Great Expectations

Title page of Vol. I of first edition, July 1861 | |

| Author | Charles Dickens |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Novel, Bildungsroman |

| Set in | Kent and London, early to mid-19th century |

| Published | Serialised 1860–61; book form 1861 |

| Publisher | Chapman & Hall |

| Publication place | England |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 544 (first edition 1861) |

| OCLC | 1269308353 |

| 823.83 | |

| LC Class | PR4560 .A1 |

| Preceded by | A Tale of Two Cities |

| Followed by | Our Mutual Friend |

| Text | Great Expectations at Wikisource |

Great Expectations is the thirteenth novel by English author Charles Dickens and his penultimate completed novel. The novel is a bildungsroman and depicts the education of an orphan nicknamed Pip. It is Dickens' second novel, after David Copperfield, to be fully narrated in the first person.[N 1] The novel was first published as a serial in Dickens's weekly periodical All the Year Round, from 1 December 1860 to August 1861.[1] In October 1861, Chapman & Hall published the novel in three volumes.[2][3][4]

The novel is set in Kent and London in the early to mid-19th century[5] and contains some of Dickens's most celebrated scenes, starting in a graveyard, where the young Pip is accosted by the escaped convict Abel Magwitch. Great Expectations is full of extreme imagery—poverty, prison ships and chains, and fights to the death—and has a colourful cast of characters who have entered popular culture. These include the eccentric Miss Havisham, the beautiful but cold Estella, and Joe Gargery, the unsophisticated and kind blacksmith. Dickens's themes include wealth and poverty, love and rejection, and the eventual triumph of good over evil. Great Expectations, which is popular with both readers and literary critics,[6][7] has been translated into many languages and adapted numerous times into various media.

The novel was very widely praised.[6] Although Dickens's contemporary Thomas Carlyle referred to it disparagingly as "that Pip nonsense", he nevertheless reacted to each fresh instalment with "roars of laughter".[8] Later, George Bernard Shaw praised the novel, describing it as "all of one piece and consistently truthful".[9] During the serial publication, Dickens was pleased with public response to Great Expectations and its sales;[10] when the plot first formed in his mind, he called it "a very fine, new and grotesque idea".[11]

In the 21st century, the novel retains good standing among literary critics[12] and in 2003 it was ranked 17th on the BBC's The Big Read poll.[13]

Plot summary

[edit]The book includes three "stages" of Pip's expectations.

First stage

[edit]Philip "Pip" Pirrip is a seven-year-old orphan who lives with his hot-tempered older sister and her kindly blacksmith husband Joe Gargery on the coastal marshes of Kent. On Christmas Eve 1812,[14] Pip visits the graves of his parents and siblings. There, he unexpectedly encounters an escaped convict who threatens to kill him if he does not bring back food and tools. Pip steals a file from among Joe's tools and a pie and brandy that were meant for Christmas dinner, which he delivers to the convict.

That evening, Pip's sister is about to look for the missing pie when soldiers arrive and ask Joe to mend some shackles. Joe and Pip accompany them into the marshes to recapture the convict, who is fighting with another escaped convict. The first convict confesses to stealing food, clearing Pip.[15]

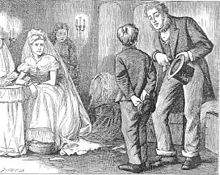

A few years later, Miss Havisham, a wealthy and reclusive spinster who lives in dilapidated Satis House wearing her old wedding dress after having been jilted at the altar, asks Mr Pumblechook, a relative of the Gargerys, to find a boy to visit her. Pip visits Miss Havisham and falls in love with Estella, her adopted daughter. Estella is aloof and hostile to Pip, which Miss Havisham encourages. During one visit, another boy picks a fistfight with Pip, where Pip easily gains the upper hand. Estella watches, and allows Pip to kiss her afterwards. Pip visits Miss Havisham regularly, until he is old enough to learn a trade.[16]

Joe accompanies Pip for the last visit to Miss Havisham, at which she gives Pip money to become an apprentice blacksmith. Joe's surly assistant, Dolge Orlick, is envious of Pip and dislikes Mrs. Joe. Orlick also complains when Joe says he needs to take Pip somewhere midday, thinking this is another sign of favoritism, of which Joe assures him he can quit work for the day. When Pip and Joe are away from the house, Joe's wife is brutally attacked, leaving her unable to speak or do her work. When Pip sees a leg iron was the weapon used in the attack, he becomes worried believing that it was the same leg iron he helped liberate the convict from. Now bedridden, Mrs. Joe is unable to be as "rampaging" towards Pip as before the attack. Pip's former schoolmate Biddy joins the household to help with her care.[17]

Four years into Pip's apprenticeship, Mr Jaggers, a lawyer, informs him that he has been provided with money from an anonymous patron, allowing him to become a gentleman. Presuming that Miss Havisham is his benefactress, Pip visits her before leaving for London.[18]

Second stage

[edit]Pip's first experience with urban England is a shock, for London is not the "soft white city" Pip imagined, but a place of heavy litter and filth. Pip moves into Barnard's Inn with Herbert Pocket, the son of his tutor, Matthew Pocket, who is Miss Havisham's cousin. Pip realizes Herbert is the boy he fought with years ago. Herbert tells Pip how Miss Havisham was defrauded and deserted by her fiancé. Pip meets fellow pupils, Bentley Drummle, a brute of a man from a wealthy noble family, and Startop, who is a more agreeable colleague. Jaggers disburses the money Pip needs.[19] During a visit, Pip meets Jaggers's housekeeper Molly, a former convict.

When Joe visits Pip at Barnard's Inn, Pip is ashamed to be seen with him. Joe relays a message from Miss Havisham that Estella will be visiting her. Pip returns there to meet Estella and is encouraged by Miss Havisham, but he avoids visiting Joe. He is disquieted to see Orlick now in service to Miss Havisham. He mentions his misgivings to Jaggers, who promises Orlick's dismissal. Back in London, Pip and Herbert exchange their romantic secrets: Pip adores Estella and Herbert is engaged to Clara. Pip meets Estella when she is sent to Richmond to be introduced into society.[20]

Pip and Herbert build up debts. Mrs Joe dies and Pip returns to his village for her funeral. Pip's income is fixed at £500 (equivalent to £53,000 in 2023) per annum when he comes of age at 21. With the help of Jaggers' clerk, John Wemmick, Pip plans to help advance Herbert's future prospects by anonymously securing him a position with the shipbroker, Clarriker's. Pip takes Estella to Satis House, where she and Miss Havisham quarrel over Estella's coldness. In London, Drummle outrages Pip by proposing a toast to Estella. Later, at an Assembly Ball in Richmond, Pip witnesses Estella meeting Drummle and warns her about him; she replies that she has no qualms about entrapping him.[21]

A week after his 23rd birthday, Pip learns that his benefactor is the convict he encountered in the churchyard, Abel Magwitch, who had been transported to New South Wales after being captured. He has become wealthy after gaining his freedom there, but cannot return to England on pain of death. However, he returns to see Pip, who was the motivation for all his success.

Third stage

[edit]A shocked Pip stops taking Magwitch's money, but devises a plan with Herbert to help him escape from England.[22] Magwitch shares his past with Pip, and reveals that the escaped convict whom he fought in the churchyard was Compeyson, the fraudster who had deserted Miss Havisham.[23]

Pip returns to Satis House to visit Estella and meets Drummle, who has also come to see her and now has Orlick as his servant. Pip confronts Miss Havisham for misleading him about his benefactor, but she says she did it to annoy her relatives. Pip declares his love to Estella, who coldly tells him that she plans on marrying Drummle. A heartbroken Pip returns to London, where Wemmick warns him that Compeyson is looking for him.[24]

At Jaggers's house at dinner, Wemmick tells Pip how Jaggers acquired his maidservant, Molly, rescuing her from the gallows when she was accused of murder.[25] A remorseful Miss Havisham tells Pip how she raised Estella to be unfeeling and heartless ever since Jaggers brought her in as an infant with no information on her parentage. She also tells Pip that Estella is now married. She gives Pip money to pay for Herbert's position at Clarriker's, and asks for his forgiveness. As Pip is about to leave, Miss Havisham's dress catches fire, and Pip injures himself in an unsuccessful attempt to save her. Realising that Estella is the daughter of Molly and Magwitch, Pip is discouraged by Jaggers from acting on his suspicions.[26]

A few days before Magwitch's planned escape, Pip is tricked by an anonymous letter into going to a sluice-house near his old home, where he is seized by Orlick, who intends to murder him and freely admits to injuring Pip's sister. As Pip is about to be struck with a hammer, Herbert and Startop arrive and save him. The three of them pick up Magwitch to row him to the steamboat for Hamburg, but they are met by a police boat carrying Compeyson, who has offered to identify Magwitch. Magwitch seizes Compeyson, and they fight in the river. Seriously injured, Magwitch is taken by the police. Compeyson's body is found later.[27]

