Beauharnois scandal

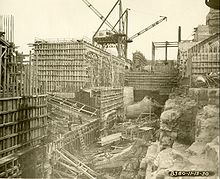

Construction in 1930 | |

| Date | 1929–1932 |

|---|---|

| Location | Quebec, Canada |

The Beauharnois scandal was a Canadian political scandal around 1930. The Beauharnois Light, Heat and Power Company had given $700,000 to the ruling Liberal Party of Canada in the run-up to the 1930 federal election in exchange for the right to change the flow of the St. Lawrence River through building a hydroelectric power station.[1]

The scandal "tainted" the reputation of Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, although it was not discovered until the year after he had lost the election.[2] Later commentators have suggested it was the "most famous" example of political bribery in the decade.[3][4]

The money

[edit]

The initial proposal to divert the river had met with opposition from rival hydroelectric companies, as well as shipping-related companies concerned about the impact on navigation and shipping.[5] Two Liberal senators, W. L. McDougald and Haydon, received contributions from the company president, R. O. Sweezey.[6][7] The donations were split between the Liberals' federal and Quebec provincial parties and were allegedly to secure the right to divert the St. Lawrence River 30 kilometres west of Montreal, to generate hydroelectricity.[8] It was later revealed that King had taken an all-expenses-paid holiday to Bermuda paid for by Beauharnois.[9] Having giving the Liberals the $700,000, Beauharnois made a similar offer to the Conservative party but it was believed that R. B. Bennett had forbidden the party to accept the pay-off.[10]

Aftermath

[edit]Discovered in 1931, two years after the event, the scandal occurred during one of the brief periods between the wars when King was not Prime Minister; he noted that it cast his party into "the valley of humiliation", and suggested he might resign from politics over the affair.[5][2] King ran again and was elected in the 1935 election and held onto the country's leadership for the next 13 years.[11] Haydon was dismissed from his position as campaign treasurer and McDougald was forced to resign from the Senate.[7] The scandal demonstrated the "emptiness and vacuity of the existing legislation" governing election campaign donations. No major changes occurred in the laws surrounding financing until three decades later,[12] although the National Liberal Federation was created in 1932 to provide distance between party leadership and campaign fundraising.[7] Maclean's magazine suggested that the scandal showed that both Canadian political parties had "become pensioners of selfish interests".[13]

Montreal Light, Heat & Power bought Beauharnois Light, Heat & Power in 1933 and continued the hydroelectric development initiated by Sweezey's; the first 16 units of the Beauharnois Hydroelectric Power Station were installed and commissioned between 1932 and 1941.[14] In Quebec, the scandal fuelled the cause of politicians — such as T.-D. Bouchard and Philippe Hamel — demanding the end of the so-called "electricity trust". Although the scandal did not topple the provincial government of Louis-Alexandre Taschereau, who was re-elected for a third term in the Quebec general election of 1931, the economic historian Albert Faucher wrote that it focused the public's attention on "the issue of electricity", which led a decade later to the nationalization of MLH & P and the establishment of Hydro-Québec.[15][16]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Regehr 1990

- ^ a b Rea, James Edgar (1997). T.A. Crerar: A Political Life. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-7735-1629-8.

- ^ Finkel, Alvin (1979). Business and social reform in the thirties. Toronto: J. Lorimer. p. 16.

- ^ Kipp, V. M. (1931-08-09). "Parliament's work finished in Canada". The New York Times. (subscription required)

- ^ a b McInnis, Edgar. "Canada - A Political and Social History", p. 459 ISBN 978-1-4067-5680-7

- ^ McNaught, Kenneth (1990-03-03). "Conflicts of interest are as Canadian as Mackenzie King". Toronto Star. Toronto.

- ^ a b c Beauharnois Scandal Archived 2007-05-14 at the Wayback Machine at The Canadian Encyclopedia

- ^ Kearney, Mark. "The Great Canadian Book of Lists", p. 241 ISBN 978-0-88882-213-0

- ^ Levine, Allan Gerald. "Scrum Wars: The Prime Ministers and the Media", p. 139 ISBN 978-1-55002-191-2

- ^ Waite, Peter B. "The Lives of Dalhousie University: 1925–1980, the old college transformed", p. 55 ISBN 978-0-7735-1166-8

- ^ Robert MacGregor Dawson; H. Blair Neatby (1958). William Lyon Mackenzie King: 1874-1923. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9780802053817.

- ^ Alexander, Herbert E. "Comparative Political Finance in the 1980s", p. 52 ISBN 978-0-521-36464-5

- ^ MacKay, R. A. (1932-10-15). "After Beauharnois - what?". Maclean's.

- ^ McNaughton 1970, p. 35

- ^ Saint-Germain 1960, p. 134

- ^ Faucher 1992, p. 430

Further reading

[edit]Books

[edit]- Dales, John H. (1957). Hydroelectricity and Industrial Development Quebec 1898-1940. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- McNaughton, Ian (1970). Beauharnois. Montreal: Hydro-Québec..

- Regehr, Theodore David (1990). The Beauharnois scandal : a story of Canadian entrepreneurship and politics. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-2629-X.

Papers

[edit]- Faucher, Albert (September 1992). "La question de l'électricité au Québec durant les années trente". L'actualité économique (in French). Vol. 68, no. 3. pp. 415–432.

- McNaughton, W.J.W. (February 1962). "Beauharnois : A dream come true". Canadian Geographical Journal. Vol. LXIV, no. 2. Ottawa. pp. 40–65.

- Saint-Germain, Clément (1960). "RUMILLY, Robert, La Dépression. Tome XXXII. Histoire de la Province de Québec (Fides, Montréal, 1960)". Revue d'histoire de l'Amérique française (in French). Vol. 14, no. 1. pp. 133–135.

- Vallières, Marc (1990). "REGEHR, T. D., The Beauharnois Scandal: A Story of Canadian Entrepreneurship and Politics. Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 1990. 234 p." Revue d'histoire de l'Amérique française (in French). Vol. 44, no. 1. pp. 117–119.