Bayshore Cutoff

| Bayshore Cutoff | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other name(s) | Bay Shore Cut-Off | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Revenue service | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | Peninsula Corridor Joint Powers Board | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

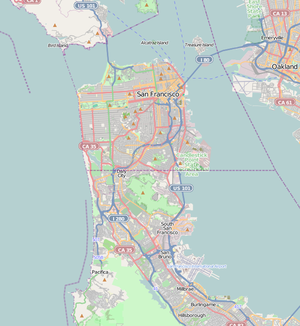

| Locale | San Francisco and northern San Mateo counties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Termini | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stations | 7 (2 closed) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Service | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Type | Commuter rail, heavy rail | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| System | SP (Coast Line, Peninsula Commute; 1863–1992) Caltrain and Union Pacific (1992–present) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Commenced | October 26, 1904 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Completed | December 8, 1907 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line length | 11.04 mi (17.77 km) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Number of tracks | 2 (4 in Brisbane after CTX) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrification | Overhead line, 25 kV 60 Hz AC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operating speed | 79 mph (127 km/h) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Highest elevation | 20.3 ft (6.2 m) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

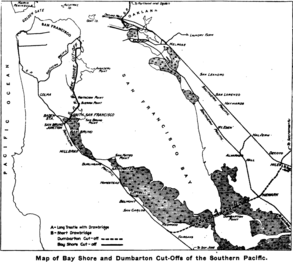

The Bayshore Cutoff (originally the Southern Pacific Bay Shore Cut-Off)[1] is the rail line between San Francisco and San Bruno along the eastern shore (San Francisco Bay side) of the San Francisco Peninsula. It was completed by Southern Pacific (SP) in 1907 at a cost of $7 million (equivalent to $229 million adjusted for inflation), and included five tunnels, four of which are still used by Caltrain, the successor to Southern Pacific's Peninsula Commute service. Fill from the five tunnels was used to build the Visitacion or Bayshore Yard, the main SP classification yard near the city of Brisbane. The Del Monte was similarly rerouted over the line at some point in its operational history.

The original alignment of the Coast Line completed in 1863 took it around the western side of San Bruno Mountain, through Colma and Daly City. Rail traffic along the original route needed helper engines for grades and curves along a route nearly 13 miles (21 km) long. The Bayshore Cutoff reduced the distance to 10.5 miles (16.9 km) with a maximum grade of 0.3 percent.

Once the Bayshore Cutoff was completed, and main line traffic was shifted to it, the former route was renamed the Ocean View Branch line. It was used to carry coffins to Colma; it was severed in the 1940s, but a few miles at the south end was still in SP's 1996 timetable. In the late 1980s BART purchased the right-of-way of the Ocean View line for the San Francisco International Airport extension south from Daly City.

Bayshore Cutoff Tunnel 5, at Sierra Point, was abandoned when the easternmost tip of the point was leveled during construction of the Bayshore Freeway in 1955–56, and the line was rerouted through the leveled section as well. The rail yard was in operation until the 1970s, and the site is currently being considered for redevelopment for light industrial/retail use as part of the Brisbane Baylands development project.

History

[edit]

The original route between San Francisco and San Bruno was laid by the San Francisco and San Jose Railroad (SF&SJ), one of the companies that later was absorbed into the Southern Pacific (SP). From the station in San Francisco at Mariposa and 18th, tracks were laid generally bearing west-southwest through the Mission District close to the present-day route of San Jose Avenue.

Southern Pacific took over the Peninsula Corridor in 1870 from the SF&SJ and began operating the Peninsula Commute between San Francisco and San Jose. Surveys were conducted for an alternate route east of San Bruno Mountain as early as 1878[2] and in 1894, it was revealed that SP had secretly purchased a more direct route along the shoreline of San Francisco Bay through an agent, Alfred E. Davis, who had previously built a narrow-gauge railroad to Santa Cruz.[3] By 1900, the Bayshore Cutoff route, including five tunnels, had been designed and plans were announced to start work "within a few weeks".[2] The San Francisco Board of Supervisors attempted to compel SP to start using the Bayshore route by passing an ordinance in 1900 directing the Board of Public Works (BPW) to tear up the existing tracks. SP was granted an injunction to prevent that action, but BPW Commissioner Maguire planned to bring witnesses "to testify that the clanging of bells, shrieks of whistles, etc., interferes with the comfort and peace of the surrounding residents."[4]

SP announced firm plans to build the Bayshore Cutoff and double-track the line in late 1901.[5] President E. H. Harriman reiterated SP's plans to construct the Cutoff in mid-1902, predicting completion within the calendar year. Double-tracking from Burlingame south to San Jose was announced as well,[6] and completed by 1903.[7] In conjunction with the Dumbarton Cutoff, the Bayshore Cutoff was designed to facilitate transcontinental rail service into San Francisco.[8] Instead of being a remote spur terminal, San Francisco would become "practically the same as a main line station" with the completion of the two new cutoffs, and transcontinental freight could then be loaded directly on trains without having to be ferried across the Bay.[9]