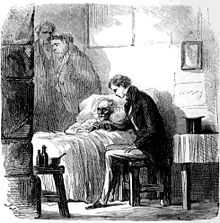

Aware that Magwitch's fortune will go to the Crown after his trial, Pip visits a dying Magwitch in the prison hospital, and eventually tells him that his daughter Estella is alive. Herbert, who is preparing to move to Cairo, Egypt to manage Clarriker's office, offers Pip a position there. After Herbert's departure, Pip falls ill in his room, and faces arrest for debt. However, Joe nurses Pip back to health and pays off the debt. After recovering, Pip then returns to propose to Biddy, only to find that she has married Joe. Pip apologises to Joe, vows to repay him and leaves for Cairo. There he moves in with Herbert and Clara, and eventually advances to become third in the company. Only then does Herbert learn that Pip paid for his position in the firm.[28]

After working for eleven years in Egypt, Pip returns to England and visits Joe, Biddy, and their son, Pip Jr. Then, in the ruins of Satis House, he meets the widowed Estella, who asks Pip to forgive her, assuring him that her misfortune, and her abusive marriage to Drummle until his death, has opened her heart. As Pip takes Estella's hand, and they leave the moonlit ruins, he sees "no shadow of another parting from her".[29]

Characters

[edit]Pip and his family

[edit]- Philip Pirrip, nicknamed Pip, an orphan and the protagonist and narrator of Great Expectations. In his childhood, Pip dreamed of becoming a blacksmith like his kind brother-in-law, Joe Gargery. At Satis House, aged about 8, he meets and falls in love with Estella, and tells Biddy that he wants to become a gentleman. As a result of Magwitch's anonymous patronage, Pip lives in London after learning the blacksmith trade, and becomes a gentleman. Pip assumes his benefactor is Miss Havisham; the discovery that his true benefactor is a convict shocks him. Pip, at the end of the story, is united with Estella.

- Joe Gargery, Pip's brother-in-law, and his first father figure. He is a blacksmith who is always kind to Pip and the only person with whom Pip is always honest. Joe is disappointed when Pip decides to leave his home to live in London to become a gentleman rather than be a blacksmith in business with Joe. He is a strong man who bears the shortcomings of those closest to him.

- Mrs Joe Gargery, Pip's hot-tempered adult sister, Georgiana Maria, called Mrs Joe, is more than 20 years older than Pip. She brings him up after their parents' death. She does the work of the household but too often loses her temper and beats her family. Orlick, her husband's journeyman, attacks her during a botched burglary, and she is left disabled until her death.

- Mr Pumblechook, Joe Gargery's uncle, an officious bachelor and corn merchant. While not knowing how to deal with a growing boy, he tells Mrs Joe, as she is known, how noble she is to bring up Pip. As the person who first connected Pip to Miss Havisham, he claims to have been the original architect of Pip's expectations. Pip dislikes Mr Pumblechook for his pompous, unfounded claims. When Pip stands up to him in a public place, after those expectations are dashed, Mr Pumblechook turns those listening to the conversation against Pip.

Miss Havisham and her family

[edit]- Miss Havisham, a wealthy spinster who takes Pip on as a companion for herself and her adopted daughter, Estella. Havisham is a wealthy, eccentric woman who has worn her wedding dress and one shoe since the day that she was jilted at the altar by her fiancé. Her house is unchanged as well. She hates all men, and plots to wreak a twisted revenge by teaching Estella to torment and spurn men, including Pip, who loves her. Miss Havisham is later overcome with remorse for ruining both Estella's and Pip's chances for happiness. Shortly after confessing her plotting to Pip and begging for his forgiveness, she is badly burned when her dress accidentally catches fire. In a later chapter Pip learns from Joe that she is dead.

- Estella, Miss Havisham's adopted daughter, whom Pip pursues. She is a beautiful girl and grows more beautiful after her schooling in France. Estella represents the life of wealth and culture for which Pip strives. Since Miss Havisham has sabotaged Estella's ability to love, Estella cannot return Pip's passion. She warns Pip of this repeatedly, but he will not or cannot believe her. Estella does not know that she is the daughter of Molly, Jaggers's housekeeper, and the convict Abel Magwitch, given up for adoption to Miss Havisham after her mother was arrested for murder. In marrying Bentley Drummle, she rebels against Miss Havisham's plan to have her break a husband's heart, as Drummle is not interested in Estella but simply in the Havisham fortune.

- Matthew Pocket, Miss Havisham's cousin. He is the patriarch of the Pocket family, but unlike her other relatives, he is not greedy for Havisham's wealth. Matthew Pocket tutors young gentlemen, such as Bentley Drummle, Startop, Pip and his own son Herbert.

- Herbert Pocket, the son of Matthew Pocket, who was invited like Pip to visit Miss Havisham, but she did not take to him. Pip first meets Herbert as a "pale young gentleman" who challenges Pip to a fistfight at Miss Havisham's house when both are children. He later becomes Pip's friend, tutoring him in the "gentlemanly" arts and sharing his rooms with Pip in London.

- Camilla, one of the sisters of Matthew Pocket, and therefore a cousin of Miss Havisham, she is an obsequious, detestable woman who is intent on pleasing Miss Havisham to get her money.

- Cousin Raymond, a relative of Miss Havisham who is only interested in her money. He is married to Camilla.

- Georgiana, a relative of Miss Havisham who is only interested in her money. She is one of the many relatives who hang around Miss Havisham "like flies" for her wealth.

- Sarah Pocket, the sister of Matthew Pocket, relative of Miss Havisham. She is often at Satis House. She is described as "a dry, brown corrugated old woman, with a small face that might have been made out of walnut shells, and a large mouth like a cat's without the whiskers".

From Pip's youth

[edit]- Abel Magwitch, the convict, who escapes from a prison ship, whom Pip treats kindly, and who becomes Pip's benefactor. Magwitch uses the aliases "Provis" and "Mr. Campbell" when he returns to England from exile in Australia. He is a lesser actor in crime with Compeyson, but gains a longer sentence in an apparent application of justice by social class.

- Mr and Mrs Hubble, simple folk who think they are more important than they really are. They live in Pip's village.

- Mr Wopsle, clerk of the church in Pip's village. He later gives up the church work and moves to London to pursue his ambition to be an actor, adopting the stage name "Mr Waldengarver". He sees the other convict in the audience of one of his performances, attended also by Pip.

- Biddy, Wopsle's second cousin and near Pip's age; she teaches in the evening school at her grandmother's home in Pip's village. Pip wants to learn more, so he asks her to teach him all she can. After helping Mrs Joe after the attack, Biddy opens her own school. A kind and intelligent but poor young woman, she is, like Pip and Estella, an orphan. She acts as Estella's foil. Orlick was attracted to her, but she did not want his attentions. Pip ignores her affections for him as he pursues Estella. Recovering from his own illness after the failed attempt to get Magwitch out of England, Pip returns to claim Biddy as his bride, arriving in the village just after she marries Joe Gargery. Biddy and Joe later have two children, one named after Pip. In the ending to the novel discarded by Dickens but revived by students of the novel's development, Estella mistakes the boy as Pip's child.

Mr Jaggers and his circle

[edit]

- Mr Jaggers, prominent London lawyer who represents the interests of diverse clients, both criminal and civil. He represents Pip's benefactor and Miss Havisham as well. By the end of the story, his law practice links many of the characters.

- John Wemmick, Jaggers's clerk, who is Pip's chief go-between with Jaggers and looks after Pip in London. Wemmick lives with his father, "The Aged Parent", in a small replica of a castle, complete with a drawbridge and moat, in Walworth.

- Molly, Mr Jaggers's maidservant whom Jaggers saved from the gallows for murder. She is revealed to be Magwitch's estranged wife and Estella's mother.

Antagonists

[edit]- Compeyson, a convict who escapes the prison ship after Magwitch, who beats him up ashore. He is Magwitch's enemy. A professional swindler, he was engaged to marry Miss Havisham, but he was in league with her half-brother, Arthur Havisham, to defraud Miss Havisham of part of her fortune. Later he sets up Magwitch to take the fall for another swindle. He works with the police when he learns Abel Magwitch is in London, fearing Magwitch after their first escapes years earlier. When the police boat encounters the one carrying Magwitch, the two grapple, and Compeyson drowns in the Thames.

- Arthur Havisham, younger half brother of Miss Havisham, who plots with Compeyson to swindle her.

