Battle of Petrovaradin

| Battle of Petrovaradin | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Austro-Turkish War (1716–1718) | |||||||

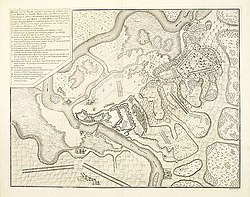

Battle of Peterwardein by Georg Philipp Rugendas | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 60,000 men[3][4][b] | 150,000 men[3][5][c] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 4,500 killed and wounded[7][d] | 20,000 killed[9][e] | ||||||

The Battle of Petrovaradin also known as the Battle of Peterwardein, took place on 5 August 1716 during the Austro-Turkish War when the Ottoman army besieged the Habsburg-controlled fortress of Petrovaradin on the Military Frontier of the Habsburg monarchy (today Novi Sad, Vojvodina, Serbia). The Ottomans attempted to capture Petrovaradin, the so-called Gibraltar on the Danube, but experienced a great defeat by an army half the size of their own, similar to the defeat they had experienced in 1697 at the Battle of Zenta. Ottoman Grand Vizier Damad Ali Pasha was fatally wounded, while the Ottoman army lost 20,000 men and 250 guns to the Habsburg army led by Field Marshal Prince Eugene of Savoy.

The Austrians consolidated this victory by marching into the Banat and conquering Temesvár, the last remaining Turkish fortress in Hungary, followed by Belgrade.[11]

Background

[edit]In the summer of 1715, the Ottoman Empire started to reclaim the Peloponnese, which had been ceded to the Republic of Venice by the Karlowitz Treaty in 1699. The Turks, led by Grand Vizier Damat Ali Pasha, easily reconquered the Venetian Kingdom of the Morea (the Greek Peloponnese). Having made an alliance with Venice in April 1716, Austria demanded full withdrawal from the Ottoman Empire as well as compensation to Venice for the continued violation of the stipulations of the Karlowitz treaty; the Ottoman grand-vizier, confident that he could defeat the Habsburgs and even regain Hungary, responded by declaring war on 15 May 1716.[12]

Prelude

[edit]Damat Ali Pasha, the Sultan's son-in-law, left Constantinople with a 120,000 strong Turkish Army taking nearly three months to cover the 710 kilometres (440 miles) to Belgrade. There he consolidated an Ottoman force of 150,000 soldiers, at the core of which were 41,000 elite Janissaries and 30,000 Sipahi Ottoman cavalry, along with Tatar and Wallachian auxiliaries.[2] They crossed the Sava at Zemun on 26 July, and moved on the right bank of the Danube towards Sremski Karlovci in Habsburg territory.[13]

The commander of the Austrian forces, Prince Eugene of Savoy, decided to engage the Ottomans at Petrovaradin. Eugene arrived at the fortress on 9 July. He had arranged for the construction of a fortified encampment within the Petrovaradin fortress which was nicknamed Gibraltar on the Danube.[14] Eugene set the 60,000-strong Imperial army on the march from their quarters in Futog.[3] Inside the Petrovaradin garrison were 8,000 men consisting primarily of Serbs. Serving in the Austrian army were Croatian and Hungarian infantry and cavalry regiments (approx. 42,000 men); Serbian border soldiers from Vojvodina; and the auxiliaries from Württemberg.[1] On 2 August, the first skirmish between the Imperial vanguard and Ottoman horsemen occurred when Field Marshal Count János Pálffy, with a small body of men, lead a group on reconnaissance but ran into more than 10,000 Turkish cavalry in the area of Karlowitz. The Austrian forces managed to make it back to camp but lost 700 men in the engagement and Field Marshal Count Siegfried Breuner was captured.[13] By the next day, the Grand Vizier had reached Petrovaradin and immediately dispatched 30,000 Janissaries against the imperial positions. The Janissaries dug saps and began to bombard the fortress. The bulk of the Austrian army crossed the Danube on 4 August by two pontoon bridges of boats, after which on the night of 4–5 August they encamped south of Petrovaradin. Their arrival was made under the cover of an unusual summer snowstorm.[15]

Battle

[edit]

Given their numerical disadvantage, Prince Eugene decided to station his men with one flank on the Danube and the other on the fortifications, using an entrenchment left from a battle that occurred outside Petrovaradin's southern walls. A storm had damaged the bridges on the Danube delaying the deployment of the Imperial forces. Eugene took a high position from where he could command his troops.[16]

