Beauchamp–Sharp Tragedy

| Beauchamp–Sharp Tragedy | |

|---|---|

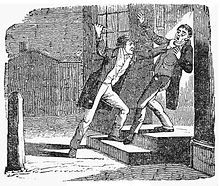

Jereboam O. Beauchamp murders Solomon P. Sharp. | |

| Date | November 7, 1825 c. 2:00 a.m. |

Attack type | Murder by stabbing, assassination |

| Weapon | Knife |

| Victim | Solomon Porcius Sharp |

| Perpetrator | Jereboam Orville Beauchamp |

| Motive | Jereboam avenging the honor of his wife |

| Accused | Anna Cook Beauchamp |

| Verdict | Jereboam: Guilty Anna: Not guilty |

| Charges | Jereboam: Murder Anna: Accessory to murder |

| Sentence | Jereboam: Death by hanging |

The Beauchamp–Sharp Tragedy (sometimes called the Kentucky Tragedy) was the murder of Kentucky legislator Solomon P. Sharp by Jereboam O. Beauchamp. As a young lawyer, Beauchamp had been an admirer of Sharp until Sharp allegedly fathered an illegitimate child with Anna Cooke, a planter's daughter.[a] Sharp denied paternity of the stillborn child. Later, Beauchamp began a relationship with Cooke, who, according to legend, agreed to marry him on the condition that he kill Sharp to avenge her honor.[1][2] Beauchamp and Cooke married in June 1824, and in the early morning of November 7, 1825, Beauchamp murdered Sharp at Sharp's home in Frankfort.[3]

An investigation soon revealed Beauchamp as the killer, and he was apprehended at his home in Glasgow, four days after the murder. He was tried, convicted, and sentenced to death by hanging.[4] He was granted a stay of execution to allow him to write a justification of his actions. Anna Cooke-Beauchamp was tried for complicity in the murder, but was acquitted for lack of evidence. Her devotion to Beauchamp prompted her to stay in his cell with him, where the two attempted a double suicide by drinking laudanum shortly before the execution. This attempt failed. On the morning of the execution, the couple again attempted suicide, this time by stabbing themselves with a knife Anna had smuggled into the cell.[4] When the guards discovered them, Beauchamp was rushed to the gallows, where he was hanged before he could die of his stab wound. He was the first person legally executed in the state of Kentucky. Anna Cooke-Beauchamp died from her wounds shortly before her husband was hanged. In accordance with their wishes, the couple's bodies were positioned in an embrace when buried in the same coffin.

While Beauchamp's primary motive in killing Sharp was to defend the honor of his wife, speculation raged that Sharp's political opponents had instigated the crime. Sharp was a leader of the New Court party during the Old Court – New Court controversy in Kentucky. At least one Old Court partisan alleged that Sharp denied paternity of Cooke's son by claiming the child was a mulatto, the son of a family slave. Whether Sharp made such a claim has never been verified. New Court partisans insisted that the allegation was concocted to stir Beauchamp's anger and provoke him to murder. The Beauchamp–Sharp Tragedy served as the inspiration for numerous literary works, most notably Edgar Allan Poe's unfinished Politian and Robert Penn Warren's World Enough and Time (1950).

Background

[edit]Jereboam Beauchamp was born in Barren County, Kentucky, in 1802. Educated in the school of Dr. Benjamin Thurston, he resolved to study law at age eighteen. While observing the lawyers practicing in Glasgow and Bowling Green, Beauchamp was particularly impressed with the abilities of Solomon P. Sharp. Sharp had twice been elected to the state legislature and had served two terms in the U.S. House of Representatives. Beauchamp became disenchanted with Sharp when, in 1820, a planter's daughter named Anna Cooke claimed Sharp was the father of her child, who was stillborn. Sharp denied paternity, and public opinion favored him. The disgraced Cooke became a recluse at her mother's plantation outside Bowling Green.[5]

Beauchamp's father lived a mile (1.6 km) from Cooke's estate, and the young man wanted to meet her. Beauchamp gradually gained Cooke's trust by visiting under the guise of borrowing books from her library. By summer 1821, the two became friends and began a courtship. Beauchamp was eighteen; Cooke was at least thirty-four. As the courtship progressed, Cooke told Beauchamp that, before they could be married, he would have to kill Solomon Sharp. Beauchamp agreed to her request, expressing his own desire to dispatch Sharp.[6]