- Dolge Orlick, journeyman blacksmith at Joe Gargery's forge. Strong, rude and sullen, he is as churlish as Joe is gentle and kind. He ends up in a fistfight with Joe over Mrs Gargery's taunting, and Joe easily defeats him. This sets in motion an escalating chain of events that leads him secretly to assault Mrs Gargery and to try to kill her brother Pip. The police ultimately arrest him for housebreaking into Uncle Pumblechook's, where he is later jailed.

- Bentley Drummle, a coarse, unintelligent young man from a wealthy noble family being "the next heir but one to a baronetcy".[30] Pip meets him at Mr Pocket's house, as Drummle is also to be trained in gentlemanly skills. Drummle is hostile to Pip and everyone else. He is a rival for Estella's attentions and eventually marries her and is said to abuse her. He dies from an accident following his mistreatment of a horse.

Other characters

[edit]- Clara Barley, a very poor girl living with her gout-ridden father. She marries Herbert Pocket near the novel's end. She dislikes Pip at first because of his spendthrift ways. After she marries Herbert, they invite Pip to live with them.

- Miss Skiffins occasionally visits Wemmick's house and wears green gloves. She changes those green gloves for white ones when she marries Wemmick.

- Startop, like Bentley Drummle, is Pip's fellow student, but unlike Drummle, he is kind. He assists Pip and Herbert in their efforts to help Magwitch escape.

The creative process

[edit]

As Dickens began writing Great Expectations, he undertook a series of hugely popular and remunerative reading tours. His domestic life had, however, disintegrated in the late 1850s and he had separated from his wife, Catherine Dickens, and was having a secret affair with the much younger Ellen Ternan. It has been suggested that the icy teasing of the character Estella is based on Ellen Ternan's reluctance to become Dickens's mistress.[31]

Beginning

[edit]In his Book of Memoranda, begun in 1855, Dickens wrote names for possible characters: Magwitch, Provis, Clarriker, Compey, Pumblechook, Orlick, Gargery, Wopsle, Skiffins, some of which became familiar in Great Expectations. There is also a reference to a "knowing man", a possible sketch of Bentley Drummle.[32] Another evokes a house full of "Toadies and Humbugs", foreshadowing the visitors to Satis House in chapter 11.[32][33] Margaret Cardwell discovered the "premonition" of Great Expectations from a 25 September 1855 letter from Dickens to W. H. Wills, in which Dickens speaks of recycling an "odd idea" from the Christmas special "A House to Let" and "the pivot round which my next book shall revolve".[34][35] The "odd idea" concerns an individual who "retires to an old lonely house…resolved to shut out the world and hold no communion with it".[34]

In an 8 August 1860 letter to Thomas Carlyle, Dickens reported his agitation whenever he prepared a new book.[32] A month later, in a letter to John Forster, Dickens announced that he just had a new idea.[36]

Publication in All the Year Round

[edit]

Dickens was pleased with the idea, calling it "such a very fine, new and grotesque idea" in a letter to Forster.[11] He planned to write "a little piece", a "grotesque tragi-comic conception", about a young hero who befriends an escaped convict, who then makes a fortune in Australia and anonymously bequeaths his property to the hero. In the end, the hero loses the money because it is forfeited to the Crown. In his biography of Dickens, Forster wrote that in the early idea "was the germ of Pip and Magwitch, which at first he intended to make the groundwork of a tale in the old twenty-number form".[37] Dickens presented the relationship between Pip and Magwitch pivotal to Great Expectations but without Miss Havisham, Estella, or other characters he later created.

As the idea and Dickens's ambition grew, he began writing. However, in September, the weekly All the Year Round saw its sales fall, and its flagship publication, A Day's Ride by Charles Lever, lost favour with the public. Dickens "called a council of war", and believed that to save the situation, "the one thing to be done was for [him] to strike in".[38] The "very fine, new and grotesque idea" became the magazine's new support: weeklies, five hundred pages, just over one year (1860–1861), thirty-six episodes, starting 1 December. The magazine continued to publish Lever's novel until its completion on 23 March 1861,[39] but it became secondary to Great Expectations. Immediately, sales resumed, and critics responded positively, as exemplified by The Times's praise: "Great Expectations is not, indeed, [Dickens's] best work, but it is to be ranked among his happiest".[40]

Dickens, whose health was not the best, felt "The planning from week to week was unimaginably difficult" but persevered.[39] He thought he had found "a good name", decided to use the first person "throughout", and thought the beginning was "excessively droll": "I have put a child and a good-natured foolish man, in relations that seem to me very funny".[41] Four weekly episodes were "ground off the wheel" in October 1860,[42] and apart from one reference to the "bondage" of his heavy task,[43] the months passed without the anguished cries that usually accompanied the writing of his novels.[39] He did not even use the Number Plans or Mems;[N 2] he had only a few notes on the characters' ages, the tide ranges for chapter 54, and the draft of an ending. In late December, Dickens wrote to Mary Boyle that "Great Expectations [is] a very great success and universally liked".[10]

Dickens gave six readings from 14 March to 18 April 1861, and in May, Dickens took a few days' holiday in Dover. On the eve of his departure, he took some friends and family members for a trip by boat from Blackwall to Southend-on-Sea. Ostensibly for pleasure, the mini-cruise was actually a working session for Dickens to examine banks of the river in preparation for the chapter devoted to Magwitch's attempt to escape.[37] Dickens then revised Herbert Pocket's appearance, no doubt, asserts Margaret Cardwell, to look more like his son Charley.[44] On 11 June 1861, Dickens wrote to Macready that Great Expectations had been completed and on 15 June, asked the editor to prepare the novel for publication.[39]

Revised ending

[edit]Following comments by Edward Bulwer-Lytton that the ending was too sad, Dickens rewrote it prior to publication. The ending set aside by Dickens has Pip, who is still single, briefly see Estella in London; after becoming Bentley Drummle's widow, she has remarried.[39][45] It appealed to Dickens due to its originality: "[the] winding up will be away from all such things as they conventionally go".[39][46] Dickens revised the ending for publication so that Pip meets Estella in the ruins of Satis House, she is a widow and he is single. His changes at the conclusion of the novel did not quite end either with the final weekly part or the first bound edition, because Dickens further changed the last sentence in the amended 1868 version from "I could see the shadow of no parting from her"[39] to "I saw no shadow of another parting from her".[47] As Pip uses litotes, "no shadow of another parting", it is ambiguous whether Pip and Estella marry or Pip remains single. Angus Calder, writing for an edition in the Penguin English Library, believed the less definite phrasing of the amended 1868 version perhaps hinted at a buried meaning: 'at this happy moment, I did not see the shadow of our subsequent parting looming over us.'[48]

In a letter to Forster, Dickens explained his decision to alter the draft ending: "You will be surprised to hear that I have changed the end of Great Expectations from and after Pip's return to Joe's ... Bulwer, who has been, as I think you know, extraordinarily taken with the book, strongly urged it upon me, after reading the proofs, and supported his views with such good reasons that I have resolved to make the change. I have put in as pretty a little piece of writing as I could, and I have no doubt the story will be more acceptable through the alteration".[49][50]

This discussion between Dickens, Bulwer-Lytton and Forster has provided the basis for much discussion on Dickens's underlying views for this famous novel. Earle Davis, in his 1963 study of Dickens, wrote that "it would be an inadequate moral point to deny Pip any reward after he had shown a growth of character," and that "Eleven years might change Estella too".[51] John Forster felt that the original ending was "more consistent" and "more natural"[52][53] but noted the new ending's popularity.[54] George Gissing called that revision "a strange thing, indeed, to befall Dickens" and felt that Great Expectations would have been perfect had Dickens not altered the ending in deference to Bulwer-Lytton.[N 3][55]

In contrast, John Hillis-Miller stated that Dickens's personality was so assertive that Bulwer-Lytton had little influence, and welcomed the revision: "The mists of infatuation have cleared away, [Estella and Pip] can be joined".[56] Earl Davis notes that G. B. Shaw published the novel in 1937 for The Limited Editions Club with the first ending and that The Rinehart Edition of 1979 presents both endings.[54][57][58]

George Orwell wrote, "Psychologically the latter part of Great Expectations is about the best thing Dickens ever did," but, like John Forster and several early 20th century writers, including George Bernard Shaw, felt that the original ending was more consistent with the draft, as well as the natural working out of the tale.[59] Modern literary criticism is split over the matter.

Publication history

[edit]In periodicals

[edit]Dickens and Wills co-owned All the Year Round, one 75%, the other 25%. Since Dickens was his own publisher, he did not require a contract for his own works.[60] Although intended for weekly publication, Great Expectations was divided into nine monthly sections, with new pagination for each.[53] Harper's Weekly published the novel from 24 November 1860 to 5 August 1861 in the US and All the Year Round published it from 1 December 1860 to 3 August 1861 in the UK. Harper's paid £1,000 (equivalent to £119,000 in 2023) for publication rights. Dickens welcomed a contract with Tauchnitz 4 January 1861 for publication in English for the European continent.

