Beamish Museum

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2022) |

| |

| Established | 1972 |

|---|---|

| Location | Beamish, Stanley, County Durham, England |

| Coordinates | 54°52′55″N 1°39′30″W / 54.88194°N 1.65833°W |

| Type | Open-air living museum |

| Collection size | 304,000+ objects |

| Visitors | 801,756 in 2023[1] |

| CEO | Rhiannon Hiles |

| Website | www |

Beamish Museum is the first regional open-air museum, in England,[2] located at Beamish, near the town of Stanley, in County Durham, England. Beamish pioneered the concept of a living museum.[3] By displaying duplicates or replaceable items, it was also an early example of the now commonplace practice of museums allowing visitors to touch objects.[3]

The museum's guiding principle is to preserve an example of everyday life in urban and rural North East England at the climax of industrialisation in the early 20th century. Much of the restoration and interpretation is specific to the late Victorian and Edwardian eras, together with portions of countryside under the influence of Industrial Revolution from 1825. On its 350 acres (140 ha) estate it uses a mixture of translocated, original and replica buildings, a large collection of artefacts, working vehicles and equipment, as well as livestock and costumed interpreters.

The museum has received a number of awards since it opened to visitors in 1972 and has influenced other living museums.[citation needed] It is an educational resource, and also helps to preserve some traditional and rare north-country livestock breeds.

History

[edit]Genesis

[edit]In 1958, days after starting as director of the Bowes Museum, inspired by Scandinavian folk museums, and realising the North East's traditional industries and communities were disappearing, Frank Atkinson[2] presented a report to Durham County Council urging that a collection of items of everyday history on a large scale should begin as soon as possible, so that eventually an open air museum could be established. As well as objects, Atkinson was also aiming to preserve the region's customs and dialect. He stated the new museum should "attempt to make the history of the region live" and illustrate the way of life of ordinary people. He hoped the museum would be run by, be about and exist for the local populace, desiring them to see the museum as theirs, featuring items collected from them.[4]

Fearing it was now almost too late, Atkinson adopted a policy of "unselective collecting" — "you offer it to us and we will collect it."[4][5][6] Donations ranged in size from small items to locomotives and shops, and Atkinson initially took advantage of a surplus of space available in the 19th-century French chateau-style building housing the Bowes Museum to store items donated for the open air museum.[3] With this space soon filled, a former British Army tank depot at Brancepeth was taken over, although in just a short time its entire complement of 22 huts and hangars had been filled, too.[4][6]

In 1966, a working party was established to set up a museum "for the purpose of studying, collecting, preserving and exhibiting buildings, machinery, objects and information illustrating the development of industry and the way of life of the north of England", and it selected Beamish Hall, having been vacated by the National Coal Board, as a suitable location.[3]

Establishment and expansion

[edit]In August 1970, with Atkinson appointed as its first full-time director together with three staff members, the museum was first established by moving some of the collections into the hall. In 1971, an introductory exhibition, "Museum in the Making" opened at the hall.[4][7]

The museum was opened to visitors on its current site for the first time in 1972, with the first translocated buildings (the railway station and colliery winding engine) being erected the following year.[7] The first trams began operating on a short demonstration line in 1973.[8] The Town station was formally opened in 1976,[9] the same year the reconstruction of the colliery winding engine house was completed,[10] and the miners' cottages were relocated.[11] Opening of the drift mine as an exhibit followed in 1979.[4]

In 1975 the museum was visited by the Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, and by Anne, Princess Royal, in 2002.[4] In 2006, as the Grand Master of the United Grand Lodge of England, The Duke of Kent visited, to open the town masonic lodge.[4]

With the Co-op having opened in 1984,[12] the town area was officially opened in 1985.[13] The pub had opened in the same year,[14] with Ravensworth Terrace having been reconstructed from 1980 to 1985.[15] The newspaper branch office had also been built in the mid-1980s.[16] Elsewhere, the farm on the west side of the site (which became Home Farm) opened in 1983.[17] The present arrangement of visitors entering from the south was introduced in 1986.[6][18]

At the beginning of the 1990s, further developments in the Pit Village were opened, the chapel in 1990,[19] and the board school in 1992.[20] The whole tram circle was in operation by 1993.[8] Further additions to the Town came in 1994 with the opening of the sweet shop and motor garage,Beamish Museum 2014[21] followed by the bank in 1999.[22] The first Georgian component of the museum arrived when Pockerley Old Hall opened in 1995,[23] followed by the Pockerley Waggonway in 2001.[24]

In the early 2000s two large modern buildings were added, to augment the museum's operations and storage capacity - the Regional Resource Centre on the west side opened in 2001, followed by the Regional Museums Store next to the railway station in 2002. Due to its proximity, the latter has been cosmetically presented as Beamish Waggon and Iron Works. Additions to display areas came in the form of the Masonic lodge (2006)[25] and the Lamp Cabin in the Colliery (2009).[26] In 2010, the entrance building and tea rooms were refurbished.[4]

Into the 2010s, further buildings were added - the fish and chip shop (opened 2011)[27] band hall (opened 2013)[28] and pit pony stables (built 2013/14)[29] in the Pit Village, plus a bakery (opened 2013)[16] and chemist and photographers (opened 2016)[30] being added to the town. St Helen's Church, in the Georgian landscape, opened in November 2015.[31]

Remaking Beamish

[edit]A major development, named 'Remaking Beamish', was approved by Durham County Council in April 2016, with £10.7m having been raised from the Heritage Lottery Fund and £3.3m from other sources.[32]

As of September 2022, new exhibits as part of this project have included a quilter's cottage, a welfare hall, 1950s terrace, recreation park, bus depot, and 1950s farm (all discussed in the relevant sections of this article). The coming years will see replicas of aged miners' homes from South Shields,[32] a cinema from Ryhope,[32] and social housing will feature a block of four relocated Airey houses, prefabricated concrete homes originally designed by Sir Edwin Airey, which previously stood in Kibblesworth. Then-recently vacated and due for demolition, they were instead offered to the museum by The Gateshead Housing Company and accepted in 2012.[33]

Museum site

[edit]The approximately 350-acre (1.4 km2) current site,[34] once belonging to the Eden and Shafto families, is a basin-shaped steep-sided valley with woodland areas, a river, some level ground and a south-facing aspect.[6]

Visitors enter the site through an entrance arch formed by a steam hammer, across a former opencast mining site and through a converted stable block (from Greencroft, near Lanchester, County Durham).[6][18]

Visitors can navigate the site via assorted marked footpaths, including adjacent (or near to) the entire tramway oval. According to the museum, it takes 20 minutes to walk at a relaxed pace from the entrance to the town. The tramway oval serves as both an exhibit and as a free means of transport around the site for visitors, with stops at the entrance (south), Home Farm (west), Pockerley (east) and the Town (north). Visitors can also use the museum's buses as a free form of transport between various parts of the museum.[34] Although visitors can also ride on the Town railway and Pockerley Waggonway, these do not form part of the site's transport system (as they start and finish from the same platforms).

