Battle of Havana (1748)

| Battle of Havana (1748) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of Jenkins' Ear | |||||||

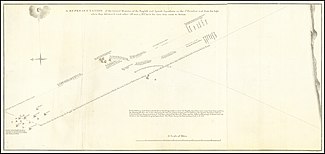

Sir Charles Knowles's Engagement with the Spanish Fleet off Havana, Richard Paton | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 5 fourth-rates |

4 fourth-rates, 1 frigate | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 59 killed and 120 wounded[1] |

1 ship captured 1 ship destroyed 1 ship heavily damaged[2] 86 dead and 197 wounded[3] 470 captured[1] | ||||||

The Battle of Havana was a naval engagement that took place between the British Caribbean squadron and a Spanish squadron based near Havana during the War of Jenkins' Ear.[4] The battle occurred on the morning of the 12th and ended on 14 October 1748. The belligerents consisted of two squadrons under the command of Admiral Don Andres Reggio of the Spanish Navy and Admiral Sir Charles Knowles of the Royal Navy, respectively.[5] The British succeeded in driving the Spanish back to their harbour after capturing the Conquistador and ran the vice-admiral's ship Africa on shore, where she was blown up by her own crew after being totally dismasted and made helpless. Although the advantage had clearly been with Knowles, he failed to use this to deliver a decisive blow.[6] The battle was the last major action in the War of Jenkins' Ear which had merged with the larger War of the Austrian Succession.[4]

Background

[edit]By 1747 actions fought between Great Britain and Spain in the America's during the War of Jenkins' Ear had led to stalemate; British forces had failed to subdue any of the Spanish colonies and had lost heavy casualties as a result, while Spain had also failed to subdue any British colonies.[7][8] Naval warfare did not play a significant role in the outcome of the War of the Austrian Succession. There were however a few individual actions of importance.[9] The rise to prominence of First Baron George Anson of the Royal Navy through his raiding of Spanish possessions off the West Coast of the Americas in 1740 during his circumnavigation of the globe.[10] Britain's blockade of Toulon which effectively paralysed a combined Franco-Spanish fleet based there and also interdicted this ports potential role as a base for convoy activity until the Battle of Toulon on 11 February 1744.[11] This battle resulted in the retirement of the blockading fleet by its commander.[12] A planned French invasion of England was stopped by severe weather and the Royal Navy in March and April of the same year but after this naval operations were tied mainly with privateers.[13]

In April 1747 Admiral Sir Charles Henry Knowles had become commander in chief on the Jamaica station but had failed to subdue Santiago de Cuba the following year.[14] After having his ships had refitted at Port Royal Knowles sailed on a cruise in search of Spanish treasure convoys hoping to intercept the Spanish treasure fleet off Cuba before news came of a final peace between Spain and Britain.[15] By this time news of the peace between France and Britain had arrived but no news had been received as of the latter's peace with Spain so Knowles sailed on.[6]

On 30 September he fell in with HMS Lenox, under Captain Charles Holmes, who reported that he had encountered a Spanish fleet some days earlier.[14] Admiral Don Andrés Reggio, commanding the Havana Squadron, left Havana on 2 October with the intention of protecting Spain's shipping lanes from raids by British forces.[5] His undermanned crews supplemented by a regiment of troops and several hundred conscripts on board.[2] The wind was easterly and varied in intensity throughout the day but diminished significantly around mid-day and picked up again in early afternoon.[15]

Battle

[edit]

On the morning of 1 October 1748 the Havana Squadron under the command of Admiral Don Andres Reggio was sailing North in a disorganized formation off of Havana.[15] Reggio sighted what he believed to be a Spanish convoy and thus with the intention of offering escort to this "squadron" he signalled his command to bear directly on a course to intercept it. Around the same time Admiral Sir Charles Henry Knowles, commanding the British Jamaican squadron, sighted a formation of vessels on a course directly towards him and immediately signalled his own squadron to form line ahead bearing North.[6] His intention was to put sufficient distance between himself and the Havana Squadron which would enable him to gain the weather gauge and close in.[15]

Reggio realized the convoy he had sighted was in actuality the British Jamaican squadron.[5] Immediately he signalled his command to steer to leeward to facilitate the formation of a line ahead bringing him to almost the same course as Knowles.[15] The result of this however meant that he had lost the weather gauge whilst Knowles on the other hand was in a favourable position to obtain it.[16] Knowles gave the signal for the ships in his line to "lead large" with the Spanish on a more convergent course.[17] With the afternoon change in the wind the two leading ships Canterbury and HMS Warwick in Knowles' line drifted within long range of Reggio's centre which then opened fire on them. Knowles had issued standing orders to his entire command to hold their fire but despite this the lead ships returned the fire of the Spanish.[17]

