Beaune Altarpiece

The Beaune Altarpiece (or The Last Judgement) is a large polyptych c. 1443–1451 altarpiece by the Early Netherlandish artist Rogier van der Weyden, painted in oil on oak panels with parts later transferred to canvas. It consists of fifteen paintings on nine panels, of which six are painted on both sides. Unusually for the period, it retains some of its original frames.[1]

Six of the outer panels (or shutters) have hinges for folding; when closed the exterior view of saints and donors is visible. The inner panels contain scenes from the Last Judgement arranged across two registers. The large central panel spans both registers and shows Christ seated on a rainbow in judgement, while below him, the Archangel Michael holds scales to weigh souls. The lower register panels form a continuous landscape, with the panel on the far proper right showing the gates of Heaven, while the entrance to Hell is on the far proper left. Between these, the dead rise from their graves, and are depicted moving from the central panel to their final destinations after receiving judgement.

The altarpiece was commissioned in 1443 for the Hospices de Beaune in eastern France, by Nicolas Rolin, Chancellor of the Duchy of Burgundy, and his wife Guigone de Salins, who is buried in front of the altarpiece's original location.[2] It is in poor condition; it was moved in the 20th century both to shield it against sunlight and protect it from the almost 300,000 visitors the hospice receives annually.[2] It has suffered from extensive paint loss, the wearing and darkening of its colours, and an accumulation of dirt. In addition, a heavy layer of over-paint was applied during restoration. The two painted sides of the outer panels have been separated to be displayed; traditionally, the shutters would have been opened only on selected Sundays or church holidays.

Commission and hospice

[edit]Nicolas Rolin was appointed Chancellor of Burgundy by Philip the Good in 1422, a position he held for the next 33 years.[3] His tenure with the duke made him a wealthy man, and he donated a large portion of his fortune for the foundation of the Hôtel-Dieu in Beaune.[4] It is not known why he decided to build in Beaune rather than in his birthplace of Autun. He may have chosen Beaune because it lacked a hospital and an outbreak of the plague had decimated the population between 1438 and 1440.[5] Furthermore, in 1435, when the Treaty of Arras failed to bring a cessation to the longstanding hostility and animosity between Burgundy and France, Beaune suffered first the ravages of marauding bands of écorcheurs, who roamed the countryside scavenging in the late 1430s and early 1440s, then an ensuing famine.[6] The hospice was built after Rolin gained permission from Pope Eugene IV in 1441,[7] and was consecrated on 31 December 1452. At the same time, Rolin established the religious order of the sœurs hospitalières.[5] He dedicated the hospice to Anthony the Great, who was commonly associated with sickness and healing during the Middle Ages.[8]

Rolin declared in the hospice's founding charter, signed in August 1443, that "in the interest of my salvation ... in gratitude for the goods which the Lord, source of all wealth, has heaped upon me, from now on and for always, I found a hospital."[9][10] In the late 1450s, only a few years before he died, he added a provision to the hospital charter stipulating that the Mass for the Dead be offered twice daily.[11] Rolin's wife, Guigone de Salins,[A] played a primary role in the foundation, as probably did his nephew Jan Rolin. De Salins lived and served at the hospice until her own death in 1470.[3]

Documents relating to the altarpiece's commission survive, with the artist, patron, date of completion and place of installation all known – unusual for a Netherlandish altarpiece.[7] It was intended as the centrepiece for the chapel,[1] and Rolin approached Rogier van der Weyden around 1443, when the hospital was founded. The altarpiece was ready by 1451, the year the chapel was consecrated.[7] Painted in van der Weyden's Brussels workshop – most likely with the aid of apprentices – the panels were transported to the hospice once completed.[12] The altarpiece is first mentioned in a 1501 inventory, at which time it was positioned on the high altar.[1]

The polyptych was intended to provide both comfort and warning to the dying;[14] acting as a reminder of their faith and directing their last thoughts towards the divine. This is evident in its positioning within view of the patients' beds.[13] Medical care was expensive and primitive in the 15th century; the spiritual care of patients was as important as the treatment of physical ailments.[14] For those too ill to walk, Rolin specified that 30 beds be placed within sight of the altarpiece[15] which was visible through a pierced screen.[16] There were usually only two patients per bed, a luxury at a time when six to fifteen in a large bed was more common.[13]

