Battle of Zarumilla

| Battle of Zarumilla | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Ecuadorian–Peruvian War | |||||||||

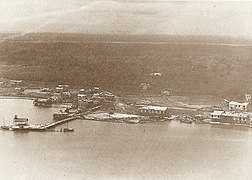

Peruvian bombardment of Arenillas | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

37+ killed and wounded 1 destroyer damaged[d] |

1,334 killed and wounded 200 Ecuadorians captured 1 gunboat damaged[e] 1 boat captured Several weapons and military equipment seized captured | ||||||||

| 2 Peruvian civilians killed[1] | |||||||||

The Battle of Zarumilla was a military confrontation between Peru and Ecuador that took place from July 23 to 31 during the 1941 Ecuadorian–Peruvian War.[1][15]

Background

[edit]Hostilities between Peru and Ecuador began on July 5, 1941, when fire was exchanged between both parties. The events themselves, however, are disputed. According to Ecuador, a group of Peruvians, including policemen, crossed the Zarumilla River into Ecuadorian territory. The Peruvian policemen are then said to have fired first when a border patrol was spotted.[16] According to Peru, the Ecuadorian Army shot first at local Civil Guard troops, which exchanged fire for 30 minutes, holding back a potential advance and waiting for reinforcements.[17][18] After July 5, hostilities along the border continued. As a result, on the night of July 6, the senior commander of the Ecuadorian Army ordered the formation of the 5th Infantry Brigade in El Oro, under the command of Colonel Luis Rodríguez.[19]

Battle

[edit]The Peruvian offensive began on July 23, being carried out by the newly formed Northern Army Detachment headed by General Eloy G. Ureta with the purpose of pushing north into El Oro Province to prevent more skirmishes along the disputed border.[1]

Quebrada Seca

[edit]On July 23, 1941, the 41st Peruvian Squadron took off from Tumbes to fulfill a mission, under the command of Lieutenant Commander Antonio Alberti and made up of Lieutenants Fernando Paraud, José A. Quiñones and Manuel Rivera, aboard their North American NA-50 or Toritos fighter planes. The mission consisted of bombing the Ecuadorian post of Quebrada Seca, where they had concentrated the bulk of their anti-aircraft artillery and placed machine guns.[1]

According to Peruvian accounts, instead of parachuting to safety, Quiñones chose to crash his damaged aircraft into the Ecuadorian position, rendering the battery out of action. This version of events has been subsequently called into question by Ecuadorian military authorities, who have stated that there were no anti-aircraft guns in the area. The other planes that made up Squadron 41 continued with their mission and carried out a subsequent attack, returning to Tumbes.[20]

Jambelí

[edit]The Peruvian destroyer Almirante Villar set sail from Zorritos with the mission of entering Ecuadorian waters and carrying out patrolling and reconnaissance tasks in the area. It was then that, being in the vicinity of the Jambelí channel, the Ecuadorian gunboat Abdón Calderón was spotted. The Ecuadorian ship, which was in transit to Guayaquil, turned 180º with respect to its course as soon as it recognized the Peruvian ship, fleeing towards Puerto Bolívar while firing shots. Admiral Villar did the same, maneuvering in circles avoiding getting too close to the coast due to its shallow depth. After 21 minutes of both sides exchanging fire, the incident ended.[21][4]

Puerto Bolívar

[edit]On July 23, Peruvian aircraft carried out a strategic bombing of the port city. On the next day, aircraft returned to attack the Aviso Atahualpa patrol boat, located in the docks of the city. The fact that the patrol boat was the target as well as the subsequent defense of it carried out by Ecuadorian troops prevented valuable explosives located nearby from being attacked and ignited.[7]

On July 28, Peruvian submarines BAP Islay (R-1) and BAP Casma (R-2) carried out a reconnaissance mission at the mouth of the Jambelí Strait in order to detect the presence of artillery. The following day, cruisers Coronel Bolognesi and Almirante Guise, during a patrol in front of the Jambelí Strait, bombed Punta Jambelí and Puerto Bolívar, in preparation for the Peruvian advance on El Oro.[1]