Governance

[edit]Beamish was the first English museum to be financed and administered by a consortium of county councils (Cleveland, Durham, Northumberland and Tyne and Wear)[2] The museum is now operated as a registered charity, but continues to receive support from local authorities - Durham County Council, Sunderland City Council, Gateshead Council, South Tyneside Council and North Tyneside Council.[35] The supporting Friends of Beamish organisation was established in 1968.[36] Frank Atkinson retired as director in 1987.[4] The museum has been 96% self-funding for some years (mainly from admission charges).[6][18]

Sections of the museum

[edit]1913

[edit]

The town area, officially opened in 1985, depicts chiefly Victorian buildings in an evolved urban setting of 1913.[37]

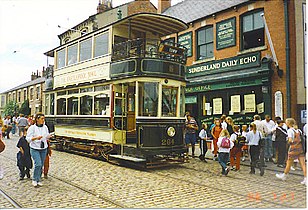

Tramway

[edit]The Beamish Tramway is 1.5 miles (2.4 km) long, with four passing loops.[38] The line makes a circuit of the museum site forming an important element of the visitor transportation system.[39][40]

The first trams began operating on a short demonstration line in 1973, with the whole circle in operation by 1993.[8] It represents the era of electric powered trams, which were being introduced to meet the needs of growing towns and cities across the North East from the late 1890s, replacing earlier horse drawn systems.[38]

Bakery

[edit]Presented as Joseph Herron, Baker & Confectioner, the bakery was opened in 2013 and features working ovens which produce food for sale to visitors. A two-storey curved building, only the ground floor is used as the exhibit. A bakery has been included to represent the new businesses which sprang up to cater for the growing middle classes - the ovens being of the modern electric type which were growing in use. The building was sourced from Anfield Plain (which had a bakery trading as Joseph Herron), and was moved to Beamish in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The frontage features a stained glass from a baker's shop in South Shields.[16] It also uses fittings from Stockton-on-Tees.[41]

Motor garage

[edit]Presented as Beamish Motor & Cycle Works, the motor garage opened in 1994. Reflecting the custom nature of the early motor trade, where only one in 232 people owned a car in 1913, the shop features a showroom to the front (not accessible to visitors), with a garage area to the rear, accessed via the adjacent archway. The works is a replica of a typical garage of the era. Much of the museum's car, motorcycle and bicycle collection, both working and static, is stored in the garage.[21] The frontage has two storeys, but the upper floor is only a small mezzanine and is not used as part of the display.

Department Store

[edit]

Presented as the Annfield Plain Industrial Co-operative Society Ltd, (but more commonly referred to as the Anfield Plain Co-op Store) this department store opened in 1984, and was relocated to Beamish from Annfield Plain in County Durham. The Annfield Plain co-operative society was originally established in 1870, with the museum store stocking various products from the Co-operative Wholesale Society (CWS), established 1863. A two-storey building, the ground floor comprises the three departments - grocery, drapery and hardware; the upper floor is taken up by the tea rooms (accessed from Redman Park via a ramp to the rear). Most of the items are for display only, but a small amount of goods are sold to visitors.[12] The store features an operational cash carrier system, of the Lamson Cash Ball design - common in many large stores of the era, but especially essential to Co-ops, where customer's dividends had to be logged.[12][42][43]

Ravensworth Terrace

[edit]Ravensworth Terrace is a row of terraced houses, presented as the premises and living areas of various professionals. Representing the expanding housing stock of the era, it was relocated from its original site on Bensham Bank, having been built for professionals and tradesmen between 1830 and 1845. Original former residents included painter John Wilson Carmichael and Gateshead mayor Alexander Gillies. Originally featuring 25 homes, the terrace was to be demolished when the museum saved it in the 1970s, reconstructing six of them on the Town site between 1980 and 1985. They are two storey buildings, with most featuring display rooms on both floors - originally the houses would have also housed a servant in the attic. The front gardens are presented in a mix of the formal style, and the natural style that was becoming increasingly popular.[15]

No. 2 is presented as the home of Miss Florence Smith, a music teacher, with old fashioned mid-Victorian furnishings as if inherited from her parents. No. 3 & 4 is presented as the practice and home respectively (with a knocked through door) of dentist J. Jones - the exterior nameplate having come from the surgery of Mr. J. Jones in Hartlepool. Representing the state of dental health at the time, it features both a check-up room and surgery for extraction, and a technicians room for creating dentures - a common practice at the time being the giving to daughters a set on their 21st birthday, to save any future husband the cost at a later date. His home is presented as more modern than No.2, furnished in the Edwardian style the modern day utilities of an enamelled bathroom with flushing toilet, a controllable heat kitchen range and gas cooker. No. 5 is presented as a solicitor's office, based on that of Robert Spence Watson, a Quaker from Newcastle. Reflecting the trade of the era, downstairs is laid out as the partner's or principal office, and the general or clerk's office in the rear. Included is a set of books sourced from ER Hanby Holmes, who practised in Barnard Castle.[15]

Pub

[edit]Presented as The Sun Inn, the pub opened in the town in 1985.[44] It had originally stood in Bondgate in Bishop Auckland, and was donated to the museum by its final owners, the Scottish and Newcastle Breweries. Originally a "one-up one down" cottage, the earliest ownership has been traced to James Thompson, on 21 January 1806. Known as The Tiger Inn until the 1850s, from 1857 to 1899 under the ownership of the Leng family, it flourished under the patronage of miners from Newton Cap and other collieries. Latterly run by Elsie Edes, it came under brewery ownership in the 20th Century when bought by S&N antecedent, James Deuchar Ltd. The pub is fully operational,[45] and features both a front and back bar, the two storeys above not being part of the exhibit. The interior decoration features the stuffed racing greyhound, Jake's Bonny Mary, which won nine trophies before being put on display in The Gerry in White le Head near Tantobie.[14]

Town stables

[edit]

Reflecting the reliance on horses for a variety of transport needs in the era, the town features a centrally located stables, situated behind the sweet shop, with its courtyard being accessed from the archway next to the pub. It is presented as a typical jobmaster's yard, with stables and a tack room in the building on its north side. A small, brick built open air, carriage shed is sited on the back of the printworks building. On the east side of the courtyard is a much larger metal shed (utilising iron roof trusses from Fleetwood), arranged mainly as carriage storage, but with a blacksmith's shop in the corner. The building on the west side of the yard is not part of any display. The interior fittings for the harness room came from Callaly Caste. Many of the horses and horse-drawn vehicles used by the museum are housed in the stables and sheds.[46]

Printer, stationer and newspaper branch office

[edit]

Presented as the Beamish Branch Office of the Northern Daily Mail and the Sunderland Daily Echo,[47] the two storey replica building was built in the mid-1980s and represents the trade practices of the era. Downstairs, on the right, is the branch office, where newspapers would be sold directly and distributed to local newsagents and street vendors, and where orders for advertising copy would be taken. Supplementing it is a stationer's shop on the left hand side, with both display items and a small number of gift items on public sale. Upstairs is a jobbing printers workshop, which would not produce the newspapers, but would instead print leaflets, posters and office stationery. Split into a composing area and a print shop, the shop itself has a number of presses - a Columbian built in 1837 by Clymer and Dixon, an Albion dating back to 1863, an Arab Platen of c. 1900, and a Wharfedale flat bed press, built by Dawson & Son in around 1870. Much of the machinery was sourced from the print works of Jack Ascough's of Barnard Castle.[16] Many of the posters seen around the museum are printed in the works, with the operation of the machinery being part of the display.

Sweet shop

[edit]Presented as Jubilee Confectioners, the two storey sweet shop opened in 1994 and is meant to represent the typical family run shops of the era, with living quarters above the shop (the second storey not being part of the display). To the front of the ground floor is a shop, where traditional sweets and chocolate (which was still relatively expensive at the time) are sold to visitors, while in the rear of the ground floor is a manufacturing area where visitors can view the techniques of the time (accessed via the arched walkway on the side of the building). The sweet rollers were sourced from a variety of shops and factories.Beamish Museum 2014

Bank

[edit]Presented as a branch of Barclays Bank (Barclay & Company Ltd) using period currency, the bank opened in 1999. It represents the trend of the era when regional banks were being acquired and merged into national banks such as Barclays, formed in 1896. Built to a three-storey design typical of the era, and featuring bricks in the upper storeys sourced from Park House, Gateshead, the Swedish imperial red shade used on the ground floor frontage is intended to represent stability and security. On the ground floor are windows for bank tellers, plus the bank manager's office. Included in a basement level are two vaults. The upper two storeys are not part of the display.[22] It features components sourced from Southport and Gateshead

Masonic Hall

[edit]The Masonic Hall opened in 2006, and features the frontage from a former masonic hall sited in Park Terrace, Sunderland. Reflecting the popularity of the masons in North East England, as well as the main hall, which takes up the full height of the structure, in a small two story arrangement to the front of the hall is also a Robing Room and the Tyler's Room on the ground floor, and a Museum Room upstairs, featuring display cabinets of masonic regalia donated from various lodges.[25] Upstairs is also a class room, with large stained glass window.

