Beauford Delaney

Beauford Delaney | |

|---|---|

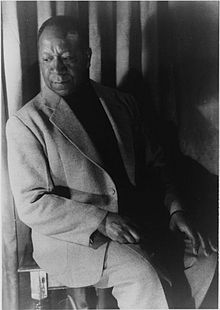

Beauford Delaney, photographed by Carl Van Vechten in 1953 | |

| Born | December 30, 1901 Knoxville, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Died | March 26, 1979 (aged 77) Paris, France |

| Resting place | Thiais Cemetery Paris, France |

| Known for | Painting |

| Movement | Harlem Renaissance |

Beauford Delaney (December 30, 1901 – March 26, 1979) was an American modernist painter. He is remembered for his work with the Harlem Renaissance in the 1930s and 1940s, as well as his later works in abstract expressionism following his move to Paris in the 1950s. Beauford's younger brother, Joseph, was also a noted painter.[1]

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]Beauford Delaney was born December 30, 1901, in Knoxville, Tennessee. Delaney's parents were prominent and respected members of Knoxville's black community. His father Samuel was both a barber and a Methodist minister. His mother Delia was also prominent in the church, and earned a living taking in laundry and cleaning the houses of prosperous white families. Delia, born into slavery and never able to read and write herself, transferred a sense of dignity and self-esteem to her children, and preached to them about the injustices of racism and the value of education. Beauford was the eighth of ten children, only four of whom survived into adulthood. He summed up the reasons for this in a journal entry from 1961, saying "so much sickness came from improper places to live – long distances to walk to schools improperly heated… too much work at home – natural conditions common to the poor that take the bright flowers like terrible cold in nature…"[2]

Beauford and his younger brother Joseph were both attracted to art from an early age. Some of their earliest drawings were copies of Sunday school cards and pictures from the family bible. "Those early years which Beauford and I enjoyed together I am sure shaped the direction of our lives as artists. We were constantly doing something with our hands – modelling with the very red Tennessee clay, also copying pictures. One distinct difference in Beauford and myself was his multi-talents. Beauford could always strum on a ukulele and sing like mad and could mimic with the best. Beauford and I were complete opposites: me an introvert and Beauford the extrovert."[3] The Delaneys attended Knoxville's Austin High School, and among Beauford's early works was a portrait of Austin High principal Charles Cansler.[4]

When he was a teenager, he got a job as a "helper" at the Post Sign Company. However, he and his younger brother Joseph were drawing signs of their own. Then some of his work was noticed by Lloyd Branson, an elderly American Impressionist and Knoxville's best known artist. By the early 1920s, Delaney became the apprentice of Branson.[5] With Branson's encouragement, the 23-year-old Delaney migrated north to Boston to study art. With perseverance, he achieved the artist's education he desired, including informal studies at the Massachusetts Normal School, the South Boston School of Art and the Copley Society. He learned what he called the "essentials" of classical technique. It was also while in Boston that Delaney had his first "intimate experience" with a young man in the Public Garden. Through letters of introduction from Knoxville, he also received what he referred to as a "crash course" in black activist politics and ideas by associating socially during his years in Boston with some of the most sophisticated and radical African Americans of the time, such as James Weldon Johnson, writer, diplomat and rights activist; William Monroe Trotter, founder of the National Equal Rights League; and Butler Wilson, board member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. By 1929, the essentials of his artistic education complete, Beauford decided to leave Boston and head for New York.

New York City, USA

[edit]His arrival in New York City at the time of the Harlem Renaissance was exciting. Harlem was then the center of black cultural life in the United States. But it was also the time of the Great Depression, and it was this that Beauford was confronted with on his arrival. "Went to New York in 1929 from Boston all alone with very little money…this was the depression, and I soon discovered that most of these people were people out of work and just doing what I was doing – sitting and figuring out what to do for food and a place to sleep."[6]

Delaney felt an immediate affinity with this "multitude of people of all races – spending every night of their lives in parks and cafes" surviving on next to nothing. Their courage and shared camaraderie inspired him to feel that "somehow, someway there was something I could manage if only with some stronger force of will I could find the courage to surmount the terror and fear of this immense city and accept everything insofar as possible with some calm and determination".