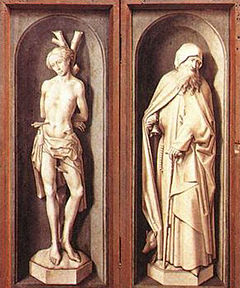

St Sebastian and St Anthony represent healing. Both were associated with bubonic plague and their inclusion is intended to reassure the dying that they will act as intercessors with the divine.[13] St Michael developed a cult following in 15th-century France, and he was seen as a guardian of the dead, a crucial role given the prevalence of plague in the region. There was another severe outbreak in 1441–1442, just before Rolin founded the hospital. According to the art historian Barbara Lane, patients were unlikely to survive their stay at Beaune, yet the representation of St Michael offered consolation as they could "gaze on his figure immediately above the altar of the chapel every time the altarpiece was opened. Like Saints Anthony and Sebastian on the exterior of the polyptych, the archangel offered ... hope that they would overcome their physical ills."[17]

Description

[edit]

The altarpiece measures 220 cm × 548 cm (87 in × 216 in),[18] and comprises fifteen separate paintings across nine panels, six of which are painted on both sides.[1] When the shutters are opened, the viewer is exposed to the expansive "Last Judgement" interior panels.[19] These document the possible spiritual fates of the viewers: that they might reach Heaven or Hell, salvation or damnation; stark alternatives appropriate for a hospice.[20] When the outer wings (or shutters) are folded, the exterior paintings (across two upper and four lower panels) are visible.[19] The exterior panels serve as a funerary monument for the donors. Art historian Lynn Jacobs believes that the "dual function of the work accounts for the choice of the theme of the Last Judgement on its interior".[20]

When the shutters are closed the polyptych resembles the upper portion of a cross.[21] The elevated central panel allowed additional space for a narrative scene depicting a heavenly vista, a single large figure, or a crucifixion with space for the cross to extend above the other panels. Van der Weyden conveys the heavenly sphere in the tall vertical panel, whereas the earthly is relegated to the lower-register panels and the exterior view. Moreover, the T-shape echoes typical configurations of Gothic churches, where the naves often extended past the aisles into the apse or choir.[22] The imagery of the outer panels is set in the earthly realm with the donors and the saints painted in grisaille to imitate sculpture.[22] Hence, the work clearly distinguishes between figures of the divine, earthly and hellish realms.[23]

Inner panels

[edit]As with van der Weyden's Braque Triptych, the background landscape and arrangements of figures extend across individual panels of the lower register[23] to the extent that the separations between panels are ignored.[24] There are instances of figures painted across two adjoining panels,[25] whereas Christ and St Michael are enclosed within the single central panel, giving emphasis to the iconography.[26] The celestial sphere, towards which the saved move, is dramatically presented with a "radiant gold background, spanning almost the entire width of the altarpiece".[27]

The lower register presents Earth and contains the gates to Heaven and Hell. The imposing figure of Christ indicates the "reign of heaven is about to begin."[28] The distinction between the earthly and heavenly realms creates a sense of order, and Christ "exudes calm and control", and a sense of balance and movement throughout the panels.[29]

The presentation of the resurrected dead across the five lower panels is reminiscent of a Gothic tympanum, specifically that at Autun Cathedral. Rolin would have been familiar with the Autun Cathedral entrances, which may have influenced his commissioning of a Last Judgement for the hospice.[29] Additionally, Rolin was aware of the liturgy associated with the Mass for the Dead, and would have known Last Judgement scenes associated with the Mass from 15th-century illuminated manuscripts, such as the full-page Last Judgement in the Hours of Catherine of Cleves, which shows Christ in a similar position, seated above the dead as they rise from their graves.[30]

Upper register

[edit]