Due to the slowness of Warwicks progress Knowles ordered HMS Canterbury to pass her at 3pm.[18] However it was not until 4pm that the Knowles' flagship HMS Cornwall, and HMS Lenox entered the engagement.[17] This time the combined British ships battered the Spanish and inflicted heavy damage on Conquistador which had soon lost fore and mizzen masts and could only manoeuvre in a small way.[18][19]

Cornwall held its fire until shortly after 4pm when it comes within pistol range and unleashed a broadside into Reggio's Africa.[20] Ahead, HMS Strafford poured broadsides into Conquistador while Lenox joined the action from astern.[2] At 4:30pm HMS Strafford came up close and fired a devastating broadside into the Conquistador; after which she was unable to reply.[5] Within less than an hour Conquistador was battered out of the Spanish line, its captain and two lieutenants lying dead and so soon after struck to Strafford before another broadside could any more damage.[2] Strafford had failed however to send any boats to take possession of her and Reggio recognized this fact and forced Conquistador to re hoist her colours by firing on her from his flagship Africa.[20] HMS Cornwall came up in support with an angry Knowles along with Canterbury - finally Conquistador again struck her colours to Cornwall.[17] Canterburys captain however later claimed that Conquistador had struck to her subsequent to her entrance into the battle.[21] HMS Warwick finally appeared ready to overtake the Spanish by 5:30pm and with this every Spanish ship attempted to save themselves, Strafford and Canterbury attempted to rest away Africa while HMS Tilbury and HMS Oxford pursued the vice flag Invencible.[2][19]

By 9:00pm Invencible appeared silenced, but the British were too weak to prevent its escape.[2] HMS Cornwall having been slowed down by the loss of her fore topsail but Strafford and Canterbury pounded Africa until its main- and mizzenmasts fell.[22] However, with night falling fast the Royal Navy ships were unable to pursue so they broke off at 11pm to begin setting up jury rigging and clawed back out to sea.[2][5]

Of Regio's Squadron, four ships returned to Havana's harbour whilst Conquistador had been captured during the action Invincible had suffered heavy damage and avoided capture by a very narrow margin.[22] Africa, the flagship, was dismasted and badly damaged that she retreated into a small bay 25 miles East of Havana to make repairs.[2] Knowles with a lead part of his squadron Cornwall and Strafford headed Eastward on 14 October and soon discovered her and opened fire.[19] The stranded crew cut Africa's cables set her on fire and ran on her on shore; an hour later further helped by British cannon fire she blew up.[6][23]

Aftermath

[edit]

Knowles then reunited with the rest of his ships but before any action could be planned a Spanish sloop was intercepted where news was received of the Treaty of Aix la Chapelle and that the war in Europe was over.[5][21] Knowles dropped the Spanish prisoners on Cuba and set sail towards Jamaica with his lone prize.[22]

The Battle of Havana demonstrated the importance of tactical cohesion within a unit.[22] Due to a lack of such cohesion Knowles squadron was not able to come to a close engagement quickly enough.[14] If Regio had so desired he could have easily evaded the British squadron by retiring to the west.[17] The British squadron also fired on the Spanish too soon at too great a range. Casualties aboard the four surviving Spanish ships were more than 150 dead and a like number seriously wounded.[2]

Both commanders, Knowles and Reggio, were reprimanded by their respective commands for their conduct during the engagement, in Knowles' case for not bringing his full fleet to bear and achieving a total rout.[22] Knowles vilification of the Captains under his command, excepting David Brodie of the Strafford and Edward Clark of the Canterbury, after this action resulted in their petitioning the Admiralty for his court-martial.[4] He had managed to force and win the battle and was only reprimanded as a result of the proceedings.[21] Although[clarification needed] Knowles was to suffer a mixed reputation as a result of the battle he eventually attained the rank of admiral in 1758.[14]

Regio was Court martialed by Spanish Naval authorities on thirty separate counts dealing with virtually every aspect of the battle and in particular with the destruction of his own his flagship Africa.[17]

Ships involved

[edit]A list of the ships and commanders involved in the action was compiled by an unnamed Officer from HMS Lenox in a letter dated 23 November 1748 (later quoted and published in The Naval Chronicle[24]).

