Bell Apartments

Bell Apartments | |

Bell Apartments in Seattle | |

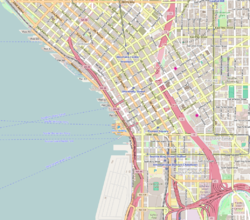

| Location | 2324 1st Ave. Seattle, Washington |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 47°36′51″N 122°20′44″W / 47.61417°N 122.34556°W |

| Built | 1889 |

| Architect | Elmer H. Fisher |

| Architectural style | Victorian, Gothic |

| NRHP reference No. | 74001957 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | 1974-07-12 |

| Designated SEATL | October 23, 1978[1] |

The Bell Apartments, also known as the Austin A. Bell Building is a historic building located at 2324 1st Avenue in the Belltown neighborhood of Seattle Washington. The building was named for Austin Americus Bell, son of one of Seattle's earliest pioneers, but built under the supervision of his wife Eva following Bell's unexpected suicide in 1889 soon after proposing the building.[2] It was designed with a mix of Richardsonian, Gothic and Italianate design elements by notable northwest architect, Elmer Fisher, who designed many of Seattle's commercial buildings following the Great Seattle fire.

The Bell Building, along with the adjacent Barnes and Hull Buildings, formed the nucleus of a development attempt in Belltown in the 1890s that never materialized. Originally designed for commercial use, the building's 65 office suites were being rented as unfurnished apartments by the end of 1890.[3] Early on, the building earned the moniker of Bell's Folly for being built so far away from the central business district in the then underdeveloped and economically depressed Belltown neighborhood, named for Bell's father, William Nathaniel Bell, once landowner of the entire north end of Seattle.[2] The area today is considered the heart of Belltown and the Bell building remains one of Belltown's most historic landmarks.

The building fell into disrepair throughout most of the 20th century, eventually losing its massive cornice to a fire in 1913. The building was first surveyed in June 1969 and included on the Municipal Art Commission List of Historic Buildings, at which time it was nominated for inclusion on the National Register. It was finally listed on the National Register of Historic Places on July 12, 1974.[4] It also became a Seattle City Landmark in 1978.[5] The upper floors stayed vacant until the 1990s, sustaining much weather damage in the meantime and later being destroyed by fire. Most of the building was rebuilt behind the main facade in 1997–1998 and now houses condominiums with a Starbucks Coffee on the first level.

Architecture

[edit]The Austin A. Bell Building is a four-story structure of brick with Terra cotta ornamentation. Both brick and Terra cotta are of a distinct reddish-orange hue and the mortar joints are narrow. Its architect, Elmer H. Fisher would later design many of the buildings in the Pioneer Square district of Seattle. While Fisher's designs were predominantly Richardsonian, the Bell Building is less so, with several Gothic elements thrown into the mix.

The ground floor served as a commercial space for two businesses and the windows are large for display purposes. Slender cast iron columns frame the recessed doorway. Wooden decorative panels appear above the transom of the double doors. A single door in an arched entry way at the south end of the storefront provides access to the upper floors. cast iron columns support the small arch and a decorative wooden panel also appears above the doorway.

Columns of pillowed granite blocks on either side of the doorway and storefront continue for the first story only and then are extended by brick pilasters to the full height of the building. The brick pilasters above the doorway continue above the fourth story to form a small tower. The tower is flat-roofed now but was originally capped by a shallow-pitched roof.

Window openings are deeply recessed. Windows occur in sets of three above the commercial section of the ground floor in pairs on either side of bordering pilasters. Single windows are placed on each floor above the south doorway. All windows on the second floor are tall and rectangular and the central group of three windows are separated by cast iron columns. The same pattern is repeated on the third and fourth floors although flanking openings on the third floor have segmental pointing arches and the narrow fourth-floor windows are fully arched. Terra cotta decorations appear above window openings on the second and third floors.

A high parapet extends above the fourth floor and it is composed of a more coarse brick than is the rest of the façade. This is the scar remaining from a large cornice made of pressed tin originally painted to match the stone, that was removed from the building after a 1913 fire, harming its architectural integrity greatly.[6] The pilasters continue through the parapet and the central pilasters and recessed within a brick equilateral arch is a false rose window design flanked at the base by Terra cotta fillets filling out the base of the arch.