Christ sits in judgement in the upper centre panel. He holds a lily in his right hand and a sword in his left, and sits on a rainbow extending across two panels, his feet resting on a sphere. His right hand is raised in the act of benediction, and his left hand is lowered. These positions indicate the act of judgement; he is deciding if souls are to be sent to Heaven or Hell,[31] his gestures echoing the direction and positioning of the scales held by the Archangel Michael beneath him. His palms are open, revealing the wounds sustained when they were nailed to the cross, while his cope gapes in places making visible the injury caused by the lance, from which pours deep-red blood.[32]

Christ's face is identical to the representation in the Braque Triptych, completed just a few years later in 1452.[33] Christ, placed so high in the pictorial space and spanning both registers, orchestrates the entirety of the inner panels. Whereas earlier Last Judgements might have seemed chaotic, here he brings a sense of order.[29]

The Archangel Michael, as the embodiment and conduit of divine justice, is positioned directly below Christ, the only figure to reach both Heaven and Earth. He wears a dispassionate expression as he holds a set of scales to weigh souls. Unusually for Christian art, the damned outweigh the blessed; Michael's scales have only one soul in each pan, yet the left pan tips below the right. Michael is given unusual prominence in a "Last Judgement" for the period, and his powerful presence emphasises the work's function in a hospice and its preoccupation with the liturgy of death. His feet are positioned as if he is stepping forward, about to move out of the canvas, and he looks directly at the observer, giving the illusion of judging not only the souls in the painting but also the viewer.[27]

-

Angels holding symbols of the Passion

-

Deësis to Christ's left

-

Two angels carrying the pillar on which Christ was scourged

Michael, like Sebastian and Anthony, was a plague saint and his image would have been visible to patients through the openings of the pierced screen as they lay in their beds.[34] He is portrayed with iconographic elements associated with the Last Judgement,[20] and, dressed in a red cope with woven golden fabrics over a shining white alb, is by far the most colourful figure in the lower panels, "hypnotically attracting the viewer's glance" according to Lane. He is surrounded by four cherubs playing trumpets to call the dead to their final destination.[35] Michael's role in the Last Judgement is emphasised through van der Weyden's use of colour: Michael's gleaming white alb contrasts with the cherubs' red vestments, set against a blue sky directly below heaven's golden clouds.[36]

Both of the upper register wings contain a pair of angels holding instruments of the Passion.[2] These include a lance, a crown of thorns and a stick with a sponge soaked in vinegar. The angels are dressed in white liturgical vestments, including an alb and an amice.[32]

Beneath Michael, souls scurry left and right. The saved walk towards the gates of Heaven where they are greeted by a saint; the damned arrive at the mouth of Hell and fall en masse into damnation.[29] The souls balanced in the scales are naked. The blessed look towards Christ, the banished look downwards. Reinforcing this is the word above the figure in the lighter pan, on the viewer's left, VIRTUTES (Virtues) and PECCATA (sins) above the lower figure in the heavier pan.[37] The scales are tilted in the same direction as Christ's sword. [B]

Lower register

[edit]The Virgin Mary, John the Baptist, the twelve Apostles and an assortment of dignitaries are positioned in a Deësis, at either side of Michael. The apostles are seated in a semicircle; St Peter is dressed in red on the far left, and St Paul, dressed in green, is on the far right. The seven haloed dignitaries, dressed in contemporary clothing, are unidentified but include a king, a pope, a bishop, a monk, and three women. Rather than general representative types, they are portraits of specific unidentified individuals, according to Shirley Blum.[38]

The dead rise from their graves around Michael's feet; some emerge to walk towards Heaven, others towards Hell. They are on a dramatically reduced scale compared to the saints. Lorne Campbell notes that the panels indicate a deeply pessimistic view of humanity, with the damned far outnumbering the saved,[37] especially compared to Stefan Lochner's Cologne panel, where the saved crowd around the gate to Heaven.[35]

The souls undergo a gradual transformation as they move from panel to panel. Those rising from their graves at Michael's feet show little expression, but become more animated as they move to either side; horror and desperation become especially visible on the faces of the damned as they move towards Hell.[39]