The preferred method of honor killing in that day was a duel. Despite Cooke's admonition that Sharp would not accept a challenge to duel, Beauchamp traveled to Frankfort to gain an audience with him. He had recently been named the state's attorney general by Governor John Adair. Beauchamp's account of the interview states that he bullied and humiliated Sharp, that Sharp begged for his life, and that Beauchamp promised to horsewhip Sharp every day until he consented to the duel. For two days, Beauchamp remained in Frankfort, awaiting the duel. He discovered that Sharp had left town, allegedly destined for Bowling Green. Beauchamp rode to Bowling Green, only to find that Sharp was not there and was not expected. Sharp was saved from Beauchamp's first attempt on his life.[7]

Cooke resolved to kill Sharp herself. The next time Sharp was in Bowling Green on business, she sent a letter to him that denounced Beauchamp's actions and claimed she had broken off all contact with him. She asked Sharp to visit her at her plantation before he left town. Sharp questioned the messenger who delivered the letter, as he suspected a trap. He replied to her, saying he would visit at the time appointed. Beauchamp and Cooke awaited the visit, but Sharp never arrived. When Beauchamp rode to Bowling Green to investigate, he learned that Sharp had left for Frankfort two days earlier, leaving substantial unfinished business. Beauchamp concluded that Sharp would eventually have to return to Bowling Green to finish his business there. Determined to await Sharp's return, Beauchamp opened a legal practice in the city. Throughout 1822 and 1823, Beauchamp practiced law and waited for Sharp to return. He never did.[8]

Although Beauchamp had not completed the task she set him, Cooke married the younger man in mid-June 1824.[9] Beauchamp immediately hatched another plot to kill Sharp. He began sending letters – each from a different post office and signed with a pseudonym – requesting Sharp's assistance in settling a land claim and asking when he would again be in Green River country. Sharp finally answered Beauchamp's last letter – mailed in June 1825 – but gave no date for his arrival.[10]

Murder

[edit]

Serving as attorney general in Governor Adair's administration, Sharp had become involved in the Old Court – New Court controversy. The conflict was primarily between debtors who sought relief from their financial burdens after the Panic of 1819 (the New Court, or Relief, faction) and the creditors to whom these obligations were owed (the Old Court, or Anti-Relief, faction). Sharp, who came from humble beginnings, sided with the New Court. By 1825, the New Court faction's power was on the decline. In an attempt to bolster the party's influence, Sharp resigned as attorney general in 1825 to run for a seat in the Kentucky House of Representatives. His opponent was Old Court stalwart John J. Crittenden.[11]

During the campaign, Old Court supporters again raised the issue of Sharp's seduction and abandonment of Anna Cooke. Old Court supporter John Upshaw Waring printed handbills that not only accused Sharp of fathering Cooke's child, but said that Sharp had denied paternity of the child on the grounds that it was a mulatto and the son of a Cooke family slave. Whether Sharp made such a claim has never been determined. Despite the allegations, Sharp won the election.[9]

Word of Sharp's alleged claims soon reached Jereboam Beauchamp, reviving his resolve to kill him. Beauchamp abandoned the idea of killing Sharp honorably in a duel. Instead, he decided to murder him and cast suspicion on his political enemies. To add to the intrigue, Beauchamp plotted to commit the murder on the eve of the General Assembly's opening session.[12]

Beauchamp rode to Frankfort on business, arriving in the city on November 6.[13] Unable to find lodging at the local inns, he rented a room in the private residence of Joel Scott, warden of the state penitentiary.[14] Sometime after midnight, Scott heard a commotion from Beauchamp's room. When he investigated, he found the door latch open and the room unoccupied.[15] Beauchamp, clad in a disguise, buried a set of his clothes near the Kentucky River, then proceeded to Sharp's house.[12] Sharp was not at home, but Beauchamp soon found him at a local hotel.[16] He returned to Sharp's house, concealed himself nearby, and waited for Sharp's return. He observed Sharp re-enter the house about midnight.[16]

Beauchamp approached the house at approximately two o'clock in the morning on November 7, 1825.[13] In his Confession, he described the encounter:

