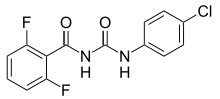

Benzoylurea insecticide

Benzoylureas (BPUs) are chemical derivatives of N-benzoyl-N′-phenylurea, which are used as insecticides.[1] They do not directly kill the insect, but disrupt moulting and egg hatch, and thus act as insect growth regulators. They act by inhibiting chitin synthase,[2] preventing the formation of chitin in the insect's body.

The insecticidal activity of the BPUs was discovered serendipitiously at Phillips-Duphar who commericalised diflubenzuron in 1975.[1] Since then, many BPUs were commercialised by many companies. BPUs accounted for 3% of the $ 18.4 billion world insecticide market in 2018.[3] Lufenuron, was the largest selling BPU in 2016, selling for $ 112 million.[4]

BPUs are active against many types of insect pests, (e.g. lepidoptera coleoptera, diptera) in agriculture,[1][5] as well as being used against termites and animal health pests such as fleas.[6]

The Insecticide Resistance Action Committee (IRAC) lists the following BPUs, which are classified in IRAC group 15.[7] Bistrifluron, Chlorfluazuron, Diflubenzuron, Flucycloxuron, Flufenoxuron, Hexaflumuron, Lufenuron, Novaluron, Noviflumuron, Teflubenzuron, Triflumuron. Many older BPUs are no longer in use.[1][5]

Mammalian and environmental toxicity

[edit]BPUs have a good mammalian tox profile. Diflubenzuron is considered to be of very low acute toxicity, and is approved by the WHO for treatment of drinking water as a mosquito larvicide.[8]

BPUs have low acute toxicity against bees, low to moderate toxicity to fish, but high toxicity to aquatic invertebrates and crustaceans.[1]

BPUs have various rates of degradation in the environment. Some older BPUs have high persistance and are no longer sold.[1] Flufenoxuron was shown to bioaccumulate and was banned in the EU in 2011.[9]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Sun, Ranfeng; Liu, Chunjuan; Hao, Zhang; Wang, Qingmin (July 13, 2015). "Benzoylurea Chitin Synthesis Inhibitors". J. Agric. Food Chem. 63 (31): 6847–6865. Bibcode:2015JAFC...63.6847S. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.5b02460. PMID 26168369.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Douris, Vassilis; Steinbach, Denise; Panteleri, Rafaela; Livadaras, Ioannis; Pickett, John Anthony; Van Leeuwen, Thomas; Nauen, Ralf; Vontas, John (2016). "2016". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (51): 14692–14697. doi:10.1073/pnas.1618258113. PMC 5187681. PMID 27930336.

- ^ Sparks, Thomas C. (14 February 2024). "Insecticide mixtures—uses, benefits and considerations". Pest Management Science. doi:10.1002/ps.7980. PMID 38356314 – via Wiley.

- ^ Jeschke, Peter; Witschel, Matthias; Krämer, Wolfgang; Schirmer, Ulrich (2019). "Chapter 30: Chitin Biosynthesis". Modern Crop Protection Compounds (3rd ed.). Wiley (published 25 January 2019). pp. 1067–1102. ISBN 9783527699261.

- ^ a b Pener, Meir Paul; Dhadialla, Tarlochan S. (2012). "An Overview of Insect Growth Disruptors; Applied Aspects". Advances in Insect Physiology. 43: 1–162. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-391500-9.00001-2. ISBN 9780123915009. ISSN 0065-2806 – via Elsevier.

- ^ Junquera, Pablo; Hosking, Barry; Gameiro, Marta; Macdonald, Alicia (2019). "Benzoylphenyl ureas as veterinary antiparasitics. An overview and outlook with emphasis on efficacy, usage and resistance". Parasite. 26: 26. doi:10.1051/parasite/2019026. ISSN 1776-1042. PMC 6492539. PMID 31041897.

- ^ "The IRAC Mode of Action Classification Online". Insecticide Resistance Action Committee. Retrieved 5 June 2024.

- ^ Guidelines for Drinking‑water Quality (4th ed.). Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2017. pp. 435–436. ISBN 978-92-4-154995-0.

- ^ Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 942/2011 of 22 September 2011 concerning the non-approval of the active substance flufenoxuron