Chemist and photographer

[edit]Presented as W Smith's Chemist and JR & D Edis Photographers, a two-storey building housing both a chemist and photographers shops under one roof opened on 7 May 2016 and represents the growing popularity of photography in the era, with shops often growing out of or alongside chemists, who had the necessary supplies for developing photographs. The chemist features a dispensary, and equipment from various shops including John Walker, inventor of the friction match. The photographers features a studio, where visitors can dress in period costume and have a photograph taken. The corner building is based on a real building on Elvet Bridge in Durham City, opposite the Durham Marriot Hotel (the Royal County), although the second storey is not part of the display. The chemist also sells aerated water (an early form of carbonated soft drinks) to visitors, sold in marble-stopper sealed Codd bottles (although made to a modern design to prevent the safety issue that saw the original bottles banned: children were smashing the bottles to retrieve the glass marble).[30][48] Aerated waters grew in popularity in the era, due to the need for a safe alternative to water, and the temperance movement - being sold in chemists due to the perception they were healthy in the same way mineral waters were.[49]

Costing around £600,000 and begun on 18 August 2014, the building's brickwork and timber was built by the museum's own staff and apprentices, using Georgian bricks salvaged from demolition works to widen the A1. Unlike previous buildings built on the site, the museum had to replicate rather than relocate this one due to the fact that fewer buildings are being demolished compared to the 1970s, and in any case it was deemed unlikely one could be found to fit the curved shape of the plot. The studio is named after a real business run by John Reed Edis and his daughter Daisy. Mr Edis, originally at 27 Sherburn Road, Durham, in 1895, then 52 Saddler Street from 1897. The museum collection features several photographs, signs and equipment from the Edis studio. The name for the chemist is a reference to the business run by William Smith, who relocated to Silver Street, near the original building, in 1902. According to records, the original Edis company had been supplied by chemicals from the original (and still extant) Smith business.[30][48]

Redman Park

[edit]Redman Park is a small lawned space with flower borders, opposite Ravensworth Terrace. Its centrepiece is a Victorian bandstand sourced from Saltwell Park, where it stood on an island in the middle of a lake. It represents the recognised need of the time for areas where people could relax away from the growing industrial landscape.[50]

Other

[edit]Included in the Town are drinking fountains and other period examples of street furniture. In between the bank and the sweet shop is a combined tram and bus waiting room and public convenience.

Unbuilt

[edit]When construction of the Town began, the projected town plan incorporated a market square and buildings including a gas works, fire station, ice cream parlour (originally the Central Cafe at Consett), a cast iron bus station from Durham City, school, public baths and a fish and chip shop.[51]

Railway station

[edit]

East of the Town is the Railway Station, depicting a typical small passenger and goods facility operated by the main railway company in the region at the time, the North Eastern Railway (NER). A short running line extends west in a cutting around the north side of the Town itself, with trains visible from the windows of the stables.[52] It runs for a distance of 1⁄4 mile - the line used to connect to the colliery sidings until 1993 when it was lifted between the town and the colliery so that the tram line could be extended. During 2009 the running line was relaid so that passenger rides could recommence from the station during 2010.

Rowley station

[edit]Representing passenger services is Rowley Station, a station building on a single platform, opened in 1976, having been relocated to the museum from the village of Rowley near Consett, just a few miles from Beamish.[52]

The original Rowley railway station was opened in 1845 (as Cold Rowley, renamed Rowley in 1868) by the NER antecedent, the Stockton and Darlington Railway, consisting of just a platform. Under NER ownership, as a result of increasing use, in 1873 the station building was added. As demand declined, passenger service was withdrawn in 1939, followed by the goods service in 1966. Trains continued to use the line for another three years before it closed, the track being lifted in 1970. Although in a state of disrepair, the museum acquired the building, dismantling it in 1972, being officially unveiled in its new location by railway campaigner and poet, Sir John Betjeman.[9]

The station building is presented as an Edwardian station, lit by oil lamp, having never been connected to gas or electricity supplies in its lifetime. It features both an open waiting area and a visitor accessible waiting room (western half), and a booking and ticket office (eastern half), with the latter only visible from a small viewing entrance. Adorning the waiting room is a large tiled NER route map.[52]

Signal box

[edit]The signal box dates from 1896, and was relocated from Carrhouse near Consett.[52] It features assorted signalling equipment, basic furnishings for the signaller, and a lever frame, controlling the stations numerous points, interlocks and semaphore signals. The frame is not an operational part of the railway, the points being hand operated using track side levers. Visitors can only view the interior from a small area inside the door.

Goods shed

[edit]The goods shed is originally from Alnwick.[52] The goods area represents how general cargo would have been moved on the railway, and for onward transport. The goods shed features a covered platform where road vehicles (wagons and carriages) can be loaded with the items unloaded from railway vans. The shed sits on a triangular platform serving two sidings, with a platform mounted hand-crane, which would have been used for transhipment activity (transfer of goods from one wagon to another, only being stored for a short time on the platform, if at all).

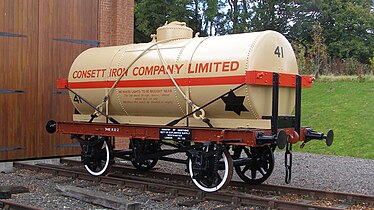

Coal yard

[edit]The coal yard represents how coal would have been distributed from incoming trains to local merchants - it features a coal drop which unloads railway wagons into road going wagons below. At the road entrance to the yard is a weighbridge (with office) and coal merchant's office - both being appropriately furnished with display items, but only viewable from outside.

The coal drop was sourced from West Boldon, and would have been a common sight on smaller stations. The weighbridge came from Glanton, while the coal office is from Hexham.[52]

Bridges and level crossing

[edit]The station is equipped with two footbridges, a wrought iron example to the east having come from Howden-le-Wear, and a cast iron example to the west sourced from Dunston.[52] Next to the western bridge, a roadway from the coal yard is presented as crossing the tracks via a gated level crossing (although in reality the road goes nowhere on the north side).

Waggon and Iron Works

[edit]

Dominating the station is the large building externally presented as Beamish Waggon and Iron Works, estd 1857. In reality this is the Regional Museums Store (see below), although attached to the north side of the store are two covered sidings (not accessible to visitors), used to service and store the locomotives and stock used on the railway.

Other

[edit]A corrugated iron hut adjacent to the 'iron works' is presented as belonging to the local council, and houses associated road vehicles, wagons and other items.

Fairground

[edit]Adjacent to the station is an events field and fairground with a set of Frederick Savage built steam powered Gallopers dating from 1893.