I put on my mask, drew my dagger and proceeded to the door; I knocked three times loud and quick, Colonel Sharp said; "Who's there" - "Covington" I replied, quickly Sharp's foot was heard upon the floor. I saw under the door as he approached without a light. I drew my mask over my face and immediately Colonel Sharp opened the door. I advanced into the room and with my left hand I grasped his right wrist. The violence of the grasp made him spring back and trying to disengage his wrist, he said, "What Covington is this." I replied John A. Covington. "I don't know you," said Colonel Sharp, "I know John W. Covington." Mrs. Sharp appeared at the partition door and then disappeared, seeing her disappear I said in a persuasive tone of voice, "Come to the light Colonel and you will know me," and pulling him by the arm he came readily to the door and still holding his wrist with my left hand I stripped my hat and handkerchief from over my forehead and looked into Sharp's face. He knew me the more readily I imagine, by my long, bush, curly suit of hair. He sprang back and exclaimed in a tone of horror and despair, "Great God it is him," and as he said that he fell on his knees. I let go of his wrist and grasped him by the throat dashing him against the facing of the door and muttered in his face, "die you villain." As I said that I plunged the dagger to his heart.

— Jereboam Beauchamp, Confession of Jereboam O. Beauchamp

The wound severed Sharp's aorta, killing him almost instantly.[13] Sharp's wife Eliza witnessed the entire scene from the top of the stairs in the house, but Beauchamp fled before he could be identified or captured.[13][15] Returning to the site where he had buried a change of clothes, he stripped off his disguise, tied it up with a rock, and sank them in the Kentucky River.[17] In his regular clothes, he returned to his room at Scott's house, where he remained until the following morning.[17]

Arrest

[edit]After learning of the murder, the Kentucky General Assembly authorized the governor to offer a reward of $3,000 for the arrest and conviction of Sharp's killer.[18] The trustees of the city of Frankfort added a reward of $1,000, and friends of Sharp raised an additional $2,000 reward.[15] Suspicion for the killing rested on three men: Beauchamp, Waring, and Patrick H. Darby. During Sharp's 1824 campaign for a seat in the Kentucky House of Representatives, Darby had remarked that, should Sharp be elected, "he would never take his seat and would be as good as a dead man".[18] Waring had made similar threats, boasting that he had already stabbed six men.[19]

A warrant was sworn out for Waring's arrest, but officials soon learned that he was incapacitated, after being shot through both hips the day before Sharp's death. When Darby discovered that he was under suspicion, he began his own investigation into the murder. He traveled to Simpson County where he met Captain John F. Lowe, who told Darby that Beauchamp had related to him detailed plans for the assassination. He also furnished Darby with a letter that contained damaging admissions against Beauchamp.[20]

The first night following the murder, Beauchamp stayed at the home of a relative in Bloomfield.[15] The next day, he traveled to Bardstown, where he spent the night.[15] He lodged with his brother-in-law in Bowling Green on the night of November 9 before returning to his home in Glasgow on November 10.[15] He and Anna had planned to flee to Missouri, but before nightfall, a posse had arrived from Frankfort to arrest him.[21]

He was taken to Frankfort and tried before an examining court, but Commonwealth's Attorney Charles S. Bibb said that he had not yet collected enough evidence to detain him.[22] Beauchamp was released, but agreed to stay in Frankfort for ten days to allow the court to finish its investigation.[18] During this time, Beauchamp wrote letters to John J. Crittenden and George M. Bibb requesting their legal aid in the matter.[22] Neither letter was answered.[22] Meanwhile, Beauchamp's uncle, a state senator, gathered a defense team that included former U.S. Senator John Pope.[22]

During the investigation, unsuccessful attempts were made to match a knife taken from Beauchamp upon his arrest to the type of wound observed on Sharp's body. Efforts to match a footprint found near Sharp's house to Beauchamp were similarly unsuccessful. The posse that arrested Beauchamp had taken a bloody handkerchief from the crime scene, but had lost it on the trip back to Frankfort after the arrest. The best evidence presented by the prosecution was the testimony of Sharp's wife Eliza that she heard the killer's voice and that it was distinctly high-pitched. When given the opportunity to hear Beauchamp's voice, she identified it as that of the killer.[23]