The San Jose-based Evening News touted the benefits of the Cutoff, saying the fifteen minute savings in travel time combined with a more temperate climate would naturally lead to increased population in San Jose: "The warmer, drier and more even climatic conditions make [San Jose] far preferable for residence to a place where the men feel the need of an overcoat in the evening of the warmest days, and where the ladies scarcely know what it is to dress in light clothing and walk out in the evening."[10] In 1903, the route of the Bayshore Cutoff was adjusted slightly; the original route called for tracks along Islais and Tulare streets, which due to their narrow width, would have closed those streets to any other traffic. Over a one-year period, Joseph B. Coryell acted as agent for SP to purchase properties bordering Islais Creek to allow the rerouting of the line.[11]

The Bayshore Railway company was founded as a subsidiary of the Southern Pacific to build the Bayshore Cutoff.[12] Construction started in 1904[13] and was completed in 1907[14] at a cost of $7 million[15] (equivalent to $167 million in 2023[16]), one of the most expensive rail lines constructed to date.[12] In comparison, the Lucin Cutoff, which included a trestle across the northern end of the Great Salt Lake and saved 44 miles (71 km) of distance, cost $9 million. The Bayshore Cutoff, along with the Lucin and Montalvo Cutoffs, alleviated three key bottlenecks for Southern Pacific.[17]

Rail traffic to San Francisco shifted over to the new Bayshore Cutoff immediately and has remained on that route ever since. Caltrain now runs daily commuter trains through four of the tunnels built for the Bayshore Cutoff. The fifth tunnel at Sierra Point was bypassed with the completion of the Bayshore Freeway about 1956.

Southern Pacific Loop Service | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Legend

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The prior route west of San Bruno Mountain was renamed the Ocean View line and relegated to branch status. Although the Ocean View line was severed in 1942,[18][19] the rails remained in place until the right-of-way was sold to the Bay Area Rapid Transit District and construction began on the SFO BART extension.[20][21]: 3.13–42 Other potential routes proposed for the BART extension included an aerial structure along El Camino Real and a rail line parallel to I-280/380.[22]

SP also completed a rail yard at Visitacion near the city of Brisbane. SP had previously purchased Visitacion Cove and partially filled it using earth excavated from the tunnels as well as mud dredged from the Bay.[23][24] The yard was used to assemble trains and a large roundhouse and shops were used for steam locomotive maintenance. After diesel locomotives replaced steam by 1958 (the last steam locomotive in SP's system was a Peninsula Commute engine, which ran on January 22, 1957),[25] the yard was used less frequently. SP consolidated freight operations at Oakland in 1964, and the Bayshore Yard began to be dismantled in 1979.[25] The last day of work at the Bayshore shops was October 25, 1982;[26] the land was sold to Universal Paragon in 1989.[27]

Design

[edit]The line included five tunnels, numbered north to south, and a former railyard near Brisbane, the Visitacion or Bayshore Yard. The historic Bayshore Roundhouse, previously used to service SP's steam locomotives, still exists at the yard. The first four tunnels are within the city limits of San Francisco.[15]

The maximum grade of the completed Bayshore Cutoff is 15.8 feet per mile (2.99 m/km) (0.3% grade) compared to the 3% maximum grade of the older route.[15] The maximum elevation of the Bayshore Cutoff is 20.3 feet (6.2 m), while the prior route rose to 292 feet (89 m) above sea level. The total distance between San Francisco and San Bruno along the Cutoff is 11.04 miles (17.77 km), saving 2.65 miles (4.26 km) over the original route west of San Bruno Mountain.[15] The original 1900 design called for an aggregate length of the two tunnels under Potrero Hill and Sierra Point of 1,800 feet (550 m).[2]

After completion, travel time from San Jose to San Francisco was cut from two hours to ninety minutes (for local trains) and seventy minutes (for limited-stop trains). The Evening News breathlessly advertised "the annihilation of seventeen minutes in a schedule" in an article covering the opening of the Cutoff.[28]

Although the Bayshore Cutoff is double-tracked,[29] the right-of-way outside the tunnels is sized to accommodate quad tracks.[27] Quad tracks were added in Brisbane as part of the Caltrain Express project from 2004 to 2006.