Colliery

[edit]Presented as Beamish Colliery (owned by James Joicey & Co., and managed by William Severs), the colliery represents the coal mining industry which dominated the North East for generations - the museum site is in the former Durham coalfield, where 165,246 men and boys worked in 304 mines in 1913. By the time period represented by Beamish's 1900s era, the industry was booming - production in the Great Northern Coalfield had peaked in 1913, and miners were relatively well paid (double that of agriculture, the next largest employer), but the work was dangerous. Children could be employed from age 12 (the school leaving age), but could not go underground until 14.[53]

Deep mine

[edit]

Dominating the colliery site are the above ground structures of a deep (i.e. vertical shaft) mine - the brick built Winding Engine House, and the red painted wooden Heapstead. These were relocated to the museum (which never had its own vertical shaft), the winding house coming from Beamish Chophill Colliery, and the Heapstead from Ravensworth Park Mine in Gateshead. The winding engine and its enclosing house are both listed.[10]

The winding engine was the source of power for hauling miners, equipment and coal up and down the shaft in a cage, the top of the shaft being in the adjacent heapstead, which encloses the frame holding the wheel around which the hoist cable travels. Inside the Heapstead, tubs of coal from the shaft were weighed on a weighbridge, then tipped onto jigging screens, which sifted the solid lumps from small particles and dust - these were then sent along the picking belt, where pickers, often women, elderly or disabled people or young boys (i.e. workers incapable of mining), would separate out unwanted stone, wood and rubbish. Finally, the coal was tipped onto waiting railway wagons below, while the unwanted waste sent to the adjacent heap by an external conveyor.[10]

Chophill Colliery was closed by the National Coal Board in 1962, but the winding engine and tower were left in place. When the site was later leased, Beamish founder Frank Atkinson intervened to have both spot listed to prevent their demolition. After a protracted and difficult process to gain the necessary permissions to move a listed structure, the tower and engine were eventually relocated to the museum, work being completed in 1976. The winding engine itself is the only surviving example of the type which was once common, and was still in use at Chophill upon its closure. It was built in 1855 by J&G Joicey of Newcastle, to an 1800 design by Phineas Crowther.[10]

Inside the winding engine house, supplementing the winding engine is a smaller jack engine, housed in the rear. These were used to lift heavy equipment, and in deep mines, act as a relief winding engine.[10]

Outdoors, next to the Heapstead, is a sinking engine, mounted on red bricks. Brought to the museum from Silksworth Colliery in 1971, it was built by Burlington's of Sunderland in 1868 and is the sole surviving example of its kind. Sinking engines were used for the construction of shafts, after which the winding engine would become the source of hoist power. It is believed the Silksworth engine was retained because it was powerful enough to serve as a backup winding engine, and could be used to lift heavy equipment (i.e. the same role as the jack engine inside the winding house).[54]

Drift mine

[edit]The Mahogany Drift Mine is original to Beamish, having opened in 1855 and after closing, was brought back into use in 1921 to transport coal from Beamish Park Drift to Beamish Cophill Colliery.[55] It opened as a museum display in 1979.[4] Included in the display is the winding engine and a short section of trackway used to transport tubs of coal to the surface, and a mine office. Visitor access into the mine shaft is by guided tour.[55]

Lamp cabin

[edit]The Lamp Cabin opened in 2009, and is a recreation of a typical design used in collieries to house safety lamps, a necessary piece of equipment for miners although were not required in the Mahogany Drift Mine, due to it being gas-free. The building is split into two main rooms; in one half, the lamp cabin interior is recreated, with a collection of lamps on shelves, and the system of safety tokens used to track which miners were underground. Included in the display is a 1927 Hailwood and Ackroyd lamp-cleaning machine sourced from Morrison Busty Colliery in Annfield Plain. In the second room is an educational display, i.e., not a period interior.[26]

Colliery railways

[edit]

The colliery features both a standard gauge railway, representing how coal was transported to its onward destination, and narrow-gauge typically used by Edwardian collieries for internal purposes. The standard gauge railway is laid out to serve the deep mine - wagons being loaded by dropping coal from the heapstead - and runs out of the yard to sidings laid out along the northern-edge of the Pit Village.[56]

The standard gauge railway has two engine sheds in the colliery yard, the smaller brick, wood and metal structure being an operational building; the larger brick-built structure is presented as Beamish Engine Works, a reconstruction of an engine shed formerly at Beamish 2nd Pit. Used for locomotive and stock storage, it is a long, single track shed featuring a servicing pit for part of its length. Visitors can walk along the full length in a segregated corridor.[56] A third engine shed in brick (lower half) and corrugated iron has been constructed at the southern end of the yard, on the other side of the heapstead to the other two sheds, and is used for both narrow and standard gauge vehicles (on one road), although it is not connected to either system - instead being fed by low-loaders and used for long-term storage only.[57]

The narrow gauge railway is serviced by a corrugate iron engine shed, and is being expanded to eventually encompass several sidings.[56]

There are a number of industrial steam locomotives (including rare examples by Stephen Lewin from Seaham and Black, Hawthorn & Co) and many chaldron wagons, the region's traditional type of colliery railway rolling stock, which became a symbol of Beamish Museum.[58] The locomotive Coffee Pot No 1 is often in steam during the summer.

Other

[edit]On the south eastern corner of the colliery site is the Power House, brought to the museum from Houghton Colliery. These were used to store explosives.[59]

Pit Village

[edit]Alongside the colliery is the pit village, representing life in the mining communities that grew alongside coal production sites in the North East, many having come into existence solely because of the industry, such as Seaham Harbour, West Hartlepool, Esh Winning and Bedlington.[60]

Miner's Cottages

[edit]

The row of six miner's cottages in Francis Street represent the tied-housing provided by colliery owners to mine workers. Relocated to the museum in 1976, they were originally built in the 1860s in Hetton-le-Hole by Hetton Coal Company. They feature the common layout of a single-storey with a kitchen to the rear, the main room of the house, and parlour to the front, rarely used (although it was common for both rooms to be used for sleeping, with disguised folding "dess" beds common), and with children sleeping in attic spaces upstairs. In front are long gardens, used for food production, with associated sheds. An outdoor toilet and coal bunker were in the rear yards, and beyond the cobbled back lane to their rear are assorted sheds used for cultivation, repairs and hobbies. Chalkboard slates attached to the rear wall were used by the occupier to tell the mine's "knocker up" when they wished to be woken for their next shift.[11]

No.2 is presented as a Methodist family's home, featuring good quality "Pitman's mahogany" furniture; No.3 is presented as occupied by a second generation well off Irish Catholic immigrant family featuring many items of value (so they could be readily sold off in times of need) and an early 1890s range; No.3 is presented as more impoverished than the others with just a simple convector style Newcastle oven, being inhabited by a miner's widow allowed to remain as her son is also a miner, and supplementing her income doing laundry and making/mending for other families. All the cottages feature examples of the folk art objects typical of mining communities. Also included in the row is an office for the miner's paymaster.[11] In the rear alleyway of the cottages is a communal bread oven, which were commonplace until miner's cottages gradually obtained their own kitchen ranges. They were used to bake traditional breads such as the Stottie, as well as sweet items, such as tea cakes. With no extant examples, the museum's oven had to be created from photographs and oral history.[61]

School

[edit]

The school opened in 1992, and represents the typical board school in the educational system of the era (the stone built single storey structure being inscribed with the foundation date of 1891, Beamish School Board), by which time attendance at a state approved school was compulsory, but the leaving age was 12, and lessons featured learning by rote and corporal punishment. The building originally stood in East Stanley, having been set up by the local school board, and would have numbered around 150 pupils. Having been donated by Durham County Council, the museum now has a special relationship with the primary school that replaced it. With separate entrances and cloakrooms for boys and girls at either end, the main building is split into three class rooms (all accessible to visitors), connected by a corridor along the rear. To the rear is a red brick bike shed, and in the playground visitors can play traditional games of the era.[20]

Chapel

[edit]

Pit Hill Chapel opened in 1990, and represents the Wesleyan Methodist tradition which was growing in North East England, with the chapels used for both religious worship and as community venues, which continue in its role in the museum display. Opened in the 1850s, it originally stood not far from its present site, having been built in what would eventually become Beamish village, near the museum entrance. A stained glass window of The Light of The World by William Holman Hunt came from a chapel in Bedlington. A two handled Love Feast Mug dates from 1868, and came from a chapel in Shildon Colliery. On the eastern wall, above the elevated altar area, is an angled plain white surface used for magic lantern shows, generated using a replica of the double-lensed acetylene gas powered lanterns of the period, mounted in the aisle of the main seating area. Off the western end of the hall is the vestry, featuring a small library and communion sets from Trimdon Colliery and Catchgate.[19][62]