Members of this disenfranchised community became the subjects of many of Delaney's greatest New York period paintings. In New York "he painted colourful, engaging canvasses that captured scenes of the urban landscape…his works from that period express, in an American Modernist vein, not only the character of the city, but also his personal vision of equality, love, and respect among all people".[7] One of Delaney's works from this period, Can Fire in the Park (oil on canvas, 1946), where a group of men huddle together for warmth and companionship around an open fire, is described by the Smithsonian American Art Museum as a "disturbingly contemporary vignette [which] conveys a legacy of deprivation linked not only to the Depression years after 1929 but also to the longstanding disenfranchisement of black Americans, portrayed here as social outcasts… Despite its sober subject, the scene crackles with energy, the culmination of Delaney's sharp pure colors, thickly applied paints, and taut, schematic patterning. Abandoning the precise realism of his early academic training, Delaney developed a lyrically expressive style that drew upon his love of musical rhythms and his improvisational use of color." Works such as Can Fire in the Park "hover between representation and abstraction as that style evolved during the 1940s."

Delaney found "little corners in the world of the Great Depression that would or could be receptive to his work."[8] He earned a studio space and place to live through his work at the Whitney as a guard, telephone operator and gallery attendant.

Commendably, Delaney established himself as a well known part of the bohemianism of the art scene of the period. His friends included the "poet laureate" of the period, Countee Cullen, artist Georgia O'Keeffe, and writer Henry Miller, among many others. He became the "spiritual father" of the young writer James Baldwin.

Despite the friendships and successes of this period, he remained a rather isolated individual. David Leeming, in his 1998 biography Amazing Grace: a life of Beauford Delaney, presents Delaney as having led a very "compartmentalized" life in New York.

In Greenwich Village, where his studio was, Delaney became part of a gay bohemian circle of mainly white friends; but he was furtive and rarely comfortable with his sexuality.

When he traveled to Harlem to visit his African-American friends and colleagues, Delaney made efforts to ensure that they knew little of his other social life in Greenwich Village. He feared that many of his Harlem friends would be uncomfortable or repelled by his homosexuality.

He had "a third life" centered on questions concerning the aesthetics and development of modernism in Europe and the United States; primarily influenced by the ideas of his friends, photographer Alfred Stieglitz and the cubist artist Stuart Davis (painter), and the paintings of the European modernists and their predecessors like Cézanne, Matisse, Picasso, and Van Gogh.

The pressures of being "black and gay in a racist and homophobic society" would have been difficult enough, but Delaney's own Christian upbringing and "disapproval" of homosexuality, the presence of a family member (his artist brother Joseph) in the New York art scene and the "macho abstract expressionists emerging in lower Manhattan's art scene" added to this pressure. So he "remained rather isolated as an artist even as he worked in a center of major artistic ferment… A deeply introverted and private person, Delaney formed no lasting romantic relationships."[9]

While he worked to incorporate African-American influences, such as the "Negro" idiom of jazz, into his own artwork, he often preferred to visit one of the clubs when he was in Harlem rather than join in the serious socio-political discussions or "Negro art" questions that were taking place at the "306 Group" or the Harlem Artists Guild. Though he resisted thinking of himself as a Negro artist, Beauford had tremendous pride in black achievement. He was also pleased to participate in a number of black artists exhibitions with fellow artists like Jacob Lawrence, Romare Bearden, Hale Woodruff, Selma Burke, Richmond Barthé, Norman Lewis, and his brother Joseph Delaney.

The Smithsonian American Art Museum notes that "neither early success nor gracious spirit spared Delaney from the obscurity and poverty" that plagued most of his adult life. Brooks Atkinson wrote in his 1951 book Once Around the Sun: "No one knows exactly how Beauford lives. Pegging away at a style of painting that few people understand or appreciate, he has disciplined himself, not only physically but spiritually, to live with a kind of personal magnetism in a barren world."

Delaney's paintings seem to say, "I may be suffering, but what an experience this is." Delaney's work "is never depressing, though Beauford was often depressed; he could say yes to life in spite of the fact that life was kicking him in the butt."[10]

Paris

[edit]

In 1953, at the age of 52, and just as the center of the art world was shifting to New York, Delaney left New York for Paris. Europe had already attracted many other African-American artists and writers who had found a greater sense of freedom there. Writers Richard Wright, James Baldwin, Chester Himes, Ralph Ellison, William Gardner Smith and Richard Gibson, and artists Harold Cousins, Herbert Gentry and Ed Clark[11] had all preceded him in journeying to Europe. In his journal, Richard Wright described Paris as "a place where one could claim one's soul."