Construction

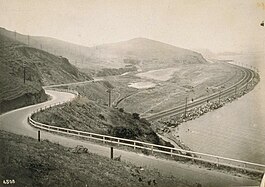

[edit]Initial bids on construction costs ranged between $2 and $2.5 million (between $67.8 million and $84.8 million in 2023 adjusted for inflation).[13] Preliminary work began in April 1904,[30] and actual construction started on October 26 of that year.[31] An earthquake in late November 1904 was at first mistaken for blasting being done for the Cutoff.[32] Work on the first tunnel (which was later designated Tunnel No. 5) at Sierra Point began on April 18, 1905, and at the time it was predicted that revenue service would begin on December 31, 1906.[33] A week and a half later, a steam shovel had excavated 150 feet (46 m) (starting from the south portal) and work had begun on the second tunnel (later designated Tunnel No. 4), which had reached a length of 200 feet (61 m).[34] After the Lucin Cutoff was completed, workers on that job moved to the Bayshore project, and orders were placed for forty iron arches, each spanning 30 ft (9.1 m), to be used in tunnel construction.[35]

By May 1905, good progress was being made, as workers excavating the tunnel had found "nothing harder than sand and earth", but they were forced to wear rubber clothes due to the damp conditions.[36] Two shifts of work were started in June, and the stone blocks to be used in the portals had arrived at Tunnel 5.[37] By July, work on the final tunnel (later designated Tunnel No. 3) had started, and SP General Manager E.E. Calvin confidently predicted all tunnels would be completed in 1906.[29] Heavy rain during February 1906 damaged the roadbed between South San Francisco and San Bruno when the final stages of construction were about to commence.[38]

Work was being performed in two shifts when the 1906 San Francisco earthquake struck in April. Workers in Tunnel 3 (below the orphanage) were terrified by the shaking, which extinguished the lamps they were using, but no one was injured and the tunnel was not damaged.[39] After the earthquake, construction continued. Earthquake survivors were unnerved by blasting for the tunnels, which they thought were aftershocks.[14] Some of the areas for the Bayshore Cutoff route south of China Basin were filled with rubble from the earthquake, allowing more rapid progress than planned.[40] SP officials announced in August 1906 the estimated completion date for the Bayshore Cutoff would be January 24, 1907. Once the Cutoff was in place, they stated that more frequent service would be offered for commuters, with headways of 30 minutes and total travel time to San Jose estimated at one hour.[41]

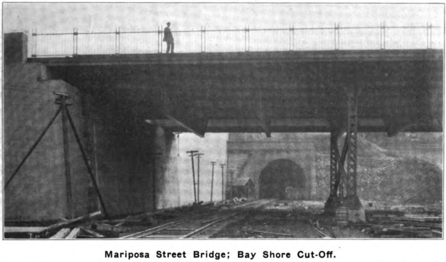

By July 1907, four bridges still needed to be completed for the Cutoff, touted to be "one of the fastest pieces of railroad in the United States" once it was completed.[42] The steel girders were delayed in transit and the completion date of the Cutoff was delayed from October to November 1907.[43] A final carload of steel was rushed from Ogden to complete the Fifth Avenue crossing, and the first planned passenger trains to use the Cutoff would be for fans from San Francisco traveling to Stanford to watch a football game.[44] The new line officially opened on December 8, 1907.[28]

-

Five-drift tunnel construction (Tunnel No. 3)

-

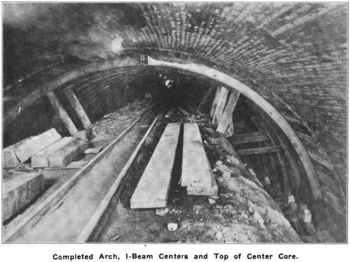

Brick arch in tunnel

-

Nearly complete tunnel, with steel arch forms

-

Steam shovel working in cut (1906)

-

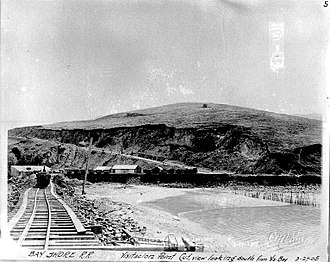

Cut at Visitacion Point (1905)

-

North from Sierra Point, prior to fill (1905)

-

Bridge at Mariposa Street (1907)

-

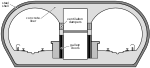

Tunnel and portal details (1904)

-

Map of Bayshore and Dumbarton Cut-Offs

Tunnels

[edit]Average progress on the tunnels was 8 feet per day (2.4 m/d).[15] The aggregate length of the five tunnels is 9,947 feet (3,032 m) as completed[15] (10,180 feet (3,100 m) as designed),[45] which is one-fifth of the entire 9.81-mile (15.79 km) length of the Bayshore Cutoff.[27] Each tunnel shares the same cross-section design, being a semicircular arch 30 feet (9.1 m) wide to accommodate two tracks spaced 13 feet (4.0 m) apart (centerline to centerline). Overall height in the center of the tunnel is 27 feet (8.2 m), with clearance of 22 feet (6.7 m) above the top of the rail at each track centerline. The tracks are elevated 1 foot 8 inches (0.51 m) above the tunnel floor by ballast and ties.[45]

