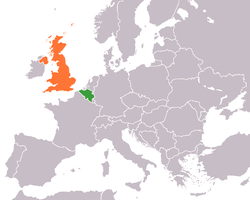

Belgium–United Kingdom relations

| |

Belgium |

United Kingdom |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Embassy of Belgium, London | Embassy of the United Kingdom, Brussels |

Belgium–United Kingdom relations are foreign relations between Belgium and the United Kingdom. Belgium has an embassy in London and 8 honorary consulates (in Belfast, Edinburgh, Gibraltar, Kingston-upon-Hull, Manchester, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Saint Helier, and Southampton).[1] The United Kingdom has an embassy in Brussels.[2]

Both countries are members of NATO, and both countries were member states of the European Union; however, the UK left the EU on 31 January 2020.[3] In addition, both countries' royal families are descended from the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, with the British branch being known as the House of Windsor and the Belgian branch as the House of Belgium.

History

[edit]

In the early years of the Hundred Years' War, Edward III of England allied with the nobles of the Low Countries and the burghers of Flanders against France. [citation needed]

Belgium established its independence in the revolution of 1830. Like the other European Great Powers, Britain was slow to recognise the new state. Even the election of Leopold of Saxe-Coburg, former son-in-law of Britain's King George IV and uncle to the future Queen Victoria, as King of the Belgians failed to win diplomatic recognition from London. Belgium's emergence had caused the break-up of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, one of several buffer states established after the end of the Napoleonic Wars as a check against future French expansion, and London feared this newly formed nation would be unable to survive hostile expansion by its neighbours. A British-organised European Congress produced the Treaty of London of 1839, whereby the Great Powers (and The Netherlands) all formally recognised the independence of Belgium, and (at Britain's insistence) guaranteed its neutrality.[4]

At the Berlin Conference (1884), Britain had recognised the Congo Free State as the personal domain of the King of the Belgians. Britain was subsequently to become a centre for opposition to Leopold II's personal rule in the territory through organisations such as the Congo Reform Association. At one point, Britain even demanded that the 14 signatories to the Berlin Conference meet again to discuss the situation. In 1908, Belgium's parliament took control of the Congo, which became a conventional European colony. In the years prior to World War I, many Belgians bore considerable resentment over Britain's campaign against Leopold II's activities in the Congo.[5]

The guarantees of neutrality of 1839 failed to prevent the invasion of Belgium by Germany in 1914. It was the final straw for an element of the Liberal Party that needed a moralistic reason to enter the war, beyond the need to prevent the defeat of France. Historian Zara Steiner says of German's invasion:

- The public mood did change. Belgium proved to be a catalyst which unleashed the many emotions, rationalizations, and glorifications of war which had long been part of the British climate of opinion. Having a moral cause, all the latent anti-German feelings, that by years of naval rivalry and assumed enmity, rose to the surface. The 'scrap of paper' proved decisive both in maintaining the unity of the government and then in providing a focal point for public feeling.[6] Much of the British fighting took place on Belgian soil, around Ypres. (Western Front (World War I)). During World War II, the Belgian government in exile based itself in London, as did the governments of many other countries; including France, Poland and Czechoslovakia.[7]

Around 250,000 Belgian refugees came to the UK during World War I; about 90% returned to Belgium soon after the war ended.[8] Agatha Christie's fictional detective Hercule Poirot was depicted as one of them.

Economic relations

[edit]

Historically, the south eastern parts of Great Britain and the area that is now Belgium has evidence of trade since the 1st century[9] and wool exports from the UK to cloth imports in the 10th-century County of Flanders. Flemish bricks were used on work to the Tower of London in 1278.[10] Today as much as 7.8% of Belgium’s exports are to the UK.[11] with just over 5% of Belgium's imports, over €12,000,000 coming from the UK.[12] Belgium is the UK's sixth-largest export market, worth £10,000,000 a year. The UK is Belgium's fourth-largest export market with two-way trade worth in the region of £22,000,000,000 of which £2,000,000,000 is in services.[13] The Golden Bridge Awards were established in 2012 for UK export success in Belgium and recognising the importance of a close by market.[14]

Following Brexit, Trade between the United Kingdom and Belgium is governed by the EU–UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement since 1 January 2021.[15][16]

Modern relations

[edit]Today, there are roughly 30,000 British people living in Belgium, and 30,000 Belgians living in the UK.[7] In 2014, the UK government announced £5,000,000 for the restoration of First World War graves in Flanders.[17]

Queen Elizabeth II made four state visits to Belgium during her reign; in 1966 (being received by King Baudouin), and in 1993, 1998 and 2007, where she was received by King Albert II.