Ready for battle were 64 battalions, 187 cavalry squadrons and 80 guns.[10] The infantry behind the foremost entrenchment formed the centre in three lines under the command of Field Marshal Sigbert Heister and Guido Starhemberg; to the left most of the cavalry under János Pálffy; and on the right wing a separate group of four cavalry regiments under Sigbert Heister and General of Cavalry Ebergenyi. A completely independent group of six battalions outside the ramparts, under the command of Alexander von Württemberg, acted as a liaison between the centre army and the left wing cavalry, outside the ramparts, ready to advance in support.[10] The Ottoman commander, feeling confident after defeating the reconnaissance group, demanded the surrender of the fortress.[13] Eugene responded, "We will attack!"[17]

On 5 August at seven o'clock in the morning, Eugene launched the Austrian offensive with a massive attack supported by frigates in the Danube river.[3] The Imperial left wing infantry of Württemberg easily took the first Ottoman positions and a battery of ten guns while the cavalry of Pálffy drove the opposite riders from the field. At the same moment, the Imperial centre ran into over-powering numbers of Janissaries who managed to push Starhemberg's troops back into their entrenchments. Another infantry charge from Heister this time was again repulsed despite help from the Imperial cuirassiers; when the Austrian lines started breaking up, the Janissaries decided to push forward at the Habsburg centre but in doing so exposed both their flanks.[18]

At this decisive moment, Eugene sent Ebergenyi's cavalry to attack the left wing while ordering Württemberg's battalions to attack the right supporting by cuirassiers. At the same time Eugene sent the reserve of Lõffelholz to secure the centre that was now moving forward. Meanwhile, the cannons of the fortress started ripping into the Turkish lines. János Pálffy with the Habsburg cavalry pushed back the Ottoman cavalry blocking simultaneously the escape route of the Janissaries, the Habsburg infantry moved in after the remaining Turks.[7] Eugene launched a general attack leading the charge himself against the Ottoman's encampment. Damat Ali Pasha who, at the head of his bodyguard, plunged into the battle in a desperate charge, was killed,[f] as well as the governors of Anatolia and Adana, Türk Ahmed Pasha and Hüseyn Pasha, along with 20,000 men.[20] The Imperial losses were 3,695 common soldiers and 469 officers.[6] The battle was over by 2 pm. Eugene of Savoy had taken only five hours to rout the Ottomans. Eugene wrote his report on the battle from Damad Ali's tent, reporting the seizure of 172 cannons, 156 banners, and five horse-tail standards as well as the Turkish war chest.[7]

Aftermath

[edit]The Austrian Army spent 5 and 6 August on the battlefield, on 7 August it crossed the left bank of the Danube. A cavalry group made up of 1,400 riders, including 200 hussars, under General Carl Graf von Eckh set out in pursuit of the Turks.[1]

Within 20 days, Eugene had marched his army into the Banat, subduing the countryside with the help of Serbian irregulars[21] and besieged the fortress of Temeşvar, which had been in Ottoman hands since 1552; on 16 October, after a siege of 43 days, Temeşvar surrendered. It was followed by Belgrade, which fell to the Habsburg armies on 18 August 1717, when once again Eugene led the Austrian army to victory against superior forces, advancing for the first time deep into Ottoman territory.[22]

Legacy

[edit]A pilgrimage church was built at Tekije (part of Petrovaradin), on the hill overlooking the battlefield. It houses the shrine of Our Lady of the Snows. The site is a place of pilgrimage every 5 August.[14] At the place of the battlefield on Vezirac hill in Petrovaradin, a monument that honours the victory of the Austrian army was erected in 1902, designed by Zagreb architect Hermann Bollé.[23]

-

Church of St Mary of the Snows

-

Turkish state tent captured in the battle, on display in the Museum of Military History, Vienna

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ As part of auxiliary troops[2]

- ^ Included Hungarian and Croat Hussars[2]

- ^ Of which 40,000 were Janissaries, 30,000 Sipahis, and the rest being Tartars, Walachians and troops of Asia and Egypt[6]

- ^ Habsburg battle casualties included the deaths of numerous Field Marshals, most notably; Siegfried Breuner, Bertram Gehlen, Hannibal Schilling, Friedrich Lanken, Johann Wallenstein, and Ernst Lanckhen.[8]

- ^ The Ottoman high number likely included camp followers indiscriminately killed in the chaotic rout; the Janissaries alone suffered between 6,000 and 10,000 casualties[10]

- ^ Damad Ali was buried in the Belgrade Fortress, Kalemegdan, his tomb is known as Damat Ali-Paša's Turbeh[19]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c A military history of the Hungarian nation.

- ^ a b c McKay, Baker & von Savoyen 1977, p. 223.

- ^ a b c d Tucker 2010, p. 721.

- ^ Campbell 1737, p. 216.

- ^ Campbell 1737, p. 214.