Tunnel 2 was built using cut-and-cover, but the other four were built by first sinking pilot drifts approximately 8 by 7 feet (2.4 by 2.1 m) in cross-section at the bottom corners of the tunnel.[1][46] After these first two drifts were completed, the concrete side walls were partially built and timber supports were placed to allow the excavation of two more drifts on top of the first drifts up to the springing line where the semicircular brick arch meets the concrete side walls. With the side drift excavation complete, the concrete side walls are poured.[46] A fifth drift was then bored at the apex of the tunnel, followed by excavation of the remaining space between the apex and side drifts.[1] Once these initial excavations were complete, leaving a "core" of rock in the center of the tunnel, timber bracing was placed to support the rock at the top of the tunnel and a steel arch form was installed.[46] After covering the arch form with planks, five to six layers of brick were laid to form the semicircular arch, resting on concrete side walls.[1] The space between the top of the arch and the excavated tunnel was backfilled with loose rock, or concrete if the pressure was especially large. The temporary timber supports and arch form were removed, and the remainder of the tunnel was cleared by blasting, with the blasted rock being sorted for incorporation in the concrete.[46]

| No. | Length | Crosses | North portal | South Portal | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,817.3 ft 553.9 m[1] |

Potrero Hill | Mariposa St, between Pennsylvania & Indiana 37°45′50″N 122°23′34″W / 37.763992°N 122.392858°W |

22nd St (Pennsylvania & Iowa) 37°45′28″N 122°23′32″W / 37.757733°N 122.392337°W |

South portal (2010) |

| 2 | 1,086.4 ft 331.1 m[1] |

Potrero Hill | 23rd St (Pennsylvania & Indiana) 37°45′17″N 122°23′33″W / 37.754767°N 122.392490°W |

25th St (Connecticut & Pennsylvania) 37°45′06″N 122°23′35″W / 37.751800°N 122.392921°W |

North portal (2017) |

| 3 | 2,364 ft 721 m[1] |

Hunters Point | Palou Ave (Dunshee & Phelps) 37°44′12″N 122°23′42″W / 37.736763°N 122.395005°W |

Williams Ave (Diana & Reddy) 37°43′49″N 122°23′45″W / 37.730238°N 122.395885°W |

South portal (c. 1907) |

| 4 | 3,547 ft 1,081 m[1] |

Candlestick Point | Salinas Ave (Gould & Carr) 37°43′16″N 122°23′52″W / 37.721194°N 122.397869°W |

Blanken Ave (Bayshore & Tunnel) 37°42′43″N 122°24′04″W / 37.711814°N 122.401226°W |

South portal (2012) |

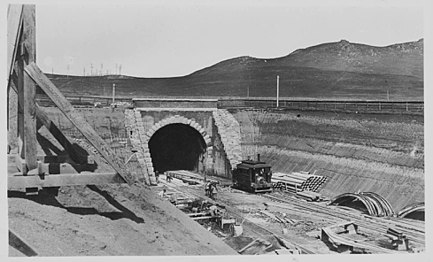

| 5 | 1,133.8 ft 345.6 m[1] |

Sierra Point | between Van Waters & Rogers Rd and Bayshore Blvd 37°40′34″N 122°23′27″W / 37.675999°N 122.390933°W |

between Bayshore Blvd & US 101 (now filled) 37°40′22″N 122°23′28″W / 37.672867°N 122.391118°W |

North portal (1908) |

Tunnels 1 and 2 bracket the present-day 22nd Street station. Tunnel 1 is just north of the station, and Tunnel 2 is south. Both tunnels are cut through Potrero Hill. Tunnel 2 is the only one of the five tunnels built with twin bores to accommodate four tracks, although the western bore is currently closed. The western bore was built because a high concrete retaining wall was needed to support a city street running alongside that second tunnel.[1] Tunnel Top Park, at 1100 Pennsylvania Avenue, is within the Caltrain-owned right-of-way. These two tunnels were bored through mostly serpentinite rock with clay seams.[1]

The Western Pacific Railroad (WP) also built a tunnel through Potrero Hill at nearly the same time;[47] support timbers within the Western Pacific tunnel caught fire in 1962, leading to its collapse and subsequent fill. The area on top of the WP tunnel remained undeveloped until the 1990s.[48]

Tunnel 3 traverses the Hunters Point neighborhood. It was built under the St. Joseph's orphan asylum. The tracks are 175 feet (53 m) below the ground's surface.[15] Tunnel 3 is bored through wet sand and hard silicated formations.[1]