Publications in Harper's Weekly were accompanied by forty illustrations by John McLenan;[61] however, this is the only Dickens work published in All the Year Round without illustrations.

Editions

[edit]Robert L Patten identifies four American editions in 1861 and sees the proliferation of publications in Europe and across the Atlantic as "extraordinary testimony" to Great Expectations's popularity.[62] Chapman and Hall published the first edition in three volumes in 1861,[2][3][4] five subsequent reprints between 6 July and 30 October, and a one-volume edition in 1862. The "bargain" edition was published in 1862, the Library Edition in 1864, and the Charles Dickens edition in 1868. To this list, Paul Schlicke adds "two meticulous scholarly editions", one Clarendon Press published in 1993 with an introduction by Margaret Cardwell[63] and another with an introduction by Edgar Rosenberg, published by Norton in 1999.[53] The novel was published with one ending (visible in the four online editions listed in the External links at the end of this article). In some 20th century editions, the novel ends as originally published in 1867, and in an afterword, the ending Dickens did not publish, along with a brief story of how a friend persuaded him to a happier ending for Pip, is presented to the reader (for example, 1987 audio edition by Recorded Books[64]).

In 1862, Marcus Stone,[65] son of Dickens's old friend, the painter Frank Stone, was invited to create eight woodcuts for the Library Edition. According to Paul Schlicke, these illustrations are mediocre yet were included in the Charles Dickens edition, and Stone created illustrations for Dickens's subsequent novel, Our Mutual Friend.[53] Later, Henry Mathew Brock also illustrated Great Expectations and a 1935 edition of A Christmas Carol,[66] along with other artists, such as John McLenan,[67] F. A. Fraser,[68] and Harry Furniss.[69]

First edition publication schedule

[edit]| Part | Date | Chapters |

|---|---|---|

| 1–5 | 1, 8, 15, 22, 29 December 1860 | 1–8 |

| 6–9 | 5, 12, 19, 26 January 1861 | 9–15 |

| 10–12 | 2, 9, 23 February 1861 | 16–21 |

| 13–17 | 2, 9, 16, 23, 30 March 1861 | 22–29 |

| 18–21 | 6, 13, 20, 27 April 1861 | 30–37 |

| 22–25 | 4, 11, 18, 25 May 1861 | 38–42 |

| 26–30 | 1, 8 15, 22, 29 June 1861 | 43–52 |

| 31–34 | 6, 13, 20, 27 July 1861 | 53–57 |

| 35 | 3 August 1861 | 58–59 |

Reception

[edit]Robert L. Patten estimates that All the Year Round sold 100,000 copies of Great Expectations each week, and Mudie, the largest circulating library, which purchased about 1,400 copies, stated that at least 30 people read each copy.[70] Aside from the dramatic plot, the Dickensian humour also appealed to readers. Dickens wrote to Forster in October 1860 that "You will not have to complain of the want of humour as in the Tale of Two Cities,"[71] an opinion Forster supports, finding that "Dickens's humour, not less than his creative power, was at its best in this book".[37][72] Moreover, according to Paul Schlicke, readers found the best of Dickens's older and newer writing styles.[6]

Overall, Great Expectations was widely praised,[6] although not all reviews were favourable, however; Margaret Oliphant's review, published May 1862 in Blackwood's Magazine, vilified the novel. Critics in the 19th and 20th centuries hailed it as one of Dickens's greatest successes although often for conflicting reasons: G. K. Chesterton admired the novel's optimism; Edmund Wilson its pessimism; Humphry House in 1941 emphasized its social context. In 1974, Jerome H. Buckley saw it as a Bildungsroman, writing a chapter on Dickens and two of his major protagonists (David Copperfield and Pip) in his 1974 book on the Bildungsroman in Victorian writing.[73] John Hillis Miller wrote in 1958 that Pip is the archetype of all Dickensian heroes.[7] In 1970, Q. D. Leavis suggested "How We Must Read Great Expectations".[74] In 1984, Peter Brooks, in the wake of Jacques Derrida, offered a deconstructionist reading.[75] The most profound analyst, according to Paul Schlicke, is probably Julian Moynahan, who, in a 1964 essay surveying the hero's guilt, made Orlick "Pip's double, alter ego and dark mirror image". Schlicke also names Anny Sadrin's extensive 1988 study as the "most distinguished".[76]

In 2015, the BBC polled book critics outside the UK about novels by British authors; they ranked Great Expectations fourth on the list of the 100 Greatest British Novels.[12] Earlier, in its 2003 poll The Big Read concerning the reading taste of the British public, Great Expectations was voted 17th out of the top 100 novels chosen by survey participants.[13]

Background

[edit]Great Expectations's single most obvious literary predecessor is Dickens's earlier first-person protagonist-narrated David Copperfield. The two novels trace the psychological and moral development of a young boy to maturity, his transition from a rural environment to the London metropolis, the vicissitudes of his emotional development, and the exhibition of his hopes and youthful dreams and their metamorphosis, through a rich and complex first person narrative.[77] Dickens was conscious of this similarity and, before undertaking his new manuscript, reread David Copperfield to avoid repetition.[41]

The two books both detail homecoming. Although David Copperfield is based on some of Dickens's personal experiences, Great Expectations provides, according to Paul Schlicke, "the more spiritual and intimate autobiography".[78] Even though several elements hint at the setting—Miss Havisham, partly inspired by a Parisian duchess, whose residence was always closed and in darkness, surrounded by "a dead green vegetable sea", recalling Satis House,[79][80] aspects of Restoration House that inspired Satis House,[81][82][83][84] and the nearby countryside bordering Chatham and Rochester. No place name is mentioned,[N 4] nor a specific time period, which is generally indicated by, among other elements, older coaches, the title "His Majesty" in reference to George III, and the old London Bridge prior to the 1824–1831 reconstruction.[85]

The theme of homecoming reflects events in Dickens's life, several years prior to the publication of Great Expectations. In 1856, he bought Gad's Hill Place in Higham, Kent, which he had dreamed of living in as a child, and moved there from faraway London two years later. In 1858, in a painful marriage breakdown, he separated from Catherine Dickens, his wife of twenty-three years. The separation alienated him from some of his closest friends, such as Mark Lemon. He quarrelled with Bradbury and Evans, who had published his novels for fifteen years. In early September 1860, in a field behind Gad's Hill, Dickens burned almost all of his correspondence, sparing only letters on business matters.[86][87] He stopped publishing the weekly Household Words at the summit of its popularity and replaced it with All the Year Round.[78]

The Uncommercial Traveller, short stories, and other texts Dickens began publishing in his new weekly in 1859 reflect his nostalgia, as seen in "Dullborough Town" and "Nurses' Stories". According to Paul Schlicke, "it is hardly surprising that the novel Dickens wrote at this time was a return to roots, set in the part of England in which he grew up, and in which he had recently resettled".[78]

Margaret Cardwell draws attention to Chops the Dwarf from Dickens's 1858 Christmas story "Going into Society", who, as the future Pip does, entertains the illusion of inheriting a fortune and becomes disappointed upon achieving his social ambitions.[88] In another vein, Harry Stone thinks that Gothic and magical aspects of Great Expectations were partly inspired by Charles Mathews's At Home, which was presented in detail in Household Words and its monthly supplement Household Narrative. Stone also asserts that The Lazy Tour of Two Idle Apprentices, written in collaboration with Wilkie Collins after their walking tour of Cumberland during September 1857 and published in Household Words from 3 to 31 October of the same year, presents certain strange locations and a passionate love, foreshadowing Great Expectations.[89]

Beyond its biographical and literary aspects, Great Expectations appears, according to Robin Gilmour, as "a representative fable of the age".[90] Dickens was aware that the novel "speaks" to a generation applying, at most, the principle of "self help" which was believed to have increased the order of daily life. That the hero Pip aspires to improve, not through snobbery, but through the Victorian conviction of education, social refinement, and materialism, was seen as a noble and worthy goal. However, by tracing the origins of Pip's "great expectations" to crime, deceit and even banishment to the colonies, Dickens unfavourably compares the new generation to the previous one of Joe Gargery, which Dickens portrays as less sophisticated but especially rooted in sound values, presenting an oblique criticism of his time.[90]

Structure

[edit]The narrative structure of Great Expectations is influenced by the fact that it was first published as weekly episodes in a periodical. This required short chapters, centred on a single subject, and an almost mathematical structure.[91]

Chronology

[edit]Pip's story is told in three stages: his childhood and early youth in Kent, where he dreams of rising above his humble station; his time in London after receiving "great expectations"; and then finally his disillusionment on discovering the source of his fortune, followed by his slow realisation of the vanity of his false values.[92] These three stages are further divided into twelve parts of equal length. This symmetry contributes to the impression of completion, which has often been commented on. George Gissing, for example, when comparing Joe Gargery and Dan'l Peggotty (from David Copperfield), preferred the former, because he is a stronger character, who lives "in a world, not of melodrama, but of everyday cause and effect".[93] G. B. Shaw also commented on the novel's structure, describing it as "compactly perfect", and Algernon Swinburne stated, "The defects in it are as nearly imperceptible as spots on the sun or shadow on a sunlit sea".[94][95] A contributing factor is "the briskness of the narrative tone".[96]

Narrative flow

[edit]Further, beyond the chronological sequences and the weaving of several storylines into a tight plot, the sentimental setting and morality of the characters also create a pattern.[97] The narrative structure of Great Expectations has two main elements: firstly that of "foster parents", Miss Havisham, Magwitch, and Joe, and secondly that of "young people", Estella, Pip and Biddy. There is a further organizing element that can be labelled "Dangerous Lovers", which includes Compeyson, Bentley Drummle and Orlick. Pip is the centre of this web of love, rejection and hatred. Dickens contrasts this "dangerous love" with the relationship of Biddy and Joe, which grows from friendship to marriage.