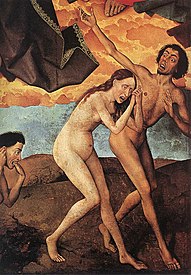

On the left, the saved have, according to Jacobs, "the same beatific expressions", but their postures gradually change from facing Christ and Michael to looking towards Heaven's gate, most notably with the couple below Mary where the man turns the woman's gaze away from Michael, and towards Heaven.[39] This contrasts with another couple on the opposite panel who face Hell; the woman is hunched over as the man raises his hand in vain to beseech God for mercy.[40]

Heaven is represented by an entrance to the Heavenly City, which is in a contemporary Gothic style illuminated by long, thin rays of light. The saved approach clasping their hands in prayer and are greeted at the entrance by an angel.[37] Only a few souls pass through the heavenly gates at a time.[35] The imagery of a church as an earthly representation of Heaven was popularised in the 13th century by theologians such as Durandus;[41] the gate to Heaven in this work resembles the entrance to the Beaune hospice.[42] The way to Heaven is shown clearly as a gilded church – the saved ascend a set of steps, turn right, and disappear from sight.[43] It is fully enclosed in a single panel, whereas Hell extends onto the adjoining panel, perhaps hinting that sin contaminates all around it.[44]

Van der Weyden depicts Hell as a gloomy, crowded place of both close and distant fires, and steep rock faces. The damned tumble helplessly into it, screaming and crying. The sinners enter Hell with heads mostly bowed, dragging each other along as they go.[36] Traditionally, a Last Judgement painting would depict the damned tormented by malevolent spirits; yet here the souls are left alone, the only evidence of their torment in their expressions.[37]

The hellscape is painted so as to instil terror, but without devils.[45] Erwin Panofsky was the first to mention this absence, and proposed that van der Weyden had opted to convey torment in an inward manner, rather than through elaborate descriptions of devils and fiends. He wrote, "The fate of each human being ... inevitably follows from his own past, and the absence of any outside instigator of evil makes us realize that the chief torture of the Damned is not so much physical pain as a perpetual and intolerably sharpened consciousness of their state".[46] According to Bernhard Ridderbos, van der Weyden accentuated the theme by "restricting the number of the dead and treating them almost as individuals. As the damned approach the abyss of hell they become more and more compressed."[36]

Exterior panels

[edit]

The six exterior panels consists of two donor wings, two containing saints, and two panels with Gabriel presenting himself to Mary. The donors are on the outer wings, kneeling in front of their prayer books. Four imitation statues in grisaille make up the inner panels. The lower two depict St Sebastian and St Anthony.[47] Sebastian was the saint of plagues and an intercessory against epidemics, Anthony the patron saint of skin diseases and ergotism, then known as St Anthony's Fire.[48] The two saints had close associations with the Burgundian court: Philip the Good was born on St Anthony's day, he had an illegitimate son named Anthony, and two of Rolin's sons were named Anthony. St Sebastian was the patron saint of Philip the Good's chivalric Order of the Golden Fleece.[49]

The two small upper register panels show a conventional Annunciation scene, with the usual dove representing the Holy Spirit.[1] The two sets of panels, unlike those on the interior, are compositionally very different. The figures occupy distinctly separate niches and the colour schemes of the grisaille saints and the donors contrast sharply.[20]

Like many mid-15th century polyptychs, the exterior panels borrow heavily from the Ghent Altarpiece, completed in 1432. The use of grisaille is borrowed from that work, as is the treatment of the Annunciation.[47] Van der Weyden uses iconography in the Beaune exterior that is not found in his other works, suggesting that Rolin may have asked that the altarpiece follow van Eyck's example.[19] Van der Weyden was not inclined merely to imitate though, and arranged the panels and figures in a concentrated and compact format.[47] Jacobs writes that "the exterior presents the most consistent pictorial rendering of trompe l'oeil sculpture to date". Gabriel's scroll and Mary's lily appear to be made of stone; the figures cast shadows against the back of their niches, creating a sense of depth which adds to the illusion.[20]