Fish bar

[edit]

Presented as Davey's Fried Fish & Chip Potato Restaurant, the fish and chip shop opened in 2011, and represents the typical style of shop found in the era as they were becoming rapidly popular in the region - the brick built Victorian style fryery would most often have previously been used for another trade, and the attached corrugated iron hut serves as a saloon with tables and benches, where customers would eat and socialise. Featuring coal fired ranges using beef-dripping, the shop is named in honour of the last coal fired shop in Tyneside, in Winlaton Mill, and which closed in 2007. Latterly run by brothers Brian and Ramsay Davy, it had been established by their grandfather in 1937. The serving counter and one of the shop's three fryers, a 1934 Nuttal, came from the original Davy shop. The other two fryers are a 1920s Mabbott used near Chester until the 1960s, and a GW Atkinson New Castle Range, donated from a shop in Prudhoe in 1973. The latter is one of only two known late Victorian examples to survive. The decorative wall tiles in the fryery came to the museum in 1979 from Cowes Fish and Game Shop in Berwick upon Tweed. The shop also features both an early electric and hand-powered potato rumblers (cleaners), and a gas powered chip chopper built around 1900. Built behind the chapel, the fryery is arranged so the counter faces the rear, stretching the full length of the building. Outside is a brick built row of outdoor toilets. Supplementing the fish bar is the restored Berriman's mobile chip van, used in Spennymoor until the early 1970s.[27]

Band hall

[edit]The Hetton Silver Band Hall opened in 2013, and features displays reflecting the role colliery bands played in mining life. Built in 1912, it was relocated from its original location in South Market Street, Hetton-le-Hole, where it was used by the Hetton Silver Band, founded in 1887. They built the hall using prize money from a music competition, and the band decided to donate the hall to the museum after they merged with Broughtons Brass Band of South Hetton (to form the Durham Miners' Association Brass Band). It is believed to be the only purpose built band hall in the region.[28] The structure consists of the main hall, plus a small kitchen to the rear; as part of the museum it is still used for performances.

Pit pony stables

[edit]The Pit Pony Stables were built in 2013/14, and house the museum's pit ponies. They replace a wooden stable a few metres away in the field opposite the school (the wooden structure remaining). It represents the sort of stables that were used in drift mines (ponies in deep mines living their whole lives underground), pit ponies having been in use in the north east as late as 1994, in Ellington Colliery. The structure is a recreation of an original building that stood at Rickless Drift Mine, between High Spen and Greenside; it was built using a yellow brick that was common across the Durham coalfield.[29]

Other

[edit]Doubling as one of the museum's refreshment buildings, Sinker's Bait Cabin represents the temporary structures that would have served as living quarters, canteens and drying areas for sinkers, the itinerant workforce that would dig new vertical mine shafts.[63]

Representing other traditional past-times, the village fields include a quoits pitch, with another refreshment hut alongside it, resembling a wooden clubhouse.

In one of the fields in the village stands the Cupola, a small round flat topped brick built tower; such structures were commonly placed on top of disused or ventilation shafts, also used as an emergency exit from the upper seams.[59]

The Georgian North (1825)

[edit]A late Georgian landscape based around the original Pockerley farm represents the period of change in the region as transport links were improved and as agriculture changed as machinery and field management developed, and breeding stock was improved.[64] It became part of the museum in 1990, having latterly been occupied by a tenant farmer, and was opened as an exhibit in 1995. The hill top position suggests the site was the location of an Iron Age fort - the first recorded mention of a dwelling is in the 1183 Buke of Boldon (the region's equivalent of the Domesday Book). The name Pockerley has Saxon origins - "Pock" or "Pokor" meaning "pimple of bag-like" hill, and "Ley" meaning woodland clearing.[23]

The surrounding farmlands have been returned to a post-enclosure landscape with ridge and furrow topography, divided into smaller fields by traditional riven oak fencing. The land is worked and grazed by traditional methods and breeds.[64]

Pockerley Old Hall

[edit]

The estate of Pockerley Old Hall is presented as that of a well off tenant farmer, in a position to take advantage of the agricultural advances of the era. The hall itself consists of the Old House, which is adjoined (but not connected to) the New House, both south facing two storey sandstone built buildings, the Old House also having a small north–south aligned extension. Roof timbers in the sandstone built Old House have been dated to the 1440s, but the lower storey (the undercroft) may be from even earlier. The New House dates to the late 1700s, and replaced a medieval manor house to the east of the Old House as the main farm house - once replaced itself, the Old House is believed to have been let to the farm manager. Visitors can access all rooms in the New and Old House, except the north–south extension which is now a toilet block. Displays include traditional cooking, such as the drying of oatcakes over a wooden rack (flake) over the fireplace in the Old House.[65]

Inside the New House the downstairs consists of a main kitchen and a secondary kitchen (scullery) with pantry. It also includes a living room, although as the main room of the house, most meals would have been eaten in the main kitchen, equipped with an early range, boiler and hot air oven. Upstairs is a main bedroom and a second bedroom for children; to the rear (i.e. the colder, north side), are bedrooms for a servant and the servant lad respectively. Above the kitchen (for transferred warmth) is a grain and fleece store, with attached bacon loft, a narrow space behind the wall where bacon or hams, usually salted first, would be hung to be smoked by the kitchen fire (entering through a small door in the chimney).[65]

Presented as having sparse and more old fashioned furnishings, the Old House is presented as being occupied in the upper story only, consisting of a main room used as the kitchen, bedroom and for washing, with the only other rooms being an adjoining second bedroom and an overhanging toilet. The main bed is an oak box bed dating to 1712, obtained from Star House in Baldersdale in 1962. Originally a defensive house in its own right, the lower level of the Old House is an undercroft, or vaulted basement chamber, with 1.5 metre thick walls - in times of attack the original tenant family would have retreated here with their valuables, although in its later use as the farm managers house, it is now presented as a storage and work room, housing a large wooden cheese press.[65] More children would have slept in the attic of the Old House (not accessible as a display).

To the front of the hall is a terraced garden featuring an ornamental garden with herbs and flowers, a vegetable garden, and an orchard, all laid out and planted according to the designs of William Falla of Gateshead, who had the largest nursery in Britain from 1804 to 1830.[66]

The buildings to the east of the hall, across a north–south track, are the original farmstead buildings dating from around 1800. These include stables and a cart shed arranged around a fold yard. The horses and carts on display are typical of North Eastern farms of the era, Fells or Dales ponies and Cleveland Bay horses, and two wheeled long carts for hilly terrain (as opposed to four wheel carts).[67]

Pockerley Waggonway

[edit]

The Pockerley Waggonway opened in 2001, and represents the year 1825, as the year the Stockton and Darlington Railway opened. Waggonways had appeared around 1600, and by the 1800s were common in mining areas - prior to 1800 they had been either horse or gravity powered, before the invention of steam engines (initially used as static winding engines), and later mobile steam locomotives.[24]

Housing the locomotives and rolling stock is the Great Shed, which opened in 2001 and is based on Timothy Hackworth's erecting shop, Shildon railway works, and incorporating some material from Robert Stephenson and Company's Newcastle works. Visitors can walk around the locomotives in the shed, and when in steam, can take rides to the end of the track and back in the line's assorted rolling stock - situated next to the Great Shed is a single platform for passenger use. In the corner of the main shed is a corner office, presented as a locomotive designer's office (only visible to visitors through windows). Off the pedestrian entrance in the southern side is a room presented as the engine crew's break room. Atop the Great Shed is a weather vane depicting a waggonway train approaching a cow, a reference to a famous quote by George Stephenson when asked by parliament in 1825 what would happen in such an eventuality - "very awkward indeed - for the coo!".[24]

At the far end of the waggonway is the (fictional) coal mine Pockerley Gin Pit, which the waggonway notionally exists to serve. The pit head features a horse powered wooden whim gin, which was the method used before steam engines for hauling men and material up and down mineshafts - coal was carried in corves (wicker baskets), while miners held onto the rope with their foot in an attached loop.[68]

Wooden waggonway

[edit]Following creation of the Pockerley Waggonway, the museum went back a chapter in railway history to create a horse-worked wooden waggonway.