Tunnel 4 crosses Candlestick Point. The former Schlage factory and headquarters, constructed in 1926, are located just west of the southern portal of Tunnel 4. In 1907, it was noted that Tunnel 4 had been bored through very wet ground and partly through shale.[1] The earthquake of April 1906 caused a spring to start leaking into Tunnel 4, which went unnoticed until several months after the seismic event, when the reinforced concrete of the completed tunnel began to bulge, eventually causing water to leak into the tunnel. The spring was not capped until 1911.[49]

Tunnel 5 crosses Sierra Point and was bored through hard sandstone.[1] Tunnel 5 was abandoned in 1956 when the old Bayshore Highway (which is now the present-day Bayshore Boulevard in Brisbane and South San Francisco) was expanded into the six-lane divided Bayshore Freeway.[50] The route for the freeway was moved to the east along a new causeway constructed on fill between Candlestick Point and Sierra Point,[51] which also pushed the rail line east, eliminating the need for the tunnel.[52] Some of the fill was taken by razing Sierra Point to the level of the railroad.[53] The southern portal would have emerged between Bayshore Boulevard and the Bayshore Freeway, but it has since been filled in. The northern portal still exists, but access is restricted by a padlocked fence next to a parking lot just off Bayshore Boulevard.

Bayshore Yard

[edit]- Cutoff

- Railyard

- Roundhouse

Fill taken from tunnel excavation and cuts was used to build a new railyard at Visitacion. One of the cuts, at Visitacion Point, was 95 feet (29 m) deep and removed 750,000 cubic yards (570,000 m3) of material.[27] SP purchased Visitacon Cove and constructed 2.5 miles (4.0 km) of trestles to dump fill into San Francisco Bay, reclaiming 156 acres (63 ha) of land in total.[15] In total, more than 3,000,000 cubic yards (2,300,000 m3) of fill were used to reclaim land for the railyard, including 1,895,000 cubic yards (1,449,000 m3) of mud dredged from San Francisco Bay. Because the Bayshore Yard was built on reclaimed land, building foundations were built on piles set, on average, 55 feet (17 m) deep, and the fill under the rails required constant replenishment for ten years until it was sufficiently compacted.[7]

The Bayshore Yard contained approximately 50–65 miles (80–105 km) of track, in an approximately triangular area bounded by the Bayshore Cutoff main line (on the east), the Bayshore Highway (on the west, now Bayshore Boulevard), Tunnel 4 (on the north), and the deep cut at Visitacion Point (on the south).[7] It extended 8,400 feet (2,600 m) in length, measured north to south, and 1,800 feet (550 m) wide east to west at the apex of the triangle.[23][24] An additional 18.2 miles (29.3 km) of track were authorized in January 1917 along with the main shop buildings. By 1921, the Bayshore Yard was substantially complete.[7]

The design of the Bayshore Yard had thirty-eight tracks in the main freight space; seven tracks on both the north and south ends each had a capacity of fifty cars. The north end of the yard also had fourteen storage tracks (total capacity of 472 cars) and eighteen classification tracks.[23] In all, the total capacity of the railyard was 1,068 cars on 24 inbound tracks, and 1,078 cars on 19 outbound tracks. 7 of the outbound tracks had a maximum capacity of 74 cars each. Most of the tracks were spaced at 13 feet (4.0 m) between centerlines.[7] SP consolidated its freight and maintenance operations at the Bayshore Yard; maintenance had previously been performed at two locations: 16th and Harrison, and Mariposa.[54] The yard hump was the second hump constructed on the West Coast[27] (after the classification yard at Roseville).[1]

Steam locomotive maintenance would start in the Roundhouse. Once the locomotive left the Roundhouse, it would move to the Transfer Pit (northwest of the Roundhouse), then be moved sideways on a 78-foot (24 m) long transfer table riding on six rails[7] to line up with a track into the Erecting and Machine Shops, where a gantry crane would pick up the boiler and put it on a railcar to move it 300 feet (91 m) south to the Tank and Boiler Shop for refurbishment.[27] At the height of operations between 1911 and 1958, more than 3,000 were employed at the railyard and shops.[26] The railyard was handling 42,000 cars per month in 1921, and had 1,196 employees earning a monthly average of US$164.31 (equivalent to $2,900 in 2023).[25] As SP's most heavily traveled segment, the railyard handled 22 million gross tons per mile of freight in the 1920s and 46.5 million gross tons per mile during World War II.[25]

The Bayshore Yard site was acquired by Tuntex (now Universal Paragon) in 1989. Universal Paragon has proposed redeveloping the area as the Brisbane Baylands development. As of 2013[update], the only buildings left from the railyard are the Roundhouse (built c.1910, abandoned), the Tank and Boiler Shop (built c.1920, leased to Lazzari Fuel in 1963 and used as a charcoal warehouse), and the Visitacion Ice Manufacturing Plant (built 1924 for Pacific Fruit Express, currently leased to Machinery and Equipment, Inc.).[27][55]