The exterior panels are drab, according to Blum, who writes that on Rolin's panel the most colourful figure is the red angel, which, with its gold helmet and keys, "emerges like an apparition".[19] Rolin and de Salins can be identified by the coats-of-arms held by the angels;[1] husband and wife kneel at cloth-covered prie-dieux (portable altars) displaying their emblems. Although De Salins was reputedly pious and charitable, and even perhaps the impetus for the building of the hospice, she is placed on the exterior right,[19] traditionally thought of as an inferior position corresponding to Hell, linking her to Eve, original sin and the Fall of man.[44]

Van Eyck had earlier portrayed Rolin in the c. 1435 Madonna of Chancellor Rolin, and the patron is recognizable from that work; both portraits show similar lips, a large chin and somewhat pointed ears. In van Eyck's portrait, Rolin is presented as perhaps pompous and arrogant; here – ten years later – he appears more thoughtful and concerned with humility.[50][51] Campbell notes wryly that van der Weyden may have been able to disguise the sitter's ugliness and age, and that the unusual shape of his mouth may have been downplayed. He writes that while "van Eyck impassively recorded, van der Weyden imposed a stylised and highly personal vision of the subject". Van Eyck's depiction was most likely the more accurate; van der Weyden embellished, mainly by lengthening the nose, enlarging the eyes and raising the eyebrows.[50]

Inscriptions

[edit]The panels contain quotations in Latin from several biblical texts. They appear either as lettering seemingly sewn into the edges of the figures' clothes (mostly hidden in the folds), or directly on the surface of the central inner panel.[52] The latter occur in four instances; two pairs of text float on either side of Christ, two around Michael. Beneath the lily, in white paint[36] are the words of Christ: VENITE BENEDICTI PATRIS MEI POSSIDETE PARATUM VOBIS REGNUM A CONSTITUTIONE MUNDI ("Come ye blessed of my father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundations of the world"). The text beneath the sword reads: DISCEDITE A ME MALEDICTI IN IGNEM ÆTERNUM QUI PARATUS EST DIABOLO ET ANGELIS EJUS ("Depart from me ye cursed, into everlasting fire, prepared for the devil and his angels").[C]

The inscriptions follow the 14th-century convention of showing figures, imagery and motifs associated with the saved to Christ's right, and those of the damned to his left. The words beneath the lily (the benedicti) read upwards towards Heaven, their curves leaning in towards Christ. The text to the left (the maledicti) flows in the opposite direction; from the highest point downwards. The inscriptions to Christ's right are decorated in light colours, to the extent that they are usually difficult to discern in reproduction. The lettering opposite faces downwards, and is applied with black paint.[53]

Condition

[edit]A number of the panels are in poor condition, owing variously to darkening of the colours, accumulated dirt and poor decisions during early restorations.[54] The altarpiece stayed in the chapel from the time of its installation until the French Revolution, from which it was hidden in an attic for decades. When it was brought out, the nude souls – thought to be offensive – were painted over with clothing and flames; it was moved to a different room, hung three metres (10 ft) from the ground, and portions were whitewashed. In 1836, the Commission of Antiquities retrieved it and began plans to have it restored.[55] Four decades later it underwent major restoration – between 1875 and 1878 – when many of these additions were removed, but not without significant damage to the original paintwork,[54] such as the loss of pigment to the wall-hangings in the donor panels, which were originally red and gold.[56] In general, the central inside panels are better preserved than the interior and exterior wings.[54] De Salins' panel is damaged; its colours have darkened with age; originally the niche was a light blue (today it is light green) and the shield held by the angel was painted in blue.[54]

The panels were laterally divided so both sides could be displayed simultaneously,[1] and a number have been transferred to canvas.[55]

Sources and influences

[edit]

Since before 1000, complex depictions of the Last Judgement had been developing as a subject in art, and from the 11th century became common as wall-painting in churches, typically placed over the main door in the west wall, where it would be seen by worshippers as they left the building.[57] Iconographical elements were gradually built up, with St Michael weighing the souls first seen in 12th-century Italy. Since this scene has no biblical basis, it is often thought to draw from pre-Christian parallels such as depictions of Anubis performing a similar role in Ancient Egyptian art.[58] In medieval English, a wall-painting of the Last Judgement was called a doom.[59]