Europe became Delaney's home for the remainder of his life. About his new life and possibilities, Beauford entreated himself to "Keep the faith and trust in so far as possible. Love humility and don’t mind the insinuations that cause sorrow…and loneliness and limitations. We learn self-reliance and to hear the voice of God, too…and how to…not break but bend gently. Learning to love is learning to suffer deeply and with quietness."[12]

His years in Paris led to a dramatic stylistic shift from the "figurative compositions of New York life to abstract expressionist studies of color and light."[7]

"Delaney's relationship with abstraction predated the notorious Abstract Expressionist movement, positioning him as a forerunner of one of the most important ideological and stylistic developments in twentieth-century American art. Although he chose not to identify himself with the movement, as the Abstract Expressionists began to gain notoriety in the late 1940s, Delaney's abstract work increasingly gained attention."[13]

Though abstract expressionist work predominated during this period, Delaney still produced figurative compositions. His portrait of James Baldwin (1963, pastel on paper) is described by the US National Portrait Gallery as "heated and confrontational, its harsh colors roughly applied" and glowing with "the vibrant, Van Gogh-inspired yellow the artist often used after he moved to Paris." The portrait "is both a likeness based on memory and a study in light."

Delaney's drive to continuously paint resulted in him using his raincoat when he was out of canvas, "Untitled, 1954" is an oil on raincoat fragment.[14]

Mental deterioration

[edit]By 1961, heavy drinking had begun to impair Delaney's often fragile mental and physical health.[15] Periods of lucidity were interrupted by days and sometimes weeks of madness.[16] This pattern continued for the remainder of his life.

Continued poverty, hunger and alcohol abuse fueled his deterioration. James Baldwin said of Delaney:

He has been starving and working all of his life – in Tennessee, in Boston, in New York, and now in Paris. He has been menaced more than any other man I know by his social circumstances and also by all the emotional and psychological stratagems he has been forced to use to survive; and, more than any other man I know, he has transcended both the inner and outer darkness.[17]

He returned briefly to the United States in 1969 to see his family, dogged by mental illness. He believed malicious people came to him at night "and speak unpleasant and vulgar language and threaten malicious treatment…interfering with my health and urgent work…the constant, continuous creation."[18]

Shortly after his return to Paris in January 1970, Beauford began to display early symptoms of Alzheimer's disease. By the early 1970s, Beauford's sickness coupled with his financial instability made clear that he could no longer cope with daily life.[19] In the autumn of 1973 his friend, Charles Gordon (Charley) Boggs, wrote to James Baldwin, "Our blessed Beauford is rapidly losing mental control." His friends tried to care for him but, in 1975, he was hospitalized and then committed to St Anne's Hospital for the Insane. Beauford Delaney died in Paris while at St Anne's on March 26, 1979.[20] Charles Boggs handled Delaney's will, written on a scrap of paper, in which Delaney had requested that he be buried in Potter's Field.[21]

In his Introduction to the Exhibition of Beauford Delaney opening December 4, 1964 at the Gallery Lambert, James Baldwin wrote:

The darkness of Beauford's beginnings, in Tennessee, many years ago, was a black-blue midnight indeed, opaque and full of sorrow. And I do not know, nor will any of us ever really know, what kind of strength it was that enabled him to make so dogged and splendid a journey.

Legacy

[edit]Following Delaney's death, he was praised as a great and neglected painter but, with a few notable exceptions, the neglect continued.

A retrospective of his work at the Studio Museum in Harlem a year before his death did little to revive interest in his work. It was not until the 1988 exhibition Beauford Delaney: From Tennessee to Paris, curated by the French art dealer Philippe Briet at the Philippe Briet Gallery, that Delaney's work was again exhibited in New York, followed by two retrospectives in the gallery: Beauford Delaney: A Retrospective [50 Years of Light] in 1991, and Beauford Delaney: The New York Years [1929–1953] in 1994.