Resident diplomatic missions

[edit]See also

[edit]- Anglo-Belgian Memorial (Brussels)

- Anglo-Belgian Memorial, London

- EU–UK relations

- List of Ambassadors from the United Kingdom to Belgium

References

[edit]- ^ "Honorary Consulates". Embassy of Belgium in the UK. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- ^ "UK and Belgium". Gov.uk. UK Government. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- ^ "Brexit: What you need to know about the UK leaving the EU". BBC News. 30 December 2020.

- ^ Paul Hayes, Modern British Foreign Policy: The Nineteenth Century 1814-80 (1975) pp. 174-93.

- ^ MacMillan, Margaret (2013). "Turning Out the Lights: Europe's Last Week of Peace". The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914. Random House. pp. 909–912 (e-book, page numbers approximate). ISBN 978-0-8129-9470-4.

- ^ Zara S. Steiner, Britain and the Origins of the First World War (1977) p 233.

- ^ a b "Belgium Country Profile, Foreign and Commonwealth Office". Archived from the original on 4 June 2011.

- ^ "World War One: How 250,000 Belgian refugees didn't leave a trace". BBC News. 15 September 2014.

- ^ British Iron Age

- ^ "Norfolk Historic Buildings Group Newsletter". nhbg.org.uk. Retrieved 24 August 2023.

- ^ "Belgium - the World Factbook". Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ^ "[Withdrawn] Exporting to Belgium - GOV.UK". Retrieved 24 August 2023.

- ^ "COBCOE - British Chamber of Commerce in Belgium". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- ^ "Golden Bridge Trade & Export Awards | British Chamber of Commerce in Belgium". Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- ^ "UK and EU agree Brexit trade deal". GOV.UK. 24 December 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- ^ "Brexit: Landmark UK-EU trade deal to be signed". BBC News. 29 December 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- ^ "Millions of pounds to support restoration and repair of First World War memorials".

Further reading

[edit]- Allen, Robert W. Churchill's Guests: Britain and the Belgian Exiles During World War II (Praeger, 2003).

- Allen Jr, Robert W. "Britain revives the Belgian army 1940–45." Journal of Strategic Studies 21.4 (1998): 78-96.

- Asquith, Herbert H. “Britain’s Tribute to Belgium.” Current History 4#6 (1916), pp. 1057–58, online.

- Bond, Brian. Britain, France, and Belgium, 1939-1940 (Brassey's, 1990). online review

- Declercq, Christophe. "The odd case of the welcome refugee in wartime Britain: uneasy numbers, disappearing acts and forgetfulness regarding Belgian refugees in the First World War." Close Encounters in War Journal 1.2 (2020): 5-26. online

- Demoor, Marysa. A Cross-Cultural History of Britain and Belgium, 1815–1918. Mudscapes and Artistic Entanglements (Palgrave/Macmillan, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-87926-6

- François, Pieter. "'A little Britain on the Continent': the British perception of Belgium (1830-70)" (Pisa University Press, 2010). link

- “German East Africa Divided Up: Belgium Gets Two Large Provinces, and Great Britain Takes the Rest, Renaming It Tanganyika Territory.” Current History 12#2 (1920), pp. 350–51 online.

- Green, Leanne. "Advertising war: Picturing Belgium in First World War publicity." Media, War & Conflict 7.3 (2014): 309-325. online

- Hayes, Paul. Modern British Foreign Policy: The Nineteenth Century 1814-80 (1975) pp. 174–93.

- Helmreich, Jonathan E. Belgium and Europe: A Study in Small Power Diplomacy (Mouton De Gruyter, 1976).

- Helmreich, Jonathan E. "Belgium, Britain, the United States and Uranium, 1952-1959." Studia Diplomatica (1990): 27-81 online.

- Ward, Adolphus William, and George Peabody Gooch. The Cambridge history of British foreign policy, 1783-1919. Vol. 1 (1929).

- Wilson, Trevor. "Lord Bryce's Investigation into Alleged German Atrocities in Belgium, 1914-15." Journal of Contemporary History 14.3 (1979): 369-383.