This is "the general frame of the novel". The term "love" is generic, applying it to both Pip's true love for Estella and the feelings Estella has for Drummle, which are based on a desire for social advancement. Similarly, Estella rejects Magwitch because of her contempt for everything that appears below what she believes to be her social status.[98]

Great Expectations has an unhappy ending, since most characters suffer physically, psychologically or both, or die—often violently—while suffering. Happy resolutions remain elusive, while hate thrives. The only happy ending is Biddy and Joe's marriage and the birth of their two children, since the final reconciliations, except that between Pip and Magwitch, do not alter the general order. Though Pip extirpates the web of hatred, the first unpublished ending denies him happiness while Dickens's revised second ending, in the published novel, leaves his future uncertain.[99]

Orlick as Pip's double

[edit]Julian Moynahan argues that the reader can better understand Pip's personality through analysing his relationship with Orlick, the criminal laborer who works at Joe Gargery's forge, than by looking at his relationship with Magwitch.[100]

Following Moynahan, David Trotter[101] notes that Orlick is Pip's shadow. Co-workers in the forge, both find themselves at Miss Havisham's, where Pip enters and joins the company, while Orlick, attending the door, stays out. Pip considers Biddy a sister; Orlick has other plans for her; Pip is connected to Magwitch, Orlick to Magwitch's nemesis, Compeyson. Orlick also aspires to "great expectations" and resents Pip's ascension from the forge and the swamp to the glamour of Satis House, from which Orlick is excluded, along with London's dazzling society. Orlick is the cumbersome shadow Pip cannot remove.[101]

Then comes Pip's punishment, with Orlick's savage attack on Mrs Gargery. Thereafter Orlick vanishes, only to reappear in chapter 53 in a symbolic act, when he lures Pip into a locked, abandoned building in the marshes. Orlick has a score to settle before going on to the ultimate act, murder. However, Pip hampers Orlick, because of his privileged status, while Orlick remains a slave of his condition, solely responsible for Mrs Gargery's fate.[101][102]

Dickens also uses Pip's upper class counterpart, Bentley Drummle, "the double of a double", according to Trotter, in a similar way.[102] Like Orlick, Drummle is powerful, swarthy, unintelligible, hot-blooded, and lounges and lurks, biding his time. Estella rejects Pip for this rude, uncouth but well-born man, and ends Pip's hope. Finally the lives of both Orlick and Drummle end violently.[102]

Point of view

[edit]

Although the novel is written in first person, the reader knows—as an essential prerequisite—that Great Expectations is not an autobiography but a novel, a work of fiction with plot and characters, featuring a narrator-protagonist. In addition, Sylvère Monod notes that the treatment of the autobiography differs from David Copperfield, as Great Expectations does not draw from events in Dickens's life; "at most some traces of a broad psychological and moral introspection can be found".[103]

However, according to Paul Pickerel's analysis, Pip—as both narrator and protagonist—recounts with hindsight the story of the young boy he was, who did not know the world beyond a narrow geographic and familial environment. The novel's direction emerges from the confrontation between the two periods of time. At first, the novel presents a mistreated orphan, repeating situations from Oliver Twist and David Copperfield, but the trope is quickly overtaken. The theme manifests itself when Pip discovers the existence of a world beyond the marsh, the forge and the future Joe envisioned for him, the decisive moment when Miss Havisham and Estella enter his life.[104] This is a red herring, as the decay of Satis House and the strange lady within signals the fragility of an impasse. At this point, the reader knows more than the protagonist, creating dramatic irony that confers a superiority that the narrator shares.[105]

It is not until Magwitch's return, a plot twist that unites loosely connected plot elements and sets them into motion, that the protagonist's point of view joins those of the narrator and the reader.[106] In this context of progressive revelation, the sensational events at the novel's end serve to test the protagonist's point of view. Thus proceeds, in the words of A. E. Dyson, "The Immolations of Pip".[107]

Style

[edit]Some of the narrative devices that Dickens uses are caricature, comic speech mannerisms, intrigue, Gothic atmosphere, and a central character who gradually changes. Earl Davis notes the close network of the structure and balance of contrasts, and praises the first-person narration for providing a simplicity that is appropriate for the story while avoiding melodrama. Davis sees the symbolism attached to "great expectations"[vague] as reinforcing the novel's impact.[108]

Characterisation

[edit]Character leitmotiv

[edit]

Characters then become themes in themselves, almost a Wagnerian leitmotiv, whose attitudes are repeated at each of their appearances as a musical phrase signaling their entry.[109] For example, Jaggers constantly chews the same fingernail and washes his hands with scented soap, Orlick lurches his huge body, and Matthew Pocket always pulls at his hair. Seen by the narrator, their attitude is mechanical, like that of an automaton: in the general scheme, the gesture betrays the uneasiness of the unaccomplished or exasperated man, his betrayed hope, his unsatisfied life.[109] In this set, every character is orbited by "satellite" characters. Wemmick is Jaggers's copy at work, but has placed in Walworth a secret garden, a castle with a family of an elderly father and a middle-aged fiancée, where he happily devours buttered bread.[110] Wopsle plays the role of a poor Pip, kind of unsuccessful, but with his distraction, finally plays Hamlet in London, and Pumblechook does not hesitate to be the instrument of Pip's fortunes, then the mentor of his resurrection.[111]

Narrative technique

[edit]For Pip's redemption to be credible, Trotter writes, the words of the main character must sound right.[112] Christopher Ricks adds that Pip's frankness induces empathy, dramatics are avoided,[113] and his good actions are more eloquent than words. Dickens's subtle narrative technique is also shown when he has Pip confess that he arranged Herbert's partnership with Clarriker, has Miss Havisham finally see the true character of her cousin Matthew Pocket, and has Pocket refuse the money she offers him.[114] To this end, the narrative method subtly changes until, during the perilous journey down the Thames to remove Magwitch in chapter 54, the narrative point-of-view shifts from first person to the omniscient point of view. For the first time, Ricks writes, the "I" ceases to be Pip's thoughts and switches to the other characters, the focus, at once, turns outward, and this is mirrored in the imagery of the black waters tormented waves and eddies, which heaves with an anguish that encompasses the entire universe, the passengers, the docks, the river, the night.[114]

Romantic and symbolic realism

[edit]According to Paul Davis, while more realistic than its autobiographical predecessor written when novels like George Eliot's Adam Bede were in vogue, Great Expectations is in many ways a poetic work built around recurring symbolic images: the desolation of the marshes; the twilight; the chains of the house, the past, the painful memory; the fire; the hands that manipulate and control; the distant stars of desire; the river connecting past, present and future.[115]

Genre

[edit]Great Expectations contains a variety of literary genres, including the bildungsroman, gothic novel, crime novel, as well as comedy, melodrama and satire; and it belongs—like Wuthering Heights and the novels of Walter Scott—to the romance rather than realist tradition of the novel.[116]

Bildungsroman

[edit]Complex and multifaceted, Great Expectations is a Victorian bildungsroman, or initiatory tale, which focuses on a protagonist who matures over the course of the novel. Great Expectations describes Pip's initial frustration upon leaving home, followed by a long and difficult period that is punctuated with conflicts between his desires and the values of established order. During this time he re-evaluates his life and re-enters society on new foundations.[85]

However, the novel differs from the two preceding pseudo-autobiographies, David Copperfield and Bleak House (1852), (though the latter is only partially narrated in first-person), in that it also partakes of several sub-genres popular in Dickens's time.[117][85]