When questioned, Patrick Darby testified that in 1824, Beauchamp had solicited his services in order to bring suit against Sharp for unspecified charges. During their ensuing conversations, Beauchamp had related the story of Sharp's abandonment of Anna Cooke and her child, swearing that he would kill him one day, even if he had to come to Frankfort and shoot him down in the street. The combined testimonies of Eliza Sharp and Patrick Darby were sufficient to persuade the city magistrates to hold Beauchamp for trial during the circuit court's next term, which began in March 1826.[24]

Trial

[edit]Beauchamp was indicted, and his trial began May 8, 1826.[22] Beauchamp pleaded not guilty, but never testified during the trial.[22] Captain Lowe was called to repeat the story he had originally related to Patrick Darby regarding Beauchamp's threats to kill Sharp. He further testified that Beauchamp returned home following the murder waving a red flag and declaring that he had "gained the victory." He also turned over to the court a letter from the Beauchamps regarding the murder. In the letter, Beauchamp maintained his innocence, but told Lowe that his enemies were plotting against him and asked him to testify in his behalf. The letter gave Lowe several talking points to mention if called to testify, some true and some otherwise.[25]

Eliza Sharp repeated her assertion that the murderer's voice was that of Beauchamp. Joel Scott, the warden who gave Beauchamp lodging the night of the murder, testified that he heard Beauchamp leave during the night and return later that night. He also mentioned that Beauchamp was extremely inquisitive about the crime upon being told of it the next morning. The most extensive testimony came from Darby, who recounted his 1824 meeting with Beauchamp. According to Darby, Beauchamp claimed that Sharp offered him and Anna $1,000, a slave girl, and 200 acres (0.81 km2) of land if they would leave him alone. Sharp later reneged on the offer.[26]

Some witnesses maintained that the killer's claim to be John A. Covington was telling. They said that both Sharp and Beauchamp had been acquainted with John W. Covington, and that Beauchamp often mistakenly called him John A. Covington. Other witnesses told of threats they had heard Beauchamp make against Sharp.[27]

Beauchamp's defense team attempted to discredit Patrick Darby by stressing his association with the Old Court and suggesting the murder was politically motivated. They also presented witnesses who testified that they knew of no hostility between Beauchamp and Sharp, and questioned whether Darby and Beauchamp's 1824 meeting ever occurred.[28]

During closing arguments, defense counsel John Pope attempted to discredit Darby; the latter reacted by assaulting one of Pope's co-counselors with a cane.[29] The trial lasted thirteen days, and despite the absence of any physical evidence, including a murder weapon, the jury returned a guilty verdict after only an hour of deliberation on May 19.[22][30] Beauchamp was sentenced to be executed by hanging on June 16, 1826.[31]

During the trial, Anna Beauchamp appealed to John Waring for help on her husband's behalf. She also tried to entice John Lowe to commit perjury and testify on her husband's behalf. Both appeals were denied. On May 20, Anna was examined by two justices of the peace on suspicion of being an accessory to the murder, but was acquitted due to lack of evidence.[32] At her request, Anna was permitted to stay in the cell with Beauchamp .[13]

Pope's request to have the verdict overturned was denied, but the judge granted Beauchamp a stay of execution until July 7 to allow him to produce a written justification of his actions.[33] In it, Beauchamp said he had killed Sharp to defend Anna's honor.[9] Beauchamp had hoped to publish his work before his execution, but the libelous charges it contained – that prosecution witnesses committed perjury and bribery to see him convicted – delayed its publication.[9]

Execution

[edit]The Beauchamps were accused of trying to bribe a guard to let them escape, but this effort failed. They also tried to get a letter to Senator Beauchamp, asking for his help in escaping. A final plea to Governor Desha for another stay of execution was denied on July 5.[33] Later that day, the couple attempted a double suicide by taking large doses of laudanum, but both survived.[13]

On July 7, the morning of Beauchamp's scheduled execution, Anna requested that the guard allow her privacy while she dressed.[34] Anna tried another overdose on laudanum, but was unable to keep it down.[35] She had smuggled a knife into the cell, and the couple attempted another double suicide by stabbing themselves with it.[34] When they were discovered, Anna was taken to the jailer's home and tended to by doctors.[34]

Weakened by his own wounds, Beauchamp was loaded on a cart to be taken to the gallows and hanged before he bled to death. He insisted on seeing his wife before being executed, but doctors told him she was not severely injured and would recover. Beauchamp protested that not being allowed to see his wife was cruel, and the guards consented to take him to her. Upon arriving, he was angered to see that the doctors had lied to him; Anna was too weak even to speak to him. He remained with her until he could no longer feel her pulse. He kissed her lifeless lips and declared "For you I lived — for you I die."[36]