Britain

[edit]| Ship | Guns | Commander | Notes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tilbury | 60 | Captain Charles Powlett | [25] | |

| Strafford | 60 | Captain David Brodie | ||

| Cornwall | 80 | Rear-Admiral Charles Knowles Captain Polycarpus Taylor |

||

| Lenox | 70 | Captain Charles Holmes | ||

| Warwick | 60 | Captain Thomas Innes | ||

| Canterbury | 60 | Captain Edward Clark | ||

| Oxford | 50 | Captain Edmond Toll | Not in the line of battle |

Spain

[edit]| Ship | Guns | Commander | Notes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Invencible | 74 | Rear-Admiral Benito Spínola Captain Antonio Marroquin |

[25] | |

| Conquistador | 64 | Captain Tomás de San Justo † | Captured | |

| África | 74 | Vice-Admiral Andrés Reggio | Later scuttled | |

| Dragón | 64 | Captain Manuel de Paz | ||

| Nueva España | 64 | Captain Fernando Varela | ||

| Real Familia | 64 | Captain Marcos Forrestal | ||

| Galga | 36 | Captain Pedro de Garaycoechea | Not in the line of battle |

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Bruce p 289

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Marley pp 412-13

- ^ Clodfelter p 82

- ^ a b c Thomas p 263

- ^ a b c d e f Allen, Joseph (1852). Battles of the British Navy, Volume 1. G. Bell & Sons. pp. 167–69.

- ^ a b c d Harding p 332-33

- ^ Browning, Reed (1971). "The Duke of Newcastle and the Financing of the Seven Years' War". Journal of Economic History. 31 (2): 109–113. doi:10.1017/S0022050700090914. S2CID 154806047.

- ^ Marley p. 261

- ^ Harding, Preface

- ^ Williams (1999), p. 215.

- ^ Black, p 94

- ^ Roskill, p. 60

- ^ Rodger p. 244

- ^ a b c d . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900. p. 293

- ^ a b c d e Richmond pp 132-34

- ^ Richmond pp 135-37

- ^ a b c d e f Tunstall pp 101-03

- ^ a b Richmond pp 136-38

- ^ a b c Southworth, John Van Duyn (1968). War at Sea: The age of sails Volume 2 of War at Sea, War at Sea. Twayne Publishers. p. 178.

- ^ a b Richmond pp 140-42

- ^ a b c Clowes p 136

- ^ a b c d e Richmond pp 143-45

- ^ Thomas p 262

- ^ The Naval Chronicle, Containing a General and Biographical History of the Royal Navy of the United Kingdom, with a Variety of Original Papers on Nautical Subjects. Vol. 1. London: J. Gold. 1799. p. 114.

- ^ a b Clowes (1898), p. 135.

References

[edit]- Bruce, Anthony (1999). An Encyclopaedia of Naval History. Checkmark Books. ISBN 0-8160-4068-0.

- Clowes, William Laird (1898). The Royal Navy, a History from the Earliest Times to the Present. Vol. 3. London: Sampson Low, Marston and Company.

- Clowes, William Laird (1996). The Royal Navy: A History from the Earliest Times to 1900. Chatham Pub. ISBN 9781861760104.

- Clodfelter, Micheal (2002). Warfare and armed conflicts: a statistical reference to casualty and other figures, 1500-2000. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0786412044.

- Harding, Richard (2010). The Emergence of Britain's Global Naval Supremacy: The War of 1739-1748. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 9781843835806.

- Marley, David (2008). Wars of the Americas: A Chronology of Armed Conflict in the Western Hemisphere. ABC CLIO. ISBN 978-1598841008.

- McNeill, John Robert (1985). Atlantic empires of France and Spain: Louisbourg and Havana, 1700-1763. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807816691.

- Palmer, Michael (2005). Command at sea: naval command and control since the sixteenth century. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01681-5.

- Richmond, Theo R (2009). The Navy in the War of 1739-48. BiblioBazaar, LLC. ISBN 978-1-113-20983-2.

- Rodger, NAM (2006). Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain, 1649-1815. Penguin Books.

- Roskill, Stephen Wentworth (1957). H. M. S. Warspite: the story of a famous battleship. Collins.

- Simms, Brendan (2008). Three Victories and a Defeat: The Rise and Fall of the First British Empire. Penguin Books.

- Thomas, David (1998). Battles & Honours of Royal Navy. Pen and Sword. ISBN 9780850526233.

- Tunstall, Brian (2001). Naval warfare in the age of sail: the evolution of fighting tactics, 1650-1815. Wellfleet Press. ISBN 0-7858-1426-4.

- Williams, Glyn (1999), The Prize of All the Oceans, New York: Viking, ISBN 0-670-89197-5.