Comic novel

[edit]Great Expectations contains many comic scenes and eccentric personalities, integral parts to both the plot and the theme. Among the notable comic episodes are Pip's Christmas dinner in chapter 4, Wopsle's Hamlet performance in chapter 31, and Wemmick's marriage in chapter 55. Many of the characters have eccentricities: Jaggers with his punctilious lawyerly ways; the contrariness of his clerk, Wemmick, at work advising Pip to invest in "portable property", while in private living in a cottage converted into a castle; and the reclusive Miss Havisham in her decaying mansion, wearing her tattered bridal robes.[118]

Crime fiction

[edit]

Great Expectations incorporates elements of the new genre of crime fiction, which Dickens had already used in Oliver Twist (1837), and which was being developed by his friends Wilkie Collins and William Harrison Ainsworth. With its scenes of convicts, prison ships, and episodes of bloody violence, Dickens creates characters worthy of the Newgate school of fiction.[119]

Gothic novel

[edit]Great Expectations contains elements of the Gothic genre, especially Miss Havisham, the bride frozen in time, and the ruined Satis House filled with weeds and spiders.[85] Other characters linked to this genre include the aristocratic Bentley Drummle, because of his extreme cruelty; Pip himself, who spends his youth chasing a frozen beauty; the monstrous Orlick, who systematically attempts to murder his employers. Then there is the fight to the death between Compeyson and Magwitch, and the fire that ends up killing Miss Havisham, scenes dominated by horror, suspense, and the sensational.[117]

Silver-fork novel

[edit]Elements of the silver-fork novel are found in the character of Miss Havisham and her world, as well as Pip's illusions. This genre, which flourished in the 1820s and 1830s,[120] presents the flashy elegance and aesthetic frivolities found in high society. In some respects, Dickens conceived Great Expectations as an anti silver fork novel, attacking Charles Lever's novel A Day's Ride, publication of which began January 1860, in Household Words.[85][121] This can be seen in the way that Dickens satirises the pretensions and morals of Miss Havisham and her sycophants, including the Pockets (except Matthew), and Uncle Pumblechook.[85]

Historical novel

[edit]

Though Great Expectations is not obviously a historical novel, Dickens does emphasise differences between the time that the novel is set (c. 1812–46) and when it was written (1860–1).

Great Expectations begins around 1812 (the year of Dickens's birth), continues until around 1830–1835, and then jumps to around 1840–1845, during which the Great Western Railway was built.[85] Though readers today will not notice this, Dickens uses various things to emphasise the differences between 1861 and this earlier period. Among these details—that contemporary readers would have recognised—are the one pound note (in chapter 10) that the Bank Notes Act 1826 had removed from circulation;[122] likewise, the death penalty for deported felons who returned to Britain was abolished in 1835. The gallows erected in the swamps, designed to display a rotting corpse, had disappeared by 1832, and George III, the monarch mentioned at the beginning, died in 1820, when Pip would have been seven or eight.

Miss Havisham paid Joe 25 guineas, gold coins, when Pip was to begin his apprenticeship (in chapter 13); guinea coins were slowly going out of circulation after the last new ones were struck with the face of George III in 1799. This also marks the historical period, as the one pound note was the official currency at the time of the novel's publication. Dickens placed the epilogue 11 years after Magwitch's death, which seems to be the time limit of the reported facts. Collectively, the details suggest that Dickens identified with the main character. If Pip is around 23 toward the middle of the novel and 34 at its end, he is roughly modeled after his creator who turned 34 in 1846.[85]

Themes

[edit]The title's "Expectations" refers to "a legacy to come",[123] and thus immediately announces that money, or more specifically wealth plays an important part in the novel.[7] Some other major themes are crime, social class, including both gentility, and social alienation, imperialism and ambition. The novel is also concerned with questions relating to conscience and moral regeneration, as well as redemption through love.

Pip's name

[edit]Dickens famously created comic and telling names for his characters,[124] but in Great Expectations he goes further. The first sentence of the novel establishes that Pip's proper name is Philip Pirrip—the wording of his father's gravestone—which "my infant tongue could make of both names nothing longer or more explicit than Pip". The name Philip Pirrip (or Pirrip) is never again used in the novel. In Chapter 18, when he receives his expectation from an anonymous benefactor, the first condition attached to it is "that you always bear the name of Pip".

In Chapter 22, when Pip establishes his friendship with Herbert Pocket, he attempts to introduce himself as Philip. Herbert immediately rejects the name: "'I don't take to Philip,' said he, smiling, 'for it sounds like a moral boy out of the spelling-book'" and decides to refer to Pip exclusively as Handel: "'Would you mind Handel for a familiar name? There's a charming piece of music by Handel, called the Harmonious Blacksmith'". The only other place he is referred to as Philip is in Chapter 44, when he receives a letter addressed to "Philip Pip" from his friend Wemmick, which says "DON'T GO HOME".

Pip as social outcast

[edit]

A central theme here is of people living as social outcasts. The novel's opening setting emphasises this: the orphaned Pip lives in an isolated foggy environment next to a graveyard, dangerous swamps, and prison ships. Furthermore, "I was always treated as if I had insisted on being born in opposition to the dictates of reason, religion and morality".[125]

Pip feels excluded by society and this leads to his aggressive attitude towards it, as he tries to win his place within it through any means. Various other characters behave similarly—that is, the oppressed become the oppressors. Jaggers dominates Wemmick, who in turn dominates Jaggers's clients. Likewise, Magwitch uses Pip as an instrument of vengeance, as Miss Havisham uses Estella.[126]

However, Pip has hope despite his sense of exclusion[127] because he is convinced that divine providence owes him a place in society and that marriage to Estella is his destiny. Therefore, when fortune comes his way, Pip shows no surprise, because he believes that his value as a human being and his inherent nobility have been recognized. Thus, Pip accepts Pumblechook's flattery without blinking: "That boy is no common boy"[128] and the "May I? May I?" associated with handshakes.[129]

From Pip's hope comes his "uncontrollable, impossible love for Estella",[130] despite the humiliations to which she has subjected him. For Pip, winning a place in society also means winning Estella's heart.

Wealth

[edit]When the money secretly provided by Magwitch enables Pip to enter London society, two new related themes, wealth and gentility, are introduced.

As the novel's title implies, money is a theme of Great Expectations. Central to this is the idea that wealth is only acceptable to the ruling class if it comes from the labour of others.[131] Miss Havisham's wealth comes not from the sweat of her brow but from rent collected on properties she inherited from her father, a brewer. Her wealth is "pure", and her father's profession as a brewer does not contaminate it. Herbert states in chapter 22 that "while you cannot possibly be genteel and bake, you may be as genteel as never was and brew".[132] Because of her wealth, the old lady, despite her eccentricity, enjoys public esteem. She remains in a constant business relationship with her lawyer Jaggers and keeps a tight grip over her "court" of sycophants, so that, far from representing social exclusion, she is the very image of a powerful landed aristocracy that is frozen in the past and "embalmed in its own pride".[133]

On the other hand, Magwitch's wealth is socially unacceptable, firstly because he earned it, not through the efforts of others, but through his own hard work, and secondly because he was a convict, and he earned it in a penal colony. It is argued that the contrast with Miss Havisham's wealth is suggested symbolically. Thus Magwitch's money smells of sweat, and his money is greasy and crumpled: "two fat sweltering one-pound notes that seemed to have been on terms of the warmest intimacy with all the cattle market in the country",[134] while the coins Miss Havisham gives for Pip's "indentures" shine as if new. Further, it is argued Pip demonstrates his "good breeding", because when he discovers that he owes his transformation into a "gentleman" to such a contaminated windfall, he is repulsed.[133] A. O. J. Cockshut, however, has suggested that there is no difference between Magwitch's wealth and that of Miss Havisham.[135]

Trotter emphasizes the importance of Magwitch's greasy banknotes. Beyond Pip's emotional reaction the notes reveal that Dickens's views on social and economic progress have changed in the years prior to the publication of Great Expectations.[136] His novels and Household Words extensively reflect Dickens's views, and his efforts to contribute to social progress expanded in the 1840s. To illustrate his point, he cites Humphry House who, succinctly, writes that in Pickwick Papers, "a bad smell was a bad smell", whereas in Our Mutual Friend and Great Expectations, "it is a problem".[136][137]

At the time of The Great Exhibition of 1851, Dickens and Richard Henry Horne, an editor of Household Words, wrote an article comparing the British technology that created the Crystal Palace to the few artifacts exhibited by China: England represented an openness to worldwide trade and China isolationism. "To compare China and England is to compare Stoppage to Progress", they concluded. According to Trotter, this was a way to target the Tory government's return to protectionism, which they felt would make England the China of Europe. In fact, Household Words' 17 May 1856 issue championed international free trade, comparing the constant flow of money to the circulation of the blood.[138] In the 1850s, Dickens believed in "genuine" wealth, which critic Trotter compares to fresh banknotes, crisp to the touch, pure and odorless.[138]