On his way to the gallows, Beauchamp asked to see Patrick Darby, who was among the assembled spectators. Beauchamp smiled and offered his hand, but Darby declined the gesture. Beauchamp publicly denied that Darby had any involvement with the murder, but accused Darby of having lied about the 1824 meeting. Darby denied this accusation of perjury and tried to engage Beauchamp in a discussion about it, hoping he would retract the charge, but the prisoner ordered the cart driver to continue to the gallows.[37]

At the gallows, Beauchamp assured the assembled clergy that he had had a salvation experience on July 6.[38] Too weak to stand, he was held upright by two men while the noose was tied around his neck.[34] At Beauchamp's request, the Twenty-Second Regiment musicians played Bonaparte's Retreat from Moscow while 5,000 spectators watched his execution.[9] It was the first legal hanging in Kentucky's history.[30] Beauchamp's father requested the bodies of his son and daughter-in-law for burial.[30] The two bodies were placed in an embrace in a single coffin, as they had requested.[30] They were buried in Maple Grove Cemetery in Bloomfield, Kentucky.[9] The couple's tombstone was engraved with a poem written by Anna Beauchamp.[34]

Aftermath

[edit]Beauchamp's confession was published in 1826, the same year as The Letters of Ann Cook – the authorship of which is disputed. J. G. Dana and R. S. Thomas also published an edited transcript of Beauchamp's trial.[9] The following year, Sharp's brother, Dr. Leander Sharp, wrote Vindication of the character of the late Col. Solomon P. Sharp to defend Sharp from the charges made in Beauchamp's confession.[9] Patrick Darby threatened to sue Dr. Sharp if the work were published.[39] John Waring threatened Dr. Sharp's life if he published Vindication.[39] All copies of the work were left in the Sharps' home in Frankfort, where they were discovered many years later during a remodel.[39]

Though many regarded Sharp's murder as an honor killing, some New Court partisans charged that Beauchamp had been incited to violence by members of the Old Court party, specifically Patrick Darby. Sharp was thought to be the minority party's choice for Speaker of the House for the 1826 session. By enticing Beauchamp to murder Sharp, the Old Court could remove a political enemy. Sharp's widow Eliza appeared to believe this notion. In an 1826 letter in the New Court Argus of Western America, she referred to Darby as "the chief instigator of the foul murder which has deprived me of all my heart held most dear on earth".[40]

Some Old Court partisans claimed that Governor Desha had offered Beauchamp a pardon if he would implicate Darby and Achilles Sneed, clerk of the Old Court, in his confession. Shortly before his execution, Beauchamp was heard to say he had "been New Court long enough, and would die an Old Court man." Beauchamp had steadfastly identified with the Old Court, and his claim seems to imply that he had at least considered colluding with the New Court powers to secure his pardon. Such a deal is explicitly mentioned in one version of Beauchamp's Confession. Beauchamp ultimately rejected the deal for fear that he would be double-crossed by the New Court, leaving him imprisoned and deprived of the chivalrous motive for his actions.[39]

Darby denied involvement with the murder, claiming that New Court partisans such as Francis P. Blair and Amos Kendall were seeking to defame him.[40] He also countered that Eliza Sharp's letter to the New Court Argus was written by New Court supporters, including Kendall, the newspaper's editor.[40] The claims and counterclaims between the two sides reached such an extreme that an 1826 letter in the New Court Argus suggested that New Court supporters had instigated Sharp's murder in order to blame Old Court partisans and affix a stigma to them.[40]

Darby eventually brought suit for libel against Kendall and Eliza Sharp, as well as Senator Beauchamp and Sharp's brother Leander.[31] Numerous delays and changes of venue prevented any of the suits from ever going to trial.[41] Darby died in December 1829.[41]