Van der Weyden may have drawn influence from Stefan Lochner's c. 1435 Last Judgement, and a similar c. 1420 painting now in the Hotel de Ville, Diest, Belgium. Points of reference include Christ raised over a Great Deësis of saints, apostles and clergy above depictions of the entrance to Heaven, and the gates of Hell. In both of the earlier works, Christ perches on a rainbow; in the Deësis panel he is also above a globe. While the two earlier works are filled with dread and chaos, van der Weyden's panels display the sorrowful, self-controlled dignity typical of his best work. This is most evident in the manner in which the oversized and dispassionate Christ orchestrates the scene from Heaven.[60]

The work's moralising tone is apparent from some of its more overtly dark iconography, its choice of saints, and how the scales tilt far lower beneath the weight of the damned than the saved. The damned to Christ's left are more numerous and less detailed than the saved to his right. In these ways it can be compared to Matthias Grünewald's Isenheim Altarpiece, which served much the same purpose, having been commissioned for the Monastery of St Anthony in Isenheim, which cared for the dying.[13]

The similarities between the altarpiece and the c. late-1460s Last Judgement by van der Weyden's apprentice Hans Memling has led art historians to suggest a common tie with Florentine banker Angelo Tani who gave commissions to van der Weyden before his death in 1464. Because Memling's apprenticeship post-dated the completion and installation of the altarpiece, art historians speculate that Tani or Memling would have seen it in situ, or that Memling came into possession of a workshop copy.[61]

In Memling's work the Deësis and Christ's placement, above St Michael with his scales, are almost identical to the Beaune Altarpiece.[35] Despite the marked similarities, the crowded scenes in Memling's Last Judgement contrast sharply with "the hushed serenity of Rogier's composition", according to Lane,[35] and in a mirror image of van der Weyden's altarpiece, Memling shows the saved outweighing the damned in St Michael's scales.[61]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Scholars are unsure whether she was Rolin's second or third wife. See Lane (1989), 169

- ^ Technical analysis shows that the scales were at first tilted in the opposite direction.

- ^ Both inscriptions quote from Christ's discourse on The Sheep and the Goats (Matthew 25), see Ridderbos et al. (2005), 35