The interior once featured a central courtyard that spanned the top three floors. It was lighted by a set of three large skylights. The interior finishing and moldings were typical for the time period and much of it was salvaged during the building's reconstruction in 1997.[7]

History

[edit]The Bell family and Belltown

[edit]Austin Americus Bell was the only son of William N. Bell, one of Seattle's founders and a member of the Denny Party that landed at Alki Point on November 13, 1851, on the schooner Exact. His land claim, adjacent to those of the Denny and Boren families, developed into the community of Belltown, which would later be absorbed by Seattle. Austin was born on January 9, 1854, in a log cabin across from the present site of the Bell Building, the second male white child born in the city. The cabin was destroyed in 1856 during The Battle of Seattle. Fed up with the instability of the area, the Bell family removed to California, where they remained for several years.[8]

Following the death of William Bell's wife in 1870, the family moved back to Seattle, now much more built up then when they had left. Austin however remained in San Francisco where he had built up a career in real estate. The value of Bell's property had skyrocketed in the previous years and he proceeded to make improvements to the land. In 1877, he constructed a two-story wooden building for the Odd Fellows on the site where his son's building would eventually stand.[9] In late 1883, the senior Bell completed his last great project, the four story wooden Bell Hotel at the corner of First and Battery Streets, adjacent to the Odd Fellows Hall.[i] Suffering from mental illness in his later years, William Bell died September 8, 1887, at the age of 70. He left to Austin a quarter his estate valued at $400,000, which continued to increase in value. Bell soon became one of Seattle's wealthiest citizens.[8]

Austin Bell's plans and final years

[edit]

During his father's illness and subsequent death, Austin began to see signs of similar mental illness in himself, now thought to be Alzheimer's disease. Austin was living and working in Seattle as a printer at the Puget Sound Dispatch when he was severely injured in a fireworks explosion on July 4, 1872. The explosion severely lacerated the lower part of his face, removing all the incisors from his lower jawbone. He had spent most of his life in San Francisco and many years traveling to seek medical treatment to restore his health, while retaining a real estate office in Seattle. Upon returning to Seattle at the beginning of 1889, he began making plans to erect a large brick building on the property he inherited just south of his father's hotel, since renamed the Bellevue House. The Odd Fellows, who were planning a large brick building of their own on the same site, made a deal with Bell to swap their property with the lot directly to the south, where their new lodge, now known as the Barnes Building would eventually rise. On April 23, 1889, Bell took his nephew, William M. Coffman, on a buggy ride to share his plans for the first time.[10] The next morning, his demeanor had changed and he claimed to be suffering from indigestion. He went to his realty office in Frye's Opera House as he usually did, locked the door behind him and shot himself in the head. A neighboring merchant heard the shot and rushed across the street to tell a pharmacist that a murder must have occurred. After summoning a doctor, several men broke down Bell's door to find him dead by his own hand. He was 35. A suicide note to Eva was discovered stating that he did not consider life with poor health worth living and expressed sorrow that he must take this way out.[8]

The Bell Building

[edit]Eva carried out her husband's plans, drawn by local architect Elmer Fisher, and dedicated the building in her husband's name. Completed in 1890, the building adorned in stone, pressed red brick shipped in from San Francisco and red Terra cotta cost $50,000 ($1.7 million in 2023 dollars) and was hailed as one of the showiest buildings in the city. The building contained two store rooms on the first floor and 65 apartments above, first known as the Bell Apartments[3] then later The Belle Apartments; the owners having parlayed Bell's name into the French word for "fine" or "pretty".[11] The first commercial tenants included the Woodhouse – Longuet & Co. Hardware store and Rafael Sartori's liquor store. Newspapers later noted the building as having the "dour, brooding aspect of the unhappy man that built it."[8]

During the Alaska Gold Rush of 1897, the Bell served as a hotel and dance hall. Pool tables were manufactured in the building in the early 1900s. In the early morning of May 12, 1913, a fire from a nearby building destroyed the roof and upper floor of the Bell Building, leading to the loss of most of the architectural elements above the roof line. At the time of the fire the top floor held a fully occupied boarding lodge known as The Sioux, but there were no deaths in the fire.[6] In 1937, for $9,800, the building was added to bargain real estate tycoon (and later Samis Foundation founder) Sam Israel's stock of low-maintenance properties. Like most of Israel's property, he kept the roof fixed, rented the retail space for cheap, and left the upper floors vacant.[12] While Belltown began to flourish as an artists' community in the 1970s, the Bell building continued to deteriorate.[13] Despite the shape it was in, it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1974 and became a City of Seattle Landmark on October 23, 1978.[5]

The Bell Building today

[edit]In 1982, the upper floors were ravaged by a fire, destroying much of what was left of the interior.[14] Developers Cassimar US Inc. and Murray Franklyn Co., working jointly as Austin A. Bell Associates L.L.C., bought the gutted and boarded up building and an adjoining parking area from the Samis Foundation in 1997 for $1 million.[7][15] Under the supervision of architect Chris Snell, all but the facade and the south wall of the building was demolished and a new 52-unit condominium structure with underground parking and 6,600 square feet (610 m2) of retail space was built in its shell while a new connecting building sympathetic in design to its neighbors was built on the parking lot.[16] The 6 million dollar project was completed by the Spring of 1998.[17][18] One of the first retail tenants was the fifth installment of Starbucks Coffee's short-lived concept restaurant, Cafe Starbucks. A regular Starbucks Coffee store currently occupies the entire first floor retail space.[19]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Bell's Hotel, later operating as the Bellevue House and finally the Bay View, was demolished in April 1937 and replaced by the two-story building still standing on the corner, originally the local distribution office for Paramount Pictures.