In fiction

[edit]The Beauchamp–Sharp Tragedy inspired fictional works, notably Edgar Allan Poe's unfinished play Politian and Robert Penn Warren's World Enough and Time. William Gilmore Simms wrote three works based on the Sharp murder and aftermath: Beauchampe: or The Kentucky Tragedy, A Tale of Passion, Charlemont, and Beauchampe: A Sequel to Charlemonte. Greyslaer: A Romance of the Mohawk by Charles Fenno Hoffman, Octavia Bragaldi by Charlotte Barnes, Sybil by John Savage, and Conrad and Eudora; or, The Death of Alonzo: A Tragedy and Leoni, The Orphan of Venice both by Thomas Holley Chivers, all draw to some degree on the events that surround Sharp's murder.[42]

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]^[a] Sources variously give the name as Anna Cooke, Anna Cook, Ann Cooke, and Ann Cook.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Roberts, Leonard (1968). "Beauchamp and Sharp: A Kentucky Tragedy". Kentucky Folklore Record. 14 (1): 14. ProQuest 1304356503.

- ^ Goldhurst, William (1989). "The New Revenge Tragedy: Comparative Treatments of the Beauchamp Case". The Southern Literary Journal. 22 (1): 117–127. JSTOR 20077977.

- ^ Kimball, William J. (December 1971). "Poe's Politian and the Beauchamp-Sharp Tragedy". Poe Studies. Old Series. 4 (2): 24–27. doi:10.1111/j.1754-6095.1971.tb00166.x.

- ^ a b Srebnick, Amy Gilman (2009). "Review of Murder and Madness: The Myth of the Kentucky Tragedy". The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society. 107 (4): 578–581. JSTOR 23387604.

- ^ Cooke 1998b, pp. 126–127.

- ^ Cooke 1998b, pp. 127–128.

- ^ Cooke 1998b, p. 128–129.

- ^ Cooke 1998b, p. 129.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Whited, p. 404

- ^ Cooke 1998b, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Cooke 1998b, p. 130–131, 134.

- ^ a b Cooke 1998b, p. 136.

- ^ a b c d e f Kleber, p. 63

- ^ O'Malley, p. 43

- ^ a b c d e f O'Malley, p. 44

- ^ a b Cooke 1998b, p. 137.

- ^ a b Cooke 1998b, p. 138.

- ^ a b c L. Johnson, p. 46

- ^ L. Johnson, p. 45

- ^ L. Johnson, pp. 47–48

- ^ O'Malley, p. 45

- ^ a b c d e f g Cooke 1998b, p. 144.

- ^ Bruce 2006, p. 15–16.

- ^ Bruce 2006, p. 16.

- ^ Bruce 2006, pp. 21–25.

- ^ Bruce 2006, p. 21–24.

- ^ Bruce 2006, p. 22–24.

- ^ Bruce 2006, p. 22–23.

- ^ L. Johnson, p. 48

- ^ a b c d O'Malley, p. 47

- ^ a b L. Johnson, p. 49

- ^ Cooke 1998b, pp. 144–145.

- ^ a b Cooke 1998b, p. 145.

- ^ a b c d e Kleber, p. 64

- ^ Bruce 2006, p. 8.

- ^ St. Clair, p. 307

- ^ L. Johnson, p. 54

- ^ Cooke 1998b, p. 146.

- ^ a b c d Johnson, "New Light of Beauchamp's Confession

- ^ a b c d Bruce 2003.

- ^ a b Cooke 1998b, p. 147.

- ^ Whited, pp. 404–405

References

[edit]- Bruce, Dickson D. (2006). The Kentucky Tragedy: A Story of Conflict and Change in Antebellum America. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-3173-2.

- Bruce, Dickson D (September 2003). "The Kentucky tragedy and the transformation of politics in the early American Republic". American Transcendental Quarterly. 17 (3): 181–197. Gale A110266672 ProQuest 222452096.[1]

- Cooke, J.W. (January 1998a). "The Life and Death of Colonel Solomon P. Sharp Part 1: Uprightness and Inventions; Snares and Nets" (PDF). The Filson Club Quarterly. 72 (1): 24–41.

- Cooke, J.W. (April 1998b). "The Life and Death of Colonel Solomon P. Sharp Part 2: A Time to Weep and A Time to Mourn" (PDF). The Filson Club Quarterly. 72 (2): 121–151.

- Johnson, Fred M. (1993). "New Light on Beauchamp's Confession?". Border States Online. Archived from the original on 2014-02-03. Retrieved 2008-02-06.

- Johnson, Lewis Franklin (1922). Famous Kentucky tragedies and trials; a collection of important and interesting tragedies and criminal trials which have taken place in Kentucky. The Baldwin Law Publishing Company. Archived from the original on 2005-03-08. Retrieved 2008-11-22.