On July 31, prior to the cease fire that was to be effective on that date, an order was given to capture the city of Puerto Bolívar, which was accomplished using paratroopers from the newly formed Paratrooper Company of the Peruvian Air Force.[1] The use of said paratroopers was decisive in the capture of the city and served as a surprise factor since, only a handful of countries had a unit of said type, such as Germany with their Fallschirmjäger, making Peru the first country in the Western Hemisphere to deploy paratroopers, being followed by Argentina in 1944.[22][23][24]

Aftermath

[edit]After the ceasefire, a Civil Administration was established in the occupied Province of El Oro by Peru.[1] A month later, on October 2, a bilateral ceasefire was signed which also established a demilitarized zone between both states.[25]

By the time the ceasefire had been accepted, the cities bombarded by Peru included Santa Rosa, Machala and Puerto Bolívar. Peruvian aircraft had reached Guayaquil in at least two different occasions, but the squadron sent to the city limited itself to dropping propaganda leaflets, which were republished by Peruvian newspapers La Industria and El Tiempo.[26]

A fire began in Santa Rosa on August 1, 1941, which destroyed over 120 houses.[27]

The government of Ecuador, led by Dr. Carlos Alberto Arroyo del Río, signed the Rio de Janeiro Protocol on January 29, 1942, with which Ecuador officially renounced its claim to a sovereign outlet to the Amazon River.[1]

On February 12, 1942, Peruvian troops vacated the Ecuadorian province of El Oro.[28]

Gallery

[edit]-

Peruvian troops during a battle in Tembleque Island

-

A captured Ecuadorian outpost in Chacras.

-

The Peruvian flag flies over Quebrada Seca.

-

Reconnaissance photo of Puerto Bolívar prior to its invasion.

-

Bombing of Ecuador by Peruvian aircraft

-

The town of Santa Rosa prior to its invasion

-

Santa Rosa during the fire.

-

The Ecuadorian coast during the Peruvian occupation on the 31st.

-

Peruvian troops in Puerto Bolívar during the occupation. Future president Manuel A. Odría can be seen among them.

See also

[edit]- Alerta en la frontera, a documentary film filmed during the war that went unreleased until 2014 due to the Rio de Janeiro Protocol[29]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Monteza Tafur, Miguel (1979). El Conflicto Militar del Perú con el Ecuador. Editorial Universo S.A. pp. 124–166, 171–194.

- ^ Chávez Valenzuela, Gral. Brig. EP Armando (1998). Geopolítica, Tensiones Territoriales y Guerra con Ecuador (in Spanish). Lima: La Breña. p. 87.

- ^ "Gral. Div. JOSÉ DEL CARMEN MARÍN ARISTA: Fundador y Primer Director del CAEN-EPG". Centro de Altos Estudios Nacionales – Escuela de Posgrado.

- ^ a b (in Spanish) – via Wikisource.

- ^ Nomberto, Víctor R. "Guerra de 1941". Blog PUCP.

- ^ Avilés Pino, Efrén (20 May 2016). "Cmdt. Rafael Morán Valverde". Enciclopedia del Ecuador.

- ^ a b Macías Núñez, Edison (2012). EL EJÉRCITO ECUATORIANO EN LA CAMPAÑA INTERNACIONAL DE 1941 Y EN LA POST GUERRA (in Spanish). Quito: Centro de Estudios Históricos del Ejército. pp. 97–101.

- ^ a b Historia Militar del Ejército del Ecuador (PDF). Ejército del Ecuador. 2019. pp. 5–8.

- ^ "Quiñones inédito". El Peruano. 2019-07-23.

- ^ "Conozca el avión restaurado por la FAP, similar al que piloteó Quiñones". El Peruano. 2021-07-25.