"Whatever Happened to Beauford Delaney?", an article by Eleanor Heartney, appeared in Art in America in response to the 1994 exhibition asking why this once well regarded "artist's artist" was now virtually unknown to the American art public. "What happened? Is this another case of an over-inflated reputation returning to its true level? Or was Delaney undone by changing fashions which rendered his work unpalatable to succeeding generations? Why did Beauford Delaney so completely disappear from American art history?" The author believed that Delaney's disappearance from the consciousness of the New York art world was linked to "his move to Paris at a crucial moment in the consolidation of New York's position as the world's cultural capital and his work's irrelevance to the history of American art as it was being written by critics" at the time. The article concludes, "Today [1994] as those histories unravel and are replaced by narratives with a more varied and colorful weave, artists like Delaney can be seen in a new light."[15]

In 1985, James Baldwin described the impact of Delaney on his life, saying he was "the first living proof, for me, that a black man could be an artist. In a warmer time, a less blasphemous place, he would have been recognised as my Master and I as his Pupil. He became, for me, an example of courage and integrity, humility and passion. An absolute integrity: I saw him shaken many times and I lived to see him broken but I never saw him bow."[22] Baldwin marveled over Delaney's ability to emulate such light in his work despite the darkness he was surrounded by for the majority of his life. It is this insight of Delaney’s past, Baldwin believes, that serves as evidence for the true victory Delaney secured. Baldwin admired his keen ability to “lead the inner and the outer eye, directly and inexorably, to a new confrontation with reality." He further wrote, "Perhaps I should not say, flatly, what I believe – that he is a great painter – among the very greatest; but I do know that great art can only be created out of love, and that no greater lover has ever held a brush."[23]

Delaney's work has now been exhibited by, among others, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Cleveland Museum of Art, Harvard University Art Museums, Art Institute of Chicago, Knoxville Museum of Art, The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, The Newark Museum, The Studio Museum in Harlem, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum. His work has also been exhibited by a number of galleries, including the Anita Shapolsky Gallery and the Michael Rosenfeld Gallery in New York City.[24][25]

The Showtime series Flatbush Misdemeanors pays tribute to Delaney with one of the protagonists teaching at Beauford Delaney High School, a fictional public school set in Flatbush, Brooklyn.[26]

The Beauford Delaney burial site

[edit]

In 2009, while researching an article on African-American gravesites in Paris, freelance writer Monique Y. Wells learned that Delaney was buried in an unmarked grave at the Cemetery of Thiais and that his remains would be moved to a common grave by the end of the year if the "concession" (the equivalent of a lease) on his grave was not renewed. Friends of Delaney raised the sum required, and Wells paid the fee to the cemetery to preserve Delaney's resting place.[27]

In November 2009, Wells founded a French non-profit association, Les Amis de Beauford Delaney, to support fundraising for a tombstone. Fundraising began in February 2010, and the association ordered the stone by June 2010. The installation was completed by August 2010.[28][29]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Beauford Delaney Archived May 10, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, University of Tennessee website. Retrieved: January 27, 2013.

- ^ Journal of Beauford Delaney, quoted in Leeming 1998:13.

- ^ Joseph Delaney, ""A Tale of Two Brothers" by Jack Neely". Archived from the original on July 7, 2013. Retrieved 2013-07-07. 1978.

- ^ Jack Neely, "The Life of Knoxville Artist Beauford Delaney (1901-1979) Archived June 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine," Knoxville Mercury, 18 February 2016.

- ^ Neely, Jack. Knoxville's Secret History. Scruffy City Publishing, 1995.

- ^ Journal of Beauford Delaney, quoted in Leeming 1998:32.

- ^ a b Canterbury 2004.

- ^ Leeming 1998:36.

- ^ Neuman 2005.

- ^ Biographer, David Leeming, quoted in Neely 1997.

- ^ Studio Museum in Harlem (1996) Explorations in the City of Light. New York: Studio Museum in Harlem. January 18 – June 2, 1996. Texts by Kinshasa Holman Conwill, Catherine Bernard, Peter Selz, Michel Fabre, Valerie J. Mercer.

- ^ Journal of Beauford Delaney, quoted in Leeming 1998:127.

- ^ Adrienne Childs, University of Maryland.