With Great Expectations, Dickens's views about wealth have changed. However, though some sharp satire exists, no character in the novel has the role of the moralist that condemn Pip and his society. In fact, even Joe and Biddy themselves, paragons of good sense, are complicit, through their exaggerated innate humility, in Pip's social deviancy. Dickens's moral judgement is first made through the way that he contrasts characters: only a few characters keep to the straight and narrow path; Joe, whose values remain unchanged; Matthew Pocket whose pride renders him, to his family's astonishment, unable to flatter his rich relatives; Jaggers, who keeps a cool head and has no illusions about his clients; Biddy, who overcomes her shyness to, from time to time, bring order. The narrator-hero is left to draw the necessary conclusions: in the end, Pip finds the light and embarks on a path of moral regeneration.[139]

London as prison

[edit]

In London, neither wealth nor gentility brings happiness. Pip, the apprentice gentleman constantly bemoans his anxiety, his feelings of insecurity,[140] and multiple allusions to overwhelming chronic unease, to weariness, drown his enthusiasm (chapter 34).[141] Wealth, in effect, eludes his control: the more he spends, the deeper he goes into debt to satisfy new needs, which were just as futile as his old ones.

His unusual path to gentility has the opposite effect to what he expected: infinite opportunities become available, certainly, but will power, in proportion, fades and paralyses the soul. In the crowded metropolis, Pip grows disenchanted, disillusioned, and lonely. Alienated from his native Kent, he has lost the support provided by the village blacksmith. In London, he is powerless to join a community, not the Pocket family, much less Jaggers's circle. London has become Pip's prison and, like the convicts of his youth, he is bound in chains: "no Satis House can be built merely with money".[142][N 5]

Gentility

[edit]

The idea of "good breeding" and what makes for a "gentleman" other than money, in other words, "gentility", is a central theme of Great Expectations. The convict Magwitch covets it by proxy through Pip; Mrs Pocket dreams of acquiring it; it is also found in Pumblechook's sycophancy; it is even seen in Joe, when he stammers between "Pip" and "Sir" during his visit to London, and when Biddy's letters to Pip suddenly become reverent.

There are other characters who are associated with the idea of gentility like, for example, Miss Havisham's seducer, Compeyson, the scarred-face convict. While Compeyson is corrupt, even Magwitch does not forget he is a gentleman.[143] This also includes Estella, who ignores the fact that she is the daughter of Magwitch and another criminal.[133]

There are a couple of ways by which someone can acquire gentility, one being a title, another being family ties to the upper middle class. Mrs Pocket bases every aspiration on the fact that her grandfather failed to be knighted, while Pip hopes that Miss Havisham will eventually adopt him, as adoption, as evidenced by Estella, who behaves like a born and bred little lady, is acceptable.[144] But even more important, though not sufficient, are wealth and education. Pip knows that and endorses it, as he hears from Jaggers through Matthew Pocket: "I was not designed for any profession, and I should be well enough educated for my destiny if I could hold my own with the average of young men in prosperous circumstances."[145] But neither the educated Matthew Pocket, nor Jaggers, who has earned his status solely through his intellect, can aspire to gentility. Bentley Drummle, however, embodies the social ideal, so that Estella marries him without hesitation.[144]

Moral regeneration

[edit]Another theme of Great Expectations is that Pip can undergo "moral regeneration".

In chapter 39, the novel's turning point, Magwitch visits Pip to see the gentleman he has made, and once the convict has hidden in Herbert Pocket's room, Pip realises his situation:

For an hour or more, I remained too stunned to think; and it was not until I began to think, that I began fully to know how wrecked I was, and how the ship in which I had sailed was gone to pieces. Miss Havisham's intentions towards me, all a mere dream; Estella not designed for me ... But, sharpest and deepest pain of all—it was for the convict, guilty of I knew not what crimes, and liable to be taken out of those rooms where I sat thinking, and hanged at the Old Bailey door, that I had deserted Joe.[146]

To cope with his situation and his learning that he now needs Magwitch, a hunted, injured man who traded his life for Pip's. Pip can only rely on the power of love for Estella[147] Pip now goes through a number of different stages each of which, is accompanied by successive realisations about the vanity of the prior certainties.[148]

Pip's problem is more psychological and moral than social. Pip's climbing of the social ladder upon gaining wealth is followed by a corresponding degradation of his integrity. Thus after his first visit in Miss Havisham, the innocent young boy from the marshes, suddenly turns into a liar to dazzle his sister, Mrs Joe, and his Uncle Pumblechook with the tales of a carriage and veal chops.[140] More disturbing is his fascination with Satis House—where he is despised and even slapped, beset by ghostly visions, rejected by the Pockets—and the gradual growth of the mirage of London. The allure of wealth overpowers loyalty and gratitude, even conscience itself. This is evidenced by the urge to buy Joe's return, in chapter 27, Pip's haughty glance as Joe deciphers the alphabet, not to mention the condescending contempt he confesses to Biddy, copying Estella's behaviour toward him.[149]

Pip represents, as do those he mimics, the bankruptcy of the "idea of the gentleman", and becomes the sole beneficiary of vulgarity, inversely proportional to his mounting gentility.[150] In chapter 30, Dickens parodies the new disease that is corroding Pip's moral values through the character "Trabb's boy", who is the only one not to be fooled. The boy parades through the main street of the village with boyish antics and contortions meant to satirically imitate Pip. The gross, comic caricature openly exposes the hypocrisy of this new gentleman in a frock coat and top hat. Trabb's boy reveals that appearance has taken precedence over being, protocol on feelings, decorum on authenticity; labels reign to the point of absurdity, and human solidarity is no longer the order of the day.[151]

Estella and Miss Havisham represent rich people who enjoy a materially easier life but cannot cope with a tougher reality. Miss Havisham, like a melodramatic heroine, withdrew from life at the first sign of hardship. Estella, excessively spoiled and pampered, sorely lacks judgement and falls prey to the first gentleman who approaches her, though he is the worst. Estella's marriage to such a brute demonstrates the failure of her education. Estella is used to dominating but becomes a victim to her own vice, brought to her level by a man born, in her image.[152]

Dickens uses imagery to reinforce his ideas and London, the paradise of the rich and of the ideal of the gentleman, has mounds of filth, it is crooked, decrepit, and greasy, a dark desert of bricks, soot, rain, and fog. The surviving vegetation is stunted, and confined to fenced-off paths, without air or light. Barnard's Inn, where Pip lodges, offers mediocre food and service while the rooms, despite the furnishing provided, as Suhamy states, "for the money", is most uncomfortable, a far cry from Joe's large kitchen, radiating hearth, and his well-stocked pantry.[142]

Likewise, such a world, dominated by the lure of money and social prejudice, also leads to the warping of people and morals, to family discord and war between man and woman.[N 6] In contrast to London's corruption stands Joe, despite his intellectual and social limitations, in whom the values of the heart prevail and who has natural wisdom.[151]

Pip's conscience

[edit]

Another important theme is Pip's sense of guilt, which he has felt from an early age. After the encounter with the convict Magwitch, Pip is afraid that someone will find out about his crime and arrest him. The theme of guilt comes into even greater effect when Pip discovers that his benefactor is a convict. Pip has an internal struggle with his conscience throughout Great Expectations, hence the long and painful process of redemption that he undergoes.