Bayshore Roundhouse

[edit]Southern Pacific Railroad Bayshore Roundhouse | |

Roundhouse in 2012 | |

| Location | Jct. of Industrial Way and Bayshore Ave., Brisbane, California |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 37°42′03″N 122°24′31″W / 37.70083°N 122.40861°W |

| Area | less than one acre |

| Built | 1910 |

| Built by | Southern Pacific Railroad |

| Architectural style | Industrial |

| NRHP reference No. | 10000113[56] |

| Added to NRHP | March 26, 2010 |

The Southern Pacific Railroad Bayshore Roundhouse, at the junction of Industrial Way and Bayshore Ave. in Brisbane, California, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2010.[56][57]

The Bayshore Roundhouse was completed in 1910 and still stands, although it was damaged in an October 2001 fire which destroyed approximately half the roof.[58] Construction on the Roundhouse started in 1908, shortly after the Bayshore Cutoff was completed, and it was one of the first buildings at the new Bayshore railyard.[25]

The Roundhouse encompasses an arc of 108 degrees, and has an inner radius of 125 feet (38 m) and an outer radius of 212 feet (65 m).[25] It has forty stalls, and an on-site powerhouse, north of the Roundhouse, provided steam for locomotive use, burning coal from a bunker 600 feet (180 m) long.[23] Seventeen of the stalls (numbered #24 to #40, clockwise) were inside the building and covered.[26][25] Stalls #1 to #23 were outside whisker tracks, although construction plans, contemporary articles, and the presence of foundation pilings suggest the roundhouse was originally designed to enclose these as well.[7][25] The wall adjacent to stall #40, on the eastern side of the building, contains four sets of windows, and the outer circumference of the building has two sets of windows for each stall. There is one fire wall (between stalls #32 and #33) without windows (which stopped the 2001 fire from destroying the roof of stalls 33–40), and the wall adjacent to stall #24 does not have windows, since it was originally intended to serve as a second interior fire wall.[25]

As originally constructed, the turntable was pneumatically operated with a diameter of 80 feet (24 m).[7] The turntable was enlarged to 110 feet (34 m) in 1941 using steel salvaged from the Pajaro River bridge; with the enlargement, the Roundhouse was capable of handling SP's largest steam locomotives.[26] The fire in 2001 destroyed the roof covering stalls #24 through #32.[25] Today,[when?] it is the last standing brick roundhouse in California,[26] and it was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2010.[56]

Other structures

[edit]The Erecting and Machine Shops (or Backshops) building had a footprint of 130.4 by 449 feet (39.7 m × 136.9 m), and had 15 engine pits, each 55 feet (17 m) in length, with a 120-short-ton (110 t) gantry crane in the erecting portion, and a smaller 15-short-ton (14 t) crane in the machine shops portion.[7] One scene for the film Harold and Maude was filmed at the Bayshore Yard; the Backshops building was used as the studio of Glaucus, the artist who is carving a nude of Maude in ice. That building was demolished in the mid-1980s.[59][60]

The Tank and Boiler Shops ceased operation with the end of steam locomotives in the 1950s, and was leased to the Lazzari Fuel Company in 1963, who use it today to store charcoal.[27]

Other shops in 1921 included the Locomotive Paint Shop; the Planing Mill and Car Repair building, another large shop with a footprint of 185 by 335.5 feet (56.4 m × 102.3 m); and the Freight Car Repair Shed, 117 by 441 feet (36 m × 134 m).[7]

The Visitacion Ice Manufacturing Plant, at the southern end of the Bayshore Yard, was completed in 1924. It was capable of freezing 90 short tons (82 t) of ice per day, and could store 2,300 short tons (2,100 t). It made ice between 1924 and 1955 for Pacific Fruit Express refrigerated cars. The building was sold to the Market Street Van & Storage Company in 1962.[27]

Stations

[edit]From north to south:

- San Francisco Third and Townsend (Closed 1975)

- San Francisco 4th and King

- 22nd Street (between Tunnel 1 and Tunnel 2)

- Paul Avenue (Closed 2005; between Tunnel 3 and Tunnel 4)

- Bayshore (between Tunnel 4 and Tunnel 5)

- Butler Road (Closed 1983)

- South San Francisco

- San Bruno

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "The Bay Shore and Dumbarton Cut-Offs of the Southern Pacific". The Railroad Gazette. XLII (11): 328–331. March 15, 1907.