St Helen's Church

[edit]

St Helen's Church represents a typical type of country church found in North Yorkshire, and was relocated from its original site in Eston, North Yorkshire.[31] It is the oldest and most complex building moved to the museum.[69] It opened in November 2015, but will not be consecrated as this would place restrictions on what could be done with the building under church law.[31]

The church had existed on its original site since around 1100.[69] As the congregation grew, it was replaced by two nearby churches, and latterly became a cemetery chapel.[31] After closing in 1985, it fell into disrepair and by 1996 was burnt out and vandalised[31] leading to the decision by the local authority in 1998 to demolish it.[69] Working to a deadline of a threatened demolition within six months, the building was deconstructed and moved to Beamish, reconstruction being authorised in 2011, with the exterior build completed by 2012.[31]

While the structure was found to contain some stones from the 1100 era,[31] the building itself however dates from three distinct building phases - the chancel on the east end dates from around 1450, while the nave, which was built at the same time, was modernised in 1822 in the Churchwarden style, adding a vestry. The bell tower dates from the late 1600s - one of the two bells is a rare dated Tudor example.[69] Gargoyles, originally hidden in the walls and believed to have been pranks by the original builders, have been made visible in the reconstruction.[31]

Restored to its 1822 condition, the interior has been furnished with Georgian box pews sourced from a church in Somerset.[31] Visitors can access all parts except the bell tower. The nave includes a small gallery level, at the tower end, while the chancel includes a church office.

A Hearse House (shed for a horse-drawn hearse) has been reconstructed near the church.

Joe the Quilter's Cottage

[edit]The most recent addition to the area opened to the public in 2018 is a recreation of a heather-thatched cottage which features stones from the Georgian quilter Joseph Hedley's original home in Northumberland. It was uncovered during an archaeological dig by Beamish. His original cottage was demolished in 1872 and has been carefully recreated with the help of a drawing on a postcard. The exhibit tells the story of quilting and the growth of cottage industries in the early 1800s. Within there is often a volunteer or member of staff not only telling the story of how Joe was murdered in 1826, a crime that remains unsolved to this day, but also giving visitors the opportunity to learn more and even have a go at quilting.[70]

Other

[edit]A pack pony track passes through the scene - pack horses having been the mode of transport for all manner of heavy goods where no waggonway exists, being also able to reach places where carriages and wagons could not access. Beside the waggonway is a gibbet.

Farm (1940s)

[edit]Presented as Home Farm, this represents the role of North East farms as part of the British Home Front during World War II, depicting life indoors, and outside on the land. Much of the farmstead is original, and opened as a museum display in 1983. The farm is laid out across a north–south public road; to the west is the farmhouse and most of the farm buildings, while on the east side are a pair of cottages, the British Kitchen, an outdoor toilet ("netty"), a bull field, duck pond and large shed.[17]

The farm complex was rebuilt in the mid-19th century as a model farm incorporating a horse mill and a steam-powered threshing mill. It was not presented as a 1940s farm until early 2014.

The farmhouse is presented as having been modernised, following the installation of electric power and an Aga cooker in the scullery, although the main kitchen still has the typical coal-fired black range. Lino flooring allowed quicker cleaning times, while a radio set allowed the family to keep up to date with wartime news. An office next to the kitchen would have served both as the administration centre for the wartime farm, and as a local Home Guard office. Outside the farmhouse is an improvised Home Guard pillbox fashioned from half an egg-ended steam boiler, relocated from its original position near Durham.[17]

The farm is equipped with three tractors which would have all seen service during the war: a Case, a Fordson N and a 1924 Fordson F. The farm also features horse-drawn traps, reflecting the effect wartime rationing of petrol would have had on car use. The farming equipment in the cart and machinery sheds reflects the transition of the time from horse-drawn to tractor-pulled implements, with some older equipment put back into use due to the war, as well as a large Foster thresher, vital for cereal crops, and built specifically for the war effort, sold at the Newcastle Show. Although the wartime focus was on crops, the farm also features breeds of sheep, cattle, pigs and poultry that would have been typical for the time. The farm also has a portable steam engine, not in use, but presented as having been left out for collection as part of a wartime scrap metal drive.[17]

The cottages would have housed farm labourers, but are presented as having new uses for the war: Orchard Cottage housing a family of evacuees, and Garden Cottage serving as a billet for members of the Women's Land Army (Land Girls). Orchard Cottage is named for an orchard next to it, which also contains an Anderson shelter, reconstructed from partial pieces of ones recovered from around the region. Orchard Cottage, which has both front and back kitchens, is presented as having an up to date blue enameled kitchen range, with hot water supplied from a coke stove, as well as a modern accessible bathroom. Orchard Cottage is also used to stage recreations of wartime activities for schools, elderly groups and those living with dementia. Garden Cottage is sparsely furnished with a mix of items, reflecting the few possessions Land Girls were able to take with them, although unusually the cottage is depicted with a bathroom, and electricity (due to proximity to a colliery).[17]

The British Kitchen is both a display and one of the museum's catering facilities; it represents an installation of one of the wartime British Restaurants, complete with propaganda posters and a suitably patriotic menu.[17]

Town (1950s)

[edit]

As part of the Remaking Beamish project,[71] with significant funding from the National Lottery Heritage Fund, the museum is creating a 1950s town. Opened in July 2019, the Welfare Hall is an exact replica of the Leasingthorne Colliery Welfare Hall and Community Centre which was built in 1957 near Bishop Auckland.[72] Visitors can 'take part in activities including dancing, crafts, Meccano, beetle drive, keep fit and amateur dramatics' while also taking a look at the National Health Service exhibition on display, recreating the environment of an NHS clinic.[70] A recreation and play park, named Coronation Park was opened in May 2022 to coincide with the celebrations around the Platinum Jubilee of Elizabeth II.[73][74]

The museum's first 1950s terrace opened in February 2022.[75] This included a fish and chip shop from Middleton St George, a cafe, a replica of Norman Cornish's home, and a hairdressers. Future developments opposite the existing 1950s terrace will see a recreation of The Grand Cinema, from Ryhope, in Sunderland, and toy and electricians shops. Also underdevelopment are a 1950s bowling green and pavilion, police houses and aged miner's cottages. Also under construction are semi-detached houses; for this exhibit, a competition was held to recreate a particular home at Beamish, which was won by a family from Sunderland.[76]

As well as the town, a 1950s Northern bus depot has been opened on the western side of the museum – the purpose of this is to provide additional capacity for bus, trolleybus and tram storage once the planned trolleybus extension and the new area are completed, providing extra capacity and meeting the need for modified routing.[70]

Spain's Field Farm

[edit]In March 2022, the museum opened Spain's Field Farm. It had stood for centuries at Eastgate in Weardale, and was moved to Beamish stone-by-stone. It is exhibited as it would have been in the 1950s.[77]

1820s Expansion

[edit]In the area surrounding the current Pockerley Old Hall and Steam Wagon Way more development is on the way. The first of these was planned to be a Georgian Coaching Inn that would be the museum's first venture into overnight accommodation.[78] However following the COVID-19 pandemic this was abandoned, in favour of self-catering accommodation in existing cottages.[79]

There are also plans for 1820s industries including a blacksmith's forge and a pottery.[80][81]

Museum stores

[edit]There are two stores on the museum site, used to house donated objects. In contrast to the traditional rotation practice used in museums where items are exchanged regularly between store and display, it is Beamish policy that most of their exhibits are to be in use and on display - those items that must be stored are to be used in the museum's future developments.[82]

Open Store

[edit]Housed in the Regional Resource Centre, the Open Store is accessible to visitors.[82] Objects are housed on racks along one wall, while the bulk of items are in a rolling archive, with one set of shelves opened, with perspex across their fronts to permit viewing without touching.