Pip's moral regeneration is a true pilgrimage punctuated by suffering. Like Christian in Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress, Pip makes his way up to light through a maze of horrors that afflict his body as well as his mind. This includes the burns he suffers from saving Miss Havisham from the fire; the illness that requires months of recovery; the threat of a violent death at Orlick's hands; debt, and worse, the obligation of having to repay them; hard work, which he recognises as the only worthy source of income, hence his return to Joe's forge. Even more important, is his accepting of Magwitch, a coarse outcast of society.[153]

Dickens makes use of symbolism, in chapter 53, to emphasise Pip's moral regeneration. As he prepares to go down the Thames to rescue the convict, a veil lifted from the river and Pip's spirit. Symbolically the fog which enveloped the marshes as Pip left for London has finally lifted, and he feels ready to become a man.[154]

As I looked along the clustered roofs, with Church towers and spires shooting into the unusually clear air, the sun rose up, and a veil seemed to be drawn from the river, and millions of sparkles burst out upon its waters. From me too, a veil seemed to be drawn, and I felt strong and well.[155]

Pip is redeemed by love, that, for Dickens as for generations of Christian moralists, is only acquired through sacrifice.[156] Pip's reluctance completely disappears and he embraces Magwitch.[157] After this, Pip's loyalty remains constant, during the imprisonment, trial, and death of the convict. He grows selfless and his "expectations" are confiscated by the Crown. Moments before Magwitch's death, Pip reveals that Estella, Magwitch's daughter, is alive, "a lady and very beautiful. And I love her".[158] Here the greatest sacrifice: the recognition that he owes everything, even Estella, to Magwitch; his new debt becomes his greatest freedom.[157]

Pip returns to the forge, his previous state and to meaningful work. The philosophy expressed here by Dickens, that of a person happy with their contribution to the welfare of society, is in line with Thomas Carlyle's theories and his condemnation, in Latter-Day Pamphlets (1850), of the system of social classes flourishing in idleness, much like that of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels.[N 7][159] Dickens's hero is neither an aristocrat nor a capitalist but a working-class boy.[160]

In Great Expectations, the true values are childhood, youth and heart. The heroes of the story are the young Pip, a true visionary, and still developing person, open, sensible, who is persecuted by soulless adults. Then the adolescent Pip and Herbert, imperfect but free, intact, playful, endowed with fantasy in a boring and frivolous world. Magwitch is also a positive figure, a man of heart, victim of false appearances and of social images, formidable and humble, bestial but pure, a vagabond of God, despised by men.[N 8] There is also Pip's affectionate friend Joe, the enemy of the lie. Finally, there are women like Biddy.

Imperialism

[edit]Edward W. Said, in his 1993 work Culture and Imperialism, interprets Great Expectations in terms of postcolonial theory about late-eighteenth- and nineteenth-century British imperialism. Pip's disillusionment when he learns his benefactor is an escaped convict from Australia, along with his acceptance of Magwitch as surrogate father, is described by Said as part of "the imperial process", that is the way colonialism exploits the weaker members of a society.[161] Thus the British trading post in Cairo legitimatises Pip's work as a clerk, but the money earned by Magwitch's honest labour is illegitimate, because Australia is a penal colony, and Magwitch is forbidden to return to Britain.[N 9] Said states that Dickens has Magwitch return to be redeemed by Pip's love, paving the way for Pip's own redemption, but despite this moral message, the book still reinforces standards that support the authority of the British Empire.[162] Said's interpretation suggests that Dickens's attitude backs Britain's exploitation of Middle East "through trade and travel", and that Great Expectations affirms the idea of keeping the Empire and its peoples in their place—at the exploitable margins of British society.

However, the novel's Gothic and Romance genre elements, challenge Said's assumption that Great Expectations is a realist novel like Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe.[116]

Novels influenced by Great Expectations

[edit]Dickens's novel has influenced a number of writers. Sue Roe's Estella: Her Expectations (1982), for example, explores the inner life of an Estella fascinated with a Havisham figure.[163] Miss Havisham is again important in Havisham: A Novel (2013), a book by Ronald Frame, that features an imagining of the life of Miss Catherine Havisham from childhood to adulthood.[164] The second chapter of Rosalind Ashe's Literary Houses (1982) paraphrases Miss Havisham's story, with details about the nature and structure of Satis House and coloured imaginings of the house within.[165] Miss Havisham is also central to Lost in a Good Book (2002), Jasper Fforde's alternative history fantasy novel, which features a parody of Miss Havisham.[166] It won the Independent Mystery Booksellers Association 2004 Dilys Award.[167]

Magwitch is the protagonist of Peter Carey's Jack Maggs (1997), which is a re-imagining of Magwitch's return to England, with the addition, among other things, of a fictionalised Dickens character and plot-line.[168] Carey's novel won the Commonwealth Writers Prize in 1998. Mister Pip (2006), a novel by New Zealand author Lloyd Jones, won the 2007 Commonwealth Writers' Prize. Mister Pip is set in a village on the Papua New Guinea island of Bougainville during a brutal civil war there in the 1990s, where the young protagonist's life is impacted in a major way by her reading of Great Expectations.[169]

In May 2015, Udon Entertainment's Manga Classics line published a manga adaptation of Great Expectations.[170]

Adaptations

[edit]Like many other Dickens novels, Great Expectations has been filmed for the cinema or television and adapted for the stage numerous times. The film adaptation in 1946 gained the greatest acclaim.[171] The story is often staged, and less often produced as a musical. The 1939 stage play and the 1946 film that followed from that stage production did not include the character Orlick and ends the story when the characters are still young adults.[172] That character has been excluded in many televised adaptations made since the 1946 movie by David Lean.[172] Following are highlights of the adaptations for film and television, and for the stage, since the early 20th century.

- Film and television

- 1917 – Great Expectations, a silent film, starring Jack Pickford, directed by Robert G. Vignola. This is a lost film.[173]

- 1922 – Silent film, and the first adaptation not in English, made in Denmark, starring Martin Herzberg, directed by A. W. Sandberg.[174]

- 1934 – Great Expectations film starring Phillips Holmes and Jane Wyatt, directed by Stuart Walker.

- 1946 – Great Expectations, the most celebrated film version,[171] starring John Mills as Pip, Bernard Miles as Joe, Alec Guinness as Herbert, Finlay Currie as Magwitch, Martita Hunt as Miss Havisham, Anthony Wager as Young Pip, Jean Simmons as Young Estella and Valerie Hobson as the adult Estella, directed by David Lean. It came fifth in a 1999 BFI poll of the top 100 British films.

- 1954 – the first television adaptation shown as two-part television version starring Roddy McDowall as Pip and Estelle Winwood as Miss Havisham. It aired as an episode of the show Robert Montgomery Presents.[175]

- 1959 – BBC television version aired in 13 parts, starring Dinsdale Landen as Pip, Helen Lindsay as Estella, Colin Jeavons as Herbert Pocket, Marjorie Hawtrey as Miss Havisham and Derek Benfield as Landlord.[172] It was rebroadcast in 1960, but has not been seen since, as Part 8 is missing.

- 1967 – Great Expectations – a BBC television serial starring Gary Bond as Pip and Francesca Annis. BBC issued the series on DVD in 2017.[176]

- 1974 – Great Expectations – a film starring Michael York as Pip and Simon Gipps-Kent as Young Pip, Sarah Miles and James Mason, directed by Joseph Hardy.

- 1981 – Great Expectations – a BBC serial starring Stratford Johns, Gerry Sundquist, Joan Hickson, Patsy Kensit and Sarah-Jane Varley. Produced by Barry Letts, and directed by Julian Amyes.

- 1983 – an animated version, starring Phillip Hinton, Liz Horne, Robin Stewart and Bill Kerr, adapted by Alexander Buzo.[177]

- 1987 – Great Expectations: The Untold Story

- 1989 – Great Expectations, a Disney Channel two-part film starring Anthony Hopkins as Magwitch, John Rhys-Davies as Joe Gargery, and Jean Simmons as Miss Havisham, directed by Kevin Connor.

- 1998 – Great Expectations, a film starring Ethan Hawke, Gwyneth Paltrow, Robert De Niro, and Anne Bancroft, directed by Alfonso Cuarón. This adaptation is set in contemporary New York City, and renames Pip to Finn and Miss Havisham to Nora Dinsmoor. The film's score was composed by Patrick Doyle.

- 1999 – Great Expectations, a film starring Ioan Gruffudd as Pip, Justine Waddell as Estella, and Charlotte Rampling as Miss Havisham (Masterpiece Theatre—TV)

- 2000 – Pip, an episode of the television show South Park, starring Matt Stone as Pip, Eliza Schneider as Estella, and Trey Parker as Miss Havisham.

- 2011 – Great Expectations, a three-part BBC serial. Starring Ray Winstone as Magwitch, Gillian Anderson as Miss Havisham and Douglas Booth as Pip.

- 2012 – Great Expectations, a film directed by Mike Newell, starring Ralph Fiennes as Magwitch, Helena Bonham Carter as Miss Havisham and Jeremy Irvine as Pip.

- 2012 – Magwitch, a film written and directed by Samuel Supple, starring Samuel Edward Cook as Magwitch, Candis Nergaard as Molly and David Verrey as Jaggers. The film is a prequel to Great Expectations made for the Dickens bicentenary. It was screened at the Toronto International Film Festival and the Morelia International Festival.

- 2016 – Fitoor is an Indian Hindi-language romantic drama film directed by Abhishek Kapoor, starring Aditya Roy Kapur, Katrina Kaif, Tabu and Ajay Devgn. The film is set and filmed in Kashmir.[178][179]

- 2023 – Great Expectations, a six-part BBC and FX co-production, scripted and executive produced by Steven Knight, and starring Olivia Colman as Miss Havisham, Fionn Whitehead as Pip, Johnny Harris as Magwitch, Bashy as Jaggers, Shalom Brune-Franklin as Estella.[180]

- Stage