- ^ Delaney, Beauford (January 11, 2017). "Beauford Delaney". new.artsmia.org/. Archived from the original on February 6, 2017. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ a b Heartney 1994.

- ^ Leeming 1998.

- ^ James Baldwin, December 4, 1963.

- ^ Journal of Beauford Delaney.

- ^ Crouch, Kaye (Spring 2002). "Beauford Delaney (American, 1910-1979)". Tennessee Historical Quarterly. 61 (1): 37–38. JSTOR 42631069.

- ^ "Beauford Delaney | Smithsonian American Art Museum". americanart.si.edu. Retrieved January 21, 2021.

- ^ Monique Y. Wells, Burial Site of Knoxville's Beauford Delaney remains undisturbed thanks to friends admirers, KnoxNews.com, September 13, 2009.

- ^ James Baldwin, from The Price of the Ticket, 1985.

- ^ Baldwin, James (1997). "On the Painter Beauford Delaney". Transition (75/76): 88–89. doi:10.2307/2935393. ISSN 0041-1191. JSTOR 2935393.

- ^ "Delaney, Beauford". anitashapolskygallery.com. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ^ "Beauford Delaney 1901-1979, US". ArtFacts.net. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ^ Delaney, Beauford (January 11, 2017). "Flatbush Misdemeanors Beauford Delaney". tshirtonscreen.com/. Archived from the original on June 10, 2021. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- ^ Wells, Monique Y. (February 10, 2010). "Beauford's Eternal Home - Thiais Cemetery". Les Amis de Beauford Delaney. Retrieved December 11, 2021.

- ^ Wells, Monique Y. (September 2, 2010). "Beauford's Tombstone is in Place!". Les Amis de Beauford Delaney. Retrieved December 11, 2021.

- ^ Cigainero, Jake (September 8, 2016). "Beauford Delaney". New York Times. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

External links

[edit]Works:

- Can Fire in the Park, oil on canvas, Smithsonian, 1946

- Self Portrait, Yaddo, 1950

- Untitled, gouache on paper, 1960

- Selected Paintings, Beauford Delaney: from New York to Paris, Exhibition Website

- Abstraction, gouache on paper, 1958-1961

- Charlie Parker Yardbird, oil on canvas, 1958

- Untitled, oil on canvas, 1958

References

[edit]- Baldwin, James, 1964, "Introduction to the Exhibition of Beauford Delaney opening December 4, at the Gallery Lambert", reprinted in Beauford Delaney: A Retrospective, Studio Museum of Harlem, 1978.

- Canterbury, Patricia Sue, 2004, Beauford Delaney: from New York to Paris, University of Washington Press.

- Delaney, Joseph, 1978, Beauford Delaney, My Brother, from Beauford Delaney: A Retrospective, Studio Museum of Harlem, 1978.

- Heartney, Eleanor, 1994, Whatever happened to Beauford Delaney? – Philippe Briet Gallery, New York, Art in America.

- Leeming, David, 1998, Amazing Grace: a life of Beauford Delaney, Oxford University Press.

- Miller, Henry1945 The Amazing and Invariable Beauford Delaney, reprinted in Beauford Delaney: A Retrospective, Studio Museum of Harlem, 1978.

- Neely, Jack, 1995, "No Greater Lover", Metro Pulse, Volume 5, Number 8.

- Neely, Jack, 1997, "A Tale of Two Brothers", Metro Pulse, Volume 7, Number 13, April 3–10.

- Neumann, Caryn E., 2005, An Encyclopedia of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender & Queer Culture.

- Boudou, Karima, 2018, Double Vision: Beauford Delaney and Ted Joans in France, Africanah.

- Smithsonian American Art Museum Biography of Beauford Delaney.

- 1901 births

- 1979 deaths

- American expatriates in France

- 20th-century American painters

- American male painters

- Painters from New York City

- Painters from Tennessee

- African-American LGBTQ people

- American gay artists

- Artists from Knoxville, Tennessee

- Artists from Manhattan

- People from Greenwich Village

- Harlem Renaissance

- 20th-century American printmakers

- LGBTQ people from Tennessee

- LGBTQ people from New York (state)

- African-American printmakers

- 20th-century African-American painters

- 20th-century American LGBTQ people

- 20th-century American male artists