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Campbell (2004), 74

- ^ a b c Campbell (2004), 78

- ^ a b Smith (1981), 276

- ^ Vaughan (2012), 169

- ^ a b Blum (1969), 37

- ^ Vaughan (2012), 94

- ^ a b c Lane (1989), 167

- ^ Hayum (1977), 508

- ^ Smith (2004), 91

- ^ Lane (1989), 168

- ^ Lane (1989), 169

- ^ Jacobs (1991), 60; Lane (1989), 167

- ^ a b c d e Lane (1989), 170

- ^ a b Lane (1989), 171–72

- ^ Hayum (1977), 505

- ^ Lane (1989), 177–8

- ^ Lane (1989), 180

- ^ Campbell(1980), 64

- ^ a b c d e Blum (1969), 39

- ^ a b c d e Jacobs (2011), 112

- ^ Jacobs (1991), 33–35

- ^ a b Jacobs (1991), 36–37

- ^ a b Jacobs (1991), 60–61

- ^ Jacobs (2011), 97

- ^ Jacobs (2011), 98

- ^ Blum (1969), 43

- ^ a b Lane (1989), 177

- ^ Jacobs (2011), 60

- ^ a b c d Lane (1989), 172

- ^ Lane (1989), 176–77

- ^ Upton (1989), 39

- ^ a b McNamee (1998), 181

- ^ Blum (1969), 30

- ^ Lane (1989), 178

- ^ a b c d e Lane (1991), 627

- ^ a b c d Ridderbos et al. (2005), 35

- ^ a b c d Campbell (2004), 81

- ^ Blum (1969), 42

- ^ a b Jacobs (1991), 98–9

- ^ Jacobs (2011), 114

- ^ Jacobs (1991), 47

- ^ Blum (1969), 46

- ^ Jacobs (2011), 115

- ^ a b Jacobs (1991), 100

- ^ Drees (2000), 501

- ^ Panofsky (1953), 270

- ^ a b c Campbell (2004), 21

- ^ Lane (1989), 170–71

- ^ Blum (1969), 40–41

- ^ a b Campbell (2004), 22

- ^ Smith (1981), 273

- ^ Acres (2000), 86–7

- ^ Acres (2000), 87

- ^ a b c d Campbell (2004), 77

- ^ a b Ridderbos et al., (2005), 31

- ^ Campell (1972), 291

- ^ Hall (1983), 138–143

- ^ Hall (1983), 6–9

- ^ OED "Doom", 6

- ^ Lane (1989), 171

- ^ a b Lane (1991), 629

Sources

[edit]- Acres, Alfred. "Rogier van der Weyden's Painted Texts". Artibus et Historiae, Volume 21, No. 41, 2000.

- Blum, Shirley Neilsen. Early Netherlandish Triptychs: A Study in Patronage. Berkeley: California Studies in the History of Art, 1969. ISBN 0-520-01444-8

- Campbell, Lorne. Van der Weyden. London: Chaucer Press, 2004. ISBN 1-904449-24-7

- Campbell, Lorne. Van der Weyden. New York: Harper & Row, 1980. ISBN 0-06-430-650-X

- Campbell, Lorne. "Early Netherlandish Triptychs: A Study in Patronage by Shirley Neilsen Blum" (review). Speculum, Volume 47, No. 2, 1972.

- Drees, Clayton. The Late Medieval Age of Crisis and Renewal, 1300–1500. Westport: Greenwood, 2000. ISBN 0-313-30588-9

- Hall, James. A History of Ideas and Images in Italian Art. London: John Murray, 1983. ISBN 0-7195-3971-4

- Hayum, Andrée. "The Meaning and Function of the Isenheim Altarpiece: The Hospital Context Revisited". Art Bulletin, Volume 59, No. 4, 1977.

- Jacobs, Lynn. Opening Doors: The Early Netherlandish Triptych Reinterpreted. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2011. ISBN 0-271-04840-9

- Jacobs, Lynn. "The Inverted 'T'-Shape in Early Netherlandish Altarpieces: Studies in the Relation between Painting and Sculpture". Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, Volume 54, No. 1, 1991.

- Lane, Barbara. "Requiem aeternam dona eis: The Beaune Last Judgment and the Mass of the Dead". Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art, Volume 19, No. 3, 1989.

- Lane, Barbara. "The Patron and the Pirate: The Mystery of Memling's Gdańsk Last Judgment". The Art Bulletin, Volume 73, No. 4, 1991.

- McNamee, Maurice. Vested Angels: Eucharistic Allusions in Early Netherlandish paintings. Leuven: Peeters Publishers, 1998. ISBN 90-429-0007-5

- Panofsky, Erwin. Early Netherlandish Painting: Its Origins and Character. New York: Harper & Row, 1953.

- Ridderbos, Bernhard; Van Buren, Anne; Van Veen, Henk. Early Netherlandish Paintings: Rediscovery, Reception and Research. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-89236-816-0

- Smith, Jeffrey Chipps. The Northern Renaissance. London: Phaidon Press, 2004. ISBN 0-7148-3867-5

- Smith, Molly Teasdale. "On the Donor of Jan van Eyck's Rolin Madonna". Gesta, Volume 20, No. 1, 1981.

- Upton, Joel Morgan. Petrus Christus: his place in Fifteenth-Century Flemish painting. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1989. ISBN 0-271-00672-2

- Vaughan, Richard. Philip the Good. Martlesham: Boydell and Brewer, 2012. ISBN 978-0-85115-917-1

External links

[edit] Media related to Beaune Altarpiece at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Beaune Altarpiece at Wikimedia Commons

- 1445 paintings

- 1446 paintings

- 1447 paintings

- 1448 paintings

- 1449 paintings

- 1450 paintings

- Paintings based on the Book of Revelation

- Angels in art

- Polyptychs

- Paintings by Rogier van der Weyden

- Judgment in Christianity

- Paintings of Jesus

- Paintings of the Virgin Mary

- Paintings of John the Baptist

- Paintings of Michael (archangel)

- Paintings of apostles

- The Last Judgement in art

- Oil on panel paintings