- ^ a b Harris 1841, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Ágoston 2011, p. 104.

- ^ Andreas Thürheim: Gedenkblätter aus der Kriegsgeschichte der K. K. oesterreichischen Armee. Vol. 2. Verlag der Buchhandlung für Militär-Literatur, Vienna, 1880, p. 480.

- ^ Harbottle & Bruce 1979, p. 197.

- ^ a b c Heinrich Dyck 2020.

- ^ Finkel 2012, p. 647.

- ^ Shaw & Shaw 1976, p. 232.

- ^ a b c Setton 1991, p. 435.

- ^ a b Wheatcroft 2009, p. 233.

- ^ Urban & Showalter 2013, p. 39.

- ^ Henderson 2002, p. 224.

- ^ Henderson 2002, p. 223.

- ^ Upton 2017, p. 41.

- ^ Srđan Rudić et al. 2018, p. 480.

- ^ McKay, Baker & von Savoyen 1977, p. 160.

- ^ Aksan 2014, p. 101.

- ^ Setton 1991, p. 436.

- ^ I love Novi Sad 2016.

References

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- Ágoston, Gábor (2011). "Punic Politics, Economy, and Alliances, 218–201". In Ingrao, Charles; Samardzi, Nikola; Pesalj, Jovan (eds.). The Peace of Passarowitz, 1718. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-594-8.

- Aksan, V. (2014). Ottoman Wars, 1700–1870: An Empire Besieged. Modern Wars In Perspective. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-88403-3.

- Campbell, J. (1737). The Military History of the Late Prince Eugene of Savoy, and of the Late John Duke of Marlborough. J. Bettenham. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- Finkel, C. (2012). Osman's Dream: The Story of the Ottoman Empire 1300–1923. John Murray Press. ISBN 978-1-84854-785-8.

- Harbottle, T.B.; Bruce, G. (1979). Harbottle's Dictionary of Battles. Granada. ISBN 978-0-246-11103-6.

- Harris, T.M. (1841). Biographical memorials of James Oglethorpe.

- Henderson, N. (2002). Prince Eugen of Savoy: A Biography. A Phoenix Press Paperback. Phoenix. ISBN 978-1-84212-597-7.

- McKay, D.; Baker, D.V.; von Savoyen, E.P. (1977). Prince Eugene of Savoy. Men in office. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0500870075.

- Setton, K.M. (1991). Venice, Austria, and the Turks in the Seventeenth Century. American Philosophical Society. ISBN 978-0-87169-192-7.

- Shaw, S.J.; Shaw, E.K. (1976). History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey: Volume 1, Empire of the Gazis: The Rise and Decline of the Ottoman Empire 1280–1808. Cambridge books online. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29163-7.

- Srđan Rudić, S.A.; Amedoski, D.; The Institute of History, B.; Yunus Emre Enstitüsü, T.C.C.B.; Ćosović, T. (2018). Belgrade 1521–1867. Institute of History Belgrade. ISBN 978-86-7743-132-7.

- Tucker, S. (2010). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-667-1.

- Upton, G. (2017). Prince Eugene of Savoy. Jovian Press. ISBN 978-1-5378-1165-9.

- Urban, W.; Showalter, D. (2013). Bayonets and Scimitars: Arms, Armies and Mercenaries 1700–1789. Pen & Sword Books. ISBN 978-1-4738-2971-8.

- Wheatcroft, A. (2009). The Enemy at the Gate: Habsburgs, Ottomans, and the Battle for Europe. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-7867-4454-1.

Websites

[edit]- "Bánlaky József". A military history of the Hungarian nation (in Hungarian).

- "Roman Catholic church of the Snow Lady on Tekije". I love Novi Sad. 1 July 2016.

- Heinrich Dyck, Ludwig (7 July 2020). "'We will attack!' Prince Eugene at Peterwardein". Ludwig H. Dyck's Historical Writings.

Further reading

[edit]- Pach, Z. P. (1985). History of Hungary 1526–1686. History of Hungary in 10 volumes; vol. 1 (in Hungarian). Akadémiai Kiadó.

External links

[edit]- 1716 in the Habsburg monarchy

- 1716 in the Ottoman Empire

- 18th-century battles

- Austro-Turkish War (1716–1718)

- Battles involving Austria

- Battles involving Habsburg Croatia

- Battles involving Hungary

- Battles involving Serbia

- Battles involving Serbian Militia

- Battles involving the Crimean Khanate

- Battles involving the Ottoman Empire

- Battles involving Württemberg

- Conflicts in 1716

- History of Syrmia

- Military Frontier

- Military history of Serbia

- Military history of the Habsburg monarchy