- ^ a b c "Two Tracks to San Jose". The Evening News. San Jose. May 4, 1900. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ^ "Buys a way out". San Francisco Call. Vol. 75, no. 170. May 19, 1894. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- ^ "Court to pass on nuisance of Mission tracks". San Francisco Call. Vol. 87, no. 86. August 25, 1900. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- ^ "Double Track Of Coast Line". The Deseret News. December 24, 1901. Retrieved July 12, 2016.

- ^ "Rush Double Track To The Garden City". The Evening News. San Jose. May 14, 1902. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Geiger, Charles W. (May 21, 1921). "New Freight and Shop Terminal of Southern Pacific Company at Bayshore". Railway Review. 68 (21): 771–776. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- ^ "New System Will Benefit City". San Francisco Call. Vol. 100, no. 38. July 8, 1906. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- ^ "Railway Bridge Across Narrows at Dumbarton Point". The Evening News. San Jose. September 8, 1906. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ^ "Bay Shore Cutoff Favored by Local Business Men". The Evening News. San Jose. March 12, 1903. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ^ "New Course Desired for Bay Shore Cut Off". The Evening News. San Jose. August 7, 1903. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ^ a b Dunscomb, Guy L. (1963). A century of Southern Pacific steam locomotives, 1862–1962. Modesto, California: Modesto Printing Company. p. 366. LCCN 63-14308. Retrieved July 12, 2016.

- ^ a b "Bay Shore Cut-off Line to be Rushed". Los Angeles Herald. March 4, 1904. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- ^ a b Douglas, Don (2011). "Southern Pacific's Bayshore Yard". The Ferroequinologist. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Guests inspect the new Bay Shore Cutoff". San Francisco Call. Vol. 103, no. 8. December 8, 1907. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- ^ Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 30, 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the MeasuringWorth series.

- ^ Mercer, Lloyd J. (1985). E. H. Harriman: Master Railroader. Boston: Twayne Publishers. p. 74. ISBN 1-58798-160-2. Retrieved June 13, 2018.

- ^ Bevk, Alex (May 29, 2013). "The Lost Railroad Tracks of the Mission and Noe Valley". Curbed San Francisco. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ^ Brandi, Richard; LaBounty, Woody (January 2010). "San Francisco's Ocean View, Merced Heights, and Ingleside (OMI) Neighborhoods, 1862 - 1959" (PDF). Western Neighborhoods Project. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ^ Fredericks, Darold (June 3, 2013). "The History of BART on the Peninsula". San Mateo Daily Journal. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- ^ BART-San Francisco Airport Extension: Final Environmental Impact Report/Final Environmental Impact Statement (Report). Vol. I. Bay Area Rapid Transit District. June 1996. Retrieved January 8, 2018.

- ^ California Fair Political Practices Commission (March 31, 1988). "Application of the conflict of interest provisions of the Political Reform Act" (PDF). Letter to Mr. Robert S. Allen. Retrieved January 8, 2018.

- ^ a b c d "Railroad Rushes Work at Visitacion Bay". San Francisco Call. Vol. 101, no. 45. January 14, 1907. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- ^ a b "Rushing Work at Dumbarton". The Evening News. San Jose. January 16, 1907. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Brandi, Richard (November 9, 2009). Southern Pacific Railroad Bayshore Roundhouse (PDF) (Report). Office of Historic Preservation, California State Parks. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e "Roundhouse" (PDF). San Francisco Trains. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "4: Environmental Setting, Impacts, and Mitigation Measures; Section 4.D: Cultural Resources" (PDF). Brisbane Baylands Draft Environmental Impact Report (Report). City of Brisbane. June 2013. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ^ a b "Bay Shore Cut-Off Is Now Open". The Evening News. San Jose. December 9, 1907. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ^ a b "Bay Shore Cut-off is Nearing Completion". Los Angeles Herald. Associated Press. July 19, 1905. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- ^ "Will build Bay Shore Cut-off". Los Angeles Herald. April 11, 1904. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- ^ "Work begins on Bay Shore Cut-off". Los Angeles Herald. Associated Press. October 27, 1904. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- ^ "Earthquake Shock About The Bay Not Felt In San Jose". The Evening News. San Jose. December 1, 1904. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ^ "Work is begun on big tunnel". San Francisco Call. Vol. 97, no. 141. April 19, 1905. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- ^ "Rapid work on tunnel". San Francisco Call. Vol. 97, no. 151. April 28, 1905. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- ^ "Rushing work on the tunnels". San Francisco Call. Vol. 97, no. 159. May 6, 1905. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- ^ "Rushing work on the tunnel". San Francisco Call. Vol. 97, no. 166. May 13, 1905. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- ^ "Work being rushed on the big tunnels". San Francisco Call. Vol. 98, no. 17. June 17, 1905. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- ^ "Rain Damages Roadbed". San Francisco Call. Vol. 99, no. 84. February 22, 1906. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- ^ "Quake terrifies men in railroad cut-off tunnel". San Francisco Call. Vol. 99, no. 153. May 2, 1906. Retrieved April 3, 2018.