Regional Museums Store

[edit]The real purposes of the building presented as Beamish Waggon and Iron Works next to Rowley Station is as the Regional Museums Store, completed in 2002, which Beamish shares with Tyne and Wear Museums. This houses, amongst other things, a large marine diesel engine by William Doxford & Sons of Pallion, Sunderland (1977); and several boats including the Tyne wherry (a traditional local type of lighter) Elswick No. 2 (1930).[83] The store is only open at selected times, and for special tours which can be arranged through the museum; however, a number of viewing windows have been provided for use at other times.

Transport collection

[edit]The museum contains much of transport interest, and the size of its site makes good internal transportation for visitors and staff purposes a necessity.[84][85]

The collection contains a variety of historical vehicles for road, rail and tramways. In addition there are some modern working replicas to enhance the various scenes in the museum.

Agriculture

[edit]The museum's two farms help to preserve traditional northcountry and in some cases rare livestock breeds such as Durham Shorthorn Cattle;[86] Clydesdale and Cleveland Bay working horses; Dales ponies; Teeswater sheep; Saddleback pigs; and poultry.

Regional heritage

[edit]Other large exhibits collected by the museum include a tracked steam shovel, and a coal drop from Seaham Harbour.[87]

In 2001 a new-build Regional Resource Centre (accessible to visitors by appointment) opened on the site to provide accommodation for the museum's core collections of smaller items. These include over 300,000 historic photographs, printed books and ephemera, and oral history recordings. The object collections cover the museum's specialities. These include quilts;[88] "clippy mats" (rag rugs);[89] Trade union banners;[90][91] floorcloth; advertising (including archives from United Biscuits and Rowntree's); locally made pottery; folk art; and occupational costume. Much of the collection is viewable online[92] and the arts of quilting, rug making and cookery in the local traditions are demonstrated at the museum.

Filming location

[edit]The site has been used as the backdrop for many film and television productions, particularly Catherine Cookson dramas, produced by Tyne Tees Television, and the final episode and the feature film version of Downton Abbey.[93] Some of the children's television series Supergran was shot here.[94]

Visitor numbers

[edit]On its opening day the museum set a record by attracting a two-hour queue.[3] Visitor numbers rose rapidly to around 450,000 p.a. during the first decade of opening to the public,[95] with the millionth visitor arriving in 1978.[4]

Awards

[edit]| Award | Issuer | Year | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Museum of the Year | 1986 | [95] | |

| European Museum of the Year Award | 1987 | [95] | |

| Living Museum of the Year | 2002 | [95] | |

| Large Visitor Attraction of the Year | North East England Tourism awards | 2014 & 2015 | [32] |

| Large Visitor Attraction of the Year (bronze) | VisitEngland awards | 2016 | [32] |

It was designated by the Museums, Libraries and Archives Council in 1997 as a museum with outstanding collections.[citation needed]

Critical responses

[edit]In responding to criticism that it trades on nostalgia[96] the museum is unapologetic. A former director has written: "As individuals and communities we have a deep need and desire to understand ourselves in time."[97]

According to the BBC writing in its 40th anniversary year, Beamish was a mould-breaking museum that became a great success due to its collection policy, and what sets it apart from other museums is the use of costumed people to impart knowledge to visitors, rather than labels or interpretive panels (although some such panels do exist on the site), which means it "engages the visitor with history in a unique way".[95]

Legacy

[edit]Beamish was influential on the Black Country Living Museum, Blists Hill Victorian Town and, in the view of museologist Kenneth Hudson, more widely in the museum community[98] and is a significant educational resource locally. It can also demonstrate its benefit to the contemporary local economy.[99]

The unselective collecting policy has created a lasting bond between museum and community.[6][95]

Gallery

[edit]-

East end of the main street in Town

-

Beamish Museum.

-

Kitchen in the Beamish Museum

-

Bathroom in the Beamish Museum

See also

[edit]- Amberley Museum & Heritage Centre – Amberley, West Sussex

- Avoncroft Museum of Historic Buildings – Bromsgrove, England

- Black Country Living Museum – Dudley, England

- Blists Hill Victorian Town – Telford, England

- Cregneash – The National Folk Museum at Cregneash, Isle of Man

- Highland Folk Museum – Newtonmore, Scotland

- Milestones Museum – Basingstoke, England

- St Fagans National Museum of History – Museum of Welsh Life, Cardiff, Wales

- Summerlee Museum of Scottish Industrial Life – Coatbridge, Scotland

- Ulster Folk and Transport Museums – Cultra, Northern Ireland

Further reading

[edit]- Joyce, J; King, J S; Newman, A G (1986). British Trolleybus Systems. Ian Allan. ISBN 978-0-7110-1647-7.

- De Nardi, Sarah (11 November 2019). "Stories from Beamish Museum's '1950s town'". Visualising Place, Memory and the Imagined. pp. 122–147. doi:10.4324/9781315167879-7. ISBN 9781315167879. S2CID 213602300.

- Ludwig, Carol; Wang, Yi-Wen (31 December 2020). "5 Contemporary Fabrication of Pasts and the Creation of New Identities?: Open-Air Museums and Historical Theme Parks in the UK and China". The Heritage Turn in China: 131–168. doi:10.1515/9789048536818-007. ISBN 9789048536818. S2CID 242415064.

References

[edit]- ^ "Beamish official website". Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ a b c Atkinson, Frank (1999). The Man Who Made Beamish: an autobiography. Gateshead: Northern Books. ISBN 978-0-9535730-0-4.

- ^ a b c d e Wainwright, Martin (2 January 2015). "Frank Atkinson obituary". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Essential Guide 2014, pp. 116–119.

- ^ Atkinson, Frank (1985). "The unselective collector". Museums Journal. 85: 9–11.

- ^ a b c d e f g Allan, Rosemary E. (2003). Beamish, the North of England Open Air Museum: the experience of a lifetime. Jarrold. ISBN 978-0-7117-2996-4.

- ^ a b Allan, Rosemary E. (1991). Beamish, the North of England Open Air Museum: the making of a museum. Beamish. ISBN 978-0-905054-07-0.

- ^ a b c Essential Guide 2014, p. 117.

- ^ a b "Rowley railway station". subbrit.org.uk. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Essential Guide 2014, pp. 38–39.

- ^ a b c Essential Guide 2014, pp. 18–21.

- ^ a b c Essential Guide 2014, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Atkinson, Frank (1985). "The Town and how it began". Friends of Beamish Museum Magazine. 3: 2–7.

- ^ a b Essential Guide 2014, pp. 60–61.

- ^ a b c Essential Guide 2014, pp. 54–59.

- ^ a b c d Essential Guide 2014, pp. 46–47.

- ^ a b c d e f Essential Guide 2014, pp. 6–15.

- ^ a b c Lewis, Peter (1991). "Dependence or independence". In Ambrose, Timothy (ed.). Money, Money, Money & Museums. Edinburgh: H.M.S.O. pp. 38–49. ISBN 978-0-11-494110-9.

- ^ a b Essential Guide 2014, pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b Essential Guide 2014, pp. 24–25.

- ^ a b Essential Guide 2014, pp. 48–49.

