell. 15 July 1852. Archived from the original on 3 October 2023. Retrieved 20 September 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ The Irish Times (Monday, 8 September 1902), page 5.

- ^ a b c Wells, John C. (1980). "The brogue that isn't". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 10 (1–2): 74–79. doi:10.1017/s0025100300002115. S2CID 144941139. Archived from the original on 16 March 2023. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- ^ a b "Montserrat", The World Factbook, Central Intelligence Agency, 10 September 2024, retrieved 17 September 2024

- ^ McGinn, Brian. "How Irish is Montserrat? (The Black Irish)". RootsWeb.com. Archived from the original on 9 July 2023. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- ^ "Barbadosed: Africans and Irish in Barbados". Tangled Roots. Archived from the original on 8 December 2014.

- ^ "Territories and Non-Independent Countries". 2001 Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor. Bureau of International Labor Affairs, US Department of Labor. 2002. Archived from the original on 28 March 2005.

- ^ Home page Archived 16 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine. Montserrat Community College. Retrieved 24 November 2017. "Salem, Montserrat W. I."

- ^ "The Open Campus in Montserrat Archived 27 May 2023 at the Wayback Machine." University of the West Indies Open Campus. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- ^ "Contact USAT Archived 1 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine." University of Science, Arts and Technology. Retrieved 24 November 2017. "Main Campus: South Mayfield Estate Drive, Olveston, Montserrat"

- ^ "The story behind 'Music for Montserrat' at Royal Albert Hall". Dire Straits Blog. 23 September 2017. Archived from the original on 13 July 2020. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ Varun, Patel (27 February 2020). "Which Island Was "Wendy" Filmed On?". TheCinemaholic. Archived from the original on 30 November 2021. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- ^ "Ben Fogle And The Buried City | Preview (Channel 5)". www.tvzoneuk.com. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ^ "Montserrat Tourism Division Announces Successful Premiere of Channel 5, Ben Fogle and the Buried City Documentary – Government of Montserrat". Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ^ AlMirSoft. "Yacht registration, training and certification of yachtsmen". Montserrat Yachting Association. Archived from the original on 13 September 2016. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ^ "Commonwealth Games Countries: Montserrat". Commonwealth Games Federation. Archived from the original on 26 June 2014. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- ^ ""IT WAS SUCH AN EUPHORIC MOMENT" MANAGER SAYS OF FRANCIS' 19.88". trackalerts.com. 21 June 2016. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ "Francis moved to Antigua and Barbuda after a volcanic eruption on the island in 1995 displaced him and his family". skysports. Archived from the original on 31 December 2022. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ "Montserrat Volcanos". Montserrat Amateur Basketball Association. Archived from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ^ "Village basketball league makes a comeback". The Montserrat Reporter. 11 July 2012. Archived from the original on 4 June 2023. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ^ Cassell, Warren (18 July 2015). "Montserrat 2015 basketball Championship game Salem Jammers vs. Lookout Shooters". Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2017 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Late Show Wins It For Pakistan In Abu Dhabi". CricketWorld.com. 12 November 2008. Archived from the original on 24 July 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ^ "Other Matches played by Montserrat". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ^ "Twenty20 Matches played by Montserrat". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- ^ "Island of Montserrat". Foreign and Commonwealth Office. Archived from the original on 1 July 2012. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ^ "Montserrat Boardriders Club - About Us". www.montserratsurfvilla.com. Archived from the original on 16 August 2022. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ "Little Bay Development". Government of the United Kingdom. 2010. Archived from the original on 25 April 2013.

Further reading

[edit]- Akenson, Donald Harman – If the Irish Ran the World: Montserrat, 1630-1730.[1][2][3][4]

- Brussell, David Eric – Potions, Poisons, and Panaceas: An Ethnobotanical Study of Montserrat.[5][6][7]

- Dobbin, Jay D. – The Jombee Dance of Montserrat: A Study of Trance Ritual in the West Indies.[8][9]

- Perrett, Frank A. – The Volcano-Seismic Crisis at Montserrat, 1933-37.[10]

- Philpott, Stuart B. – West Indian Migration: The Montserrat Case.[11]

- Possekel, Anja K. – Living with the Unexpected: Linking Disaster Recovery to Sustainable Development in Montserrat.[12]

External links

[edit]Government

[edit]- Government of Montserrat Archived 14 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Montserrat National Trust Archived 22 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Premier of Montserrat

General information

[edit]- Montserrat Archived 14 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- Montserrat from UCB Libraries GovPubs.