- ^ a b c Julca-Núñez, Héctor (2017). Vencedores del 41: Campaña Militar Contra Ecuador (PDF) (in Spanish). Piura: University of Piura. pp. 61, 108–110.

- ^ a b J. Quiñones: 100 años (in Spanish). Lima: Fuerza Aérea del Perú. 2014. pp. 132–135.

- ^ a b Naranjo Salas, Wagner (2020). Honor y gloria. La resistencia del cañonero Abdón Calderón y el patrullero Aviso Atahualpa. Revista de Investigación Académica y Educación.

- ^ "OFICIALES Y SOLDADOS JAPONESES SECUNDAN LA AGRESION PERUANA A NUESTROS DESTACAMENTOS". El Comercio. 1941-07-24. p. 1.

- ^ Tamayo Herrera, José (1985). Nuevo Compendio de Historia del Perú. Editorial Lumen. p. 349.

- ^ Rodríguez, 1955: 168

- ^ Colección Documental del Conflicto y Campaña Militar con el Ecuador en 1941. Vol. III. Lima: Centro de Estudios Históricos Militares del Perú. 1978. pp. 773–774.

- ^ "Conflicto con el Ecuador: nuestras fuerzas rechazan una nueva agresión en la frontera de Zarumilla". El Comercio. 2021-07-23.

- ^ Rodríguez, 1955: 173

- ^ "Jose Quiñones - Peruvian Kamikaze Hero".

- ^ Rodríguez Asti, John (2008). Las Operaciones Navales durante el Conflicto con el Ecuador de 1941: apuntes para su historia (in Spanish). Lima: Dirección de Intereses Marítimos e Información. p. 44. ISBN 978-9972764172.

- ^ "Campaña Militar del 41". Escuela Superior de Guerra del Ejército. Archived from the original on 2022-03-19. Retrieved 2022-02-25.

- ^ Theotokis, Nikolaos (2020). Airborne Landing to Air Assault: A History of Military Parachuting. Pen and Sword Books. pp. 137–138. ISBN 9781526747020.

- ^ "Asalto aéreo a Puerto Bolívar". Caretas. No. 1375. 1995-08-01.

- ^ Estudio de la cuestión de límites entre el Perú y el Ecuador (in Spanish). Peru: Ministry of War of Peru. 1961. pp. 71–72.

- ^ Ríos Huayama, Cristhian Fabián (2021). Estudio del conflicto Perú-Ecuador (1941-1942) con base en el análisis hemerográfico del diario La Industria (enero 1941 - febrero 1942) (PDF) (in Spanish). Piura: University of Piura. pp. 118–119.

- ^ "Historia - Cuerpo de Bomberos Municipal del Cantón Santa Rosa". Cuerpo de Bomberos Municipal del Cantón Santa Rosa.

- ^ "29 de enero de 1942". El Universo. 2016-07-03.

29.I.1942: "Hoy a las 2 a. m. se Firmó el Acuerdo Ecuatoriano-Peruano: Las Fuerzas Peruanas Saldrán Dentro de 15 Días de Nuestros Territorios (Today at 2 a.m. the Ecuadorian–Peruvian Agreement was signed: Peruvian Troops will leave our territories in 15 days)

- ^ Barrow, Sarah (2018). Contemporary Peruvian Cinema: History, Identity and Violence on Screen. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 192. ISBN 978-1838608200.

Bibliography

[edit]- Rodríguez S., Luis (1955). La agresión peruana documentada. Quito: Casa de la Cultura ecuatoriana.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Posthumously ascended to Major.[8]

- ^ Posthumously ascended to Captain.[8]

- ^ While Japanese Peruvians were considered a foreign element by Ecuador due to their recent inmigration into Peru, the participation of mercenaries from Japan itself was also alleged.[14]

- ^ According to Ecuador.

- ^ According to Peru.