- ^ a b Essential Guide 2014, pp. 70–71.

- ^ a b Essential Guide 2014, pp. 86–87.

- ^ a b c Essential Guide 2014, pp. 82–85.

- ^ a b Essential Guide 2014, pp. 72–73.

- ^ a b Essential Guide 2014, p. 37.

- ^ a b Essential Guide 2014, pp. 28–29.

- ^ a b Essential Guide 2014, pp. 30–31.

- ^ a b Essential Guide 2014, pp. 32–33.

- ^ a b c Essential Guide 2014, p. 74.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Whetstone, David (13 November 2015). "Beamish Museum gives new lease of life to little church that was scheduled for demolition". Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Gouk, Anne (6 April 2016). "Beamish Museum's £17m expansion plan approved by Durham". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- ^ "Gateshead WWII houses resurrected at Beamish Museum". BBC News. 9 May 2012. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ^ a b Essential Guide 2014, p. 4.

- ^ Essential Guide 2014, p. 127.

- ^ "Friends of Beamish Museum". Archived from the original on 22 December 2007. Retrieved 13 January 2008.

- ^ Atkinson, Frank (1985). "The Town and how it began". Friends of Beamish Museum Magazine. 3: 2–7.

- ^ a b Essential Guide 2014, p. 96.

- ^ "Beamish Museum Tramway". Archived from the original on 1 January 2008. Retrieved 13 January 2008.

- ^ Lewis, Peter (1997). "A transport of delight: the tram operation at Beamish, the North of England Open Air Museum". Friends of Beamish Newsletter. 109: 17–24.

- ^ Thomas, Doreen (1971). "Hardcastle's". Cleveland & Teesside Local History Society Bulletin. 14: 27–30.

- ^ Buxton, Andrew (2004). Cash Carriers in Shops. Princes Risborough: Shire Publications. ISBN 978-0-7478-0615-8.

- ^ "The Cash Railway website". Archived from the original on 17 January 2008. Retrieved 13 January 2008.

- ^ Gilmour, Alastair (1 March 2015). "The Sun Inn, Durham, pub review" – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ Gilmour, Alastair (13 June 2009). "The Sun Inn, Beamish Museum, County Durham". The Guardian – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ Essential Guide 2014, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Echoes of the past for north museum. Sunderland Echo. 8 May 1991. p. 7.

- ^ a b Whetstone, David (7 May 2016). "Has Beamish kickstarted the high street revival with the opening of two new shops?". Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ^ "W. Smith's amazing aerated waters!". Beamish Buildings. 29 October 2014. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ^ Essential Guide 2014, p. 75.

- ^ pp. 6-7, Beamish North of England Open Air Museum, 1984, Beamish Museum

- ^ a b c d e f g Essential Guide 2014, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Essential Guide 2014, p. 35.

- ^ Essential Guide 2014, p. 40.

- ^ a b Essential Guide 2014, p. 36.

- ^ a b c Essential Guide 2014, pp. 42–43.

- ^ "Colliery Engine Moves..." 6 November 2014. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ Atkinson, Frank (1978). "The Beamish symbol: a "chaldron" wagon". Beamish: Report of the North of England Open Air Museum Joint Committee. 1: 32–9.

- ^ a b Essential Guide 2014, p. 41.

- ^ Essential Guide 2014, p. 16.

- ^ Essential Guide 2014, p. 22.

- ^ Langley, Leigh (1992). Our Chapel. Beamish. ISBN 978-0-905054-08-7.

- ^ Essential Guide 2014, p. 23.

- ^ a b Essential Guide 2014, p. 80.

- ^ a b c Essential Guide 2014, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Essential Guide 2014, p. 92.

- ^ Essential Guide 2014, p. 93.

- ^ Essential Guide 2014, p. 81.

- ^ a b c d Essential Guide 2014, pp. 94–95.

- ^ a b c "Remaking Beamish - Find out about the museum's expansion plans". Beamish. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- ^ "Job Vacancy: Remaking Beamish Administration Assistant".

- ^ "Welfare Hall". Beamish. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- ^ "1950s Coronation Park and Recreation Ground opens at Beamish Museum!".

- ^ "First look as iconic playground from the 1950s finally opens at Beamish Museum".

- ^ "Beamish opens brand new 1950s Front Street terrace with week-long celebrations taking place". Evening Chronicle. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ "Sunderland family to have their home rebuilt at Beamish". April 2015.

- ^ "Sneak peek at Beamish Museum's new 1950s Spain's Field farm ahead of opening to the public". Sunderland Echo. 14 March 2022.

- ^ "Georgian Inn". Beamish. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- ^ "Pockerley Farm Cottages and Flint Mill Cottages". Beamish. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ "Blacksmith's". Beamish. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ "Georgian Pottery". Beamish. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ a b Essential Guide 2014, p. 103.

- ^ The Regional Museums Store for North East England: catalogue of collections (CD-ROM). Beamish: Regional Museums Store.

- ^ Atkinson, Frank (1980). "Beamish North of England Open Air Museum". Yesteryear Transport. 3: 76–9.

- ^ Barnes, Alan (November 2012). "Beamish's Commercial enterprise". Vintage Spirit (124): 36–9.

- ^ Atkinson, Frank (1986). "Life in the old breed yet: saving the Durham Shorthorn". Country Life. 179: 827, 830.

- ^ Atkinson, Frank (1975). "Preservation of Seaham Harbour coal drop and the history of coal transport in the North East". Transactions of the First International Congress on the Preservation of Industrial Monuments. pp. 155–7.

- ^ Allan, Rosemary E. (2007). Quilts & Coverlets: the Beamish collections. Beamish. ISBN 978-0-905054-11-7.

- ^ Allan, Rosemary E. (2007). From Rags to Riches: North Country Rag Rugs. The Beamish Collections. Beamish. ISBN 978-0-905054-12-4.

- ^ Moyes, William A. (1974). The Banner Book: a study of the banners of the lodges of Durham Miners' Association. Newcastle: Frank Graham. ISBN 978-0-85983-085-0.

- ^ Clark, Robert (1985). "Banners for Beamish". Friends of Beamish Museum Magazine. 3: 10–14.

- ^ "Beamish Collections Online". Retrieved 13 January 2008.

- ^ Brown, Michael (15 July 2015). "Downton Abbey brings snow to the streets of Beamish Museum - in July". Evening Chronicle. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ^ "Supergran - Hollywood on Tyne". BBC Home. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f "Beamish Museum in County Durham has turned 40". BBC News. 2 July 2010. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- ^ Bennett, Tony (1988). "Museums and "the people"". In Lumley, Robert (ed.). The Museum Time-Machine: putting cultures on display. London: Routledge. pp. 63–85. ISBN 978-0-415-00651-4.

- ^ Lewis, Peter (1988). "History, heritage or nostalgia?". Friends of Beamish Museum Magazine. 6: 28–31.

- ^ Hudson, Kenneth (1987). Museums of Influence. Cambridge University Press. pp. 126–31. ISBN 978-0-521-30534-1.

- ^ Johnson, Peter; Thomas, Barry (1992). Tourism, Museums and the Local Economy: the economic impact of the North of England Open Air Museum at Beamish. Aldershot: Elgar. ISBN 978-1-85278-617-5.

- Beamish Museum (2014). The Essential Guide to Beamish. Norwich, England: Jarrold Publishing. ISBN 9780851015385.

Spiral-bound

External links

[edit]- 1970 establishments in England

- Agricultural museums in England

- Industry museums in England

- Living museums in England

- Museums established in 1970

- Museums in County Durham

- Heritage railways in County Durham

- Open-air museums in England

- Preserved stationary steam engines

- Railway museums in England

- Tram museums in the United Kingdom

- Tram transport in England

- Tramways with double-decker trams

- Transport museums in England

- Industrial archaeological sites in England