- Montserrat Webdirectory

- Story of the black Irish in Montserrat Archived 18 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine

Wikimedia Atlas of Montserrat

Wikimedia Atlas of Montserrat

News media

[edit]- Montserrat Reporter news site

- Radio Montserrat—ZJB Listen live online Archived 14 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine

Travel

[edit]- Montserrat Tourist Board Archived 12 March 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- Montserrat Magazine Publications Archived 9 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- Montserrat Magazine Archived 30 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine

Health reports

[edit]- Toxicity of volcanic ash from Montserrat Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine by RT Cullen, AD Jones, BG Miller, CL Tran, JMG Davis, K Donaldson, M Wilson, V Stone, and A Morgan. Institute of Occupational Medicine Research Report TM/02/01.

- A Health Survey of Workers on the Island of Montserrat Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine by HA Cowie, MK Graham, A Searl, BG Miller, PA Hutchison, C Swales, S Dempsey, and M Russell. Institute of Occupational Medicine Research Report TM/02/02.

- A Health Survey of Montserratians Relocated to the UK Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine by HA Cowie, A Searl, PJ Ritchie, MK Graham, PA Hutchison, and A Pilkington. Institute of Occupational Medicine Research Report TM/01/07.

Others

[edit]- Montserrat Volcano Observatory

- Official release archive Archived 19 March 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- Antigua, Montserrat and Virgin Islands Gazette Archived 21 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine at the Digital Library of the Caribbean

- ^ Solow, Barbara L. (Autumn 1998). "Review". Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 29 (2): 324–326. doi:10.1162/jinh.1998.29.2.324. JSTOR 207075. S2CID 143897485.

- ^ O'Shaughnessy, Andrew J. (December 1998). "Review". The International History Review. 20 (4). Taylor & Francis, Ltd.: 968–970. JSTOR 40108020.

- ^ Ohlmeyer, Jane (November 1998). "Review". Irish Historical Studies. 31 (122): 285–287. doi:10.1017/S0021121400014036. JSTOR 30008270. S2CID 164152541.

- ^ Palmer, Stanley H. (April 1999). "Review". The American Historical Review. 104 (2): 612–613. doi:10.2307/2650471. JSTOR 2650471.

- ^ Boom, B. M. (January–March 1999). "Review". Systematic Botany. 24 (1): 116. doi:10.2307/2419391. JSTOR 2419391. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ Rashford, John (January–March 1999). "Review". Economic Botany. 53 (1): 123. doi:10.1007/bf02860804. JSTOR 4256169. S2CID 13539061.

- ^ Anderson, E. N. (Spring 1999). "Review: Native American Cultural Representations of Flora and Fauna". Ethnohistory. 46 (2). Duke University Press: 378–382. JSTOR 482966.

- ^ Glazier, Stephen D. (July–September 1987). "Review". The Journal of American Folklore. 100 (397): 363–365. doi:10.2307/540351. JSTOR 540351.

- ^ Gissurarson, Loftur R. (Summer 1989). "Review". Sociological Analysis. 50 (2): 195–197. doi:10.2307/3710993. JSTOR 3710993.

- ^ Behre, Charles H. Jr. (May–June 1940). "Review". The Journal of Geology. 48 (4): 447–448. Bibcode:1940JG.....48..447B. doi:10.1086/624903. JSTOR 30058685.

- ^ Foner, Nancy (September 1975). "Review". American Anthropologist. New. 77 (3): 649. doi:10.1525/aa.1975.77.3.02a00500. JSTOR 673440.

- ^ Chester, David K. (June 2001). "Review". The Geographical Journal. 167 (2). Blackwell Publishing on behalf of The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers): 183–184. JSTOR 3060497.

- Montserrat

- Island countries

- British Overseas Territories

- Dependent territories in the Caribbean

- English-speaking countries and territories

- Islands of British Overseas Territories

- Member states of the Caribbean Community

- Member states of the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States

- Small Island Developing States

- Former English colonies

- 1640s establishments in the Caribbean

- 1642 establishments in North America

- 1642 establishments in the British Empire

- States and territories established in 1962

- 1960s establishments in the Caribbean

- 1962 establishments in North America