- ^ Fredricks, Darold (December 17, 2012). "Southern Pacific Railroad". San Mateo Daily Journal. Retrieved April 3, 2018.

- ^ "Bay Shore Cut-Off to be completed in January". Sacramento Union. No. 181. August 21, 1906. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- ^ "To Spend Millions for Cut Off". The Evening News. San Jose. July 23, 1907. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ^ "Work On Cut-off Is Delayed". The Evening News. San Jose. October 9, 1907. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ^ "Cut-Off to Open Next Saturday". The Evening News. San Jose. November 6, 1907. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ^ a b "Bay Shore Cut-Off of the Southern Pacific". The Railroad Gazette. XXXVII (23): 566. November 18, 1904.

- ^ a b c d "Construction on the Bay Shore Line of the Southern Pacific Co". The Railway and Engineering Review. XLVI (42): 806–809. October 20, 1906. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- ^ "Terminal site of new road". San Francisco Call. Vol. 99, no. 32. January 1, 1906. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ Carlsson, Chris. "Potrero Commons 18th-Wisconsin". FoundSF. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ "Southern Pacific Company Has Conquered Water Spring". Red Bluff News. No. 79. June 9, 1911. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- ^ Garrido, Angel (2012). "Modeling S.P. Tunnel Structures". Modeling the SP. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ^ Booker, B.W. (March–April 1956). "Freeways In District IV" (PDF). California Highways and Public Works. 35 (3–4): 7. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

The over water fill section between the completed freeway at Third Street in San Francisco southerly to Candlestick Point and across the open water of an arm of San Francisco Bay to Sierra Point and connecting with the completed freeway near Butler Road, in South San Francisco is the only portion of the freeway remaining to be completed between the Bay Bridge and just north of Redwood City.

- ^ Booker, B.W. (March–April 1957). "Freeways In District IV" (PDF). California Highways and Public Works. 36 (3–4): 3–4. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

CAPTION: Bayshore Freeway construction at Sierra Point looking southerly. Note S.P.R.R. relocation. Tunnel right center eliminated.

- ^ "Bold Venture: Open-water Highway Project Is Dedicated to Traffic" (PDF). California Highways and Public Works. Vol. 36, no. 7–8. July–August 1957. pp. 57–58, 72. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- ^ "New Bay Shore Yards of the Southern Pacific at San Francisco". Railroad Gazette. XLII (1): 12–13. January 4, 1907. Retrieved May 18, 2018.

- ^ "3: Project Description" (PDF). Brisbane Baylands Draft Environmental Impact Report (Report). City of Brisbane. June 2013. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ^ a b c "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. November 2, 2013.

- ^ Richard Brandi (November 9, 2009). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Southern Pacific Railroad Bayshore Roundhouse (DRAFT)" (PDF). California Office of Historic Preservation. Retrieved October 26, 2018. With historic photos and eight photos from 2009.

- ^ Lipps, Jeremy (November 7, 2013). "#CALTRAIN150: Rise and Fall of the Bayshore Roundhouse". Peninsula Moves. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ^ CitySleuth (November 8, 2015). "Harold and Maude - Glaucus's Studio". Reel SF. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ^ Meretzky, Steve. "Glaucus' studio". boffo. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

External links

[edit]- Baltimore, J. M. (July–December 1907). "Industrial Progress: Pacific Coast Letter". Industrial Magazine. 7 (2): 153–156. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- Nolte, Carl (January 4, 2014). "Following ghost tracks of long-forgotten railroad". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- Baltimore, J. Mayne (September 1907). "Western Railroad Activities". Locomotive Firemen's Magazine. 43: 319. Retrieved July 12, 2016.

- Rice, Walter; Echeverria, Emiliano (January–February 2001). "When Steam Ran on the Streets of San Francisco, Part II: San Francisco's Main Stem – Market Street". Live Steam. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- "Conquest of the Peninsula". San Francisco Call. Vol. 99, no. 38. January 7, 1906. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- Signor, John R. (1995). Southern Pacific's Coast Line. Lompoc, California: Signature Press. ISBN 0-9633791-3-5. Retrieved January 16, 2017.

Railyard and roundhouse

[edit]- Gibson, E.O. "Southern Pacific In San Francisco: Bayshore Roundhouse". wx4.org. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- Hart, Cris (June 7, 2017). "The Brisbane Bayshore Roundhouse" (PDF). City of Brisbane. Retrieved May 18, 2018.

- Thompson, Evan; Barringer, Daisy (April 16, 2015). "This 105-year-old abandoned train yard in SF? Incredible". Thrillist San Francisco. Retrieved April 6, 2018.