References

[edit]- ^ "Landmarks and Designation". City of Seattle. Archived from the original on March 6, 2013. Retrieved March 4, 2013.

- ^ a b Dorpat, Paul. Seattle Now & Then. 1st ed. Seattle, WA: Tartu Publications, 1984. 59. Print.

- ^ a b "The Bell Apartments". The Seattle Post-Intelligencer. December 21, 1890. p. 5. Retrieved December 30, 2020 – via Chronicling America.

- ^ Corley, Margaret. "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination form." Washington State Department of Archeology and Historic Preservation. National Park Service, 06-1969. Web. July 29, 2010. link Archived March 1, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "City of Seattle Legislative Information Service – Ordinance Number: 107753." City of Seattle: City Clerk's Online Information. City of Seattle, November 1, 1978. Web. July 29, 2010. link

- ^ a b "Famous Old Bell Block Scene of Nasty Blaze" Seattle Times May 12, 1913. Pg. 1.

- ^ a b Nabbefeld, Joe "Austin Bell building resurrected" Puget Sound Business Journal December 7, 1997. Retrieved November 6, 2010.

- ^ a b c d McDonald, Lucille, "Monument to an Unhappy Man" The Seattle Times May 14, 1967

- ^ "Belltown Improvements". The Daily Intelligencer. Library of Congress. March 15, 1877. Retrieved July 29, 2018.

- ^ "Weary of Life Austin A. Bell Commits Suicide". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. April 25, 1889.

- ^ [Insurance Map]. 1:50. Seattle, Washington 3rd ed. New York: Sanborn – Perris Map Co., 1893, sheet 59a.

- ^ Seven, Richard. "The Collector – Decades Sam Israel Bought Cheap and Never Sold. Today His Legacy Means Change for Seattle." Seattle Times April 11, 1999, final ed.: 16. Print.

- ^ Lentz, Florence K. "Belltown Buildings: High Hopes." Seattle Times July 30, 1989, weekend ed.: B4. Print.

- ^ Humphrey, Clark. Seattle's Belltown. San Francisco: Arcadia Publishing, 2007. 12. Print.

- ^ Rose, Cynthia. "Fighting for the Soul of Belltown – A Group of Artists, Small Businesses and Longtime Residents Want a Say in Changes to Their Downtown Neighborhood." Seattle Times March 11, 1997, final ed.: E1. Print.

- ^ "New Belle of Belltown :[FINAL Edition]. " Seattle Post – Intelligencer Aug. 26, 1998, Washington State Newsstand, ProQuest. Web. August 9, 2010.

- ^ Moriwaki, Lee. "Business." Seattle Times January 18, 1998, final ed.: F12. Print.

- ^ Virgin, Bill; P-I Reporter. "Anything but a Face Lift; Housing-Retail Plan Spares 1887 Facade :[FINAL Edition]. " Seattle Post – Intelligencer Mar. 1, 1997, Washington State Newsstand, ProQuest. Web. August 9, 2010.

- ^ "THE AUSTIN A. BELL BUILDING SIGNS UP TWO RESTAURANTS :[FINAL Edition]. " Seattle Post – Intelligencer Oct. 12, 1998, Washington State Newsstand, ProQuest. Web. August 9, 2010.

Further reading

[edit]- Kreisman, Lawrence (1985). Historic Preservation in Seattle. Seattle: Historic Seattle Preservation and Development Society.

- Ochsner, Jeffrey Karl (1994). Shaping Seattle Architecture: A Historical Guide to the Architects. Seattle: University of Washington Press. p. 339. ISBN 0-295-97366-8.

- Warren, James (1989). The Day Seattle Burned, June 6, 1889. Seattle: James R. Warren.

External links

[edit]- Image of Austin A. Bell ca. 1885 – Museum of History and Industry

- Image of Elmer Fisher's original design for the Bell Building – University of Washington special collections

- Image of Belltown c. 1898 showing the Bell Building in background – University of Washington special collections

- Image of Austin A. Bell Building on May 27, 1942 – Museum of History and Industry

- Commercial buildings completed in 1889

- 1880s architecture in the United States

- National Register of Historic Places in Seattle

- Residential buildings in Seattle

- Commercial buildings on the National Register of Historic Places in Washington (state)

- Apartment buildings in Washington (state)

- Residential buildings on the National Register of Historic Places in Washington (state)

- Buildings and structures in Belltown, Seattle

- 1889 establishments in Washington (state)