Ben Pimlott

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Ben Pimlott | |

|---|---|

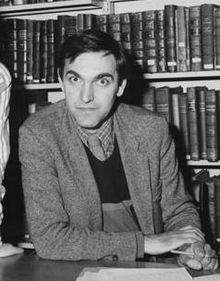

Pimlott in 1984 | |

| Born | Benjamin John Pimlott 4 July 1945 Merton, England |

| Died | 10 April 2004 (aged 58) London, England |

| Citizenship |

|

| Education | Rokeby School Marlborough College |

| Alma mater | Worcester College, Oxford Newcastle University |

| Occupation | Historian |

| Spouse | [1] |

| Children | 3[1] |

Benjamin John Pimlott FBA (4 July 1945 – 10 April 2004) was an historian of the post-war period in Britain. He made a substantial contribution to the literary genre of political biography.

Background

[edit]Ben Pimlott was born in Merton, Surrey, now Greater London, on 4 July 1945.[2] His father was John Pimlott, a civil servant at the Home Office and former private secretary to Herbert Morrison.[1] His mother, Ellen Dench Howes Pimlott, was American; her ancestors were Pilgrims, and she was a descendant of a victim of the Salem witch trials.[2] Pimlott held dual citizenship.[2] He grew up in Wimbledon and was educated at Rokeby School (which was then in Wimbledon), Marlborough College and Worcester College, Oxford, where he took a degree in Philosophy, Politics and Economics and a BPhil in politics, having originally won a scholarship to study there.[1][2] In 1970, despite a pronounced stammer, he was appointed as a lecturer in the politics department of the University of Newcastle, where he also took his PhD.[3]

In the February 1974 general election, Pimlott contested Arundel on behalf of the Labour Party, and Cleveland and Whitby the following October. Having lost on both occasions, he also contested the 1979 election, after which he left the North East to take up a research post at the London School of Economics, moving to a lectureship at Birkbeck College, London in 1981.[4]

Writing

[edit]During 1987–88, he was political editor of the New Statesman magazine and took on the post of Professor of Contemporary History at Birkbeck in 1988. For the following two years, Pimlott was responsible, with friends, for the short-lived journal Samizdat.[4]

Aside from his attempts at a Parliamentary career in the 1970s, not to mention his tenure as Chairman of the Fabian Society in 1993/1994, Pimlott is best remembered for his works of political biography including the lives of Hugh Dalton (1985), Harold Wilson (1992), and a study of Queen Elizabeth II (1996).[5] His study of Dalton won him the Whitbread Prize.[6]

His other books include Labour and the Left in the 1930s (1977),[6] The Trade Unions in British Politics (with Chris Cook, 1982), Fabian Essays in Socialist Thought (1984), The Alternative (with Tony Wright and Tony Flower, 1990), Frustrate their Knavish Tricks (1994) and Governing London (with Nirmala Rao, 2002).[2]

Views and legacy

[edit]Many of Pimlott's theses have stood the test of time,[citation needed] even if they were marginally controversial when originally published. His studies of the 1930s Labour left, the life of Harold Wilson and the constitutional effect of the monarchy in post-war Britain are said[by whom?] to have made his reputation as a biographer and even bestowed some additional credibility upon the subjects, all of which have received critical accounts under the pen of others. Pimlott was a critic of the concept of the post-war consensus in British politics, and believed that no such consensus actually existed.[2]

In 1996, his works were recognised with a fellowship of the British Academy. In 1998, he became Warden of Goldsmiths, University of London.[6]

Personal life, death and legacy

[edit]In 1977, Pimlott married Jean Seaton,[2] a lecturer on communications and the media at the University of Westminster. They had three children.[2]

Pimlott died from complications of an intracerebral hemorrhage and acute myeloid leukaemia at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery on 10 April 2004, at the age of 58.[2] In 2005, Goldsmiths named a major new Will Alsop-designed building on its New Cross site in his honour, and the Fabian Society and The Guardian inaugurated the first annual Ben Pimlott Prize for Political Writing.[7]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Ben Pimlott". The Telegraph. 13 April 2004. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Morgan, Kenneth O. (2009). "Pimlott, Benjamin John [Ben] (1945–2004), historian and political commentator". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/93657. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "Benjamin John Pimlott: 1945–2004" (PDF). Proceedings of the British Academy. 150. The British Academy: 161–179. 2007.

- ^ a b Morgan, Kenneth O. (12 April 2004). "Obituary: Ben Pimlott". The Guardian.

- ^ "Obituary: Ben Pimlott". Liverpool Daily Post. 14 April 2004. Retrieved 21 December 2021 – via The Free Library.

- ^ a b c "Ben Pimlott, 58, Historian and Biographer". The New York Times. The Associated Press. 17 April 2004. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ^ White, Michael (15 January 2005). "Pimlott prize unveiled". The Guardian.

Sources

[edit]- Julian Glover "Labour historian Pimlott dies at 58", The Guardian, 12 April 2004

- D. R. Thorpe Obituary: Professor Ben Pimlott, The Independent, 14 April 2004.

- 1945 births

- 2004 deaths

- 20th-century British biographers

- 20th-century British historians

- 21st-century British historians

- Academics of Birkbeck, University of London

- Academics of Goldsmiths, University of London

- Academics of Newcastle University

- Academics of the London School of Economics

- Alumni of Newcastle University

- Alumni of Worcester College, Oxford

- British people of American descent

- Chairs of the Fabian Society

- Deaths from intracranial haemorrhage

- Deaths from leukemia in England

- Fellows of the British Academy

- Labour Party (UK) parliamentary candidates

- Neurological disease deaths in England

- People associated with Goldsmiths, University of London

- People educated at Marlborough College

- Writers from Wimbledon, London