- Kleber, John E. (1992). "Beauchamp-Sharp Tragedy". In Kleber, John E (ed.). The Kentucky Encyclopedia. Associate editors: Thomas D. Clark, Lowell H. Harrison, and James C. Klotter. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-1772-0.

- O'Malley, Mimi (2006). "Beauchamp-Sharp Tragedy". It Happened in Kentucky. Globe Pequot. ISBN 0-7627-3853-7. Retrieved 2008-01-24.[permanent dead link]

- St. Clair, Henry (1835). The United States Criminal Calendar. Charles Gaylord. Retrieved 2008-12-09.

- Whited, Stephen R. (2002). "Kentucky Tragedy". In Joseph M. Flora and Lucinda Hardwick MacKethan (ed.). The Companion to Southern Literature: Themes, Genres, Places, People. Associate Editor: Todd W. Taylor. LSU Press. ISBN 0-8071-2692-6. Retrieved 2008-01-24.

Further reading

[edit]- Beauchamp, Jereboam O. (1826). The confession of Jereboam O. Beauchamp : who was hanged at Frankfort, Ky., on the 7th day of July, 1826, for the murder of Col. Solomon P. Sharp. Retrieved 2008-01-10.

- Bruce, Dickson D. (Spring 2002). "Sentimentalism and the Early American Republic: Revisiting the Kentucky Tragedy". Mississippi Quarterly. 55 (2): 185–208.

- Coleman, John Winston (1950). The Beauchamp-Sharp tragedy; an episode of Kentucky history during the middle 1820s. Frankfort, Kentucky: Roberts Print. Co.

- Cooke, J.W. (April 1991). "Portrait of a Murderess: Anna Cook(e) Beauchamp" (PDF). Filson Club History Quarterly. 65 (2): 209–230.

- Kimball, William J. (January 1974). "The 'Kentucky Tragedy': Romance or Politics" (PDF). Filson Club History Quarterly. 48: 16–26.

- Beauchamp, Jereboam O. (1850). The life of Jeroboam O. Beauchamp : who was hung at Frankfort, Kentucky, for the murder of Col. Solomon P. Sharp. Frankfort, Kentucky: O'Neill & D'Unger.

- Schoenbachler, Matthew G. Murder and Madness: The Myth of the Kentucky Tragedy Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2009.

- Sharp, Leander J. (1827). Vindication of the Character of the Late Col. Solomon P. Sharp. Frankfort, Kentucky: Amos Kendall and Co. Archived from the original on 2014-02-01. Retrieved 2013-04-02., scanned version online, Kentucky Digital Library

- Thies, Clifford F. (2007-02-07). "Murder and Inflation: the Kentucky Tragedy". Ludwig von Mises Institute. Retrieved 2008-01-24.

- Works inspired by the Beauchamp–Sharp Tragedy

- Barnes, Charlotte (1848). Octavia Bragaldi. E.H. Butler.

- Chivers, Thomas Holley (1834). Conrad and Eudora, or The Death of Alonzo.

- Hoffman, Charles Fenno (1840). Greyslaer: A Romance of the Mohawk. R. Bentley. Retrieved 2008-01-26.

- Poe, Edgar Allan (1911). "Scenes from 'Politan'". The Complete Poems of Edgar Allan Poe. Houghton Mifflin Company. pp. 40–59. Retrieved 2008-01-26.

- Savage, John (1865). Sybil. J.B. Kirker.

- Simms, William Gilmore (1843). Beauchampe: or The Kentucky Tragedy, A Tale of Passion. Bruce and Wyld.

- Simms, William Gilmore (1885). Beauchampe: Or, The Kentucky Tragedy, a Sequel to Charlemont. Bedford, Clark. Retrieved 2008-01-26.

- Simms, William Gilmore (1885). Charlemont: Or, The Pride of the Village. A Tale of Kentucky. Belford, Clark. Retrieved 2008-01-26.

- Warren, Robert Penn (1950). World Enough and Time. Vintage Books. ISBN 0-394-72818-1.

External links

[edit]- Jereboam O. Beauchamp at Find a Grave

- Ann Cooke Beauchamp at Find a Grave

- Solomon Porcius Sharp at Find a Grave